Abstract

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a constellation of neurodevelopmental disorders associated with disruptions in social, cognitive, and/or motor behaviors. ASD are more prevalent among males than females and characterized by aberrant social and language development, and a dysregulation in stress responding. Levels of progesterone (P4) and its metabolite 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (3α,5α-THP) are higher and more variable in females compared to males. 3α,5α-THP is also a neurosteroid, which can be rapidly produced de novo in the brain, independent of peripheral gland secretion, and can exert homeostatic effects to modulate stress responding. An inbred mouse strain that has demonstrated an ASD-like behavioral and neuroendocrine phenotype is BTBR T +tf/J (BTBR). BTBR mice have deficits in cognitive and social behavior and have high circulating levels of the stress hormone, corticosterone. We hypothesized that central 3α,5α-THP levels would be different among BTBR mice compared to mice on a similar background C57BL/6J (C57/J) and 129S1/SvlmJ (129S1). Tissues were collected from BTBR, C57/J and 129S1 male mice and levels of corticosterone, P4, and 3α,5α-THP in plasma and hypothalamus, midbrain, hippocampus, and cerebellum were measured by radioimmunoassay. Circulating levels of corticosterone, P4, and 3α,5α-THP were significantly higher among BTBR, than C57/J and 129S1, mice. Levels of P4 in the cerebellum were significantly higher than other brain regions among all mouse strains. Levels of 3α,5α-THP in the hypothalamus of BTBR mice were significantly higher compared to C57/J and 129S1 mice. These findings suggest that neuroendocrine dysregulation among BTBR mice extends to 3α,5α-THP.

Keywords: affect, learning, memory, stress, neurosteroid, autism spectrum disorder, allopregnanolone, corticosterone

1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) affects approximately 1 in 150 children. It is characterized by aberrant social (social interaction, communication), cognitive (perseveration), and/or motor (repetitive stereotyped behaviors) behavior [1] and dysregulation in stress-responding [2–3]. Along with difficulty tolerating novelty and environmental stressors [4], those with ASD often suffer from co-morbid neurological disorders, such as seizures [5]. Thus, ASD is a pervasive developmental disorder that is associated with dysregulation in several behaviors.

There are gender differences in the incidence and/or symptomology of ASD, such that males are four times more likely to be diagnosed compared to females. As well, boys with ASD performed better on eye-hand integration and perception skills, and have higher nonverbal IQ social quotients compared to girls. When nonverbal IQ was controlled for, gender differences on integration and perception disappeared. However, boys demonstrated more unusual visual responses and more stereotypic play compared to girls [6]. Given the prominence of gender differences in ASD incidence and/or symptomology, hormones or other neuroendocrine factors may be involved in ASD and need to be further elucidated.

Hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA) stress-responding is modified among people with ASD [7], such that circulating levels of the steroid, cortisol, are elevated [2,8]. However, behavior may be influenced by external or internal factors, such as time of day or hormonal state [9], and some studies have not reported HPA differences [10–13]. Thus, there may be neuroendocrine differences in ASD that are related to the expression and/or development of ASD.

One neuroendocrine factor that may be involved in ASD is a progesterone (P4) metabolite, 5α-pregnan-3α-ol-20-one (3α,5α-THP). Sources of 3α,5α-THP are the ovaries, adrenals, and de novo formation in the brain. 3α,5α-THP levels vary across the life span, such that females experience variable and higher levels, while males have lower and more stable levels [14]. 3α,5α-THP can feedback on HPA responding to reinstate parasympathetic tone [15–19]. Furthermore, female rodents demonstrate enhanced social, cognitive and affective behaviors when 3α,5α-THP levels are elevated [20–21]. Among male rodents, disruption in 3α,5α-THP formation can enhance aggression and decrease cognitive function [22]. As well, 3α,5α-THP administration or enhancing its formation provide neuroprotection [23–24]. Given sex differences in 3α,5αTHP and its potential effects on behaviors associated with ASD, we began to examine the role of 3α,5α-THP in an animal model of ASD. Our foray into this was restricted to male mice, to control for inherent sex differences in progestogens.

An inbred mouse strain that has demonstrated reliable decrements in social behavior and learning is BTBR T +tf/J (BTBR) mice compared to other mouse strains, including C57BL/6J (C57/J), DBA/2J, FVB/NJ, and BALB/cByJ [25–27]. BTBR mice also display repetitive behaviors, do not prefer novel appetitive reward scents, demonstrate altered fear and object memory, and show heightened stress-reαsponding and corticosteroid levels [28–31]. The BTBR phenotype is neither due to differences in basal levels of anxiety, nor motor capability [26], and is not altered by cross-fostering to C57/J mice [29], which have demonstrated normative performance in roto-rod learning and react less in the contextual and cued fear tasks [32]. In the following experiment, we investigated whether corticosterone and 3α,5α-THP levels, were different among BTBR, and C57/J and 129S1/SvImJ (129S1) mice. We hypothesized that if 3α,5α-THP has a role in ASD-like phenotype, that BTBR mice would be expected to have atypical corticosterone and/or 3α,5α-THP levels, compared to C57/J and 129S1 mice.

2. Materials and Methods

Methods were pre-approved by the IACUC at the University at Albany-SUNY and carried out using adequate measures to minimize pain or discomfort, as outlined in NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (#80-23, 1996).

2.1. Animals and Housing

Adult, age-matched (50–55 days of age) male mice from the BTBR (n=7), C57/J (n=6) and 129S1 (n=6) mouse strains were generated at the University at Albany-SUNY from stocks originally acquired from The Jackson Laboratory. All mice were group-housed, had ad libitum access to rodent chow and tap water in their home cages, and handled daily for health checks until removed from the housing room for tissue collection.

2.2. Tissue Collection and Measurement

Mice were removed directly from their respective home cages one at a time in a randomized order just before being sacrificed. Mice were sacrificed one strain at a time. The area used for sacrifice was cleaned between subjects and strains. Trunk blood was obtained following cervical dislocation and rapid decapitation. Blood was kept on ice and coagulated until centrifugation at 3,000 × g. Plasma was stored at −20°C. Whole brains were extracted, flash frozen on dry ice, within 2 min, and stored at −80°C until radioimmunoassay.

2.3. Radioimmunoassay for steroid hormones

Immediately prior to radioimmunoassay for P4, 3α,5α-THP, and corticosterone, conducted per previous methods [33–36], the hypothalamus, midbrain, hippocampus, and cerebellum were dissected out.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to examine if there were differences between C57/J, 129S1 and BTBR mouse strains in plasma hormone levels. Two way ANOVAs with strain as a between and brain region a within factor were used to examine central and P4 and 3α,5α-THP. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to determine interactions between brain region and strain on P4 and 3α,5α-THP levels. The alpha level for statistical significance was p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. BTBR, vs C57/J and 129S1, mice have higher corticosterone, P4, & 3α,5α-THP plasma levels

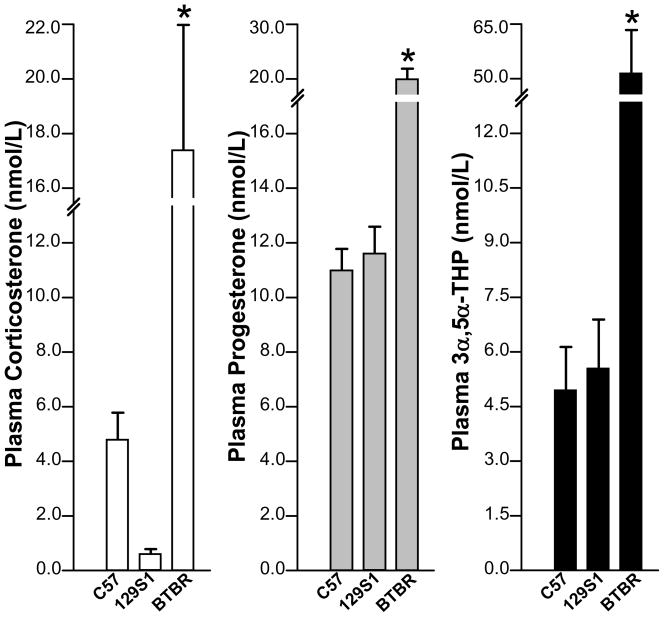

There were significant effects of strain on plasma levels of corticosterone [F(2,16)=8.92, p<0.05], P4 [F(2,16)=15.47, p<0.05] and 3α,5α-THP [F(2,16)=13.71, p<0.05]. As Figure 1 shows, BTBR mice had significantly higher levels of corticosterone P4, and 3α,5α-THP, than did C57/J and 129S1 mice.

Figure 1.

Compared to C57/J and 129S1 mice, BTBR mice had significantly higher plasma corticosterone, progesterone, and 3α,5α-THP levels. * indicates p<0.05.

3.2. BTBR mice may have higher 3α,5α-THP levels in hypothalamus compared to C57/J and 129S1 mice

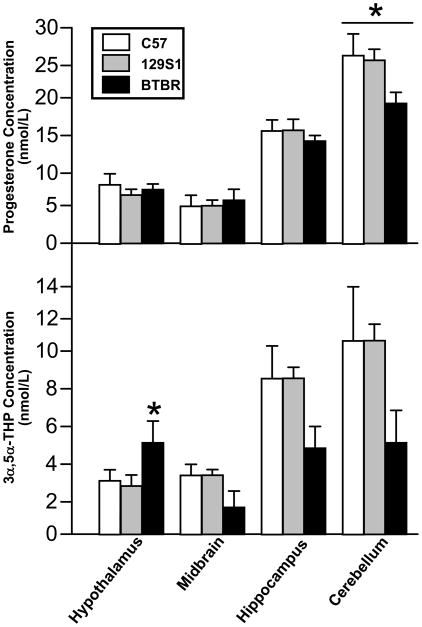

There were significant effects of brain region [F(3,48)=102.29, p<0.05], but not strain on P4 levels. Progesterone levels were greater in the cerebellum than any other brain region.

There were significant effects of brain region [F(3,48)=23.58, p<0.05], and an interaction between brain region and strain [F(6,48)=3.92, p<0.05] on 3α,5α-THP levels. 3α,5α-THP levels were significantly higher in the hypothalamus of BTBR compared to C57/J and 129S1 mice.

4. Discussion

These findings support our hypothesis that stress hormone and 3α,5α-THP levels are altered among BTBR mice, an animal model of ASD. Among C57/J and 129S1 mice, corticosterone, P4 and 3α,5α-THP levels in plasma were basal, whereas BTBR mice demonstrate a marked elevation of these steroids, comparatively. In the brain, P4 levels were higher in the cerebellum of C57/J, 129S1 and BTBR mice. However, among BTBR mice 3α,5α-THP levels are higher in hypothalamus, compared to C57/J and 129S1 mice. These data support the notion that 3α,5α-THP synthesis may be deficient among BTBR mice, which may underlie aspects of the ASD phenotype associated with this mouse strain.

The present findings confirm previous results that show BTBR mice have elevated gluccocorticoid levels. Indeed, BTBR mice have demonstrated higher baseline corticosteroid levels compared to C57/J mice, as well as enhanced anxiety responding in the elevated plus maze following tail suspension [31]. These findings confirm our results showing BTBR mice have elevated corticosterone levels compared to other mouse strains. However, possibly owing to the nature of stressors, previously reported levels were higher than ours, perhaps in part due to animals being directly taken out of their home cages without prior handling, or perhaps differences associated with stress of termination. These findings are congruent with clinical investigations that report perturbed HPA [2,3,37–38] or exacerbated cortisol [39] responses among people with ASD. Thus, BTBR mice show altered stress-responding which may be related to their expression of an ASD-like behavioral phenotype.

In addition to stress-responding, BTBR mice have demonstrated altered cerebellar, cognitive and affective behaviors. In particular, BTBR mice display repetitive behaviors, altered fear and object memory, have a low preference for social novelty, and have altered affective behavior following an acute stressor [26,28–29, 30–31]. Indeed, 3α,5α-THP can mediate each of these processes, such that when 3α,5α-THP levels are elevated, female rodents demonstrate increased sociability, cognitive performance and/or affective behaviors, as well as improved stress-responding, compared to when levels are lower [40]. We have expanded upon the BTBR phenotype by demonstrating BTBR mice have altered 3α,5α-THP levels, in addition to altered corticosterone levels, compared to other mouse strains. The behavioral tasks BTBR mice have been examined in, as well as altered stress-responding and neuroendocrine factors that have been demonstrated, provide face validity for the BTBR mouse strain as an animal model of ASD and for neuroendocrine factors to potentially play a role in ASD expression.

The potential involvement of neurosteroids in ASD has been investigated heretofore but largely with other neurosteriods. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), produced by the adrenals, has been examined in children and adolescents with ASD, but no differences were found among males compared to controls [41]. However, DHEA and DHEA-S levels were investigated in male adults with ASD, demonstrating those with ASD have lower DHEA-S levels compared to controls [42]. Low levels of DHEA-S may impact N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors [43–44], and given the role of NMDARs in the behavioral phenotype and treatment of psychiatric disorders [45,46], neurosteroids, such as DHEA-S, may impact ASD. Furthermore, the most commonly prescribed psychotropic treatment for ASD is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [47–49], although antipsychotics and antiepileptic drugs are also prescribed [50,51]. A common feature of some SSRIs, antipsychotics, and AEDs is their effects to enhance 3α,5α-THP formation [52–56]. Thus, the role of neuroendocrine factors, such as 3α,5α-THP, in ASD phenotypes need to be further elucidated to determine their role in gender differences in incidence and/or expression of ASD.

Figure 2.

C57/J, 129S1 and BTBR mice have higher progesterone levels in cerebellum compared to other brain regions. BTBR mice may have higher 3α,5α-THP levels in hypothalamus than do C57/J and 129S1 mice, resulting in an interaction between brain region and strain in 3α,5α-THP levels, but not progesterone levels. * indicates p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from NIMH (MH06769801), NSF (IBN0316083) and an intramural Faculty Research Award Program. We thank Dr. Jacqueline Crawley and Dr. Jill Silverman, Laboratory of Behavioral Neuroscience, Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Mental Health, who provided scientific input and practical assistance. We also thank the assistance of Dr. Valerie Bolivar and Dr. Derek Symula at Wadsworth Center. Tissues generated for training purposes for Dr. Symula provided the basis for this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chugani DC. Role of altered brain serotonin mechanisms in autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;2:S16–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marinović-Ćurin J, Terzić J, Bujas-Petković Z, Zekan L, Marinović-Terzić I, Susnjara IM. Lower cortisol and higher ACTH levels in individuals with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:443–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1025019030121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marinović-Ćurin J, Marinović-Terzić I, Bujas-Petković Z, Zekan L, Skrabić V, Dogaš Z, Terzić J. Slower cortisol response during ACTH stimulation test in autistic children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0632-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child. 1943;2:217–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deykin EY, MacMahon B. The incidence of seizures among children with autistic symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136:1310–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord C, Schopler E, Revicki D. Sex differences in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1982;12:317–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01538320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waterhouse L, Fein D, Modahl C. Neurofunctional mechanisms in autism. Psychol Rev. 1996;103:457–89. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.103.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tani P, Lindberg N, Matto V, Appelberg B, Nieminen-von Wendt T, von Wendt L, Porkka-Heiskanen T. Higher plasma ACTH levels in adults with Asperger syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:533–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wersinger SR, Martin LB. Optimization of laboratory conditions for the study of social behavior. ILAR J. 2009;50:64–80. doi: 10.1093/ilar.50.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen LM, Gispen-de Wied CC, Van der Gaag RJ, ten Hove F, Willemsen-Swinkels SW, Harteveld E, Van Engeland H. Unresponsiveness to psychosocial stress in a subgroup of autistic-like children, multiple complex developmental disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25:753–64. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nir I, Meir D, Zilber N, Knobler H, Hadjez J, Lerner YJ. Brief report: circadian melatonin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, prolactin, and cortisol levels in serum of young adults with autism. Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25:641–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02178193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandman CA, Barron JL, Chicz-DeMet A, DeMet EM. Brief report: plasma beta-endorphic and cortisol levels in autistic patients. J Autism Dev Disord. 1991;21:83–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02207000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tordjman S, Anderson GM, McBride PA, Hertzig ME, Snow ME, Hall LM, Thompson SM, Ferrari P, Cohen DJ. Plasma beta-endorphin, adrenocorticotropin hormone, and cortisol in autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:705–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frye CA, Walf A. Effects of progesterone administration and APPswe+PSEN1De9 mutation for cognitive performance of mid-aged mice. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2008;89:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bitran D, Foley M, Audette D, Leslie N, Frye CA. Activation of peripheral mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptors in the hippocampus stimulates allopregnanolone synthesis and produces anxiolytic-like effects in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:64–71. doi: 10.1007/s002130000471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patchev VK, Hassan AH, Holsboer DF, Almeida OF. The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone attenuates the endocrine response to stress and exerts glucocorticoid-like effects on vasopressin gene transcription in the rat hypothalamus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:533–40. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patchev VK, Shoaib M, Holsboer F, Almeida OF. The neurosteroid tetrahydroprogesterone counteracts corticotropin-releasing hormone-induced anxiety and alters the release and gene expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the rat hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 1994;62:265–71. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddy DS. The clinical potentials of endogenous neurosteroids. Drugs Today (Barc) 2002;38:465–85. doi: 10.1358/dot.2002.38.7.820115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Inhibiting progesterone metabolism in the hippocampus of rats in behavioral estrus decreases anxiolytic behaviors and enhances exploratory and antinociceptive behaviors. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2001;1:287–96. doi: 10.3758/cabn.1.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frye CA, Rhodes ME, Petralia SM, Walf AA, Sumida K, Edinger KL. 3alpha-hydroxy-5alpha-pregnan-20-one in the midbrain ventral tegmental area mediates social, sexual, and affective behaviors. Neuroscience. 2006a;138:1007–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walf AA, Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Ovarian steroids enhance object recognition in naturally cycling and ovariectomized, hormone-primed rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2006;86:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agís-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Pibiri F, Kadriu B, Costa E, Guidotti A. Down-regulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis in corticolimbic circuits mediates social isolation-induced behavior in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709419104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman AF, Riegel AC, Lupica CR. Functional localization of cannabinoid receptors and endogenous cannabinoid production in distinct neuron populations of the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:524–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes ME, McCormick CM, Frye CA. 3alpha,5alpha-THP mediates progestogens’ effects to protect against adrenalectomy-induced cell death in the dentate gyrus of female and male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;78:505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolivar VJ, Walters SR, Phoenix JL. Assessing autism-like behavior in mice: Variations in social interactions among inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, Barbaro JR, Wilson LM, Threadgill DW, Lauder JM, Magnuson TR, Crawley JN. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McFarlane HG, Kusek GK, Yang M, Phoenix JL, Bolivar VJ, Crawley JN. Autism-like behavioral phenotypes in BTBR T+tf/J mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:152–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Poe MD, Nonneman RJ, Young NB, Koller BH, Crawley JN, Duncan GE, Bodfish JW. Development of a mouse test for repetitive, restricted behaviors: relevance to autism. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188:178–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang M, Zhodzishsky V, Crawley JN. Social deficits in BTBR T+tf/J mice are unchanged by crossfostering with C57BL/6J mothers. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25:515–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacPherson P, McGaffigan R, Wahlsten D, Nguyen PV. Impaired fear memory, altered object memory and modified hippocampal synaptic plasticity in split-brain mice. Brain Res. 2008;1210:179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benno R, Smirnova V, Vera S, Liggett A, Schanz N. Exaggerated responses to stress in the BTBR T+tf/J mouse: an unusual behavioral phenotype. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197:462–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bothe GW, Bolivar VJ, Vedder MJ, Geistfeld JG. Genetic and behavioral differences among five inbred mouse strains commonly used in the productions of transgenic and knockout mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:149–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183x.2004.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frye CA, McCormick CM, Coopersmith C, Erskine MS. Effects of paced and non-paced mating stimulation on plasma progesterone, 3 alpha-diol and corticosterone. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:431–9. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frye CA, Bayon LE. Mating stimuli influence endogenous variations in the neurosteroids 3alpha,5alpha-THP and 3alpha-Diol. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:839–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frye CA, Vongher JM. 3α,5α-THP in the midbrain ventral tegmental area of rats and hamsters is increased in exogenous hormone states associated with estrous cyclicity and sexual receptivity. J Endocrinol Invest. 1999;22:455–464. doi: 10.1007/BF03343590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frye CA, Rhodes ME, Raol YH, Brooks-Kayal AR. Early postnatal stimulation alters pregnane neurosteroids in the hippocampus. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006b;186:343–50. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0253-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richdale AL, Prior MR. Urinary cortisol circadian rhythm in a group of high-functioning children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1992;22:433–47. doi: 10.1007/BF01048245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamazaki K, Saito Y, Okada F, Fujieda T, Yamashita I. An application of neuroendocrinological studies in autistic children and Heller’s syndrome. J Autism Child Schizophr. 1975;5:323–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01540679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corbett BA, Mendoza S, Abdullah M, Wegelin JA, Levine S. Cortisol circadian rhythms and response to stress in children with autism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frye CA. Progestogens influence motivation, reward, conditioning, stress, and/or response to drugs of abuse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:209–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tordjman S, Anderson GM, McBride PA, Hertzig ME, Snow ME, Hall LM, Ferrari P, Cohen DJ. Plasma androgens in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25:295–304. doi: 10.1007/BF02179290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strous RD, Maayan R, Lapidus R, Stryjer R, Lustig M, Kotler M, Weizman A. Dehydroepiandrosterone augmentation in the management of negative, depressive, and anxiety symptoms in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:133–41. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergeron R, de Montigny C, Debonnel G. Potentiation of neuronal NMDA response induced by dehydroepiandrosterone and its suppression by progesterone: effects mediated via sigma receptors. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1193–202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01193.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monnet FP, Mahé V, Robel P, Baulieu EE. Neurosteroids, via sigma receptors, modulate the [3H]norepinephrine release evoked by N-methyl-D aspartate in the rat hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3774–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Javitt DC, Zukin SR. Recent advances in the hencyclidine model of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:1301–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coyle JT. The glutamatergic dysfunction hypothesis for schizophrenia. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1996;3:241–53. doi: 10.3109/10673229609017192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langworthy-Lam KS, Aman MG, Van Bourgondien ME. Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines in individuals with autism in the Autism Society of North Carolina. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:311–22. doi: 10.1089/104454602762599853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aman MG, Arnold LE, Armstrong SC. Review of serotonergic agents and perseverative behavior in patients with developmental disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1999;5:279–89. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aman MG, Lam KSL, Collier-Crespin A. Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines among individuals with autism in the Autism Society of Ohio. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:527–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1025883612879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson GM, Hoshino Y. Neurochemical studies of autism. In: Cohen DJ, Volkmar FR, editors. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. Vol. 2. New York: Wille; 1999. pp. 325–343. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young JG, Kavanagh ME, Anderson GM, Shaywitz BA, Cohen DJ. Clinical neurochemistry of autism and associated disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 1982;12:147–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01531305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frye CA, Seliga AM. Olanzapine and progesterone have dose-dependent and additive effects to enhance lordosis and progestogen concentrations of rats. Physiol Behav. 2002;76:151–8. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frye CA, Seliga AM. Olanzapine’s effects to reduce fear and anxiety and enhance social interactions coincide with increased progestogen concentrations of ovariectomized rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:657–73. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khisti RT, Chopde CT, Jain SP. Antidepressant-like effect of the neurosteroid 3alpha-hydroxy-5alphapregnan-20-one in mice forced swim test. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ströhle A, Romeo E, Hermann B, Pasini A, Spalletta G, di Michele F, Holsboer F, Rupprecht R. Concentrations of 3 alpha-reduced neuroactive steroids and their precursors in plasma of patients with major depression and after clinical recovery. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:274–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00328-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uzunova V, Sheline Y, Davis JM, Rasmusson A, Uzunov DP, Costa E, Guidotti A. Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]