Abstract

Objective

Depression worsens outcomes of physical illness. However, it is unknown whether this negative effect persists after depressive symptoms remit in older adults. This study examined whether prior depression history predicts deterioration of physical health in community-dwelling older adults.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

Three urban communities in the United States

Participants

351 adults aged 60 or older – 145 with a history of major or non-major depression in full remission and 206 concurrent age- and gender-matched comparison subjects with no history of mental illness.

Measurements

Participants were assessed at baseline, 6 weeks, 1 year and 2 years for physical health functioning (the Physical Component Summary of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey) and chronic medical burden (the Chronic Disease Score). Given the repeated nature of measurements, linear mixed model regression was performed.

Results

Both physical functioning and chronic medical burden deteriorated more rapidly over time in the group with prior depression history compared to comparison subjects, and these changes were independent of the measures of mental health functioning, depressive symptoms and sleep quality. Similar results were observed when those who developed depressive episodes during follow-up were excluded.

Conclusion

A prior history of clinical depression is associated with a faster deterioration of physical health in community-dwelling older adults, which is not explained by current levels of depressive symptoms and mental health functioning, nor by recurrence of depressive episodes. Careful screening for a past history of depression may identify those older adults at greatest risk for physical declines and chronic medical burden.

Keywords: prior depression history, physical health, older adults

Introduction

Depressive conditions, including major and non-major depressive disorders, in older adults are relatively common1 and have been consistently linked to disability and physical declines.2,3 Whereas it is generally thought that effective treatment of depression improves depressive symptoms and functional outcomes,4,5 sometimes even to normal levels,6,7 studies in younger adults have reported that prior history of depression increased the likelihood of poor health,8,9 metabolic syndrome,10 cardiovascular disease,11-14 diabetes,15 and in-hospital mortality.16 Hence, it has been hypothesized that the negative effect of depression on physical health may persist even after the depressive episode remits in younger adults.

The relationships between prior history of depression and changes in physical health in older adults have not been previously examined. Moreover, conclusions from previous studies in younger adults are limited by several issues: subjects with current depression were not excluded;10-13,15-17 study design was not truly prospective as prior depression history and health outcomes were assessed concurrently;9,12,14,15,17 health outcomes were measured at a single time point making the evaluation of progression of medical burden impossible;8,9,12-17 the role of mental health functioning or current depressive symptoms in the prediction of health outcomes was not taken into account;8,10,11,13,15 and only women were studied.9,10,12,14,17

To address these limitations, this two-year community-based longitudinal study of older adults examined the prospective relationship between prior history of depression and physical health as measured by self-reported physical functioning and objectively assessed chronic medical burden. The measures of physical functioning and chronic medical burden consisted, respectively, of the Physical Component Summary of the 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey, a widely used questionnaire of the health-related quality of life,18 and the Chronic Disease Score, a measure based on use of prescription medications, which has been shown to predict hospitalization risk and mortality.19 We hypothesized that prior depressive episodes would predict a deterioration of physical health, even after a period of maintained full remission, and that this association would be independent of concurrent measures of mental health status. To test this hypothesis, repeated measurements of health status were obtained in a sample of community-dwelling older adults. We compared measures of physical functioning and chronic medical burden in those with a prior lifetime history of depression in full remission with similar measurements in a concurrently assessed age and gender-matched comparison group with no history of mental illness. The prospective analyses took into account mental health functioning, subclinical depressive symptoms, sleep quality, and development of depressive episodes during follow-up.

Methods

Overview

The Depression Substudy of the Veterans Affairs Cooperatives Trial #403, Shingles Prevention Study (SPS), provided the data presented in this paper. The SPS was a randomized multicenter efficacy trial of an investigational varicella-zoster virus vaccine against herpes zoster (shingles) in community-dwelling adults aged 60 years and older.20 Based on the results from a depression screening, subjects were enrolled in the Depression Substudy, a prospective cohort study conducted between July 2001 and June 2006. The study involved psychiatric interviews and assessment of depressive symptom severity, sleep quality, chronic medical illness and health functioning at baseline and three follow-up visits over two years as previously described.21,22 The institutional review boards of the University of Colorado, University of California at San Diego and University of California at Los Angeles approved all procedures.

Subjects & Procedure

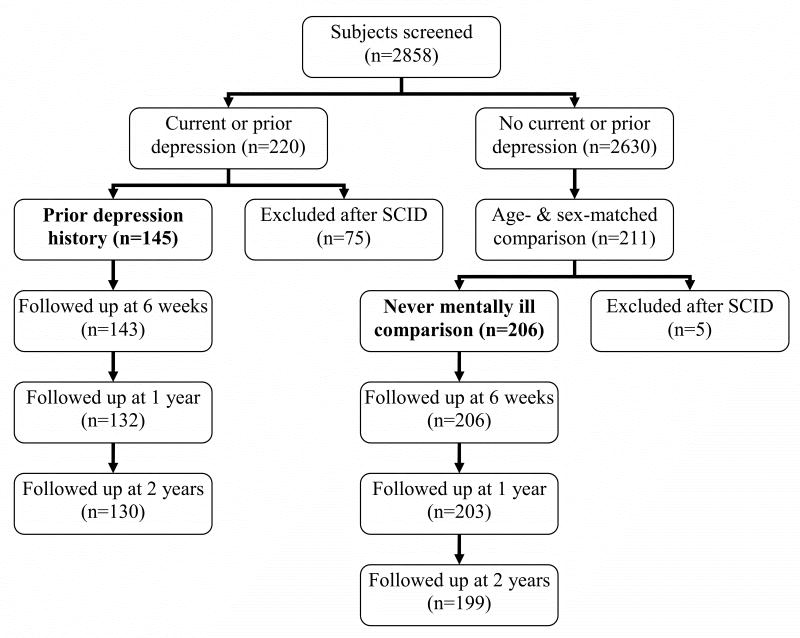

Community-dwelling older adults were recruited from three urban communities (Denver, Colorado, and Los Angeles and San Diego, California) as previously described.21 A total of 2858 subjects entering the SPS underwent screening for entry into the Depression Substudy (Figure 1). Depression screening included completion of an abbreviated version of the Centers for Epidemiological Study of Depression Scale (CES-D)23 and answering two questions about prior episodes of depression or prior treatment for depression. Persons who scored above the previously validated CES-D cutoff for depression or answered affirmatively for having had depression or received treatment for depression were initially selected for a further interview (n=220). In addition, a sample of gender- and age- matched (within ±5 years) participants who were being enrolled concurrently in the SPS and did not meet depression screening criteria were selected as comparison subjects (i.e., never been mentally ill, n=211).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study

At baseline, all initially selected subjects underwent a psychiatric diagnostic interview that included administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (SCID),24 with characterization of the most recent three episodes (e.g., major vs. non-major depression, psychotropic medication used, date of remission). Depression severity was assessed using the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D).25 The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), a 19-item self-report measuring problematic sleep, was used to assess perceived sleep quality.26

The Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) was employed to measure health functioning.27 The SF-36 is a 36-item questionnaire which yields an eight-scale profile of scores (Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Role-Emotional and Mental Health) as well as physical and mental health summary measures. The eight scales are hypothesized to form two distinct higher ordered clusters in factor analysis according to the physical and mental health variance that they have in common.28 Three scales (Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain) correlate most highly with the physical factor and contribute most to the scoring of the Physical Component Summary (PCS) measure. The mental factor correlates most highly with the Mental Health and Role-Emotional scales, which also contribute most to the scoring of the Mental Component Summary (MCS) measure. Three of the scales (Vitality, General Health, and Social Functioning) correlate with both factors.

The Chronic Disease Score (CDS) was administered as an interview by a nurse coordinator, and provided an objective measure of chronic medical burden as its score is based on selected prescription medications used over a six-month period.19 Participants were instructed to bring their medication bottles and prescriptions to the study appointment, and the nurse coordinator recorded all medications used over the last six months. Because the CDS does not include psychotropic or analgesic medications, this measure provides an estimate of global chronic disease status independent of psychiatric and pain-related symptoms. Hence, the CDS is less influenced by psychological distress than self-rated health status measures such as SF-36. Scores can range from 0 to 35; scores above seven are associated with a five times greater hospitalization risk and 10 times greater risk of dying within one year compared to a score of zero.19

Of the 220 older adults who screened positive for depression or prior depression history and underwent SCID interview, 68 were excluded due to current depressive disorders, 4 due to alcohol/substance abuse-related depression, and 3 due to breathing-related sleep disorder. Older adults with current depression were excluded because this study focused on the impact of prior rather than current depression on health functioning. The remaining 145 subjects reported a prior depression history (either major or non-major depressive disorder); none fulfilled diagnostic criteria for a current depressive disorder (neither major nor non-major) or for any other current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) disorder (including anxiety and substance dependence disorders). Of these 145 subjects with a prior depression, 111 met criteria for history of major depression and 34 met criteria for history of non-major depression (1 for dysthymia and 33 for depression not otherwise, e.g. minor depressive disorder). Non-major or sub-threshold depression was assessed along with major depression as many elderly persons do not meet diagnostic criteria for major depression, yet non-major depressive conditions are associated with cumulative disability similar to major depression.29

Of the 211 subjects who did not reach screening criteria for a current depressive disorder or prior depression history and also underwent the SCID interview, 4 subjects were excluded due to past history of an Axis I disorder (e.g., alcohol dependence) and 1 due to breathing-related sleep disorder. The remaining subjects, who comprised the comparison group (n=206) represented a sample of older adults who had never been mentally ill were concurrently assessed along with the prior depression history group. The final sample at baseline (n=351), therefore, consisted of the following two groups: prior depression history (n=145) and control (never mentally ill, n=206).

Follow-up assessments were conducted at 6 weeks, 1 year and 2 years from baseline. At each follow-up visit, subjects underwent the SCID with ascertainment of major- and non-major depressive disorders. The HAM-D, PSQI, SF-36 and CDS were also repeated. There were high response rates irrespective of group status over the two year follow-up. Of 351 subjects included at baseline, 349 (99.4%), 335 (95.4%) and 329 (93.7%) were assessed respectively at 6 weeks, 1 year and 2 years. The reasons for non-participation could not always be elicited, although the most commonly mentioned reasons included refusal, not being located, and death.

PCS/MCS Scoring

The two summary measures of the SF-36, used as the outcomes instead of the eight individual scales, were computed following the published guideline.27 Eight individual scales were standardized using a z-score transformation. Each z-score was calculated by subtracting the US general population mean from each respondent's scale score and dividing the difference by the corresponding scale's standard deviation (SD) of the US general population. Then, z-scores were multiplied by the subscale factor score coefficients of the US general population for PCS and MCS. Finally, t-scores were calculated by multiplying the obtained scores by 10 and adding 50 to the product, to yield a mean of 50 and an SD of 10 for the US norm population. Hence, PCS and MCS scores lower than 50 imply a functioning below the average level observed in the US general population, aged 18-74 years.

Statistical Analysis

Stata Version 10.0 was employed for all statistical analyses and the significance level was set at P≤0.05. Given the longitudinal and repeated nature of measurement, in order to assess the temporal change of the participants' physical health according to their group status (prior depression vs. comparison), linear regression analysis using mixed effects model was implemented.30 Mixed effects regression models use all available data during follow up, can properly account for correlation between repeated measurements on the same subject, have greater flexibility to model time effects, and can handle missing data more appropriately than traditional models such as repeated-measures analysis of variance.30 We examined the impact of group status on the course of physical health measured by the PCS and the CDS. The initial regression model included the PCS – a subjective measure of physical health – as the dependent variable and group, time, and group-by-time interaction term as the independent variables. The final regression model also included the covariates considered as sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status and education) or a priori predictors of physical health functioning (mental health functioning [MCS], depressive symptoms [HAM-D] and sleep quality [PSQI]). Note that the latter group of variables were included in the analysis in their longitudinal format, i.e. they reflected all the measurements performed during the study, in order to take into account not only the baseline measures but also the evolution of these variables. The regression coefficient (B) for ‘group’ reflects the cross sectional impact of group status on physical health functioning averaged across all time points. The regression coefficient for ‘time’ reflects the temporal change in physical health functioning. The regression coefficient for ‘group-by-time interaction’ reflects the impact of group status on the course of physical health functioning and is of our main interest. We conducted the same analyses substituting the CDS – an objective measure of physical health – for the PCS. In order to remove the influence of depression outcome on physical health, all the analyses were repeated excluding those who developed SCID-ascertained depressive episodes during follow-up.

Finally, we tested the possibility of reverse causality between physical health and depression. Although depression typically worsens physical health as briefly reviewed in the introduction, the relationship between depression and physical health is likely to be bidirectional, and poor physical health can be a risk factor for late-life depression.3 Thus, we examined the impact of poor physical health at baseline on the change of depressive symptoms and the onset of depressive episodes during follow-up by conducting mixed effects linear regression and mixed effects logistic regression, respectively. Poor physical health was defined as PCS lower than 50.

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the study participants. The groups did not differ in the composition of gender, ethnicity, and veteran status. However, compared to the comparison group, the group with prior history of depression had younger mean age, more years of education and a lesser proportion of married individuals. Physical health functioning (PCS), as measured by the SF-36, did not significantly differ between the two groups, but mental health functioning (MCS) was significantly worse in the prior depression group. Both groups presented lower PCS but somewhat higher MCS in comparison to the US general population, aged 18-74 years, and this appears to be a consistent finding in older adults.31,32 Chronic medical burden as measured by CDS (an objective measure of physical health) was not significantly different between the two groups, but depressive symptom severity assessed using HAM-D (a clinician rated measure of mental health) was significantly higher in the prior depression group. Although PCS and CDS, the measures of physical health, were not significantly different when compared by simple t-tests, they were significantly worse in the prior depression group when the comparison was adjusted for age and education using multivariable linear regression (see footnote of Table 1). As to the characteristics of prior depressive episodes, the median time since last depressive episode was nearly 10 years, indicating a period of sustained full remission for most in the prior depression group. In addition, the median duration of last depressive episode was 9 months, with on average only one lifetime episode of a major depressive disorder. Nearly one-third of the prior depression group was using antidepressant medications at baseline.

TABLE 1. Baseline Characteristics of Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Prior Depression History and Comparison Subjects With No History of Mental Illness.

| Characteristics | Prior Depression (N = 145) |

Comparison (N = 206) |

t or χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (60-95 years), mean (SD) | 67.8 (6.4) | 70.0 (6.3) | 3.23 | 349 | 0.001 |

| Female, number (%) | 86 (59.3) | 105 (51.0) | 2.39 | 1 | 0.12 |

| Married, number (%) | 81 (55.9) | 139 (67.5) | 4.91 | 1 | 0.03 |

| Euro-American, number (%) | 143 (98.6) | 199 (96.6) | 1.39 | 1 | 0.24 |

| Education (10-18 years), mean (SD) | 16.0 (2.2) | 15.3 (2.3) | −2.64 | 349 | 0.009 |

| Veteran, number (%) | 50 (34.5) | 81 (39.5) | 0.92 | 1 | 0.34 |

| Physical Component Summary (14.7-61.5), mean (SD) | 47.2 (8.5) | 48.9 (8.3) | 1.77 | 349 | 0.08a |

| Mental component summary (30.0-69.8), mean (SD) | 54.0 (7.3) | 58.6 (4.6) | 7.17 | 349 | <0.001 |

| Chronic Disease Score (0-11), mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.2) | 1.9 (2.2) | −1.66 | 349 | 0.10a |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (0-16), mean (SD) | 3.1 (3.5) | 1.0 (1.7) | −7.25 | 349 | <0.001 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (0-16), mean (SD) | 5.9 (3.7) | 3.6 (2.8) | −6.58 | 349 | <0.001 |

| Time since full remission (1-674 months), median (IQR) | 118 (45–308) | — | — | — | — |

| Duration of last depressive episode (1-564 months), median (IQR) | 9 (4–18) | — | — | — | — |

| Number of prior major depressive episodes (0-5), mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.9) | — | — | — | — |

| Current use of antidepressant, number (%) | 47 (32.4) | — | — | — | — |

Notes: SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range.

When adjusted for age and education using multivariable linear regression, Physical Component Summary and Chronic Disease Score were significantly worse in the prior depression group compared with the comparison group (B = −2.34, SE = 0.91, t = −2.56, p = 0.01 and B = 0.50, SE = 0.24, t = 2.05, p = 0.04, respectively).

During the follow-up, only one comparison subject developed a depressive disorder. In contrast, among the prior depression group, the cumulative incidence of depressive disorders was 4.9% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.0% to 9.8%) at 6 weeks; 12.6% (95% CI=7.5% to 19.4%) at 1 year; and 16.9% (95% CI=11.0% to 24.3%) at 2 years. Notably, 54.2% of the participants who developed a depressive disorder during the follow-up had at least one episode of non-major or sub-threshold depression.

Impact of Group Status on the Change of Physical Health measured by PCS and CDS

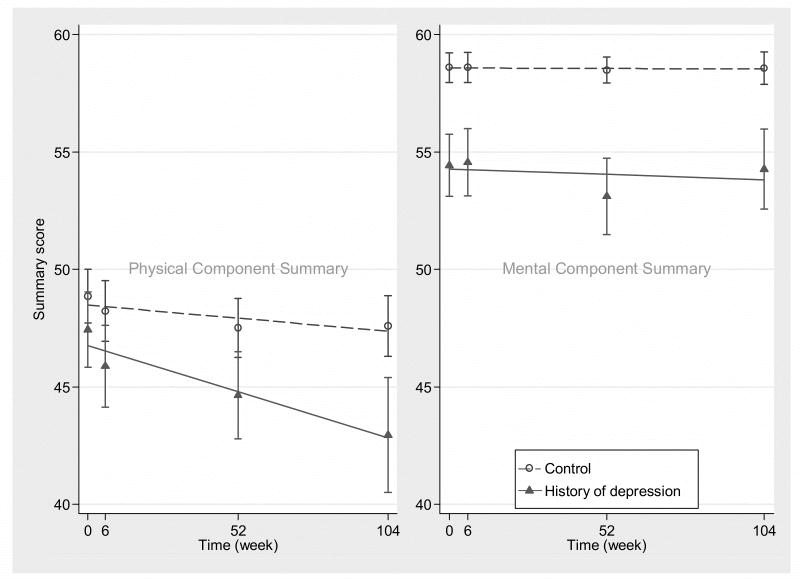

Figure 2 describes the change of physical and mental health functioning over 2 years in each group. The mean PCS dropped more than 4 points in the prior depression group over the 2 years while it was essentially unchanged in those without a depression history (unadjusted B for group-by-time interaction= -0.02, SE=0.008, Z= -2.60, P=0.01). In contrast, the mean MCS remained practically unchanged in both groups throughout the study period (B= -0.004, SE=0.006, Z= -0.63, P=0.53). The individual scales followed this pattern. Scales related to the PCS declined more rapidly in the prior depression group (Physical Functioning, B= -0.02, SE=0.01, Z= -1.89, P=0.06; Role-Physical, B= -0.08, SE=0.03, Z= -2.57, P=0.01; Bodily Pain, B= -0.04, SE= 0.02, Z= -1.85, P=0.07) as compared to those without a depression history. Scales related to the MCS remained unchanged (Mental Health, B= -0.01, SE= 0.01, Z= -1.40, P=0.17; Role-Emotional, B=0.002, SE=0.03, Z=0.09, P=0.93), whereas scales related to both the PCS and MCS presented mixed results (Vitality, B= -0.02, SE=0.01, Z= -1.32, P=0.19; General Health, B= -0.0001, SE=0.01, Z= -0.01, P=0.99; Social Functioning, B= -0.05, SE=0.02, Z= -2.82, P=0.005).

Figure 2.

Change of SF-36 summary measures (Physical Component Summary and Mental Component Summary) over time in community-dwelling older adults with prior depression history and comparison subjects with no history of mental illness

Notes: Circles and triangles represent mean scores at each time point with vertical error bars corresponding to 95% confidence intervals of mean scores. Dashed and solid lines represent linear prediction based on the mean scores over time.

For PCS, unadjusted mixed model regression analysis revealed a group effect (B= -1.88, SE=0.92, Z= -2.05, P=0.05), time effect (B= -0.01, SE=0.005, Z= -2.60, P=0.003), and group-by-time interaction (B= -0.02, SE=0.008, Z= -2.60, P=0.01). After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and MCS, HAM-D and PSQI, the results remained significant (Table 2). The significant group-by-time interaction indicated a longitudinal decline of physical health functioning, which was more rapid over time in the prior depression group compared to the comparison group. When the multivariable analysis was repeated excluding those who developed depressive episodes during follow-up, significant group-by-time interaction was again found (B= -0.02, SE=0.007, Z= -2.61, P=0.01). As nearly one-third of the participants with prior depression were using antidepressants at baseline, we repeated the multivariable analysis excluding these participants. There was a significant group-by-time interaction in this case as well (B= -0.03, SE=0.008, Z= -3.36, P=0.001), indicating antidepressant use cannot explain the observed effect.

Table 2. Effect of group (control = 0 vs. prior depression = 1), time (weeks) and group-by-time interaction on physical health functioning and chronic medical burden of community-dwelling older adults with prior depression history and comparison subjects with no history of mental illness.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Adjusted B* | SE of B | Z | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Component Summary | Group | -1.99 | 0.86 | -2.31 | 0.03 |

| Time | -0.01 | 0.004 | -2.04 | 0.05 | |

| Group × Time | -0.02 | 0.007 | -2.89 | 0.004 | |

| Chronic Disease Score | Group | 0.56 | 0.25 | 2.21 | 0.03 |

| Time | 0.004 | 0.001 | 4.66 | <0.001 | |

| Group × Time | 0.003 | 0.001 | 2.54 | 0.02 | |

B = regression coefficient; SE = standard error

Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education, mental health functioning, depressive symptoms and sleep quality

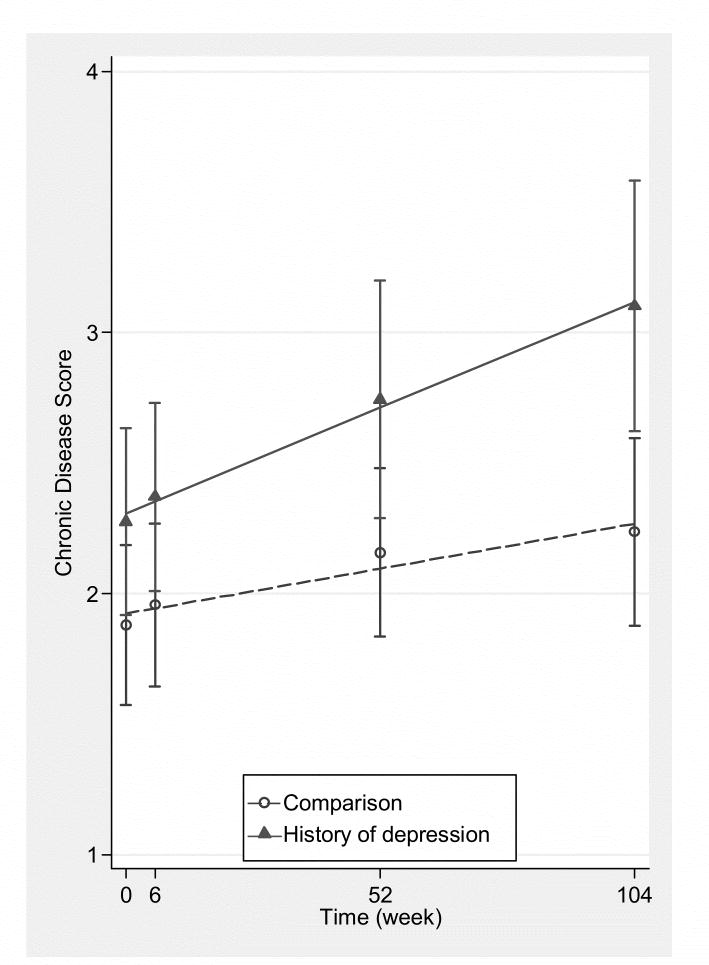

Figure 3 describes the change in chronic medical burden (CDS) in the two groups; CDS worsened at a greater rate in those with prior depression as compared to comparison subjects. Unadjusted mixed model regression analysis for CDS showed a time effect (B= 0.004, SE=0.001, Z=4.96, P<0.001) and a group-by-time interaction (B= 0.003, SE=0.001, Z= 2.67, P=0.008), but no group effect (B= 0.38, SE= 0.25, Z=1.57, P=0.12). After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and MCS, HAM-D and PSQI, the results remained significant (Table 2). The significant group-by-time interaction indicated a longitudinal increase of chronic medical burden, which was more rapid in the prior depression group compared to the comparison group. As above, when the multivariable analysis was repeated excluding those who developed depressive episodes during follow-up, a significant group-by-time interaction was still found (B= 0.004, SE=0.001, Z=2.75, P=0.006). Moreover, when the multivariable analysis was repeated without those using antidepressants at baseline, a significant group-by-time interaction was also observed (B= 0.005, SE=0.002, Z=3.03, P=0.003). Finally, there was a significant correlation between PCS and CDS, as assessed in their longitudinal format, which reflects all the measurements performed during the study (r= -0.27, df=349, P<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Change of chronic medical burden (Chronic Disease Score) over time in community-dwelling older adults with prior depression history and comparison subjects with no history of mental illness

Notes: Circles and triangles represent mean scores at each time point with vertical error bars corresponding to 95% confidence intervals of mean scores. Dashed and solid lines represent linear prediction based on the mean scores over time.

Reverse Causality: Impact of Poor Physical Health on Depression

First, according to mixed effect linear regression analyses, there was no significant impact of baseline physical health status (poor vs. good, i.e. PCS<50 vs. PCS≥50) on the change of depressive symptoms measured by HAM-D during follow-up (unadjusted B for group-by-time interaction= 0.0005, SE=0.003, Z=0.20, P=0.85). Multivariable adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and sleep quality further attenuated this association (adjusted B for group-by-time interaction= 0.0002, SE=0.003, Z=0.09, P=0.93). Second, although unadjusted mixed effect logistic regression analysis revealed poor physical health to be a significant risk factor for subsequent depressive episodes (unadjusted odds ratio 5.18, 95% CI 1.17 to 22.95, Z=2.16, P=0.04), this association was no longer significant after multivariable adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and sleep quality (adjusted odds ratio 2.78, 95% CI 0.73 to 10.63, Z=1.49, P=0.14).

Discussion

This prospective study demonstrates that a lifetime history of depression, whether major or non-major, is associated with adverse effects on physical health of older adults, even after a long period of remission. Both subjectively and objectively measured physical health deteriorated more rapidly in older adults with a prior depression history compared to those without a prior history of mental illness. Notably, these changes were independent of the current levels of depressive symptoms, sleep impairment and mental health functioning, the recurrence of depressive episodes, and the concomitant use of antidepressants. Furthermore, this faster deterioration occurred despite the relatively benign nature of the prior depressive episode. Contrary to the generally held idea that remission of depressive symptoms is associated with a reduced risk of adverse outcomes, we found that the negative effects of depression endured far beyond its resolution and correlated with prospective deterioration of health status in our study of older adults. The literature on the SF-36 health survey in a variety of disease states has suggested a minimal clinically meaningful difference to be 3 to 5 points in PCS as they reflect a magnitude of change perceptible to patients; hence the change in mean PCS score observed in the present sample (> 4) can be viewed as a clinically meaningful deterioration in physical health functioning.33,34

We were unable to identify any previous reports of an association between a prior depression history and physical health outcomes in older adults. In addition to its novelty, the present study has unique methodological features such as the recruitment of community-dwelling subjects, the inclusion of fully remitted subjects only, the consideration of both major and non-major depression histories, the longitudinal and repeated measurement of outcomes, the use of both subjective and objective health outcome measures, and the adjustment for the confounding effect of current mental health status and depressive symptoms.

The following limitations should be considered. First, because the present study was a substudy of the SPS vaccine trial, the study sample had low levels of medical morbidity, and hence, not entirely representative of the community-dwelling elderly population. Moreover, as the sample was primarily white and included veterans and their family members, the findings may not be widely generalizable to the US elderly population. Second, change in CDS could be partly reflecting differences in the use of health care services between the prior depression and comparison groups. However, this possibility is unlikely as the CDS does not include psychotropic or analgesic drugs, and there were no baseline differences of the CDS between the two groups. Third, the assessment of prior depressive episodes depended on the recollection of participants through the SCID interview. However, this method remains the gold standard for ascertainment of depression and was reported to be reliable in assessing depression history.35 Furthermore, had there been any misclassification regarding the group status (prior depression history vs. comparison), the consequence should have been an underestimated difference in the deterioration of physical health as any misclassification might have made the two groups more similar. Thus, the validity of our conclusion might not be affected by such a misclassification.

Based on the theoretical explanations for the link between current depression and decline of health status,2,3 both physiological and psychological mechanisms could explain the findings of the present study. First, although most of the physiological alterations observed during a depressed state may revert with remission of depressive symptoms, some alterations may persist and accumulate even after the depression resolves. Indeed, the presence of subclinical abnormalities such as carotid atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction has been associated with prior history of major depression in middle-aged women;12,14 and exaggerated activation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous system responses have been implicated as a pathway that underlies this association. Likewise, lifetime occurrence of depression is thought to increase ‘allostatic load’,36 which is viewed as a cumulative measure of physiologic dysregulation across multiple system with impacts on future health risks.37 Second, the state of depression is often associated with changes in a number of healthy lifestyle behaviors including diet, exercise, and sleep, which may persist after the depression remits with impacts on health.3 Similarly, given the reciprocal relationship between late-life depression and executive dysfunction – impairment in cognitive domains such as planning, organizing, sequencing, and initiation/perseveration –, it is possible that this dysfunction persists and compromises self-care and health of older adults.38 Third, prior depression history could be a risk marker of a more distal determinant of physical health outcome such as childhood maltreatment, given that the latter strongly predicts poor psychiatric and physical health outcomes in adulthood.39 Finally, although the relationship between depression and physical health is likely to be bidirectional, our study supports the notion of depression leading to physical health decline rather than the inverse directionality in community-dwelling older adults. While poor physical health did not predict depressive outcomes in our sample, the negative effects of depression on physical health endured far beyond its resolution. Two recent studies concur with our findings in that depression predicted physiological outcomes directly involved with many physical illnesses – metabolic syndrome and systemic inflammation – rather than the other way around.10,40

In conclusion, older adults who have had a prior depression show a faster rate of deterioration in physical health as measured by functional status and chronic medical burden in comparison to older adults who have no such lifetime history of a depression. These findings underscore the need for careful screening for current and past depression in primary and specialty medical care settings. Moreover, physicians treating older adults should bear in mind that a prior depression history may be a risk marker for physical health decline even when there has been a sustained full remission of depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy Lang, R.N. and Anne Lucko, R.N. for assisting the recruitment and diagnostic assessment of participants and the staff of the UCLA ATS Statistical Consulting group for providing statistical advice. This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging (R01-AG 18367) and from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH55253), and Cooperative Studies Program, Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: This paper was presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Psychosomatic Society; Baltimore, MD, March 12-15, 2008.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, van Tilburg T, et al. Major and minor depression in later life: a study of prevalence and risk factors. J Affect Disord. 1995;36:65–75. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruce ML. Depression and disability in late life: directions for future research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:102–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, et al. Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental, and social functioning. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1113–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of Disseminating Quality Improvement Programs for Depression in Managed Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agosti V, Stewart JW, Quitkin FM, et al. How symptomatic do depressed patients remain after benefiting from medication treatment? Compr Psychiatry. 1993;34:182–186. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(93)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agosti V, Stewart JW. Social functioning and residual symptomatology among outpatients who responded to treatment and recovered from major depression. J Affect Disord. 1998;47:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Weel-Baumgarten EM, van den Bosch WJ, van den Hoogen HJ, et al. The long-term perspective: a study of psychopathology and health status of patients with a history of depression more than 15 years after the first episode. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Wei HL, et al. History of depression and women's current health and functioning during midlife. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldbacher EM, Bromberger J, Matthews KA. Lifetime history of major depression predicts the development of the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged women. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:266–272. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318197a4d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen HW, Madhavan S, Alderman MH. History of treatment for depression: risk factor for myocardial infarction in hypertensive patients. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:203–209. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones DJ, Bromberger JT, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Lifetime history of depression and carotid atherosclerosis in middle-aged women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:153–160. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rumsfeld JS, Magid DJ, Plomondon ME, et al. History of depression, angina, and quality of life after acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2003;145:493–499. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner JA, Tennen H, Mansoor GA, et al. History of major depressive disorder and endothelial function in postmenopausal women. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:80–86. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195868.68122.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown LC, Majumdar SR, Newman SC, et al. History of depression increases risk of type 2 diabetes in younger adults. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1063–1067. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Ammon Cavanaugh S, Furlanetto LM, Creech SD, et al. Medical illness, past depression, and present depression: a predictive triad for in-hospital mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:43–48. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cyranowski JM, Bromberger J, Youk A, et al. Lifetime depression history and sexual function in women at midlife. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33:539–548. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044738.84813.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). 1. Conceptual-framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90016-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2271–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motivala SJ, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, et al. Impairments in health functioning and sleep quality in older adults with a history of depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1184–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1543–1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin M, Artin KHH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult - Criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition, Version 2.0. New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams JB. Standardizing the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: past, present, and future. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;251 2:II6–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03035120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index - a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User's Manual. Vol. 8. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE., Jr SF-36 health survey update. Spine. 2000;25:3130–3139. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, et al. The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: prevalence and associated functional disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:647–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper JK, Kohlmann T. Factors associated with health status of older Americans. Age Ageing. 2001;30:495–501. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.6.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hopman WM, Towheed T, Anastassiades T, et al. Canadian normative data for the SF-36 health survey. CMAJ. 2000;163:265–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hays R, Woolley J. The Concept of Clinically Meaningful Difference in Health-Related Quality of Life Research: How Meaningful is it? Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;18:419. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200018050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiebe S, Matijevic S, Eliasziw M, et al. Clinically important change in quality of life in epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:116–120. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendler KS, Neale MC, Kessler RC, et al. The lifetime history of major depression in women. Reliability of diagnosis and heritability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:863–870. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820230054003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McEwen BS. Mood disorders and allostatic load. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:200–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, et al. Price of adaptation--allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2259–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cui X, Lyness JM, Tu X, et al. Does depression precede or follow executive dysfunction? Outcomes in older primary care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1221–1228. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06040690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnow BA. Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcomes, and medical utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stewart JC, Rand KL, Muldoon MF, et al. A prospective evaluation of the directionality of the depression-inflammation relationship. Brain Behav Immun. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.011. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]