Abstract

Zolpidem is a widely prescribed sleep aid with relative selectivity for GABAA receptors containing α1–3 subunits. We examined the effects of zolpidem on the inhibitory currents mediated by GABAA receptors using whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from DMV neurons in transverse brainstem slices from rat. Zolpidem prolonged the decay time of mIPSCs and of muscimol-evoked whole-cell GABAergic currents, and it occasionally enhanced the amplitude of mIPSCs. The effects were blocked by flumazenil, a benzodiazepine antagonist. Zolpidem also hyperpolarized the resting membrane potential, with a concomitant decrease in input resistance and action potential firing activity in a subset of cells. Zolpidem did not clearly alter the GABAA receptor-mediated tonic current (Itonic) under baseline conditions, but after elevating extracellular GABA concentration with nipecotic acid, a non-selective GABA transporter blocker, zolpidem consistently and significantly increased the tonic GABA current. This increase was suppressed by flumazenil and gabazine. These results suggest that α1–3 subunits are expressed in synaptic GABAA receptors on DMV neurons. The baseline tonic GABA current is likely not mediated by these same low affinity, zolpidem-sensitive GABAA receptors. However, when the extracellular GABA concentration is increased, zolpidem-sensitive extrasynaptic GABAA receptors containing α1–3 subunits contribute to the Itonic.

Keywords: Benzodiazepine, Parasympathetic, GABA receptor, IPSC, Patch-clamp

1. Introduction

Parasympathetic control of thoracic and most subdiaphragmatic viscera is accomplished by the vagal system. Sensory fibers of the vagus nerve project to nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) neurons. In turn, NTS neurons make synaptic connections with preganglionic neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) (Davis et al., 2004; Travagli et al., 1991), which also receive signals from other central nervous centers, including hypothalamus and forebrain (Rogers et al., 1996; Travagli et al., 2006). The parasympathetic preganglionic motor neurons in the DMV subsequently send efferent vagal projections to thoracic and abdominal viscera to modulate the activities of diverse organs (Travagli et al., 2006).

The GABAergic inhibition of DMV neurons arises primarily from the NTS and factors affecting the GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory inputs from the NTS to the DMV can significantly modulate gastric motility via the vagal parasympathetic efferents (Travagli et al., 2006). A number of studies have shown that there are convergent and potent GABAergic synaptic inputs to DMV cells. As elsewhere in the brain, fast inhibitory synaptic currents (i.e., IPSCs) in the DMV are mediated by GABA acting at GABAA receptors (Davis et al., 2004; Travagli et al., 1991). Previous studies in vivo indicated that GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition is critically involved in the regulation of the gastrointestinal tract and other viscera. Microinjection of bicuculline into the DMV increases gastric motor function in cats and rats, inducing an increase in intragastric pressure, gastric motility, and gastric secretion (Sivarao et al., 1998; Washabau et al., 1995), and responses to bicuculline are eliminated by vagotomy. In addition to the phasic GABAergic currents underlying IPSCs, a tonic GABAA receptor-mediated current is expressed in DMV neurons (Gao and Smith, 2010), but the pharmacology of this current has not been fully elucidated.

Benzodiazepines are sedatives with antiepileptic and sleep-inducing effects. Side effects of these drugs include hiccups, cough, nausea and vomiting, which suggest alterations in gastrointestinal reflex functions (Nordt and Clark, 1997). Benzodiazepine binding to GABAA receptors enhances GABAA receptor function (Chen et al., 2007; Perrais and Ropert, 1999). Zolpidem, a benzodiazepine analog, is a widely prescribed hypnotic agent (Barnard et al., 1998; Harrison, 2007). Zolpidem has a high affinity for GABAA receptors containing α1 subunit, moderate affinity for GABAA receptors containing α2 or α3 subunits, and a very low affinity for GABAA receptors containing α5 subunit (Crestani et al., 2000; Rudolph, 2001). Zolpidem can enhance the GABA-mediated phasic current (Iphasic) by prolonging the IPSC decay time constant, and in some instances, increasing the amplitude and/or frequency of the post-synaptic GABAergic IPSC (Chen et al., 2007; Defazio and Hablitz, 1998; Perrais and Ropert, 1999), but effects on the tonic GABA current (Itonic) are variable. In many cell types, Itonic is unaffected by zolpidem or benzodiazepines (Cope et al., 2005; Jia et al., 2005; Nusser and Mody, 2002), but in other cells, the Itonic is enhanced by benzodiazepines, suggesting receptors with α1–3 subunit composition are involved in Itonic modulation (Bouairi et al., 2006; Semyanov et al., 2003; Yeung et al., 2003). In DMV neurons, besides well-studied GABA-mediated synaptic currents underlying Iphasic, two types of GABAA receptor-mediated Itonic with different pharmacological properties have been identified (Gao and Smith, 2010). Considering the importance of GABAA receptors in the normal function of DMV and the critical regulatory role these neurons play, we investigated the effects of zolpidem on the Iphasic and Itonic to elucidate the different GABAA receptors involving in controlling these currents in the DMV.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Brainstem slice preparation

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), 4–8 weeks of age, were housed under a standard 12-h light/dark cycle, with food and water provided ad libitum. All animals were treated and cared for in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and all procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committees at Tulane University and the University of Kentucky. Rats were deeply anesthetized with halothane (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) or isoflurane (Minrad, Buffalo, NY) inhalation and then decapitated while anesthetized. The brain was removed and blocked on an ice-cold stand, and the medulla and cerebellum were glued to a sectioning stage. Transverse brainstem slices (300–400 μm) containing DMV were made in 0–2 °C, oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) artificial cerebro-spinal fluid (ACSF) using a vibrating microtome (Vibratome Series 1000; Technical Products, Intl., St. Louis, MO). The ACSF contained (in mM): 124 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 11 glucose and 1 kynurenic acid; pH 7.2–7.4, with an osmolality of 290–315 mOsm/kg. Slices were then incubated for at least 1 h in warm (33–35 °C), oxygenated ACSF. For recording, a single brain slice was transferred to a chamber mounted on a fixed stage under an upright microscope (Olympus BX51WI; Melville, NY), where it was continually superfused by warmed, oxygenated ACSF.

2.2. Electrophysiological recording

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were obtained in the DMV using pipettes with open tip resistances of 3–5 MΩ. Recording pipettes were pulled from boro-silicate glass (Garner Glass Co., Claremont, CA, USA). The intracellular pipette solution for most recordings contained (in mM): 130 Cs-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 1 NaCl, 1 CaCl2, 3 CsOH, 5 EGTA, 2–4 Mg–ATP, 0.1% biocytin. Biocytin was included to confirm the cell location within the DMV and to verify that cellular morphology was consistent with that of motor neurons (Gao et al., 2009). In some experiments, the intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM): 130–140 K-gluconate or 130 KCl instead of Cs–gluconate, with KOH instead of CsOH. Neurons in the DMV were targeted for recording under a 40× water-immersion objective (NA = 0.8) with infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) optics, as previously described (Davis et al., 2003; Derbenev et al., 2004).

Electrophysiological signals were obtained using an Axopatch 200B amplifier or 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA), digitized at 88 kHz (Neurocorder, Cygnus Technology, Delaware Water Gap, PA) and low pass filtered at 2–5 kHz, recorded onto videotape and to a computer (Digidata 1320A, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) using Clampex 8.2 or 10.1 software (Molecular Devices). Recordings were analyzed with pClamp 10.0 software (Molecular Devices) or MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA). Seal resistance was typically 2–5 GΩ, and series resistance, measured from brief voltage steps (5 mV, 5 ms) applied through the recording pipette, was typically <25 MΩ and was monitored periodically during the recording. Recordings were discarded if series resistance changed by more than 20% over the course of experiment. Input resistance was measured in current-clamp recording mode by injecting current-steps (10 pA, 400 ms; K-gluconate intracellular solution). When in voltage-clamp, resting membrane potential was checked periodically during the recording by monitoring the voltage at which no current was injected.

For IPSCs, neurons were voltage-clamped at –10 mV (Cs-gluconate) or –50 to –70 mV (KCl solution). Kynurenic acid (1 mM) was added to the ACSF for all experiments to block EPSCs. Pressure application of muscimol, a GABAA receptor agonist, was done by using a picospritzer (General Valve). Lidocaine N-ethyl bromide (QX314; 5 μM) was included in intracellular solution to block voltage-gated Na+ currents in pressure microapplication experiments. Muscimol (100 μM) was dissolved in ACSF and was delivered at intervals of 10 s via a second patch pipette positioned close to the cell soma (6–20 psi; 4–6 ms; 20–50 μm from the soma). All drugs were obtained from Sigma, Tocris or Fisher. TTX (1 μM), zolpidem (0.01–30 μM), flumazenil (10 μM), bicuculline methiodide (30 μM), gabazine (0.5 μM) and nipecotic acid (1 mM) were added to ACSF for specific experiments. All values are shown as mean ± SEM.

2.3. Data analysis

IPSCs were analyzed with MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA) to measure the peak amplitude, frequency, 10–90% rise time, and the decay time constant. Curve fitting was performed on averaged IPSCs (>50 events) using the bi-exponential equation from MiniAnalysis, y = A1exp (–t/τ1) + A2exp (–t/τ2). In this equation, y is the peak amplitude, A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of the fast and slow decay components, and τ1 and τ2 are the corresponding decay time constants of A1 and A2 (Yeung et al., 2003). We used a weighted time constant to compare decay times between different experimental conditions. The weighted time constant of current decay times was calculated with the equation τw = ΣAiτi/ΣAi (Banks and Pearce, 2000; Yeung et al., 2003). The amplitude of the tonic current (Itonic) was calculated as the difference between the steady-state holding current before and after application of bicuculline (30 μM) or picrotoxin (50 μM). The holding current was analyzed using the mean of 100 ms segments free of sIPSCs (n = 30) taken every 1 s for 30 s before and after drug treatment. Taking the mean of 30 baseline points, allowed an average baseline holding current to be measured (Keros and Hablitz, 2005; Nusser and Mody, 2002). Resting membrane potential was similarly obtained by combining 100–500 ms samples of voltage (30 s total) taken between action potentials, when necessary. Electrophysiological comparisons between the groups before and after drug treatment were made with two-tailed Student's t tests. Significance for all measures was set at p < 0.05. Statistical measurements were performed with Synaptosoft or Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) programs. Numbers are expressed as mean standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise indicated.

3. Results

3.1. The effects of zolpidem on mIPSCs

The effects of zolpidem on reversed IPSCs (i.e., KCl intracellular; Vm = –50 to –70 mV) were measured in the presence of kynurenic acid (1 mM) and tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 mM). Under these control conditions the average amplitude of mIPSCs was 43.2 ± 3.0 pA, the frequency was 1.9 ± 0.3 Hz; the 10–90% rise time of averaged mIPSCs was 2.6 ± 0.2 ms, and the weighted decay time was 13.2 ± 1.1 ms (n = 28). The decay time of mIPSCs was fitted well with single exponential curve in 23/28 recordings; while in the remaining recordings, mIPSCs were better fitted with two-exponential decay times. Bath application of zolpidem resulted in a concentration-dependent (0.1–30 μM) enhancement of the decay time constant of mIPSCs without a significant change in mIPSCs frequency or 10–90% rise time (Fig. 1). The amplitude of mIPSCs was enhanced at a single concentration of zolpidem (10 μM), but this was limited to only a few cells and was not observed at any other dose. In general, mIPSC amplitude was unaffected by zolpidem.

Fig. 1.

Effects of bath application of zolpidem on tetrodotoxin (TTX)-resistant mIPSCs recorded in DMV neurons. A. Recordings of mIPSCs before and during the application of zolpidem (1 μM). B. Averaged mIPSCs in control ACSF and in the presence of zolpidem (1 μM; arrow). C. Averaged mIPSCs in flumazenil (10 μM) and with addition of zolpidem (1 μM). D. Effects of zolpidem (0.01–30 μM) on mIPSC amplitude (D1), frequency (D2), rise time (D3) and weighted decay time (D4). The values obtained in different concentrations of zolpidem are plotted as ratios over control values measured within each recording; each point represents the mean ± SEM of 5–6 neurons. Asterisks indicate significant change in zolpidem versus measurements in control ACSF (p < 0.05). Kynurenic acid (1 mM) and TTX (1 μM) were present for all recordings.

The effects of zolpidem were comparable to those of flunitrazepam (5 μM), a broad-spectrum benzodiazepine that interacts with GABAA receptors containing α1/2/3 and α5 subunits. Flunitrazepam significantly prolonged the decay time constant of sIPSCs from 11.7 ± 1.3 ms to 20.4 ± 2.2 ms (p < 0.05; n = 11) without significant change in sIPSC amplitude (53.8 ± 6.3 pA and 47.9 ± 6.0 pA respectively; p > 0.05; n = 11), frequency (1.7 ± 0.4 Hz and 0.9 ± 0.2 Hz respectively; p > 0.05; n = 11), or 10–90% rise time (1.9 ± 0.2 ms and 2.2 ± 0.2 ms respectively; p > 0.05; n = 11).

The benzodiazepine receptor antagonist flumazenil was used to further test the hypothesis that the effects of zolpidem on synaptic currents were caused by binding at the benzodiazepine site. In the presence of flumazenil (10 μM) the amplitude, frequency, 10–90% rise time, and the weighted decay time constant of mIPSCs were not significantly changed by zolpidem 1 μM (p > 0.05; n = 7; Fig. 1C).

3.2. The effects of zolpidem on muscimol-evoked currents

Changes in GABA release and GABA uptake can alter the decay of synaptic currents (Nusser and Mody, 2002; Farrant and Nusser, 2005). Muscimol is a selective GABAA receptor agonist with abinding affinity similar to that of GABA, but muscimol cannot be transferred across the membrane by GABA transporters (Ebert et al., 1997). Pressure microapplication of muscimol to the recorded cell (100 μM) was used to test muscimol-evoked currents at various membrane potentials. The results indicated a reversal potential for the muscimol current of around –6 mV, which was close to the calculated chloride equilibrium potential (0 mV; Fig. 2A). Adding bicuculline (50 μM) completely blocked the currents evoked by pressure-applied muscimol (Fig. 2B). These data demonstrated that the muscimol-evoked currents were mediated by GABAA receptors, which gate Cl– channels. Zolpidem (1 μM) significantly prolonged the decay time constant (tau) of currents evoked by muscimol (p < 0.05; n = 6) without significantly changing the current amplitude (p > 0.05; Fig. 2C). This suggested that the increase in decay time constant of IPSCs mediated by synaptic GABAA receptors was not due to altered GABA uptake, but rather to the effect of zolpidem at benzodiazepine binding sites, to increase the affinity of GABAA receptors (Defazio and Hablitz, 1998; Perrais and Ropert, 1999).

Fig. 2.

Effect of zolpidem on muscimol-evoked currents. A. Muscimol microapplication evoked whole-cell currents at various membrane potentials. Each trace represents the average of three to five responses to muscimol. Traces shown at holding potentials of –60, –30, 0, 15 mV, and 30 mV; KCl intracellular solution. Bottom, I–V curve of the peak currents evoked at each holding potential. B. The current evoked by muscimol (100 μM) was blocked by bath-applied bicuculline (50 μM). C. The muscimol-evoked currents were examined before and after bath application of zolpidem (1 μM). Bottom, summary graph (n = 6) of the effects of zolpidem on the peak current and decay time constant (τ) of currents evoked by muscimol. Asterisk indicates significance versus currents evoked by muscimol in control ACSF (p < 0.05). Cell was voltage-clamped at –60 mV for experiments in B and C.

3.3. The effects of zolpidem on the Itonic and action potential frequency

Bath application of bicuculline (30 μM) revealed a tonic GABAA receptor-mediated current (i.e., Itonic) in DMV neurons. To determine if zolpidem altered the GABAA receptor-mediated Itonic, zolpidem was applied while assessing steady-state current in voltage-clamp mode. Bath application of zolpidem (1 μM) changed the Itonic by less than 5 pA in each of six DMV neurons. The average increase in Itonic by zolpidem in these neurons was 1.6 ± 0.8 pA. Overall no significant difference between the baseline Itonic and the Itonic in zolpidem was observed (29.1 ± 6.7 pA and 30.7 ± 6.3 pA respectively; p > 0.05; n = 6; Fig. 3A, B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of zolpidem on tonic GABA current (Itonic) and action potential firing activity in DMV neurons. A. Bath application of zolpidem (1 μM) did not significantly change the baseline holding current. Addition of bicuculline (30 μM) revealed the GABAA receptor-mediated Itonic. B. Graph showing the Itonic amplitude in control ACSF and after addition of zolpidem (1 μM) to ACSF. Number of replicates in parentheses. C. Current-clamp recording at resting membrane potential showing that zolpidem (1 μM) decreased the action potential frequency and bicuculline (30 μM) reversed the effects caused by zolpidem. D, E. Histograms showing the effects of zolpidem and bicuculline on the resting membrane potential (D) and action potential firing frequency (E) in DMV neurons. Asterisks indicate significant change between groups (p < 0.05). Number of replicates in parentheses.

In current-clamp recordings, zolpidem (1 μM) application significantly suppressed the action potential firing activity. The action potential frequency was 1.2 ± 0.4 Hz in control at resting membrane potential, and it was decreased to 0.9 ± 0.3 Hz by zolpidem (paired t-test; p < 0.05; n = 17; Fig. 3C, E). Bicuculline (30 μM) reversed the effects caused by zolpidem, increasing the frequency to 1.1 ± 0.3 Hz (p < 0.05; n = 17). The resting membrane potential was hyperpolarized (>2 mV) by zolpidem (1 μM) in 10 of 17 DMV neurons. The average resting membrane potential changed from –50.2 ± 1.6 mV to –53.2 ± 1.4 mV in the presence of zolpidem in these 10 DMV neurons (p < 0.05; Fig. 3D). Resting membrane potential was unchanged in the other 7 neurons. Bicuculline (30 μM) depolarized the resting membrane potential to –48.7 ± 1.5 mV (p < 0.05; n = 17; Fig. 3D). Bath application of zolpidem (1 μM) aslo decreased the input resistance in whole-cell current-clamp recordings from 789 ± 38 M Ω to 710 ± 33 MΩ (p < 0.05; n = 9; Fig. 4A–C). Whole-cell input resistance recovered subsequent to bicuculline (30 μM) application (831 ± 47 MΩ). Although zolpidem had no significant effect on resting Itonic, it reduced the action potential firing activity and hyperpolarized the membrane potential of most neurons.

Fig. 4.

Zolpidem decreased the input resistance in whole-cell current-clamp recordings. A. Current-clamp recording from a DMV neuron showing a decreased voltage response to current-steps injection after zolpidem (1 μM) application; bicuculline (30 μM) reversed the effect of zolpidem. B. Bar graph showing a decrease in input resistance caused by zolpidem in 9 DMV neurons, and a reversal of the effect with bicuculline. Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups indicated (p < 0.05). Number of replicates in parentheses. C. Current versus voltage (I–V) plot from the same DMV neuron in A illustrating the decrease in slope input resistance after zolpidem perfusion. Bic, bicuculline.

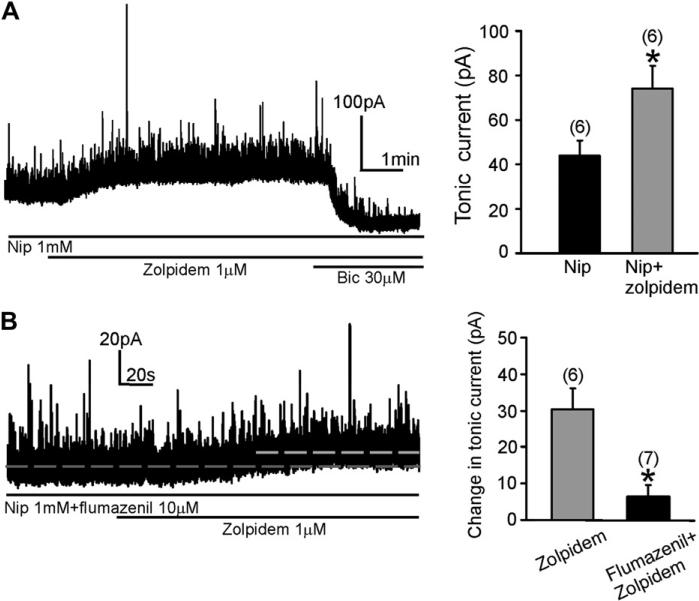

3.4. Nipecotic acid uncovered a zolpidem-induced increase in Itonic

The concentration of extracellular GABA can be elevated by adding exogenous GABA or by increasing endogenous GABA with GABA uptake inhibitors (Bai et al., 2001; Nusser and Mody, 2002; Semyanov et al., 2003). When the non-selective GAT antagonist nipecotic acid (1 mM) was applied to ACSF, it significantly enhanced the Itonic in DMV neurons, revealed by application of bicuculline (30 μM)(Gao and Smith, 2010). Application of zolpidem (1 μM) generated a significant enhancement of the Itonic in the continued presence of nipecotic acid (p < 0.05; n = 6; Fig. 5A). The Itonic was 43.7 ± 7.0 pA in nipecotic acid and 74.0 ± 10.5 pA after addition of zolpidem. Preapplication of flumazenil (10 μM) suppressed the zolpidem-induced increase in Itonic amplitude observed in the presence of nipecotic acid. In the presence of nipecotic acid, the increase in Itonic induced by zolpidem was 30.3 ± 5.7 pA (n = 6), whereas in the added presence of flumazenil it was 6.3 ± 3.2 pA (n = 7; Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Zolpidem increased the Itonic in DMV neurons in the presence of nipecotic acid. A. In the presence of nipecotic acid (1 mM), application of zolpidem (1 μM) significantly enhanced the amplitude of Itonic. Right, graph showing the Itonic amplitude after adding zolpidem to the nipecotic acid-containing ACSF. Asterisk indicates significant change in current versus nipecotic acid alone (p < 0.05). Number of replicates in parentheses. B. The increase in Itonic amplitude induced by zolpidem in the presence of nipecotic acid was largely suppressed by application of flumazenil (10 μM). Right, summary graph shows the Itonic amplitude changes induced by zolpidem in the presence and absence of flumazenil. Both groups obtained from nipecotic acid-containing ACSF. Asterisk indicates significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05). Nip, nipecotic acid; Bic, bicuculline.

Gabazine is a competitive GABAA receptor antagonist with affinity for the synaptic GABAA receptors (Bai et al., 2001; Semyanov et al., 2003; Yeung et al., 2003). We tested whether the effect of zolpidem on Itonic in nipecotic acid (1 mM) was abolished when gabazine 0.5 μM was pre-applied into ACSF. Zolpidem (1 μM) produced a small increase on Itonic in 5/10 DMV neurons in the presence of gabazine (0.5 μM). The average increase in these neurons was 10.2 ± 1.4 pA (n = 5; Fig. 6A, B). This increase was significantly less (p < 0.05) than the Itonic change induced by zolpidem in the presence of nipecotic acid alone (i.e., without gabazine). The remaining neurons (5/10) were not responsive to zolpidem in the presence of gabazine. The average change was 0.5 ± 0.8 pA in this group (p < 0.05 compared to the first group; Fig. 6A, B). Overall, the average zolpidem-induced increase in Itonic amplitude in the presence of both gabazine and zolpidem was 5.4 ± 1.8 pA (n = 10). Gabazine inhibited the effect of zolpidem, although there was a gabazine-insensitive component of zolpidem's effect in a subset of neurons.

Fig. 6.

Two different responses to zolpidem in gabazine-containing ACSF. A. In the presence of nipecotic acid (1 mM) and gabazine (0.5 μM), the effect of zolpidem (1 μM) on holding current was either partially maintained (upper trace) or blocked (lower trace). B. Comparison of the zolpidem effect on Itonic in the gabazine-attenuated and the gabazine-blocked groups. Asterisk indicates significant difference between gabazine treatment groups (p < 0.05). Number of replicates in parentheses. Bic, bicuculline; GBZ, gabazine; Nip, nipecotic acid.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates the effects of zolpidem on GABAA receptor-mediated phasic synaptic currents and extra-synaptic tonic currents in DMV neurons. Zolpidem prolonged the decay time of mIPSCs and muscimol-evoked whole-cell GABA currents. The effects were blocked by flumazenil. Zolpidem did not clearly alter the Itonic under baseline conditions, but after elevating the extracellular GABA concentration with a non-selective GAT blocker, zolpidem markedly enhanced the Itonic. This increase was suppressed by the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil and the GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine in subsets of neurons. Effects of zolpidem on both Itonic and Iphasic suggest receptors containing α1–3 subunits are involved in both synaptic and tonic GABA responses.

A plurality of DMV neurons projects to postganglionic neurons innervating the gastric mucosa. GABAA receptors play a critical role in regulating DMV neuron excitability and gastrointestinal activities (Davis et al., 2004; Sivarao et al., 1998; Travagli et al., 2006). Both Iphasic and Itonic are evident in DMV, which are mediated by distinct pools of GABAA receptors. Both currents can be modulated by widely used drugs, including anticonvulsants and hypnotics. Benzodiazepines are efficient against seizures, and are also used as sedative and sleep medicines clinically. Among their side effects are cough, hiccups, nausea and vomiting (Nordt and Clark, 1997). Paradoxically, benzodiazepines can be used to treat nausea and vomiting at doses lower than for the hypnotic effects (Jordan et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007; Tarhan et al., 2007) and these effects may be mediated by altering temporally relevant synaptic signals in the vagal complex. The effects of zolpidem in the DMV are consistent with effects of the drug on gastrointestinal function.

Zolpidem is a non-benzodiazepine drug that interacts with benzodiazepine site on GABAA receptors, which is located on the interface between α and γ2 subunits to potentiate the activity of GABAA receptors (Barnard et al., 1998; Mohler et al., 2002; Rudolph et al., 2001). Zolpidem has high affinity for the GABAA receptors containing α1 subunit. The drug also has moderate affinity for the receptors containing α2 or α3 subunits, but has very low affinity for receptors containing α5 subunit and virtually no affinity for GABAA receptors containing α4, α6, δ and ε subunits (Barnard et al., 1998; Mohler et al., 2002; Rudolph et al., 2001). The actions of zolpidem are not only restricted to the sleep centers in brain; it has potentially more widespread effects due to the wide expression of α1–3 subunits (Harrison, 2007).

Our data support the hypothesis that zolpidem effects on GABAergic IPSCs are mainly mediated by GABAA receptors containing α1 subunits, but involvement of receptors containing α2 and α3 subunits cannot be ruled out. The α1 subunit is the most highly expressed a subunit in the medulla (Pirker et al., 2000). In the DMV, the mRNAs of GABAA α1 subunits are expressed and GABAA α1-IR are distributed evenly throughout the DMV (Broussard et al., 1997), consistent with an effect of zolpidem on GABAA–mediated currents. Expression of α2 and α3 subunits is high during early postnatal period in rats and mice, but the expression decreases significantly during the first month of life. At the same time, α1 expression increases and synaptic GABAergic currents become much faster (Okada et al., 2000; Vicini et al., 2001). The weighted decay time of mIPSCs in our recording is about 13 ms, which is very close to the decay time reported for other neurons containing α1 GABAA receptors (Defazio and Hablitz, 1998; Goldstein et al., 2002; Okada et al., 2000; Vicini et al., 2001). When the GABAA receptors contain α2 or α3 subunits, the IPSC decay time constant is much slower – around 30–50 ms (Gingrich et al., 1995; Goldstein et al., 2002; Okada et al., 2000; Verdoorn, 1994; Vicini et al., 2001). The efficacy of zolpidem at the α2 or α3 containing GABAA receptors (EC50 ≈ 500–800 nM) is much lower than for effects on α1 subunit-containing receptors (EC50 ≈ 100 nM; Lindquist and Birnir, 2006). In our recordings, zolpidem prolonged the weighted decay time of mIPSCs in a concentration-dependent manner, but the effect was minor at concentrations below 1 μM. From our data, the estimated EC50 for the effect of zolpidem on the weighted decay time for mIPSCs in the DMV is about 5 μM, which is much higher than the EC50 (i.e., ~100 nM) for a pure α1 effect (Lindquist and Birnir, 2006). The γ2 subunit is required for natural clustering of postsynaptic GABAA receptors and γ2 are typically associated with synaptic receptors (Mohler et al., 2002; Rudolph et al., 2001; Vicini and Ortinski, 2004). The α5 subunit-containing GABAA receptors are probably not expressed in synapses; they have very low affinity for zolpidem, and require relatively high concentrations (>10 μM) to be potentiated (Goldstein et al., 2002). Our data suggest a mixed response that may involve α1–3 and γ2 subunit-containing receptors.

Flumazenil, a benzodiazepine binding site antagonist, blocked the effects of zolpidem on the mIPSC decay time constant, supporting the hypothesis that zolpidem interacts with the benzodiazepine site. The prolongation of the decay time constant by zolpidem may have been due to the increase in the affinity for GABA after zolpidem binding, which results in reduced unbinding rate for GABA (Chen et al., 2007; Defazio and Hablitz, 1998; Perrais and Ropert, 1999). Alternatively, the frequency of Cl– channel opening mediated by GABAA receptors was increased after zolpidem acting on benzodiazepine site in other cells (Chen et al., 2007; Defazio and Hablitz, 1998; Rogers et al., 1994), and this could also potentiate GABA effects.

The decay time of synaptic currents can be influenced by increased GABA concentration due to enhanced GABA release and decreased GABA uptake (Keros and Hablitz, 2005; Rossi and Hamann, 1998; Semyanov et al., 2003; Wei et al., 2003). In our studies, we added TTX to prevent the influence of spike-dependent changes in presynaptic GABA release and recorded muscimol-evoked postsynaptic currents in the recorded cell. Muscimol cannot be transported by GATs, which excludes any impact of altered GABA re-uptake on the decay time constant. The decay time constant of muscimol-evoked currents was increased by zolpidem, supporting the conclusion that zolpidem increases GABA binding efficacy (Chen et al., 2007; Defazio and Hablitz, 1998; Perrais and Ropert, 1999).

Under baseline conditions, zolpidem (1 μM) mainly acted at synaptic receptors to increase the affinity for GABA, but interacted less effectively with extrasynaptic GABAergic receptors mediating Itonic. This argues against the possibility that the mIPSC prolongationwas due to zolpidem actions on extrasynaptic receptors. Since the Itonic was not significantly altered under control conditions, we interpret the change in excitability observed in current-clamp mode to be due mainly to activity at synaptic receptors. However, other explanations should also be considered, including the possibility that extrasynaptic receptors at an electrotonic distance from the recording could contribute to the hyperpolarization seen in current-clamp recordings. In addition, although it was negligible overall, a zolpidem induced a small change (2–5 pA) in three of the six neurons tested and a current of this amplitude could conceivably affect membrane potential enough to reduce firing. By binding to synaptic or possibly extrasynaptic receptors and enhancing GABA efficacy, zolpidem decreased the excitability of DMV neurons and reduced the input resistance.

Zolpidem does not affect GABAA receptors without concomitant GABA binding (Bai et al., 2001; Lavoie and Twyman, 1996). So under baseline conditions, the Itonic in DMV neurons may be mediated by GABAA receptors that contain subunits other than those found at the synapse. This part of the Itonic may be mediated by high-affinity GABAA receptors, which are dissimilar to the low-affinity synaptic GABAA receptors(Gao and Smith, 2010). Under conditions of elevated extracellular GABA levels (i.e., in the presence of nipecotic acid), zolpidem consistently enhanced the Itonic, suggesting that, like synaptic receptors, a subset of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors also consists of low-affinity α1/2/3 and γ2-containing subunits, because zolpidem effects require γ2 and α subunit expression (Harrison, 2007; Mohler et al., 2002; Rudolph et al., 2001). This is consistent with our previous work indicating that Itonic has at least two components in the DMV, one that is apparent at low ambient GABA concentrations and is likely due to binding of high-affinity receptors and another that is due to binding of lower affinity receptors and is prominent when GABA concentration is elevated (Gao and Smith, 2010). Zolpidem appears to affect low-affinity synaptic and also extrasynaptic receptors when GABA is elevated. Although nipecotic acid increases Itonic significantly, it has no effect on IPSC amplitude or time constant, consistent with the hypothesis that any Itonic mediated by low-affinity receptors is not simply the result of summated IPSCs.

Low concentrations of gabazine block IPSCs and the components of the Itonic that are mediated by low-affinity GABAA receptors. Yet, some DMV neurons responded to zolpidem in the presence of nipecotic acid and gabazine. The persistent response of a subset of DMV cells to zolpidem in the presence of GABA transporter inhibitors and gabazine was similar to previous findings in a subset of hippocampal neurons (Semyanov et al., 2003). As in hippocampal neurons, DMV cells may express a subset of extrasynaptic GABA receptors containing gabazine-insensitive δ subunits in addition to gabazine-sensitive γ subunits.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that zolpidem affects phasic and tonic GABA currents by binding to distinct synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAA receptor pools in DMV neurons. This may provide useful information about how zolpidem and benzodiazepines influence visceral autonomic functions by affecting activity of the neurons in DMV.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from NSF IOB-0518209 and NIH (DK056132).

References

- Bai D, Zhu G, Pennefather P, Jackson MF, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Distinct functional and pharmacological properties of tonic and quantal inhibitory postsynaptic currents mediated by gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors in hippocampal neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:814–824. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MI, Pearce RA. Kinetic differences between synaptic and extra-synaptic GABA(A) receptors in CA1 pyramidal cells. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:937–948. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-03-00937.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, Braestrup C, Bateson AN, Langer SZ. International Union of Pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors: classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouairi E, Kamendi H, Wang X, Gorini C, Mendelowitz D. Multiple types of GABAA receptors mediate inhibition in brain stem parasympathetic cardiac neurons in the nucleus ambiguus. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;96:3266–3272. doi: 10.1152/jn.00590.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broussard DL, Li H, Altschuler SM. Colocalization of GABA(A) and NMDA receptors within the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMV) of the rat. Brain Res. 1997;763:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Xie JX, Fung KS, Yung WH. Zolpidem modulates GABA(A) receptor function in subthalamic nucleus. Neurosci. Res. 2007;58:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope DW, Hughes SW, Crunelli V. GABAA receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in thalamic neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:11553–11563. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3362-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crestani F, Martin JR, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Mechanism of action of the hypnotic zolpidem in vivo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;131:1251–1254. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SF, Derbenev AV, Williams KW, Glatzer NR, Smith BN. Excitatory and inhibitory local circuit input to the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus originating from the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res. 2004;1017:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SF, Williams KW, Xu W, Glatzer NR, Smith BN. Selective enhancement of synaptic inhibition by hypocretin (orexin) in rat vagal motor neurons: implications for autonomic regulation. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3844–3854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03844.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defazio T, Hablitz JJ. Zinc and zolpidem modulate mIPSCs in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1670–1677. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbenev AV, Stuart TC, Smith BN. Cannabinoids suppress synaptic input to neurones of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. J. Physiol. 2004;559:923–938. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.067470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert B, Thompson SA, Saounatsou K, McKernan R, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Wafford KA. Differences in agonist/antagonist binding affinity and receptor transduction using recombinant human gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:1150–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:215–219. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Glatzer NR, Williams KW, Derbenev AV, Liu D, Smith BN. Morphological and electrophysiological features of motor neurons and putative interneurons in the dorsal vagal complex of rats and mice. Brain Res. 2009;1291:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Smith BN. Tonic GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;103:904–914. doi: 10.1152/jn.00511.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich KJ, Roberts WA, Kass RS. Dependence of the GABAA receptor gating kinetics on the alpha-subunit isoform: implications for structureefunction relations and synaptic transmission. J. Physiol. 1995;489:529–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PA, Elsen FP, Ying SW, Ferguson C, Homanics GE, Harrison NL. Prolongation of hippocampal miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents in mice lacking the GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subunit. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3208–3217. doi: 10.1152/jn.00885.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison NL. Mechanisms of sleep induction by GABA(A) receptor agonists. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl. 5):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia F, Pignataro L, Schofield CM, Yue M, Harrison NL, Goldstein PA. An extrasynaptic GABAA receptor mediates tonic inhibition in thalamic VB neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:4491–4501. doi: 10.1152/jn.00421.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Kasper C, Schmoll HJ. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: current and new standards in the antiemetic prophylaxis and treatment. Eur. J. Cancer. 2005;41:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keros S, Hablitz JJ. Subtype-specific GABA transporter antagonists synergistically modulate phasic and tonic GABAA conductances in rat neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2073–2085. doi: 10.1152/jn.00520.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie AM, Twyman RE. Direct evidence for diazepam modulation of GABAA receptor microscopic affinity. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Wang JJ, Yang YL, Chen A, Lai HY. Midazolam vs ondansetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist CE, Birnir B. Graded response to GABA by native extrasynaptic GABA receptors. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:1349–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H, Fritschy JM, Rudolph U. A new benzodiazepine pharmacology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;300:2–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordt SP, Clark RF. Midazolam: a review of therapeutic uses and toxicity. J. Emerg. Med. 1997;15:357–365. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(97)00022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Mody I. Selective modulation of tonic and phasic inhibitions in dentate gyrus granule cells. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2624–2628. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M, Onodera K, Van Renterghem C, Sieghart W, Takahashi T. Functional correlation of GABA(A) receptor alpha subunits expression with the properties of IPSCs in the developing thalamus. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2202–2208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-06-02202.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrais D, Ropert N. Effect of zolpidem on miniature IPSCs and occupancy of postsynaptic GABAA receptors in central synapses. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:578–588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00578.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirker S, Schwarzer C, Wieselthaler A, Sieghart W, Sperk G. GABA(A) receptors: immunocytochemical distribution of 13 subunits in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2000;101:815–850. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CJ, Twyman RE, Macdonald RL. Benzodiazepine and beta-carboline regulation of single GABAA receptor channels of mouse spinal neurones in culture. J. Physiol. 1994;475:69–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RC, McTigue DM, Hermann GE. Vagal control of digestion: modulation by central neural and peripheral endocrine factors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1996;20:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00040-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Hamann M. Spillover-mediated transmission at inhibitory synapses promoted by high affinity alpha6 subunit GABA(A) receptors and glomerular geometry. Neuron. 1998;20:783–795. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U. Identification of molecular substrate for the attenuation of anxiety: a step toward the development of better anti-anxiety drugs. Scientific World J. 2001;1:192–193. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2001.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Crestani F, Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor subtypes: dissecting their pharmacological functions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001;22:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semyanov A, Walker MC, Kullmann DM. GABA uptake regulates cortical excitability via cell type-specific tonic inhibition. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:484–490. doi: 10.1038/nn1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivarao DV, Krowicki ZK, Hornby PJ. Role of GABAA receptors in rat hindbrain nuclei controlling gastric motor function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 1998;10:305–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1998.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarhan O, Canbay O, Celebi N, Uzun S, Sahin A, Coskun F, Aypar U. Subhypnotic doses of midazolam prevent nausea and vomiting during spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. Minerva. Anestesiol. 2007;73:629–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Gillis RA, Rossiter CD, Vicini S. Glutamate and GABA-mediated synaptic currents in neurons of the rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Am. J. Physiol. 1991;260:G531–G536. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.3.G531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travagli RA, Hermann GE, Browning KN, Rogers RC. Brainstem circuits regulating gastric function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2006;68:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040504.094635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA. Formation of heteromeric gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors containing two different alpha subunits. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicini S, Ferguson C, Prybylowski K, Kralic J, Morrow AL, Homanics GE. GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subunit deletion prevents developmental changes of inhibitory synaptic currents in cerebellar neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:3009–3016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-09-03009.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicini S, Ortinski P. Genetic manipulations of GABAA receptor in mice make inhibition exciting. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;103:109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washabau RJ, Fudge M, Price WJ, Barone FC. GABA receptors in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus influence feline lower esophageal sphincter and gastric function. Brain Res. Bull. 1995;38:587–594. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)02038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Zhang N, Peng Z, Houser CR, Mody I. Perisynaptic localization of delta subunit-containing GABA(A) receptors and their activation by GABA spillover in the mouse dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:10650–10661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10650.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung JY, Canning KJ, Zhu G, Pennefather P, MacDonald JF, Orser BA. Tonically activated GABAA receptors in hippocampal neurons are high-affinity, low-conductance sensors for extracellular GABA. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:2–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]