Abstract

Background

The continuation of developing HSV-2 prophylactic vaccines requires parallel mathematical modeling to quantify the impact on the population of these vaccines.

Methods

Using mathematical modeling we derived three summary measures for the population impact of imperfect HSV-2 vaccines as a function of their efficacies in reducing susceptibility (VES), genital shedding (VEP), and infectivity during shedding (VEI). In addition, we studied the population level impact of vaccine intervention using representative vaccine efficacies.

Results

A vaccine with limited efficacy of reducing shedding frequency (VEP =10%) and infectivity (VEI =0%) would need to reduce susceptibility by 75% (VES =75%) to substantially reduce the sustainability of HSV-2 infection in a population. No reduction in susceptibility would be required to reach this target in a vaccine that decreased shedding by 75% (VES =0%, VEP =75%, VEI =0%). Mass vaccination using a vaccine with imperfect efficacies (VES =30%, VEP =75%, and VEI =0%) in Kisumu, Kenya in 2010 would decrease prevalence and incidence in 2020 by 7% and 30% respectively. For lower prevalence settings, vaccination is predicted to have a lower impact on prevalence.

Conclusion

A vaccine with substantially high efficacy of reducing HSV-2 shedding frequency would have a desirable impact at the population level. The vaccine’s short-term impact in a high prevalence setting in Africa would be a substantial decrease in incidence, whereas its immediate impact on prevalence would be small and would increase slowly over time.

Keywords: Keywords: Herpes simplex virus, mathematical modeling, prophylactic vaccines, summary measures, vaccine efficacy

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2) infection is highly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa [1–10] and around the globe [11–13]. The broad spread of HSV-2 is further complicated by the common mode of transmission and the synergistic epidemiologic pattern that it shares with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). HSV-2 positive and HSV-2/HIV co-infected persons have a higher risk of contracting HIV infection [14–16], and of transmitting HIV [17, 18], respectively. The estimated proportion of HIV infections attributable to HSV-2 in areas with a high HSV-2 prevalence such as sub-Saharan Africa is approximately 25% [19]. Therefore, controlling HSV-2 could have a substantial population-level impact on HIV incidence in sub-Saharan Africa.

HSV-2 vaccines have gained more focus after the recent failure of HSV-2 suppression therapy to limit HIV spread in three randomized-controlled trials [20–22]. An ideal HSV-2 prophylactic vaccine would induce sterilizing immunity and prevent HSV-2 acquisition in susceptible populations. Meanwhile, imperfect [23] prophylactic HSV-2 vaccines could partially reduce HSV-2 acquisition in vaccinees, and/or partially reduce infectivity of those who get infected after vaccination, by either reducing their shedding frequency or viral load during shedding episodes. Because the effectiveness of a licensed vaccine is not known, mathematical modeling can determine the population-level impact of various combinations of protection regarding three biologic aspects of disease: susceptibility, shedding frequency, and infectivity while shedding.

Two prophylactic recombinant vaccines have completed phase III clinical trials and achieved limited success in protecting against HSV-2 acquisition [24–26]. A third vaccine that uses the full-length of gD with bupivacaine recently underwent successful testing in a safety and immunogenicity trial [27].

Because the current HSV-2 strategies target reduction in shedding as a primary outcome along with the classical target of susceptibility reduction [26, 28], the results of future clinical trials of vaccines will provide vaccine efficacies in terms of reduction in susceptibility and shedding frequency. These efficacies are obtained for individuals during the short period of the clinical trial. Therefore, the criteria for a favorable vaccine at the population level will not be directly obtained from these trials.

Our goal in this study was to estimate the population-level impacts of prophylactic HSV-2 vaccines using mathematical modeling. We introduced a model for HSV-2 in which the different aspects of prophylactic HSV-2 vaccines were parameterized to study their effects. While previous HSV-2 models [29, 30] studied population-level impact of HSV-2 vaccines in the United States, we estimated the impact of vaccination at the population level in a representative setting of hyperendemic HIV and HSV-2 epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa (Kisumu, Kenya). The impact of vaccination was estimated in terms of impact on prevalence, incidence, and infections averted per vaccination procedure.

Materials and Methods

We constructed a deterministic compartmental model calibrated to describe HSV-2 transmission in presence of vaccination in different populations but focused most of our analyses on a representative sub-Saharan African population (Kisumu, Kenya). The Supplementary Information Appendix contains the details of the model and its parameterization. The model stratifies the population into compartments according to vaccination status (vaccinated or unvaccinated), sexual risk group, and stage of HSV-2 infection using eight coupled nonlinear ordinary differential equations for each risk group of the four risk groups in the model. HSV-2 pathogenesis is represented by three stages: primary, latent (no shedding), and reactivated (shedding) stages. HSV-2 is of a chronic nature, therefore the latent and reactivated stages cycle through the entire life of the infected. The shedding frequency is assumed to be at 14% of each cycle [31]. The baseline transition rates of progression from primary to latent, latent to reactivated, and reactivated to latent are derived from the duration of each stage and the shedding frequency and they are 18.3, 4.7, and 28.6 per year, respectively. Baseline transmission probabilities per coital act per HSV-2 primary, latent, and reactivated stages are 0.01, 0.00, and 0.01, respectively[19]. We considered three possible efficacies for a prophylactic HSV-2 vaccine [23]: reducing susceptibility to infection (VES), and for those who get infected after the time of vaccination, reducing infectivity during shedding episodes (VEI) and reducing frequency of viral shedding (VEP) (Table 1 and Supplementary Information Appendix).

Table 1.

Prophylactic-vaccine efficacies expected to be an output of vaccine randomized controlled trials [1, 2].

| Vaccine efficacy | Definition |

|---|---|

| VES | Vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility: the relative reduction in risk of acquisition due to vaccination is given by 1 − VES |

| VEP | Vaccine efficacy of reducing shedding frequency: the relative reduction in the shedding frequency (given infection) due to prophylactic vaccination is given by 1 − VEP |

| VEI | Vaccine efficacy of reducing infectivity during shedding episodes: the relative reduction in transmission probability per discordant partnership due to prophylactically vaccinating the index partner (given his/her infection and shedding) is given by 1 − VEI |

Stanberry, LR (2004) Clinical trials of prophylactic and therapeutic herpes simplex virus vaccines. Herpes 11 Suppl 3: 161A–169A.

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00057330 (2009) HerpeVac Trial for Young Women.

We quantified the effect that variability in VES, VEI, or VEP would have on three summary measures (Appendix): basic reproduction number in a partially vaccinated population (R0V), vaccine utility (Φ), and vaccinee infection fitness (Ψ). Summary measure R0V quantifies the disease transmission sustainability in the partially vaccinated population such that when R0V <1 the vaccine would diminish HSV-2 chains of transmission in the general population. Summary measure Φ quantifies the utility of the vaccine through relative reduction in the basic reproduction number due to vaccination and reductions in prevalence and incidence [32, 33] such that when Φ > 0 equilibrium values of prevalence, incidence (absolute number of incident infections per year), and incidence rate (number of incident infections per susceptible individual per year) are reduced from their respective values without vaccination. Finally, vaccinee infection fitness (Ψ) is a measure of the heterogeneity in transmission introduced by vaccination [33] such that when Ψ is considerably below one (Ψ < 1), many fewer secondary infections are caused by the infected and vaccinated compared to infected and unvaccinated populations.

Our summary measures are appropriate tools for estimating the long-term effect of a partially efficacious vaccine. To derive each summary measure analytically, we simplified our mathematical model for a population with uniform risk behavior. In the quantitative predictions presented below, for each vaccine efficacy scenario, we assumed universal adolescent vaccination (f =100%). Although it has never been proven that risk behavior compensation could accompany HSV-2 vaccination, for completeness we assumed a modest risk behavior compensation of r =10% for those vaccinated relative to baseline risk behavior. Other assumptions included a uniform average sexual-risk of two partners per year, and life-long protection upon vaccination.

To measure the short-term impact of a vaccine in a high prevalence region, we next presented a more detailed mathematical model that included heterogeneous risk behavior. This version of the model was fitted to Kisumu’s prevalence data. We chose the parameter values of the model according to the best available empirical evidence of the biology and epidemiology of HSV-2 infection. In particular, recently established detailed empirical data about the pattern of HSV-2 reactivation in its clinical and subclinical form [34], played a central role in our assumptions. The behavioral parameters in the model are informed by the measurements of the Four City study [35–37]. The model’s assumptions are listed in Table 2 along with their references.

Table 2.

Summary of the parameters used in the model.

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| HSV-2 transmission probability per coital act per HSV-2 stage | ||

| Primary infection (pIS(1, j)→S(i)) | 0.011 | [3] |

| Latency (pIS(2, j)→S(i)) | 0 | (assumption) |

| Reactivation (pIS(3, j)→S(i)) | 0.01 | [3] |

| HSV-2 shedding frequency (ξ) | 14% of the time | [4] |

| HSV-2 transition rates between stages (absence of vaccination) | ||

| From primary to latent infection (π1) | 18.3 per year | (derived) |

| From latent infection to reactivation (π2) | 4.7 per year | (derived) |

| From reactivation to latent infection (π3) | 28.6 per year | (derived) |

| Behavioral and demographic data for Kisumu, Kenya | ||

| Frequency of coital acts per HSV-2 stage: | ||

| Primary stage (n1) | 10.6 per month | [5] |

| Latent stage (n2) | 11.0 per month | [5] |

| Reactivation stage (n3) | 7.1 per month | [5] |

| Duration of sexual partnerships: | ||

| Low risk with low risk (dIS(α,1)→S(1)) | 48 months | (representative value) |

| Low risk with low to intermediate risk (dIS(α,1)→S(2)) = (dIS(α,2)→S(1)) | 36 months | (representative value) |

| Low risk with intermediate to high risk (dIS(α,1)→S(3)) = (dIS(α,3)→S(1)) | 24 months | (representative value) |

| Low risk with high risk (dIS(α,1)→S(4)) = (dIS(α,4)→S(1)) | 12 months | (representative value |

| Low to intermediate risk with low to intermediate risk (dIS(α,2)→S(2)) | 24 months | (representative value) |

| Low to intermediate risk with intermediate to high risk (dIS(α,2)→S(3)) = (dIS(α,3)→S(2)) | 12 months | (representative value) |

| Low to intermediate risk with high risk (dIS(α,2)→S(4)) = (dIS(α,4)→S(2)) | 6 months | (representative value) |

| Intermediate to high risk with intermediate to high risk (dIS(α,3)→S(3)) | 6 months | (representative value) |

| Intermediate to high risk with high risk (dIS(α,3)→S(4)) = (dIS(α,4)→S(3)) | 1 month | (representative value) |

| High risk with high risk (dIS(α,4)→S(4)) | 1 week | [6] |

| Fraction of the initial population size in each risk group ( ): | ||

| Low risk | 62.8% | [7] |

| Low to intermediate risk | 22.9% | [7] |

| Intermediate to high risk | 11.8% | [7] |

| High risk | 1.3% | [6] |

| Effective new sexual partner acquisition rate: | ||

| Low risk (ρS(1)) | 0.18 partners per year | (representative value calibrated to the epidemic) |

| Low to intermediate risk (ρS(2)) | 1.85 partners per year | (representative value calibrated to the epidemic) |

| Intermediate to high risk ((ρS(3))) | 8.2 partners per year | (representative value calibrated to the epidemic) |

| High risk ((ρS(3))) | 95 partners per year | (representative value calibrated to the epidemic) |

| Degree of assortativeness (e) | 0.2 | (representative value) |

| Duration of the sexual lifespan ( ) | 35 years | [8, 9] |

Prospective partner studies predict a value of 0.0005 [1] while time to HSV-2 studies estimate it at 0.022 [2]. Three independent rough estimates presented in [3] give 0.01.

Wald, A, Langenberg, AG, Link, K, et al. (2001) Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 from men to women. Jama 285: 3100–3106.

Wald, A, Krantz, E, Selke, S, et al. (2006) Knowledge of partners’ genital herpes protects against herpes simplex virus type 2 acquisition. J Infect Dis 194: 42–52.

Abu-Raddad, LJ, Magaret, AS, Celum, C, et al. (2008) Genital herpes has played a more important role than any other sexually transmitted infection in driving HIV prevalence in Africa. PLoS ONE 3: e2230.

Stamm, WE, Handsfield, HH, Rompalo, AM, et al. (1988) The association between genital ulcer disease and acquisition of HIV infection in homosexual men. Jama 260: 1429–1433.

Wawer, MJ, Gray, RH, Sewankambo, NK, et al. (2005) Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis 191: 1403–1409.

Morison, L, Weiss, HA, Buve, A, et al. (2001) Commercial sex and the spread of HIV in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 15 Suppl 4: S61–69.

Ferry, B, Carael, M, Buve, A, et al. (2001) Comparison of key parameters of sexual behaviour in four African urban populations with different levels of HIV infection. AIDS 15 Suppl 4: S41–50.

Abu-Raddad, LJ, Patnaik, P and Kublin, JG (2006) Dual infection with HIV and malaria fuels the spread of both diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Science 314: 1603–1606.

Buvé, A, Carael, M, Hayes, RJ, et al. (2001) Multicentre study on factors determining differences in rate of spread of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: methods and prevalence of HIV infection. AIDS 15 Suppl 4: S5–14.

Although there are substantial variations in the rate and pattern of HSV-2 reactivations [34, 38, 39], the critical parameter is the shedding frequency irrespective of whether the pattern is that of short but frequent reactivations or long but less frequent ones [19]; because by assumption the infectious state is manifested by shedding the virus and irrespective of the pattern of shedding. The assumption that all shedding is associated with possible transmission has not been validated, however. It is possible that only shedding above a certain quantitative threshold (such as 1000 HSV copies DNA/mL) commonly leads to transmission. A vaccine may also decrease infectivity of individual virions irrespective of their number due to increased immune surveillance in the genital tract. Vaccine efficacy of decreasing transmission during shedding VEI accounts for both of the above possibilities.

Results

Summary measures of vaccine impact at the population level

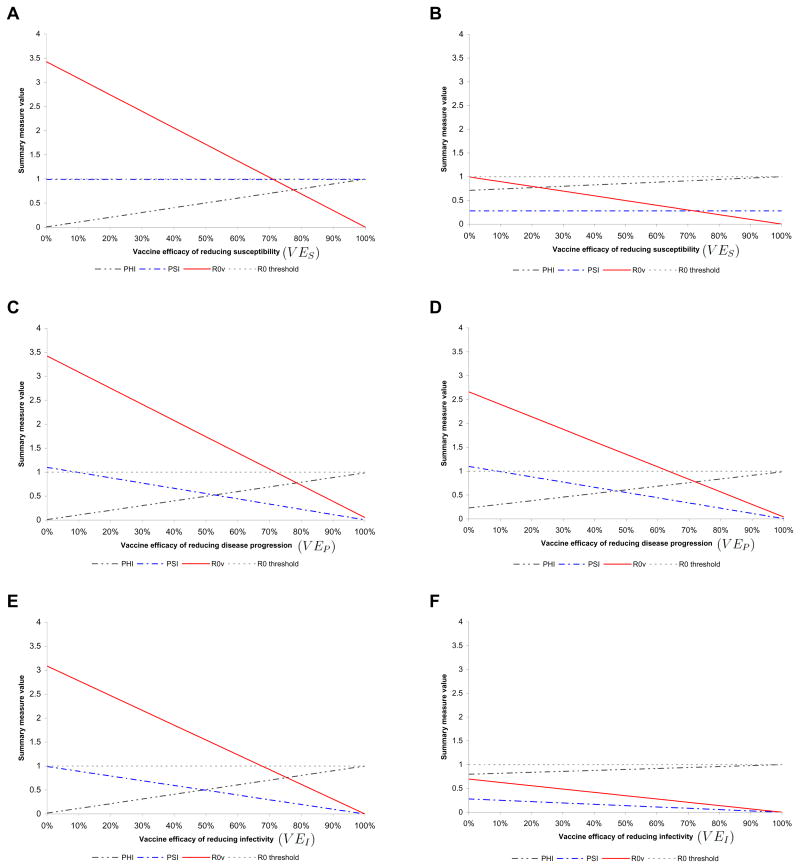

Increasing any of the vaccine efficacies of reducing susceptibility (VES), shedding frequency (VEP), or infectivity during shedding (VEI) from 0% to 100% produces steadily increasing positive vaccine utility (Φ) suggesting an increasingly beneficial vaccine at the population-level in terms of prevalence and incidence (Figure 1). Increasing any of the vaccine efficacies also produces steadily decreasing basic reproduction number with vaccination (R0V) suggesting more limited infection transmission and a decreasing fraction of the partially vaccinated population who can sustain the transmission of the disease. The vaccinee infection fitness (Ψ) does not depend on the vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility (VES), but decreases steadily with increasing the vaccine efficacies VEP or VEI. The steadily decreasing infection fitness manifests an increasing impact on the transmission dynamics of the disease by decreasing the number of secondary infections produced by infected and vaccinated individuals compared to infected and unvaccinated individuals in the partially vaccinated population.

Figure 1.

A set of mixed scenarios for the impact of HSV-2 vaccination. The vaccine utility (Φ), the vaccinee infection fitness (Ψ), and the basic reproduction number (R0V) for a scenario versus (A) vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility to HSV-2 (VES) at VEP =10% and VEI =0, (B) vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility to HSV-2 (VES) at VEP =75% and VEI =0, (C) vaccine efficacy of reducing shedding frequency (VEP) at VES =10% and VEI =0, (D) vaccine efficacy of reducing shedding frequency (VEP) at VES =30% and VEI =0, (E) vaccine efficacy of reducing infectivity (VEI) at VES =10% and VEP =10%, and (F) vaccine efficacy of reducing infectivity (VEI) at VES =30% and VEP =75%. In all these plots f =100% (fraction of adolescents vaccinated), r =10% (risk compensation), and the vaccine is assumed to have a lifelong immunity.

Figure 1 A displays that for a vaccine with a limited efficacy of reducing shedding frequency of VEP =10% and no efficacy in reducing infectivity i.e. VEI =0%, the basic reproduction number with vaccination (R0V) crosses the threshold of sustainability around a high value of the vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility of VES =75%. The vaccinee infection fitness remains flat at Ψ = 0.99 for all values of the vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility to HSV-2. These scenarios show that for a desirable population-level impact, an HSV-2 vaccine must reduce susceptibility by 75% if its effects on reducing shedding and infectivity during shedding in a vaccinated and infected host are limited.

However, as shown in Figure 1B, if VEI =0% as in Figure 1A, an increase in VEP to 75% renders the vaccine more beneficial at much smaller values of VES. The vaccinee fitness drops to 0.28 due to the higher VEP and the basic reproduction number with vaccination drops below sustainability threshold for all values of VES. These results suggest that one way to accomplish desirable population-level impact is to have a vaccine that reduces shedding frequency beyond 75% in addition to its protective effects against acquisition. The long-term benefits of such a vaccine are substantial even at low values of the vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility.

In contrast to Figure 1A and B, Figure 1C and D show how Ψ decreases steadily by increasing VEP at two different values of VES of 10% and 30%, respectively. The more optimistic scenario shown in Figure 1D with VES =30% and at VEP =75% predicts that the vaccine will be 8% more beneficial in terms of Φ than if the vaccine has only 10% efficacy of reducing susceptibility as in Figure 1C (Φ increases from 0.74 to 0.80). Also R0V drops from 0.89 to 0.70 suggesting less sustainable disease in the population. The population-level impacts at VES =10% and VEP =10%, and VES =30% and VEP =75%, can increase further if the vaccine also has non-negligible protection against infectivity (VEI) as shown in Figure 1E and F, respectively. It is notable that VEI must be very high (greater than 70%) if VES =10% and VEP =10% in order for the sustainability threshold to be crossed.

However, our predictions show that a vaccine with efficacy of reducing shedding frequency as high as 75% combined with efficacy of reducing susceptibility as low as 30% would be definitely and substantially beneficial in a population with an average of two sexual partners per year. Even though such an imperfect vaccine would not stop new HSV-2 infections among the vaccinated because of its low efficacy of reducing susceptibility, it still would effectively impact the dynamics of disease transmission. Moreover, it would render the number of secondary infections produced by infected and vaccinated individuals to one-quarter of the number produced by those infected and unvaccinated. The moderate risk compensation assumed here at 10% will not undermine the utility of such vaccine.

Simulated intervention

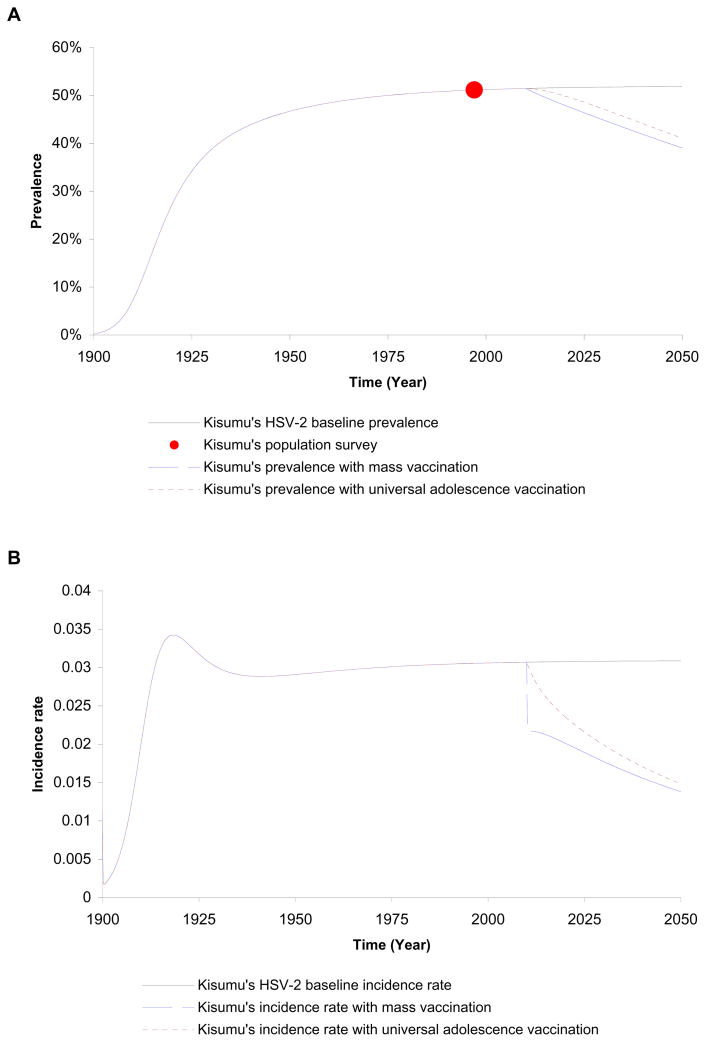

We next considered the epidemiology of intervention using vaccines in Kisumu, Kenya over a period of 10 years starting in 2010. We explored two schedules of vaccination: universal vaccination of adolescents as they enter sexual activity and mass vaccination of the sexually active population achieved within a year. We assumed vaccination using a vaccine with efficacy of reducing susceptibility to HSV-2 of VES =30%, efficacy of reducing HSV-2 shedding of VEP =75%, and no protection against infectivity i.e. VEI =0%. Furthermore, we assumed no risk compensation (r =0) as perception of risk to HSV-2 infection is probably not a strong determinant of risk behavior compared to HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. By the year 2020, the adolescent vaccination would reduce HSV-2 prevalence by 3%, HSV-2 incidence and incidence rate would decrease by 21% and 23%, respectively. A total of 3842 HSV-2 infections would be averted by 2020 in Kisumu (an adult population size of 200,000) using universal adolescent vaccination.

On the other hand, mass vaccination of all susceptible persons aged 15 to 49 by the year 2020 would reduce HSV-2 prevalence, incidence, and incidence rate by 7%, 30% and 35%, respectively. A total of 8430 HSV-2 infections would be averted by 2020 in Kisumu. Figure 2A and B displays how the impact of adolescent vaccination on prevalence and incidence rate would be less than mass vaccination and would take longer to accrue due to the delay time in achieving higher vaccination coverage. As shown in Figure 2A, although the impact of either schedule of vaccination on prevalence increases over time, the effect is initially modest. Equilibrium values of prevalence, incidence, and incidence rate would be achieved beyond year 2050 and would represent a percentage decrease of 69%, 69%, and 82%, with respect to baseline values, respectively. This delay is due to the lifelong nature of HSV-2 infection where the impact on prevalence will not be substantial until the already infected population ages and leaves the sexually active population. An additional cause of the delay is that the beneficial effects of VEP and VEI take longer to disseminate in a population compared to that of VES.

Figure 2.

Impacts of adolescence and mass vaccine interventions in Kisumu, Kenya administered in 2010 using a vaccine with efficacies of VES =30%, VEP =75%, and VEI =0. (A) Time series of prevalence values. The source of population survey data is the Four-City study [9] (B) Time series of incidence rate values.

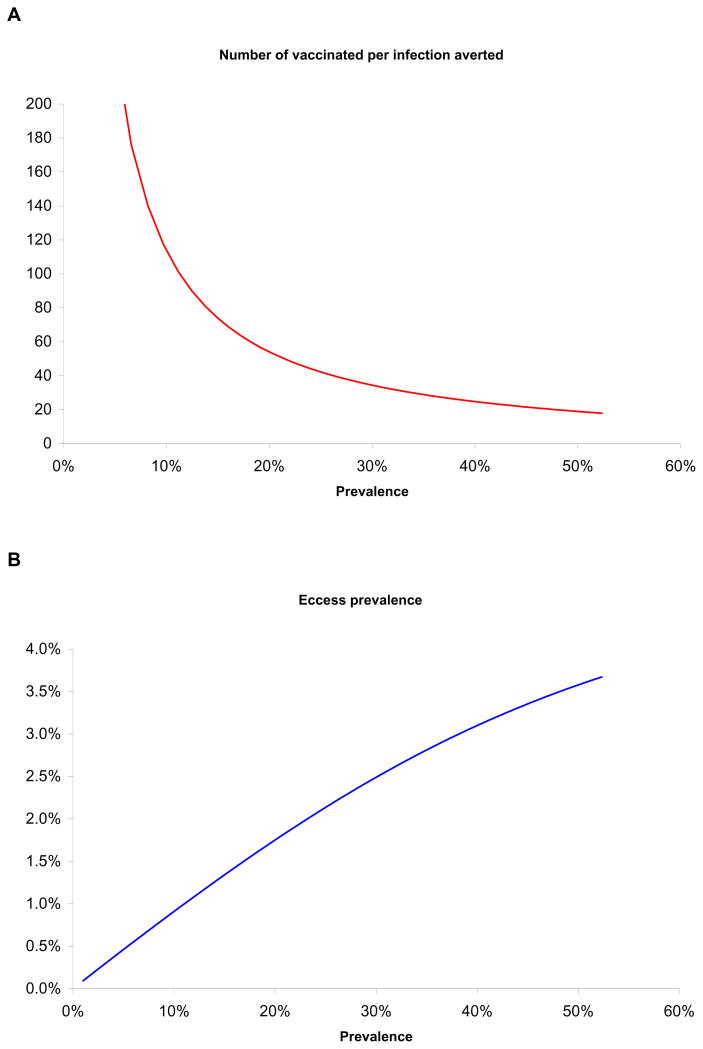

Furthermore, we investigated the ten-year impact of mass vaccination intervention in 2010 on HSV-2 excess prevalence (prevalence post-intervention subtracted from prevalence pre-intervention) and computed the number of vaccinated per infection averted in populations at various levels of total HSV-2 prevalence preserving the hierarchy of sexual risk of Kisumu’s settings (Figure 3). The excess prevalence is large when baseline prevalence in the absence of vaccination is high; the number of vaccinated per infection averted increases when HSV-2 prevalence in the absence of vaccination is lower. Eighteen vaccination procedures are needed per infection averted at high HSV-2 prevalence of 52%, projected for Kisumu, Kenya in 2010 which is representative of a large part of sub-Sharan Africa. This is compared to 64 vaccination procedures per infection averted for the United States at HSV-2 prevalence of 17%.

Figure 3.

Impact of mass vaccination in diverse HSV-2 settings having the same hierarchy of sexual risk as in Kisumu, Kenya. (A) Number of vaccination procedures needed per each HSV-2 infection averted at varying baseline HSV-2 prevalence levels before vaccine administration. (B) HSV-2 excess prevalence at endemic equilibrium (prevalence post-intervention subtracted from prevalence pre-intervention) at varying HSV-2 baseline prevalence levels. Vaccine properties are as in Figure 2.

We investigated the synergy between the vaccine efficacies of reducing shedding frequency and reducing susceptibility over time. The definition of synergy is delineated in the Supplementary Information Appendix. We found that (not shown) the effects of the two efficacies VES and VEP to be generally synergistic particularly in the long term. Larger value for either parameter leads to enhanced synergy. However in the short term, a slight redundancy between the two interventions is present while the transmission effects of VES accrue in the population. The impact of VEP in a population is substantial only after substantial number of people are vaccinated and subsequently infected with HSV-2.

Finally, we performed sensitivity and uncertainty analyses to assess the robustness and sensitivity of our short and long-term predictions to uncertainty in the vaccine efficacies, sexual behavior parameters and risk group structure, HSV-2 progression parameters and risk compensation behaviors (Supplementary Information Appendix). We found that our short–term predictions for the impact of vaccine intervention by 2020 in terms of excess prevalence, relative reduction in incidence, and excess incidence rate are largely invariable to the assumed variations in the vaccine efficacies of reducing infectivity and shedding frequency, or behavioral and HSV-2 progression parameters. However, the predicted excess prevalence and incidence rate as well as the reduction in incidence show substantial variability in the short-term to the assumed variation in the vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility. This is expected as in the short-term it is mainly VES that is driving the impact of the vaccine.

Over the long-term, substantial sensitivity in our predictions are observed with respect to the assumed variations in the vaccine efficacy of reducing shedding frequency and in the shedding frequency itself, respectively. The long-term sensitivity results attest to the role of VEP and shedding frequency in determining the course of HSV-2 transmission in presence of vaccination over a time horizon of few decades.

Discussion

Our approach enables prediction of the potential population impact of vaccines immediately after clinical trial results are available. In the case of HSV-2, a vaccine candidate’s efficacy measures are likely to become available after a clinical trial: vaccine efficacy of reducing susceptibility (VES) is often the primary outcome measure of most vaccine trials; but because current HSV-2 strategies also target reduction in shedding [26, 28], it is now standard practice to measure the effect of all HSV-2 interventions on shedding frequency and therefore a detailed assessment of vaccine efficacy of reducing shedding frequency (VEP) will be available as well; any effect on transmissibility during shedding as measured by VEI will be more difficult to obtain because a quantitative virologic threshold for HSV-2 transmission is not currently known. Nevertheless, if it is assumed that VEI is low as in our Kisumu simulations, then the other two measures can represent a worse case scenario for a vaccine’s effect in a population.

Our results underscore the relative impact of each of the vaccine efficacies at the population level, which is an important aspect of studying any imperfect vaccine. While the impact of VES at the population-level is immediate, the effects of VEP and VEI accrue over time. When VES is large, a small number of infections occur among vaccinees in the short term leaving little room for VEP to impact HSV-2 infectious spread. However in the long term there is a synergy between the effects of the two efficacies and they compliment each other.

Our study has several limitations. First, it does not address heterogeneity in shedding frequency in the general population. Ranges of shedding frequency among HSV-2 infected persons are from 0% – 78% [40]. In addition, there is evidence that frequent shedders may serve as “super spreaders” irrespective of sexual risk behavior [41]. Therefore, the effect of high VEP in this group would decrease the absolute amount of shedding more substantially than in infrequent shedding groups. Future mathematical models of vaccine efficacy would benefit from independent stratification of sexual risk behavior and shedding frequency into sub-groups. In addition, a true quantitative surrogate measure for transmission risk has not been identified as of yet. We account for the possibility that low-copy shedding may not be associated with transmission risk in our sensitivity analysis where we decrease shedding frequency, and also by incorporating VEI, which is a measure of vaccine efficacy regarding infectivity during shedding only. Lastly our model does not incorporate age-dependent targeting of interventions nor does it allow for differences by sex in transmission probability per coital act.

In summary, if HSV-2 vaccines that are currently under development have limited efficacy against HSV-2 acquisition, but have substantial efficacy of reducing shedding frequency or infectivity, then such vaccines are likely to have a high impact on HSV-2 incidence and prevalence over several decades, and will have a more immediate strong effect on HSV-2 incidence, particularly in high prevalence populations. Conversely, a vaccine that has a modest effect on acquisition but no effect on viral shedding is unlikely to be as effective. It is therefore imperative, that all future vaccine studies evaluate the effect that a vaccine has on genital viral shedding.

Summary.

Mathematical modeling is used to derive summary measures for the utility of HSV-2 vaccination and to assess the epidemiological impact of vaccination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RA and LJA are grateful for the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center for supporting this work. LJA is grateful for the Qatar National Research Fund for supporting this work.

Appendix

HSV-2 basic reproductive number without vaccination

The HSV-2 basic reproduction number (R0) for a population with no vaccination (f =0) is given by

| (A.1) |

where ti is the transmission probabilities per partnership from HSV-2 infected individuals in HSV-2 stage i to susceptible individuals. The parameters ρ, L, τ1, ξ, and χ are the effective partnership acquisition rate of unvaccinated individual, the average sexual life span, the average duration of HSV-2 primary infection, average shedding frequency among infected individuals, and the average frequency of latency and reactivation cycles, respectively.

HSV-2 basic reproductive number with adolescent vaccination

The HSV-2 basic reproduction number in a partially vaccinated population (R0V) is given by

| (A.2) |

where VES, VEP, and VEI are the vaccine efficacy of reducing: susceptibility, shedding frequency, and infectivity during shedding, respectively. The parameters f, r, and T are the fraction of adolescents entering sexual activity who are being vaccinated, their relative increase in risk behavior after vaccination, and the average duration of vaccine protection, respectively.

Vaccine utility

The vaccine utility (Φ) is defined by relative reduction in the basic reproduction number due to vaccination [32]: and is given by:

| (A.3) |

Vaccinee infection fitness

The vaccinee infection fitness (Ψ) is equal to the ratio of the number of secondary infections caused by an infected vaccinated individual (RIV) to the number of secondary infections caused by an infected unvaccinated individual (RIS) in a partially vaccinated and infection-free population (Supplementary Information Appendix): and is given by

| (A.4) |

Vaccine utility states and desirable values of summary measures

Vaccine utility was classified to definitely beneficial (deduced by Φ > 0 [33]) if it reduces endemic equilibrium values for prevalence, incidence (absolute number of incident infection per year), and incidence rate (number of incident infections per susceptible individual per year) compared to values without vaccination. The vaccine is considered partially beneficial (Φ =0) if at least one but not all of these values were reduced upon achieving equilibrium after vaccination and perverse (Φ <0) if none of these equilibrium values were reduced after vaccination. It is desirable for vaccines to have Φ >0, Ψ <1, and R0V <1.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information Appendix: Technical details of model description and sensitivity analysis.

References

- 1.Obasi A, Mosha F, Quigley M, et al. Antibody to herpes simplex virus type 2 as a marker of sexual risk behavior in rural Tanzania. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:16–24. doi: 10.1086/314555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wagner HU, Van Dyck E, Roggen E, et al. Seroprevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in a rural Ugandan population. Int J STD AIDS. 1994;5:332–337. doi: 10.1177/095646249400500509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamali A, Nunn AJ, Mulder DW, et al. Seroprevalence and incidence of genital ulcer infections in a rural Ugandan population. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:98–102. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gwanzura L, McFarland W, Alexander D, et al. Association between human immunodeficiency virus and herpes simplex virus type 2 seropositivity among male factory workers in Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:481–484. doi: 10.1086/517381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakwar J, Lavreys L, Thompson ML, et al. Cofactors for the acquisition of HIV-1 among heterosexual men: prospective cohort study of trucking company workers in Kenya. Aids. 1999;13:607–614. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langeland N, Haarr L, Mhalu F. Prevalence of HSV-2 antibodies among STD clinic patients in Tanzania. Int J STD AIDS. 1998;9:104–107. doi: 10.1258/0956462981921765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dada AJ, Ajayi AO, Diamondstone L, et al. A serosurvey of Haemophilus ducreyi, syphilis, and herpes simplex virus type 2 and their association with human immunodeficiency virus among female sex workers in Lagos, Nigeria. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:237–242. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199805000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CY, Ballard RC, Beck-Sague CM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and genital ulcer disease in South Africa: the herpetic connection. Sex Transm Dis. 2000;27:21–29. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buvé A, Carael M, Hayes RJ, et al. Multicentre study on factors determining differences in rate of spread of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: methods and prevalence of HIV infection. Aids. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S5–14. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slomka MJ, Ashley RL, Cowan FM, et al. Monoclonal antibody blocking tests for the detection of HSV-1- and HSV-2-specific humoral responses: comparison with western blot assay. J Virol Methods. 1995;55:27–35. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00042-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss H. Epidemiology of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in the developing world. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 1):24A–35A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celum C, Levine R, Weaver M, et al. Genital herpes and human immunodeficiency virus: double trouble. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:447–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Looker KJ, Garnett GP, Schmid GP. An estimate of the global prevalence and incidence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:805–812. A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.046128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, et al. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Aids. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wald A, Link K. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in herpes simplex virus type 2-seropositive persons: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:45–52. doi: 10.1086/338231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn JR, Biraro S, Weiss HA. Herpes simplex virus type 2: a key role in HIV incidence. Aids. 2009;23:1595–1598. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832e15e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Brookmeyer R, et al. Probability of HIV-1 transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV-1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 2001;357:1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Latif AS, Katzenstein DA, Bassett MT, et al. Genital ulcers and transmission of HIV among couples in Zimbabwe. Aids. 1989;3:519–523. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198908000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Raddad LJ, Magaret AS, Celum C, et al. Genital herpes has played a more important role than any other sexually transmitted infection in driving HIV prevalence in Africa. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, et al. Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1560–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Celum C, Wald A, Hughes J, et al. Effect of aciclovir on HIV-1 acquisition in herpes simplex virus 2 seropositive women and men who have sex with men: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:2109–2119. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hagerty C, Guiden M. Health Sciences/University of Washington Medicine news and community relations. Seattle, Washington, USA: 2009. Herpes medication does not reduce risk of HIV transmission from individuals with HIV and genital herpes but demonstrates modest reduction in HIV disease progression and leads to new important insights about HIV transmission, UW-led international study finds. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halloran ME, Struchiner CJ, Longini IM., Jr Study designs for evaluating different efficacy and effectiveness aspects of vaccines. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:789–803. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corey L, Langenberg AG, Ashley R, et al. Recombinant glycoprotein vaccine for the prevention of genital HSV-2 infection: two randomized controlled trials. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. Jama. 1999;282:331–340. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanberry LR, Spruance SL, Cunningham AL, et al. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1652–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanberry LR. Clinical trials of prophylactic and therapeutic herpes simplex virus vaccines. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 3):161A–169A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cattamanchi A, Posavad CM, Wald A, et al. Phase I study of a herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) DNA vaccine administered to healthy, HSV-2-seronegative adults by a needle-free injection system. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1638–1643. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00167-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.HerpeVac Trial for Young Women 2009 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00057330.

- 29.Blower S. Modelling the genital herpes epidemic. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 3):138A–146A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz EJ, Blower S. Predicting the potential individual- and population-level effects of imperfect herpes simplex virus type 2 vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1734–1746. doi: 10.1086/429299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stamm WE, Handsfield HH, Rompalo AM, et al. The association between genital ulcer disease and acquisition of HIV infection in homosexual men. Jama. 1988;260:1429–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLean AR, Blower SM. Imperfect vaccines and herd immunity to HIV. Proc Biol Sci. 1993;253:9–13. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abu-Raddad LJ, Boily MC, Self S, et al. Analytic insights into the population level impact of imperfect prophylactic HIV vaccines. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:454–467. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180959a94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mark KE, Corey L, Meng TC, et al. Topical resiquimod 0.01% gel decreases herpes simplex virus type 2 genital shedding: a randomized, controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1324–1331. doi: 10.1086/513276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferry B, Carael M, Buvé A, et al. Comparison of key parameters of sexual behaviour in four African urban populations with different levels of HIV infection. Aids. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S41–50. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagarde E, Auvert B, Carael M, et al. Concurrent sexual partnerships and HIV prevalence in five urban communities of sub-Saharan Africa. Aids. 2001;15:877–884. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morison L, Weiss HA, Buvé A, et al. Commercial sex and the spread of HIV in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. Aids. 2001;15(Suppl 4):S61–69. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mark KE, Wald A, Magaret AS, et al. Rapidly cleared episodes of herpes simplex virus reactivation in immunocompetent adults. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1141–1149. doi: 10.1086/591913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benedetti J, Corey L, Ashley R. Recurrence rates in genital herpes after symptomatic first-episode infection. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:847–854. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-11-199412010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wald A, Corey L, Cone R, et al. Frequent genital herpes simplex virus 2 shedding in immunocompetent women. Effect of acyclovir treatment. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1092–1097. doi: 10.1172/JCI119237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blower S, Wald A, Gershengorn H, et al. Targeting virological core groups: a new paradigm for controlling herpes simplex virus type 2 epidemics. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1610–1617. doi: 10.1086/424850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wald A, Langenberg AG, Link K, et al. Effect of condoms on reducing the transmission of herpes simplex virus type 2 from men to women. Jama. 2001;285:3100–3106. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wald A, Krantz E, Selke S, et al. Knowledge of partners’ genital herpes protects against herpes simplex virus type 2 acquisition. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:42–52. doi: 10.1086/504717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abu-Raddad LJ, Patnaik P, Kublin JG. Dual infection with HIV and malaria fuels the spread of both diseases in sub-Saharan Africa. Science. 2006;314:1603–1606. doi: 10.1126/science.1132338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.