Abstract

AIM: To gain molecular insights into the action of the histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACI) trichostatin-A (TSA) in pancreatic cancer (PC) cells.

METHODS: Three PC cell lines, BxPC-3, AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1, were treated with various concentrations of TSA for defined periods of time. DNA synthesis was assessed by measuring the incorporation of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine. Gene expression at the level of mRNA was quantified by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Expression and phosphorylation of proteins was monitored by immunoblotting, applying an infrared imaging technology. To study the role of p38 MAP kinase, the specific enzyme inhibitor SB202190 and an inactive control substance, SB202474, were employed.

RESULTS: TSA most efficiently inhibited BrdU incorporation in BxPC-3 cells, while CAPAN-1 cells displayed the lowest and AsPC-1 cells an intermediate sensitivity. The biological response of the cell lines correlated with the increase of histone H3 acetylation after TSA application. In BxPC-3 cells (which are wild-type for KRAS), TSA strongly inhibited phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 and AKT. In contrast, activities of ERK and AKT in AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1 cells (both expressing oncogenic KRAS) were not or were only modestly affected by TSA treatment. In all three cell lines, but most pronounced in BxPC-3 cells, TSA exposure induced an activation of the MAP kinase p38. Inhibition of p38 by SB202190 slightly but significantly diminished the antiproliferative effect of TSA in BxPC-3 cells. Interestingly, only BxPC-3 cells responded to TSA treatment by a significant increase of the mRNA levels of bax, a pro-apoptotic member of the BCL gene family. Finally, in BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cells, but not in the cell line CAPAN-1, significantly higher levels of the cell cycle inhibitor protein p21Waf1 were observed after TSA application.

CONCLUSION: The biological effect of TSA in PC cells correlates with the increase of acetyl-H3, p21Waf1, phospho-p38 and bax levels, and the decrease of phospho-ERK 1/2 and phospho-AKT.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Histone deacetylase inhibitor, Trichostatin-A, KRAS, MAP kinases, p21Waf1, AKT

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer (PC) constitutes the fourth to fifth leading cause of cancer deaths in Western countries. Despite many scientific efforts in recent years, PC still has the worst survival rate (< 5%) of all common human tumors[1,2], and therapeutic progress has been very slow. Important reasons for this dissatisfying situation include the lack of markers for early diagnosis, and the limited efficiency of radio- and chemotherapy.

In the development of ductal adenocarcinoma, the most common form of PC, accumulation of somatic gene mutations in pancreatic progenitor cells plays a key role[3]. For example, oncogenic mutations of the KRAS gene are detectable in approximately 90% of pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Other frequent genetic alterations in PC include loss or inactivation of the anti-oncogenes p53, p16/CDKN2A and DPC4[3].

While the essential contribution of somatic gene mutations is well established, recent studies have implicated epigenetic alterations in pancreatic carcinogenesis as well[4]. Thus, several genes with tumor suppressor properties, such as p16/CDKN2A (if not genetically inactivated)[5], p57KIP2/CDKN1C[6] and BNIP3[7], were shown to frequently undergo epigenetic promoter silencing by aberrant methylation of CpG islands. Hypomethylation of CpG’s, in contrast, has been described for several genes overexpressed in PC, including claudin4, S100A4, and prostate stem cell antigen[8].

Besides promoter methylation, histone modification by acetylation and further post-translational modifications represents a key principle of epigenetic regulation. Histone acetylation is associated with a repressed chromatin state, and tightly controlled by two classes of enzymes, histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases[9-11]. Inhibitors of histone deacetylases (HDACI) display anti-cancer activities and are, therefore, of growing clinical interest[12]. With respect to PC, recent experimental studies have suggested that HDACI may efficiently inhibit growth and induce apoptosis even of drug resistant cell lines[13-15]. Furthermore, a synergistic action with classic cytostatic drugs, such as gemcitabine, has been demonstrated[16-18]. We have recently shown that HDACI also exert antifibrotic efficiency by inhibiting functions of pancreatic stellate cells[19]. Since fibrosis is considered a progression factor of PC, this “side effect” might enhance antitumor activities of these drugs.

The molecular targets of HDACI in PC are incompletely characterized. Although expression of cell-cycle inhibitors (e.g. p21Waf1/CDKN1A[14,17]) and modulation of pro-apoptotic pathways[13,15,17] have been implicated in HDACI action, the molecular determinants of HDACI efficacy or ineffectiveness are currently unclear. Here, we have chosen three human PC cell lines that differ in their biological sensitivity to the HDACI trichostatin A (TSA) for a comparison of TSA effects at the molecular level. We have focussed on pathways that are considered to be important both for PC cell growth/survival as well as HDACI action. By this approach, we have identified molecular correlates of TSA effectiveness in PC cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Media and supplements for cell culture were obtained from Biochrom (Berlin, Germany), the 5-bromo-2'-deoxyuridine (BrdU) labelling and detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany), and SB202190 and SB202474 from Merck Chemicals/Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). TRI reagents and all chemicals used for reverse transcription and Taqman™ real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). PVDF membrane was supplied by Millipore (Schwalbach, Germany), anti-p21Waf1 immunoglobulin (mouse monoclonal) by Becton Dickinson Biosciences Pharmingen (Heidelberg, Germany), the other primary antibodies (all raised in rabbits) by New England BioLabs (Frankfurt, Germany), and Odyssey® blocking buffer, stripping buffer and secondary antibodies for immunoblotting by LI-COR (Bad Homburg, Germany). Tissue culture dishes (Corning plasticware), standard laboratory chemicals and TSA were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The HDACI was dissolved in ethanol and stored at -20°C as a stock solution (3.3 × 10-3 mol/L).

Cell culture

All cells used in this study represent human pancreatic carcinoma cell lines. CAPAN-1 cells were grown in IMDM supplemented with 17% foetal calf serum (FCS) and 10 mL/L non-essential amino acids (dilution of a 100 × stock solution). BxPC-3 cells were cultured in RPMI with 10% FCS. The culture medium for AsPC-1 cells was DMEM containing 10% FCS. All culture media were supplemented with 105 U/L penicillin and 100 mg/L streptomycin. The cell lines were grown at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. When reaching subconfluency, the cells were harvested by trypzination, and recultured according to the experimental requirements.

Quantification of DNA synthesis

DNA synthesis was assessed by measuring incorporation of BrdU into newly synthesized molecules. Therefore, PC cells growing in 96-well plates were pretreated with drugs as indicated. 24 h after drug application, BrdU labelling was initiated by adding labelling solution at a final concentration of 1 × 10-5 mol/L (in the culture medium). After an overnight incubation, labelling was stopped, and BrdU uptake was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunoblotting

Cells were harvested by medium aspiration and addition of boiling lysis buffer[20] directly to the cell monolayer. Cellular proteins received from equal numbers of cells were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10%-12% gels, depending on the experimental requirements) and transferred onto PVDF membrane by semi-dry blotting. After blotting, the filters were blocked and processed by incubation with the indicated primary antibody as previously described[20,21]. The secondary antibody was IRDye® 800CW conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG, respectively. All immunoblots were scanned at a wavelength of 800 nm, using an Odyssey® Infrared Imaging System. Signal intensities were quantified by means of the Odyssey® software version 3.0. Prior to reprobing with additional primary antibodies, the blots were treated with stripping buffer according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR using real-time TaqMan™ technology

The pancreatic cancer cell lines were challenged with TSA as indicated. Afterwards, total RNA was isolated with TRI reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA by means of TaqMan™ Reverse Transcription Reagents and random hexamer priming. Relative quantification of target cDNA levels by real-time PCR was performed in an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan™ Universal PCR Master Mix and the following Assay-on-Demand™ human gene-specific fluorescently labelled TaqMan™ MGB probes: Hs00180269_m1 (bax), Hs00355782_m1 (p21Waf1), and Hs99999905_m1 [glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), used as house-keeping control gene]. Following the guidelines of the manufacturer, PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 50 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C. The reactions were run at least in duplicate, and repeated 6 times with independent samples. Relative expression of each mRNA compared with GAPDH was calculated according to the equation ∆Ct = Cttarget - CtGAPDH. The relative amount of target mRNA in control cells and samples treated with drugs as indicated was expressed as 2-(∆∆Ct), where ∆∆Cttreatment = ∆Ctsample - ∆Ct control.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SE for the indicated number of separate cultures per experimental protocol. Statistical significance was analyzed using the indicated statistical test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

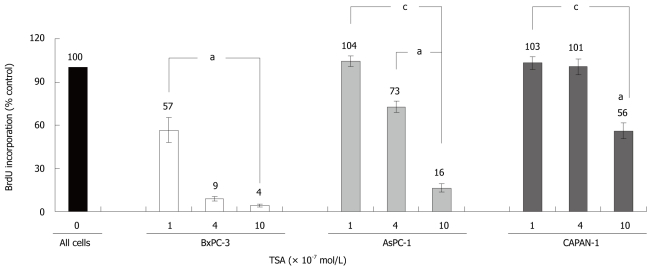

TSA enhances histone acetylation in PC cell lines

In initial experiments, we compared the effects of TSA on the acetylation of histone H3 in the three different pancreatic cancer cell lines used in this study (Figure 1). In all cell lines, a dose-dependent increase of H3 acetylation was observed, suggesting an inhibition of histone deacetylase activity. The effect of TSA was stronger in BxPC-3 cells than in the other two cell lines, and AsPC-1 cells were somewhat more sensitive to TSA treatment than CAPAN-1 cells. The functional consequences of TSA action were investigated in subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

Enhancement of histone H3 acetylation by trichostatin-A (TSA). The indicated pancreatic cancer (PC) cell lines were treated with various concentrations of TSA for 24 h. A: Histone H3 acetylation was analyzed by immunoblotting; B: Reprobing of the blot with an anti-H3 protein-specific antibody revealed no systematic differences of the histone H3 amount among the samples; C: Acetyl-histone H3 levels were further investigated using image analysis software and related to the histone H3 protein level. Therefore, acetyl-histone H3 and H3 protein signal intensities were determined, and the ratio acetyl-histone H3/H3 protein was calculated. A ratio of 100% corresponds to control cells cultured without TSA. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

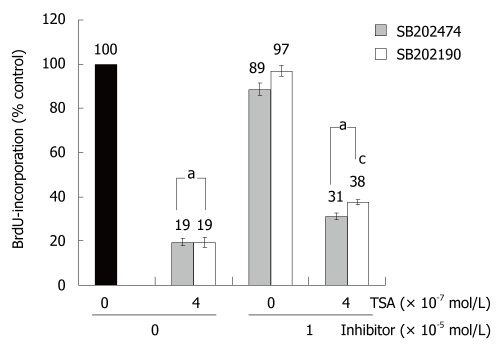

TSA inhibits DNA synthesis of pancreatic cancer cells

TSA significantly inhibited the incorporation of BrdU into newly synthesized DNA in all cell lines tested, but with remarkably different efficiency (Figure 2): While BxPC-3 cells showed a significant response at a TSA concentration of 1 × 10-7 mol/L, 10 times higher doses were required to reduce the DNA synthesis of CAPAN-1 cells. AsPC-1 cells displayed an intermediate sensitivity. Furthermore, at any concentration tested, BrdU incorporation was significantly stronger inhibited in BxPC-3 cells than in the other two cell lines. Action of HDACI has previously been linked to the suppression of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis[13-15], and diminished incorporation of BrdU might be an indicator of both. Although a differentiation between these processes was not our main focus, we noticed that at TSA concentrations up to 4 × 10-7 mol/L the rate of cell death did not increase in any cell line over a treatment period of 48 h (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of TSA on the BrdU incorporation of PC cell lines. BxPC-3, AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1 cells were treated with TSA as indicated for 24 h, before DNA synthesis was assessed with the BrdU incorporation assay. 100% BrdU incorporation corresponds to cells cultured without TSA. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 6 separate cultures); aP < 0.05 vs control cultures, cP < 0.05 vs BxPC-3 cells (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test).

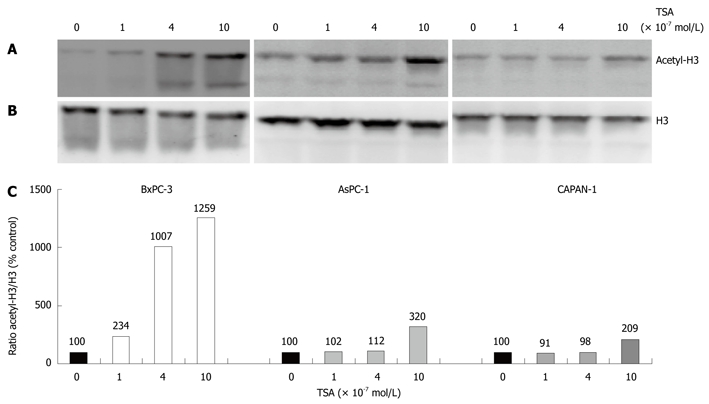

Effects of TSA at the level of signal transduction

In the next experiments, the molecular basis of the different TSA responsiveness of our PC cell lines was studied. Therefore, we chose the approach to focus on intracellular proteins that have previously been implicated both in HDACI action and stimulation/inhibition of PC cell growth. As shown in Figure 3, a cell line-specific pattern of the TSA response was observed.

Figure 3.

Expression and phosphorylation of signal transduction proteins in TSA-treated PC cell lines. BxPC-3, AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1 cells were treated with TSA at concentrations up to 10 × 10-7 mol/L for 24 h. A: Expression and phosphorylation of the indicated proteins was analyzed by immunoblotting. Phospho-proteins were detected first, followed by a reprobing of the blots with anti-protein specific antibodies. Actin was used as a housekeeping control protein; B-D: Fluorescence signal intensities of phospho (P) proteins and total proteins were quantified using Odyssey® software version 3.0. Subsequently, the ratios phospho-ERK/ERK protein (B), phospho-AKT/AKT protein (C) and phospho-p38/p38 protein (D) were determined. A ratio of 100% corresponds to control cells cultured without TSA. Data of 8 independent experiments were used to calculate mean values and SE; aP < 0.05 vs control cultures, cP < 0.05 vs BxPC-3 cells (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test).

In BxPC-3 cells, but not in the other two cell lines, treatment with TSA at 10 × 10-7 mol/L significantly diminished phosphorylation of the kinases ERK 1 and 2, which are key elements of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway[22] (Figure 3A, panel 1 and 2, and Figure 3B). Furthermore, only in BxPC-3 cells TSA at 10 × 10-7 mol/L almost completely blocked phosphorylation of AKT (Figure 3A, panel 3 and 4, and Figure 3C), which acts downstream of the phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase[23]. A further evaluation of the PI 3-kinase/AKT pathway revealed that its best-characterized negative regulator, the PI 3-kinase phosphatase PTEN[23], was expressed and phosphorylated in all three cell lines in a TSA-independent manner (Figure 3A, panel 5 and 6; quantification data not shown). These data suggest that PTEN was not involved in the mediation of TSA effects on AKT.

Finally, we studied how TSA treatment affected phosphorylation of the MAP kinase p38, which like ERK plays a profound role in tumorigenesis[24]. Here, in all three cell lines a dose-dependent enhancement of phosphorylation was observed (Figure 3A, panel 7 and 8, and Figure 3D). The effect was most pronounced in BxPC-3, followed by AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1 cells.

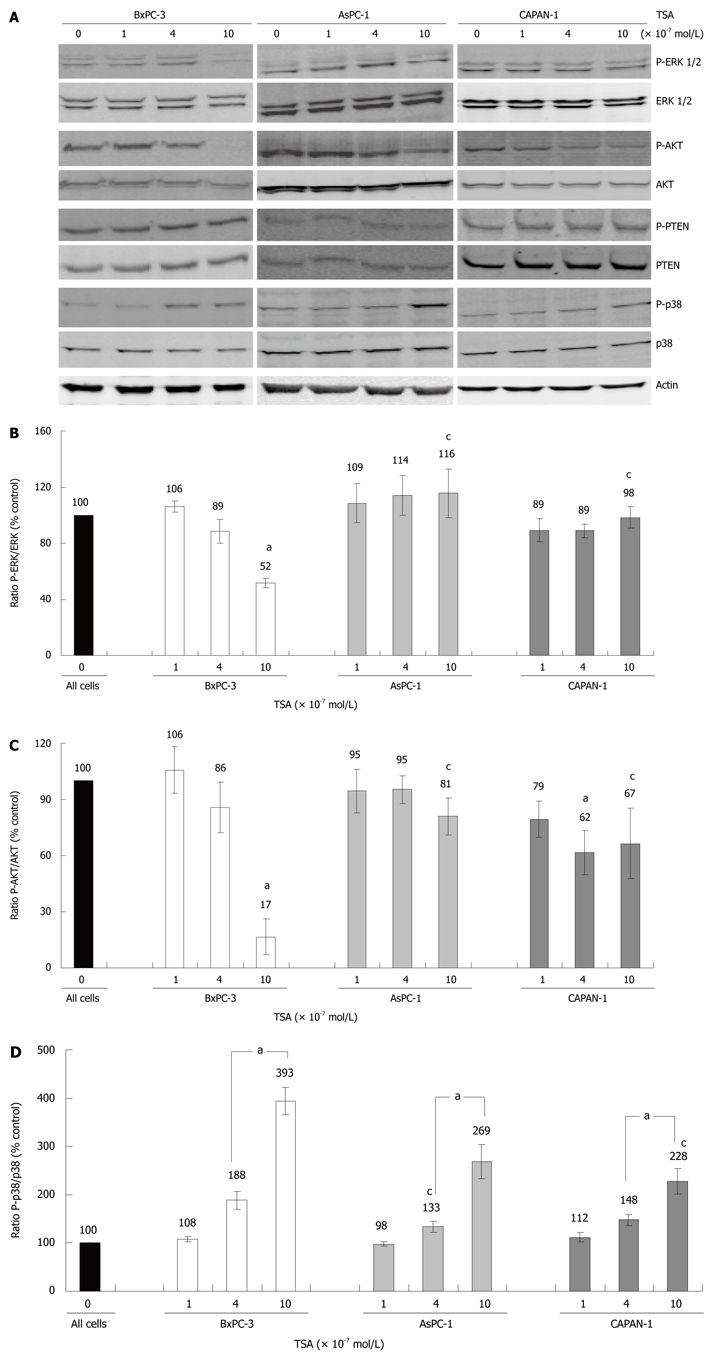

Effects of p38 MAP kinase inhibition on DNA synthesis of PC cells

To study the biological consequences of p38 MAP kinase activation by TSA, the specific inhibitor SB202190 and an inactive control substance, SB202474, were employed. In the absence of TSA, incubation of BxPC-3 cells with the drugs did not significantly affect BrdU incorporation. In the presence of TSA, BrdU incorporation of SB202190-treated BxPC-3 cells exceeded the one of cells exposed to SB202474 (Figure 4). Although the difference was small, it reached statistical significance. In AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1 cells, SB202190 had no effect on the incorporation of BrdU; independent of the presence or absence of TSA (data not shown). The data therefore suggest a (limited) contribution of p38 MAP kinase to the inhibition of DNA synthesis by TSA selectively in BxPC-3 cells; the cell line which had also shown the strongest TSA-dependent increase of p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation (Figure 3D).

Figure 4.

SB202190 diminished inhibition of BrdU incorporation by TSA in BxPC-3 cells. The cells were treated with TSA, SB202190 and SB202474 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h, before DNA synthesis was assessed with the BrdU incorporation assay. 100% BrdU incorporation corresponds to untreated cells. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 16 separate cultures); aP < 0.05 vs control cultures, cP < 0.05 vs SB202474-treated cells (identical concentration of TSA) (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test).

Expression of TSA target genes in PC cell lines

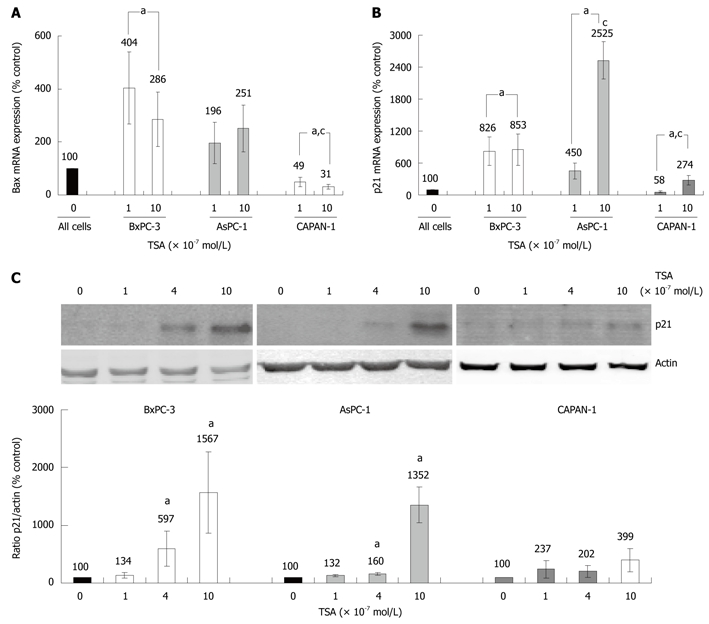

Various HDACI target genes identified so far have been linked to the induction of cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. We chose two of the best-studied candidate genes, BAX and p21Waf1 (CDKN1A, Cip1), to compare the effects of TSA on gene expression in the three PC cell lines. BAX, a pro-apoptotic member of the BCL gene family[25], and the cell-cycle inhibitor gene p21Waf1 were found to be expressed in all cell lines (Figure 5A and B). In TSA-treated BxPC-3 cells, a significant increase of bax mRNA levels was observed, whereas AsPC-1 cells displayed a non-significant tendency towards higher bax mRNA levels, only. Surprisingly, CAPAN-1 cells responded to TSA application by a dose-dependent, significant decrease of bax mRNA expression (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Effects of TSA on BAX and p21Waf1 expression in PC cell lines. A, B: The cell lines were incubated with TSA for 8 h as indicated. The mRNA expression of Bax (A), p21Waf1 (B) and the housekeeping gene GAPDH (A and B) was analyzed by real time PCR, and relative amounts of target mRNA were determined. 100% mRNA expression of each gene corresponds to cells cultured without TSA. Data of ≥ 6 independent experiments were used to calculate mean values and SE; aP < 0.05 vs control cultures, cP < 0.05 vs BxPC-3 cells (Mann-Whitney test); C: BxPC-3, AsPC-1 and CAPAN-1 cells were treated with TSA at concentrations up to 10 × 10-7 mol/L for 24 h. Expression of the p21Waf1 protein and actin (housekeeping control protein) was analyzed by immunoblotting. Fluorescence signal intensities of p21Waf1 and actin were quantified, and the ratio p21Waf1/actin was determined. A ratio of 100% corresponds to control cells cultured without TSA. Data of 8 independent experiments were used to calculate mean values and SE; aP < 0.05 vs control cultures, cP < 0.05 vs BxPC-3 cells (Wilcoxon’s rank sum test).

Treatment of BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cells with TSA caused a strong increase of p21Waf1 mRNA expression, while in CAPAN-1 cells this effect was less pronounced (Figure 5B). Similar results were obtained at the level of p21Waf1 protein expression (Figure 5C). Here, in CAPAN-1 cells the TSA effect did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

The molecular targets of HDACI in PC cells have been studied by several groups in recent years. The results suggest that inhibitors of cell-cycle progression, such as p21Waf1/CDKN1A, and regulators of cell survival/death are involved in the mediation of antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of HDACI[13-15,17]. The molecular basis of variations in the biological efficiency of HDACI in different PC cells, however, has not been systematically studied so far. It is also largely unknown how precisely the increase of histone acetylation is linked to the biological and molecular effects of HDACI described above. To address these questions, we chose an experimental model system of three PC cell lines that differ significantly in their biological responsiveness to the HDACI trichostatin A. BxPC-3 cells, which displayed the strongest increase of histone H3 acetylation and decrease of DNA synthesis, were the only wild-type KRAS cells in this study. Interestingly, only BxPC-3 cells also showed a significant inhibition of ERK 1/2 and AKT phosphorylation in response to TSA treatment. Both ERK 1/2 (through Raf-1 and MEK) and AKT (through PI 3-kinase) are downstream of KRAS[26]. We therefore hypothesize that oncogenic KRAS mutations may reduce, but not abolish, TSA efficiency by preventing an inhibition of AKT and ERK 1/2 signalling.

Although BxPC-3 cells were most sensitive to TSA treatment, DNA synthesis of CAPAN-1 and AsPC-1 cells could also be reduced by the drug. In CAPAN-1 cells, however, a significant effect was achieved at the high TSA concentration of 1 × 10-6 mol/L only. Searching for further molecular explanations of these phenomena, we found that CAPAN-1 cells showed the weakest increase of acetyl-histone H3, p21Waf1 and phospho-p38 levels. Furthermore, an unexpected decrease of bax mRNA expression was observed in these cells.

Taken together, our data suggest that the biological efficiency of TSA in the different PC cell lines correlates with the increase of histone H3 acetylation, p21Waf1 expression and p38 MAP kinase phosphorylation, and the decrease of ERK 1/2 and AKT phosphorylation. Using a specific inhibitor of p38, we also obtained evidence for a direct involvement of this kinase in the mediation of the antiproliferative effect of TSA in the cell line BxPC-3. Along these lines, the efficiency of TSA in PC cells might be restricted by antagonistic effects of other factors, such as oncogenic KRAS, on intracellular pathways that are critical for HDACI action.

Considering established crosstalks between growth-regulatory pathways, we hypothesize that the diverse molecular effects of TSA observed in this study are, at least in part, causally related. Specifically, we suggest direct links between modulation of MAP kinase (ERK, p38) signalling by the drug and induction of p21Waf1 expression, since activation of p38 and inhibition of ERK phosphorylation have previously been shown to enhance p21Waf1 promoter activation in other contexts[27-29]. Furthermore, AKT has been implicated in functional inactivation of p21Waf1 through the phosphorylation of the protein, resulting in its cytoplasmic localization[30]. While cellular localization of p21Waf1 was not investigated in this study, we observed an inverse correlation between p21Waf1 expression and AKT activity.

A detailed knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of TSA action is essential to understand what determines the HDACI sensitivity and resistance of tumors. Our data encourage further studies in the field of pancreatic cancer, where novel therapeutic approaches are particularly needed.

COMMENTS

Background

Pancreatic cancer has the worst prognosis of all common human tumors, indicating an urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches. Histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as trichostatin-A (TSA) or the clinically available drug SAHA, display anti-cancer activities in vitro and in vivo. They are therefore under experimental investigation for the treatment of different human malignancies. Histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACI) act as epigenetic regulators by increasing histone acetylation, which is associated with a repressed chromatin state.

Research frontiers

While the immediate targets of HDACI action are clear, the precise molecular links between histone protein acetylation and suppression of cancer cell growth remain to be established. In most types of cancer cells, inhibitors of cell cycle progression and regulators of cell survival/apoptosis are important mediators of HDACI effects. However, a systematic overview of the underlying molecular mechanisms is missing. Thus, it is currently unknown which genes and proteins critically determine the efficacy or ineffectiveness of HDACI in pancreatic cancer (PC) cells.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The results of this study provide molecular insights into HDACI action in pancreatic cancer cells. The data suggest that the biological efficiency of TSA in different PC cell lines, indicated by the inhibition of DNA synthesis, correlates with the increase of histone H3 acetylation, but also both with genetic alterations and specific effects at the level of intracellular signal transfer as well as gene expression. In detail, expression of wild-type KRAS, a strong increase of bax, p21Waf1 and phospho-p38 levels, and a diminished phosphorylation of ERK 1/2 and AKT were found to be associated with a high biological efficiency of the drug. The authors hypothesize that PC cells differ in their biological sensitivity to TSA, since not all tumor cells exhibit the full range of molecular targets required for an effective HDACI action.

Applications

The results of this study open an avenue for the further investigation of the molecular determinants of HDACI action in PC cells. An improved understanding of HDACI effects at the molecular level may ultimately lead to the establishment of markers predicting the HDACI sensitivity or resistance of tumors.

Terminology

Pancreatic cancer is a malignancy of the pancreas with poor prognosis that typically displays the histological features of a ductal adenocarcinoma. HDACI, including trichostatin A, are substances that increase histone acetylation by inhibiting the activity of histone deacetylases. MAP kinases (such as ERK 1/2 and p38), PTEN and AKT are intracellular proteins that are involved in the intracellular transfer of receptor-derived signals regulating e.g. cell growth and survival. p21Waf1 belongs to a family of proteins that prevent cells from entering the S-phase of the cell cycle, while bax is an inductor of apoptotic cell death.

Peer review

It is an interesting and well written manuscript, and a scientifically sound modest extension of what is known regarding histone deacetylase inhibitors and cancer.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Mrs. Helga Schulze and Mrs. Katja Bergmann.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Jorg Kleeff, MD, Consultant Surgeon, Department of Surgery, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University of Munich, Ismaninger Str. 22, 81675 Munich, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Ma WH

References

- 1.Eckel F, Schneider G, Schmid RM. Pancreatic cancer: a review of recent advances. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2006;15:1395–1410. doi: 10.1517/13543784.15.11.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider G, Siveke JT, Eckel F, Schmid RM. Pancreatic cancer: basic and clinical aspects. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1606–1625. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Real FX. A “catastrophic hypothesis” for pancreas cancer progression. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1958–1964. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00389-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omura N, Goggins M. Epigenetics and epigenetic alterations in pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:310–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schutte M, Hruban RH, Geradts J, Maynard R, Hilgers W, Rabindran SK, Moskaluk CA, Hahn SA, Schwarte-Waldhoff I, Schmiegel W, et al. Abrogation of the Rb/p16 tumor-suppressive pathway in virtually all pancreatic carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3126–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato N, Matsubayashi H, Abe T, Fukushima N, Goggins M. Epigenetic down-regulation of CDKN1C/p57KIP2 in pancreatic ductal neoplasms identified by gene expression profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4681–4688. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okami J, Simeone DM, Logsdon CD. Silencing of the hypoxia-inducible cell death protein BNIP3 in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5338–5346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato N, Maitra A, Fukushima N, van Heek NT, Matsubayashi H, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Rosty C, Goggins M. Frequent hypomethylation of multiple genes overexpressed in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4158–4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan AU, Krishnamurthy S. Histone modifications as key regulators of transcription. Front Biosci. 2005;10:866–872. doi: 10.2741/1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuks F. DNA methylation and histone modifications: teaming up to silence genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2005;15:490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Nuclear histone acetylases and deacetylases and transcriptional regulation: HATs off to HDACs. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;1:300–308. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang L. Targeting histone deacetylases for the treatment of cancer and inflammatory diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:611–616. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Morales P, Gómez-Martínez A, Carrato A, Martínez-Lacaci I, Barberá VM, Soto JL, Carrasco-García E, Menéndez-Gutierrez MP, Castro-Galache MD, Ferragut JA, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induced caspase-independent apoptosis in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1222–1230. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Faggioli L, Scupoli MT, Moore PS, Bassi C, Scarpa A, Palmieri M. Trichostatin A, an inhibitor of histone deacetylases, strongly suppresses growth of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Mol Carcinog. 2003;38:59–69. doi: 10.1002/mc.10145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore PS, Barbi S, Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Bassi C, Palmieri M, Scarpa A. Gene expression profiling after treatment with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A reveals altered expression of both pro- and anti-apoptotic genes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1693:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piacentini P, Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Moore PS, Palmieri M, Scarpa A. Trichostatin A enhances the response of chemotherapeutic agents in inhibiting pancreatic cancer cell proliferation. Virchows Arch. 2006;448:797–804. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gahr S, Ocker M, Ganslmayer M, Zopf S, Okamoto K, Hartl A, Leitner S, Hahn EG, Herold C. The combination of the histone-deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A and gemcitabine induces inhibition of proliferation and increased apoptosis in pancreatic carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donadelli M, Costanzo C, Beghelli S, Scupoli MT, Dandrea M, Bonora A, Piacentini P, Budillon A, Caraglia M, Scarpa A, et al. Synergistic inhibition of pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell growth by trichostatin A and gemcitabine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1095–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bülow R, Fitzner B, Sparmann G, Emmrich J, Liebe S, Jaster R. Antifibrogenic effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on pancreatic stellate cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rateitschak K, Karger A, Fitzner B, Lange F, Wolkenhauer O, Jaster R. Mathematical modelling of interferon-gamma signalling in pancreatic stellate cells reflects and predicts the dynamics of STAT1 pathway activity. Cell Signal. 2010;22:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jonitz A, Fitzner B, Jaster R. Molecular determinants of the profibrogenic effects of endothelin-1 in pancreatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4143–4149. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang L, Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang BH, Liu LZ. PI3K/PTEN signaling in angiogenesis and tumorigenesis. Adv Cancer Res. 2009;102:19–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(09)02002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:537–549. doi: 10.1038/nrc2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalier L, Cartron PF, Juin P, Nedelkina S, Manon S, Bechinger B, Vallette FM. Bax activation and mitochondrial insertion during apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:887–896. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giehl K. Oncogenic Ras in tumour progression and metastasis. Biol Chem. 2005;386:193–205. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee B, Kim CH, Moon SK. Honokiol causes the p21WAF1-mediated G(1)-phase arrest of the cell cycle through inducing p38 mitogen activated protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5177–5184. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moon SK, Choi YH, Kim CH, Choi WS. p38MAPK mediates benzyl isothiocyanate-induced p21WAF1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via the regulation of Sp1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;350:662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho PY, Hsu SP, Liang YC, Kuo ML, Ho YS, Lee WS. Inhibition of the ERK phosphorylation plays a role in terbinafine-induced p21 up-regulation and DNA synthesis inhibition in human vascular endothelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;229:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou BP, Liao Y, Xia W, Spohn B, Lee MH, Hung MC. Cytoplasmic localization of p21Cip1/WAF1 by Akt-induced phosphorylation in HER-2/neu-overexpressing cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:245–252. doi: 10.1038/35060032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]