Abstract

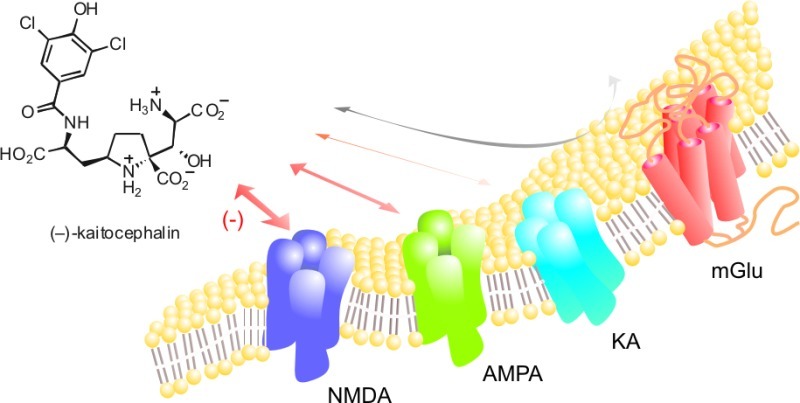

Kaitocephalin is the first discovered natural toxin with protective properties against excitotoxic death of cultured neurons induced by N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) or α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA)/kainic acid (kainate, KA) receptors. Nevertheless, the effects of kaitocephalin on the function of these receptors were unknown. In this work, we report some pharmacological properties of synthetic (−)-kaitocephalin on rat brain glutamate receptors expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes and on the homomeric AMPA-type GluR3 and KA-type GluR6 receptors. Kaitocephalin was found to be a more potent antagonist of NMDA receptors (IC50 = 75 ± 9 nM) than of AMPA receptors from cerebral cortex (IC50 = 242 ± 37 nM) and from homomeric GluR3 subunits (IC50 = 502 ± 55 nM). Moreover, kaitocephalin is a weak antagonist of the KA-type receptor GluR6 (IC50 ∼ 100 μM) and of metabotropic (IC50 > 100 μM) glutamate receptors expressed by rat brain mRNA.

Keywords: Glutamate receptors, kainate, AMPA, NMDA, kaitocephalin, Xenopus oocytes

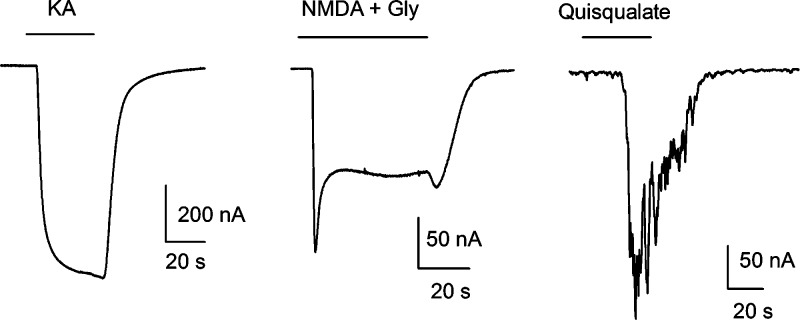

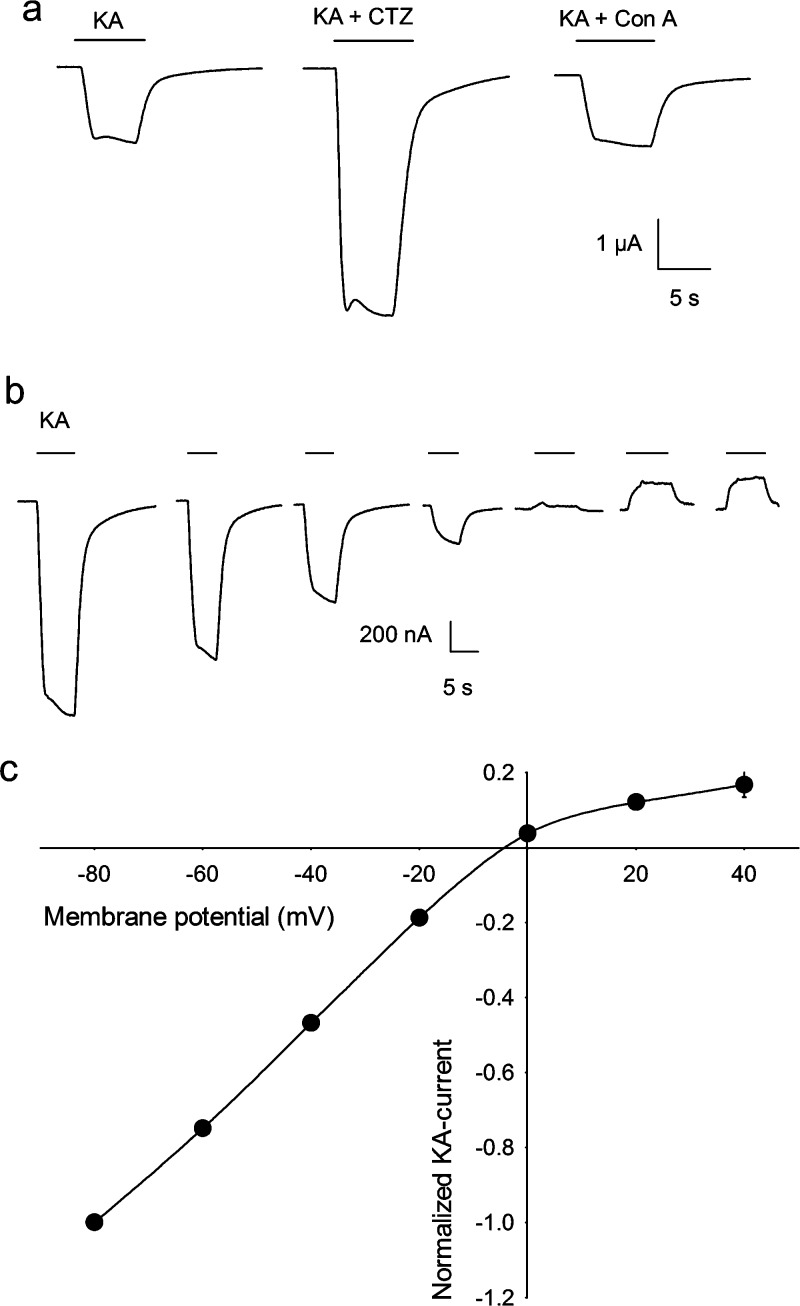

Neuronal membrane receptors activated by the amino acid l-glutamate are the main drivers of excitatory activity in the vertebrate nervous system. These receptors can form ligand-gated ion channels (ionotropic receptors; iGluRs) or can be linked to a second messenger receptor channel-coupling system (metabotropic receptors; mGluRs) (1). The iGluRs are tetrameric proteins that mediate fast synaptic transmission and are grouped into three classes, according to their differential affinity for the agonists N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), kainate (KA), and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) (2). The mGluRs belong to the G-protein-coupled receptor superfamily, contain a heptahelical domain in the membrane, and can be divided into three main groups according to their agonist pharmacology, primary sequence, and G-protein effector coupling (3). Group I contains the receptors mGluR1 and mGluR5, which activate phospholipase C (PLC). Groups II (mGluR2 and mGluR3) and III (mGluR4 and mGluR6−7) both inhibit adenylate cyclase (1). mGluRs modulate neurotransmitter release and the electrical and synaptic activity of neurons and glial cells (4). Because of the broad distribution and functions of glutamate receptors in the brain, it is not surprising that alterations in the activity of iGluRs or mGluRs disrupt many complex processes such as learning and memory (5,6); and in ischemic conditions, a common situation in the diseased brain, overactivation of iGluRs leads to neuronal degeneration and death by a mechanism known as excitotoxicity (7). Evidence that excitotoxicity is partly involved in the neuronal degeneration observed in epilepsy and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases has spawned the search for scaffold molecules that could be used to develop improved neuroprotective pharmacotherapies (8). Among the new molecules discovered, the natural toxin kaitocephalin, isolated from the fungus Eupenicillum shearii, has attracted interest due to the protection it confers to cultured neurons against the excitotoxic death induced by the iGluR agonists kainate and NMDA. Furthermore, it has been reported that kaitocephalin does not show the cytotoxic effects exhibited by other iGluR antagonists, thus becoming a potential candidate for therapeutic use or a scaffold for the discovery of new antiexcitotoxic drugs (9,10). Nonetheless, the specific actions of kaitocephalin on the function of the native glutamate receptors remain unknown. In view of that, we studied the pharmacological properties of the synthetic (−)-kaitocephalin (11) on iGluRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes by endogenous mRNA isolated from rat cerebral cortex and on mGluRs expressed by mRNA from cerebellum. Oocytes injected with mRNA from brain cortex expressed iGluRs and mGluRs in their membranes with properties similar to those previously reported (Figure 1) (12,13). iGluRs were activated by perfusion of 100 μM kainate, which elicited nondesensitizing ion currents (KA currents). KA currents were potentiated to 279% ± 14% (n = 5) by 80 s preincubation with 10 μM cyclothiazide (CTZ), an inhibitor of the desensitization of AMPA-type receptors (14); however 8 min preincubation with 10 μM concanavalin A (Con A), a specific allosteric enhancer of KA-type receptors (15) did not potentiate the current (n = 5), indicating that kainate is mostly activating AMPA-type receptors and a very low number, if any, of Con A-sensitive KA-type receptors (Figure 2a). Perfusion of 10 μM (S)-AMPA elicited ion currents that were 6.3% ± 0.6% (n = 8) of the KA currents in the same oocyte. AMPA currents were potentiated to 126% ± 4% (n = 6) by 10 μM CTZ. The amplitude of the KA currents was dependent on membrane potential and showed substantial but incomplete rectification at positive potentials (Figure 2b,c). The activation of iGluRs by AMPA and the selective potentiation of AMPA currents and KA currents by CTZ but not by Con A indicate that the iGluRs expressed by endogenous mRNA from rat cerebral cortex were mostly AMPA-type native receptors. Moreover, the partial rectification of KA currents to positive voltages also indicates that those AMPA receptors contained the GluR2 subunit (16), probably as heteromers with GluR1 and GluR3, which are the most frequent combinations found in rat brain cortex (2). iGluRs of the NMDA-type were also expressed by mRNA from brain cortex and were evident after coapplication of NMDA with glycine (NMDA currents) (Figure 1), a mandatory coagonist of the receptor (17). NMDA currents showed a fast activation, of variable amplitude between oocytes and mRNA preparations, followed by a slower current that reached a stable steady state during the presence of the agonist. Since NMDA-type receptors are heterodimeric proteins, the NMDA currents that we observed in Xenopus oocytes were most probably made up of the combination of the obligatory subunit NR1, which is ubiquitous in the rat brain, and the NR2A and NR2B subunits that are highly expressed in the adult rat cortex (18).

Figure 1.

Representative ion currents elicited by 100 μM kainate (KA), 300 μM NMDA + 100 μM glycine (Gly), and 10 μM quisqualate in oocytes injected with mRNA from rat cerebral cortex.

Figure 2.

(a) Ion currents elicited by 100 μM kainate were potentiated by 80 s preincubation with 10 μM cyclothiazide (CTZ) but not by 8 min preincubation with 10 μM concanavalin A (Con A) in an oocyte injected with mRNA from cerebral cortex. (b) KA currents elicited by 100 μM kainate at different holding potentials, from −80 to 40 mV in 20 mV intervals. (c) Current−voltage relationships of KA currents from three oocytes. Data are mean ± SEM. Error bars are smaller than the symbols.

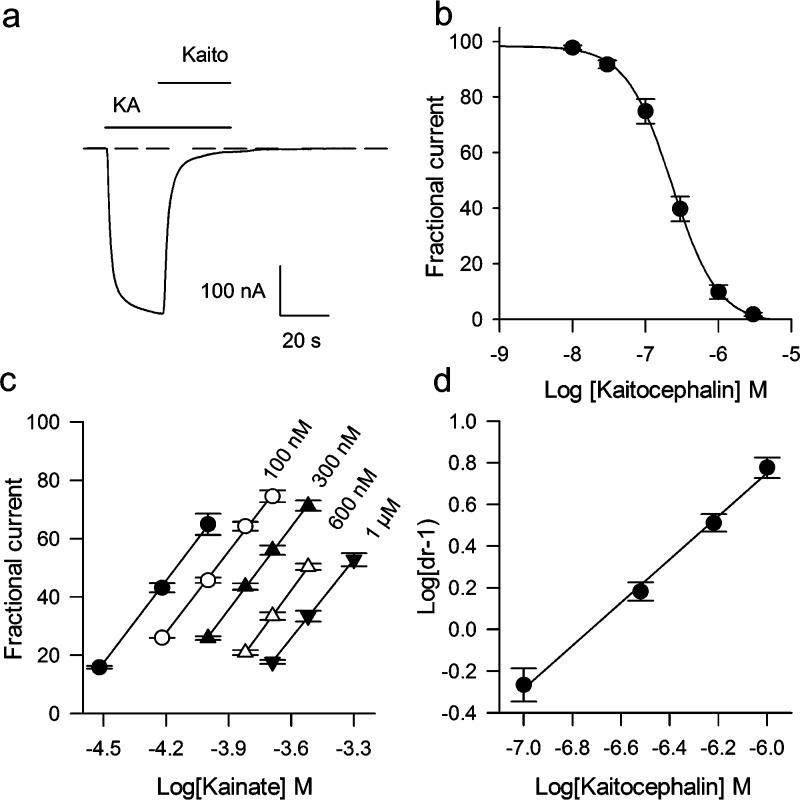

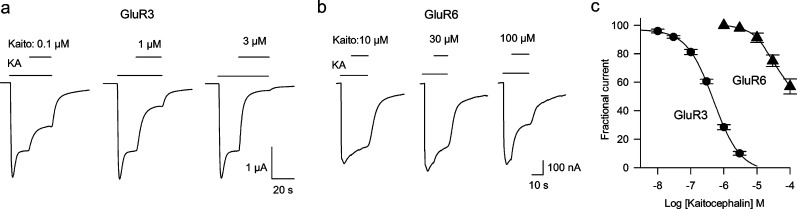

Kaitocephalin action was first evaluated in oocytes expressing endogenous iGluRs from cerebral cortex. Kaitocephalin (100 μM) by itself (n = 6) or when coapplied with 100 μM glycine (n = 6) did not elicit membrane currents on the injected oocytes, beyond a glycine-induced native component (see Figure 5a). This indicates that kaitocephalin has no agonistic activity over the AMPA or NMDA receptors expressed by the rat cortex mRNA. In contrast, the current induced by 100 μM kainate acting on AMPA receptors was completely blocked by an equimolar concentration of kaitocephalin (n = 4), and 3 μM kaitocephalin was sufficient to block the KA current by 98% ± 1%, n = 6 (Figure 3a). The current elicited by 10 μM AMPA was reduced to 31% ± 4% (n = 5) by 300 nM kaitocephalin. Full concentration−response curves of kaitocephalin blocking of KA currents elicited by 100 μM kainate gave an IC50 of 242 ± 37 nM, n = 7 (Figure 3b). To determine whether kaitocephalin is a competitive antagonist of AMPA receptors, Schild plots were constructed following the method described by Verdoorn et al. (19). Partial kainate concentration−response curves were shifted to the right in a parallel manner, and the Schild regression was linear with a slope of 1.03 ± 0.03 (n = 3) consistent with a competitive antagonism (Figures 3c,d). The average pA2 of 6.73 ± 0.06 corresponds to an apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (KB) of 186 (141−229) nM for the block of native AMPA receptors by kaitocephalin. This competitive mode of action over the agonist site of the AMPA receptor is consistent with preliminary modeling of a kaitocephalin-based scaffold docked into the glutamate binding cleft of Gouaux’s X-ray structure (20). We also studied the effects of kaitocephalin on the iGluR receptors expressed by the cloned AMPA-type GluR3 and KA-type GluR6 subunits. These subunits were chosen because they form functional homomeric channels that generate large ionic currents (21,22) and because the GluR6 receptors are more selective to kainate than other homomeric KA-type receptors (23). GluR3 receptors, similarly to the AMPA receptors expressed by mRNA, generated large KA currents that allowed the study of kaitocephalin antagonism without using positive modulators to enhance the current. Interestingly, GluR3 receptors were less sensitive to kaitocephalin (IC50 of 502 ± 55 nM, n = 5; Figure 4a,c) than AMPA receptors expressed from cortical mRNA (IC50 of 242 ± 37 nM, P = 0.002). Application of 100 μM kainate to oocytes expressing GluR6 receptors produced fast activated and fast desensitizing peak currents, followed by a sustained current that was 10% ± 2% (n = 3) reduced by 3 μM kaitocephalin. To reduce the desensitization of GluR6 receptors, the oocytes were preincubated for 8 min in 10 μM Con A (15), and thereafter different concentrations of kaitocephalin on 100 μM KA currents were tested. Similar to the activity in oocytes without incubation in Con A, kaitocephalin was a weak antagonist of GluR6 receptors with an IC50 around 100 μM (n = 6; Figure 4b,c).

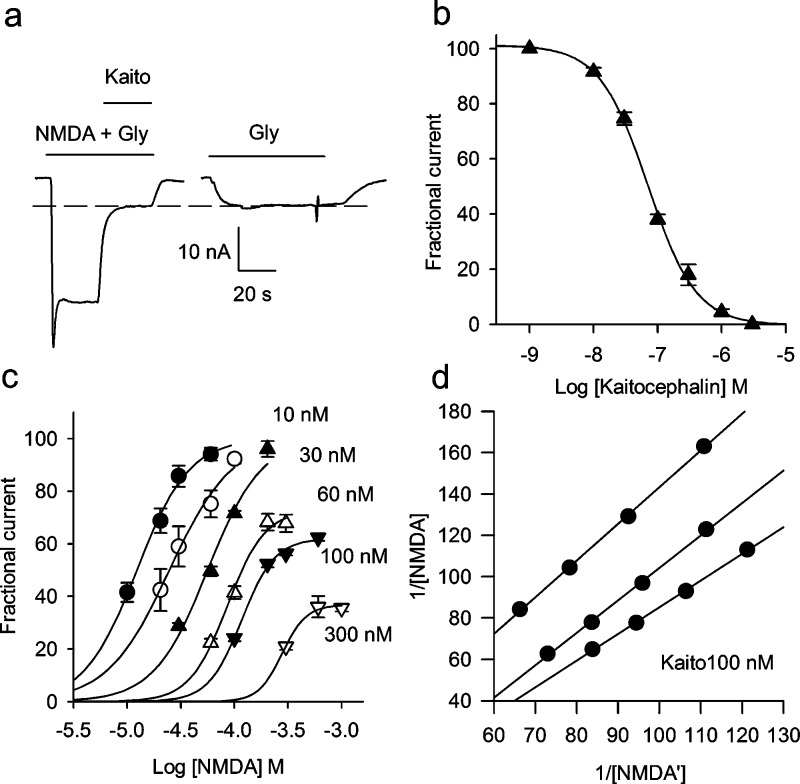

Figure 5.

(a) NMDA receptors activated by 10 μM NMDA + 100 μM glycine. Three micromolar kaitocephalin fully blocked the NMDA current leaving only the current generated by the electrogenic glycine transporter. The interrupted lines indicate the maximum of the current generated by the glycine transporter. (b) Concentration−response curve of the antagonist effect of kaitocephalin on ion currents elicited by 10 μM NMDA + 100 μM glycine, IC50 = 75 ± 9 nM (n = 6). (c, d) Gaddum analyses of the antagonist activity of kaitocephalin on NMDA receptors. (c) Partial concentration−response curves of the agonist effect of NMDA on NMDA receptors in the presence of different concentrations of kaitocephalin reveal a noncompetitive antagonism for higher concentrations of kaitocephalin. Equiactive concentrations of NMDA at levels EC30, EC40, EC50, and EC60 were obtained from logistic fits to the data, and the reciprocals 1/[NMDA] and 1/[NMDA′] were plotted in the Gaddum plot. (d) Gaddum plots for three different oocytes in presence of 100 nM kaitocephalin. The values of the reciprocals of NMDA and NMDA′ (in M) shown are divided by 1000 and 100 to simplify the graph. KB = 12 nM (n = 3).

Figure 3.

Kaitocephalin effects on AMPA-type GluRs expressed by mRNA from rat cerebral cortex. (a) Kaitocephalin (Kaito, 3 μM) block of AMPA receptors activated by 100 μM kainate. The interrupted line indicates the zero of current before kainate perfusion. (b) Concentration−response curve of the antagonist effect of kaitocephalin on ion currents elicited by 100 μM kainate; IC50 of 242 ± 37 nA (n = 7). (c, d) Schild analysis of the antagonist activity of kaitocephalin on AMPA receptors. Dose ratios (dr − 1) at the EC50 levels were obtained from linear regressions to partial concentration−response curves and used to construct the Schild plot (c). The slope of the linear regression to the Schild plot (d) was 1.03 ± 0.03 confirming a competitive mechanism, and the pA2 was 6.73 ± 0.06 for an apparent KB of 186 nM (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Effects of different concentrations of kaitocephalin on currents elicited by 100 μM kainate in two different oocytes expressing GluR3 (a) and GluR6 (b) receptors. Oocytes expressing GluR6 were preincubated with 10 μM concanavalin A to potententiate the responses to kainate. (c) Concentration−response relationships for the homomeric GluR3 (●) and GluR6 (▲) receptors, IC50 of 502 ± 55 nM (n = 5) and ∼100 μM (n = 6).

NMDA receptors were also blocked by kaitocephalin. Figure 5 shows that 3 μM kaitocephalin suppressed completely the current through NMDA receptors gated by coapplication of 10 μM NMDA + 100 μM glycine (n = 6). Because Xenopus oocytes normally express a native electrogenic glycine transporter, caution was taken to determine and subtract this glycine-induced component (1−10 nA) on each of the oocytes recorded. The inhibitory effect of kaitocephalin on NMDA currents was completely reversible with an offset time constant of 25 ± 6 s. Concentration−response curves of the antagonistic effect of kaitocephalin on currents elicited by 10 μM NMDA + 100 μM glycine indicated that kaitocephalin is a more potent antagonist of NMDA receptors (IC50 of 75 ± 9 nM, n = 6; Figure 5b) than of AMPA receptors from rat cerebral cortex (P = 0.0018) or the homomeric GluR3 (P < 0.001). The blocking mechanism of NMDA receptors by kaitocephalin is different than its competitive antagonism on AMPA receptors. Partial NMDA concentration−response curves were shifted to the right in a parallel manner by up to 30 nM of kaitocephalin, and higher concentrations blocked the channel in a noncompetitive fashion (Figure 5c). To estimate the affinity of kaitocephalin on NMDA receptors, Schild plots were constructed for three cells. The average of the linear regression to the data had a slope of less than unity (0.86 ± 0.05). The average pA2 was 7.97 ± 0.2 for an apparent KB of 10.7 (2−22) nM. Since the inhibition was not competitive, the null approach by the method of Gaddum et al. (24) was used to estimate an apparent KB of 11.6 (7−15) nM (n = 3), which was similar to the one estimated from the Schild plot. Whether kaitocephalin is interacting with the pore of the channel, the glycine site, or another site of the NMDA receptor needs further study.

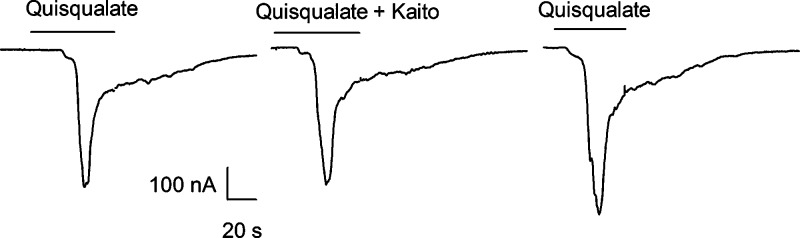

The pharmacological effect of kaitocephalin was also tested on mGluRs. Perfusion of 1 mM glutamate on oocytes injected with rat cortex mRNA elicited a smooth response followed by the generation of long-lasting membrane oscillations, and similar responses were observed during the perfusion of 10 μM quisqualate (Figure 1). These oscillations result from the activation of receptors coupled to PLC, the interplay of the intracellular IP3 signaling cascade, and the final opening of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels located in the plasma membrane of the oocyte (12,25). Since the Xenopus oocyte is able to couple foreign metabotropic receptors that activate the IP3 signaling to its own phosphoinositol cascade signaling, the oscillatory responses elicited by glutamate and by quisqualate most likely are produced by activation of group I mGluR receptors, particularly the mGluR1a, which is strongly expressed in the adult rat cerebral cortex and in cerebellum; although it is possible that mGluR5 also is present in mRNA from rat cortex, its expression is almost absent in the adult cerebellum (26).

In our hands, oocytes injected with mRNA from brain cortex elicited variable metabotropic responses to glutamate that sometimes showed fast desensitization after repetitive stimulation. Therefore we also isolated mRNA from cerebellum, which has larger responses than rat cortex (27,28), and tested kaitocephalin on them. Figure 6 shows that kaitocephalin 3 μM did not suppress the oscillatory activity of mGluRs elicited by 10 μM quisqualate applied to oocytes injected with mRNA from cerebellum.

Figure 6.

Kaitocephalin (3 μM) did not suppress the activation of metabotropic receptors by 10 μM quisqualate in oocytes injected with mRNA isolated from rat cerebellum.

Based on excitotoxicity assays in cultured neurons (9), kaitocephalin was reported to inhibit AMPA/KA receptors in telencephalic and hippocampal neurons and also blocked NMDA but not KA receptors (10,29), although no quantitative data were provided in these latter studies. Using synthetic (−)-kaitocephalin, we find that it inhibits NMDA and AMPA receptors but has only slight effects on KA receptors and practically none on mGluRs expressed in the membranes of Xenopus oocytes. Surprisingly, kaitocephalin’s affinity for cerebral cortex NMDA receptors is about 17 times higher than that of AMPA receptors (apparent KB of 11 vs 186 nM), and kaitocephalin is a more potent antagonist of NMDA than of AMPA receptors from rat brain. Compared with the classical AMPA/KA receptor antagonist 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione (NBQX), kaitocephalin proved to be less potent at GluR3 receptors (65 vs 502 nM), GluR6 receptors (2.76 vs ∼100 μM), and AMPA receptors from cortical mRNA (IC50 of 78 vs 242 nM) (22,30,31). In direct contrast to NBQX, which is ineffective at blocking NMDA receptors at concentrations up to 300 μM (31), kaitocephalin is a potent mixed competitive and noncompetitive NMDA antagonist with an IC50 of 75 nM. Regardless of the origin of the noncompetitive mechanism of kaitocephalin, our results are particularly interesting because overactivity of NMDA receptors is thought to be directly involved in the damage caused by excitotoxicity in the brain (7), and kaitocephalin’s novel pattern of antagonist potencies at the ionotropic receptors (NMDA > AMPA > KA) will help in the design of therapeutic neuroprotective agents. MK801, a noncompetitive and selective blocker of NMDA channels, efficiently inhibits neuronal death by excitotoxicity in animal models (7), but it also produces marked side effects that prevent its use in humans (32). These side effects are thought to be due to its slow and partially irreversible binding to the NMDA receptor (33). Actually, memantine, a noncompetitive and low-affinity antagonist of the NMDA receptor is clinically approved for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, and its reduced side effects are proposed to depend on its fast off-rate (34). Since kaitocephalin binding is rapidly and completely reversible, it is possible that drugs based on this structure may show fewer adverse effects than MK801 or other ionotropic glutamate receptors antagonists. In this regard, we are developing the core structure of this natural product as a core scaffold on which to base a new family of antagonists as potential therapeutic agents (20).

Methods

mRNA Isolation

Total RNA from adult rat cerebral cortex and from cerebellum was isolated by the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and mRNA was then isolated using the Oligotex kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Rat glutamate receptors GluR3o (flop variant) and the GluR6(R) edited version cDNAs were obtained from Stephen F. Heinemann at the Salk Institute. The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli Top10 strain for storage and amplification. Linearized plasmids were used as templates for cRNA synthesis using Ambion’s mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Fifty nanoliters of mRNA or cRNA (concentration 1 mg/mL) were injected into stage V−VI Xenopus oocytes (35). Injected oocytes were kept in Barth’s solution [88 mM NaCl, 0.33 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 mM CaCl2, 1 mM KCl, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)] with penicillin 100 U/mL and streptomycin 0.1 mg/mL (Sigma; St Louis, MO) added at 16−17 °C until the moment of recording.

Electrophysiological Assay

Three to four days after injection, oocytes were impaled with two microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl and voltage clamped at −80 mV using a two electrode voltage-clamp amplifier (36). Oocytes were continuously perfused with gravity-driven frog Ringer’s solution [115 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)] at room temperature (19−21 °C). Data acquisition was performed using WinWCP V 3.9.4 (John Dempster, Glasgow, United Kingdom). The (−)-kaitocephalin used in these studies was prepared by chemical synthesis as described by Vaswani and Chamberlin (11) and was >98% pure based on 1H NMR, 13C NMR, high-resolution mass spectrometry, optical rotation, and HPLC/MS, all consistent with data reported for the natural compound. NMDA, glutamate, and Con A were purchased from Sigma. CTZ and kainic acid were from Tocris (Ellisville, MO).

Data Analysis

The antagonist activity of kaitocephalin on KA currents or NMDA currents was determined by measuring the percent inhibition produced by different concentrations of kaitocephalin. The concentration of kaitocephalin causing a decrease to 50% of the KA or NMDA currents (IC50) was estimated by fitting the following logistic equation to the experimental data: I(x) = Imin + (Imax − Imin)/[1 + (x/IC50)k], (SigmaPlot 10), where x is the concentration of kaitocephalin (in M), I is the amplitude of the agonist response (in nA), and k is the slope of the curve. Antagonist potency of AMPA receptors was determined by Schild plots using the method described by Verdoorn et al. (19). Briefly, the maximum response in the steady state of each oocyte was obtained with 300 μM kainate. Partial concentration−response curves containing the concentration activating half of the maximum response (EC50) were constructed in control conditions (no kaitocephalin) and in presence of different concentrations of kaitocephalin. Oocytes were perfused for at least 5 min with kaitocephalin before perfusion of kainate. The EC50 for each agonist curve was estimated from the linear regression to the experimental data. EC50 dose ratios (dr) of kainate were calculated and plotted vs concentration of kaitocephalin according to the equation log(dr − 1) = log[kaitocephalin] − log KB. The slope was calculated from the linear regression of the Schild plot, and the KB and its respective pA2 were calculated from the intercept of the linear regression, where log(dr − 1) = 0. For estimates of kaitocephalin affinity on NMDA receptors, Schild plots were constructed using 300 μM NMDA + 100 μM glycine to obtain the maximal NMDA current. Since NMDA currents can show rundown, the maximum current was tested before and after each agonist concentration−response curve. Since kaitocephalin has mixed competitive and noncompetitive antagonistic effects on NMDA receptors, the affinity was estimated by the method of Gaddum et al. (24). Briefly, logistic equations of the form I(x) = Imin + (Imax − Imin)/[1 + (x/EC50)k] were fitted to partial NMDA agonist curves, and the equiactive concentrations at EC30, EC40, EC50, and EC60 in the absence and in the presence of different concentrations of kaitocephalin (10, 30, 60, 100, and 300 μM) were calculated from those curves. The reciprocals of the equiactive concentrations are correlated according to the equation 1/[NMDA] = (1/[NMDA′])(1 + [kaitocephalin]/KB) + (α[kaitocephain])/(KAKB)), where [NMDA] is the concentration of agonist (in M) in absence of kaitocephalin, [NMDA′] is the equiactive concentration in presence of a specific concentration of kaitocephalin (in M), α is a modifying term that denotes the change in affinity of one ligand produced by binding of the other, and KA is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the agonist (37). Since the reciprocals 1/[NMDA] and 1/[NMDA′] are linearly correlated, they were plotted, and the linear regression to these data was used to calculate the KB, using the equation KB = [kaitocephalin]/(slope − 1) (24,37). Experimental data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by Student t-test and considered significant when P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Dempster for kindly providing the WinWCP.

Abbreviations

iGluR, ionotropic glutamate receptors; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptors; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; KA, kainate; CTZ, cyclothiazide; Con A, concanavalin A; IP3, inositol triphosphate; Hepes, N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid.

R.G.V. and A.R.C. synthesized the (―)-kaitocephalin, J.M.R-R. did the molecular biology work, R.M. and A.L. did the electrophysiological and pharmacological experiments. All authors participated in the experimental design and writing of the paper.

This work was supported by the American Health Assistance Foundation (Grant A2006-054 to R.M.), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (Grant NS-27600 to A.R.C.) and the King Abdul Aziz City for Science and Technology (Grant KACST-46749 to R.M.).

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Ferraguti F.; Shigemoto R. (2006) Metabotropic glutamate receptors. Cell Tissue Res. 326, 483–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R.; Borges K.; Bowie D.; Traynelis S.-F. (1999) The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 51, 7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagni L.; Ango F.; Perroy J.; Bockaert J. (2004) Identification and functional roles of metabotropic glutamate receptor-interacting proteins. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15, 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Antoni S.; Berretta A.; Bonaccorso C.-M.; Bruno V.; Aronica E.; Nicoletti F.; Catania M.-V. (2008) Metabotropic glutamate receptors in glial cells. Neurochem. Res. 33, 2436–2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J.-D.; Huganir R.-L. (2007) The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 613–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia L.-V.; Kalia S.-K.; Salter M.-W. (2008) NMDA receptors in clinical neurology: Excitatory times ahead. Lancet Neurol. 7, 742–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villmann C.; Becker C.-M. (2007) On the hypes and falls in neuroprotection: Targeting the NMDA receptor. Neuroscientist 13, 594–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.; Shaked I.; Fisher J.; Mizrahi T.; Schori H. (2003) Protective autoimmunity against the enemy within: Fighting glutamate toxicity. Trends Neurosci. 26, 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin-Ya K.; Kim J.-S.; Furihata K.; Hayakawa Y.; Seto H. (1997) Structure of kaitocephalin, a novel glutamate receptor antagonist produced by Eupenicillium shearii. Tetrahedron Lett. 38, 7079–7082. [Google Scholar]

- Shin-Ya K. (2005) Novel antitumor and neuroprotective substances discovered by characteristic screenings based on specific molecular targets. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 69, 867–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani R.-G.; Chamberlin A.-R. (2008) Stereocontrolled total synthesis of (−)-kaitocephalin. J. Org. Chem. 73, 1661–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen C.-B.; Miledi R.; Parker I. (1984) Glutamate and kainate receptors induced by rat brain messenger RNA in Xenopus oocytes. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 221, 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter M.-K.; Parker I.; Miledi R. (1992) Messenger RNAs coding for receptors and channels in the cerebral cortex of adult and aged rats. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 13, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile S.; Miledi R.; Eusebi F. (2006) Effects of cyclothiazide on GluR1/AMPA receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 2943–2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts I.; Petroski R.; Kizelsztein P.; Teichberg V.-I.; Heinemann S.-F.; Hollmann M. (1999) Lectin-induced inhibition of desensitization of the kainate receptor GluR6 depends on the activation state and can be mediated by a single native or ectopic N-linked carbohydrate side chain. J. Neurosci. 19, 916–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M.; Hartley M.; Heinemann S. (1991) Ca2+ permeability of KA-AMPA--gated glutamate receptor channels depends on subunit composition. Science 252, 851–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy S.-G.; Leszkiewicz D.-N. (2004) Role of distinct NMDA receptor subtypes at central synapses. Sci. Signaling re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monyer H.; Burnashev N.; Laurie D.-J.; Sakmann B.; Seeburg P.-H. (1994) Developmental and regional expression in the rat brain and functional properties of four NMDA receptors. Neuron 12, 529–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn T.-A.; Kleckner N.-W.; Dingledine R. (1989) N-methyl-D-aspartate/glycine and quisqualate/kainate receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes: Antagonist pharmacology. Mol. Pharmacol. 35, 360–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani R.-G.; Limon A.; Reyes-Ruiz J.-M.; Miledi R.; Chamberlin A.-R. (2009) Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a scaffold for iGluR ligands based on the structure of (−)-kaitocephalin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egebjerg J.; Bettler B.; Hermans-Borgmeyer I.; Heinemann S. (1991) Cloning of a cDNA for a glutamate receptor subunit activated by kainate but not AMPA. Nature 351, 745–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limon A.; Reyes-Ruiz J.-M.; Eusebi F.; Miledi R. (2007) Properties of GluR3 receptors tagged with GFP at the amino or carboxyl terminus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15526–15530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange M.; Bräuner-Osborne H.; Jensen A.-A. (2006) Functional characterisation of homomeric ionotropic glutamate receptors GluR1-GluR6 in a fluorescence-based high throughput screening assay. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening 9, 147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddum J.-H.; Hameed K.-A.; Hathway D.-E.; Stephens F.-F. (1955) Quantitative studies of antagonists for 5-hydroxitryptamine. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 40, 49–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker I.; Miledi R. (1986) Changes in intracellular calcium and in membrane currents evoked by injection of inositol trisphosphate into Xenopus oocytes. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 228, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casabona G.; Knöpfel T.; Kuhn R.; Gasparini F.; Baumann P.; Sortino M.-A.; Copani A.; Nicoletti F. (1997) Expression and coupling to polyphosphoinositide hydrolysis of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in early postnatal and adult rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 9, 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale D.; Gant D.-B.; Anis N.-A.; Eldefrawi A.-T.; Eldefrawi M.-E.; Konno K.; Miledi R. (1989) Inhibition of rat brain glutamate receptors by philanthotoxin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 251, 156–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi T.; Asanuma A.; Yanagisawa K.; Anzai K.; Goto S. (1989) Regional distribution of metabotropic glutamate response in the rat brain using Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci. Lett. 105, 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H.; Shin-Ya K.; Furihata K.; Hayakawa Y.; Seto H. (2001) Absolute configuration of a novel glutamate receptor antagonist kaitocephalin. Tetrahedron Lett. 42, 4021–4023. [Google Scholar]

- Bleakman R.; Schoepp D.-D.; Ballyk B.; Bufton H.; Sharpe E.-F.; Thomas K.; Ornstein P.-L.; Kamboj R.-K. (1996) Pharmacological discrimination of GluR5 and GluR6 kainate receptor subtypes by (3S,4aR,6R,8aR)-6-[2-(1(2)H-tetrazole-5-yl)ethyl]decahydroisdoquinoline-3 carboxylic-acid. Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randle J.-C.; Guet T.; Cordi A.; Lepagnol J.-M. (1992) Competitive inhibition by NBQX of kainate/AMPA receptor currents and excitatory synaptic potentials: Importance of 6-nitro substitution. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 215, 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D.; von Haebler D.; Winter C.; Juckel G.; Heinemann U. (2008) A single application of MK801 causes symptoms of acute psychosis, deficits in spatial memory, and impairment of synaptic plasticity in rats. Hippocampus 18, 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong E.-H.; Kemp J.-A.; Priestley T.; Knight A.-R.; Woodruff G.-N.; Iversen L.-L. (1986) The anticonvulsant MK-801 is a potent N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 7104–7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.-S.-V.; Lipton S.-A. (2006) The chemical biology of clinically tolerated NMDA receptor antagonists. J. Neurochem. 97, 1611–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R.; Parker I.; Sumikawa K. (1982) Properties of acetylcholine receptors translated by cat muscle mRNA in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1, 1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R. (1982) A calcium-dependent transient outward current in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 215, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz M., Kenakin T. (1999) Measurement of drug affinity, in Quantitative Molecular Pharmacology and Informatics in Drug Discovery, pp 34−62, John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, England. [Google Scholar]