Abstract

Background and purpose:

Limited data on the brain penetration of potential stroke treatments have been cited as a major weakness contributing to numerous failed clinical trials. Thus, we tested whether interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), established as a potent inhibitor of brain injury in animals and currently in clinical development, reaches the brain via a clinically relevant administration route, in experimental stroke.

Experimental approach:

Male, Sprague-Dawley rats [either naïve or exposed to middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo)] were given a single s.c. dose of IL-1RA (100 mg·kg−1). The pharmacokinetic profile of IL-1RA was assessed in plasma and CSF up to 24 h post-administration. Brain tissue distribution of administered IL-1RA was assessed using immunohistochemistry. In a separate experiment, the neuroprotective effect of the single s.c. dose of IL-1RA in MCAo was assessed versus a placebo control group.

Key results:

A single s.c. dose of IL-1RA reduced damage caused by MCAo by 33%. This dose resulted in sustained, high concentrations in plasma and CSF, penetrated brain tissue exclusively in areas of blood–brain barrier breakdown and co-localized with morphologically viable neurones. CSF concentrations did not reflect massive parenchymal infiltration of IL-1RA in MCAo animals compared to naïve.

Conclusions and implications:

These data are the first to show that a potential treatment for stroke, IL-1RA, rapidly reaches salvageable brain tissue via an administration route that is clinically relevant. This allows confidence that IL-1RA, as a candidate for further clinical development, is able to confer its protective actions both peripherally and centrally.

Keywords: brain penetration, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, cerebral ischaemia, inflammation, neuroprotection

Introduction

Cerebral ischaemia in stroke is characterized by a sudden interruption of blood supply to the brain, and is a leading cause of death and disability (Hankey, 2003). Despite intense research (approaching 200 clinical trials), only one stroke treatment has been approved for clinical use, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, and strict patient eligibility criteria means only a small percentage of patients receive the drug (Huang et al., 2006). Poor translational success has often been ascribed to limitations of both pre-clinical and clinical studies. The low predictive validity of the pre-clinical animal models, the heterogeneity of the patient population and the lack of rigorous evaluation of the pharmacokinetics of novel therapeutics have been reviewed extensively (Savitz and Fisher, 2007; Donnan, 2008; Philip et al., 2009). Therefore, pre-clinical research needs to target new and existing areas with improved rigour to avoid more clinical failures (Macleod et al., 2009).

The inflammatory response is now well established as a contributor to ischaemic brain damage (Wang et al., 2007). The pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-1 (IL-1) contributes to injury induced by experimental cerebral ischaemia, and is implicated in clinical subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and stroke (Allan et al., 2005). IL-1 exists as two separate ligands, IL-1α and IL-1β. They exert similar biological effects by binding the membrane-bound IL-1 receptor I (IL-1R1), which then associates with two IL-1 receptor accessory proteins IL-1RAcP and IL-1RAcPb to form a complex that allows intracellular signalling and an induction of downstream inflammatory mediators (Korherr et al., 1997; Allan et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2009). IL-1α and IL-1β are synthesized by many cell types of both the peripheral and central immune system, including astrocytes, microglia, neutrophils, lymphocytes and monocytes (Allan et al., 2005). The mechanisms of action of IL-1 appear complex and are not fully understood, but include release of neurotoxins (notably matrix metalloproteinase-9) from astrocytes (Thornton et al., 2008), activation of brain endothelium (Konsman et al., 2004), stimulation and invasion of leucocytes (Bernardes-Silva et al., 2001; McColl et al., 2007) and actions on the extracellular matrix (McColl et al., 2008; Summers et al., 2009). The naturally occurring IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) binds competitively to IL-1R1, blocks all actions of IL-1α and IL-1β and is therefore of potential benefit as a treatment (Hannum et al., 1990). Endogenous IL-1RA mRNA is up-regulated after stroke (Denes et al., 2008), but appears unable to sufficiently antagonize the effects of IL-1 after ischaemia. Many pre-clinical studies show that centrally administering exogenous IL-1RA is protective in experimental stroke, even when administered 3 h after the insult (Loddick and Rothwell, 1996; Mulcahy et al., 2003; Allan et al., 2005). Brain penetration of peripherally administered IL-1RA is limited (Gutierrez et al., 1994) due to the presence of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), and the hydrophilic nature and large size (17 kDa) of the peptide, possibly limiting its utility as a treatment in brain injury. Despite this, pre-clinical studies show that peripherally administered IL-1RA is neuroprotective; it reduces ischaemic brain damage in rodents when administered as an intravenous bolus and infusion (Clark et al., 2008) or with multiple s.c. injections (Relton et al., 1996). In these studies, using a model of temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in rat, infarct volume does not evolve after 24 h (Mulcahy et al., 2003), and the neuroprotective effects of IL-1RA are almost identical whether measured 24 h or 7 days post-occlusion (Loddick and Rothwell, 1996).

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats show the maintenance of IL-1RA concentrations in plasma (∼10 000 ng·mL−1) and CSF (∼100 ng·mL−1), with an intravenous infusion for 24 h, affords neuroprotection (Clark et al., 2008). It is not clear whether IL-1RA needs to be delivered continuously to retain this effect. Clinically, IL-1RA is safe in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and in a small phase II study in acute stroke. IL-1RA significantly reduced circulating inflammatory markers in stroke patients, and had a potentially beneficial effect on outcome at 2–3 months (Emsley et al., 2005). Pharmacokinetic studies in SAH patients show that intravenously administered IL-1RA rapidly reaches experimentally therapeutic concentrations in CSF (Gueorguieva et al., 2007; Clark et al., 2008). However, it is not known whether the concentration profile of IL-1RA in the CSF reflects that in brain tissue, how this relates to neuroprotection or if a single s.c. injection is effective.

The aim of this study was to test whether a single s.c. dose of IL-1RA achieves similar neuroprotective and pharmacokinetic profiles as intravenous administration in rat stroke, and, secondly, to determine whether IL-1RA penetrates brain tissue. This study was the basis for planned clinical studies in acute stroke and SAH.

Methods

Rats

Studies were conducted on male, Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Margate, Kent, UK) weighing 300–550 g under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. The animals were kept under a 12 h light–dark cycle with free access to food and water.

Focal cerebral ischaemia

Focal cerebral ischaemia was induced by 90 min transient occlusion of the MCAo. Briefly, anaesthesia was induced (4%) and maintained (1.5%) by inhalation of isoflurane, 70% N2O and 30% O2, and core body temperature was maintained throughout the procedure at 37.0 ± 0.5°C. A 3-0 nylon monofilament (Dermalon, Tyco Healthcare UK Ltd, Gosport, UK), with silicone-coated tip (350 µm diameter), was introduced into the external carotid artery and advanced ∼18 mm along the internal carotid artery to occlude the MCA, verified by a >60% drop in laser Doppler signal (Moor Instruments Ltd, Devon, UK). After 90 min, the filament was withdrawn to establish reperfusion. It was decided, a priori, that animals without cortical lesions were to be excluded from the study (32%) on the grounds they did not represent a 90 min occlusion in our hands.

Infarct volume

Rats were subjected to 90 min MCAo then 22.5 h reperfusion, and received a single s.c. dose of human-IL-1RA (r-met-huIL-1RA: Kineret; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA) (100 mg·kg−1) or placebo (Amgen) at the time of occlusion. Twenty-four hours after MCAo, the animals were killed by cervical dislocation, and their brains were removed and snap frozen. Nissl-stained coronal sections were scanned digitally using ImageJ software, and infarct areas calculated, adjusting for oedema. The volume of damage was calculated by integration of areas of damage with the distance between coronal levels.

Animals were allocated to treatment group using computer-generated randomization schedules (GraphPad Prism 5, Software Inc. 2009), and the operator was blinded to treatment. Analysis of infarct volume was performed without knowledge of experimental grouping.

Pharmacokinetics

In a separate study, a single s.c. dose of IL-1RA (100 mg·kg−1) was administered at the time of occlusion, in the right flank. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture, and CSF by cisterna magna puncture 15, 30, 60 min and 12 h later in naïve animals, and at 2, 4, 8, 18, 24 h in naïve and MCAo animals, post-injection. Blood was centrifuged at 800× g, and plasma supernatant was sampled. Plasma and CSF samples were stored at −20°C for up to 4 weeks until analysis. The rats were perfused transcardially with saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Assays for IL-1RA were performed by elisa as described previously (Emsley et al., 2005). Minimum sensitivity of the assay was 38 pg·mL−1. Inter-assay coefficients of variation, determined in the appropriate working range, were 15% at 38 pg·mL−1. According to the manufacturer (BioSource, Nivelles, Belgium), the antibody shows 5–10% cross-reactivity with rat IL-1RA. However, using this antibody, we were unable to detect any IL-1RA in plasma or CSF of animals not receiving exogenous IL-1RA.

Immunohistochemistry

In rats used for pharmacokinetic studies, brain penetration of IL-1RA was studied by immunohistochemistry using a specific antibody directed against IL-1RA (R&D Systems Europe, Oxon, UK) diluted 1:500 on 30 µm thick free-floating brain sections; staining was visualized with 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride (DAB) with nickel ammonium sulphate intensification. BBB disruption was assessed from brain penetration of endogenous rat IgG using a biotinylated anti-IgG diluted 1:500 (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) visualized with DAB alone. Nissl and nuclear fast red counterstains were used to assess cell morphology. In Nissl-counterstained brain sections, the total number of morphologically viable cells in the area of IL-1RA infiltration, and those positive for IL-1RA, were counted. Double-labelling immunofluorescence with the above antibodies and an antibody directed against the neuronal marker NeuN (Chemicon, Hampshire, UK), was visualized with the appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antisera to assess co-localization. To ensure the anti-human IL-1RA antibody did not cross-react with endogenous IL-1RA, sections from MCAo animals receiving placebo were stained with the anti-human IL-1RA. In addition, infarcted tissue was immunostained with the IL-1RA antibody pre-absorbed with excess IL-1RA (3 mg·mL−1) in rats that had received human-IL-1RA.

All drug and molecular target nomenclature conform to the British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2008).

Statistics

Data were analysed using Student's t-test for single comparisons and one-way anova followed with Bonferroni's correction multiple comparisons (GraphPad Prism 5, Software Inc. 2009).

Results

Protection: a single s.c. dose was neuroprotective

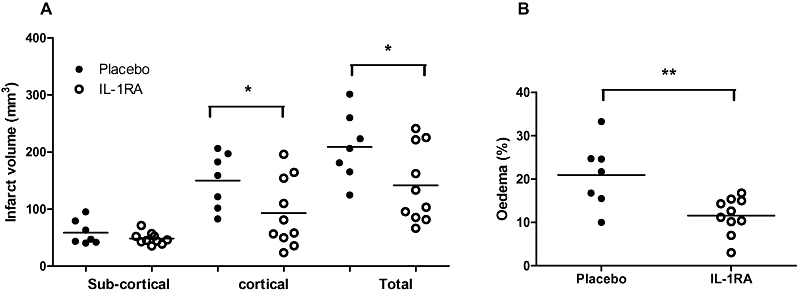

A single s.c. dose of IL-1RA significantly reduced lesion volume by 33% compared to placebo treatment (P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). This was due to a significant reduction in cortical lesion volume (39%) in IL-1RA-treated animals versus placebo. IL-1RA significantly reduced oedema by 57% (from 21 to 12%) compared to placebo treatment 24 h after occlusion (P < 0.01) (Figure 1B). We have shown previously that IL-1RA has no significant effect on physiological parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate and body temperature in rat MCAo (Loddick and Rothwell, 1996).

Figure 1.

Neuroprotective effects of IL-1RA. (A) Total and cortical infarct volumes are reduced following administration of IL-1RA (100 mg·kg−1 s.c.) at 22.5 h post-MCAo. (B) Oedema, measured as the percentage size of the contralateral hemisphere, was significantly reduced by IL-1RA at 22.5 h post-MCAo. *P < 0.05, one-way anova with Bonferroni correction. **P < 0.01, Student's t-test.

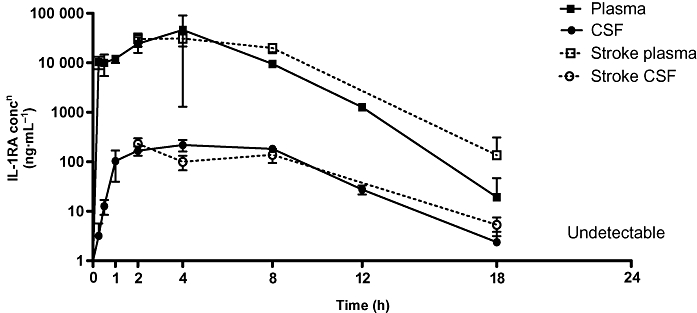

Pharmacokinetics: a single s.c. dose of IL-1RA sustained plasma and CSF levels for 8 h

After a single s.c. injection of IL-1RA, concentrations in plasma increased rapidly to 10 350 ng·mL−1 (±2940 ng·mL−1) by 15 min, and were sustained above this level for 8 h (9530 ± 630 ng·mL−1). CSF concentrations increased more slowly to 100 ng·mL−1 (±65 ng·mL−1) at 1 h, and were maintained at a mean concentration of 170 ng·mL−1 (±50 ng·mL−1) between 1 and 8 h. Levels of IL-1RA decreased in both plasma and CSF after 8 h to undetectable levels at 24 h. The maximum concentration (Cmax) and time to maximum concentration (Tmax) in naïve animals were 46 027 ± 44 778 ng·mL−1 in plasma, and 217 ± 56 ng·mL−1 in CSF at 4 h. In stroke animals, Cmax was 30 882 ± 9481 ng·mL−1 in plasma, and 229 ± 67 ng·mL−1 in CSF at Tmax 4 h. The pharmacokinetic profile of MCAo animals did not differ significantly from naive animals (Figure 2). The profile of plasma and CSF concentrations over the initial 8 h closely mirrored previously published pharmacokinetic profiles of IL-1RA in plasma and CSF after an intravenous bolus (10 mg) and infusion (0.8 mg·h−1) in the rat (Clark et al., 2008). A large concentration gradient of IL-1RA between plasma and CSF was seen; maximal levels in CSF were only 2% of that in plasma. Human data show similar plasma : CSF ratios peaking at 4% (Gueorguieva et al., 2007).

Figure 2.

IL-1RA pharmacokinetics. Concentration of IL-1RA in rat blood (plasma) and CSF after s.c. injection (100 mg·kg−1). Data are expressed as mean concentration (±SD) in naïve animals at 15 (n= 6), 30 min (n= 5), and 1 (n= 4), 2 (n= 2), 4, 8, 12 (n= 3), 18 and 24 h (n= 2), and in MCAo animals at 2 (n= 5), 4 (n= 4), 8 (n= 3), 18 (n= 2) and 24 h (n= 3).

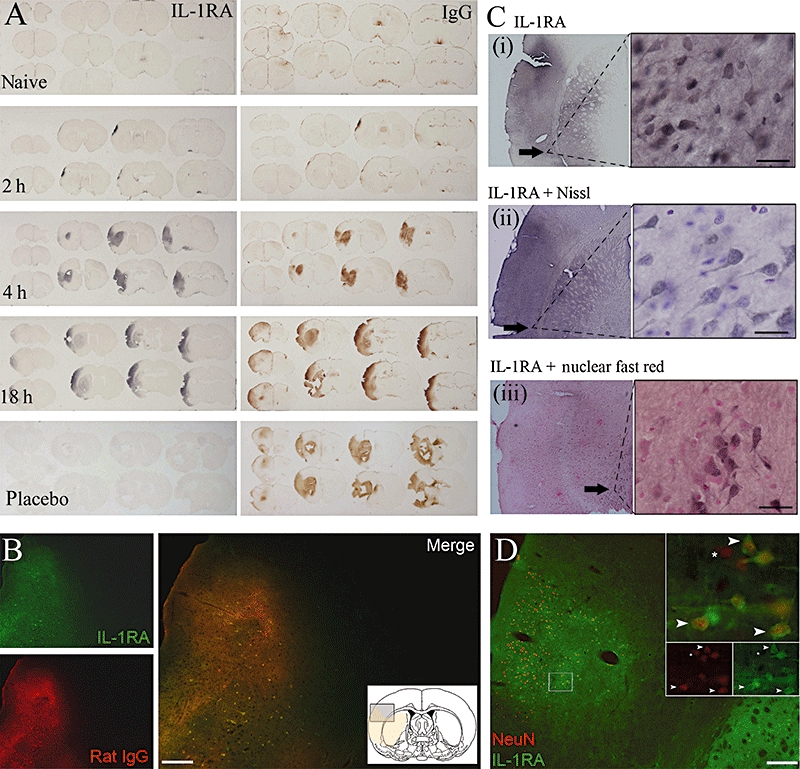

Distribution: a single s.c. dose of IL-1RA penetrated ischaemic brain tissue

Strong immunoreactivity for human IL-1RA was detected in brain parenchyma 2 h after MCAo. Immunoreactivity for IL-1RA correlated with BBB breakdown (as shown by immunostaining for plasma-derived IgG). The IL-1RA immunopositive area increased over time (2–18 h), correlating with evolvement of BBB damage and suspected infarct progression (Figure 3A). Immunofluorescence further confirmed this with a high degree of co-localization of IL-1RA and IgG (Figure 3B). Histological analysis revealed that IL-1RA was present in salvageable tissue as it co-localized with morphologically viable neurones (Figure 3C) and with the neuronal marker, NeuN (Figure 3D). The percentage of morphologically viable neurones in the area of BBB breakdown positive for IL-1RA ranged from 65 to 81% at 4 h (n= 3). The anti-human IL-1RA antibody did not cross-react with endogenous rat IL-1RA as no staining was observed in placebo-treated animals after MCAo (Figure 3A). The specificity of the antibody was also confirmed, as no immunostaining was seen on infarcted tissue processed with IL-1RA antibody, pre-absorbed with excess IL-1RA (3 mg·mL−1), in rats injected with human IL-1RA.

Figure 3.

Distribution of IL-1RA. (A) IL-1RA (left panels) and endogenous rat IgG (right panels) in naïve and 2, 4 and 18 h after MCAo with simultaneous administration of IL-1RA (100 mg·kg−1 s.c.). Adjacent sections demonstrate almost identical infiltration patterns of IL-1RA and rat IgG. Bottom panels show placebo-injected control 24 h after MCAo. (B) Double-immunofluorescence images demonstrating co-localization of IL-1RA with rat IgG and (D) IL-1RA with NeuN. (D) Inserts show high magnification of co-localized IL-1RA and NeuN (top), and single fluorescent channel images of NeuN (below left) and IL-1RA (below right). Arrows indicate co-localized cells; asterisks indicate NeuN-positive cells without IL-1RA. Images (B) and (D) were taken from adjacent brain sections. (C) Morphologically viable neurones demonstrated with: (i) IL-1RA antibody alone; (ii) IL-1RA antibody with Nissl counterstain; and (iii) IL-1RA with nuclear fast red counterstain. Black arrows indicate regions of high magnification. (B–D) Obtained 4 h post-MCAo. Black scale bars = 20 µm; white scale bars = 200 µm.

Discussion and conclusions

Inadequate data on brain penetration of potential stroke treatments have been cited as a contributor to failed phase III clinical trials in stroke (Savitz and Fisher, 2007). This study provides clear evidence that IL-1RA, a stroke therapy currently in clinical development, penetrates brain tissue extensively after experimental stroke. Importantly, this occurs early, before the potential collapse of the penumbra, and was co-localized with morphologically viable neurones. Brain penetration appeared to be dependent on BBB breakdown as IL-1RA infiltration correlated almost identically with endogenous rat IgG brain infiltration, paradoxically indicating the greater the damage post-stroke, the greater access for treatment.

Disruption of the BBB following stroke is believed to be biphasic, potentially limiting therapeutic time windows in which compounds can be delivered to the brain (Kuroiwa et al., 1985; Belayev et al., 1996). However, exact temporal dynamics have yet to be identified. More recent studies have indicated that the BBB is disrupted for up to 24 h (Pillai et al., 2009) or that BBB leakage is continuous for days (Durukan et al., 2009) and weeks (Strbian et al., 2008) after experimental transient focal cerebral ischaemia. Clinically, magnetic resonance imaging of stroke patients reveals that the BBB can become disrupted early after stroke onset (estimated median onset time of 3.8 h) and is associated with poor outcome (Latour et al., 2004; Warach and Latour, 2004). These studies, coupled with the present data, indicate that restricted access of neuroprotectants to brain tissue may not be a major limiting factor in focal ischaemia, and that CSF concentrations do not necessarily reflect brain levels at least in the rat.

IL-1RA may also be transported actively across the BBB. Active transport of IL-1RA across the BBB has been reported in vitro (Skinner et al., 2009) and in mice in vivo (Gutierrez et al., 1994). This was at very low levels [between 0.33 and 0.65% of an intravenous dose of IL-1RA entered each gram of mouse brain (Gutierrez et al., 1994)]. If similar levels are transported actively in rat, we were unable to detect IL-1RA immunohistochemically in regions of intact BBB; this may reflect sensitivity of the measures we used. However, the large amounts of IL-1RA detected in areas of BBB breakdown suggest that any protective action IL-1RA has in the brain is likely to result from penetration through the damaged BBB, although up-regulation of an as yet unidentified IL-1RA transport mechanism cannot be ruled out (Banks et al., 1995). Although the present data show penetration of IL-1RA into the brain tissue, we did not obtain evidence of IL-1RA binding to its target receptor in the brain, IL-1R1, and further studies are needed to show their co-localization in brain tissue.

There is now extensive evidence that anti-inflammatory treatments, such as IL-1RA, may act outside the brain to confer their neuroprotective effect. Peripheral inflammatory and immune responses influence both the incidence of stroke and subsequent clinical response and outcome (Price et al., 2003; Offner et al., 2005; Chapman et al., 2009; McColl et al., 2009). It is difficult to dissect the relative contribution of central and peripheral inflammation to brain tissue damage in stroke, and both are likely to contribute, but this study shows that a peripherally administered neuroprotective dose of IL-1RA reaches both areas. The importance of this is highlighted by the current climate in stroke research, which has led to the creation of guidelines, recently updated, by the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable Preclinical Recommendations (STAIR) committee to try and reverse the well-documented translation of pre-clinical success to clinical failure (Fisher et al., 2009). The present study attempts to fill further gaps in pre-clinical research by providing evidence of the brain penetration of IL-1RA.

Similar CSF concentrations were observed after s.c. administration in naïve and MCAo animals, which did not reflect the massive parenchymal infiltration of IL-1RA solely in the MCAo group. The results indicate that CSF levels of molecules usually restricted from entering the intact brain are not informative of brain tissue levels in cerebral ischaemia. This suggests that measuring CSF concentrations of potential therapeutic agents may not be an adequate indicator of brain penetration. In addition, high CSF concentrations may reduce oedema formation and intracranial pressure independently of focal BBB damage in traumatic brain injury (Hutchinson et al., 2007). Our results indicate that unless the CSF–brain barrier is affected by focal ischaemia, causing disruption similar to the effects of ischaemia on the BBB, plasma concentrations of drug may be as important as CSF concentrations when determining pharmacokinetic profiles. The relative efficacy of IL-1RA from within the CSF compared to its effects from the blood was not investigated in the present study. However, SAH patients developing vasospasm (a major risk factor for poor outcome) demonstrate significantly higher values of the inflammatory cytokine, IL-6, in CSF, which precedes the secondary insult (Schoch et al., 2007). Therefore, investigation of CSF drug concentrations is merited, but may have limited value for prediction of brain tissue concentrations.

The minimum therapeutic dose of IL-1RA in experimental models of stroke is currently unknown. However, experimentally therapeutic doses of IL-1RA are rapidly achievable in man and extremely well tolerated (J. Galea, unpubl. data), but further pharmacokinetic studies are needed to determine the minimum effective dose. Recently, a small peptide IL-1RA mimetic has also shown to be effective in in vivo models of inflammation (Quiniou et al., 2008), and may provide a more brain penetrant alternative to IL-1RA that warrants further investigation.

A single s.c. dose of IL-1RA resulted in sustained high concentrations in plasma and CSF, similar to those achieved with intravenous bolus and infusion (Clark et al., 2008). One caveat of the study is that the weight-adjusted dose used may be too high for clinical use. However, lower, more frequent s.c. dosing as used to treat RA may also provide sustained concentrations in plasma and result in steady predictable concentrations within CSF (J. Galea, unpubl. data). This may be important as an easily administered, sustained, anti-inflammatory treatment for stroke. It also has implications for the potential prophylactic treatment of delayed cerebral ischaemia (DCI) in SAH. Inflammatory processes may also contribute to DCI, a complication which is the major cause of mortality in SAH (Allan et al., 2005; Chaichana et al., 2009). DCI occurs 4–10 days post-bleed, therefore affording the opportunity for the prophylactic treatment of patients. In these patients, IL-1RA concentrations may be maintained in plasma/CSF/brain at sufficient levels to have a protective effect at the onset of ischaemia, without the need for an intravenous infusion.

In summary, a single neuroprotective dose of IL-1RA, delivered peripherally in the rat, is readily detected in plasma, CSF and ischaemic brain. The data suggest that CSF concentrations may not be a reliable readout of brain penetration, which in focal ischaemia, only occurs in areas of BBB breakdown. These data are the first to show a potential stroke treatment, IL-1RA, reaches brain tissue via an administration route that is relevant in the clinic. Although we did not attempt to dissect the contribution of central/peripheral inflammation to stroke outcome here, we showed that exclusion of IL-1RA from the brain should not be a concern in its clinical development.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Integrative Mammalian Biology initiative and the Medical Research Council.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- IL-1

interleukin-1

- IL-1RA

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist

- IL-1R1

IL-1 receptor I

- MCAo

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- SAH

subarachnoid haemorrhage

Conflict of interest

N.J.R. is a non-executive director of AstraZeneca, but there was no involvement of the company in any of these studies.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC) Br J Pharmacol. (3rd) 2008;153 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan SM, Tyrrell PJ, Rothwell NJ. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:629–640. doi: 10.1038/nri1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks W, Kastin A, Broadwell R. Passage of cytokines across the blood–brain barrier. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1995;2:241–248. doi: 10.1159/000097202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belayev L, Busto R, Zhao W, Ginsberg MD. Quantitative evaluation of blood–brain barrier permeability following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Res. 1996;739:88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes-Silva M, Anthony DC, Issekutz AC, Perry VH. Recruitment of neutrophils across the blood–brain barrier: the role of E- and P-selectins. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1115–1124. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaichana KL, Pradilla G, Huang J, Tamargo RJ. Role of inflammation (leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions) in vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2009.05.027. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KZ, Dale VQ, Denes A, Bennett G, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM, et al. A rapid and transient peripheral inflammatory response precedes brain inflammation after experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1764–1768. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SR, McMahon CJ, Gueorguieva I, Rowland M, Scarth S, Georgiou R, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist penetrates human brain at experimentally therapeutic concentrations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:387–394. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denes A, Ferenczi S, Halasz J, Kornyei Z, Kovacs KJ. Role of CX3CR1 (fractalkine receptor) in brain damage and inflammation induced by focal cerebral ischemia in mouse. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1707–1721. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnan GA. The 2007 Feinberg lecture: a new road map for neuroprotection. Stroke. 2008;39:242. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.493296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durukan A, Marinkovic I, Strbian D, Pitkonen M, Pedrono E, Soinne L, et al. Post-ischemic blood–brain barrier leakage in rats: one-week follow-up by MRI. Brain Res. 2009;1280:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley HCA, Smith CJ, Georgiou RF, Vail A, Hopkins SJ, Rothwell NJ, et al. A randomised phase II study of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in acute stroke patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:1366–1372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, et al. Update of the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable Preclinical Recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40:2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueorguieva I, Clark SR, McMahon CJ, Scarth S, Rothwell NJ, Tyrell PJ, et al. Pharmacokinetic modelling of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of patients following subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;65:317–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez E, Banks W, Kastin A. Blood-borne interleukin-1 receptor antagonist crosses the blood–brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;55:153–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankey G. Long-term outcome after ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:14–19. doi: 10.1159/000069936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum C, Wilcox C, Arend W, Joslin F, Dripps D, Heimdal P, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist activity of a human interleukin-1 inhibitor. Nature. 1990;343:336–340. doi: 10.1038/343336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Chen C-H, Yang Y-H, Lin R-T, Lin F-C, Liu C-K. Eligibility for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22:423–428. doi: 10.1159/000094994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson PJ, O'Connell MT, Rothwell NJ, Hopkins SJ, Nortje Jr, Carpenter KLH, et al. Inflammation in human brain injury: intracerebral concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1Î2, and their endogenous inhibitor IL-1ra. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1545–1557. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konsman J, Vigues S, Mackerlova L, Bristow A, Blomqvist A. Rat brain vascular distribution of interleukin-1 type-1 receptor immunoreactivity: relationship to patterns of inducible cyclooxygenase expression by peripheral inflammatory stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 2004;472:113–129. doi: 10.1002/cne.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korherr C, Hofmeister R, Wesche H, Falk W. A critical role for interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein in interleukin-1 signaling. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:262–267. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroiwa T, Ting P, Martinez H, Klatzo I. The biphasic opening of the blood–brain barrier to proteins following temporary middle cerebral artery occlusion. Acta Neuropathol. 1985;68:122–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00688633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour L, Kang D-W, Ezzeddine M, Chalela J, Warach S. Early blood–brain barrier disruption in human focal brain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:468–477. doi: 10.1002/ana.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loddick SA, Rothwell NJ. Neuroprotective effects of human recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:932–940. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammatory stimulus potentiates the acute phase and CXC chemokine responses to experimental stroke and exacerbates brain damage via interleukin-1- and neutrophil-dependent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4403–4412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5376-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9451–9462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2674-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl BW, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Systemic infection, inflammation and acute ischemic stroke. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, Fisher M, O'Collins V, Sena ES, Dirnagl U, Bath PMW, et al. Good laboratory practice: preventing introduction of bias at the bench. Stroke. 2009;40:e50–52. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.525386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy NJ, Ross J, Rothwell NJ, Loddick SA. Delayed administration of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protects against transient cerebral ischaemia in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:471–476. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offner H, Subramanian S, Parker SM, Afentoulis ME, Vandenbark AA, Hurn PD. Experimental stroke induces massive, rapid activation of the peripheral immune system. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;26:654–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip M, Benatar M, Fisher M, Savitz SI. Methodological quality of animal studies of neuroprotective agents currently in phase II/III acute ischemic stroke trials. Stroke. 2009;40:577–581. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.524330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai DR, Dittmar MS, Baldaranov D, Heidemann RM, Henning EC, Schuierer G, et al. Cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury in rats[mdash]A 3 T MRI study on biphasic blood–brain barrier opening and the dynamics of edema formation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1846–1855. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CJS, Warburton EA, Menon DK. Human cellular inflammation in the pathology of acute cerebral ischaemia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1476–1484. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiniou C, Kooli E, Joyal J-S, Sapieha P, Sennlaub F, Lahaie I, et al. Interleukin-1 and ischemic brain injury in the newborn: development of a small molecule inhibitor of IL-1 receptor. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:325–333. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relton JK, Martin D, Thompson RC, Russell DA. Peripheral administration of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist inhibits brain damage after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1996;138:206–213. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz S, Fisher M. Future of neuroprotection for acute stroke: in the aftermath of the SAINT trials. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:396–402. doi: 10.1002/ana.21127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch B, Regel JP, Wichert M, Gasser T, Volbracht L, Stolke D. Analysis of intrathecal interleukin-6 as a potential predictive factor for vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:828–836. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255440.21495.80. 810.1227/1201.NEU.0000255440.0000221495.0000255480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner RA, Gibson RM, Rothwell NJ, Pinteaux E, Penny JI. Transport of interleukin-1 across cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1115–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Lipsky BP, Russell C, Ketchem RR, Kirchner J, Hensley K, et al. A central nervous system-restricted isoform of the interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein modulates neuronal responses to interleukin-1. Immunity. 2009;30:817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strbian D, Durukan A, Pitkonen M, Marinkovic I, Tatlisumak E, Pedrono E, et al. The blood–brain barrier is continuously open for several weeks following transient focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2008;153:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers L, Kielty C, Pinteaux E. Adhesion to fibronectin regulates interleukin-1 beta expression in microglial cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;41:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton P, Pinteaux E, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and urokinase plasminogen activator mediate interleukin-1-induced neurotoxicity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;37:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Tang XN, Yenari MA. The inflammatory response in stroke. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warach S, Latour LL. Evidence of reperfusion injury, exacerbated by thrombolytic therapy, in human focal brain ischemia using a novel imaging marker of early blood–brain barrier disruption. Stroke. 2004;35:2659–2661. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000144051.32131.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]