Abstract

Prenylation is a post-translational modification critical for the proper function of multiple physiologically important proteins, including small G-proteins, such as Ras. Methods allowing rapid and selective detection of protein farnesylation and geranylgeranylation are fundamental for the understanding of prenylated protein function and for monitoring efficacy of drugs such as farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs). Although the natural substrates for prenyltransferases are farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, farnesyltransferase has been shown to incorporate isoprenoid analogues into protein substrates. In this study, protein prenyltransferase targets were labeled using anilinogeraniol, the alcohol precursor to the unnatural farnesyl pyrophosphate analogue 8-anilinogeranyl diphosphate in a tagging-via-substrate approach. Antibodies specific for the anilinogeranyl moiety were used to detect the anilinogeranyl-modified proteins. Coupling this highly effective labeling/detection method with two-dimensional electrophoresis and subsequent Western blotting allowed simple, rapid analysis of the complex farnesylated proteome. For example, this method elucidated the differential effects induced by two chemically distinct FTIs, BMS-214,662 and L-778,123. Although both FTIs strongly inhibited farnesylation of many proteins such as Lamins, NAP1L1, N-Ras, and H-Ras, only the dual prenylation inhibitor L-778,123 blocked prenylation of Pex19, RhoB, K-Ras, Cdc42, and Rap1. This snapshot approach has significant advantages over traditional techniques, including radiolabeling, anti-farnesyl antibodies, or mass spectroscopy, and enables dynamic analysis of the farnesylated proteome.

Protein prenylation is an evolutionarily conserved post-translational modification essential for normal cellular activities and has an important role in numerous disorders that afflict humans (1–3), including cancers (4), progeroid syndromes (5), immunological/viral illnesses (6), parasitic diseases (7), and brain pathologies, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer disease, and stroke (8). Farnesyltransferase (FTase)1 and geranylgeranyltransferases I and II (GGTases I and II) catalyze the covalent attachment of either a 15-carbon farnesyl isoprenoid (by FTase) or a 20-carbon geranylgeranyl moiety (by GGTases I and II) through a thioether bond to the side chain of carboxyl-terminal cysteines. The preferred recognition motif for FTase and GGTase I is a carboxyl-terminal CAAX box (where C = cysteine, A = aliphatic amino acid, and X = any amino acid), whereas GGTase II prenylates proteins with carboxyl-terminal CXC, XXCC, or CCXX sequences. Although the X position of CAAX motifs determines whether a protein is a substrate for FTase (X = methionine, serine, cysteine, alanine, threonine, or glutamine) or GGTase I (X = leucine or isoleucine), these two enzymes exhibit some cross-specificity.

The prominent role of Ras proteins in carcinogenesis, with ∼20–30% of all human tumors containing activating RAS mutations (9), was the initial driving force behind the design and use of therapeutic agents to inhibit farnesyltransferase (e.g. farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs)) and thus block the oncogenic activity of Ras proteins. However, it is now clear that many other proteins, in addition to Ras, are farnesylated and thus also targets of FTIs (10).

Many cellular processes are dependent upon protein prenylation, including regulation of nuclear membrane structure (11), proliferation (12), apoptosis (13), differentiation (14), transcription (15), viral defense (6), immune response (16), vesicular trafficking (17), glucose-induced insulin secretion (18), and coupling receptor-activated signal transduction cascades (e.g. Ras-to-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling) (19). Use of proteomics to elucidate differences in prenylated protein patterns between normal and diseased cells (e.g. cancer cells) may lead to discovery of new biomarkers with utility for diagnosis as well as for monitoring disease progression and response to therapy. Additionally, comparison of prenylated proteomes of samples treated with a particular drug (e.g. statins, bisphosphonates, or FTIs) with those of vehicle-treated samples can provide critical information regarding drug specificity and efficacy, including revelation of potential resistance mechanisms.

Although some advances in determining the prenylated proteome have been made, there remains no simple, easily applicable method to routinely detect and monitor the prenylated proteome in diverse cell types. For example, the newly created prenylated protein database is an extraordinarily comprehensive summation of potentially modified proteins but was not designed to provide information concerning the actual expression and post-translational modification of potential prenylation substrates in particular cell types (20).

To develop a simple and rapid method for monitoring the prenylated proteome in cells, we used the recently described anilinogeraniol (AGOH), the alcohol precursor to the unnatural farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) analogue 8-anilinogeranyl diphosphate (AGPP), to metabolically label protein prenylation targets (21). We then refined this approach by separation of total cellular proteins using two-dimensional electrophoresis and Western blotting with an antibody to detect the unnatural anilinogeranyl group, thus revealing the farnesylated proteome in leukemia cells. This allowed identification of even low abundance farnesylated proteins, which are usually difficult to detect without forced overexpression. Specificity of this method to detect farnesylated proteins was validated using two clinically tested farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs). Importantly, this method demonstrated clear differences in the abilities of these chemically distinct FTIs to alter the prenylated proteome of leukemia cells and is therefore a powerful tool to identify drug targets, to validate drug activity/specificity, and to determine proteins resistant to specific compounds. Additionally, our work demonstrates that the prenylated proteomic expression pattern is unique for each leukemia cell line subtype tested, suggesting that a specific pattern may exist for each cancer cell type. Thus, this method has the potential to aid in leukemia cell (and possibly for cancer cells in general) classification and to direct discovery of proteins critical to oncogenesis as well as development of therapeutic options to combat cancer.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells, Antibodies, and Other Reagents

Cell lines, obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell cultures (Braunschweig, Germany), were routinely maintained in RPMI 1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Primary antibodies against H-Ras, K-Ras, N-Ras, RhoB, RhoC, Lamin A/C, Lamin B1/B2, INPP5A, DNAJA2, NAP1L1, Cdc42, Rac1/2, Rap1A/1B, LKB1, Rap1, TC21, Rheb, Cyclin G2, PRL-1–3, Annexin II, R-Ras, and horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-HDJ-2 primary antibodies were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Cheshire, UK). Primary antibodies against Pex19, Rap1A/1B, and Rap2A/2B were from BD Biosciences. Horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse secondary antibodies were from GE Healthcare. AGOH and anti-anilinogeranyl (AG) rabbit sera were prepared as described (21). Primary antibodies against tubulin and mevinolin (lovastatin) were from Sigma. CHAPS was from Bio-Rad. PharmalyteTM pH 3–10 ampholytes were from GE Healthcare. GGTI-2147 was from Merck Biosciences GmbH. FTI BMS-214,662 was a generous gift from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dual prenylation inhibitor L-778,123 (FPTase inhibitor A) was a generous gift from Merck Research Laboratories. Zoledronate was a gift from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland).

AG Protein Labeling and Drug Treatment

To facilitate incorporation of the AG label into FTase target proteins, cells were treated with lovastatin 12 h after the last medium change to deplete the cellular reserves of FPP. Because lovastatin is known to induce apoptosis in some cells, empirical determination of optimal concentrations and incubation times to inhibit FPP production without induction of massive cell death is necessary. We determined the following conditions to be optimal: for HL-60 cells, 10 μm lovastatin (36 h); for NB-4 cells, 2 μm lovastatin (24 h); and for K562 cells, 50 μm (24 h). Following lovastatin pretreatment, cells were harvested and incubated for 1 h in fresh, lovastatin-free medium containing DMSO or farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Again, the optimal FTI concentrations have to be empirically determined, e.g. by proliferation and apoptosis assays (data not shown). For our experiments, BMS-214,662 was used at 0.1 μm for HL-60 and NB-4 cells and 1 μm for K562 cells. L-778,123 was used at 20 μm for HL-60 and NB-4 cells and 50 μm for K562 cells. GGTI-2147 was used at 10.6 μm for NB-4 cells, 17 μm for HL-60 cells, and 26.5 μm for K562 cells. Zoledronate was used at 200 μm for HL-60 and NB-4 cells and 400 μm for K562 cells. After 1 h of drug treatment, DMSO or 20 μm AGOH was added as control or to provide the AG label, respectively, incubated, and harvested at different time intervals ranging from 2 to 36 h. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and stored at −70 °C until use.

To monitor the kinetics of early AG incorporation, cells were treated as above, but instead of FTI/DMSO treatment, cells were immediately treated with 20 μm AGOH after removing lovastatin-containing medium. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and harvested at 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS and stored at −70 °C until use.

IEF

Cells were thawed on ice while sample lysis/rehydration buffer (8.0 m urea, 2% CHAPS, 50 mm DTT, 0.25% (w/v) PharmalyteTM pH 3–10 ampholytes, bromphenol blue (trace)) was equilibrated to room temperature. Cell pellets were resuspended in appropriate volumes of sample lysis/rehydration buffer containing protease inhibitor mixtures (Calbiochem and Roche Applied Science) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were sonicated (two 15-s bursts, 20% amplitude; Bandelin Sonopuls, Bandelin Electronic, Berlin, Germany), and cell debris were removed by centrifugation (30 min at 13,000 × g). Proteins were quantified using a Bradford reagent kit (Bio-Rad) and used for isoelectric focusing.

IPG strips (11 cm, pH 3–10; ImmobilineTM DryStrip, GE Healthcare) were thawed at room temperature, and 200 μl of cell lysate containing 400 μg of protein was pipetted into each channel of the focusing tray, leaving about 1 cm at each end. Care was taken not to introduce bubbles, which may interfere with the even distribution of sample in the strip. For each channel, paper wicks wetted with 8 μl of nanopure water were placed at both ends, covering the wire electrodes. Using forceps, cover sheets were peeled from each IPG strip before placing the strip gel side down onto the sample, taking care not to trap air bubbles beneath the strips. Each strip was covered with 2 ml of mineral oil to prevent evaporation. Trays were placed into the Protean IEF cell (Bio-Rad) and run at 20 °C using the following settings: active rehydration at 50 V for 12 h, 250 V linear for 1 h, 2000 V for 2 h, 5000 V for 2 h; 8000 V for 2 h, and 8000 V for 30,000 V-h. IPG strips were then removed from the focusing tray, held vertically to remove mineral oil, and stored at −70 °C in rehydration trays.

SDS-PAGE

Frozen strips and equilibration buffers were thawed at room temperature. Prior to mounting onto the second dimension gel, IPG strips were equilibrated in two steps. Briefly, IPG strips were submersed in 2 ml of equilibration buffer I (6 m urea, 2% SDS, 0.375 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 20% glycerol, 2% (w/v) DTT) and gently shaken for 10 min on an orbital shaker at slow speed. Equilibration buffer I was decanted away, and IPG strips were submersed in 2 ml of equilibration buffer II (6 m urea, 2% SDS, 0.375 m Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 20% glycerol, 2.5% iodoacetamide) and gently shaken for 10 min on an orbital shaker at slow speed. IPG strips were removed from equilibration buffer II, washed briefly with Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer (25 mm Tris, 192 mm glycine, 0.1% SDS (pH 8.3)), and laid, gel side up, onto the back plate of the 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Gels were held vertically, and overlay agarose (0.5% low melting point agarose in 25 mm Tris, 172 mm glycine, 0.1% SDS, bromphenol blue (trace)) was poured into the IPG well of the gels. IPG strips were carefully pushed into the well adjacent to paper wicks wetted with 10 μl of prestained protein size markers (Fermentas), taking care not to trap air bubbles beneath the strip. Following agarose solidification, proteins were separated in the second dimension by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, gels were used for subsequent Western blotting experiments.

Western Blot Analysis

Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered-saline containing Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 2 h at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated (2 h at room temperature) with polyclonal antiserum containing polyclonal anti-anilinogeranyl antibody (polyAG-Ab) serum at a dilution of 1:2000 (1:1000 for all other primary antibodies) in 5% milk, TBS-T; washed four times (5 min each) with TBS-T; incubated (1 h at room temperature) with donkey anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:5000 in 5% milk, TBS-T; and washed five times (5 min each) with TBS-T. Proteins were detected by chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences).

RESULTS

Tagging Proteins with Anilinogeranyl

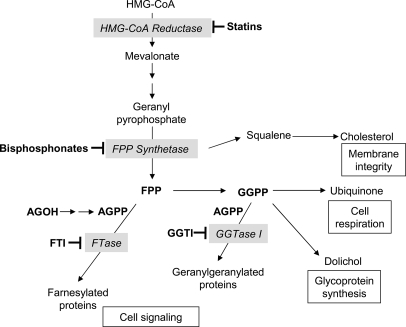

Initially, we investigated the prenylated proteome of three myeloid leukemia cell lines using one-dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis of whole cell lysates harvested following metabolic labeling of prenyltransferase targets using AGOH, the alcohol precursor to the unnatural FPP analogue AGPP, as originally described (21). This method exploits the innate consumption of isoprenoids, including FPP and GGPP, by prenyltransferases, such as FTase and GGTases I and II. FPP and GGPP are produced via the mevalonate pathway, and use of lovastatin to inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, a key enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, is a common method to deplete cellular pools of FPP and GGPP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of mevalonate biosynthetic pathway and its biological functions. Inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase by statins disrupts isoprenoid biosynthesis. Insufficient levels of isoprenoid species (e.g. geranyl pyrophosphate, farnesyl pyrophosphate, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate) cause numerous cellular effects, including loss of membrane integrity due to deficient cholesterol synthesis, altered cell signaling by blockade of post-translational modification of many proteins (e.g. prenylation), etc. Protein post-translational modification can also be blocked by bisphosphonates, FTIs, and GGTIs through inhibition of FPP synthetase, FTase, or GGTase I, respectively. Upon application, AGOH is thought to cross the plasma membrane and act as a substrate for sequential kinase reactions leading to AGPP, which can then be utilized by FTase or possibly also GGTase I to modify cellular proteins.

One-dimensional SDS-PAGE Analysis of Farnesylated Proteome

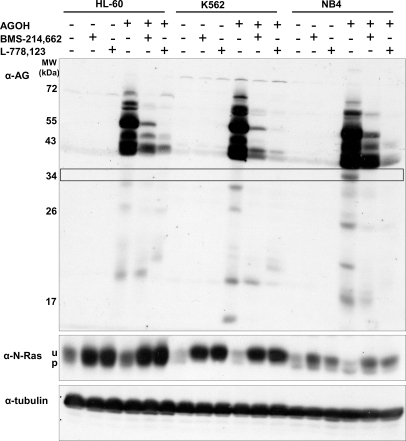

HL-60, K562, and NB-4 myeloid leukemia cells were treated with lovastatin at the indicated concentrations and times, and cells were pelleted and resuspended in fresh medium containing solvent control or FTIs. After 1-h incubation, 20 μm AGOH (the prodrug of AGPP) was added, and cells were incubated an additional 6 h. Cells were harvested and lysed, total cell proteins were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE, and AG-modified proteins were detected by immunoblotting using an antibody directed against AG (Fig. 2). The specificity of this method is demonstrated by the observation of immune specific protein bands in the lanes containing AGOH with limited background in the other lanes. Additionally, the broad size range (17–100 kDa) of specific protein signals correlates well with known prenylated proteins (21, 22). AG-specific signals decreased upon FTI treatment, further substantiating the specificity of this method. Interestingly, this method allows direct evaluation of specific FTI targets as demonstrated by the different efficacies we observed between the two FTIs studied here, BMS-214,662 and L-778,123. This method even allowed identification of subtle differences among the leukemia cell lines tested. For example, there is a prominent AG-labeled protein band with the apparent molecular mass of 34 kDa in NB-4 cells that is missing in HL-60 and K562 cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

One-dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis of AG-modified proteins in presence and absence of farnesyltransferase inhibitors BMS-214,662 and L-778,123. AG labeling of cellular proteins in different myeloid leukemia cell lines was accomplished as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Equal amounts of total cellular proteins were separated by 15% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting using polyAG-Ab serum. α-N-Ras was used to demonstrate cell recovery from lovastatin treatment as well as FTI activity (u, unprenylated form; p, prenylated form), and α-tubulin was used to control for equal loading. Representative immunoblots of two separate experiments (n = 2) are shown. The use of each reagent (AGPP, BMS-214,662, or L-778,123) is indicated by a “+”.

N-Ras-specific immunoblotting demonstrated that AGPP did not inhibit FTase as shown by the similar levels of processed (prenylated) N-Ras in cells treated with AGOH or solvent control. Additionally, FTI activity was demonstrated by the accumulation of unprocessed N-Ras in all FTI-treated cells. Membranes were then reprobed with antibodies raised against tubulin to demonstrate equal protein loading.

Kinetics of AG Tagging Resolved by 2DE Coupled with Western Blotting

A two-dimensional SDS-PAGE approach coupled with immunoblotting was then used to further characterize the individual prenylated proteins contained within the different protein bands identified by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. Total cellular proteins were first resolved on IPG strips by IEF (pH 3–10) and then subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE analysis. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, and AG-labeled proteins were detected by immunoblotting.

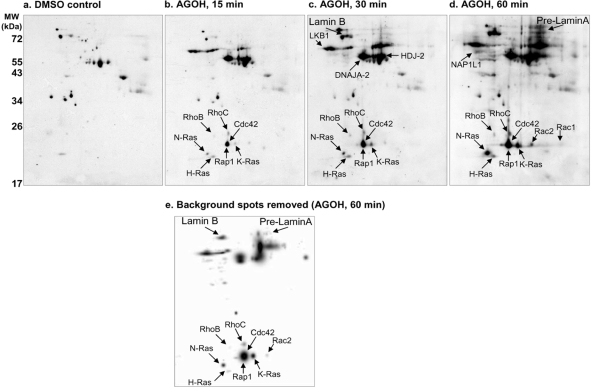

Metabolic labeling of prenylated proteins with AG occurs in a time-dependent manner. Specific signals were detected as early as 15 min following addition of AGOH to cell cultures, and the number and intensity of AG-labeled specific protein spots increased with time (Fig. 3). These results demonstrate that some proteins, such as Cdc42, incorporate the farnesyl analogue more rapidly (as early as 15 min) than other proteins, such as N-Ras, which requires longer incubation with the farnesyl analogue (e.g. ∼60 min) to achieve maximal incorporation. This experiment shows one possible dynamic range this method can be used to monitor. Importantly, the background observed in DMSO control -treated cells (i.e. cells not exposed to AGPP) remained relatively constant throughout these time course experiments (Fig. 3 and data not shown). This background was not unexpected as such large protein quantities (400 μg) were analyzed to increase detection of the smaller prenylation target proteins, many of which are low abundance proteins. Regardless, proteins that incorporated AG were easily discernable from background, and this was especially true for proteins in the lower molecular weight range. Additionally, it was possible to remove these nonspecific background spots using PDQuestTM software to reveal the farnesylated proteome in AGOH-treated HL-60 cells (Fig. 3e).

Fig. 3.

AG labeling of target proteins is time-dependent as demonstrated by 2DE. Cells were treated, and total cellular proteins were harvested at the indicated time points as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Protein identities were assigned to spots by overlaying signals generated using the polyAG-Ab serum with signals generated using specific antibodies for the various proteins labeled in b–d. a, DMSO control; b, 15-min incubation with AGOH; c, 30-min incubation with AGOH; d, 60-min incubation with AGOH. Nonspecific background spots were removed using PDQuest software to reveal the farnesylated proteome in HL-60 cells incubated for 1 h with AGOH (e). Similar results were also observed for NB-4 and K562 cells (data not shown). Representative immunoblots of time courses from two separate experiments are shown (n = 2).

Distinct Prenylated Proteomes Expressed in Different Leukemia Cells

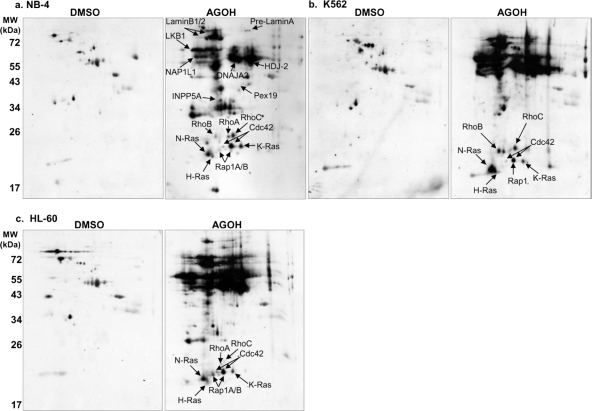

This method provided increased resolution of the prenylated proteome as we were able to detect more than 10 distinct protein spots corresponding to the single band at ∼20 kDa observed by one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4, a–c). The identities of the individual protein spots were determined by overlaying anti-AG immunoblots and immunoblots probed with antibodies specific for different known prenylation target proteins, such as Ras family proteins (supplemental Fig. 1). A list of the proteins we identified using this overlay method is given in Table I. Although specific signals were also observed for Annexin A2, R-Ras, and Rab5A (a GGTase II substrate), these spots did not align with any AG-labeled spots. Also, antibodies against TC21, Rheb, and Cyclin G2 failed to generate specific spots in our experiments.

Fig. 4.

Elucidation of farnesylated proteome by two-dimensional SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Myeloid leukemia cell lines NB-4 (a), K562 (b), and HL-60 (c) were incubated with either DMSO solvent control or 20 μm AGOH (the precursor to AGPP) as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Total cellular proteins were harvested and subjected to 2DE coupled with Western blotting as under “Experimental Procedures.” Protein identities were assigned to spots by overlaying signals generated using the polyAG-Ab serum with signals generated using specific antibodies for the various proteins labeled in a–c. Representative immunoblots are shown (n = 4–6).

Table I. The molecular masses and pI values of the identified farnesylated proteins are given. Unless otherwise referenced, data are from the following sources: Human Intermediate Filament Database, the University of California San Diego-Nature Signaling Gateway, or PhosphoSitePlus. For LKB1, the apparent molecular mass is also given in parentheses. FTI-induced blockade of AG incorporation (i.e. farnesylation) was quantified in NB-4 cells using PDQuest software (standard deviations calculated from three separate experiments are given). The CAAX box motifs and predicted type of prenylation modification predicted by PRENbase (i.e. farnesylation (F) or geranylgeranylation (GG)) are shown (20). ND, not determined due to weak signal. The +++ represents the likelihood that a particular protein is a substrate for farnesylation or geranylgeranylation, with − as least likely and +++ as most likely.

| Protein | Molecular mass (kDa)/pI | Inhibition |

CAAX motif | Predicted |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-778,123 | BMS-214,662 | F | GG | |||

| % | % | |||||

| Prelamin A (23) | 69/6.8–7.2 | 100 ± 0 | 99.5 ± 0.9 | CSIM | ++ | +++ |

| Lamin B1 | 66.4/4.8 | 100 ± 0 | 95.7 ± 5.4 | CAIM | ++ | +++ |

| Lamin B2 | 67.68/5.016 | 94.6 ± 4 | 786.3 ± 13.7 | CYVM | + | + |

| LKB1 | 49.3 (55)/6.4 | 100 ± 0 | 92.6 ± 12.8 | CKQQ | + | − |

| INPP5A | 48.8/6.58 | Not inhibited | Not inhibited | CVVQ | ++ | − |

| DNAJA2a | 45.7/6.44 | 85.7 ± 11.6 | 93.5 ± 7.1 | CAHQ | − | − |

| NAP1L1 | 45.3/4.55 | 100 ± 0 | 99.6 ± 0.4 | CKQQ | + | − |

| HDJ-2 | 44.8/8.8 | 88.5 ± 9.4 | 71.8 ± 17.3 | CQTS | + | − |

| Pex19 | 38/4.26 | 72.0 | Not inhibited | CLIM | ++ | +++ |

| RhoA | 23/5.83 | 88.4 ± 13.2 | 71.3 ± 23.7 | CLVL | ++ | +++ |

| RhoB | 22.1/5.1 | 98.4 | Not inhibited | CKVL | + | + |

| RhoC | 22/6.2 | 9.1 ± 15.7 | 24.9 ± 38.0 | CPIL | + | +++ |

| H-Ras | 21.2/5.16 | 100 ± 0 | 83.9 ± 28.0 | CVLS | ++ | − |

| K-Ras | 21.4/7.64 | 100 ± 0 | Not inhibited | CVIM | +++ | +++ |

| N-Ras | 21.2/5.01 | 100 ± 0 | 73.5 ± 31.1 | CVVM | ++ | ++ |

| Cdc42 | 21.3/6.5 | 98.8 ± 2.1 | 12.9 ± 12.1 | CVLL | ++ | +++ |

| Rac2 | 21.3/7.52 | ND | ND | CSLL | + | ++ |

| Rac1 | 21.2/8.77 | ND | ND | CLLL | + | +++ |

| Rap1A | 20.9/6.39 | 98.8 ± 2.1 | 12.9 ± 12.1 | CLLL | ++ | +++ |

| Rap1B | 20.8/5.65 | 100 ± 0 | 90.3 ± 10.4 | CQLL | + | ++ |

| Rap2A | 20.6/4.55 | ND | ND | CNIQ | + | − |

| Rap2B | 20.5/4.55 | ND | ND | CVIL | ++ | +++ |

a Although the PRENbase algorithm (20) does not predict farnesylation, we and others have observed farnesylation of DNAJA2.

FTI-induced Alteration of Farnesylated Proteome

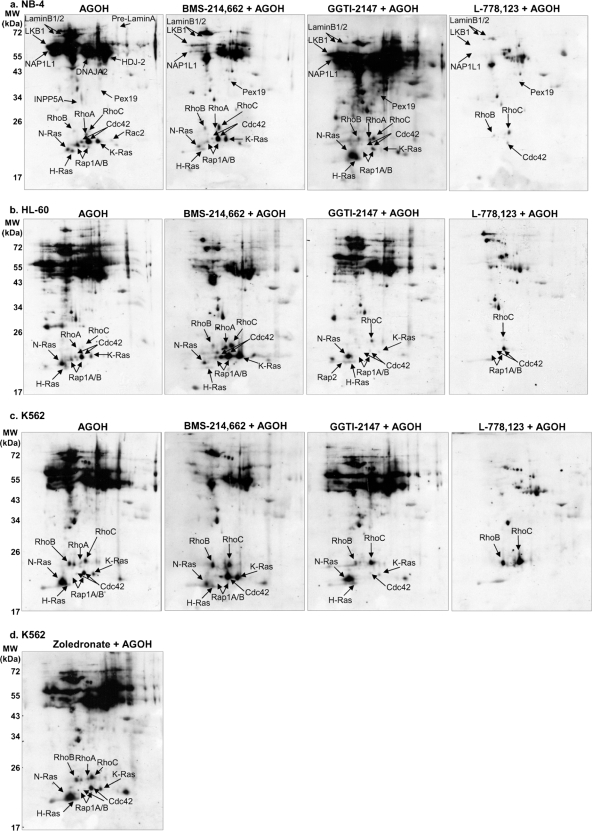

Similarly to the one-dimensional SDS-PAGE results described above, two-dimensional SDS-PAGE analysis of FTI-treated cells demonstrated an overall decrease of AG-labeled spots, thus indicating decreased protein prenylation and demonstrating FTI specificity (Fig. 5, a–c, and Table I). As shown in the blots under the AGOH column, we achieved comprehensive labeling and detection of the prenylated proteome that was easily discernible from nonspecific background spots. Farnesylation of many proteins (e.g. Lamins, NAP1L1, N-Ras, H-Ras, etc.) was strongly blocked by both FTI BMS-214,662 and the dual FTI/geranylgeranyltransferase inhibitor (GGTI) L-778,123. Interestingly, only the dual prenylation inhibitor L-778,123 blocked prenylation of Pex19, RhoB, K-Ras, Cdc42, and Rap1A (Fig. 5, a–c, and Table I), which are predicted to be substrates of both FTase and GGTase I (20). Surprisingly, treatment with FTI BMS-214,662 resulted in increased AG labeling of Cdc42 and K-Ras in HL-60 and K562 cells (Fig. 5, a–c), possibly reflecting their potential cross-specificity for both FTase and GGTase I. The K-Ras CVIM and the Cdc42 CVLL CAAX motifs are substrates for both the FTase and GGTase prenyltransferases, and it appears that GGTase I efficiently catalyzes the transfer of AGPP to CVIM and CVLL in whole cells (Fig. 5, a–c). Modification of some proteins was still detected even in the presence of FTIs, thus suggesting resistance to FTIs under these conditions. To further test this hypothesis, cells were treated with the GGTase I inhibitor GGTI-2147 (Fig. 5, a–c). Our experiments demonstrated that AG modification of some proteins known to be substrates of GGTase I, such as Cdc42, Rap1A, and K-Ras, was blocked by GGTI-2147, whereas modification of N-Ras and Rho proteins was not inhibited by GGTI-2147 (Fig. 5, a–c). In cells treated with a combination of BMS-214,662 and GGTI-2147, the observed blockade of AG modification appeared to be additive (supplemental Fig. 2). That is, cells treated with the combination exhibited reduced levels of AG-labeled Cdc42, Rap1A, and K-Ras in addition to the BMS-214,662-induced pattern. Additional evidence of the specificity of this approach was the observation that the bisphosphonate inhibitor zoledronate did not inhibit protein AG labeling and actually seemed to increase the efficiency of AG incorporation (Fig. 5d and data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Different farnesyltransferase inhibitors elicit distinct alterations of prenylated proteome. NB-4 (a), HL-60 (b), and K562 (c) cells were incubated with DMSO solvent control, FTIs, or GGTI-2147 for 1 h before addition of 20 μm AGOH (or DMSO solvent controls, which are not shown). After exposure to AGOH for 6 h, cells were harvested, and proteins were analyzed by 2DE coupled with Western blotting using polyAG-Ab serum as described under “Experimental Procedures.” d, incorporation of AG was not inhibited by the bisphosphonate zoledronate. Shown here are the results for K562 cells, and similar results were observed in HL-60 and NB-4 cells. Representative immunoblots are shown (n = 3–6).

DISCUSSION

Protein prenylation is critical for the function of many proteins and plays an important role in both normal and pathological cellular activities. Thus, much effort has been invested to increase our understanding of protein prenylation with the aim to exploit this information to develop more efficacious therapeutic regimens. For example, earlier observations that activity of Ras proteins is dependent upon membrane association due to post-translational farnesylation by FTase pioneered the development of FTIs. Although FTIs have demonstrated some clinical activity, results from most trials were not as impressive as initial in vitro data (19). The reasons for the lack of FTI efficacy is unclear; however, it may be related to the fact that many other proteins, in addition to Ras, are farnesylated (10). Furthermore, many FTIs are not entirely specific for FTase but also target GGTases I and II. For example, the proapoptotic activity of several tricyclic BMS FTIs was linked to inhibition of GGTase II (RabGGTase) (24).

A major challenge facing the further development of drugs such as FTIs, statins, and bisphosphonates for more efficacious treatment of human disease is the identification of the protein targets responsible for the drug activities. Because these drugs induce a multitude of effects, it is unlikely that the effects they elicit are due to inhibition of the prenylation of a single protein but rather simultaneous inhibition of protein prenylation of several proteins. The approach we describe above allows a broader analysis of the prenylated proteome than methods currently applied and thus better coverage of the effects a particular treatment regimen has on the prenylated proteome. Our approach allows characterization of changes in protein prenylation induced by drug treatment (e.g. two chemically distinct FTIs (Table I)) as well as description of the distinct prenylated proteome expressed in different cell types (or subtypes), diseases, and organisms.

Earlier studies utilized radiolabeled farnesol and geranylgeraniol, precursors of FPP and GGPP, respectively, to selectively tag FTase and GGTase protein targets (25, 26). Limitations of this approach include the low sensitivity of autoradiographic detection of weak tritium β-emission, which can take several weeks (25). Generation of anti-farnesyl antibodies has been hampered by lack of specificity, for example the inability to distinguish among proteins modified by farnesylation, geranylgeranylation, or other lipids (27).

Tagging proteins with unnatural FPP analogues represents an elegant alternative to the detection of the natural farnesyl moiety (21, 22, 28). Kho et al. (28) and Nguyen et al. (22) developed successful tagging-via-substrate approaches using azidofarnesol/azidofarnesyl diphosphate or biotinylated geraniol for the isolation and detection of farnesylated proteins by mass spectrometry. Nguyen et al. (22) used an elaborate combination of a novel isoprenoid analogue and genetically modified prenyltransferases to analyze the eukaryotic prenylome in cell lysates (in vitro). However, the inherent complexity of mass spectrometry analysis upon which both of these approaches rely makes these methods less accessible to many laboratories. In contrast, Troutman et al. (21) labeled proteins in vivo with AGOH, the prodrug of AGPP, and detected AG-modified proteins with antibodies specific for the AG moiety. Because the structure of the AG moiety is unique with little if any resemblance to known protein modifications, it represents an excellent epitope for selective antibody recognition. Therefore, the anti-AG antibody is ideal for monitoring in vivo prenylation of FTase substrates by Western blotting analysis.

Although AGPP was demonstrated to be highly selective for FTase with limited activity against either GGTase I or squalene synthase (29), AGOH can also be used to monitor the prenylation status of proteins that can be modified by FTase and GGTase I. The ability of farnesyl diphosphate analogues to act as substrates for the prenyltransferases is dependent on both the analogue structure and CAAX sequence (30, 31). The reactivity of analogues also depends on the presence or absence of competing isoprenoid and CAAX substrates (30, 31). The K-Ras CVIM CAAX sequence is a substrate for both the FTase and GGTase prenyltransferases. In vitro, FTase transfers AGPP to CVIM, but it is unknown whether GGTase catalyzes the transfer of AGPP to CVIM. AG incorporation into K-Ras in the presence of FTI BMS-214,662 but not in the presence of GGTI-2147 or the dual inhibitor L-778,123 suggests that GGTase I efficiently catalyzes the transfer of the AG moiety to CVIM in whole cells (Fig. 5, a–c). For example, AG modification of K-Ras and Rap1 could only be blocked by GGTI treatment (Fig. 5), reflecting that both proteins (and to a lesser extent N-Ras) can be either farnesylated or geranylgeranylated (PRENbase). Furthermore, resistance of K-Ras processing to inhibition by FTIs may be due to the higher binding affinity of K-Ras to FTase (32, 33). Others have reported that inhibition of oncogenic K-Ras4B processing required FTI-277 concentrations 100-fold higher than those needed for H-Ras inhibition (34). The reported mean IC50 values of BMS-214,662 for FTase in vitro with H-Ras or K-Ras as protein substrates were 1.3 and 8.4 nm, respectively (35). In contrast, the mean IC50 value of BMS-214,662 for GGTase I with K-Ras as a protein substrate was 1.9–2.3 μm, indicating a 250–1000-fold specificity for FTase. However, the cellular activity of BMS-214,662 in vivo ranged from a mean half-maximal inhibition concentration (EC50) of 0.025 to >2.5 μm, which is similar to the concentrations we used (0.1–1 μm). Reported mean IC50 values of L-778,123 in vitro for FTase and GGTase I using K-Ras peptide as a protein substrate were 2 and 98–100 nm, respectively (36, 37), indicating only a 50-fold specificity for FTase. The mean EC50 for prenylation inhibition in vivo was reported to range from 92 nm to 6.3 μm for HDJ-2 and K-Ras, respectively (37). Although we used slightly higher L-778,123 concentrations (20–50 μm), our incubation times were shorter (6 versus 24 h). Our observations concerning the activity of these two FTIs support the dual enzyme specificity of L-778,123 (Fig. 5).

Interestingly, we observed an accumulation of unprocessed N-Ras in cells treated with FTIs (Fig. 2). This is in agreement with previous reports, which indicate that protein prenylation is critical for proper protein subcellular localization and is a signal for protein turnover/degradation pathways (38–41).

2DE allows a greater resolution of farnesylated proteins as compared with the traditionally used one-dimensional SDS-PAGE. By coupling 2DE with Western blotting using the highly specific anti-AG antibody, we were able to improve detection of the farnesylated proteome, especially in the lower molecular mass range. Thus, we were able to discriminate various farnesylated small G-proteins, including Ras isoforms, Rap1, RhoB, and RhoC as well as larger molecular mass proteins such as Lamins and LKB1. The prenylated proteins we identified cover a large molecular mass range, and the distribution of prenylated proteins detected by this method is similar to that observed by radiolabeling with tritiated farnesol and targeting with azidofarnesol or biotinylated geraniol (22, 26, 28). In contrast to these previous detection methods, the method we describe allows a rapid, simple snapshot analysis of the in vivo farnesylated proteome. Most studies that investigate the effects of FTIs focus on few (and usually only one) protein targets (e.g. HDJ-2). To the best of our knowledge, our report is the most comprehensive characterization of the FTI-induced effects on protein prenylation. Furthermore, this approach allowed distinction of the effects of two different FTIs, thus allowing definition of many of the actual FTI targets. We were unable to use the polyAG-Ab to immunoprecipitate AG-tagged proteins (data not shown); therefore, development of an anti-AG antibody suitable for immunoprecipitation would make this method even more useful.

The simplicity of our approach may greatly accelerate the identification of biomarkers important for disease characterization as well as identification of proteins that are therapeutically relevant for cellular resistance to specific treatment strategies. Thus, this method may aid in creation of more efficacious treatment strategies, including development of drugs with improved and better characterized activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to T. Bunke for superb technical assistance.

* This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM66152 (to H. P. S.). This work was also supported by German José Carreras Leukemia Stiftung Grants DJCLS R 05/21 and DJCLS R 07/32f (to C. R.) and in part by the Kentucky Lung Cancer Research Program (to H. P. S.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- FTase

- farnesyltransferase

- AG

- anilinogeranyl

- AGOH

- anilinogeraniol

- AGPP

- 8-anilinogeranyl diphosphate

- BMS

- Bristol-Myers Squibb

- FPP

- farnesyl pyrophosphate

- FTI

- farnesyltransferase inhibitor

- GGPP

- geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate

- GGTase

- geranylgeranyltransferase

- GGTI

- geranylgeranyltransferase inhibitor

- polyAG-Ab

- polyclonal anti-anilinogeranyl antibody

- TBS-T

- Tris-buffered-saline containing Tween 20

- 2DE

- two-dimensional electrophoresis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang F. L., Casey P. J. (1996) Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu. Rev. Biochem 65, 241–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebti S. M. (2005) Protein farnesylation: implications for normal physiology, malignant transformation, and cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 7, 297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelb M. H., Brunsveld L., Hrycyna C. A., Michaelis S., Tamanoi F., Van Voorhis W. C., Waldmann H. (2006) Therapeutic intervention based on protein prenylation and associated modifications. Nat. Chem. Biol 2, 518–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konstantinopoulos P. A., Karamouzis M. V., Papavassiliou A. G. (2007) Post-translational modifications and regulation of the RAS superfamily of GTPases as anticancer targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 6, 541–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varela I., Pereira S., Ugalde A. P., Navarro C. L., Suárez M. F., Cau P., Cadiñanos J., Osorio F. G., Foray N., Cobo J., de Carlos F., Lévy N., Freije J. M., López-Otín C. (2008) Combined treatment with statins and aminobisphosphonates extends longevity in a mouse model of human premature aging. Nat. Med 14, 767–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bordier B. B., Ohkanda J., Liu P., Lee S. Y., Salazar F. H., Marion P. L., Ohashi K., Meuse L., Kay M. A., Casey J. L., Sebti S. M., Hamilton A. D., Glenn J. S. (2003) In vivo antiviral efficacy of prenylation inhibitors against hepatitis delta virus. J. Clin. Investig 112, 407–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckner F. S., Eastman R. T., Yokoyama K., Gelb M. H., Van Voorhis W. C. (2005) Protein farnesyl transferase inhibitors for the treatment of malaria and African trypanosomiasis. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 6, 791–797 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zipp F., Waiczies S., Aktas O., Neuhaus O., Hemmer B., Schraven B., Nitsch R., Hartung H. P. (2007) Impact of HMG-CoA reductase inhibition on brain pathology. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 28, 342–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bos J. L. (1989) ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res 49, 4682–4689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamanoi F., Kato-Stankiewicz J., Jiang C., Machado I., Thapar N. (2001) Farnesylated proteins and cell cycle progression. J. Cell. Biochem. Suppl 37, 64–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lutz R. J., Trujillo M. A., Denham K. S., Wenger L., Sinensky M. (1992) Nucleoplasmic localization of prelamin A: implications for prenylation-dependent lamin A assembly into the nuclear lamina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 89, 3000–3004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sepp-Lorenzino L., Rao S., Coleman P. S. (1991) Cell-cycle-dependent, differential prenylation of proteins. Eur. J. Biochem 200, 579–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pérez-Sala D., Mollinedo F. (1994) Inhibition of isoprenoid biosynthesis induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic HL-60 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 199, 1209–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunn S. E., Youssef S., Goldstein M. J., Prod'homme T., Weber M. S., Zamvil S. S., Steinman L. (2006) Isoprenoids determine Th1/Th2 fate in pathogenic T cells, providing a mechanism of modulation of autoimmunity by atorvastatin. J. Exp. Med 203, 401–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimster-Denk D., Schafer W. R., Rine J. (1995) Control of RAS mRNA level by the mevalonate pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 59–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood J., Steinman L., Zamvil S. S. (2006) Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6, 358–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coxon F. P., Taylor A. (2008) Vesicular trafficking in osteoclasts. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 19, 424–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kowluru A. (2008) Protein prenylation in glucose-induced insulin secretion from the pancreatic islet beta cell: a perspective. J. Cell. Mol. Med 12, 164–173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan M. A., Ganser A., Reuter C. W. (2007) Targeting the RAS signalling pathway in malignant hematologic diseases. Curr. Drug Targets 8, 217–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurer-Stroh S., Koranda M., Benetka W., Schneider G., Sirota F. L., Eisenhaber F. (2007) Towards complete sets of farnesylated and geranylgeranylated proteins. PLoS Comput. Biol 3, e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troutman J. M., Roberts M. J., Andres D. A., Spielmann H. P. (2005) Tools to analyze protein farnesylation in cells. Bioconjug. Chem 16, 1209–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen U. T., Guo Z., Delon C., Wu Y., Deraeve C., Fränzel B., Bon R. S., Blankenfeldt W., Goody R. S., Waldmann H., Wolters D., Alexandrov K. (2009) Analysis of the eukaryotic prenylome by isoprenoid affinity tagging. Nat. Chem. Biol 5, 227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebel S., Lampron C., Royal A., Raymond Y. (1987) Lamins A and C appear during retinoic acid-induced differentiation of mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol 105, 1099–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lackner M. R., Kindt R. M., Carroll P. M., Brown K., Cancilla M. R., Chen C., de Silva H., Franke Y., Guan B., Heuer T., Hung T., Keegan K., Lee J. M., Manne V., O'Brien C., Parry D., Perez-Villar J. J., Reddy R. K., Xiao H., Zhan H., Cockett M., Plowman G., Fitzgerald K., Costa M., Ross-Macdonald P. (2005) Chemical genetics identifies Rab geranylgeranyl transferase as an apoptotic target of farnesyl transferase inhibitors. Cancer Cell 7, 325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andres D. A., Crick D. C., Finlin B. S., Waechter C. J. (1999) Rapid identification of cysteine-linked isoprenyl groups by metabolic labeling with [3H]farnesol and [3H]geranylgeraniol. Methods Mol. Biol 116, 107–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corsini A., Farnsworth C. C., McGeady P., Gelb M. H., Glomset J. A. (1999) Incorporation of radiolabeled prenyl alcohols and their analogs into mammalian cell proteins. A useful tool for studying protein prenylation. Methods Mol. Biol 116, 125–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X. H., Suh D. Y., Call J., Prestwich G. D. (2004) Antigenic prenylated peptide conjugates and polyclonal antibodies to detect protein prenylation. Bioconjug. Chem 15, 270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kho Y., Kim S. C., Jiang C., Barma D., Kwon S. W., Cheng J., Jaunbergs J., Weinbaum C., Tamanoi F., Falck J., Zhao Y. (2004) A tagging-via-substrate technology for detection and proteomics of farnesylated proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 101, 12479–12484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chehade K. A., Andres D. A., Morimoto H., Spielmann H. P. (2000) Design and synthesis of a transferable farnesyl pyrophosphate analogue to Ras by protein farnesyltransferase. J. Org. Chem 65, 3027–3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Troutman J. M., Andres D. A., Spielmann H. P. (2007) Protein farnesyl transferase target selectivity is dependent upon peptide stimulated product release. Biochemistry 46, 11299–11309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troutman J. M., Subramanian T., Andres D. A., Spielmann H. P. (2007) Selective modification of CaaX peptides with ortho-substituted anilinogeranyl lipids by protein farnesyl transferase: competitive substrates and potent inhibitors from a library of farnesyl diphosphate analogues. Biochemistry 46, 11310–11321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.James G., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. (1996) Resistance of K-RasBV12 proteins to farnesyltransferase inhibitors in Rat1 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 93, 4454–4458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang F. L., Kirschmeier P., Carr D., James L., Bond R. W., Wang L., Patton R., Windsor W. T., Syto R., Zhang R., Bishop W. R. (1997) Characterization of Ha-ras, N-ras, Ki-Ras4A, and Ki-Ras4B as in vitro substrates for farnesyl protein transferase and geranylgeranyl protein transferase type I. J. Biol. Chem 272, 10232–10239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lerner E. C., Qian Y., Hamilton A. D., Sebti S. M. (1995) Disruption of oncogenic K-Ras4B processing and signaling by a potent geranylgeranyltransferase I inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem 270, 26770–26773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose W. C., Lee F. Y., Fairchild C. R., Lynch M., Monticello T., Kramer R. A., Manne V. (2001) Preclinical antitumor activity of BMS-214662, a highly apoptotic and novel farnesyltransferase inhibitor. Cancer Res 61, 7507–7517 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber H. E., Robinson R. G., Watkins A., Nahas D. D., Abrams M. T., Buser C. A., Lobell R. B., Patrick D., Anthony N. J., Dinsmore C. J., Graham S. L., Hartman G. D., Lumma W. C., Williams T. M., Heimbrook D. C. (2001) Anions modulate the potency of geranylgeranyl-protein transferase I inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem 276, 24457–24465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobell R. B., Omer C. A., Abrams M. T., Bhimnathwala H. G., Brucker M. J., Buser C. A., Davide J. P., deSolms S. J., Dinsmore C. J., Ellis-Hutchings M. S., Kral A. M., Liu D., Lumma W. C., Machotka S. V., Rands E., Williams T. M., Graham S. L., Hartman G. D., Oliff A. I., Heimbrook D. C., Kohl N. E. (2001) Evaluation of farnesyl:protein transferase and geranylgeranyl:protein transferase inhibitor combinations in preclinical models. Cancer Res 61, 8758–8768 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holstein S. A., Wohlford-Lenane C. L, Hohl R. J. (2002) Isoprenoids influence expression of Ras and Ras-related proteins. Biochemistry 41, 13698–13704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holstein S. A., Wohlford-Lenane C. L., Hohl R. J. (2002) Consequences of mevalonate depletion. Differential transcriptional, translational, and post-translational up-regulation of Ras, Rap1a, RhoA, and RhoB. J. Biol. Chem 277, 10678–10682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamatakis K., Cernuda-Morollón E., Hernández-Perera O., Pérez-Sala D. (2002) Isoprenylation of RhoB is necessary for its degradation. A novel determinant in the complex regulation of RhoB expression by the mevalonate pathway. J. Biol. Chem 277, 49389–49396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morgan M. A., Sebil T., Aydilek E., Peest D., Ganser A., Reuter C. W. (2005) Combining prenylation inhibitors causes synergistic cytotoxicity, apoptosis and disruption of RAS-to-MAP kinase signalling in multiple myeloma cells. Br. J. Haematol 130, 912–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.