Abstract

Purpose

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is curative therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), but its long-term outcomes are not well described. We studied the long-term outcomes of CML patients in first chronic phase who receive an allogeneic HCT.

Patients and Methods

Our study included 2,444 patients who received myeloablative HCT for CML in first chronic phase between 1978 and 1998 and survived in continuous complete remission for at least 5 years (median follow-up, 11 years; range, 5 to 25 years). Donor sources were human leukocyte antigen–matched siblings in 1,692 patients, unrelated donors in 639 patients, and other related donors in 113 patients.

Results

Overall survival rates at 15 years were 88% (95% CI, 86% to 90%) for sibling HCT and 87% (95% CI, 83% to 90%) for unrelated donor HCT. Corresponding cumulative incidences of relapse were 8% (95% CI, 7% to 10%) and 2% (95% CI, 1% to 4%), respectively. The latest relapse was reported 18 years post-HCT. In multivariable analyses, history of chronic graft-versus-host disease increased risks of late overall mortality and nonrelapse mortality but reduced risks of relapse. In comparison with age-, race-, and sex-adjusted normal populations, the mortality of HCT recipients was significantly higher until 14 years post-HCT; thereafter, mortality rates were similar to those of the general population (relative mortality ratio at 15 years, 2.3; 95% CI, 0 to 4.9).

Conclusion

Recipients of allogeneic HCT for CML in first chronic phase who remain in remission for at least 5 years have favorable subsequent long-term survival, and their mortality rates eventually approach those of the general population.

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is curative therapy for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Allogeneic HCT was standard first-line therapy for CML in the past, but it is now reserved for patients who do not achieve a sustained cytogenetic remission or have progressive disease on tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).1–5 Relatively large numbers of patients have undergone allogeneic HCT for CML since the early 1980s, and this treatment modality continues to be a relevant treatment option for many patients with CML. However, long-term outcomes of patients undergoing an allogeneic HCT for CML have not been well described.6–8 To better understand the risks of late mortality and relapse in patients with CML who have successfully undergone transplantation, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of allogeneic HCT recipients with CML in first chronic phase (CP1) who survived in continuous complete remission for 5 years or more after transplantation. We also conducted analyses to compare their mortality rates with those of the general population.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Sources

Data for this study were obtained from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR). The CIBMTR is a research affiliate of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry, the Autologous Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry and the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) and comprises a working group of more than 500 transplantation centers worldwide that voluntarily contribute data on allogeneic and autologous transplantation recipients to a Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee or the NMDP Coordinating Center in Minneapolis. Participating centers register and provide basic information on all consecutive HCTs; compliance is monitored by on-site audits. Detailed demographic, disease, and transplantation characteristics and outcome data are collected on a sample of registered patients, including all unrelated donor HCTs facilitated by the NMDP in the United States. Patients are followed longitudinally, with yearly follow-up. Computerized error checks, physician review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are done so with a waiver of informed consent and in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations as determined by the institutional review board and the Privacy Officer of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Patients

This study included all patients reported to the CIBMTR who had received a first myeloablative allogeneic HCT for CML in CP1 between 1978 and 1998 and had survived in continuous complete remission for 5 years or more from transplantation. Continuous complete remission was defined as absence of hematologic recurrence, cytogenetic recurrence, or initiation of therapy for relapse. Myeloablative conditioning regimens included in our study consisted of any of the following: regimens with total-body irradiation (TBI) doses of ≥ 5 Gy as single fraction or ≥ 8 cGy as multiple fractions, busulfan doses of > 9 mg/kg, or melphalan doses of > 150 mg/m2 given as single agents or in combination with other drugs.9

From the 7,502 recipients of myeloablative allogeneic HCT for CML in CP1 reported to the CIBMTR during the study period, 5,058 (67%) were excluded because they had died (any cause, n = 3,335), had hematologic or cytogenetic recurrence (n = 452), received a second transplantation (n = 226), or were lost to follow-up by the transplantation center (n = 1,042) within 5 years of HCT. One recipient of syngeneic HCT with missing human leukocyte antigen matching information was also excluded. All surviving recipients of unrelated donor HCT included in this analysis were retrospectively contacted, and they provided informed consent for participation in the NMDP research program. Informed consent was waived by the NMDP institutional review board for all deceased recipients. Approximately 10% of surviving patients would not provide consent for use of research data. To adjust for the potential bias introduced by exclusion of nonconsenting surviving patients, a corrective action plan modeling process randomly excluded appropriately the same percentage of deceased patients (n = 2) using a biased coin randomization with exclusion probabilities based on characteristics associated with not providing consent for use of the data in survivors.10

Our final study population consisted of 2,444 patients (Table 1). Donor sources included human leukocyte antigen–identical sibling donors (n = 1,692), unrelated donors (n = 639), and other related donors (n = 113). Median follow-up of survivors was 12 years (range, 5 to 33 years) from diagnosis of CML and 11 years (range, 5 to 25 years) from transplantation; 1,376 (56%) patients had > 10 years and 377 (15%) had > 15 years of follow-up after HCT, respectively. The follow-up completeness index from the time of HCT, which is the ratio of total observed person-time and the potential person-time of follow-up in a study,11 was 91% at 10 years and 80% at 15 years for our cohort.

Table 1.

Patient, Disease, and Transplantation Characteristics

| Characteristic | HLA-Identical Sibling Donors* |

Unrelated Donors and Other Related Donors† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. Evaluable | No. | (%) | Total No. Evaluable | No. | (%) | |

| No. of patients | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| No. of centers | 201 | 142 | ||||

| Patient-related | ||||||

| Age at transplantation, years | 1,692 | |||||

| Median | 35 | 752 | 34 | |||

| Range | 2-59 | 1-58 | ||||

| < 10 | 33 | 2 | 21 | 3 | ||

| 10-19 | 149 | 9 | 72 | 10 | ||

| 20-29 | 400 | 24 | 165 | 22 | ||

| 30-39 | 550 | 33 | 258 | 34 | ||

| 40-49 | 440 | 26 | 197 | 26 | ||

| ≥ 50 | 120 | 7 | 39 | 5 | ||

| Male sex | 1,692 | 959 | 57 | 752 | 425 | 57 |

| Karnofsky score prior to conditioning | 1,670 | 746 | ||||

| 90-100 | 1,515 | 91 | 669 | 90 | ||

| < 90 | 155 | 9 | 77 | 10 | ||

| Recipient race | 1,691 | 752 | ||||

| White | 1,402 | 83 | 679 | 90 | ||

| African American | 52 | 3 | 11 | 1 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islanders | 128 | 8 | 29 | 4 | ||

| Hispanic | 31 | 2 | 20 | 3 | ||

| Native American | 1 | < 1 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Other | 77 | 5 | 9 | 1 | ||

| Country of transplantation center | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| United States | 440 | 26 | 465 | 62 | ||

| Australia | 101 | 6 | 15 | 2 | ||

| Brazil | 68 | 4 | 5 | 1 | ||

| Canada | 103 | 6 | 39 | 5 | ||

| England | 139 | 8 | 44 | 6 | ||

| France | 87 | 5 | 16 | 2 | ||

| Germany | 93 | 5 | 50 | 7 | ||

| Other‡ | 661 | 39 | 118 | 16 | ||

| Disease-related | ||||||

| CML therapy before transplantation | 1,516 | 630 | ||||

| Interferon alpha with or without other | 430 | 29 | 342 | 54 | ||

| Busulfan with or without other | 271 | 18 | 42 | 7 | ||

| Hydroxyurea with or without other | 763 | 50 | 234 | 37 | ||

| Other | 52 | 3 | 12 | 2 | ||

| Time from diagnosis to transplantation, months | 1,692 | 749 | ||||

| < 12 | 1,068 | 63 | 319 | 43 | ||

| ≥ 12 | 624 | 37 | 430 | 57 | ||

| Transplantation-related | ||||||

| Year of transplantation | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| 1978-1989 | 559 | 33 | 81 | 11 | ||

| 1990-1998 | 1,133 | 67 | 671 | 89 | ||

| Degree of HLA matching | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| HLA-identical sibling | 1,692 | 0 | ||||

| Well matched | 0 | 166 | 22 | |||

| Partially matched | 0 | 205 | 27 | |||

| Mismatched | 0 | 316 | 42 | |||

| Unknown | 0 | 65 | 9 | |||

| Donor-recipient sex match | 1,680 | 743 | ||||

| Male-male | 556 | 33 | 290 | 39 | ||

| Male-female | 387 | 23 | 172 | 23 | ||

| Female-male | 396 | 24 | 129 | 17 | ||

| Female-female | 341 | 20 | 152 | 20 | ||

| Donor-recipient CMV match | 1,434 | 686 | ||||

| Donor (+)/recipient (+) | 631 | 44 | 121 | 18 | ||

| Donor (−)/recipient (+) | 210 | 15 | 153 | 22 | ||

| Donor (+)/recipient (−) | 193 | 13 | 114 | 17 | ||

| Donor (−)/recipient (−) | 400 | 28 | 298 | 43 | ||

| Graft source | 1,690 | 746 | ||||

| Bone marrow | 1,590 | 94 | 737 | 99 | ||

| Peripheral blood | 100 | 6 | 9 | 1 | ||

| Conditioning regimen | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| Total body irradiation | 887 | 52 | 597 | 79 | ||

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide | 783 | 46 | 149 | 20 | ||

| Other | 22 | 1 | 6 | 1 | ||

| GVHD prophylaxis | 1,667 | 752 | ||||

| T-cell depletion | 107 | 6 | 91 | 12 | ||

| CSA + MTX ± other | 1,169 | 70 | 559 | 74 | ||

| CSA ± other (not MTX) | 318 | 19 | 34 | 5 | ||

| Other | 73 | 4 | 68 | 9 | ||

| Post-transplantation–related | ||||||

| Acute GVHD (grade ≥ 2) | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| No | 1,099 | 65 | 295 | 39 | ||

| Yes | 593 | 35 | 457 | 61 | ||

| Severity of acute GVHD, grade | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| None | 796 | 47 | 180 | 24 | ||

| 1 | 303 | 18 | 115 | 15 | ||

| 2 | 468 | 28 | 277 | 37 | ||

| 3 | 99 | 6 | 156 | 21 | ||

| 4 | 26 | 2 | 24 | 3 | ||

| Chronic GVHD | 1,690 | 750 | ||||

| No | 703 | 42 | 223 | 30 | ||

| De novo | 571 | 34 | 168 | 22 | ||

| Prior acute GVHD | 416 | 25 | 359 | 48 | ||

| Severity of chronic GVHD | 1,605 | 667 | ||||

| None | 703 | 44 | 223 | 33 | ||

| Mild | 451 | 28 | 169 | 25 | ||

| Moderate | 349 | 22 | 111 | 17 | ||

| Severe | 102 | 6 | 164 | 25 | ||

| Time to chronic GVHD occurrence | 1,654 | 726 | ||||

| No chronic GVHD | 703 | 43 | 223 | 31 | ||

| ≤ 1 year after transplantation | 852 | 52 | 449 | 62 | ||

| > 1 year after transplantation | 99 | 5 | 54 | 7 | ||

| Follow-up, months | 1,566 | 688 | ||||

| Median | 133 | 124 | ||||

| Range§ | 60-303 | 60-231 | ||||

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myelocytic leukemia; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; CMV, cytomegalovirus; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; CSA, cyclosporine; MTX, methotrexate.

Includes 18 patients who received transplantation from identical twin donors.

Includes unrelated donors (n = 639) and other related donors (n = 113).

Other countries include Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, China, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, and Uruguay.

Follow-up completeness index: HLA-identical sibling donors, 91% at 10 years and 79% at 15 years post-transplantation; unrelated/other related donors, 92% at 10 years and 82% at 15 years post-transplantation.

End Points

Primary study end points were overall survival, disease-free survival, relapse, and nonrelapse mortality. Nonrelapse mortality was defined as death during continuous complete remission. For analyses of overall survival, failure was death from any cause; surviving patients were censored at the date of last contact. Disease-free survival was defined as survival without relapse; patients alive without disease were censored at the time of last follow-up. Relapse was defined by the finding of hematologic or cytogenetic recurrence or by the initiation of therapy for recurrence. For the end points of relapse and nonrelapse mortality, relapse and death in continuous complete remission were considered as competing risks while patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. Acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) were classified using standard criteria.12,13

Statistical Analyses

Univariate probabilities of overall survival were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier estimator; the log-rank test was used for univariate comparisons.14 Probabilities of nonrelapse mortality and relapse were calculated by using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks. Estimates of standard error for the survival function were calculated by Greenwood's formula, and 95% CIs were constructed using log-transformed intervals. The survival interval was defined as time from the date of transplantation to the date of death or last contact.

Potential prognostic factors for overall survival, disease-free survival, relapse, and nonrelapse mortality were evaluated in multivariate analyses using Cox proportional hazards regression.15 Multivariate models were built using a stepwise forward selection with a significance level of 0.01. In each model, the assumption of proportional hazards was tested for each variable using a time-dependent covariate.14 First-order interactions of significant covariates were tested. Variables considered in multivariate analyses included age at transplantation, sex, Karnofsky performance score at transplantation, year of transplantation, time from diagnosis to transplantation, pretransplantation therapy, donor type, donor-recipient sex match, cytomegalovirus status of donor and recipient, graft source, conditioning regimen, GVHD prophylaxis, and the history at 5 years of acute and chronic GVHD.

We calculated estimates of relative mortality as described by Andersen and Vaeth,16 taking into account differences among patients with regard to age, sex, race, and nationality using population-based standard mortality tables. Relative mortality with respect to a transplantation recipient is the relative risk of dying at a given time after transplantation as compared with a person of similar age and sex in the general population. Abridged life tables were obtained from the WHO for 1990 for all countries except for the United States where we used the 1990 unabridged life tables (by race, white v non-white) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Relative mortality rates with 95% point-wise CIs that included 1.0 were not considered to indicate a significant difference from the rates in a normal population. Plots for relative excess mortality and their point-wise 95% CIs were constructed and were based on the kernel smoothed estimates with a band width of 2 years using the Epanechnikov kernel.17 All P values are two-sided. All analyses were carried out using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Overall Survival

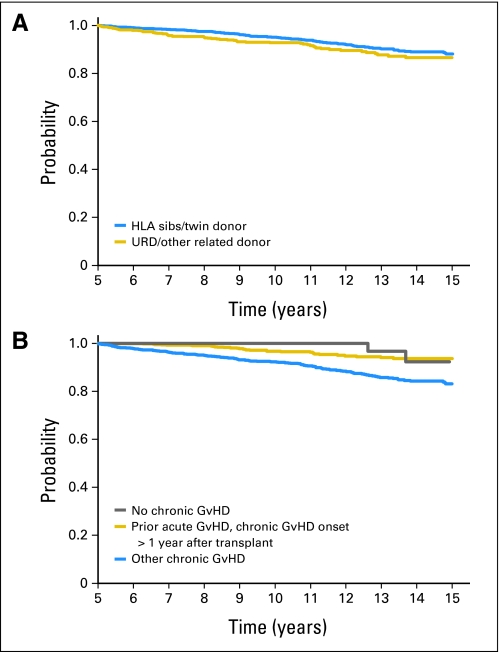

The probability of overall survival for the whole cohort was 94% (95% CI, 92% to 95%) at 10 years and 87% (95% CI, 85% to 89%) at 15 years after HCT and was similar among recipients of sibling donor and unrelated donor grafts (Table 2 and Fig 1). In multivariate analysis, older age at transplantation, use of female donor for a male recipient and use of TBI-based conditioning regimens all independently increased the risk of long-term mortality (Table 3). A history of acute GVHD was also an independent predictor of late mortality, but its effect was time dependent and disappeared after 8 years post-HCT. In addition, a history of chronic GVHD increased the risks of mortality, especially if it occurred within the first year post-transplantation.

Table 2.

Univariate Outcomes of Patients Receiving a Myeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in First Chronic Phase

| Outcome | HLA-Identical Sibling Donors |

Unrelated Donors and Other Related Donors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Evaluable | Probability (%) | 95% CI | No. Evaluable | Probability (%) | 95% CI | |

| No. of patients | 1,692 | 752 | ||||

| Overall survival, years | ||||||

| 10 | 974 | 95 | 94 to 96 | 401 | 93 | 91 to 95 |

| 15 | 296 | 88 | 86 to 90 | 81 | 87 | 83 to 90 |

| Disease-free survival, years | ||||||

| 10 | 929 | 91 | 89 to 92 | 397 | 92 | 90 to 94 |

| 15 | 273 | 83 | 80 to 85 | 79 | 85 | 81 to 88 |

| Relapse, years* | ||||||

| 10 | 929 | 5 | 4 to 6 | 397 | 2 | 1 to 3 |

| 15 | 273 | 8 | 7 to 10 | 79 | 2 | 1 to 4 |

| Nonrelapse mortality, years | ||||||

| 10 | 929 | 4 | 3 to 5 | 397 | 6 | 5 to 8 |

| 15 | 273 | 9 | 7 to 11 | 79 | 13 | 9 to 16 |

NOTE. All patients were alive in continuous complete remission for ≥ 5 years post-transplantation.

Relapse was defined as hematologic recurrence, cytogenetic recurrence, or initiation of therapy for molecular relapse.

Fig 1.

Probability of overall survival by (A) donor source and (B) chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) status. Categories within “other chronic GvHD” include “de novo chronic GvHD, onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation,” “de novo chronic GvHD, onset > 1 year after transplantation,” and “prior acute GvHD, chronic GvHD onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation.” HLA, human leukocyte antigen; URD, unrelated donor.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analyses Comparing Outcomes of Patients Receiving a Myeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in First Chronic Phase

| Variable | No. | Relative Risk* | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | ||||

| Age at transplantation, years | ||||

| < 20 | 249 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| 20-29 | 528 | 1.38 | 0.67 to 2.83 | .39 |

| 30-39 | 760 | 1.84 | 0.94 to 3.61 | .08 |

| 40-49 | 580 | 3.03 | 1.54 to 5.93 | .001 |

| ≥ 50 | 147 | 5.03 | 2.37 to 10.67 | < .001 |

| Donor-recipient sex match | ||||

| Male-male | 777 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| Male-female | 535 | 0.99 | 0.64 to 1.55 | .97 |

| Female-male | 501 | 2.02 | 1.38 to 2.95 | < .001 |

| Female-female | 451 | 1.39 | 0.91 to 2.13 | .13 |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Total body irradiation | 1,368 | 1.00 | .005† | |

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide | 873 | 0.63 | 0.44 to 0.89 | .009 |

| Other | 23 | 2.87 | 0.9 to 9.2 | .08 |

| History of acute GVHD, gradeठ| ||||

| None | 889 | 1.00 | .001† | |

| 1 | 386 | 2.93 | 1.07 to 4.94 | .03 |

| 2 | 700 | 2.36 | 1.09 to 5.1 | .03 |

| 3 | 242 | 4.98 | 2.24 to 11.06 | < .001 |

| 4 | 47 | 5.26 | 1.61 to 17.22 | .006 |

| History of chronic GVHD | ||||

| None | 846 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| De novo, onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation | 583 | 2.54 | 1.62 to 3.96 | < .001 |

| Prior acute GVHD, onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation | 643 | 2.05 | 1.32 to 3.19 | .002 |

| De novo, onset > 1 year after transplantation | 75 | 2.44 | 1.07 to 5.56 | .03 |

| Prior acute GVHD, onset > 1 year after transplantation | 68 | 0.45 | 0.11 to 1.91 | .28 |

| Missing | 49 | 2.11 | 0.74 to 5.99 | .16 |

| Disease-free survival | ||||

| Age at transplantation, years | ||||

| < 20 | 249 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| 20-29 | 528 | 1.96 | 1.08 to 3.54 | .03 |

| 30-39 | 760 | 2.12 | 1.2 to 3.75 | .009 |

| 40-49 | 580 | 2.92 | 1.65 to 5.15 | < .001 |

| ≥ 50 | 147 | 3.93 | 2.06 to 7.51 | < .001 |

| Donor-recipient sex match | ||||

| Male-male | 777 | 1.00 | .02† | |

| Male-female | 535 | 0.89 | 0.62 to 1.27 | .54 |

| Female-male | 501 | 1.49 | 1.09 to 2.05 | .01 |

| Female-female | 451 | 1.08 | 0.76 to 1.54 | .67 |

| History of acute GVHD, gradeठ| ||||

| None | 889 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| 1 | 386 | 10.93 | 6.29 to 19.01 | < .001 |

| 2 | 700 | 8.71 | 5.28 to 14.35 | < .001 |

| 3 | 242 | 23.91 | 14.05 to 40.69 | < .001 |

| 4 | 47 | 21.52 | 7.73 to 59.89 | < .001 |

| Relapse¶ | ||||

| History of chronic GVHD | ||||

| No | 846 | 1.00 | .003 | |

| Yes | 1,418 | 0.56 | 0.38 to 0.82 | |

| Nonrelapse mortality | ||||

| Age at transplantation, years | ||||

| < 20 | 249 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| 20-29 | 528 | 1.47 | 0.66 to 3.31 | .35 |

| 30-39 | 760 | 1.81 | 0.85 to 3.85 | .13 |

| 40-49 | 580 | 2.73 | 1.29 to 5.8 | .009 |

| ≥ 50 | 147 | 4.76 | 2.09 to 10.86 | < .001 |

| Donor-recipient sex match | ||||

| Male-male | 777 | 1.00 | .02† | |

| Male-female | 535 | 0.89 | 0.54 to 1.48 | .65 |

| Female-male | 501 | 1.75 | 1.14 to 2.67 | .002 |

| Female-female | 451 | 1.33 | 0.83 to 2.12 | .23 |

| Conditioning | ||||

| Total body irradiation | 1,368 | 1.00 | .009† | |

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide | 873 | 0.54 | 0.36 to 0.81 | .002 |

| Other | 23 | 1.06 | 0.24 to 4.65 | .94 |

| History of acute GVHD, gradeठ| ||||

| None | 889 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| 1 | 386 | 58.72 | 22.13 to 155.83 | < .001 |

| 2 | 700 | 98.73 | 39.22 to 248.55 | < .001 |

| 3 | 242 | 254.99 | 98.91 to 657.4 | < .001 |

| 4 | 47 | 88.97 | 17.22 to 459.85 | < .001 |

| History of chronic GVHD | ||||

| None | 846 | 1.00 | < .001† | |

| De novo, onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation | 583 | 4.02 | 2.3 to 7 | < .001 |

| Prior acute GVHD, onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation | 643 | 2.67 | 1.57 to 4.53 | < .001 |

| De novo, onset > 1 year after transplantation | 75 | 3.72 | 1.45 to 9.51 | .006 |

| Prior acute GVHD, onset > 1 year after transplantation | 68 | 0.32 | 0.04 to 2.42 | .27 |

| Missing | 49 | 2.97 | 0.99 to 8.92 | .05 |

NOTE. All patients were alive in continuous complete remission for ≥ 5 years post-transplantation.

Abbreviation: GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Relative risk of death, treatment failure, or both.

Overall P values.

Acute GVHD is a time-dependent effect that appears only prior to 8 years post-transplantation.

Effect for years 5-8 post-transplantation.

Relapse was defined as hematologic recurrence, cytogenetic recurrence, or initiation of therapy for relapse.

Disease-Free Survival

Disease-free survival rates at 10 years and 15 years post-HCT were 91% (95% CI, 90% to 92%) and 83% (95% CI, 81% to 85%), respectively. Recipients of sibling and unrelated donor HCT had comparable rates of long-term disease-free survival (Table 2). Older age at transplantation, use of female donor for a male recipient, and acute GVHD history were independent predictors of adverse disease-free survival (Table 3). Similar to overall survival, the effect of acute GVHD was time dependent and was observed only before 8 years after transplantation.

Relapse

The cumulative incidence of relapse for our cohort was 4% (95% CI, 3% to 5%) at 10 years and 7% (95% CI, 5% to 8%) at 15 years after HCT and was higher among recipients of sibling donor HCT than after unrelated donor HCT (Table 2). Latest relapse occurred 18 years after transplantation. In multivariate analyses, chronic GVHD history at 5 years was the only risk factor that was associated with relapse. Compared with patients who did not have chronic GVHD, those with chronic GVHD had 44% lower risk of relapse (Table 3).

Nonrelapse Mortality

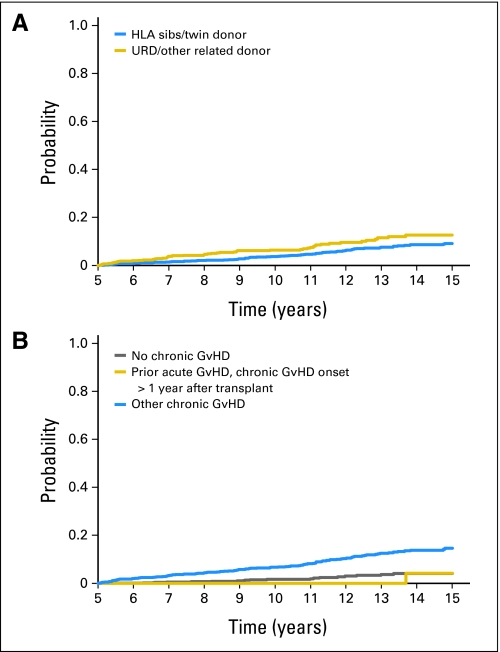

The cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality was 5% (95% CI, 4% to 6%) at 10 years and 10% (95% CI, 9% to 12%) at 15 years after transplantation and was comparable between recipients of sibling and unrelated donor grafts (Table 2 and Fig 2). Older age at HCT, use of a female donor for male recipients, use of TBI-based conditioning regimens, and acute and chronic GVHD history increased the risks of late nonrelapse mortality (Table 3). Acute GVHD again had a time-dependent effect and was not significant beyond 8 years post-HCT.

Fig 2.

Cumulative incidence of nonrelapse mortality by (A) donor source and (B) chronic graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) status. Categories within “other chronic GvHD” include “de novo chronic GvHD, onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation,” “de novo chronic GvHD, onset > 1 year after transplantation,” and “prior acute GvHD, chronic GvHD onset ≤ 1 year after transplantation.” HLA, human leukocyte antigen; URD, unrelated donor.

Causes of Death

The most common cause of death reported by the transplantation centers was organ failure (17%), followed by infection (15%), and GVHD (14%). Disease relapse accounted for 7% and secondary malignancies caused another 7% of all deaths. Cause of death information was missing for 40% (n = 79) of deaths. Causes of death were similar among recipients who received TBI- and non-TBI–based conditioning regimens.

Relative Mortality

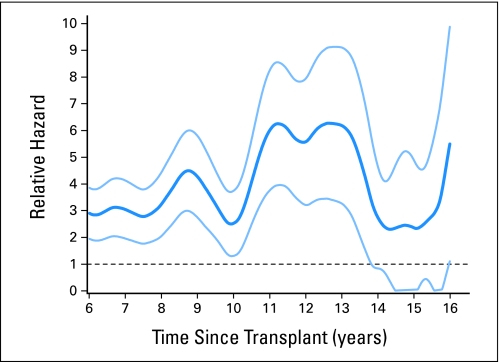

Compared to an age-, sex-, and race-adjusted general population, 5-year survivors of HCT for CML in CP1 were 2.9 times (95% CI, 1.9 to 3.9 times) more likely to die at 6 years and 2.5 times (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.7 times) more likely to die at 10 years after HCT (Fig 3). However, by 15 years after HCT, their relative mortality (2.3; 95% CI, 0 to 4.9) was not significantly different than that of the general population.

Fig 3.

Relative excess mortality (dark blue line) compared with age-, sex-, and race- matched general population for patients surviving in remission for at least 5 years after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant for chronic myeloid leukemia. A relative risk of 1 indicates that the mortality rate of the population of interest is similar to that of the general population. Light blue lines represent 95% CIs.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates the favorable long-term survival of CML patients who receive a myeloablative allogeneic HCT in CP1 and survive for 5 years in remission. However, even in these long-term survivors, there are small but persistent risks of relapse and nonrelapse mortality. Nevertheless, overall mortality rates eventually approached those of the general population.

Long-term outcomes of allogeneic HCT for CML have been previously reported.6–8,18 In general, these studies have shown favorable long-term survival with relapse continuing to be an important cause of late-treatment failures and mortality rates higher than those of the general population. However, these studies had some limitations, such as inclusion of patients with advanced or relapsed disease, the relatively low proportion of patients transplanted with cells from unrelated donors, and the small number of patients with long follow-up. Notable studies include a previous analysis from the CIBMTR7 that described 2,146 patients with CML (80% were in CP1) who had survived in remission for at least 2 years after transplantation. The use of T-cell depleted grafts increased the risks of relapse-related mortality, while prior acute and active chronic GVHD increased the risks of nonrelapse-related deaths. The relative mortality rate was 11.2 (95% CI, 8.2 to 14.1) 5 years after transplantation and 19.1 (95% CI, 8.8 to 29.4) 10 years after transplantation.

Bhatia et al18 have also described late mortality among patients enrolled in the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Among 452 allogeneic HCT recipients with CML who had survived for 2 years, 30% had high-risk disease (> CP1) at HCT and 10% had disease that had relapsed within the first 2 years post-HCT. Only a minority (28%) received transplantations from unrelated donors. Overall survival at 10 years was 79.8%. Older age at transplantation for high-risk disease increased the risks of relapse-related late mortality, while chronic GVHD increased the risks of late nonrelapse mortality. Relative mortality compared with that of the general population was highest in the 2- to 5-year period after allogeneic HCT and then declined dramatically by 15 years. However, mortality rates did not reach those of the general population; the standardized mortality ratio was 8.2 (95% CI, 6.4 to 10.2) for the whole CML cohort and 6.8 (95% CI, 4.9 to 9.1) for patients who had transplantations in CP1.

Copelan et al6 have described a multi-institution experience of outcomes of sibling donor HCT for CML that included 153 patients in CP CML who were leukemia-free at 3 years; the estimated probability of overall survival and leukemia-free survival at 18 years after transplantation was 83% and 67%, respectively. Chronic GVHD decreased the risk of late relapse but not overall or leukemia-free survival. Taken together, the risks of relapse decrease markedly as patients with CML in CP survive longer after allogeneic HCT. However, late relapses are still seen, and these data underscore the importance of continued surveillance, especially with the availability of effective salvage therapies. We did not consider patients with molecular relapse in our analysis and, hence, may have underestimated the true incidence of relapse after HCT. However, our study does raise the intriguing but currently unanswerable question of whether a larger proportion of patients who survive for many years after HCT, apparently free of leukemia, may in fact harbor small numbers of residual leukemia stem cells that are destined in most cases never to manifest themselves in any way. The fact remains that the majority of patients with CML in CP who survive in remission for 2 to 5 years after HCT do appear to have been cured of their leukemia.

The role of allogeneic HCT in CML continues to evolve in the era of TKIs. Allogeneic HCT is no longer considered to be optimal first-line therapy and is now reserved for patients who fail TKI. Whether this strategy of delayed transplantation will increase the risks of late mortality and relapse is not known and will be answered by long-term follow-up of patients subjected to allogeneic HCT in the current decade. Such patients are of course a select group who may have more aggressive leukemia than those who fare much better in the longer term on TKIs. At least in the short term, imatinib exposure before allogeneic HCT does not seem to have any impact on transplantation outcomes.2 The role of TKI in the prevention and treatment of post-HCT relapse also needs to be further investigated.

Despite the limitations of a retrospective cohort study, our analysis highlights the favorable long-term survival among patients with CML in CP1 who receive an allogeneic HCT and survive in continuous complete remission for 5 years after transplantation. Their mortality rates eventually approach those of the general population. However, there continues to be a small but persistent risk of relapse even in these long-term survivors. Chronic GVHD protects against relapse but increases the risks of nonrelapse mortality. Ongoing surveillance of long-term survivors for relapsed disease remains relevant, and data obtained from long-term molecular assessment may answer additional questions regarding late relapse patterns. As in other transplantation indications, survivors of transplantation for CML should be monitored indefinitely to identify late-onset complications, including chronic GVHD, infection, and additional malignancies.19

Acknowledgment

We thank the following companies and organizations for support: Public Health Service Grant No./Cooperative Agreement U24-CA76518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Grant No./Cooperative Agreement 5U01HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; Contract No. HHSH234200637015C with Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; Grants No. N00014-06-1-0704 and N00014-08-1-0058 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from the American Association of Blood Banks; Aetna; American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; Amgen; anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; Baxter International; Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals; Be the Match Foundation; Biogen IDEC; BioMarin Pharmaceutical; Biovitrum AB; BloodCenter of Wisconsin; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Bone Marrow Foundation; Canadian Blood and Marrow Transplant Group; CaridianBCT; Celgene; CellGenix, GmbH; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Children's Leukemia Research Association; ClinImmune Labs; CTI Clinical Trial and Consulting Services; Cubist Pharmaceuticals; Cylex; CytoTherm; DOR BioPharma; Dynal Biotech; Eisai; Enzon Pharmaceuticals; European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation; Gamida Cell; GE Healthcare; Genentech; Genzyme; Histogenetics; HKS Medical Information Systems; Hospira; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Kiadis Pharma; Kirin Brewery; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Merck; Medical College of Wisconsin; MGI Pharma; Michigan Community Blood Centers; Millennium Pharmaceuticals; Miller Pharmacal Group; Milliman USA; Miltenyi Biotec; National Marrow Donor Program; Nature Publishing Group; New York Blood Center; Novartis Oncology; Oncology Nursing Society; Osiris Therapeutics; Otsuka America Pharmaceuticals; Pall Life Sciences; Pfizer; Saladax Biomedical; Schering; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; StemCyte; StemSoft Software; Sysmex America; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries; THERAKOS; Thermogenesis; Vidacare; Vion Pharmaceuticals; ViraCor Laboratories; ViroPharma; and Wellpoint.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or any other agency of the US Government.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: John M. Goldman, Novartis (C), Bristol-Myers Squibb (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: John M. Goldman, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: John M. Goldman, John P. Klein, Kathleen A. Sobocinski, Mary M. Horowitz, J. Douglas Rizzo

Provision of study materials or patients: Mary M. Horowitz

Collection and assembly of data: Zhiwei Wang, Kathleen A. Sobocinski, Mary M. Horowitz, J. Douglas Rizzo

Data analysis and interpretation: Navneet S. Majhail, John P. Klein, Zhiwei Wang, Mary M. Horowitz, J. Douglas Rizzo

Manuscript writing: John M. Goldman, Navneet S. Majhail, Zhiwei Wang, Kathleen A. Sobocinski, Mukta Arora, Mary M. Horowitz, J. Douglas Rizzo

Final approval of manuscript: John M. Goldman, Navneet S. Majhail, John P. Klein, Zhiwei Wang, Kathleen A. Sobocinski, Mukta Arora, Mary M. Horowitz, J. Douglas Rizzo

REFERENCES

- 1.Giralt SA, Arora M, Goldman JM, et al. Impact of imatinib therapy on the use of allogeneic haematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:461–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SJ, Kukreja M, Wang T, et al. Impact of prior imatinib mesylate on the outcome of hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:3500–3507. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-141689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gale RP, Hehlmann R, Zhang MJ, et al. Survival with bone marrow transplantation versus hydroxyurea or interferon for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1998;91:1810–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman JM. How I treat chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era. Blood. 2007;110:2828–2837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-038943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora M, Weisdorf DJ, Spellman SR, et al. HLA-identical sibling compared with 8/8 matched and mismatched unrelated donor bone marrow transplant for chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1644–1652. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.7740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copelan EA, Crilley PA, Szer J, et al. Late mortality and relapse following BuCy2 and HLA-identical sibling marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:851–855. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Socié G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:14–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907013410103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robin M, Guardiola P, Devergie A, et al. A 10-year median follow-up study after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase from HLA-identical sibling donors. Leukemia. 2005;19:1613–1620. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasquini M, Wang Z. Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation 2009: Summary slides Part I. CIBMTR Newsletter. 2009;15:7–11. http://www.cibmtr.org/ReferenceCenter/Newsletters/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farag SS, Bacigalupo A, Eapen M, et al. The effect of KIR ligand incompatibility on the outcome of unrelated donor transplantation: A report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, the European Blood and Marrow Transplant Registry, and the Dutch Registry. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SJ, Klein JP, Barrett AJ, et al. Severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease: Association with treatment-related mortality and relapse. Blood. 2002;100:406–414. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. ed 2. New York, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen PK, Vaeth M. Simple parametric and nonparametric models for excess and relative mortality. Biometrics. 1989;45:523–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramlou-Hansen H. Smoothing counting process intensities by means of kernel functions. Ann Statist. 1983;11:453–466. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: Report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110:3784–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizzo JD, Wingard JR, Tichelli A, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation: Joint recommendations of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research, and the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:138–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]