Abstract

Purpose

To improve the understanding of the appropriate design of phase II oncology clinical trials, we compared error rates in single-arm, historically controlled and randomized, concurrently controlled designs.

Patients and Methods

We simulated error rates of both designs separately from individual patient data from a large colorectal cancer phase III trials and statistical models, which take into account random and systematic variation in historical control data.

Results

In single-arm trials, false-positive error rates (type I error) were 2 to 4 times those projected when modest drift or patient selection effects (eg, 5% absolute shift in control response rate) were included in statistical models. The power of single-arm designs simulated using actual data was highly sensitive to the fraction of patients from treatment centers with high versus low patient volumes, the presence of patient selection effects or temporal drift in response rates, and random small-sample variation in historical controls. Increasing sample size did not correct the over optimism of single-arm studies. Randomized two-arm design conformed to planned error rates.

Conclusion

Variability in historical control success rates, outcome drifts in patient populations over time, and/or patient selection effects can result in inaccurate false-positive and false-negative error rates in single-arm designs, but leave performance of the randomized two-arm design largely unaffected at the cost of 2 to 4 times the sample size compared with single-arm designs. Given a large enough patient pool, the randomized phase II designs provide a more accurate decision for screening agents before phase III testing.

INTRODUCTION

The choice between single-arm, historically controlled and randomized, concurrently controlled designs for phase II oncology clinical trials remains controversial. In practice, most phase II cancer clinical trials use single-arm designs that test null hypotheses based on historical controls.1,2 For the purpose of unbiased estimation of a regimen's activity, patients should theoretically be distributed to treatment regimens in groups otherwise comparable in all respects.3,4 Most objections to randomized phase II trials are related to the increased sample size (2 to 4 times larger than single-arm designs), associated cost, the confidence in accuracy of historical controls, and the use of a concurrent control arm in an exploratory phase II setting.

Overly optimistic results obtained from phase II trials have challenged oncology drug development for years. While acknowledging that negative phase II trials are typically not followed by phase III trials, many promising single-arm phase II cancer trials have yielded negative phase III results in a randomized setting.5–8 Patient selection effects, drifts in treatment success rates over time due to changes in concomitant factors, and small-sample random variation in historical control success rates have all been suggested as contributors to this problem. Even if the patient population in a new trial is identical to that in previous studies, in uncontrolled single-arm phase II trials, the nominal type I error is underestimated by ignoring the variability in historical response rates and other outcomes measures.9,10

Interest in randomized phase II designs is currently increasing as the rising expense and complexity of definitive phase III trials demands the ability of phase II trials to obtain accurate guidance. Randomized phase II trials have been advocated as one solution to the dramatically increasing number of new agents relative to the number of patients available on which to test them.11,12 A simulation study has compared the single-arm design to the randomized two-arm design and concluded that the single-arm design is preferable when only a few patients are available and the historical response rate is well-established, and the randomized two-arm design is preferred when a larger study is possible or the historical response rate is uncertain.13 However, some of the parameters used in the previous simulation were not based on realistic clinical trials. For example, the decision rule threshold for preferring a new agent to a standard regimen ranged from 0% to 5%, while in practice, such small improvement requires very large sample size, and typically a 15% to 20% improvement in the treatment effect is indicative of promising activity.

In this article, we use simulations to investigate the ability of single-arm versus randomized two-arm trials with binary end points to provide accurate conclusions in situations with realistic parameters, when changes in historical outcomes due to patient selection and drift effects are present, or random small sample variability is present independent of the tested therapy. We performed simulations separately using artificial data based on statistical models, as well as individual patient data from a very large colorectal cancer study,14 specifically using the oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFOX) arm of N9741, a large North Central Cancer Treatment Group coordinated clinical trial.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Definitions

Patient temporal drift effect is a systematic, population-wide shift in outcomes, which may be caused by changes in staging, imaging, supportive care, improved surgical or radiation techniques, or for some end points such as overall survival related to more effective second and later-line therapies.

Patient selection effect is a change in the patient population on a trial compared to the population enrolled in historical control trials. A patient selection effect can include changes in the accrual sites (academic v community), or patient mixture in terms of age, performance status, or other factors.

Real Data Simulations

We used individual patient data from N9741 to examine type I error and power estimates in single-arm phase II designs based on small changes in the null hypothesis and in patient baseline characteristics. N9741 demonstrated improved survival for patients who received FOLFOX compared with the standard of care arm (irinotecan plus bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin [IFL]). Six hundred seventy-two eligible patients on the FOLFOX arm were included in this analysis.

Several study designs and end points (Table 1) were selected for the simulations using patient data from the FOLFOX arm. Three end points typically used in phase II trials were considered: tumor response rate, 6-month time-to-progression (TTP) rate, and the 6-month overall survival (OS) rate. The 6-month TTP and OS rates were based on Kaplan-Meier estimates of 6-month event rates from historical studies. The null hypotheses were based on the historical control estimates from the IFL arm in a previous randomized phase III study,15 and from the IFL arm of N9741. The TTP rates from this previous trial were labeled as progression-free survival (PFS) in that manuscript but the definition was more consistent with TTP. We used 1,000 simulated trials of 50 patients each sampled from the FOLFOX arm of N9741 to study the effects of variations in historical control estimates on estimated power.

Table 1.

Study Designs Used for Simulations Based on Data From N974114

| End Point | Study Design | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed response* | |||

| % | 30 v 45 (N9741: 33%) | 35 v 50 (N9741: 33%) | 40 v 55 (Saltz15: 39%) |

| α† | .14 | .12 | .10 |

| β‡ | .13 | .16 | .20 |

| Reject null | 19+§ | 22+ | 25+ |

| 6-month survival rate | |||

| % | 75 v 85 (Saltz: 76%) | 80 v 90 (Saltz: 76%) | 85 v 95 (N9741: 84%) |

| α† | .16 | .10 | .11 |

| β‡ | .21 | .23 | .10 |

| Reject null | 41+ | 44+ | 46+ |

| 6-month progression-free rate | |||

| % | 50 v 65 (Saltz: 53%) | 55 v 70 (Saltz: 53%) | 60 v 75 (N9741: 56%) |

| α† | .10 | .13 | .10 |

| β‡ | .19 | .14 | .16 |

| Reject null | 30+ | 32+ | 35+ |

Defined as two consecutive evaluations with a regression, partial, or complete response.

α observed alpha from simulations.

β observed beta from simulations.

In this design, the null hypothesis is rejected if 19 or greater successes are observed in 50 patients, similarly for other designs.

We also used simulations to study the effect of treating location volume on study power for various study designs and end points. We simulated 1,000 trials of 50 patients each which were randomly sampled from the specific groups of interest from the FOLFOX arm of N9741. For example, if the goal was to simulate the power for a trial where patients were enrolled only from high-volume centers, 1,000 simulated trials of 50 patients each were sampled only from the high-volume centers to represent each of the simulated phase II trials.

Simulations Based on Statistical Models

We compared the single-arm and randomized two-arm phase II designs in terms of their ability to provide accurate conclusions in the presence of variability in the historical control success rate, patient temporal drift, and patient selection effects. We also conducted simulations using parameters designed to mimic actual trials, but without actual patient data. For these simulations we assumed that the historical control success rates follow a beta distribution with two predefined parameters: π0 and W, where π0 is the expectation of success rate for the control regimen θ0 and W is the 90-percent probability interval of the success rate.9 We define π1 to be the expectation of success rate for the experimental regimen, and δ to be the treatment effect for the experimental treatment over the control treatment. The patient temporal drift and selection effects are assumed to follow a normal distribution with a small variance (0.01) and a mean slightly shifted from zero (0.05).

We conducted the simulations under a set of realistic parameters: type I and type II error rates α = β = .1 or .2, the expectation of success rate for the control regimen π0 = 20% or 50%, treatment effect δ = 0, 5%, 10%, 15% or 20%; the 90-percent probability interval for the success rate of the control regimen W = 0.1 or 0.2; the number of historical control studies: 4 or 8 (used to generate the empirical mean of historical control success rates as we specified the expectation π0). We used two-sided one-sample z test (for single arm) or two-sample z test (for randomized two arm) to test if there were significant differences between groups. We also compared the performance of the two designs for various treatment effects when adding historical control variability and patient drift and selection effects separately and jointly.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics on the FOLFOX Arm of N9741

The characteristics of the eligible patients enrolled on the FOLFOX arm of N9741 are presented in Appendix Table A1 (online only). More patients were male (59%), younger than age 65 (61%), and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1 (95%).

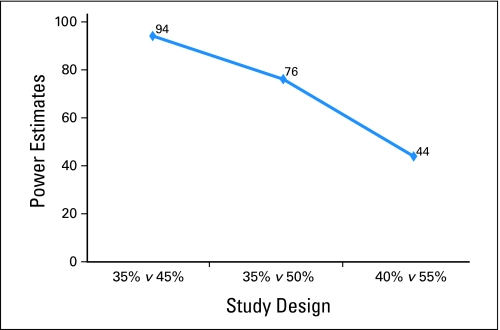

Choice of Null Hypothesis Has Large Impact on Study Conclusions

Figure 1 demonstrates that a clinically small change in the selection of the null hypothesis has a large impact on the study power for the confirmed response end point. If the response rate previously reported for the IFL arm (39%)15 had been used as the null hypothesis for FOLFOX to be compared to in a single arm trial, the power would have been substantially lower than if the correct null hypothesis would have been selected (the N9741 IFL arm had an observed confirmed response rate of 33%). The study power varied from 44% to 94%. Specifically, if FOLFOX had been studied in a single-arm trial using response rate as the end point and an assumed null hypothesis response rate of 40%, only 44% of phase II trials would declare FOLFOX promising. Similar results were observed for the 6-month OS in Appendix Figure A1 (online only) and 6-month TTP in Appendix Figure A2 (online only).

Fig 1.

Choice of null hypothesis has large impact on study conclusions based on single-arm trials of N = 50 drawn from N9741 for confirmed response end point.

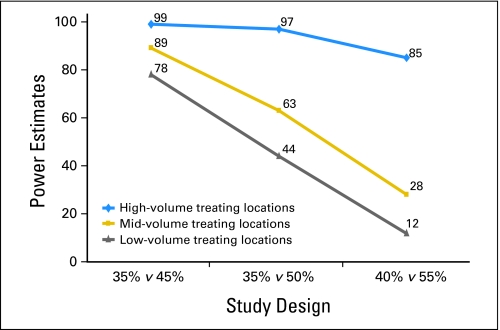

Association of Trial Outcome With Baseline Data

The confirmed response rate on FOLFOX in N9741 was significantly related to treating location volume (trend P = .008), where low-volume treating locations (treated only one patient, total 153 patients), midvolume centers (treated two to four patients, total 288 patients), and high volume centers (treated ≥ five patients, total 231 patients) had confirmed response rates of 42%, 45%, and 55%, respectively. The reasons for this association are unclear and beyond the scope of this work.

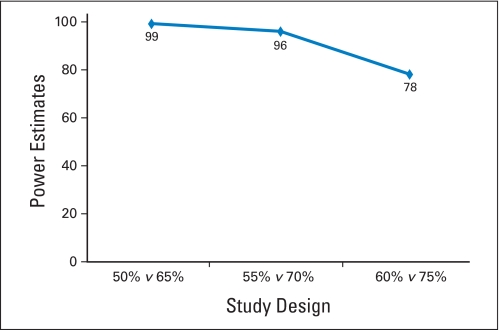

We simulated single-arm trials of FOLFOX with patients drawn from differing mixes of treatment locations. Figure 2 demonstrated that the selection of patients from different treating location volumes greatly influenced the power of the hypothetical phase II trials. Study power varied from 12% to 99%, depending on the choice of null hypothesis and the types of treating locations. If all patients were enrolled at high-volume treating centers, the power was estimated to be much higher than if a study is performed primarily at sites that enroll one to four patients.

Fig 2.

The selection of patients from different treating location volumes influences the trial conclusions. High-volume centers yield high power estimates compared with mid- and low-volume treating locations.

Simulations Based on Statistical Models

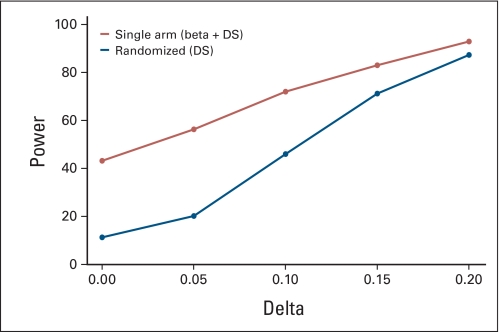

Assuming a fixed historical control success rate and the lack of patient temporal drift or selection effects, both single-arm and randomized two-arm trials correctly estimate false-positive and -negative rates (Appendix Fig A3, online only). However, in the presence of a clinically modest drift effect in the population (5% absolute shift in true control success rate), the false-positive rate in 1,000 simulated single-arm trials is 2 to 4 times higher than the projected error rate, while the randomized design retains the design specifications (Appendix Fig A4, online only). Increasing the sample size in each trial further inflates the false-positive error rate for single arm trials (Appendix Fig A5, online only), as more patients are drawn from a population that differs from the population used to generate the historical control success rates, the results of such a trial will be further biased away from the truth. The results of a complete list of simulation parameters that we used are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

False-Positive and False-Negative Error Rates From 1,000 Simulations Including Both Patient Drift/Selection Effects and Historical Controls Variability

| No. of Historical Control Studies | Single-Arm Trial |

Randomized Two-Arm Trial |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | α | 1 − β | α* | 1 − β* | n | α | 1 − β | α* | 1 − β* | |

| π0 = 0.20, δ = 0.20 | ||||||||||

| W = 0.10 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 21 | .2 | .8 | .47 | .89 | 47 | .2 | .8 | .22 | .78 |

| 40 | .1 | .9 | .46 | .93 | 89 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .87 | |

| 8 | 21 | .2 | .8 | .44 | .89 | 47 | .2 | .8 | .22 | .78 |

| 40 | .1 | .9 | .41 | .95 | 89 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .87 | |

| W = 0.20 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 21 | .2 | .8 | .45 | .88 | 47 | .2 | .8 | .22 | .78 |

| 40 | .1 | .9 | .43 | .93 | 89 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .87 | |

| 8 | 21 | .2 | .8 | .46 | .90 | 47 | .2 | .8 | .22 | .78 |

| 40 | .1 | .9 | .42 | .93 | 89 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .87 | |

| π0 = 0.50, δ = 0.20 | ||||||||||

| W = 0.10 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 26 | .2 | .8 | .39 | .92 | 54 | .2 | .8 | .23 | .83 |

| 48 | .1 | .9 | .44 | .96 | 101 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .91 | |

| 8 | 26 | .2 | .8 | .41 | .94 | 54 | .2 | .8 | .23 | .83 |

| 48 | .1 | .9 | .39 | .98 | 101 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .91 | |

| W = 0.20 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 26 | .2 | .8 | .42 | .93 | 54 | .2 | .8 | .23 | .83 |

| 48 | .1 | .9 | .42 | .95 | 101 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .91 | |

| 8 | 26 | .2 | .8 | .41 | .94 | 54 | .2 | .8 | .23 | .83 |

| 48 | .1 | .9 | .40 | .96 | 101 | .1 | .9 | .11 | .91 | |

NOTE. Sample sizes are estimated from nQuery.

Abbreviations: n, sample size per arm of planned trial; α, design specified alpha; α*, observed alpha from simulations; 1 − β, design specified power; 1 − β*, observed power from simulations; W, width of 90% probability interval of θ0; δ, π1 − π0, the targeted improvement.

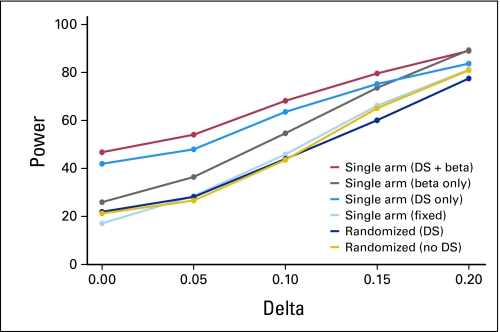

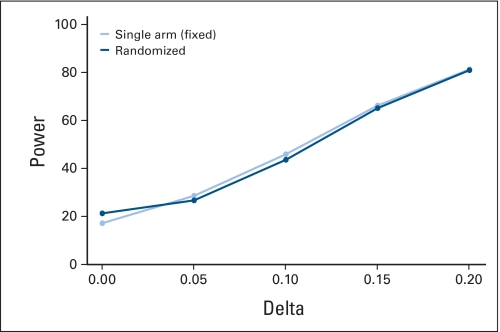

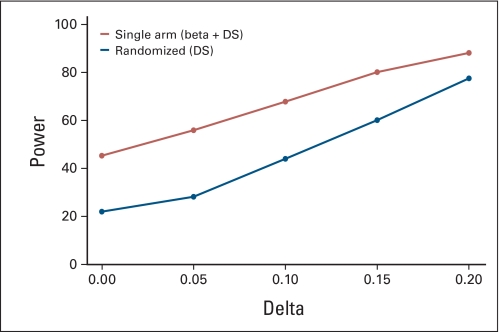

We examined the type I error rates for single-arm designs when various sources of bias are introduced in combination. Figure 3 shows that as multiple sources of variability in the historical control success rates are added sequentially, the error rates in single-arm designs become further biased away from the design specifications. For example, when both drift and selection effects and historical control variability are taken into account, the false-positive error rate in the single-arm design reaches 48%, while the randomized design retains the specified 20%. This is consistent with our findings in real data simulations, ie, the choice of null hypothesis (based on historical studies) has a profound impact on the trial conclusions.

Fig 3.

Error rates under various treatment effects (Delta) when adding sources of bias sequentially. Parameters: α = β = .2. W = 0.1. Four historical controls with mean success rate = 0.2, target success rate = 0.4. n = 21 for single-arm, 47 per arm for randomized trials. DS, drift and selection effects; beta, historical control variability; fixed, fixed historical control rate.

DISCUSSION

When considering the design of phase II oncology trials, two investigator communities must be engaged: the clinical research–oriented oncologist and the biostatistician. In this article, we have presented analyses designed to emphasize elements important to both communities. Through simulations, we have demonstrated the impact of two possible confounding factors that directly influence the interpretation of cancer trial results: modest variability in the success rate of historical controls and modest changes in patient populations between the patients in newer versus older trials. We have demonstrated that both factors can have a profound impact on the type I and II error rates of single-arm trials. In addition to these simulations, we also used data from the established first-line chemotherapy for advanced colorectal cancer, FOLFOX, to demonstrate that if this regimen had been tested in a single-arm phase II trial, it would have been highly likely that further testing of the regimen would not have been recommended. This results from the variability in success rates for key end points even between large trials: when judged against the previously reported response rate of 39% associated with the previous standard regimen IFL from a phase III trial, the observed rate of 45% of FOLFOX in N9741 is not impressive and would have resulted in the rejection of FOLFOX for further testing in 56% of cases. However, when judged against the response rate observed for IFL in N9741 of 33%, the FOLFOX regimen is clearly superior.

In uncontrolled phase II cancer trials, the true type I error rate for the primary end point is in reality unknown and cannot be estimated due to several reasons.16,17 First, the outcomes associated with patients and the methods used to assess the outcomes will change over time due to factors, such as improved supportive care, efficacy of later-line therapies, earlier disease detection, better equipment and technology, and new versions of response assessment criteria (eg, WHO –> RECIST 1.0 –> RECIST 1.1). Second, patient baseline prognostic factors (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, previous treatments, tolerance of adverse events, and unrecognized and therefore unaccountable factors) will inevitably fluctuate between trials, so that the patient population in the new trial differs from the historical controls.18 Third, the interinstitution variability in outcomes is frequently large compared to within-institution variability, and patient outcomes have been repeatedly reported to be associated with institutional characteristics. Fourth, there is intertrial variability in the response rates reported for previous studies of the control regimen, be it a concurrent or historical control.9 Finally, in single-arm trials, ineligible patients and patients who are removed from the study before receiving therapy are typically not included in the analysis, which may lead to overly optimistic results if the sample regimen is taken forward in the same population to a phase III trial where an intent-to-treat analysis will be performed.

Two recent reviews19,20 reported that only 24% to 30% of phase II trials were randomized, with even smaller proportion of randomized two-arm trials with a control group. A main reason is that a randomized phase II trial would normally require 2 to 4 times more patients than a single-arm trial when success is judged based on a comparison to historical controls. For example, in our simulations the randomized two-arm design would require n = 94 to achieve the same theoretical power as the single-arm design with n = 21 (Table 2). This assumes however that the single-arm model is correctly specified, which in practice can never be verified. When patient availability is limited, some authors have proposed a middle ground where the use of historical controls is improved by a model-based prediction based on prognostic factors of the patients in the single-arm phase II trial.21 This model-based phase II design does provide some improvement compared with an unadjusted comparison to historical controls. However, this approach has a weakness inherent to all prediction methods—there is no perfect model which can account for all prognostic factors, therefore the type I and type II error for intertrial variability can only be adjusted to a certain degree; and a model is true only under a series of assumptions, which is not easily extendable to a broader population. Another strategy to handle heterogeneity in sampling from patient groups which differ in prognosis is a stratified phase II design.22 However, this design can only account for his heterogeneity for known stratification factors. When there is an abundance of patients, an alternative to the randomized two-arm design is a multiarm, multistage randomized design, where multiple new therapies are assessed simultaneously against one control arm, futile new therapies are filtered out in early stages and only promising ones remain in the end.23 In the randomized two-arm design, we similarly recommend interim analyses to allow early termination for futility.

Single-arm trials remain appropriate in selected circumstances, such as initial trials to explore toxicity, to demonstrate that a drug hits a biologic target, or for single-agent trials where no alternative exists and response rate is an appropriate end point. However, historical data should be used and referenced carefully. A study has found that nearly half (46%) of phase II trials do not cite the source of their historical response rates, and none implemented designs accounting for differences in prognosis between the historical and the study samples.24 The authors suggested to explicitly refer to historical data “when the null tumor response rate exceeded 10% or when a time-to-event outcome end point such as survival at 1 year was used.” They also suggested the use of statistical methods to adjust for imprecision in historical estimation25 and different patient mix between the historical and the study samples.26

We also stress that randomized phase II studies are not a substitute for phase III trials, they do not provide phase III level type I error control nor power, and the patient cohorts enrolled may still be nonrepresentative for those of an entire population. In addition, when any success in a phase II trial would require making that therapy available to patients, thus impairing the ability to perform a randomized phase III trial, careful consideration of the optimal phase II strategy is required. With these exceptions as noted, we recommend to conduct a randomized phase II trial with a concurrent control to evaluate novel agents in oncology before phase III testing. If desired, randomized phase II studies can be written to transition into phase III studies if they meet their predetermined end points; in such cases this design can be economical in use of patient and monetary resources as well as allowing delays inherent in starting a trial to be encountered once at the outset rather than twice as occurs when sequential phase II and phase III studies are planned. Based on our findings, we concluded that randomization is essential to remove bias and to provide accurate results for further definitive studies.

Appendix

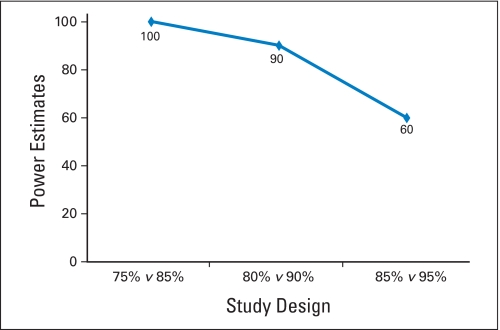

Fig A1.

Choice of null hypothesis has large impact on study conclusions based on single-arm trials of N = 50 drawn from N9741 for 6-month overall survival (OS) rate.

Fig A2.

Choice of null hypothesis has large impact on study conclusions based on single-arm trials of N = 50 drawn from N9741 for 6-month time-to-progression rate.

Fig A3.

Error rates under various treatment effects (Delta) for single-arm v randomized two-arm designs assuming fixed historical control response rate and no drift and selection effects. Parameters: historical control success rate = 0.2, target success rate = 0.4. α = β = 0.2, n = 21 for single-arm trials, n = 47 per arm for randomized two-arm trials. Fixed, fixed historical control rate.

Fig A4.

Error rates when assuming variability in historical controls and patient drift and selection effects. Parameters: 4 historical controls, historical control success rate = 0.2, target success rate = 0.4. W = 0.2. α = β = 0.2, n = 21 for single-arm trials, n = 47 per arm for randomized two-arm trials. Beta, historical control variability; DS, drift and selection effect.

Fig A5.

Similar error rate plots as Appendix Figure A4 with larger sample size. α = β = 0.1, n = 40 for single-arm trials, n = 89 per arm for randomized two-arm trials. W = 0.2. Beta, historical control variability; DS, drift and selection effects.

Table A1.

Patient Characteristics for FOLFOX Arm of N9741 (N = 672)

| Patient Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| < 65 | 410 | 61.1 |

| ≥ 65 | 261 | 38.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 274 | 40.8 |

| Male | 398 | 59.2 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0-1 | 640 | 95.4 |

| 2 | 31 | 4.6 |

| Confirmed response | ||

| No | 350 | 52.1 |

| Yes | 322 | 47.9 |

| Alive at 6 months | ||

| No | 55 | 8.2 |

| Yes | 617 | 91.8 |

| 6-month progression free | ||

| No | 175 | 26.6 |

| Yes | 482 | 73.4 |

| Treating location patient groups | ||

| 1 patient (low) | 153 | 22.8 |

| 2-4 patients (mid) | 288 | 42.9 |

| 5+ patients (high) | 231 | 34.4 |

Abbreviations: FOLFOX, oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil and leucovorin; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Footnotes

Supported by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group Grant No. CA25224 from the National Cancer Institute.

Presented in part at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 29-June 2, 2009, Orlando, FL.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Hui Tang, Daniel J. Sargent

Provision of study materials or patients: Daniel J. Sargent

Collection and assembly of data: Hui Tang, Nathan R. Foster

Data analysis and interpretation: Hui Tang, Nathan R. Foster, Daniel J. Sargent

Manuscript writing: Hui Tang, Daniel J. Sargent

Final approval of manuscript: Hui Tang, Nathan R. Foster, Axel Grothey, Stephen M. Ansell, Richard M. Goldberg, Daniel J. Sargent

REFERENCES

- 1.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green SJ, Dahlberg S. Planned versus attained design in phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 1992;11:853–862. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalmers TC. When should randomisation begin? Lancet. 1968;291:858. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Senn S. Statistical Issues in Drug Development. ed 2. Malden, MA: Wiley-Interscience; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kindler HL, Friberg G, Singh DA, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8033–8040. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.9661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus bevacizumab versus gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: A preliminary analysis of Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):199s. abstr 4508. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiong HQ, Rosenberg A, LoBuglio A, et al. Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor, in combination with gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer: A multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2610–2616. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philip PA, Benedetti J, Fenoglio-Preiser C, et al. Phase III study of gemcitabine [G] plus cetuximab [C] versus gemcitabine in patients [pts] with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma [PC]: SWOG S0205 study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(suppl):199s. abstr LBA4509. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thall PF, Simon R. Incorporating historical control data in planning phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 1990;9:215–228. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams DA. Extra–binomial variation in logistic linear models. Appl Statist. 1982;31:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estey EH, Thall PF. New designs for phase 2 clinical trials. Blood. 2003;102:442–448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein LV, Korn EL, Freidlin B, et al. Design issues of randomized phase II trials and a proposal for phase II screening trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7199–7206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor JM, Braun TM, Li Z. Comparing an experimental agent to a standard agent: Relative merits of a one-arm or randomized two-arm phase II design. Clinical Trials. 2006;3:335–348. doi: 10.1177/1740774506070654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanoff HK, Sargent DJ, Campbell ME, et al. Five-year data and prognostic factor analysis of oxaliplatin and irinotecan combinations for advanced colorectal cancer: N9741. J Clin Oncol. 2008;28:5721–5727. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saltz LB, Cox JV, Blanke C, et al. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:905–914. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009283431302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratain MJ, Sargent DJ. Optimizing the design of phase II oncology trials: The importance of randomization. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubinstein L, Crowley J, Ivy P, et al. Randomized phase II designs. Clinical Cancer Res. 2009;15:1883–1890. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McShane LM, Hunsberger S, Adjei AA. Effective incorporation of biomarkers into phase II trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:1898–1905. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan JK, Ueda SM, Sugiyama VE, et al. Analysis of phase II studies on targeted agents and subsequent phase II trials: What are the predictors for success? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1511–1518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EI-Maraghi RH, Eisenhauer EA. Review of phase II trial designs used in studies of molecular targeted agents: Outcomes and predictors of success in phase III. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1346–1354. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korn EL, Liu PY, Lee SJ, et al. Meta-analysis of phase II cooperative group trials in metastatic stage IV melanoma to determine progression-free and overall survival benchmarks for future phase II trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:527–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.London WB, Chang MN. One- and two-stage designs for stratified phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 2005;24:2597–2611. doi: 10.1002/sim.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parmer MKB, Barthel FMS, Sydes M, et al. Speeding up the evaluation of new agents in cancer. J Natl cancer Inst. 2008;100:1204–1214. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vickers AJ, Ballen V, Scher HI. Setting the bar in phase II trials: The use of historical data for determining “Go/No Go” decision for definitive phase III testing. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:972–976. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazzari M, Heller G, Scher HI. The phase II/III transition: Toward the proof of efficacy in cancer clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:360–368. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazumdar M, Fazzari M, Panageas KS. A standardization method to adjust for the effect of patient selection in phase II clinical trials. Stat Med. 2001;20:883–892. doi: 10.1002/sim.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]