Abstract

Aim

A longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is associated with greater morbidity in the early course of schizophrenia. This formative, hypothesis-generating study explored the effects of stigma, as perceived by family members, on DUP.

Methods

Qualitative interviews were conducted with 12 African American family members directly involved in treatment initiation for a relative with first-episode psychosis. Data analysis relied on a grounded theory approach. A testable model informed by constructs of Link's modified labelling theory was developed.

Results

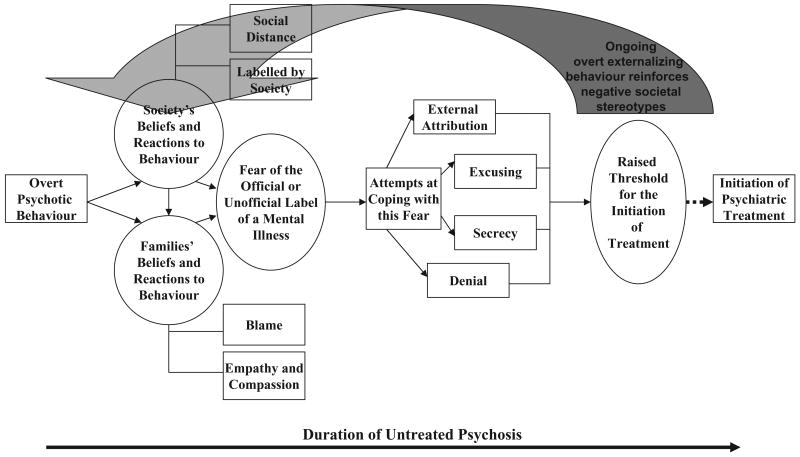

Four main themes were identified, including: (i) society's beliefs about mental illnesses; (ii) families' beliefs about mental illnesses; (iii) fear of the label of a mental illness; and (iv) a raised threshold for the initiation of treatment. A grounded theory model was developed as a schematic representation of the themes and subthemes uncovered in the family members' narratives.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that due to fear of the official label of a mental illness, certain coping mechanisms may be adopted by families, which may result in a raised threshold for treatment initiation, and ultimately treatment delay. If the relationships within the grounded theory model are confirmed by further qualitative and quantitative research, public educational programs could be developed with the aim of reducing this threshold, ultimately decreasing DUP.

Keywords: duration of untreated psychosis, first-episode psychosis, schizophrenia, stigma

Introduction

The interval between the onset of psychosis and the first psychopharmacological treatment, which is commonly termed the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP), is alarmingly protracted.1 A longer DUP is associated with a longer time to symptom remission once treatment is initiated, a lesser degree of recovery, a greater likelihood of relapse and a worse overall outcome.2,3 A large, population-based investigation of first-episode psychosis in the United Kingdom concluded that DUP is at least partly shaped by malleable social factors such as family involvement in help seeking.4 Such social factors are particularly relevant given that family members are often an important part of the individual's social network and are frequently instrumental in initiating and encouraging psychiatric care.5–7

In Scandinavia, a community-based program, the early Treatment and Intervention in Psychosis (TIPS) study, demonstrated that it may be possible to reduce the median DUP.8 TIPS consisted of both educational campaigns aimed at the general population through local media and targeted information for general practitioners, social workers and high school health professionals, as well as early detection teams.9 Research from that project has found that targeted community education10 increases referrals and improves pathways to care in early psychosis.11 The TIPS study did not assess stigma and related attitudes among family members of the first-episode patients, although their informational campaigns clearly were designed in part to enhance community knowledge and reduce misconceptions and stigma.

It should be emphasized that there are real clinical outcomes associated with reducing DUP, as has been demonstrated by TIPS. Melle et al.12 showed that early detection programs that bring patients into treatment earlier – when experiencing a lower level of symptoms – may reduce the risk of suicidality at the time of the first treatment contact. It also has been documented that reducing DUP has effects on negative symptom psychopathology in first-episode schizophrenia.13 Joa et al.9 reported that when the intensive information campaigns were stopped, there was a clear regressive change in help-seeking behaviour, with an increase in median DUP and in baseline symptoms.

Stigma associated with mental illnesses has been cited previously as a social- and family-level factor that contributes to delay in presentation for treatment.14 Beliefs about mental illnesses, and the negative social consequences associated with these conditions, may result in a reluctance to acknowledge mental health problems, which may have direct implications for help-seeking behaviour.15 Despite the potentially critical influence of stigma on treatment initiation in the context of first-episode psychosis, there exists a prominent dearth of research on the interface between stigma and DUP. Compton and Esterberg16 suggested that stigma may increase barriers, which in turn, may result in treatment delays. Similarly, McGorry and Killackey17 maintained that societal stigma and self-stigmatization may act as barriers to treatment initiation for both the individual and his or her family. Given the emerging importance of DUP in relation to secondary prevention efforts for schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, empirical examination of potential determinants of DUP is clearly needed. It is very likely that stigma is one such determinant.

From the inception of the present qualitative study, there were two research questions that were planned a priori to be addressed separately. The first, published by Bergner et al.,18 assessed the family members' broad perspectives on the period of untreated psychosis and general factors potentially associated with treatment delay or treatment initiation. The second, examined in this manuscript, pertained to the potential role of stigma in influencing DUP. In the prior report,18 the investigative team found that family members encountered numerous barriers when seeking treatment, and the narratives generally converged into four themes: (i) misattribution of symptoms or problem behaviours to factors such as depression, drug use and adolescent rebellion; (ii) positive symptoms causing externalizing (outwardly unusual or dangerous) behaviours that served as a catalyst for initiating treatment; (iii) dilemmas related to the personal autonomy of an adult or nearly adult patient; and (iv) system-level factors that may delay treatment seeking, such as perceived unaffordability of health care and inefficiency on the part of health-care providers. The present study aimed to develop a grounded theory regarding a particular postulated determinant of DUP – stigma as perceived by family members. Thus, this study addressed whether family members' qualitative reports of the process of treatment initiation for individuals with first-episode psychosis reveal perceived stigma as a potential factor in treatment delay/DUP. A grounded theory approach facilitated synthesis of themes and subthemes elicited in qualitative interviews and enabled the development of a testable model, which was informed by constructs of modified labelling theory put forth by Link et al.19,20 The resulting model proposes possible ways in which stigma may affect treatment delay, leading to a longer DUP and ultimately poorer outcomes associated with first-episode psychosis.

Methods

Data for the study came from the Atlanta Cohort on the Early course of Schizophrenia project. Research participants included patients hospitalized for a first episode of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, as well as their relatives, who had initiated contact with mental health services. Participants were recruited from two urban, public-sector, inpatient psychiatric units in the south-eastern United States.

The relatives comprised a convenience sample. First-episode patients were asked to refer 1–2 close family members to the project. In-depth interviews were conducted with 12 relatives. Inclusion criteria for family members were: (i) age 18–65 years; (ii) English speaking; and (iii) having had regular recent contact (at least monthly) with the patient. Prior to inception of the study, it was thought that a sample size of 12 participants would provide theoretical saturation. This was in fact found to be the case. A semistructured interview guide assessed family members' perceptions of the stigma associated with mental illnesses and the possible effects of stigma on treatment delay, after broader, more general themes (described in the Bergner et al.18 study) had been elicited. That is, the guide largely utilized open-ended questions to probe for potential determinants of treatment delay, but included a final section that asked more specifically about potential effects of stigma.

The 12 interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Each transcript was reviewed by two independent raters. Both raters were completing a graduate-level degree in public health at the time of the analysis and had received considerable training in qualitative methodology. The textual data were explored inductively using content analysis to generate categories,21 which were then refined into themes and subthemes. Theoretical saturation occurred when no new properties appeared to emerge from the data. The list of recurring themes and subthemes was discussed and compared between the raters to reach a consensus. The themes and subthemes on which there was consensus were included in the results. A rough model using the themes and subthemes was then generated. At this point, the literature on stigma was reviewed, and the investigative team observed that the constructs of modified labelling theory19,20 bared similarity to the framework that had been created, and that this theory could further inform the development of the model. Although the research team did not begin the study with a preconceived hypothesis as to how families' beliefs and actions regarding the stigma of mental illness could affect treatment delay, during the grounded theory/model development process, modified labelling theory seemed particularly informative.

DUP, defined as the number of weeks from the onset of positive psychotic symptoms until first hospital admission, was measured in a systematic manner as described previously.22 Dating the onset of positive psychotic symptoms relied on information from the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia inventory,23 as well as select items from a semistructured interview, the Course of Onset and Relapse Schedule/Topography of Psychotic Episode.24

Results

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 12 relatives of 10 first-episode, first-hospitalization patients with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. All participants were African American. One or two family members represented each patient. Seven mothers, two fathers, one sister, one grandmother and one uncle participated. Ten of the 12 participants lived with the respective patients prior to hospitalization. The mean age of participants was 47.8 ± 7.6 years. Nine had attended college, and nine were currently employed. The annual household income of 10 of the participants was less than 30 000 US$, which is well below the median household income of $50 233 in 2007 reported by the United States Census Bureau.25 Eight of the participants reported a history of a psychiatric illness in their families.

All of the patients were African American and had been diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. The mean age of the patients was 22.0 ± 3.5 years. Seven were male, six had not graduated from high school, none were married and six had been incarcerated previously. In the larger study sample that included 109 hospitalized patients with non-affective first-episode psychosis, the median DUP was 22.3 weeks (range: 0–839). The present subsample's median DUP was 42.4 weeks (range: 2–204), which was not significantly different from the median DUP of the larger sample based on a Mann-Whitney U-test. Inspection of the transcripts revealed that relations between themes did not appear to vary by length of objectively assessed DUP.

The four main themes generated by the data analysis included: (i) society's beliefs about mental illnesses; (ii) families' beliefs about mental illnesses; (iii) fear of the label of a mental illness; and (iv) a raised threshold for the initiation of treatment. Although themes and subthemes were supported by a large number of excerpts across interviews, for concision, only two representative quotations are given below for each theme and one or two for each related subtheme.

Theme 1: society's beliefs about mental illnesses

This theme represents participants' perceptions of society's reaction to the behaviour of their increasingly ill family member. As a whole, society's reactions toward those suffering from a mental illness were noted to be extremely negative. Two participants commented:

Oooh they don't look at 'em good. They think they're a joke. I've seen people laugh at folks and, ya know, make comments and stuff, but society does not have a clue or understand what's going on.

They make a joke of them and laugh at them. They don't give them treatment, they just want to stand there and laugh at them if they do something funny.

Two subthemes – labelling and social distancing – emerged from the data. It appeared that the behaviour of the individual, even before a diagnosis was given, was sufficient to initiate the labelling process, and link the individual to undesirable societal stereotypes. One participant commented:

You know, laypeople, if they think someone has a mental illness they're gonna just label them as crazy.

Initiation of treatment also appeared to be a path by which society would label an individual. For example, one participant noted:

I think when people have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or whatever, they automatically think, ‘He's just gonna do something outrageous.’

In addition to the labelling subtheme, family members perceived that society reacts to an individual with a mental illness by displaying a distinct preference for social distance. This is exemplified by one participant's comments:

They look at them in a different way, ya know. They see something wrong with them. They look at them strange. They don't seem like they want to be around them.

Family members highlighted the fact that their own perspectives differed vastly from those held by society, possibly due to their proximity, both physically and emotionally, to the individual with the emerging illness. One participant noted:

Unless they've dealt with it personally, they think that the person is just crazy and needs to get some help, or they think, ‘Don't fool with them because they are crazy.’ They don't treat them nice, or they don't, ya know, they're not as nice to them as family members who understand what they're going through. I didn't like it because that's my brother, ya know; don't treat him like that.

Theme 2: families' beliefs about mental illnesses

This theme describes family members' responses to the behaviour of their loved ones experiencing early psychosis. In general, family members' reactions were not as negative as society's reactions as perceived by participants. Two family members commented:

I feel sorry for them, um, you can't really go into their mind and see what happened. All of a sudden it just happens. It could have happened to me – normal, and then the next day I just lose my mind.

I just can only imagine, ya know, being in that situation. I was telling my mom the other day, ‘You don't know unless you're walking in that person's shoes.’

The first subtheme to emerge in relation to families' beliefs about mental illnesses was that of empathy and compassion, exemplified by the following:

I feel compassion for 'em; I really do. And I do believe there are issues in their mind. They are big, they are issues, they are issues for them. Ya know, to them it is real, and I don't think any less of them. And your heart kinda goes out to them. You just want them to not feel the way they feel.

The second subtheme pertained to blame, possibly due to the perception that some behaviours demonstrated by the individual were under his or her control. This was exemplified by one participant's comments:

I was seeing it as being lazy. I would say, ‘You don't want to do anything. You started school and then you stopped going, and you had a job.’ And I was thinking it was just him being lazy and not wanting to do anything.

On the other hand, some participants felt that their loved ones carried no responsibility for their condition.

It's not their fault. It's just something that, I guess, they go through or, like they say, it's through genetics, or maybe just something that's happened throughout their lives to where they just break down.

Theme 3: fear of the label of a mental illness

Participants' refrained from labelling their relatives as having a mental illness, and acknowledged that a formal diagnosis would result in an official label, associated with negative stereotypes. Two participants commented:

I guess they think they're different, but they're not. They're people too. They just got some kind of dis – um, no not disease – but some kind of problem.

I didn't want him to think that, ya know, we were trying to tell him that he was crazy or something like that, but just that he needed to talk to someone who could probably explain to him better than I could what he was experiencing.

Participants were aware of the seemingly permanent nature of the stigma associated with the official label of a mental illness, as exemplified by the following:

Stigma to me is something big as far as like it is just embedded in you. You know, it's engraved with something permanent almost. It just traumatizes you.

Due to fear of an official label, relatives adopted at least four coping behaviours: external attribution, excusing, secrecy and denial. First, participants felt a distinct sense of discomfort acknowledging that their relatives suffered from a mental illness, and were more at ease attributing their behaviours to external factors. For example, one participant commented:

All I could think of was that it was due to the head injury because he had said to me a couple of months before that, ‘Mom I'm going crazy in this house.’ I'm not satisfied with the diagnosis that he got, um, psychosis schizophrenia. I don't think that's the problem that he has. Um, I think it's more of, ya know, head injury, and I don't think schizophrenia comes from a head injury.

A second subtheme pertained to mitigating the impact of the patient's behaviour, which is here termed as excusing the behaviour. In order to protect their loved one from harm, participants reported that they would warn those who came into contact with the individual that he or she could behave in bizarre ways. One participant noted:

I didn't mind that they knew because by him just walking off and talking to people they might, ya know, hurt him if they don't know how he is. I would rather them be aware because he might say something and, ya know, some people can jump off the handle, thinking it's intentional.

However, family members also reported that secrecy would protect them and their loved ones from the negative reactions of others. For example, one participant commented:

You really don't want anyone to know because no one wants to be looked at in a different way, as abnormal.You know, something's wrong with that person. Sometimes it's just overwhelming, dealing with them differently.

Another subtheme related to denial. One participant stated:

There was nothing I could really do to try to make him come together, so I kinda ignored it completely. I just forgot about it.

Theme 4: a raised threshold for the initiation of treatment

This theme pertains to the threshold at which family members initiated treatment. Eight of the 12 participants described a high threshold, for example, their family members were only brought into care following confrontation with the police for violent or suicidal behaviour. For example, two participants commented:

I knew she had to hit rock bottom to open up her eyes to some changes that needed to be made. I felt like something was gonna give. I think it just takes something very negative to open up your eyes.

I didn't pay attention, you know, I said, ‘Well, maybe he'll be alright.’ But he wasn't. When the accident happened – ya know, what happened with his little brother and stuff – he was acting up, talking crazy in the parking lot, saying, ‘Mom, I'm not gonna let nobody hurt you.’ He was thinking his brother was trying to hurt me, but his brother wasn't. He was choking his brother like this and he was so heavy, ya know. I tried to get him off of him. It was just awful.

Once the patient demonstrated violent or suicidal behaviour, the coping mechanisms of the family seemed to be overwhelmed, and treatment was initiated. One participant commented:

I hate to say it, but that's the only thing that helped him – when he came up with that gun.

Discussion

Distinctly negative societal stereotypes pertaining to mental illnesses are known to exist.26,27 Once an individual is labelled as having a mental illness, these negative stereotypes are evoked.28 Individuals with mental illnesses are regarded as unpredictable, aggressive, dangerous, unreasonable, of limited intelligence, lacking in self-control and frightening.29 Studies suggest that a relationship exists between these stereotypical beliefs and a preference for social distance.29,30 As the entire sample of the present study was African American, the effects of race, which is associated with its own stigmatizing beliefs, must additionally be considered. It is known that a key characteristic of racial prejudice is an explicit desire to maintain social distance from stigmatized groups.31 In a qualitative study conducted by Hamilton et al.,32 attitudes regarding schizophrenia of a convenience sample of African Americans from the south-eastern United States were explored. The majority of participants believed that symptoms associated with the disease resulted in the affected individual being inherently dangerous and prone to violence. It was postulated by the authors that this view was responsible for the expressed desire for social distance by the participants.

Families and significant others commonly play an integral role in the help-seeking process. Yung and McGorry,33 in their hybrid/interactive model for the psychosis prodrome, suggested that, ‘feedback loops exist as well, with the family responding in certain ways, which in turn affects the individual and so on.’ In a qualitative study by Boydell et al.,34 patients consistently described the extensive influence of significant others in their social network in seeking help for emerging psychotic symptoms. A qualitative study conducted with family members in the north-eastern United States, by Corcoran et al.,35 found that after consulting with a network of relatives, friends and religious leaders, families sought psychiatric help, only as a last resort. In that study, stigma was identified as a major concern that would affect both the individual and the family for the rest of their lives. One mother remarked, for example, ‘The S word – schizophrenia – I'm going to deal with it for the rest of my life.’

In the present study, the families generally reacted toward the individuals with emerging psychosis with empathy and compassion; however, some blamed their loved ones for some of their behaviours. Negative symptoms, which often predominate in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, may be perceived to be within the individual's control, which could result in blame for the condition.36 Having a family history of a mental illness also may shape the family's unique perspectives. In this study, eight of the 12 participants had a family history of a mental illness. Some research suggests that families with other loved ones with schizophrenia are often able to detect symptoms of the disorder more readily than families with a single affected individual.37 However, a family history of a psychiatric disorder is not reliably associated with a shorter delay in treatment initiation for the first psychotic episode. This may be due to tolerance for, and denial of, early psychotic symptoms by the family,38 as previous exposures may have heightened their awareness of the stigma associated with a confirmed diagnosis. Thus, fear of labelling and negative societal stereotypes associated with mental illnesses may have resulted from previous exposure to an individual with a mental illness.

Fear of labelling may result in the adoption of certain coping mechanisms by family members. For example, they may attribute the patient's behaviour to external factors. In the qualitative study by Corcoran et al.,35 families made a wide range of attributions for early behavioural changes and symptoms in the period leading to psychosis, including stress, drugs and the onset of adolescence itself. In the present study, other coping mechanisms that the families employed included excusing, secrecy and denial. Additionally, in a qualitative study of 15 patients with early psychosis, Judge et al.39 identified withdrawal/social isolation and avoiding help as two prominent coping mechanisms employed by patients in response to early psychosis. Boydell et al.40 conducted a qualitative study of youth experiences of psychosis in Canada, and found that early symptoms of psychosis were often ignored and hidden. It has been suggested that keeping the behaviour of the individual a secret is a means of avoiding anticipated rejection.41

Remarkably, eight of the 10 patients related to participants in this study had accessed the mental health system only following contact with the police due to violent or suicidal behaviour. A high threshold for treatment initiation has been found in other qualitative studies of first-episode patients, whereby dangerous behaviour, a crisis or acute escalation of symptom severity appeared to provoke entry into the mental health system.35,39 It appears that the perceived need for services is influenced not merely by the presence of altered experiences and illness symptoms but also by the social contexts and decisions individuals and their families make in response to these symptoms.

Great importance is currently being attached to determining the clinical and social variables that affect DUP. The themes and subthemes that emerged from the present study's rich, qualitative interviews with family members guided a grounded theory that demonstrates potential ways in which the stigma perceived by family members may raise the threshold for initiating treatment, thus delaying treatment initiation. To illustrate how stigma could prolong DUP, a testable model (Fig. 1) was created by combining themes and subthemes from the qualitative data. The generation of the model was further informed by constructs from modified labelling theory,19,20 as put forth by Link et al. This theory provides an explanatory model of the potential mechanisms through which stigma affects outcomes of mental illnesses. It asserts that psychiatric labels are associated with negative societal reactions, which exacerbate the course of the person's disorder. The anticipation of rejection and negative societal reactions may lead to social withdrawal. Thus, individuals and family members may employ several strategies to minimize the impact of these labels, including keeping their diagnosis and treatment a secret, informing others about their situation or withdrawing from social contacts that they perceive as potentially rejecting.42–44 While these coping mechanisms may protect an individual from some forms of personal rejection, they ultimately may be ineffective because labelling and stigma are social, not individual, problems.43

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of potential effects of stigma on duration of untreated psychosis: a grounded theory model informed by modified labelling theory put forth by Link et al.19,20

The data collected in this qualitative study suggest that the initial signs of a mental illness, including early psychotic symptoms, do not receive appropriate attention and early intervention. Treatment was usually accessed only when the individual displayed violent, suicidal or other overt and alarming behaviour. It could be argued that coping mechanisms employed by family members, who are integral in the help-seeking process – including external attribution, excusing the behaviour, secrecy and denial – have the potential to raise the threshold at which treatment is sought. It is in this way that the stigma surrounding mental illnesses, which has been cited previously as a key barrier to treatment seeking,15 may affect treatment delay. As illustrated by the feedback loop in the model (Fig. 1), it is possible that the raised threshold for the initiation of treatment, and the externalizing behaviour displayed by the individual during the period of treatment delay, reinforces negative societal stereotypes. If this threshold were lowered through programmes that reduce stigma, it is possible that, over time, negative stereotypes also may diminish through this secondary route. What is therefore advocated in an effort to lower this threshold is an overall approach to stigma reduction, which would involve programs of advocacy, public education and exposure to persons with mental illnesses through schools and other societal institutions.44

These findings are by no means intended to lay the fault of delays in treatment initiation within families, as there are individual, structural and societal causes for patients not receiving treatment. Although all participants in this study received care in a public-sector health system that provides services regardless of health insurance status or ability to pay, availability and access are obvious concerns that must be continually addressed. Boydell et al.40 examined issues pertaining to mental health-care access for children and youth in rural Canadian communities from the family perspective. Along with stigma, that study identified lack of awareness of the availability of mental health services, cost factors, the necessity of acting as advocate in order to receive mental health services, limited community resources, waiting times and the ‘invisible’ nature of mental illnesses when contrasted against other physical illnesses, as barriers to accessing mental health care. Individual and family factors that have been shown to be associated with a longer DUP include anxiety associated with psychosis and coping styles used by the individual,45 the family's perception of onset,46 families not recognizing psychotic symptoms until they approached a crisis,35 substance use and homelessness,47 poor premorbid adjustment,48 more insidious mode of onset of psychosis4 and severity of negative symptoms.49

As all 12 participants in this study were African American, the constructs of race, cultural mistrust, prejudice and health-care access for minorities in the United States deserve mentioning. Research suggests that in the United States, racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive a lower quality of health care than non-minorities, even when access-related factors, such as patients' insurance status and income, are controlled.50 In the report entitled Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity,51 then Surgeon General David Satcher highlighted the race-, ethnicity- and culture-based disparities in mental health services for African Americans. The underlying root causes of these disparities are complex, and inevitably tied to historic and contemporary inequalities. It has been argued that such inequalities engender cultural mistrust among the African American population, and this cultural mistrust has been shown to predict negative help-seeking attitudes.52 There is research to suggest that black minorities of Caribbean and African origin show more complex and adverse pathways to the hospital, often involving the police.53 Some studies also show that African Americans are more concerned with stigma than other ethnic groups in the United States and are more likely to endorse stigmatizing beliefs regarding people with psychiatric disorders and their families.54,55 African Americans have reported that stigma is a significant treatment barrier in qualitative studies.54,56,57 In a qualitative study conducted with public-sector, African American mental health consumers, the consequences of stigma concerns for these consumers were substantial.58 Most suffered for many years with untreated mental health problems because they avoided, delayed or refused voluntary mental health treatment to avoid the external and internal stigma of being ‘crazy’, and many consumers faced not just disapproval from others but active discouragement from entering or remaining involved in mental health treatment.

Treatment delay appears to be driven by a complex set of intersecting factors. Stigma, which effects discrimination at the individual, institutional and structural levels,59 is undoubtedly one of many such factors. Sociologists have identified legislative activities that are examples of structural stigma as applied to African Americans.60,61 Institutionalized discrimination at various levels may contribute to racial and ethnic health disparities through multiple pathways, including reduced access to high-quality health-care services, as well as economic and social deprivation.62 Indeed, due to the multifaceted nature of stigma, an alternative model to the one proposed in this study could be conceptualized, in which treatment delay would result not only from individual, family and societal beliefs about mental illness, but also from institutionalized stigma. Such a model may provide a more holistic view of the stigma construct, which, by its nature, is multidimensional. The measurement of institutionalized stigma was unfortunately beyond the range of consideration of the present study.

This study had several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample limit generalizability of the findings – data were collected from a relatively homogeneous sample of African American participants with a family member being evaluated in a large, urban, public-sector, inpatient psychiatric unit in the south-eastern United States. Second, stigma is only one of many variables that undoubtedly influence DUP, and the model is therefore by no means a comprehensive depiction of the treatment delay process. Third, because the study was not longitudinal, changes in families' beliefs about mental illnesses over time could not be assessed. Fourth, it should be reiterated that the model generated, based on the four prominent themes – society's beliefs about mental illnesses, families' beliefs about mental illnesses, fear of the label of a mental illness and a raised threshold for the initiation of treatment – is speculative in nature, rather than directly depicting the results. Lastly, the model generated by this study, as well as the suggestion that stigma may delay help seeking, thereby prolonging DUP, should be interpreted with caution. As the study was cross-sectional in nature, only apparent associations among variables can be evaluated and not causal pathways.

Researchers conducting a large, population-based investigation of first-episode psychosis noted as a limitation that data about the effects of stigma on DUP were not obtained, suggesting that this is an important area for further study.4 Future research should attempt to quantify the hypothesized linkages in the grounded theory model developed herein. Once these relationships are clearly understood, public educational programs could be developed, with the aim of reducing the threshold at which treatment is sought, and ultimately decreasing DUP, leading to improved outcomes for individuals affected by these serious mental illnesses. Wong et al.63 found that early in emerging psychotic illnesses, families report helping patients and worrying about them, although their lives are not yet prominently disrupted. Community-level efforts to inform the public about psychotic disorders and reduce the stigma associated with them could plausibly alleviate family burden, and could lower the threshold for the initiation of treatment even before major family disruptions occur, ultimately improving patients' and families' outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to the last author (K23 MH067589).

References

- 1.Sheitman BB, Lieberman JA. The natural history and pathophysiology of treatment resistant schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:143–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones R, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1785–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morgan C, Abdul-Al R, Lappin JM, et al. Clinical and social determinants of duration of untreated psychosis in the ÆSOP first-episode psychosis study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:446–52. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czuchta DM, McCay E. Help-seeking for parents of individuals experiencing a first episode of schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2001;15:159–70. doi: 10.1053/apnu.2001.25415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamble C, Midence K. Schizophrenia family work: mental health nurses delivering an innovative service. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1994;32:13–6. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19941001-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuck I, du Mont P, Evans G, Shupe J. The experience of caring for an adult child with schizophrenia. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1997;11:118–25. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(97)80034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al. Reducing the duration of untreated first-episode psychosis: effects on clinical presentation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;16:143–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joa I, Johannessen JO, Auestad B, et al. The key to reducing duration of untreated first psychosis: information campaigns. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:466–72. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joa I, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, McGlashan TH. Information campaigns: 10 years of experience in the Early Treatment and Intervention in Psychosis (TIPS) study. Psychiatr Ann. 2008;38:512–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannessen JO. Early recognition and intervention: the key to success in the treatment of schizophrenia? Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2001;9:317–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melle I, Johannesen JO, Friis S, et al. Early detection of first episode of schizophrenia and suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:800–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melle I, Larsen TK, Haahr U, et al. Prevention of negative symptom psychopathologies in first-episode schizophrenia: two-year effects of reducing the duration of untreated psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:634–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fink PJ. Stigma and Mental Illness. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wrigley S, Jackson J, Judd F, Komiti A. Role of stigma and attitudes toward help-seeking from a general practitioner for mental health problems in a rural town. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:514–21. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Compton MT, Esterberg ML. Treatment delay in first-episode nonaffective psychosis: a pilot study with African American family members and the theory of planned behavior. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:291–5. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGorry PD, Killackey EJ. Early intervention in psychosis: a new evidence based paradigm. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2002;11:237–47. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00005807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergner E, Leiner AS, Carter T, Franz L, Thompson NJ, Compton MT. The period of untreated psychosis before treatment initiation: a qualitative study of family members' perspectives. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:530–6. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link BG, Struening EL, Cullen FT, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;54:400–23. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Compton MT, Chien VH, Leiner AS, Goulding SM, Weiss PS. Mode of onset of psychosis and family involvement in help-seeking as determinants of duration of untreated psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:975–82. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins DO, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Graham K, Kazmer J, Lieberman JA. Characterizing and dating the onset of symptoms in psychotic illness: the Symptom Onset in Schizophrenia (SOS) inventory. Schizophr Res. 2000;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman RMG, Malla AK. Course of Onset and Relapse Schedule: Interview and Coding Instruction Guide. London, Ontario: Prevention and Early Intervention for Psychosis Program; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S Census Bureau. [30 May 2009];Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States. 2007 Available from URL: http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p60-235.pdf.

- 26.Graves RE, Cassisi JE, Penn DL. Psychophysiological evaluation of stigma towards schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2005;76:317–27. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey S, Howells K. Dangerousness, unpredictability, and the fear of people with schizophrenia. J Forensic Psychiatry. 1995;6:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52:1461–500. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. Violent attacks on public figures by persons suffering from psychiatric disorders: their effect on the social distance towards the mentally ill. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;245:159–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02193089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulze B, Angermeyer MC. Subjective experiences of stigma: a focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:299–312. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettigrew TF, Meertens RW. Subtle and blatant prejudice in Western Europe. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1995;25:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton LA, Aliyu MH, Lyons PD, et al. African-American community attitudes and perceptions toward schizophrenia and medical research: an exploratory study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:353–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boydell KM, Gladstone BM, Volpe T. Understanding help seeking delay in prodrome to first episode psychosis: a secondary analysis of the perspectives of young people. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2006;30:54–60. doi: 10.2975/30.2006.54.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corcoran C, Gerson R, Sills-Shahar R, et al. Trajectory to a first episode of psychosis: a qualitative research study with families. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1:308–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penn DL, Kohlmaier JR, Corrigan PW. Interpersonal factors contributing to the stigma of schizophrenia: social skills, perceived attractiveness, and symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2000;45:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hambrecht M, Häfner H. Sensitivity and specificity of relatives' reports on the early course of schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 1997;30:12–19. doi: 10.1159/000285023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norman RMG, Malla AK, Manchanda RL, Harricharan R, Northcott S. Is a family history of psychosis associated with reduced treatment delay? Schizophr Res. 2006;86:S117. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Judge AM, Estroff SE, Perkins DO, Penn DL. Recognizing and responding to early psychosis: a qualitative analysis of individual narratives. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:96–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boydell KM, Pong R, Volpe T, Tilleczek K, Wilson E, Lemieux S. Family perspectives on pathways to mental health care for children and youth in rural communities. J Rural Health. 2006;22:182–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stengler-Wenzke K, Trosbach J, Dietrich S, Angermeyer MC. Experience of stigmatization by relatives of patients with obsessive compulsive disorder. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2004;18:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L. On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance abuse. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:177–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT. The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? J Health Soc Behav. 1991;32:302–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. Am Psychol. 1999;54:765–76. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skeate A, Jackson C, Birchwood M, Jones C. Duration of untreated psychosis and pathways to care in first-episode psychosis: investigation of help-seeking behavior in primary care. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2002;43:73–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Haan L, Welborn K, Krikke M, Linszen DH. Opinions of mothers on the first psychotic episode and the start of treatment of their child. Eur Psychiatry. 2004;19:226–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lincoln C, Harrigan S, McGorry PD. Understanding the topography of the early psychosis pathways. An opportunity to reduce delays in treatment. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verdoux H, Liraud F, Bergey C, Assens F, Abalan F, van Os J. Is the association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome confounded? A two year follow-up study of first-admitted patients. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:231–41. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC. First-episode schizophrenia: I. Early course parameters. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:241–56. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:284–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. [30 May 2009];Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Available from URL: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/mentalhealth/cre/ [PubMed]

- 52.Nickerson KJ, Helms JE, Terrell F. Cultural mistrust, opinions about mental illness, and Black students' attitudes toward seeking psychological help from White counselors. J Couns Psychol. 1994;41:378–85. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Commander MJ, Cochrane R, Sashidharan P, Akilu F, Wildsmith E. Mental health care for Asian, black and white patients with non-affective psychosis: pathways to the psychiatric hospital, in-patient and after-care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:484–91. doi: 10.1007/s001270050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cooper-Patrick L, Powe N, Jenckes M, Gonzales J, Levine D, Ford D. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:431–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The stigma of psychiatric disorders and the gender, ethnicity, and education of the perceiver. Community Ment Health J. 2007;43:439–58. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alvidrez J, Havassy BE. Racial distribution of dual-diagnosis clients in public sector mental health and drug treatment settings. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:53–62. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keating F, Robertson D. Fear, black people and mental illness: a vicious circle? Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12:439–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alvidrez J, Snowden LR, Kaiser DM. The experience of stigma among Black mental health consumers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:874–93. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pincus FL. Discrimination comes in many forms: individual, institutional, and structural. Am Behav Sci. 1996;40:186–94. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hill RB. Structural Discrimination: The Unintended Consequences of Institutional Processes. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:194–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong C, Davidson L, McGlashan T, Gerson R, Malaspina D, Corcoran C. Comparable family burden in families of clinical high-risk and recent-onset psychosis patients. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2008;2:256–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2008.00086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]