Abstract

Purpose

Mammographic density and lobular involution are both significant risk factors for breast cancer, but whether these reflect the same biology is unknown. We examined the involution and density association in a large benign breast disease (BBD) cohort.

Patients and Methods

Women in the Mayo Clinic BBD cohort who had a mammogram within 6 months of BBD diagnosis were eligible. The proportion of normal lobules that were involuted was categorized by an expert pathologist as no (0%), partial (1% to 74%), or complete involution (≥ 75%). Mammographic density was estimated as the four-category parenchymal pattern. Statistical analyses adjusted for potential confounders and evaluated modification by parity and age. We corroborated findings in a sample of women with BBD from the Mayo Mammography Health Study (MMHS) with quantitative percent density (PD) and absolute dense and nondense area estimates.

Results

Women in the Mayo BBD cohort (n = 2,667) with no (odds ratio, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.3) or partial (odds ratio, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.6) involution had greater odds of high density (DY pattern) than those with complete involution (P trend < .01). There was no evidence for effect modification by age or parity. Among 317 women with BBD in the MMHS study, there was an inverse association between involution and PD (mean PD, 22.4%, 21.6%, 17.2%, for no, partial, and complete, respectively; P trend = .04) and a strong positive association of involution with nondense area (P trend < .01). No association was seen between involution and dense area (P trend = .56).

Conclusion

We present evidence of an inverse association between involution and mammographic density.

INTRODUCTION

Breast tissue undergoes a variety of changes with age. Age-related lobular involution, or physiologic atrophy of the breast, is a process wherein there is a reduction in the number and size of the acini per lobule and replacement of the intralobular stroma with dense collagen and, ultimately, fatty tissue.1,2 Milanese et al3 reported an inverse association between age-related lobular involution and breast cancer risk in a population of women with benign breast disease (BBD). Relative risks were 1.88 for no involution, 1.47 for partial involution, and 0.9 for complete involution compared with population-based incidence rates. Lobular involution was positively associated with age, such that complete involution was seen in only 3.4% of women younger than 30 years, increasing to 53% of women older than 70 years.3

Mammographic density is one of the strongest known risk factors for breast cancer.4 The biology underlying mammographic density is not well understood, but it has been hypothesized that the association between increased density and breast cancer risk may be due to the involution status of the breast tissue.5–7 The inverse association of density with age, as well as the positive associations with epithelial nuclear area and epithelial proliferation support this hypothesis,8,9 but to our knowledge as of yet, no studies have examined the association between density and lobular involution. In this report, we examine the association of age-related lobular involution with a measure of mammographic density in a cohort of women at Mayo Clinic with both mammograms and benign breast tissue.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study is based in the Mayo BBD cohort, a subset of whom had mammograms available for mammographic density estimation. A smaller corroborative study was performed using a more recent screening mammography cohort, the Mayo Mammography Health Study (MMHS), a subset of whom also had BBD diagnosed at Mayo Clinic and had tissue available. Both studies were approved by the Mayo Clinic institutional review board.

Study Population

The Mayo BBD cohort is comprised of 9,376 women, 18 to 85 years of age, with no prior history of breast cancer, diagnosed with BBD at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, between January 1, 1967, and December 31, 1991.10 BBD was diagnosed as a breast biopsy of a palpable or radiographic abnormality revealing benign findings. Women diagnosed with BBD between 1985 and 1991 (as parenchymal pattern was clinically recorded starting in 1985) and a mammogram within 6 months of BBD diagnosis were eligible for this study. Covariate information including age, parity, family history of breast cancer, body mass index (BMI), and postmenopausal hormone therapy use were obtained from the Mayo medical record and questionnaires mailed out to study participants or next of kin.

Pathology Assessment

The breast pathologists (D.V., C.R.), blinded to both BBD and density status, performed pathology review of all benign biopsy samples. BBD was categorized as nonproliferative disease, proliferative disease without atypia, or atypical hyperplasia.10 The extent of lobular involution was assessed in the normal background breast tissue on a hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide. Involuted terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs) only have a few to several small acini, flattened acinar epithelium, and fibrosis of specialized intralobular stroma.3 The degree of involution was classified into three categories: no involution (0% involuted TDLUs), partial (1% to 74% involuted TDLUs), or complete (≥ 75% involuted TDLUs).3

Mammographic Density Measure

Wolfe's parenchymal pattern was previously assessed and recorded on all mammograms at Mayo Clinic from 1985 through 1996. This assessment used all four views of the mammogram (right and left breast cranio-caudal, and medio-lateral oblique views) to clinically classify mammographic density on the basis of extent and type of density: N1, nondense, no ducts visible; P1, ductal prominence occupying less than a fourth of the breast; P2, prominent ductal pattern occupying more than a fourth of the breast; DY, homogenous, plaque-like areas of density.11 Multiple studies have shown parenchymal pattern is associated with breast cancer risk12–22 and has high interreader agreement.23,24

Statistical Analysis

Data are summarized in Table 1. We compared distributions of age and parity across levels of parenchymal pattern and involution using Mantel-Haenszel tests for trend. We examined associations between involution and parenchymal pattern using unconditional logistic regression analysis with parenchymal pattern as the outcome and involution as the predictor variable. Two sets of analyses were performed: one modeling the probability of nondense or N1 parenchymal pattern relative to the P1, P2, and DY patterns combined, and one modeling the probability of a dense pattern or DY relative to N1, P1, and P2 patterns combined. Odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated using complete involution as the referent group. We also assessed the dose-response effects of involution with parenchymal pattern using tests for trend, by coding the involution values as 0 for complete, 1 for partial, and 2 for no involution in a single variable that was included as a linear term in the logistic model. For each outcome, we initially examined associations in a univariate fashion. Subsequent models evaluated the potential confounding effects of age, parity, type of BBD, postmenopausal hormone use, family history of breast cancer (Table 1), and BMI (continuous variable) by including these terms as covariates in the logistic models. Final models were adjusted for age, parity, BMI, and postmenopausal hormone use. We also assessed whether age or parity might modify the association between involution and parenchymal pattern. To do this, we tested whether the odds ratios describing the association between involution status and parenchymal pattern differed by age or parity categories. All statistical tests were two sided, and all analyses were carried out using the SAS (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) software system.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the BBD and MMHS Cohorts

| Variable | BBD Cohort |

MMHS Cohort |

P† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Overall | 2,667 | 317 | |||

| Age at biopsy | |||||

| < 45 | 697 | 26.1 | 66 | 20.8 | .02 |

| 45-54 | 667 | 25 | 101 | 31.9 | |

| ≥ 55 | 1,303 | 48.9 | 150 | 47.3 | |

| BMI | |||||

| Mean | 26.4 | 26.8 | .27 | ||

| SD | 5.6 | 6.4 | |||

| Parity (No. of live births) | |||||

| Unknown | 221 | 11 | .16 | ||

| Nulliparous | 359 | 14.7 | 46 | 15.0 | |

| 1 | 276 | 11.3 | 30 | 9.8 | |

| 2 | 680 | 27.8 | 103 | 33.7 | |

| 3 or more | 1,131 | 46.2 | 127 | 41.5 | |

| Family history breast cancer* | |||||

| Unknown | 266 | 14 | < .001 | ||

| Negative | 1,542 | 64.2 | 244 | 80.5 | |

| Positive | 859 | 35.8 | 59 | 19.5 | |

| Involution status (3-category) | |||||

| None, 0% | 359 | 13.5 | 21 | 6.6 | < .001 |

| Partial, 1%-74% | 1,666 | 62.5 | 224 | 70.7 | |

| Complete, ≥ 75% | 642 | 24.1 | 72 | 22.7 | |

| BBD histology | |||||

| NPD | 1,556 | 58.4 | 186 | 58.7 | .05 |

| PDWA | 954 | 35.8 | 102 | 32.2 | |

| AH | 156 | 5.9 | 29 | 9.2 | |

| Quartiles of percent density | |||||

| Q1, ≤ 10.6% | NA | 80 | 25.2 | ||

| Q2, 10.7%-23.4% | NA | 79 | 24.9 | ||

| Q3, 23.5%-36.0% | NA | 80 | 25.2 | ||

| Q4, > 36.0% | NA | 78 | 24.6 | ||

| Parenchymal pattern | |||||

| N1 | 555 | 20.81 | NA | ||

| P1 | 378 | 14.17 | NA | ||

| P2 | 642 | 24.07 | NA | ||

| DY | 1,092 | 40.94 | NA | ||

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy | |||||

| Unknown | 514 | 24 | .001 | ||

| Never | 948 | 44 | 159 | 54.3 | |

| Ever | 1,205 | 56 | 134 | 45.7 | |

Abbreviations: BBD, benign breast disease; MHHS, Mayo Mammography Health Study; BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; NA, not available; NPD, nonproliferative disease; PDWA, proliferative disease without atypia; AH, atypical hyperplasia; Q, quartile; N1, nondense; P1, prominent ductal pattern occupying less than a fourth of the breast; P2, prominent ductal pattern occupying more than a fourth of the breast; DY, homogenously dense.

Positive family history was defined as a first-, second-, or third-degree relative with breast cancer (BBD study) or a first-degree relative with breast cancer (MMHS study).

P value testing for differences in distribution across the two cohorts (heterogeneity) using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Corroborative Study in the MMHS Cohort

To replicate our findings with a quantitative measure of density in a recently established cohort, we examined the involution and mammographic density association among 317 women with BBD diagnoses within the MMHS cohort. The MMHS cohort consists of 19,948 women older than 35 years without a history of breast cancer, living in MN, WI, or IA, who had a screening mammogram between October 1, 2003, and September 30, 2006, at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Women in the cohort who had either a core-needle or surgical breast biopsy resulting in benign findings at the Mayo Clinic were identified using a clinical database. Participants who had a biopsy within 2 years of their enrollment mammogram were eligible for this study. Weight and height (to calculate BMI) at enrollment mammogram were available from clinical databases. Detailed information on other covariates were available through a questionnaire completed by all participants at enrollment.

Mammographic density was measured from the craniocausal view6 using a validated thresholding algorithm (Cumulus)25 that provides estimates of percentage density (PD; 0% to 100%) and absolute amounts of dense and nondense tissue (in cm2). The PD estimate has been well characterized26 and consistently yields a strong association with breast cancer.4,9,27–29

We compared demographic and clinical characteristics in the MMHS with those in the BBD cohort using a test for heterogeneity. The association between involution and density was examined using generalized linear models. Separate models were fit with PD, dense area, and nondense area as the outcome variables and the same three-category measure of involution as the predictor. The distributions of density measures were skewed and transformed by using a square root transformation. The involution-specific least square mean estimates and 95% CIs from these models were then back-transformed for presentation. The dose-response effects of involution with density were assessed using tests for trend. Confounders and modifiers were evaluated as in the BBD study.

RESULTS

Of the 3,271 women from the Mayo BBD cohort diagnosed with BBD between 1985 and 1991, 2,667 (82%) had a mammogram within 6 months of BBD diagnosis (mean interval, 11.1 [SD, 19.8] days). This sample of women from the BBD study cohort were similar but slightly older and had a greater proportion nulliparous women compared with the overall Mayo BBD cohort of 9,376 women (mean age, 55 years; standard deviation [SD], 14; 15% nulliparous, 64% with no family history of breast cancer for the study cohort, compared with mean age of 51; SD, 14; 10% nulliparous, 66% with no family history of breast cancer for the overall BBD cohort).10 The greater proportion of atypical hyperplasia in the study cohort compared with the overall BBD cohort (6% v 3%) was likely a result of the advent of screening mammography in the 1980s and increased identification of abnormal calcifications and thereby, of atypia. Table 1 also demonstrates that a large proportion of women in the study sample had high breast density (65% had a P2 or DY category).

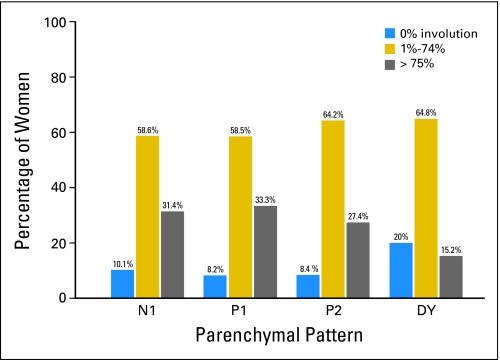

The overall distribution of involution by parenchymal pattern suggests a greater proportion of women with N1 density or fatty mammograms have complete involution while greater proportion of women with DY density have no involution (data not shown). However, there was considerable overlap of the extent of involution across all four parenchymal pattern categories (Fig 1). In fact, the proportion of women with complete involution was only reduced among women in the DY category; 31%, 33%, 27%, and 15% of women had complete involution in the N1, P1, P2, and DY categories.

Fig 1.

Distribution of involution and parenchymal pattern in the Mayo Clinic benign breast disease cohort. N1, nondense; P1, prominent ductal pattern occupying less than a fourth of the breast; P2, prominent ductal pattern occupying more than a fourth of the breast; DY, homogenously dense.

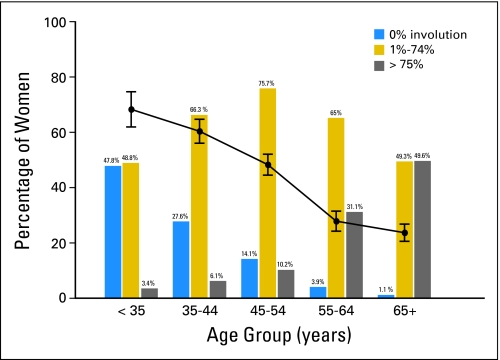

Associations between age and both parenchymal pattern and involution are graphically displayed in Figure 2. Increasing age was associated with a shift from a higher to lower proportion of DY patterns and a shift from no involution toward complete involution (tests for trend P < .001 for each). Parous women were more likely to have fatty mammograms or N1 pattern (P < .001), but there was no significant evidence for an association between parity and involution (P = .44; data not shown).

Fig 2.

Involution and parenchymal pattern by age at diagnosis of benign breast disease in the benign breast disease cohort. Solid line indicates proportion of women in each age group with homogenously dense pattern (DY).

After adjustment for age, parity, BMI, and postmenopausal hormone use, women with no involution (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2 to 2.3) and partial involution (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.6) were more likely to have a high density DY pattern than those with complete involution (P for trend < .01; Table 2). In contrast, women with no involution (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5 to 1.0) and partial involution (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6 to 1.0) appeared less likely to have a low-density N1 pattern compared with women with complete involution (P for trend .02; Table 2). Further adjustment for family history of breast cancer and type of BBD did not appreciably change results (data not shown). Also, there was no significant evidence that the involution and density association differed by categories of age or parity (P > .05 for each).

Table 2.

Association of Involution With Parenchymal Pattern in the Mayo Clinic Benign Breast Disease Cohort

| Involution Category | Total No. | N1 v P1, P2, DY Combined |

DY v N1, P1, P2 Combined |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted* |

DY |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted* |

||||||||

| No. | % | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | No. | % | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| None, 0% | 359 | 56 | 10.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 to 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.5 to 1.0 | 218 | 20 | 4.4 | 3.4 to 5.8 | 1.7 | 1.2 to 2.3 |

| Partial, 1%-74% | 1,666 | 325 | 58.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 to 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.6 to 1.0 | 708 | 64.8 | 2.1 | 1.7 to 2.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 to 1.6 |

| Complete, ≥ 75% | 642 | 174 | 31.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 166 | 15.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| P for trend | < .01 | .02 | < .01 | < .01 | |||||||||

Abbreviations: N1, nondense; P1, prominent ductal pattern occupying less than a fourth of the breast; P2, prominent ductal pattern occupying more than a fourth of the breast; DY, homogenously dense.

Adjusted for age, parity, body mass index, and postmenopausal hormone therapy.

Corroborative Study in MMHS Study Cohort

The 317 women in the MMHS were similar to the BBD study cohort with regard to BMI and parity, but differed in their distributions of age, family history, involution status, BBD histology, and postmenopausal hormone use (Table 1). Similar to the BBD study cohort, after adjustment for age, parity, BMI, and postmenopausal hormones, there was an inverse association between involution and PD (adjusted mean PD, 22.4% [95% CI, 16.2 to 29.7], 21.6% [95% CI, 19.3 to 24.0], and 17.2% [95% CI, 13.9 to 20.9] for no, partial, and complete involution, respectively; P for trend .04; Table 3). When examining absolute dense area and involution, however, there was no evidence for an association, with adjustment for covariates. There was a positive association between involution and nondense area (mean nondense area cm2, 106.8 [95% CI, 88.6 to 126.7], 105.4 [95% CI, 98.7 to 112.4], 128.6 [95% CI, 116.4 to 141.4] for categories of no, partial, or complete involution, respectively; P for trend < .01). Tests for interaction did not reveal any evidence for effect modification by age or parity (P > .05 for each).

Table 3.

Association of Involution and Percent Density, Dense Area, and Nondense Area in Patients With Benign Breast Disease Within the Mayo Mammography Health Study Cohort

| Involution Category | No. | Mean Area (cm2) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Percent Density |

Dense |

Nondense |

|||||||||||

| Unadjusted | 95% CI | Adjusted* | 95% CI | Unadjusted | 95% CI | Adjusted* | 95% CI | Unadjusted | 95% CI | Adjusted* | 95% CI | ||

| No | 21 | 28.4 | 20.3 to 38.0 | 22.4 | 16.2 to 29.7 | 31.3 | 21.8 to 42.4 | 27.2 | 18.2 to 37.9 | 88.6 | 67.1 to 115.1 | 106.8 | 88.6 to 126.7 |

| 1-74% | 224 | 23.5 | 21.1 to 26.0 | 21.6 | 19.3 to 24.0 | 28.8 | 25.8 to 31.9 | 27.2 | 23.7 to 30.9 | 100.5 | 92. to 108.8 | 105.4 | 98.7 to 112.4 |

| ≥75% | 72 | 12.2 | 9.3 to 15.6 | 17.2 | 13.9 to 20.9 | 20.7 | 16.4 to 25.4 | 25.1 | 19.7 to 31.1 | 150.2 | 133. to 168.1 | 128.6 | 116.4 to 141.4 |

| P for trend | < .01 | .04 | < .01 | .56 | < .01 | < .01 | |||||||

Adjusted for age at biopsy, parity, body mass index, and postmenopausal hormone therapy.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, we present the first evidence of an inverse association between mammographic density and age-related lobular involution in a large sample of women from a well-characterized BBD cohort. Findings were similar in a corroborative study using a quantitative PD measure. In addition, there was a positive association of nondense area, reflecting fat tissue, with complete involution. However, the absolute area of dense tissue was not significantly associated with involution after adjustment for covariates. Mammographic density may, in part, reflect histologic changes associated with lobular involution.

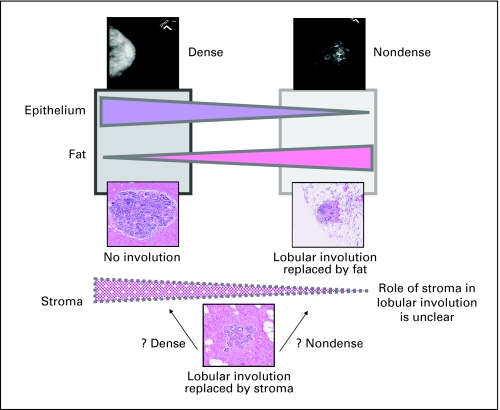

Age-related lobular involution reflects a process of physiologic atrophy of the breast glandular epithelium. It is believed that the epithelium is first replaced by stroma,2,3 and, with time, the stroma is replaced by fat, such that completely involuted breast tissue is composed of atrophic epithelium and fat. This is in contrast to the preclimacteric involution associated with selective atrophy of the breast glandular epithelium with decrease in the amount of lobular and acinar tissue.1 Histologic studies of mammographic density have shown that dense tissue reflects both breast epithelial tissue as well as stroma in the form of stromal fibrosis, proliferation, and deposition of collagen.9,30 However, nondense tissue primarily reflects fatty tissue in the breast.

Thus, the overall measure of mammographic density, whether by parenchymal pattern or PD, reflects the proportion (or in the case of dense area, the amount) of the breast composed of both stroma and epithelial tissue but is unable to distinguish between tissue type. Lobular involution primarily reflects the atrophy of the glandular epithelium. If lobular involution is associated with replacement of lobules exclusively by stroma, we would expect a positive association between dense area and PD with involution, contrary to our findings of an inverse association between PD, parenchymal pattern, and involution. However, the lack of a statistically significant association between absolute dense area and involution status suggests that the involuted lobules may be replaced by stroma and/or fat. As involution progresses, further replacement of lobular epithelium and stroma with fat explains the strong inverse association between complete involution and nondense (or fatty) breast tissue. We summarize the above potential interrelationships between histologic correlates of involution and density in Figure 3. Defining how lobular involution occurs in individual women, the role of the stroma in this process, and the relationship of these events with mammographic density, is not yet understood but is critical to understanding the biology underlying the involution and density association.

Fig 3.

Hypothesized association between mammographic density, lobular involution, and breast tissue composition. Mammographically dense tissue represents higher proportions of epithelium and stroma, and less fat. Our results indicate a positive association of percent mammographic density with lack of lobular involution. However, the association between stroma and lobular involution in regards to mammographic density is yet unclear. Potentially, women with lobular involution but higher percent density have a strong stromal, rather than fat component.

We, and others, have hypothesized that mammographic density directly reflects the involution process.5,7,29 However, our findings demonstrate that this relationship is complex. Table 2 shows an inverse association between lobular involution and density. While only 31% of women with fatty breasts (N1 pattern) showed complete involution, 15% of women with densest breasts (DY pattern) also showed complete involution (Fig 1). Results from the MMHS cohort show an inverse trend between involution and percent density with no association between absolute dense area and involution, but positive association between nondense area and involution (Table 3). These findings suggest that mammographic density is not solely mirroring the process of lobular involution, but also depends on the replacement of the atrophic lobules with stroma and/or fat. The inconsistency seen with the dense area and involution association could also reflect the small sample size of those with BBD in the MMHS cohort. Moreover, our assessments of both lobular involution and density are crude measures. With more precise estimation of both, a stronger magnitude of association may emerge. Nevertheless, the above findings are intriguing and support the need for further studies to clarify the complex association between involution and mammographic density, and their influence on breast cancer risk.

Lobular involution and mammographic density have both been shown to reflect a global process occurring throughout the breast rather than a localized feature.6,31 Lobular involution, assessed in tissue from four quadrants of both breasts of 15 women who had undergone prophylactic mastectomy, showed strong intrawomen concordance of involution status across all the eight quadrants (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.89). Thus, involution assessed from a single biopsy site may actually reflect the status of the entire breast. This finding also parallels the recent data by our group that showed mammographic density to be a global marker of risk.6 Thus, both elevated density and reduced lobular involution could be reflective of, or contribute to, an underlying global mechanism associated with elevated breast cancer risk. However, mammographic density decreases with age and involution increases with age, yet breast cancer risk increases with age. Boyd et al have hypothesized that this paradox is consistent with Pike's construct of “breast tissue ageing”32; such that the cumulative exposure of breast tissue to factors that stimulate cell division and accumulation of genetic damage in breast cells, potentially reflected in increased mammographic density and delayed involution, may be more relevant to breast cancer risk than chronologic age.7 However, more research is necessary to understand the mechanisms by which involution and density influence risk, including investigations incorporating the emerging data on breast cancer subtypes.

The strength of this report lies in the use of a large, well-characterized cohort of women with BBD and corroboration using a recent cohort with quantitative measures of density and identical assessment of involution by the same pathologists. While the parenchymal pattern was assessed by multiple radiologists for predominantly clinical purposes, it has been used in several studies12–22 with high interreader reliability.23,24 We also acknowledge that the study has certain limitations. We did not have BMI data on all women in the Mayo BBD cohort as a result of missing height information, but analyses with inclusion of weight measure did not change our results. The study population of both cohorts is predominantly white representing the upper Midwest population of the United States, emphasizing the need for further studies in diverse populations. We also recognize that the two study populations were different in terms of timing of BBD diagnoses and composition of the sample. The Mayo BBD cohort was an older cohort with predominantly excisional benign breast biopsies for palpable lesions, unlike the MMHS screening cohort, with primarily core biopsies. However, the similar findings in two BBD populations that span three decades are encouraging. Also, the study findings can only be generalized to women having a benign breast biopsy but this population is at increased breast cancer risk compared with the general population.

In conclusion, we provide evidence for an inverse association between mammographic density and lobular involution. The data presented in this report are provocative and support the need for continued research to understand the mechanisms underlying age-related lobular involution and density, as well as their influence, independent or otherwise, on breast cancer risk.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. SPORE P50 CA116201, R01 CA46332, R01 CA97396, K12 RR24151 from the National Institutes of Health; by Grant No. FEDDAMD17-02-1-0473-1 from the Department of Defense; by Grant No. BCTR 99-3152 from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation; by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation; and by the Andersen Foundation.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Karthik Ghosh, Lynn C. Hartmann, Thomas A. Sellers, Celine M. Vachon

Financial support: Celine M. Vachon

Administrative support: Celine M. Vachon

Provision of study materials or patients: Lynn C. Hartmann, Carol Reynolds, Daniel W. Visscher, Kathleen R. Brandt, Celine M. Vachon

Collection and assembly of data: Lynn C. Hartmann, Carol Reynolds, Daniel W. Visscher, Kathleen R. Brandt, Robert A. Vierkant, Christopher G. Scott, Celine M. Vachon

Data analysis and interpretation: Karthik Ghosh, Lynn C. Hartmann, Robert A. Vierkant, Christopher G. Scott, Derek C. Radisky, V. Shane Pankratz, Celine M. Vachon

Manuscript writing: Karthik Ghosh, Lynn C. Hartmann, Robert A. Vierkant, Christopher G. Scott, Derek C. Radisky, Thomas A. Sellers, V. Shane Pankratz, Celine M. Vachon

Final approval of manuscript: Karthik Ghosh, Lynn C. Hartmann, Carol Reynolds, Daniel W. Visscher, Kathleen R. Brandt, Robert A. Vierkant, Christopher G. Scott, Derek C. Radisky, Thomas A. Sellers, V. Shane Pankratz, Celine M. Vachon

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes LE, Mansel RE. Breast anatomy and physiology. In: Hughes LE, Mansel RE, Webster DJT, editors. Benign Disorders and Diseases of the Breast: Concepts and Clinical Management. London, United Kingdom: W.B. Saunders; 2000. pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vorrherr H. New York, Ny: Academic Press; 1974. The Breast: Morphology, Physiology, and Lactation. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milanese TR, Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, et al. Age-related lobular involution and reduced risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1600–1607. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:227–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henson DE, Tarone RE. Involution and the etiology of breast cancer. Cancer. 1994;74:424–429. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820741330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vachon CM, Brandt KR, Ghosh K, et al. Mammographic breast density as a general marker of breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:43–49. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginsburg OM, Martin LJ, Boyd NF. Mammographic density, lobular involution, and risk of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1369–1374. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Sun L, Miller N, et al. The association of measured breast tissue characteristics with mammographic density and other risk factors for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:343–349. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd NF, Lockwood GA, Byng JW, et al. Mammographic densities and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:1133–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfe JN. Breast patterns as an index for developing breast cancer. Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:1130–1137. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.6.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moskowitz M, Pemmaraju S, Russell P, et al. Observations on the natural history of carcinoma of the breast, its precursors, and mammographic counterparts: Part 2: Mammographic patterns. Breast Dis Breast. 1977;3:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkinson E, Clopton C, Gordonson J, et al. Mammographic parenchymal pattern and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;59:1397–1400. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.5.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyd NF, O'Sullivan B, Campbell JE, et al. Mammographic signs as risk factors for breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1982;45:185–193. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1982.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brisson J, Merletti F, Sadowsky NL, et al. Mammographic features of the breast and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:428–437. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brisson J, Morrison AS, Kopans DB, et al. Height and weight, mammographic features of breast tissue, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:371–381. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlile T, Kopecky KJ, Thompson DJ, et al. Breast cancer prediction and the Wolfe classification of mammograms. JAMA. 1985;254:1050–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe JN, Saftlas AF, Salane M. Mammographic parenchymal patterns and quantitative evaluation of mammographic densities: A case-control study. Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:1087–1092. doi: 10.2214/ajr.148.6.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brisson J, Verreault R, Morrison AS, et al. Diet, mammographic features of breast tissue, and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:14–24. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saftlas AF, Wolfe JN, Hoover RN, et al. Mammographic parenchymal patterns as indicators of breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:518–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brisson J. Family history of breast cancer, mammographic features of breast tissue, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiology. 1991;2:440–444. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199111000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, et al. Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: Effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1622–1629. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.21.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J, Warren R, Warren-Forward H, et al. Reproducibility of visual assessment on mammographic density. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:121–127. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9581-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyd NF, Wolfson C, Moskowitz M, et al. Observer variation in the classification of mammographic parenchymal patterns. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:465–472. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byng JW, Boyd NF, Fishell E, et al. The quantitative analysis of mammographic densities. Phys Med Biol. 1994;39:1629–1638. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/39/10/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, et al. Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: Results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:670–675. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.9.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee-Han H, Cooke G, Boyd NF. Quantitative evaluation of mammographic densities: A comparison of methods of assessment. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1995;4:285–292. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199508000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vachon CM, van Gils CH, Sellers TA, et al. Mammographic density, breast cancer risk and risk prediction. Breast Cancer Res. doi: 10.1186/bcr1829. doi: 10.1186/bcr1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo YP, Martin LJ, Hanna W, et al. Growth factors and stromal matrix proteins associated with mammographic densities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vierkant RA, Hartmann LC, Pankratz VS, et al. Lobular involution: Localized phenomenon or field effect? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:193–196. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0082-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pike MC, Krailo MD, Henderson BE, et al. ‘Hormonal’ risk factors, ‘breast tissue age’ and the age-incidence of breast cancer. Nature. 1983;303:767–770. doi: 10.1038/303767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.