Abstract

Typing of STR (short tandem repeat) alleles is used in a variety of applications in clinical molecular pathology, including evaluations for maternal cell contamination. Using a commercially available STR typing assay for maternal cell contamination performed in conjunction with prenatal diagnostic testing, we were posed with apparent nonmaternity when the two fetal samples did not demonstrate the expected maternal allele at one locus. By designing primers external to the region amplified by the primers from the commercial assay and by performing direct sequencing of the resulting amplicon, we were able to determine that a guanine to adenine sequence variation led to primer mismatch and allele dropout. This explained the apparent null allele shared between the maternal and fetal samples. Therefore, although rare, allele dropout must be considered whenever unexplained homozygosity at an STR locus is observed.

Tandemly repeated DNA sequences are widespread throughout the human genome.1 They show sufficient variability between individuals in a population to be used in several fields of molecular biology including genetic mapping, linkage analysis, and human identity testing.2,3,4 Most used in these applications are the microsatellite regions (short tandem repeats [STRs]), which contain between three and five repeats.3 Although there are hundreds of STR regions that have been mapped throughout the human genome, only several dozen have been studied sufficiently for application to human identity testing. Several commercial assays that identify these STRs are in widespread use.5 The most used assays rely on PCR amplification of various STRs followed by fragment electophoretic analysis. They provide premixed primers, polymerase, buffers, and deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate, and include highly polymorphic markers that render these assays informative in the majority of cases.

One application for STR testing is the detection of maternal cell contamination (MCC) in a fetal specimen. Maternal cell contamination can lead to misdiagnosis of a prenatal specimen.6 Even small quantities of maternal cell contamination containing genetic material can pose an analytical risk when the assay involves selective nucleic acid amplification, for example, as in a PCR. Therefore, it is important to determine whether maternal cell contamination is present in the fetal specimen being analyzed. To do so, an STR typing assay is performed for both the maternal and fetal specimens and a comparison is made between the two samples. Because of Mendelian genetics, it is expected that the fetal specimen will share one STR allele at each locus with the mother and one with the father. The presence of a second allele from the mother in the fetal specimen would, therefore, indicate the presence of maternal cell contamination in the extracted genetic material. Of note, a single stutter peak is often seen preceding an STR on the electropherogram and must be taken into consideration when interpreting a maternal cell contamination assay.5 A marker, therefore, is informative only if the mother's sample contains a second allele that is not shared with the fetus and it does not occur at the location of the fetal stutter peaks. Most labs require two or three informative STR makers in order for a definitive negative result to be issued.6

Sometimes, STR typing analysis can result in unexpected findings. In theory, the presence of inhibitors that co-purify with the DNA may lead to amplification difficulties of some or all alleles. In addition, allele dropout or the presence of rare alleles may lead to an allele that remains undetected in the analysis.7 The issue addressed in this consultation is the topic of allele dropout, manifesting as a null allele. In allele dropout, if a sequence variation occurs in the PCR binding site used to amplify the STR allele, it may decrease or negate the efficiency of PCR amplification.5 This is especially true if the sequence variation occurs immediately proximal to the 3′ end of the primer.8,9 The sample being analyzed will, therefore, falsely appear to be homozygous at that locus. For example, in one concordance study, of 1500 samples drawn from different ethnicity pools (excluding Chamorro and Filipino individuals), 0.2% to 0.3% of the samples demonstrated typing differences secondary to allele dropout when assayed with two different commercial STR typing tests.7 Other studies revealed an average allele dropout rate per typing assay of approximately 0.2% to 0.5%.10,11 Detection of the allele that appears to be a null allele can be accomplished if a different set of PCR primers is used for amplification of the STR segment. In this report we address the issue of apparent nonmaternity at the D8S1179 locus in an MCC assay and describe how we were able to identify the causative sequence variation resulting in the discrepancy between the fetal and maternal samples.

Materials and Methods

Case Reports

The patient was a woman who presented to the genetics clinic for counseling regarding α thalassemia in her family. She was carrying two fetuses. Oocyte retrieval had been performed repeatedly at our institution because of a diagnosis of infertility, but the in vitro fertilization procedure had been performed at another institution. It was reported to the lab that both parents carried specific α thalassemia deletions, and we concluded that the couple was at risk for transmitting hemoglobin H disease. Amniocentesis was performed to evaluate for α thalassemia deletions by using a PCR-based assay system. An MCC study was also ordered for use in conjunction with the interpretation of the α thalassemia test results. The results of the α thalassemia assay were to be used for prenatal counseling.

Samples

DNA was extracted from a whole blood sample collected in EDTA from the mother and amniotic fluid samples from the twin fetuses. For the mother's sample, DNA was extracted from 350 μl of whole blood by using the Qiagen EZ1 BioRobot in conjunction with the EZ1 DNA Blood reagents (Qiagen, Inc, Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For the twins' samples, cells were centrifuged to pellet the cells, washed with PBS buffer, again centrifuged and then the pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of PBS buffer. The DNA was then extracted by using modified manufacturer's recommendations for the Qiagen Mini Blood Kit (Qiagen, Inc). Modifications included adding 200 μl AL lysis solution to the tube containing the amniocyte pellet, pulse vortexing for 20 seconds, and incubating in a 56°C heat block for 15 minutes before adding 200 μl of EtOH. The isolated DNA was quantified by using a Nanodrop instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, Waltham, MA). Dilution with tris-EDTA buffer was performed to achieve a final concentration of 0.5 ng/μl of DNA for each sample.

STR Typing Using Applied Biosystems

The DNA preparations were amplified by using the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus PCR Amplification Kit (category number 430332; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, a PCR master mix was created that contained 21 μl of AMPF/STR PCR reaction, 1.0 μl of AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase, and 11 μl of AMPF/STR Profiler Plus Primer Set per DNA reaction to be performed. Thirty microliters of the PCR master mix was then added to 20 μl of patient DNA for a total volume of 50 μl. The mother's DNA was run one time, and the fetal samples were run in duplicate at a concentration of 0.5 ng/μl. In addition, a sensitivity control that is a mix of 99% of one sample and 1% of another sample was also run at a concentration of 0.5 ng/μl. For a negative control, 20 μl of PCR water instead of DNA was used. Amplification conditions were one cycle at 95°C for 11 minutes, 28 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 59°C for 1 minute, 72°C for 1 minute, and one cycle of 60°C for 45 minutes.

PCR Sample Analysis GeneScan on ABI 3100

To prepare each PCR reaction sample for analysis, 1 μl of PCR product was added to 0.5 μl of GeneScan-500 Rox size standard (Applied Biosystems) and 9 μl of Hi-Di formamide (Applied Biosystems) and placed into each well. Samples were denatured by placing them at 95°C for 3 minutes, snap-chilled on ice water for 5 minutes, and then loaded onto the ABI 3100 analyzer (Applied Biosystems) for electrophoretic analysis. GeneMapper software was used to aid in electrophoresis peak analysis.

Sequence Analysis

Salt-free sequencing primers MCCInvF and MCCInvR were synthesized by Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). These primers lie external to the publicly available primer sets used to amplify the D8S1179 allele12 (see Figure 1)13 and create an approximately 400 to 420 bp product, with the exact size being dependent on the number of STRs present. The primer sequences are as follows: MCCInvF 5′-TACAGGATCCTTGGGGTGTC-3′ and MCCInvR 5′-CATTGTTGTTGGGAATGT-3′. The DNA samples originally isolated from the mother and both fetal specimens were subjected to PCR amplification of the D8S1179 region. The PCR mix consisted of 250 μmol/L dNTP, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1x Qiagen PCR buffer, 1x Qiagen Q-solution, 2.5 U Qiagen HotSTAR Plus Taq, 0.5 μmol/L MCCInvF primer, 0.5 μmol/L MCCInvR primer, and 50 ng DNA in a final reaction volume of 25 μl. PCR amplification conditions were one cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes, 37 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 53°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 1 minute, and one cycle of 72°C for 10 minutes. Five microliters of each reaction was run on a 1.7% agarose gel (Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA) in tris-acetate-EDTA buffer with ethidium bromide for 1 hour to visualize the PCR product. To isolate different PCR products in each reaction tube, 5 μL of each reaction was run on a 4% Nusieve (BMA, Rockland, ME) agarose gel in TAE buffer with ethidium bromide for 4 hours. Individual bands were visualized by using UV light, excised with a razor blade, and then the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Inc) was used to prepare the DNA for sequencing.

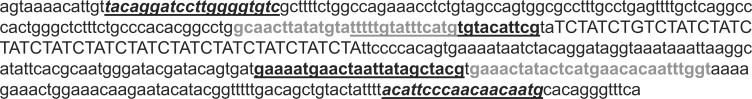

Figure 1.

Genomic nucleotide sequence (5′->3′) of the D8S1179 STR and flanking genomic sequence with primer sets used for its amplification. The sequence is from chromosome 8q24.13, GenBank sequence AF216671 (the original sequence clone, GenBank sequence G08710, is similar to the sequence listed, differing only in repeat pattern present). Location of the D8S1179 STR locus is indicated by capitalization. Location of publicly available primer sets is indicated by an underline13 and in gray (Promega PowerPlex 16 primer set; Promega Corp). The location of our sequencing primer set MCCInvF and MCCInvR is indicated in italics.

Sequencing of the PCR product was performed by using the BigDye version 3.1 Terminator DNA Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Sequence Analysis 5.2 software was used to help analyze the raw data.

Results

DNA extracted from the maternal and fetal samples was subjected to STR typing analysis by using the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus assay from Applied Biosystems. The assay types nine tetranucleotide repeat markers. For eight of the nine STR markers, at least one maternal STR allele was present in each of the fetal samples (data not shown). For five of eight of these marker loci (D3S1358 [vWA in Fetus A and FGA in Fetus B], D21S11, D5S818, and D13S317), the maternal sample's alleles were either identical to the fetal samples' alleles or the second maternal allele occurred at the location of the fetal allele's stutter peak, and therefore these markers were noninformative for maternal cell contamination in the fetal samples. For three of the eight markers ([FGA in Fetus A and vWA in Fetus B], D18S51, and D7S820), the second maternal allele occurred at a location that differed from those in the fetal samples and did not occur at the location of a fetal allele stutter peak. Therefore, these were loci informative for maternal cell contamination. These informative loci showed no evidence of maternal cell contamination. Figure 2 shows the electopherograms at the ninth locus, the D8S1179 STR, for the maternal sample, fetal sample A and fetal sample B. At this locus, there was no maternal allele present in the fetal samples. The mother appears to be homozygous for the 10 repeat STR allele (Figure 2A), whereas fetal sample A appears homozygous for the 13 repeat STR allele (Figure 2B), and fetal sample B appears homozygous for the 14 repeat STR allele (Figure 2C). The assay was repeated and showed identical results.

Figure 2.

AMPF/STR Profiler Plus D8S1179 STR electopherograms for mother and two fetal samples. A: The maternal sample appears homozygous for a 10 STR allele. B: Fetal sample A appears homozygous for a 13 repeat allele. C: Fetal sample B appears homozygous for a 14 repeat allele. The x axis indicates elution time units.

At this point we were faced with two dilemmas: how to explain the results at the D8S1179 locus and how to interpret the maternal cell contamination assay results. The lack of a maternal allele at locus D8S1179 in the two fetal samples could most likely be explained by either nonmaternity or the presence of a null allele. We hypothesized that, had the pregnant woman not been able to conceive by using the oocytes retrieved from her ovaries, she might have been implanted with an embryo created by using an egg from a donor. A donor would have had to be closely related, possibly a sister, because STR alleles were shared between the woman carrying the fetuses and the fetal samples at eight of nine loci. Alternatively, the pregnant woman and these fetuses shared a null allele that did not amplify. Less likely, but still theoretically possible, is that both fetuses have paternal disomy at the D8S1179 loci.14,15 In our lab, we require that three of the nine tetranucleotide repeat markers be informative for the possibility of maternal cell contamination in order for a negative result to be issued. In this case, three loci were informative, so we felt comfortable concluding that maternal cell contamination was not present at the level of detection validated in our lab. This was important because the samples were amniotic samples and the prenatal PCR based α thalassemia assay interpretation depended on the results from the MCC study. Whether the woman carrying the fetuses was the biological mother or not was less relevant because the MCC studies were negative.

For internal quality control reasons, we investigated the cause of the discrepant results at the D8S1179 STR locus. Because both the mother and the fetuses demonstrated homozygosity at this marker, we thought that there was a good chance that the results could be explained by allele dropout. Searching the literature, we identified two publicly available primer sets used to amplify the D8S1179 marker (12, Promega PowerPlex 16 primer set [Promega Corp, Madison, WI]; Figure 1).13 We were told by technical support at Applied Biosystems that the primer sequences for the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus assay kit are not released to the public. We, therefore, designed PCR primers that would amplify the D8S1179 STR, the publicly available primer binding sites, and an additional 50 to 80 bp flanking each side of this region. By using primers significantly external to the known primer binding sites, we hoped to detect any sequence changes in the likely primer binding site region and to determine whether there was a null allele present. The maternal sample clearly demonstrated two unique bands at approximately 400 and 415 bp, suggesting the presence of two alleles at D8S1179 (Figure 3A). Only one thick band at approximately 410 to 420 bp was visualized for each of the two fetal samples. The PCR products were then run on a 4% Nusieve-Agarose gel in an attempt to get better resolution between the bands. Similar resolution was seen as had been seen on the agarose gel (data not shown). For the maternal sample, two bands were cleanly excised from the gel. For the fetal samples, the lower and upper quarters of the single thicker band were excised from the gel in an attempt to isolate any different alleles that might be present. The gel bands were then prepared for sequencing.

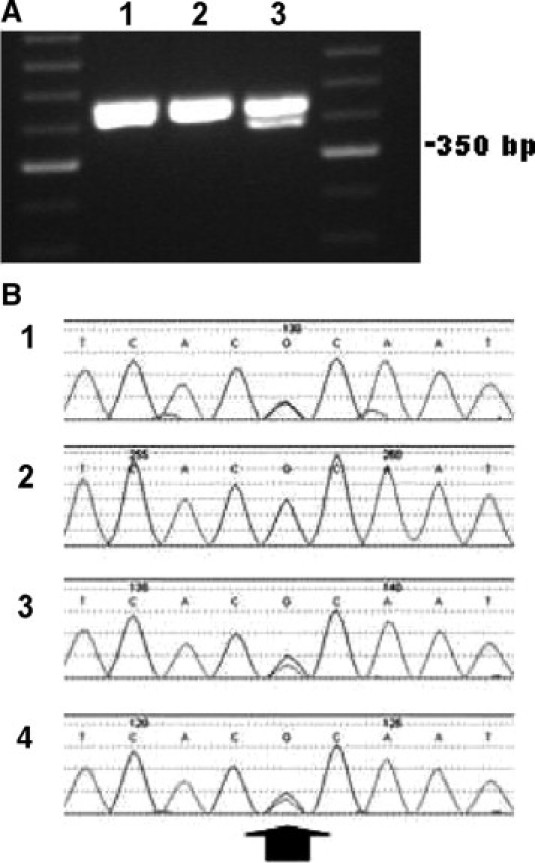

Figure 3.

A: PCR products generated by MCCInvF and MCCInvR primers run on a 1.7% agarose gel. (1) Fetal sample A. (2) Fetal sample B. (3) The maternal sample. The presence of two bands in the maternal sample lane indicates amplification of two D8S1179 alleles. Only single thick bands are seen in the fetal samples. The DNA ladder used for sizing is a 50-bp ladder. B: Sequencing data for maternal and fetal D8S1179 alleles. (1) The upper band from the maternal sample. (2) The lower band from the maternal sample. (3) Fetus A. (4) Fetus B. An arrow indicates the location of the G to A sequence change identified 56-bp downstream of the D8S1179 STR locus. This G>A change is present in sequence panels 1, 3, and 4.

Using the same primers designed to create the amplicon, the six isolated gel fragments were independently sequenced. The lower maternal band gave a single genetic signal of 10 TCTA repeats ([TCTA]10) at the D8S1179 STR. The upper band gave a mixed signal consisting of the 10 repeat STR seen in the lower band and a 15 repeat STR ([TCTA]2[TCTG]1[TCTA]12). Because only a 10 STR allele was seen in the electropherogram following amplification with the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus kit, the 15 STR allele was not amplified with the D8S1179 primer set included in that assay. For the fetal specimens, both the upper and lower quartiles of the PCR band yielded identical sequencing results. Fetal sample A was found to contain both a 13 STR allele ([TCTA]1[TCTG]1[TCTA]11), and the 15 STR allele identified as a null allele. Fetal sample B was found to contain both a 14 STR allele ([TCTA]14) and the 15 STR apparent null allele. Therefore, we concluded that both fetuses received the D8S1179 15 STR allele from the mother. Analyzing the sequence adjacent to D8S1179, in each of the alleles we identified a sequence variant in the genomic sequence flanking the 15 STR allele (Figure 3B). It was a guanine (G) to adenine (A) transition, 56 bp downstream of the STR (Figure 4)12 at position 143620 of reference sequence AF216771 (position 147 of reference sequence G08710). Because we were unable to separate the 15 STR D8S1179 allele from the other allele present in each sample, the change is heterozygous with the other allele present in each pictured sequence. It was because we were able to separate the 10 STR allele from the 15 STR allele in the maternal specimen that we were able to conclude with certainty that the sequence change was present in the genomic sequence flanking the 15 STR allele.

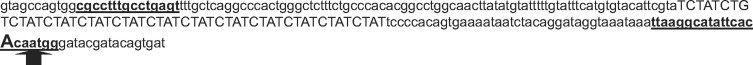

Figure 4.

Sequence variation in the genomic sequence (5′->3′) flanking the D8S1179 allele leads to allele dropout. Location of the D8S1179 STR locus is indicated by capitalization. Location of the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus primer set is indicated by an underline.12 The G to A sequence variation at bp 143620 of reference sequence AF216771 (position 147 of reference sequence G08710) found in the genomic sequence flanking the D8S1179 allele and causing allele dropout of the 15 STR allele in our patient's samples is indicated with an arrow.

We ultimately found the primer sequence for the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus D8S1179 loci published.15 The sequence change we identified in the genomic sequence flanking the 15 STR allele was located 16 bp removed from the 3′ end of the reverse primer (Figure 4).12

Discussion

In this study, we report a G to A sequence change in the genomic sequence flanking the D8S1179 STR that led to allele dropout in our maternal cell contamination assay. We tested twin fetal samples that carried a shared maternal allele in eight of nine STR loci by using the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus amplification kit (Applied Biosystems). At the D8S1179 STR, however, there was no amplifiable maternal allele in either of the fetal samples. This led us to hypothesize that either there could be an issue of “nonmaternity” such as could potentially be seen with the use of a donor egg from a closely related family member, or that a null allele was shared between the mother and the twins. Because both the mother and the fetuses demonstrated homozygosity at the D8S1179 locus, we investigated and confirmed that allele dropout had caused the discrepancy.

The G to A sequence change at bp 143620 of reference sequence AF216771 (position 147 of reference sequence G08710) that we identified as the cause for allele dropout in our samples at the D8S1179 marker has been previously described.10,11,13,16,17,18 The variant was reported most frequently in alleles between 15 and 18 repeats in length.17 The change appears to be pan-ethnic, having been reported in German,17 French,11 Korean,13 African,18 Chinese,10 and Chamorro and Filipino16 individuals. For those studies that screened large populations, individuals heterozygous for this change appear to be rare.10,11,17,18 However, the frequency of this sequence change can be higher in certain ethnic or geographic regions. For example, in 9% of Chamarro and Filipino individuals, it was found to be heterozygous.7,16

Concordance studies have demonstrated that STR allele dropout is rare with the use of commercially manufactured primers.7,10,11 However, D8S1179 shows an increased rate of allele dropout in certain populations when assayed by using the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus assay system.7,16 In our samples, the G to A bp variation that occurs 16 bp 5′ to the 3′ end of the D8S1179's reverse primer in the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus kit led to allele dropout. Because efficient priming is most dependent on bp matching at the 3′ end of the primer,8,9 we were surprised that a sequence variation closer to the 5′ end of the primer would lead to complete allele dropout. In the commercially available kits, primer sets are multiplexed and annealing conditions that amplify all amplicons are used. Optimized conditions for specific primers, therefore, are not necessarily applied. If the annealing temperature of the D8S1179 reverse primer included in the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus kit were decreased to 55°C, our null allele could be amplified.16 But in order for the PCR reactions to remain multiplexed in the kit, a degenerate primer was designed that matched the G to A sequence variation.16 The high frequency of this sequence change in the Chamorro and Filipino populations caused Applied Biosystems to add this degenerate primer as a second unlabeled reverse primer to their Profiler Plus Identifiler system. The degenerate primer was validated in the multiplex system and was shown to be able to amplify alleles containing the G to A sequence variation while simultaneously not adversely affecting the behavior of the system.15 Interestingly, this new primer was not added to the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus kit, but only to the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus ID (Identifiler) kit. Therefore, labs that use the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus kit will not amplify alleles containing the G to A sequence change. In our MCC determination, the presence of the null allele did not delay the reporting of the assay results because we already had three informative markers showing that the fetal samples did not contain maternally derived genetic material above the level of detection validated for our assay. However, had only two informative markers been present, we would have had to either issue an equivocal result or delay the reporting of the maternal cell contamination assay until further investigation could be performed. This delay would have been unacceptable given the time sensitive nature of the prenatal α thalassemia assay, which, because it was PCR based, was very dependent on the maternal cell contamination assay for interpretation. Therefore, it may be helpful if the degenerate primer, known to decrease the incidence of null alleles in the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus ID system, could be added to other Applied Bioscience STR assay systems, as well.

Point mutations in regions flanking the various STR loci can potentially lead to allele drop not just in the AMPF/STR Profiler Plus kit system, but in other commercially available and laboratory developed assays, as well. For example, D8S1179 allele dropout has also been reported with Promega's PowerPlex 16 assay system,17,19 due to a G to A transition in the region upstream of the STR.17 In addition, an A to T transversion downstream of the D8S1179 locus was determined to account for allele dropout in the Nonaplex I assay kit (Mentyoe Twin, Biotype AG, Dresden, Germany).17 Other STR loci are also susceptible to allele dropout using various commercial amplification systems.7,10,11,19 Overall, however, allele dropout is rare. With commercially available kits, an average allele dropout rate of approximately 0.2% to 0.5% has been reported.7,10,11 We conclude that, although this event is rare, when allele homozygosity at an STR locus is unexpected, the possibility of allele dropout must be considered.

References

- 1.Adamson D, Albertson H, Ballard L, Bradley P, Carlson M, Cartwright P, Council C, Elsner T, Fuhrman D, Gerken S, Harris L, Holik P, Kimball A, Knell J, Lawrence E, Lu J, Marks A, Matsunami N, Melis R, Milner B, Moore M, Nelson L, Odelberg R, Peters G, Plaetke R, Riley R, Robertson M, Sargent R, Staker G, Tingey A, Ward K, Zhao X, White R. A collection of ordered tetranucleotide-repeat markers from the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:619–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimpton CP, Gill P, Walton A, Urquhart A, Millican ES, Adams M. Automated DNA profiling employing multiplex amplification of short tandem repeat loci. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;3:13–22. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond HA, Jin L, Zhong Y, Caskey CT, Chakraborty R. Evaluation of 13 short tandem repeat loci for use in personal identification applications. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55:175–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urquhart A, Kimpton CP, Downes TJ, Gill P. Variation in short tandem repeat sequences: a survey of twelve microsatellite loci for use as forensic identification markers. Int J Legal Med. 1994;107:13–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01247268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler JM. Short tandem repeat typing technologies used in human identity testing. BioTechniques. 2007;43:ii–iv. doi: 10.2144/000112582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrijver I, Cherny SC, Zehnder JL. Testing for maternal cell contamination in prenatal samples: a comprehensive survey of current diagnostic practices in 35 molecular diagnostic laboratories. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:394–400. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budowle B, Masibay A, Anderson SJ, Barna C, Biega L, Brenneke S, Brown B, Cramer J, DeGroot G, Douglas D, Duceman B, Eastman A, Giles R, Hamill J, Haase D, Janssen D, Kupferschmid T, Lawton T, Lemire C, Llewellyn B, Moretti T, Neves J, Palaski C, Schueler S, Sguelia J, Sprecher C, Tomsey C, Yet D. STR primer concordance study. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;124:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00563-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petruska J, Goodman MF, Boosalis MS, Sowers LC, Cheong C, Tinoco I., Jr Comparison between DNA melting thermodynamics and DNA polymerase fidelity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6252–6256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dieffenbach CW, Lowe TM, Dveksler GS. General concepts for PCR primer design. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;3:S30–S37. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.3.s30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton TM, Hill SM, Denton LA, Watson SK, Urquhart AJ. Primer binding site mutations affecting the typing of STR loci contained within the AMPF/STR SGM Plus kit. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;139:255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delamoye M, Duverneuil C, Riva K, Leterreux M, Taieb S, De Mazancourt P. False homozygosities at various loci revealed by discrepancies between commercial kits: implications for genetic databases. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;143:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber MD, Parkin BH. Sequence analysis and allelic designation of the two short tandem repeat loci D18S51 and D8S1179. Int J Legal Med. 1996;109:62–65. doi: 10.1007/BF01355518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han GR, Song ES, Hwang JJ. Non-amplification of an allele of the D8S1179 locus due to a point mutation. Int J Legal Med. 2001;115:45–47. doi: 10.1007/s004140100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kotzot D. Complex and segmental uniparental disomy updated. J Med Genet. 2008;45:545–556. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotoz D. Prenatal testing for uniparental disomy: indications and clinical relevance. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:100–105. doi: 10.1002/uog.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leibelt C, Budowle B, Collins P, Daoudi Y, Moretti T, Nunn G, Reeder D, Roby R. Identification of a D8S1179 primer binding site mutation and the validation of a primer designed to recover null alleles. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;133:220–227. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hering S, Nixdorf R, Dressler J. Identification of more sequence variations in the D8S1179 locus. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;149:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alves C, Gusmao L, Damasceno A, Soares B, Amorim A. Contribution for an African autosomic STR database (AmpF/STR Identifiler and Powerplex 16 System) and a report on genotypic variations. Forensic Sci Int. 2004;139:201–205. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huel RL, Basic L, Madacki-Todorovic K, Smajlovic L, Eminovic I, Berbic I, Milos A, Pasons T. Variant alleles, triallelic patterns, and point mutations observed in nuclear short tandem repeat typing of populations in Bosnia and Serbia. Croat Med J. 2007;48:494–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]