Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the characteristics of older adults who develop elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels at three-year follow-up.

Design

Population based study of adults living in Tuscany, Italy.

Setting

Community

Participants

Adults aged ≥65 and were selected for this study. Out of 1155 baseline participants aged ≥65, a total of 741 had IL-6 measurements at baseline and three-year follow-up.

Measurements

The uppermost quartile of IL-6 was used as the threshold for defining elevated IL-6 (≥4.18pg/ml). Serum IL-6 levels were assessed by enzyme immunoassay.

Results

Among the 581 participants with IL-6 <4.18pg/ml at baseline, 106 (18.2%) developed elevated IL-6 at follow-up. Although women had lower IL-6 levels at baseline than men, the risk of developing elevated IL-6 did not differ by sex. Increased adiposity reflected by body mass index ≥30 (odds ratio [OR]=2.63, 95% confidence interval [CI]= 1.40-4.96) and high waist circumference (OR=2.05, 95% CI=1.24-3.40) were significant predictors of developing elevated IL-6 at follow-up. Other significant predictors were presence of ≥3 chronic diseases (OR=3.66, 95% CI=1.54-8.70), higher baseline IL-6 (OR=1.82, 95% CI=1.39-2.38), higher white blood cell count (OR=1.24, 95% CI=1.06-1.45), and walking speed (OR=0.83, 95% CI=0.74-0.92).

Conclusion

Older age, adiposity, slower walking speed, higher disease burden and white blood cell count were associated with increased risk of IL-6 elevation over a three-year period. Future research should target older adults with these characteristics to prevent progression to a pro-inflammatory state.

Introduction

Based on extensive research conducted in the past twenty years, there is wide consensus that inflammation contributes to the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. While transient inflammation is a normal process that promotes tissue repair and microbial resistance, the physiological changes that occur with inflammation become detrimental in the long term. In healthy individuals, immunomodulatory mechanisms tightly control the locale and duration of inflammation to promote the beneficial effects while minimizing damage. There is evidence that this immunomodulation is shifted during the aging process toward a pro-inflammatory state.

With increasing age, the blood levels of acute phase reactants and cytokines such as interleukin-6, interleukin-1ra, interleukin-18 and tumor necrosis factor α tend to increase (1, 2). The age-related pro-inflammatory state may be due to an intrinsic dysregulation of the immune system, although the increased burden of atherosclerosis also plays a role (3). Regardless of the cause of inflammation, elevated cytokines can contribute to the morbidity and/or pathogenesis of common age-related diseases including cardiovascular disease (4), diabetes mellitus (5), sarcopenia (6), and dementia (7).

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has been called a “cytokine for gerontologists” (8) because of its elevation with age and central roles in initiating and modulating inflammatory responses to injury and infection (9). Major sources of IL-6 are lymphocytes, skeletal muscle, vascular smooth muscle and adipocytes (10). Higher serum IL-6 is linked to increased rates of disability, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality (11-14). So far, most epidemiological analyses of IL-6 were conducted on limited numbers of subjects; in particular, very little data exists on longitudinal changes in the same individuals. To our knowledge, the factors associated with IL-6 elevation have not been prospectively analyzed in a large, representative population sample. Because IL-6 is so strongly associated with adverse outcomes in the older population, the identification of individuals susceptible to elevation of IL-6 is clinically important. In this study, data from the InCHIANTI study was used to identify predictors of IL-6 elevation over a three year period in older individuals.

Methods

Population

The InCHIANTI study is a representative cohort of community-dwelling older adults living in Tuscany, Italy. The overall baseline participation rate was 91.6% of all selected individuals. A total of 1155 adults aged 65 and older consented for a baseline assessment in 1998-2000. Of them, 1038 (90.0%) provided a baseline serum sample that was sufficient for IL-6 analysis.

At three-year follow-up, 741 (71.4%) of the 1038 baseline participants provided a sufficient blood draw for cytokine analysis. Of the 297 participants without follow-up cytokine data, 102 (34.3%) were lost to death in the intervening three years, 87 (29.0%) declined a blood draw, 19 (6.4%) had insufficient serum samples and the remaining subjects relocated or were lost to follow-up (n=90, 30.3%). Subjects with incomplete baseline or follow-up data were older, had higher chronic disease burden and were more likely to die in the subsequent 3 years. There were no sex differences in those excluded for incomplete data. Out of the 741 participants with complete IL-6 data, 160 were further excluded from the analysis due to high levels of IL-6 at baseline (4.18pg/ml was the threshold; see below for details). Those with higher baseline IL-6 were older, had greater chronic disease burden and were more likely to be male than those with lower baseline IL-6.

IL-6 Measurements

Venous blood was collected in the morning after a 12-hour fast. Baseline IL-6 immunoassays were performed by the INRCA laboratory (BioSource International Inc., Camarillo, CA). Follow-up IL-6 immunoassays were performed by the University of Vermont Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). Because of antibody and technique variations between the two institutions, measurements at baseline and follow-up could not be directly compared. Therefore, repeat IL-6 assays were conducted on 75 baseline samples at the University of Vermont (correlation coefficient 0.88) to transform the baseline values into values that are directly comparable with the follow-up results.

Past research has shown that risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality from CVD increased with IL-6 levels, with the most pronounced risk at the uppermost tertile or quartile of IL-6 (15-18). Based on these data, the upper quartile value of IL-6 at baseline (4.18pg/ml, using all available IL-6 values at baseline) was used as the cut point for defining high levels of this cytokine.

Diseases and other variable definitions

A variety of disease diagnoses and risk factors were used in this analysis. High waist circumference (WC) was defined by the World Health Organization as ≥102cm for men and ≥88cm for women (19). Body mass index (BMI) was divided into three categories: 18.5-24.9, 25-29.9 and ≥30 kg/m2 (19). Congestive heart failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (emphysema and/or chronic bronchitis), hip fractures and cancer were assessed by self-report of physician diagnoses, medications and laboratory findings, and/or physician examination following protocols validated in the Women's Health and Aging Study (20). Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥ 126mg/dL or treatment with anti-diabetic drugs and past diagnosis. Possible osteoporosis was assessed by peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) determination of distal tibia bone mineral density. Participants with densities 2.5 standard deviations below the mean density of a reference group aged 21-39 were considered to have osteoporosis; reference densities were determined separately for men and women (21). Renal impairment was defined as glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60mL/min/1.73m2 as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation: estimated GFR = 186×Scr-1.154×age-0.203×(0.742 if female) where Scr is serum creatinine. Hypertension was determined by self-report and treatment for hypertension or measured blood pressure ≥160mmHg for systolic blood pressure, or ≥90mmHg for diastolic blood pressure. Peripheral arterial disease was defined as ankle-brachial-index of less than <0.9 calculated from the leg with the lower blood pressure. A total disease burden score was created by counting the number of coexisting diseases in each participant. For participants able to ambulate (walking aides were permitted), usual 4-meter walk speed was carried out at a self-selected pace. Physical activity, education, and smoking status were assessed by self-report. Depression was defined as a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) score of ≥16 (22).

Analysis

Baseline characteristics of participants with and without elevated IL-6 at follow-up were compared using t-test or chi square test in Table 1. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the association of a variety of baseline variables with development of elevated IL-6 (Table 2). Model 1 examines the association of age, sex and baseline IL-6 with IL-6 elevation at follow-up. Model 2 examines the effect of each risk factor entered individually, adjusting for age, sex and baseline IL-6. Significant factors from Model 2 were carried over to Models 3, 4 and 5 which examine combinations of individually significant risk factors, with all models including age, sex and baseline IL-6.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics by IL-6 status at Three-year follow-up.

| IL-6 <4.18 at follow-up (n=475) | IL-6 ≥ 4.18 at follow-up (n=106) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % or mean | n | % or mean | P value | |

| Mean Age: | 475 | 72.6 | 106 | 75.9 | < .001 |

| Sex F | 268 | 56.4% | 68 | 64.2% | .145 |

| Education >5 yrs | 139 | 29.3% | 25 | 23.6% | .240 |

| Body mass index ≥ 30 | 116 | 24.5% | 40 | 37.7% | .006 |

| High waist circumference * | 184 | 39.8% | 57 | 55.3% | .004 |

| Depression | 72 | 15.2% | 27 | 25.5% | .011 |

| Currently smokes | 63 | 13.3% | 12 | 12.9% | .590 |

| Mean 4-m walk speed (m/s) | 1.11 | 0.23 (stdev) | 0.96 | 0.27 (stdev) | .008 |

| Mean baseline IL-6 (pg/ml) | 2.39 | 0.83 (stdev) | 2.83 | 0.79 (stdev) | < .001 |

| Mean white blood cell count (103/ul) | 5.79 | 1.25 (stdev) | 6.28 | 1.71 (stdev) | .001 |

| Baseline Diseases | |||||

| Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) | 9 | 1.9% | 6 | 5.7% | .145 |

| Stroke | 14 | 3.0% | 3 | 2.8% | .948 |

| Myocardial Infarct | 16 | 3.4% | 5 | 4.7% | .501 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 47 | 9.9% | 13 | 12.3% | .469 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 26 | 5.5% | 8 | 7.6% | .411 |

| Osteoporosis | 82 | 17.3% | 19 | 17.9% | .871 |

| Renal Impairment | 52 | 11.0% | 14 | 13.2% | .507 |

| Hypertension | 268 | 56.4% | 76 | 71.7% | .004 |

| Cancer | 29 | 6.1% | 8 | 7.6% | .583 |

| Hip fracture | 12 | 2.5% | 6 | 5.7% | .092 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 30 | 6.3% | 13 | 12.3% | .034 |

| Total Disease burden | |||||

| 0 | 118 | 20.3% | 11 | 10.4% | Test for trend: p = .001 |

| 1 | 246 | 42.3% | 43 | 40.6% | |

| 2 | 158 | 27.2% | 32 | 30.2% | |

| ≥3 | 59 | 10.2% | 20 | 18.9% | |

Participants with normal baseline IL-6 (<4.18pg/ml, n=581) were stratified into normal and elevated (≥4.18pg/ml) follow-up groups.

High waist circumference is defined as ≥102cm in men and ≥88cm in women.

Table 2. Multivariable predictors of developing elevated IL-6 at Three-year follow-up.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Age (per year) | 1.07 (1.04-1.11) | 1.04 (1.00-1.09) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 1.05 (1.00-1.09) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Women | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Men | 0.71 (0.45-1.12) | 0.94 (0.56-1.58) | 1.21 (0.69-2.13) | 1.11 (0.62-1.99) | ||

| Risk Factors: | ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| >5 yrs | 1.00 | |||||

| ≤5 yrs | 1.10 (0.65-1.87) | |||||

| Physical Activity | ||||||

| High activity | 1.00 | |||||

| Moderate activity | 1.52 (0.43-5.36) | |||||

| Sedentary | 1.96 (0.56-6.85) | |||||

| Smoking | ||||||

| never | 1.00 | |||||

| former | 1.54 (0.86-2.76) | |||||

| current | 1.20 (0.56-2.53) | |||||

| Depression | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 1.54 (0.89-2.67) | |||||

| Waist Circumference (WC) | ||||||

| Normal | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| High | 2.05 (1.24-3.40) | 1.88 (1.11-3.21) | 1.60 (0.84-3.04) | |||

| Body Mass Index | ||||||

| 18.5-24.9 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 25-29.9 | 2.21 (1.21-4.03) | 2.00 (1.05-3.80) | 1.75 (0.89-3.44) | |||

| ≥30 | 2.63 (1.40-4.96) | 2.11 (1.07-4.15) | 1.57 (0.70-3.56) | |||

| Total disease burden | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 2.03 (0.99-4.16) | 2.05 (0.92-4.57) | 2.07 (0.92-4.61) | 2.09 (0.93-4.69) | ||

| 2 | 1.96 (0.92-4.17) | 2.25 (0.97-5.21) | 2.24 (0.97-5.20) | 2.35 (1.01-5.47) | ||

| ≥3 | 3.66 (1.54-8.70) | 2.99 (1.13-7.94) | 2.87 (1.10-7.48) | 3.19 (1.20-8.50) | ||

| White blood cell count (103/μl) | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) | 1.20 (1.01-1.43) | 1.20 (1.01-1.43) | 1.20 (1.00-1.42) | ||

| 4-m walk speed (per 0.1m/s) | 0.83 (0.74-0.92) | 0.87 (0.78-0.97) | 0.86 (0.76-0.96) | 0.87 (0.77-0.97) | ||

| Baseline IL-6 (per 1.0 pg/ml) | 1.82 (1.39-2.38) | 1.80 (1.33-2.42) | 1.81 (1.35-2.45) | 1.83 (1.36-2.48) | ||

Model 1 adjusts for age, sex and baseline IL-6. Model 2 represents multiple regressions, each regression examines an individual risk factor adjusting for age, sex and baseline IL-6. Models 3, 4, 5 simultaneously examine combinations of individually significant risk factors adjusting for age, sex, and baseline IL-6.

Results

Baseline characteristics associated with development of elevated IL-6

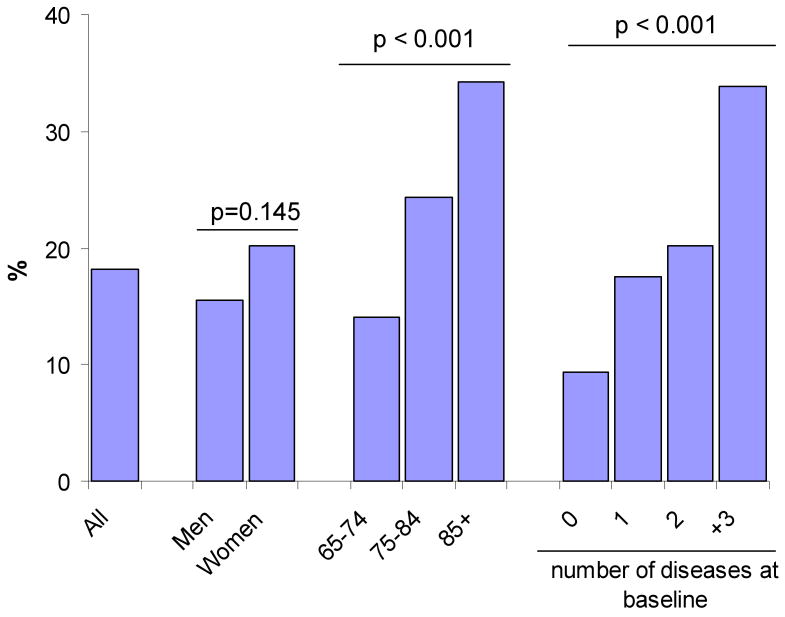

Among the 581 participants with IL-6 <4.18pg/ml at baseline, 106 had IL-6 ≥4.18pg/ml at three-year follow-up (elevation rate = 18.2%). Figure 1 shows the rates of IL-6 elevation by sex, age and disease burden. Although women on average had lower baseline IL-6 values, they were just as likely as men to develop elevated IL-6 at follow-up. Rates of developing elevated IL-6 increased with higher age and disease burden.

Figure 1.

Development of IL-6 Elevation by Baseline Characteristics

Development of elevated IL-6 at follow-up according to baseline demographic and disease characteristics, n is shown in parenthesis. Development of elevated IL-6 is defined as having normal IL-6 levels at baseline (<4.18pg/ml, n=581) and elevated IL-6 at follow-up (≥4.18pg/ml, n=106). The overall elevation rate was 18.2%. Diseases included were congestive heart failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoporosis, renal impairment, hypertension, cancer, hip fracture and peripheral arterial disease.

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of participants by IL-6 status at follow-up. Participants who developed elevated IL-6 at follow up were significantly older, reported more depressive symptoms, had higher baseline IL-6 and white blood cell (WBC) counts, and were more likely to have BMI ≥30 and a high waist circumference than those who did not have elevated IL-6 at follow-up. Mean walking speed was significantly slower in those who developed elevated IL-6 at follow-up than those who remained below the threshold. Baseline hypertension, peripheral arterial disease and total disease burden were significantly associated with development of elevated IL-6 at follow-up.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for IL-6 elevation at follow-up

In Table 2, the strongest individual predictors of IL-6 elevation were age, BMI, WC, total baseline disease burden, walking speed, WBC count, and baseline IL-6 levels after adjusting for age and sex (model 2). The association of age with elevated IL-6 in model 1 was reduced when other risk factors were included in models 3-5. In models 3 and 4, BMI and WC were each significant predictors of elevated IL-6 at follow-up. However, neither were significant when both variables were included in model 5, indicating co-linearity between the two factors. In all models, higher disease burden, slower walking speed and higher WBC counts were significantly associated with greater likelihood of developing elevated IL-6.

A more detailed examination of disease status and development of elevated IL-6 was carried out (data not shown). Participants were categorized one of three groups: a group free of disease at baseline and follow-up, a group with prevalent disease at baseline, and a group with incident disease onset between baseline and follow-up. After adjusting for age, sex and baseline IL-6, participants with new onset stroke and new onset diabetes mellitus were significantly more likely to have elevated IL-6 at follow-up than participants who remained free of these diseases. Hypertension was the only prevalent condition significantly associated with IL-6 elevation.

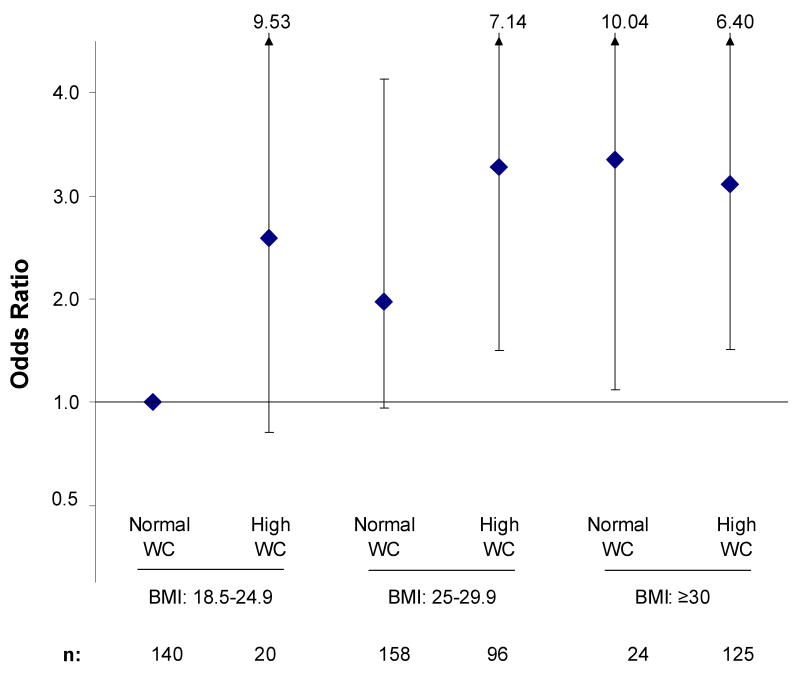

Joint effects of BMI and WC on IL-6 elevation at follow-up

The joint effect of BMI and WC on IL-6 elevation at three-year follow-up is shown in Figure 2. Participants with BMI ≥30 were about three times more likely to develop elevated IL-6 at follow-up regardless of WC. For participants with BMI 25-29.9, only those with high WC were significantly more likely to develop elevated IL-6. Participants with BMI of 25-29.9 and normal WC and those with BMI of 18.5-24.9 and high WC had about a 2 to 3-fold increased risk for developing elevated IL-6, although these relationships were not statistically significant possibly due to small sample size.

Figure 2.

Joint Effect of Body Mass Index and Waist Circumference on IL-6 Elevation

Odds ratios for developing elevated IL-6 at follow-up according to body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC). Odds ratios were adjusted for age, sex and baseline IL-6. * Total N adds up to 563 rather than 581 due to missing BMI or WC data for some participants.

Recovery from elevated IL-6

Converse to elevation of IL-6, a substantial number of people also recovered from high baseline IL-6 (data not shown). Among the 160 people with high baseline IL-6, 81 (50.6%) of them recovered to <4.18pg/ml at follow-up. Those who recovered were younger than those who did not recover (mean ages 74.2 and 77.8 respectively) and had less average disease burden (1.08 vs 1.32 diseases, respectively). This shows that although the older population has a high prevalence of elevated IL-6, there is still strong potential for recovery. The factors tied to successful recovery are unclear and should be further studied in a larger cohort of persons with elevated IL-6.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to characterize older individuals at risk for developing elevated IL-6. The overall rate of developing elevated IL-6 over a three-year period was 18.2% in a representative older cohort. Predictors of elevation included different measures of adiposity, multiple co-morbidities, walking speed, baseline IL-6 and WBC count. These predictors each remained independently significant after adjusting for age and sex. Excluding participants with acute infection, antibiotic use, recent hospitalization, high white blood cell count (>11,000/ul) or newly diagnosed cancer did not significantly affect the results.

Body composition indirectly measured by BMI and WC were significant predictors after adjusting for other risk factors (Table 2, models 3 and 4). High BMI tends to reflect increased total body fat and WC is a reflection of visceral abdominal adiposity (23). These two measurements together provide information about both total fat and fat distribution. In the group with high IL-6 at follow-up, 37.7% had BMI ≥30 and 55.3% had high WC whereas in the group without high IL-6, 24.5% had BMI ≥30 and 39.8% had high WC. The odds of having elevated IL-6 at follow-up were more than tripled for participants with BMI ≥30 (regardless of waist size) compared to participants with BMI 18.5-24.9 and normal WC. In participants with BMI 25-29.9, only those with high waist circumference had a significantly higher likelihood of developing elevated IL-6. These results suggest that both visceral fat and non-visceral fat contribute to increased risk for inflammation in agreement with results from more refined measures of body fat. In the Framingham Study, visceral and subcutaneous fat assessed by computed tomography were linked to elevated inflammatory markers and signs of excessive oxidative stress (24). Given that adipose tissue is an important source of IL-6 (10), it may be hypothesized that the elevation of IL-6 at follow-up in participants with high BMI and WC is due to increased production of IL-6 from adipocytes and immune cells. The key role of IL-6 as a stimulator of the acute phase response and other immune functions may be the cause of elevated CRP and other inflammatory cytokines seen in participants with high adiposity (25).

Disease burden was another significant predictor of IL-6 elevation at follow-up. Participants at baseline with three or more chronic diseases were three times more likely to have elevated IL-6 at follow-up (Table 2) than those without diagnosed diseases. On the other hand, only a few specific diseases were associated with development of elevated IL-6 suggesting that total disease burden better reflects health status and homeostatic reserve than existence of any one specific disease. Walking speed, which captures the overall impact of chronic diseases, was also a significant factor. Each 0.1m/s increase in walking speed was associated with more than a 10% decline in the risk of developing elevated IL-6 at follow-up (Table 2). Moreover, walking speed remained significantly associated after adjusting for BMI or WC, total disease burden, baseline IL-6 and WBC count (Table 2, models 3-5). Walking speed appears to capture important impairments and subclinical conditions that contribute to development of inflammation not expressed by the other assessments. Previous research has shown that baseline IL-6 is cross-sectionally and longitudinally linked to lower physical performance and disability in the InCHIANTI cohort (13, 14). Overall, these relationships illustrate that physical performance not only reflects inflammatory status, but is also predictive of developing future inflammation. For geriatricians, simple measures of physical performance can reveal important clues about the impacts of clinical and subclinical diseases, inflammatory status and development of new inflammation.

InCHIANTI encompasses an extraordinary set of measures; it assesses a large, representative sample of older people without sacrificing comprehensive interview, medical and laboratory data for each participant. The detailed cross-sectional and longitudinal data facilitate examination of changes in the population. Cross-sectional data can reveal associations but cannot be used to delineate whether inflammation is a cause or result of various factors. This prospective analysis provides a better vantage point to study the potential causes that contribute to inflammation. This study also benefits from detailed ascertainment of a wide range of diseases following validated protocols as well as assessment of disease by a geriatrician's examination. The relatively large sample size in this study adds strength to the results. The substantial number of participants excluded due to missing follow-up IL-6 may be a source of bias (18.8%, n=195, not counting those lost to death) as they tended to be older and have higher disease burden.

Conclusion

Chronic inflammation has been associated with common aging-related diseases and their related morbidity and mortality in past research. This study shows that in community-dwelling older adults, the three-year rate of developing elevated IL-6 is 18.2% in a representative Italian cohort. Predictors of IL-6 elevation at follow-up were BMI, WC, higher total disease burden, walking speed, baseline IL-6 and WBC count. These factors may be possible targets of interventions aimed at preventing the development of chronic pro-inflammatory state in older individuals and their consequences.

Acknowledgments

The InCHIANTI Study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (ICS 110.1 RS97.71), by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (contract numbers: N01-AG-916413, N01-AG-821336, 263 MD 9164 13 and 263 MD 821336) and in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH, USA. All authors with significant contributions have been listed.

Funding sources:

The InCHIANTI Study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (ICS 110.1 RS97.71), by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (contract numbers: N01-AG-916413, N01-AG-821336, 263 MD 9164 13 and 263 MD 821336) and in part by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH, USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

| Elements of Financial/Personal Conflicts | Author 1 Shu-Han Zhu |

Author 2 Kushang Patel |

Author 3 Stefania Bandinelli |

Author 4 Luigi Ferrucci |

Author 4 Jack Guralnik |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Employment or Affiliation | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Grants/Funds | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Honoraria | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Speaker Forum | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Consultant | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Stocks | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Royalties | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Expert Testimony | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Board Member | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Patents | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Personal Relationship | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

Author Contributions:

Shu-Han Zhu: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation

Kushang Patel: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript preparation

Stefania Bandinell: study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data

Luigi Ferrucci: study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data

Jack Guralnik: study design, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data

Sponsor's Role: None

Bibliography

- 1.Brüünsgaard H, Pedersen BK. Age-related inflammatory cytokines and disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2003;23(1):15–39. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8561(02)00056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krabbe KS, Bruunsgaard H, Hansen CM, et al. Ageing is associated with a prolonged fever response in human endotoxemia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8(2):333–338. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.2.333-338.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrucci L, Corsi A, Lauretani F, et al. The origins of age-related proinflammatory state. Blood. 2005;105(6):2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106(5):502–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vettor R, Milan G, Rossato M, et al. Review article: adipocytokines and insulin resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Nov;22(Suppl 2):3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaap LA, Pluijm SM, Deeg DJ, et al. Inflammatory markers and loss of muscle mass (sarcopenia) and strength. Am J Med. 2002;119(6):e9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyss-Coray T. Inflammation in Alzheimer disease: driving force, bystander or beneficial response? Nat Med. 2006;12(9):1005–1015. doi: 10.1038/nm1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erschler WB. Interleukin-6: a cytokine for gerontologists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(2):176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1993.tb02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maggio M, Guralnik J, Longo DL, et al. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: a magnificent pathway. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(6):575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snick JV. Interleukin-6: An Overview. Annual Review of Immunology. 1990;8:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alley DE, Crimmins E, Bandeen-Roche K, et al. Three-year change in inflammatory markers in elderly people and mortality: the Invecchiare in Chianti study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1801–1807. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cesari M, P B, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Inflammatory Markers and Onset of Cardiovascular Events: Results From the Health ABC Study. Circulation. 2003;108(19):2317–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cesari M, P B, Pahor M, Lauretani F, Corsi AM, Rhys Williams G, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Inflammatory markers and physical performance in older persons: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59(3):242–248. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM, et al. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(6):639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesari M, P B, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Tracy RP, Rubin SM, Harris TB, Pahor M. Inflammatory markers and cardiovascular disease (The Health, Aging and Body Composition [Health ABC] Study) Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(5):522–528. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00718-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauchhaus M, Doehner W, Francis DP, et al. Plasma cytokine parameters and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;103(25):3060–3067. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107(11):1486–1491. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057810.48709.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volpato S, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, et al. Cardiovascular disease, interleukin-6, and risk of mortality in older women: the women's health and aging study. Circulation. 2001;103(7):947–953. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.7.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. Consultation on Obesity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, et al., editors. The Women's Health and Aging Study: Health and Social Characteristics of Older Women with Disability. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Aging; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. Guildelines for Preclinical Evaluation and Clinical Trials in Osteoporosis. World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Allison DB, et al. Body mass index and waist circumference independently contribute to the prediction of nonabdominal, abdominal subcutaneous, and visceral fat. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(4):683–688. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pou KM, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue volumes are cross-sectionally related to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116(11):1234–1241. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.710509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinrich PC, Castell JV, Andus T. Interleukin-6 and the acute phase response. Biochem J. 1990;265(3):621–636. doi: 10.1042/bj2650621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]