Abstract

The rotavirus inner capsid particle, known as the “double-layered particle” (DLP), is the “payload” delivered into a cell in the process of viral infection. Its inner and outer protein layers, composed of VP2 and VP6, respectively, package the eleven segments of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) of the viral genome, as well as about the same number of polymerase molecules (VP1) and capping-enzyme molecules (VP3). We have determined the crystal structure of the bovine rotavirus DLP. There is one full particle (outer diameter ~700 Å) in the asymmetric unit of the P212121 unit cell, of dimensions a= 740 Å, b= 1198 Å, c= 1345 Å. A three-dimensional reconstruction from electron cryomicroscopy was used as a molecular-replacement model for initial phase determination to about 18.5 Å resolution and the sixty-fold redundancy of the icosahedral particle symmetry allowed phases to be extended stepwise to the limiting resolution of the data (3.8 Å). The structure of a VP6 trimer (determined previously by others) fits the outer-layer density with very little adjustment. The T=13 triangulation number of that layer implies that there are four and one-third VP6 trimers per icosahedral asymmetric unit. The inner layer has 120 copies of VP2 and thus two per icosahedral asymmetric unit, designated VP2A and VP2B. Residues 101-880 fold into a relatively thin, principal domain, comma-like in outline, shaped such that only rather modest distortions (concentrated at two “subdomain” boundaries) allow VP2A and B to form a uniform layer with essentially no gaps at the subunit boundaries, except for a modest pore along the fivefold axis. The VP2 principal domain resembles those of the corresponding shells and homologous proteins in other dsRNA viruses: λ1 in orthoreoreoviruses, VP3 in orbiviruses. Residues 1-80 of VP2A and VP2B fold together with four other such pairs into a “fivefold hub” that projects into the DLP interior along the fivefold axis; residues 81-100 link the ten polypeptide chains emerging from a fivefold hub to the N-termini of their corresponding principal domains, clustered into a decameric assembly unit. The fivefold hub appears to have several distinct functions. One is to recruit a copy of VP1 (or of a VP1–VP3 complex), potentially along with a segment of (+)-strand RNA, as a decamer of VP2 assembles. A second is to serve as a shaft around which can coil a segment of dsRNA. A third is to guide nascent mRNA, synthesized in the DLP interior by VP1 and 5′-capped by the action of VP3, out through a fivefold exit channel. We propose a model for rotavirus particle assembly, based on known requirements for virion formation together with the structure of the DLP and that of VP1, determined earlier.

Keywords: double-layered particle, double-stranded RNA, virus assembly, icosahedral symmetry

Introduction

Viruses with double-strand RNA (dsRNA) genomes are found among the infectious agents of animals, plants, yeasts, and bacteria 1. Except for some dsRNA viruses of bacteria and fungi, the virions are generally multi-layered, icosahedrally symmetric, non-enveloped particles. Despite the huge diversity of their hosts, these viruses share a number of genomic and structural characteristics, including a form of the virus particle (in most cases, a subviral particle stripped of one or more outer shells) that becomes a transcriptionally active, mRNA-producing “molecular machine” when transferred to the cytoplasm of a host cell.

The transcriptionally active, inner capsid particle (ICP) of these viruses has various designations, depending on the history of nomenclature for the particular group of dsRNA viruses in question. The ICPs of orthoreoviruses and orbiviruses are known as “core” particles; those of rotaviruses, “double-layer” particles (DLPs). The crystal structures of the reovirus and orbivirus cores and of the yeast L-A virus have been described 2; 3, as have cryoEM reconstructions of several other dsRNA particles, at various resolutions 4; 5; 6; 7. All but the birnaviruses 8 appear to have in common a shell, composed of 120 copies of a related but quite variable protein, immediately surrounding the tightly coiled dsRNA. Other components can be quite different. For example, orthoreovirus cores (like the ICPs of aquareoviruses and oryzaviruses) have projecting, fivefold “turrets”, which are the capping enzymes that modify viral mRNA as it passes out of the particle 2.

We report here the crystal structure of the rotavirus DLP, determined with data that extend to a minimum Bragg spacing of 3.8 Å. The DLP inner shell protein is called viral protein 2 (VP2). A layer of VP6 trimers9, organized in a T=13l icosaheral lattice, surrounds the 120-subunit VP2 layer. Within the VP2 shell are 11 genomic segments, varying in length from ~700 to ~3100 nucleotide pairs, and 11 or 12 copies each of the viral polymerase, VP1, and the viral capping enzyme, VP3. These last two components are not detected in the crystal structure.

Results

Structure determination

The specific procedures, experimental and computational, for the crystallographic structure determination are described in the Materials and Methods section. The crystals, in space group P212121, a= 740 Å, b= 1198 Å, c= 1345 Å, contain a full particle per asymmetric unit. The 60-fold non-crystallographic redundancy permitted robust extension of low resolution phases from an 18.2 Å resolution cryoEM-based map to the full 3.8 Å resolution of the data; it also allowed us to overcome substantial diffraction anisotropy. We could trace the VP2B polypeptide chain from residue 81 to the C-terminus at residue 880 without much difficulty, and likewise, residues 100-800 in VP2A; VP2A residues 81-100 were not as well defined, but we could follow the path of the main chain. We could also identify residues 18-31 in an α-helix clustered near the fivefold axis with four symmetry mates, part of the inward-projecting feature we call the “fivefold hub”. The known structure of VP6 could be placed in the map with only local adjustments.

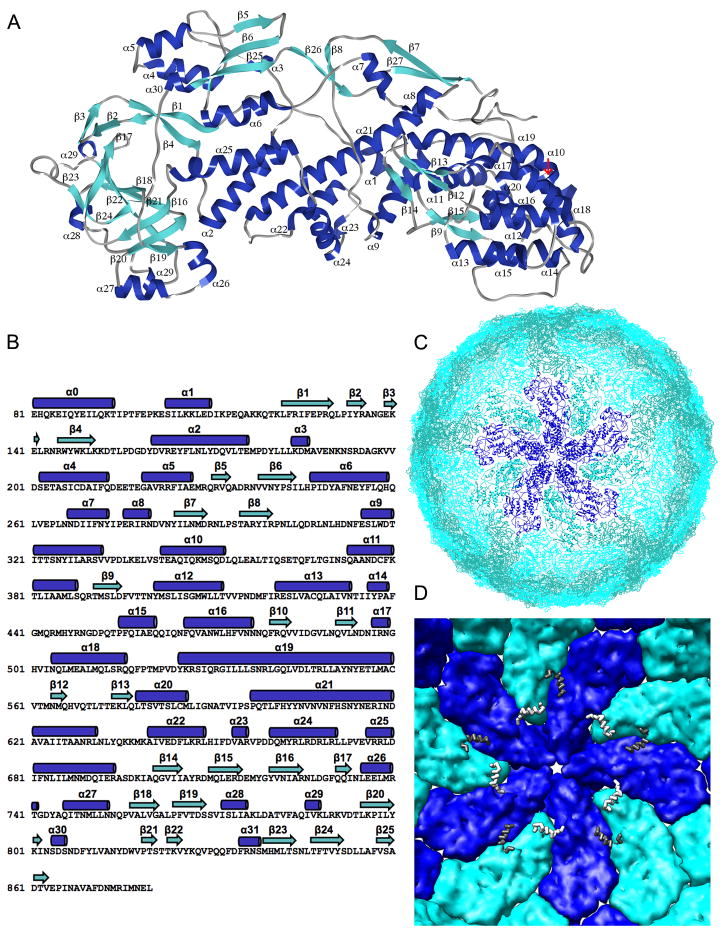

VP2

Most of the VP2 polypeptide chain folds into a broad, plate-like structure with a somewhat bean-shaped or inverted comma-shaped outline, 140 Å long by 60 Å wide and varying in thickness from 15–30 Å (Fig. 2A,B). Five monomers of VP2 (conformer A: VP2A) form a star-like complex about each fivefold axis, and five additional VP2 monomers (conformer B: VP2B) pack into the gaps between the points of the star. Twelve of the decamers thus formed make up the shell of the ICP (Fig. 2C). Of the 880 residues in the polypeptide chain, only those from 81–880 can be traced clearly. Residues 81-100 of VP2B form a loop and a helix that pack beneath a neighboring VP2A; density extending inward from residue 100 of VP2A indicates that a similar loop-helix element is present, but not as firmly fixed by its contacts with a neighboring subunit (Fig. 2D). Additional density features surrounding the fivefold axis at smaller radii show that the N-terminal segments of VP2A and B form a distinct, hub-like assembly (see below).

Fig 2.

Stucture of VP2. A. Ribbon representation, with secondary structural elements labeled. Helices in dark blue; strands in light blue. B. Amino-acid sequence (single-letter code) of UK Bovine VP2 (serogroup A) with secondary structural elements shown above the sequence. C. The VP2 shell, viewed from outside the particle into the 5-fold channel. The central decamer is highlighted, with VP2A in dark blue and VP2B in light blue. D. Internal view of the VP2 shell, represented as a surface rendering with colors for VP2A and B as in panel C. Residues 81-100 (the last parts of the N-terminal arms) are represented, respectively, by white and gray “worms”.

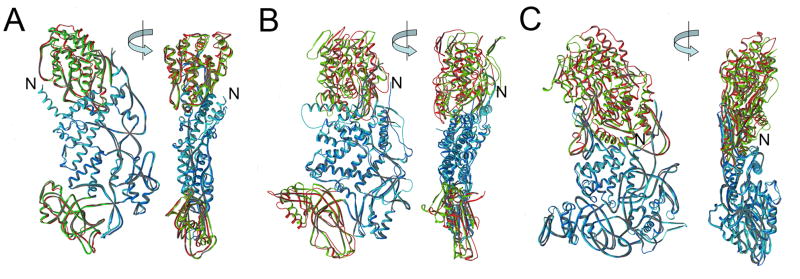

The shape of the VP2 subunit is such that relatively little distortion of one conformer is needed to create the other. Comparison of the A and B conformers suggests the following description of the internal flexibility in VP2. If one divides the subunit into three regions, then there are modest hinge motions at the two inter-regional boundaries (Fig. 3). We designate these three regions as “apical”, “central”, and “dimer-forming” (see Fig. 2C). If the middle regions of the two conformers are aligned, the rms deviations of the alpha carbon atoms in the apical regions is 4.7Å and that of the alpha carbons in the dimer-forming regions is 7.9Å (Fig. 3A).

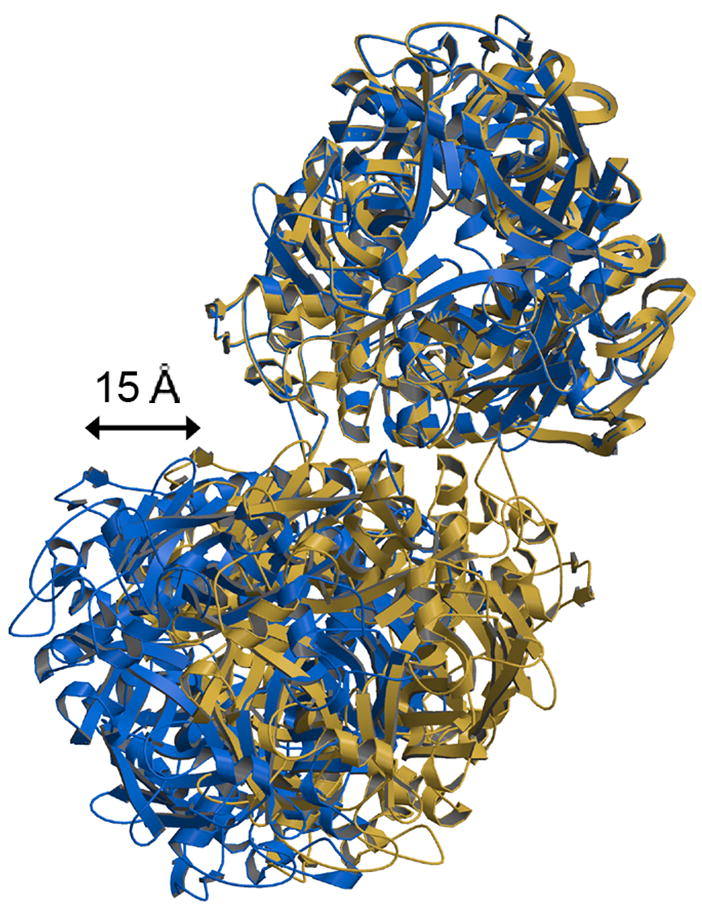

Fig 3.

Conformational flexibility of VP2 and VP2-like proteins: rotavirus VP2 (this work), BTV VP3 3 and reovirus λ1 2. In each panel, there are orthogonal views of the monomer closer to the 5-fold (e.g., VP2A), in red and dark blue, superposed on the monomer farther from the 5-fold (e.g., VP2B), in green and light blue. The proteins were aligned on their central domains. Rotavirus VP2 and BTV VP3 each have similar relative shifts of their dimer-forming domains (lower part of each figure; rmsd 2.4 Å and 4.7 Å, respectively), but substantially different shifts of their apical domains (upper part of each figure; 2.1 Å and 7.9 Å, respectively). λ1 has only two domains, with an rmsd of 5.4 Å of one when the other is aligned.

The structure of VP2 resembles, as expected, those of homologs in other dsRNA, viruses 2; 3, but each of the known exemplars has special features, and it is not evident from casual inspection how best to align them. Comparison of secondary structural elements shows that the principal helices and sheets in the central and apical regions are conserved (Fig. 3). This conserved core is decorated with additional elements, some of which are common to a subset of the proteins and some of which are unique insertions into the basic structure. Rotavirus VP2 appears to have the smallest number of insertions. Despite low sequence identity (<10%) among these proteins, alignment of VP2 to the other structures yields root-mean squared positional deviations of less than 5 Å for 80% of each polypeptide chain. Descriptions of the relationships between the two conformers are similar for the three examples shown in Fig. 3, although in the case of reovirus λ1, there appear to be only two independently superposable regions, with a hinge discontinuity in the middle of the subunit.

The inward face of the VP2 shell is of roughly uniform radius (240±5 Å), except for the internal projections near the fivefold axes and the segments of polypeptide chain (residues 81-100) leading into them. The charge distribution is unremarkable, with a slight excess of negatively charged side chains. The capsid thus presents to the genomic RNA a boundary surface that is relatively smooth, in both its steric and its electrostatic features (Fig. 2D).

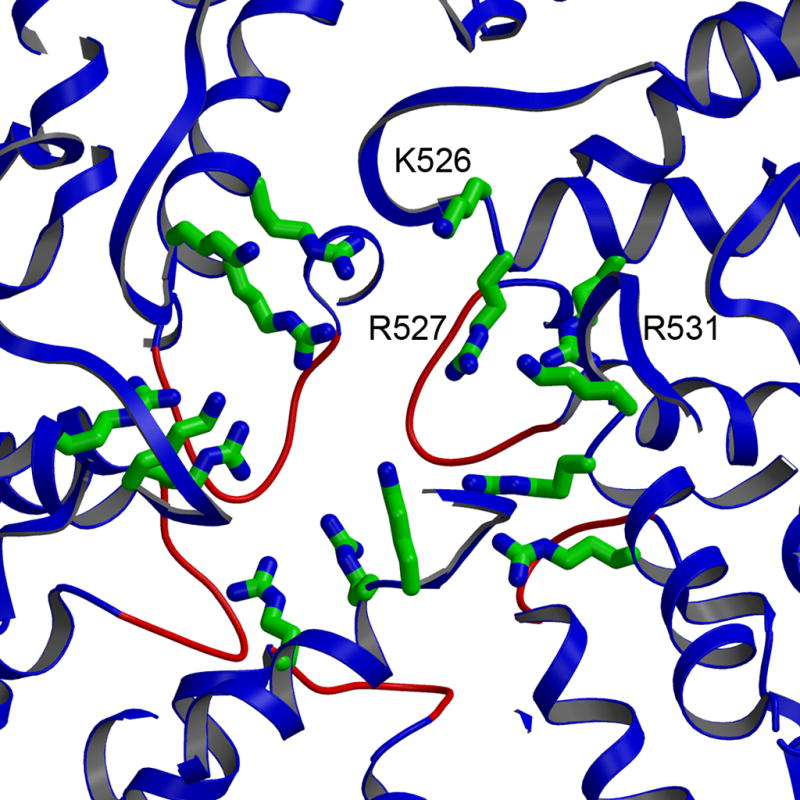

The convergence of five VP2A subunits around a fivefold axis leaves only a relatively small pore, lined with positive charge (Fig. 4). Flexion of the loops that impinge on this pore would be needed for RNA transcripts to pass through. Some differences in these loops in both VP2A and VP2B suggest that they can indeed adopt alternative conformations.

Fig 4.

The five-fold channel formed by VP2A monomers (backbone ribbons), with key conserved positively charged residues (Lys526, Arg527 and Arg531) shown as ball-and-stick representations. The VP2 loops (residues 354 to 363) that form an internal gate are highlighted in red.

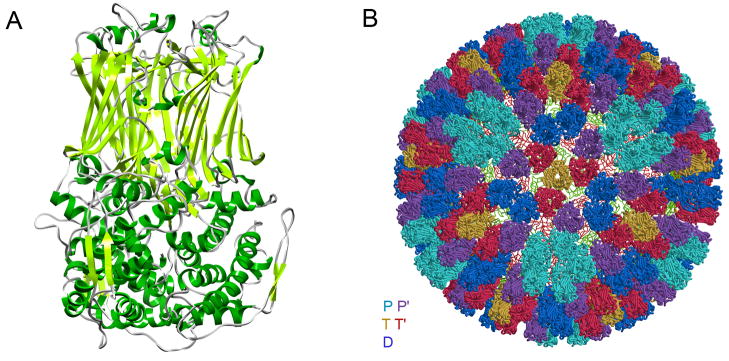

VP6

The VP6 subunit is a jelly-roll β-barrel with radially directed strands and with N- and C-terminal extensions that together form a largely α-helical pedestal (Fig. 5A)9. Both domains participate in very extensive trimer contacts. There are five distinct positions for the trimer on the outer surface of the ICP. They are designated T, T′, P, P′, and D in Fig. 5B. Only the first of these (T) lies on a particle threefold axis. The conformation of VP6 in each of the five locations is essentially the same as in crystals of the free trimer, with the exception of some variation in the segment containing residues 64-71, which is a principal contact with VP2.

Fig 5.

Structure and packing of VP6. A. Ribbon representation 9. B. The VP6 shell: 260 VP6 trimers are colored relative to their positions with respect to the icosahedral symmetry axes: gold (T, on the 3-folds), red (T′, adjacent to T), dark blue (D, closest to the 2-folds), light blue (P, closest to the 5-folds), and purple (P′, adjacent to P). The inner VP2 layer is shown in red and green coils.

The inter-trimer contacts have local two-fold character, as expected from their quasi-equivalent packing. Because the trimers project radially, the contacts involve residues in the pedestal domain, not in the apical β-barrel. There are seven distinct trimer-trimer contacts, one of which is across a strict icosahedral dyad (D-D in Fig. 5). They are all of modest extent, resembling more the interfaces within protein crystals than those within tightly knit assemblies. At five of the seven, the loops containing residues 142-146 approach each other across the local twofold, and a small network of polar interactions links the apposed trimers (Fig. 6B). The contributing residues, Gln 142, Asn 143, and Arg 145, are conserved in serogroup A and C rotavirus strains (see, for example, 10), as is Asp 380, which salt bridges to Arg 145. Also conserved are the partners in an additional salt bridge, somewhat displaced from the local twofold but at about the same radial position, between Arg 106 and Glu 353. Two of the trimer contacts have alternative salt-bridge patterns. At the D-P′ interface, the apposed trimers are displaced laterally by about 10 Å, with respect to their relative positions at the five nearly invariant interfaces, and Arg106 (now close to the local twofold) interacts with Glu 379, Asp 380, and Gln 383 (Fig. 6C). The P-P interface is distinctive, because thickening of the VP2 layer near the fivefold displaces the P trimers radially outward and tips the trimer threefold axes away from the fivefold (Fig. 6D). At these contacts, Arg 106 engages in a salt bridge with Glu 332 (and perhaps also with Glu 379), while the 142–146 loops are slightly displaced from each other. Thus, the adaptability of salt bridges between relatively long and conserved side chains (Arg and Glu) permits quasi-equivalent adjustments at five of the inter-trimer interfaces, while ion-pair switching among conserved alternatives occurs at the remaining two. Comparison of the VP6 trimer structure with a moderate resolution cryoEM reconstruction has led to similar, though less detailed, conclusions9.

Fig 6.

Alternative juxtapositions of VP6 trimers across local twofold axes in the T=13 icosahedral lattice. The interfaces between T and P′ and T and D (blue) show a relative shift of ~15 Å relative to those between T and T and T and T′ (tan). T-T has been aligned to T-D. Despite this shift, similar residues interact at the trimer interface, generating a set of alternative salt bridges, as described in the text.

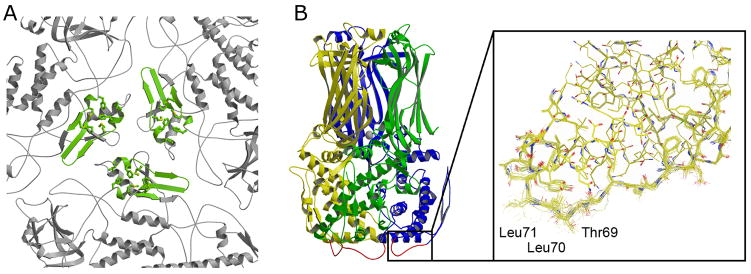

VP2-VP6 contacts

The principal interaction is between the inward-projecting β2-α3 loop (residues 64-72) of VP6 and the outer surface of VP2. The β2-α3 loop, an extended segment of polypeptide chain that runs alongside two α-helices, manages to adjust to the 13 distinct VP2 locations that it faces so that the side chains of Thr69 and Leu71 make some sort of van der Waals contact in each. The most intimate contact occurs beneath VP6-T: the side chains of Thr69 and Leu71 fit into a pocket formed by Met228, Met839, Met841, Phe244, and Ala220 of VP2B (Fig. 7). The corresponding pocket on the surface of VP2A receives the side chains of Leu70 and Leu71 from one of the three subunits of VP6-D. Beneath VP6-P′, one of the β2-α3 loops has no contact with the VP2 layer, but the other two, and the intervening surface, have very extensive interaction with VP2B, including a network of hydrogen bonds among side-chain and main-chain polar groups from both VP6 and VP2 and van der Waals contacts that include Leu65, Thr68, Thr69, and Leu 71 on one or both of the two VP6 monomers. Analysis of virus-like particles (VLPs) generated with wild-type VP2 shows that any VP6 double mutant that contains a polar residue at Leu71 and a polar residue at either Leu70 or Leu65 fails to incorporate stably11.

Fig 7.

Interactions of VP6 and VP2. A. View of the VP2 layer directly along the icosahedral 3-fold, highlighting (in green) residues that have direct contacts with the VP6 trimer bound over them. A hydrophobic pocket on the surface of VP2 (side chains shown) receives a loop from VP6 (residues 65 to 72). B. Detailed view of this loop, which can adopt any of several conformations, depending on the part of the VP2 surface it contacts; it is represented here in the conformation it adopts when interacting with the hydrophobic pocket shown in A.

Only VP6-T has three identical contacts with VP2, and we can therefore expect it to be the most firmly attached. Indeed, the overall thermal parameter (B-factor) for VP6 is lowest for VP6-T and increases for trimers near the fivefold (Fig. 8). There is a similar gradient in the BTV core 3. The β2-α3 loop of VP6-P is displaced from VP2, leaving a “tunnel” beneath the ring of VP6-P trimers, which are retained in the ICP only by VP6-VP6 contacts. In rotavirus strain Wa, these peripentadic trimers dissociate from transcriptionally competent ICPs 12. It is plausible to suppose that assembly of the VP6 layer on the surface of VP2 proceeds from the threefold, rather like a two-dimensional crystallization. Some of the VP6-VP6 contacts in the DLP also appear to be present in tubular VP6 assemblies, an alternative surface lattice of VP6 trimers 13.

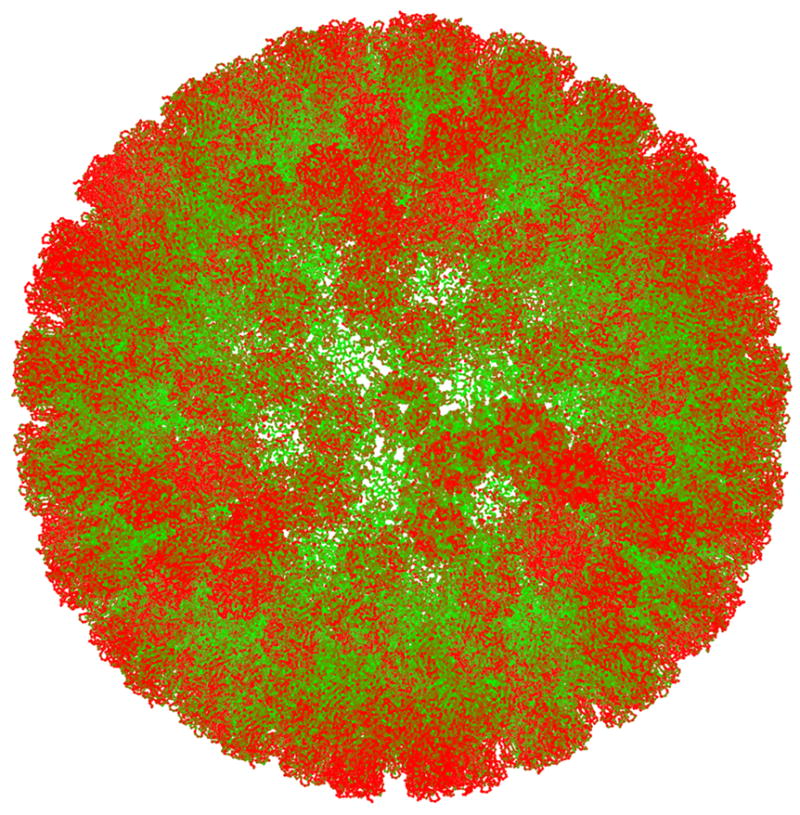

Fig 8.

View of the ICP surface, colored by B-factor (low to high, green to red, respectively). The degree of disorder increases with radial position in the particle and with distance within the surface from the nearest icosahedral 3-fold axis.

Internal structures

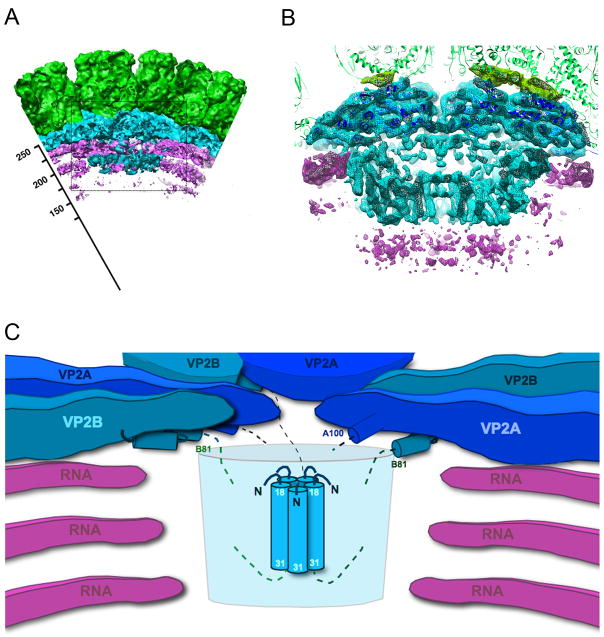

The capsid defined by residues 81-880 of VP2 encloses a volume of 58×106 Å3, which must contain the eleven viral RNA segments, 11–12 copies each of VP1 and VP3, and the N-terminal parts of the VP2 subunits. Concentrically layered shells of density, with no regular contributions from higher-resolution terms, occupy a substantial part of this volume (Fig. 9A). As in the electron-density maps from crystals of reovirus and BTV cores 2; 3; 14, these shells arise from the close packing of tightly coiled RNA. They do not extend under the five-fold positions; instead, there is a well defined, roughly cylindrical feature projecting inward around each fivefold axis, with rod-like substructures, some of which can clearly be interpreted as α-helices. We call this structure a “fivefold hub”. We attribute it to the N-terminal segments of the ten abutting VP2 subunits, in agreement with cryo-EM analysis of recombinant VLPs containing N-terminally deleted VP2 15. We can assign at least one set of α-helices in the fivefold hub to residues 18 to 30, based on the pattern of identifiable side-chain density. Moreover, the entire hub is so situated that its outer rim extends to the positions occupied by residue 81 of the five VP2A subunits and the likely position of the corresponding residues of the five VP2B subunits (Fig. 9B). The overall volume occupied by the hub is ~2.5×105 Å3, roughly as expected for a compactly folded, hydrated structure composed of about 800 amino-acid residues (i.e., residues 1-80 of ten VP2 molecules). The same structure can be seen in the density map derived by single-particle reconstruction from cryo-EM images of rotavirus DLPs 5.

Fig 9.

Internal features of the electron density map and their interpretation. A. Contoured map in the vicinity of a fivefold axis, showing layers of density (magenta) attributed to coiled RNA. Scale shows radius (distance from center) in Å. B. The fivefold hub. Density from a 2Fo-Fc map, filtered to 7 Å resolution and contoured at 0.9σ, in the region around the fivefold axis boxed in A. C. Schematic diagram of the interior structures. The relative spatial relationship of these features is shown with suggested connections (dotted lines) indicating that the N-terminal extension of VP2 may form an internal channel.

Discussion

We summarize our overall conclusions as follows. The VP6 trimer in the DLP has essentially the same conformation that it has in isolation9. The bulk of the VP2 polypeptide chain (residues 81-880) folds into a plate-like structure resembling those of the corresponding shell proteins, known as VP3 and λ1, in orbiviruses and orthoreoviruses, respectively. The two conformers of VP2, designated VP2A and VP2B, within the icosahedral asymmetric unit are somewhat bent with respect to each other, but otherwise very similar. The N-terminal residues (1-80) of VP2 form a previously undetected, inward projecting “fivefold hub”, condensed around five radially directed α-helices. Although we can assign sequence within the hub only to these helices, it is clear that each hub contains five VP2A and five VP2B N-terminal arms, which are known to be essential for recruiting VP1 and VP3 into an assembling particle. Lower resolution RNA density is evident in three or four concentric layers in the regions between the fivefold hubs. We propose that the hubs function not only to organize the assembly unit of the inner shell but also as spools around which genomic dsRNA segments can coil and as guides for extrusion of nascent mRNA.

Interpreting RNA density

When double stranded nucleic acids are condensed, either by ATP-driven packaging within a phage head or by polymer-induced compaction, the most stable configuration is a more or less regular coil, with local close packing of adjacent segments 16; 17. An everyday analogy for the packing of a stiff but bendable rod within a confined region is the winding of a garden hose in a hose pot. The energetics of nucleic-acid condensation are dominated by electrostatic repulsion and resistance to bending. Both will cause the outermost coils to pack tightly against the confining structure – in this case, the VP2 shell -- and successive layers will pack against the first. The mean spacing between adjacent segments of RNA double helix will be determined by the balance of electrostatic repulsion, which will space adjacent segments as far from each other as possible, and stiffness, which will cause the RNA to avoid tight curvature (e.g., immediately adjacent to the spool). In dsDNA-containing phage heads, the former dominates, and in under-filled heads the DNA coils expand to fill the available internal volume 17. In the absence of any specific grooves or strongly varying patches of charge on the inward-facing surface of VP2, the outer layer of RNA double helices in rotavirus can be expected to create a uniform shell, except where the fivefold hub (and associated VP1 and VP3) intervenes.

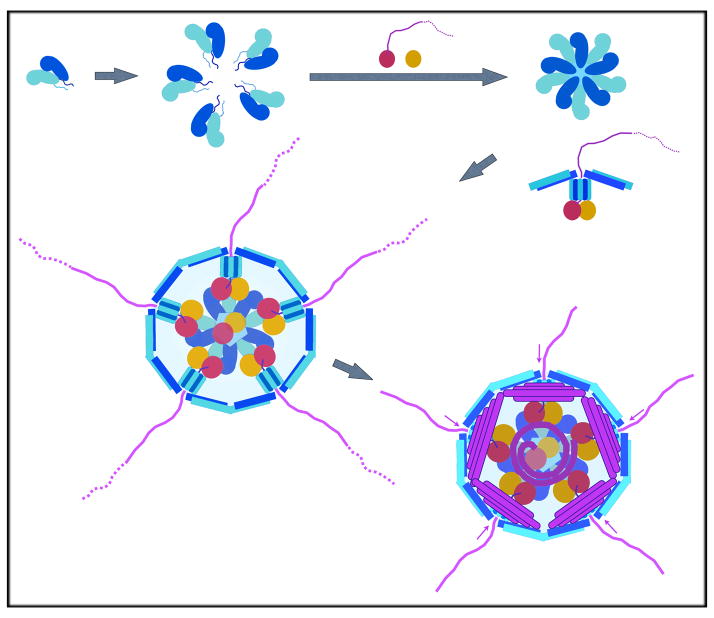

The eleven dsRNA segments within a rotavirus particle must coil independently, because transcription of each appears to proceed independently and there are multiple rounds. Transcription is conservative: mRNA for each segment is copied by an associated VP1 from the minus-sense template strand. The crowding of the viral interior provides insufficient space for diffusion of VP1 and therefore requires that each genomic segment spool through its polymerase, with a propagating transcription “bubble” allowing the template strand to pass through the protein. The nascent transcript exits at the fivefold axis 18, possibly guided by the fivefold hub, with which the polymerase probably remains at least loosely associated (see below). VP1 must also generate the minus strand of each segment (and hence the genomic duplex segment) within a newly assembled particle, and the replication mechanism may help organize the independent coils. VP1 has a site to bind the 5′ 7-MeG cap on the plus-sense strand; this attachment may keep each polymerase molecule associated with its “own” genomic segment 19. Fig. 11 illustrates the picture most consistent with these constraints and with the density layers shown in Fig. 9A. A related picture has been adduced for orbiviruses 14.

Fig. 11.

Model for DLP assembly, VP2 is in blue (dark and light for A and B conformers, as in Fig. 2); VP1, in red; VP3, in orange; RNA segments, in magenta. VP1 recruits (+)-RNA and VP3, and these components come together with five VP2 dimers to form the fundamental assembly unit. Twelve such units (one lacking RNA and potentially lacking VP1 and VP3) come together to form a DLP; synthesis of (−)-RNA inside the particle reels in the (+)-strand. The mechanism by which one of each RNA segment is incorporated remains unspecified.

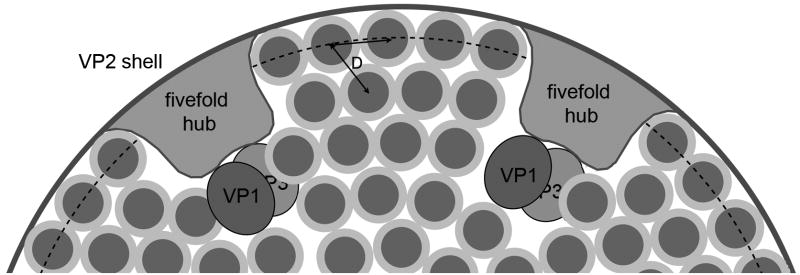

At low resolution, a dsRNA segment can be approximated as a grooved cylinder with a 20 Å van der Waals diameter. Local hexagonal packing of RNA segments, with packing diameter D (>20 Å, due to electrostatic repulsion and hydration), will give rise to density maxima spaced equally inward at 0.87D (Fig. 10). The first such maximum will be at a distance from the inward facing surface of VP2 (which is roughly spherical, at the resolution set by D) determined by the van der Waals radius of an RNA cylinder and the thickness of the hydration layer between the protein and RNA. The inward-facing radius of the VP2 shell (estimating the mean van der Waals surface from the atomic model) is 240 ± 5 Å. The radii of the three clearly defined RNA layers (Fig 9) are 225, 196, and 167 Å. From these numbers, we can estimate D= 33 Å. The volume within the cavity defined by the inner surface of VP2 (5.8×107 Å3) must contain 11–12 copies each of VP1 and VP3, the 12 fivefold hubs (residues 1-80 from 120 copies of VP2), and the RNA. Assuming a partial specific volume of 0.72 cm3/g for protein and an average hydration (water-accessible surface grooves, etc.) of 0.35 g/g, the RNA can then fill a total of 4.8×107 Å3. A center-to-center distance of D= 33 Å in a locally hexagonal array, and a linear density of 1 bp per 2.8 Å (A-form RNA), implies a volume of 2.6×103 Å3/bp and hence a total RNA content of ~18.5 kbp, in excellent agreement with the total number of base pairs in the rotavirus genome.

Fig. 10.

Schematic cross-section of rotavirus interior, illustrating dsRNA packing. The diagram is approximately to scale (for an internal radius of ~240 Å for the VP2 shell and for D, the packing diameter of the dsRNA segments, ~ 33Å). The dsRNA should be pictured as coiled around each fivefold hub, with approximate hexagonal close packing in cross section. The principal density of the RNA helices is about 20 Å in diameter; the lighter region around each cross-section shows the hydration layer.

We emphasize that the relatively well-ordered organization of the genomic RNA does not depend on any specific interactions with VP2. It is simply the result of tight packing and of mechanisms for packaging, minus-strand synthesis, and multiple rounds of transcription that avoid entanglement. Indeed, any specific or preferential interactions with particular surfaces of VP2 would probably hinder polymerase activity, by creating local “sticking points” for the dsRNA segments passing across them.

The fivefold hub

Clear definition of density for the fivefold hub, not detected in previous structural analyses of dsRNA virus particles, accounts for the N-termini of all VP2 subunits. We suggest that the hub has three distinct but related functions in rotavirus assembly, replication, and transcription. The first is to organize the assembly unit of the inner shell, by recruiting a copy of VP1 or of a VP1-VP3 complex, perhaps together with a segment of plus-strand RNA. The second is to serve as a shaft around which coils the dsRNA segment generated from the packaged plus-strand by in situ minus-strand synthesis. The third is to guide nascent mRNA out through its exit channel (and perhaps to guide (+)-strand RNA as it is pulled into the assembling core through minus strand synthesis (see Fig. 11).

A VP2 decamer, organized by the fivefold hub and associated with a VP1/VP3 complex, is a likely assembly unit for the virion inner layer (Fig. 11). Although the fivefold hub is not required to form a VP2 shell -- VP2 assembles into “single-layer particles” (SLPs) of the correct size and shape, even when it lacks the first N residues -- it is essential for recruiting co-expressed VP1 or VP3 20. The proportion of incorporated VP1 is approximately one molecule per decamer. A similar ratio of VP1:VP2 is also optimal for polymerase activation. VP1 recognizes a conserved sequence at the 3′ end of each viral plus-strand RNA segment, but initiation of minus-strand synthesis requires VP2 (with intact N-terminus), in a roughly 10:1 ratio 19; 21. The fivefold hub thus appears to link the VP1:RNA complex (presumably with an associated VP3) and the shell-forming domains of VP2. The molecular characteristics of this linkage remain to be detemined, but only when the linkage has been established will VP1 commence replication. Some association between VP1 and VP2 presumably persists even during transcription, as the polymerase must direct its transcripts into the exit pore in the VP2 shell. The fivefold hub has a channel along its axis, and a polymerase tethered near the tip of this channel could readily extrude transcripts along it.

The layers of RNA density surround the fivefold hubs. If the dsRNA is wound into independent coils, then the hubs are likely to be spools around which the RNA winds. It is possible that the way in which dsRNA emerges from the polymerase helps generate these coils 19.

RNA packaging and dsRNA synthesis

The properties of replication intermediates isolated from infected cells indicate that assembly of VP1 and VP2 into SLPs (and even into DLPs) precedes (−)-strand synthesis and that the (+)-strand template recruited by VP1 moves into the particle as synthesis proceeds 22. Fig. 11 is a diagram of the RNA packaging process suggested by these observations and by the ICP structure. In this model, progressive (−)-strand synthesis and formation of a double-strand product reels the (+)-strand into the particle (SLP or DLP) and spools each segment of the genomic dsRNA around its fivefold hub. Certain aspects of Fig. 11 have formal similarities to other nucleic-acid packaging processes. For example, in P22 and some other bacteriophage heads, there appears to be a protein shaft around which the DNA can coil as it enters 23, driven in that case by an ATP-dependent pump at the portal (rather than by the activity of an internal polymerase).

Various features of the mechanism embodied in Fig. 11 may not apply to other dsRNA viruses. For example, in dsRNA phage, such as φ6, the (+)-RNA templates are fully packaged before dsRNA synthesis starts 24. The orthoreovirus polymerase, λ3, does not seem to require the core shell protein, λ1, to initiate polymerization, nor have structural studies suggested recognition of 3′ sequences by the λ3 template channel 25, but it is possible that slightly different local mechanisms lead to the same larger-scale processes.

A remaining puzzle posed by dsRNA virus assembly is the mechanism that selects for packaging one copy each of the various gene segments. If a picture such as the one embodied in Fig. 11 is correct, some sort of sequence- and structure-specific interaction among the (+)-strand segments is likely to determine selectivity; viral non-structural proteins (e.g., NSP2: 26; 27) might also contribute. The interactions and structures determining RNA selection might occur only outside the synthetically active particle, and they would then dissolve during completion of dsRNA synthesis and RNA packaging.

Materials and Methods

Purification and crystallization

Rotavirus (UK Bovine isolate) DLPs were prepared in the laboratory of A.R. Bellamy (University of Auckland), according to the procedure described in 28. In brief, virus was propagated in MA104 cells, grown in 1585 cm2 roller bottles. Cells were harvested after 70 hrs and the DLPs purified from the lysate of a concentrated cell pellet. We obtain identical crystals from DLPs prepared in this way (i.e., particles isolated before they have budded into the ER and matured into virions) and from DLPs prepared by uncoating purified virions. The particles were transported in CsCl2 as recovered from the final CsCl2 gradient. Following dialysis against 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% sodium azide, the particles were centrifuged at 41,000 rpm in a Beckman SW41 swinging bucket rotor for 2 hours, and the pellet was re-suspended in the dialysis buffer to a concentration of 25 mg/mL and used directly for crystallization.

The DLP crystallized using the hanging drop method with drops containing 1 μL protein and 1 μL well solution at 22 °C. The optimized well solution contained 50 mM NaCl, 375 mM Na2SO4, 1.6% poly(ethylene glycol) 10,000 (PEG 10K), 0.02% sodium azide, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5. Crystals appeared within 3 weeks and grew to maximum size (0.5 mm × 0.5 mm × 0.4 mm) in ~6 months. Initial x-ray analysis determined that the crystals were of space group P212121 with the following unit cell dimensions: a = 740.75, b = 1198.07, and c = 1345.41. There were four rotavirus DLPs per unit cell with each crystallographic asymmetric unit containing an entire particle.

Data collection and processing

Crystals were gently transferred to a stabilization solution containing well solution with 8.5% β-D-octoglucopyranoside, to reduce surface tension. Crystals were mounted in quartz capillaries and stored until needed. Diffraction data at Bragg spacings between 215 Å and 3.8 Å were collected at CHESS beamline F1 using a dual plate Quantum 4 CCD detector at a distance of 750 mm with 0.1° oscillations at a single wavelength. The beam was collimated to 100 μm, and crossfire was further reduced using the hutch entrance slits, which were about 2 m upstream of the defining collimator. Each crystal was exposed (40 s) once for every crystal volume as defined by the beam size. Only data from crystals with mosaicity < 0.055° (over 2.3 million reflections) were used for the final structure determination. Reflections were indexed and integrated with a modified version of Denzo 29 and scaled using SCALA and POSTREF 30. Statistics are shown in Table 1. The data were 20.8% complete overall with 8.2% completeness in the final 4.0-3.8 Å shell. Sixty fold redundancy implies that there is some phase extension power, even at the limiting resolution.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Data collection statistics | |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 223-3.8 |

| Space Group | P212121 |

| Unique reflections | 2,393,850 |

| Redundancya | 1.1 (1.0) |

| Completenessa (%) | 20.8 (8.2) |

| I/σa | 3.4 (1.0) |

| Rsyma,b (%) | 18.2 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Reflections used in refinement | 1,823,596 |

| Polypeptide chains | 900 |

| Protein atoms | 3,233,140 |

| Residues in allowed regions of Ramachandran plot VP2 (%) | 97.2 |

| Residues in most favored regions of Ramachandran plot VP2 (%) | 60.6 |

| Residues in allowed regions of Ramachandran plot VP6 (%) | 99.7 |

| Residues in most favored regions of Ramachandran plot VP6 (%) | 78.1 |

| RMSD bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 |

| RMSD bond angles (deg) | 1.67 |

| Mean B value (Å2) | 164.0 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30–3.8 |

| R-factora,c | 32.8 (55.9) |

| Free R-factora,c | 33.9 (57.9) |

Values for last shell given in parentheses.

Rsym=Σ(I− I)/I. I is the average intensity over symmetry equivalent reflections.

R-factor=(Σ Fobs − Fcalc)/Σ Fobs, where the summation is over the working set of reflections. For the free R-factor, the summation is over the test set of reflections (2% of the measured reflections selected in thin shells).

Initial Map calculation

Starting phases at 18.2 Å were obtained from a cryoEM reconstruction of the DLP at ~20 Å (kindly provided by BVV Prasad, Baylor College of Medicine). The map was modified to as described in 2, so that it had a uniform positive density within a defined contour level and zero outside. The initial orientation of the EM reconstruction within the unit cell was determined from an icosahedral locked self rotation function 31 and translation function (AMORE: 32) using structure factors from the modified map. During the course of phase extension, orientation parameters were optimized by monitoring improvements to Fo/Fc correlations when applying small shifts to the particle rotation/translation.

Phase extension

Phase extension proceeded in steps of one reciprocal lattice point, using RAVE and associated programs essentially as described in 2. Fcalc from the averaged map was used for missing Fobs. At each cycle, the density map was averaged in a P1 cell that covered a single DLP, and the averaged density was then interpolated back into the crystallographic unit cell for phase generation to begin the next cycle. The initial averaging mask was generated using the outer surface of the starting 18.2 Å model with an inner radius of ~200 Å. The mask was periodically recalculated at higher resolution on a finer grid as required using CCP4 (EXTEND) 30 and RAVE (MAPMAN, MAMA) routines 33.

Model Building and Refinement

The final w(2Fo-Fc) (where w is fig of merit) map from the phase extension procedure was sharpened with a B-factor of −150. It showed clear density for the thirteen (per icosahedral asymmetric unit) VP6 subunits and the two VP2 monomers per icosahedral asymmetric unit, for which no structure had previously been determined. There was connected density for the VP2 main chain and reasonable density for many side chains, and the VP2 polypeptide chain could be built without great difficulty into the density with the program O 34. Parts of the VP6 monomers, especially those at the VP6-VP2 interface, were also rebuilt with reference to the density. The model was refined using a version of CNS 35 specifically compiled to take advantage of the additional memory available on a 64-bit Opteron processor. Positional refinement, restrained group B-factor refinement, and difference map generation in CNS proceeded using 60-fold NCS constraints within the icosahedral asymmetric unit and additional sets of NCS restraints among the 13 VP6 monomers and the two VP2 monomers. Lower-resolution 2mFo-DFc maps were also calculated to visualize the interior densities corresponding to both the RNA layers and the features about the 5-fold.

The final refined model includes residues 81-880 of VP2 and 1 to 397 of VP6 with an R-work and R-free of 34.1 and 34.9, respectively (Table 1). The high non-crystallographic symmetry diminishes the cross-validation power of R-free; we suggest that lack of divergence from the working R is nonetheless a meaningful indication that we have avoided overrefinement in the outermost shells, where data completeness corresponds to much lower effective redundancy (see above). Overall, 91.1% of the residues in VP2 fall in the most favored and additionally allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot; the generously allowed region contains 6.1%, and the disallowed region, the remaining 2.7%. The r.m.s. deviation from ideal bond lengths is 0.010 Å and from ideal angles is 1.7°.

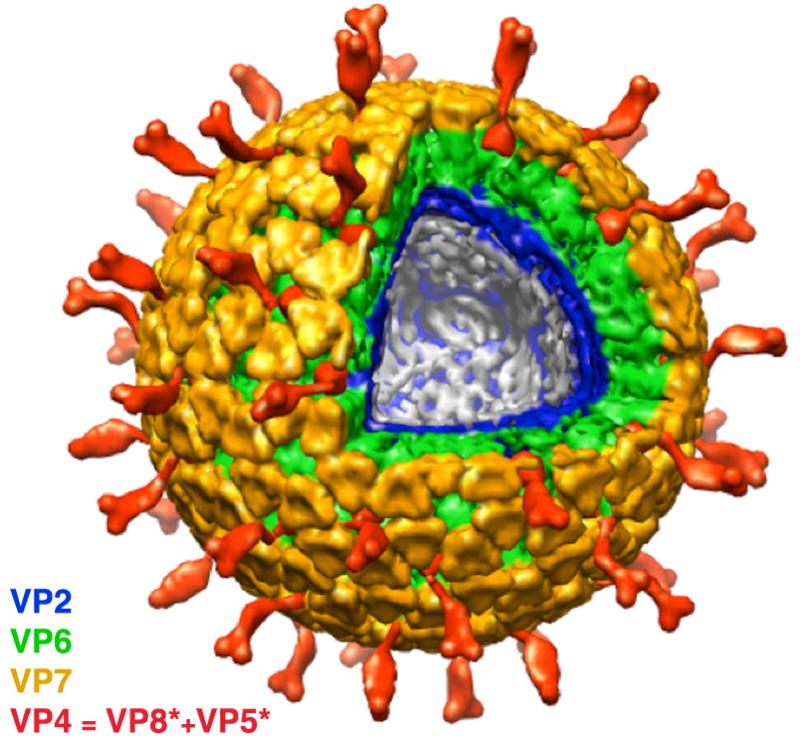

Fig 1.

Cut-away view of the complete rotavirus virion (TLP), based on cryoEM reconstructions and assignments of densities. The two outer-layer proteins are in yellow (VP7) and red (VP5*/VP8*). The middle-layer protein (VP6) is in green; the inner-layer VP2, in blue. Coils of dsRNA (not shown here) fill the interior, organized in part by internal structures of the ICP described in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Anthony and S. Greig for assistance in virus propagation and purification, Barbara Harris for advice and assistance with crystallization, and staff of CHESS and MacCHESS for cheerful support. The research was supported by NIH grant CA13202 (to SCH) and by Project Grants from the Health Research Council of New Zealand (to ARB). SCH is an Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Accession numbers

Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 3KZ4.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schiff LA, Nibert ML, Tyler KL. Orthoreoviruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology, fifth edition. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1853–1915. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinisch KM, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 A resolution. Nature. 2000;404:960–7. doi: 10.1038/35010041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimes JM, Burroughs JN, Gouet P, Diprose JM, Malby R, Zientara S, Mertens PP, Stuart DI. The atomic structure of the bluetongue virus core. Nature. 1998;395:470–8. doi: 10.1038/26694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tihova M, Dryden KA, Bellamy AR, Greenberg HB, Yeager M. Localization of membrane permeabilization and receptor binding sites on the VP4 hemagglutinin of rotavirus: implications for cell entry. J Mol Biol. 2001;314:985–92. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Settembre E, Xu C, Dormitzer PR, Bellamy R, Harrison SC, Grigorieff N. Near-atomic resolution using electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle reconstruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1867–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711623105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu X, Jin L, Zhou ZH. 3.88 A structure of cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 2008;453:415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Baker ML, Jiang W, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Rotavirus architecture at subnanometer resolution. J Virol. 2009;83:1754–66. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01855-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulibaly F, Chevalier C, Gutsche I, Pous J, Navaza J, Bressanelli S, Delmas B, Rey FA. The birnavirus crystal structure reveals structural relationships among icosahedral viruses. Cell. 2005;120:761–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mathieu M, Petitpas I, Navaza J, Lepault J, Kohli E, Pothier P, Prasad BV, Cohen J, Rey FA. Atomic structure of the major capsid protein of rotavirus: implications for the architecture of the virion. EMBO J. 2001;20:1485–97. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heiman EM, McDonald SM, Barro M, Taraporewala ZF, Bar-Magen T, Patton JT. Group A human rotavirus genomics: evidence that gene constellations are influenced by viral protein interactions. J Virol. 2008;82:11106–16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01402-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charpilienne A, Lepault J, Rey FA, Cohen J. Identification of rotavirus VP6 residues located at the interface with VP2 that are essential for capsid assembly and transcriptase activity. J Virol. 2002;76:7822–7831. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7822-7831.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greig SL, Berriman JA, O’Brien JA, Taylor JA, Bellamy AR, Yeager MJ, Mitra AK. Structural determinants of rotavirus subgroup specificity mapped by cryo-electron microscopy. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:209–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepault J, Petitpas I, Erk I, Navaza J, Bigot D, Dona M, Vachette P, Cohen J, Rey FA. Structural polymorphism of the major capsid protein of rotavirus. EMBO J. 2001;20:1498–507. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouet P, Diprose JM, Grimes JM, Malby R, Burroughs JN, Zientara S, Stuart DI, Mertens PP. The highly ordered double-stranded RNA genome of bluetongue virus revealed by crystallography. Cell. 1999;97:481–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80758-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawton JA, Zeng CQ, Mukherjee SK, Cohen J, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Three-dimensional structural analysis of recombinant rotavirus-like particles with intact and amino-terminal-deleted VP2: implications for the architecture of the VP2 capsid layer. J Virol. 1997;71:7353–60. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7353-7360.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maniatis T, Venable JH, Jr, Lerman LS. The structure of psi DNA. J Mol Biol. 1974;84:37–64. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Earnshaw WC, Harrison SC. DNA arrangement in isometric phage heads. Nature. 1977;268:598–602. doi: 10.1038/268598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawton JA, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Three-dimensional visualization of mRNA release from actively transcribing rotavirus particles. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:118–21. doi: 10.1038/nsb0297-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, McDonald SM, Tortorici MA, Tao YJ, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Nibert ML, Patton JT, Harrison SC. Mechanism for coordinated RNA packaging and genome replication by rotavirus polymerase VP1. Structure. 2008;16:1678–88. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng CQ, Estes MK, Charpilienne A, Cohen J. The N terminus of rotavirus VP2 is necessary for encapsidation of VP1 and VP3. J Virol. 1998;72:201–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.201-208.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallegos CO, Patton JT. Characterization of rotavirus replication intermediates: a model for the assembly of single-shelled particles. Virology. 1989;172:616–27. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton JT, Gallegos CO. Rotavirus RNA replication: single-stranded RNA extends from the replicase particle. The Journal of general virology. 1990;71 ( Pt 5):1087–94. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-5-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JE, Chiu W. DNA packaging and delivery machines in tailed bacteriophages. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:237–43. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qiao X, Qiao J, Mindich L. Stoichiometric packaging of the three genomic segments of double-stranded RNA bacteriophage phi6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4074–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tao Y, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. RNA synthesis in a cage--structural studies of reovirus polymerase lambda3. Cell. 2002;111:733–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayaram H, Taraporewala Z, Patton JT, Prasad BV. Rotavirus protein involved in genome replication and packaging exhibits a HIT-like fold. Nature. 2002;417:311–5. doi: 10.1038/417311a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang X, Jayaram H, Kumar M, Ludtke SJ, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Cryoelectron microscopy structures of rotavirus NSP2-NSP5 and NSP2-RNA complexes: implications for genome replication. J Virol. 2006;80:10829–35. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01347-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Street JE, Croxson MC, Chadderton WF, Bellamy AR. Sequence diversity of human rotavirus strains investigated by northern blot hybridization analysis. J Virol. 1982;43:369–78. doi: 10.1128/jvi.43.2.369-378.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collaborative Computational Project. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong L, Rossmann MG. Rotation function calculations with GLRF program. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:594–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navaza J. Implementation of molecular replacement in AMoRe. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:1367–72. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones TA. CCP4 Proceedings. SERC Daresbury Laboratory; Warrington, UK: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cown SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]