Abstract

Despite improved understanding of the pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), it remains a severe and progressive disease, usually culminating in right heart failure, significant morbidity and early mortality. Over the last decade, some major advances have led to substantial improvements in the management of PAH. Much of this progress was pioneered by work in animal models. Although none of the current animal models of pulmonary hypertension (PH) completely recapitulate the human disease, they do provide insight into the cellular pathways contributing to its development and progression. There is hope that future work in model organisms will help to define its underlying cause(s), identify risk factors and lead to better treatment of the currently irreversible damage that results in the lungs of afflicted patients. However, the difficulty in defining the etiology of idiopathic PAH (IPAH, previously known as primary pulmonary hypertension) makes this subset of the disease particularly difficult to model. Although there are some valuable existing models that are relevant for IPAH research, the area would value from the development of new models that more closely mimic the clinical pathophysiology of IPAH.

IPAH: a clinical overview

Clinical presentation and pathology of IPAH

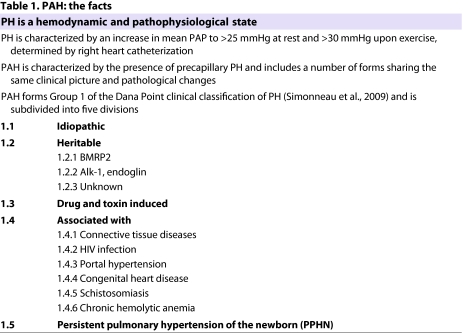

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) includes a heterogeneous group of conditions including idiopathic forms of the disease, known as idiopathic PAH (IPAH) (Simonneau et al., 2009). Despite the diversity of conditions in this group, it is defined by similarities in pathophysiological, histological and prognostic features, which are summarized in Table 1. Clinical manifestations of the disease are fairly consistent among PAH patients, regardless of its etiology (see case study). Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a hallmark of PAH, but PH includes all cases of increased pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), regardless of its cause. Patients with PH are initially diagnosed with sustained elevated PAP, such as a mean PAP of over 25 mmHg at rest or one that exceeds 30 mmHg with exercise, which is measured by right heart catheterization (Galie et al., 2009). PAH is also associated with a particularly severe arteriopathy, including increased thickness of the intima, media and adventitia of peripheral arteries, and muscularization of the precapillary arterioles and capillaries. This pathology often contributes to vascular lesions (e.g. plexiform lesion and neointimal proliferation), which obstruct the pulmonary arteries and arterioles. The plexiform lesion, although confined to approximately 15% of PAH patients, is a pathological hallmark of IPAH, since it infrequently occurs in other types of disease. Plexiform lesions arise from the monoclonal proliferation of endothelial cells; migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells; and the accumulation of circulating inflammatory and progenitor cells (Runo and Loyd, 2003; Tuder et al., 1994). This vascular pathology may lead to narrowing and/or occluding pulmonary arteries and arterioles in PAH patients.

Table 1.

PAH: the facts

Case study.

M.P. is a 34-year-old woman who, 14 months ago, presented with progressive dyspnea on exertion. She was initially diagnosed with asthma and prescribed an albuterol inhaler, but her dyspnea on exertion progressed, and seven months after her initial presentation she developed syncope after rapidly climbing a flight of stairs. At that time, the examination was notable for elevated jugular venous pressure, clear lungs and a tricuspid regurgitation murmur. Trace pedal edema was also noted. An echocardiogram was obtained and revealed an elevated pulmonary arterial systolic pressure of 67 mmHg, as well as right ventricular hypertrophy. An extensive evaluation of the patient’s PH was negative, and included a cardiac catheterization documenting PAP of 72/44 mmHg and a cardiac index of 2.4 l/min/m2. Given the negative evaluation for associated conditions, the patient was diagnosed with IPAH. She was treated with inhaled iloprost, oxygen, warfarin and diuretics for seven months. Although her functional capacity remains limited by dyspnea on exertion, her overall functional status and symptoms improved and her six-minute walk distance increased by 37 meters to 234 meters. A repeat cardiac catheterization after six months of therapy showed a mild decrease in PAP to 64/39 mmHg, and an increase in cardiac index to 2.6 l/min/m2.

Pathobiology of IPAH

In PAH, blood flow through the pulmonary blood vessels becomes restricted. The right side of the heart must compensate to force blood through the small arteries and arterioles of the lungs. If left untreated, PAH has a very poor prognosis. There is currently no method to identify individuals who are at risk for developing the disease. No single mechanism can completely account for the etiology of PAH. Increased pulmonary vascular resistance may develop from vasoconstriction, vascular remodeling or in situ thrombosis.

At least some of the sustained vasoconstriction and concentric arterial remodeling is thought to come from the decreased expression and function of potassium ion (K+) channels, especially voltage-gated K+ channels, in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs). Decreased K+ channel activity causes membrane depolarization that subsequently increases the cytosolic calcium ion (Ca2+) concentration ([Ca2+]cyt) in PASMCs by opening voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, causing vasoconstriction. The resulting increase in [Ca2+]cyt stimulates PASMC migration and proliferation, which leads to medial hypertrophy and concentric vascular remodeling. The reduced activity of K+ channels also slows down apoptotic volume decrease and inhibits the apoptosis of PASMCs, which further contributes to pulmonary vascular medial hypertrophy (Pozeg et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 1998). Thus, K+ channel dysfunction is thought to significantly contribute to the pathology of PAH.

The endothelium also has a role in the disease process. It is not clear whether dysfunction, or injury of the endothelium, predisposes individuals to disease or whether it results from the increased PAP that is associated with disease. In either case, endothelial damage reduces the production of anti-proliferative and vasodilator substances such as prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Increased release of pro-proliferative and vasoconstrictive agents such as thromboxane A2 and endothelin-1 further elevates vascular tone (Christman et al., 1992; Giaid, 1998). Smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts all proliferate excessively in PAH, contributing to occlusion of vessel lumens and detrimental vasculopathy (Masri et al., 2007; Stenmark et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2008). Several inheritable or acquired mutations or polymorphisms of genes that regulate the proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation of pulmonary vascular cells predispose individuals to IPAH. Some of these genes include those that encode the transforming growth factor β(TGF-β) receptor BMPR2, the serotonin transporter and transient receptor potential canonical 6 (TRPC6) (Hamidi et al., 2008; Machado et al., 2006; Rabinovitch, 2001; Yu et al., 2009).

Existing models for PH

Chronic hypoxic model of PH

Hypoxia-induced PH is consistent and reproducible in rats, despite some variability with age and between species. A chronically hypoxic (CH) model demonstrates pulmonary vasoconstriction, medial hypertrophy and increased muscularization of the small arteries with elevated smooth muscle α-actin. Remodeling of the precapillary arterioles results from increased medial thickening, and from smooth muscle cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy that occurs soon after disease onset. Maintaining CH rats at an altitude, to induce hypobaric conditions, elevates their PAP, decreases their numbers of aveoli and increases their PASMC endothelin production. These animals remodel their pulmonary vasculature. These characteristics mimic the symptoms found in humans, but CH rats develop concomitant systemic hypertension, which is absent in human PAH, suggesting that there are some important differences in their underlying physiology.

Non-rat CH models are used sometimes. Mice develop CH-induced PH, but their disease is substantially different from that seen in humans. It is associated with minimal vascular remodeling, whereas in humans pulmonary vascular remodeling, which is characterized by intimal and medial thickening, is the major known cause for elevated pulmonary vascular resistance. Another inconsistency of the mouse model is that its adventitial thickening and fibrosis occurs in the proximal pulmonary arteries, whereas in humans it often occurs in distal pulmonary arteries. Neonatal calves develop severe PH with significantly elevated PAP when exposed to reduced oxygen (12.5% O2), which is associated with substantial vascular remodeling. Their medial and adventitial thickening is extensive, and mesenchymal progenitor cells and mononuclear cells accumulate in the arterial wall (Das et al., 2001; Davies et al., 1991), similar to in humans. The general use of these models is, however, fairly limited.

CH-induced PH in animal models is reversed when the animals are exposed to normal oxygen concentrations, making it fundamentally different from IPAH in humans, which occurs in normoxic conditions and causes irreversible intimal fibrosis and plexiogenic lesions. A modification of the CH model involves administration of Sugen 5416, a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibitor, to CH rats (Taraseviciene-Stewart et al., 2001). This model emulates the hyperproliferative endothelial cell etiology and irreversible PH. Under these conditions, several animals develop persistent PH and right heart failure leading to deaths that look more similar to the disease progression in humans. Likewise, rats with an endothelin receptor B (ETB) deficiency develop a more severe form of PH. These rats may offer a more relevant model and can perhaps offer some insight into the unique mechanisms that contribute to PH in animals compared with IPAH in humans.

Monocrotaline-induced pulmonary vascular disease

The pneumotoxin monocrotaline (MCT) can be used to generate another animal model of PH. A single subcutaneous injection of MCT undergoes oxidation in the liver to form monocrotaline pyrrole. By an unknown mechanism, MCT rapidly induces severe pulmonary vascular disease that, over a period of one to two weeks, is followed by pulmonary vascular remodeling and elevated PAP. An infiltration of mononuclear inflammatory cells into the adventitia often precedes the medial hypertrophy. Reminiscent of PAH in humans, MCT-treated rats develop right ventricular hypertrophy with the right ventricular systolic pressure reaching up to 80 mmHg (Hessel et al., 2006).

MCT-induced PH varies among strains and species of animals. The favored model is the rat, which has a more consistent and predictable response than the mouse. Larger mammals, such as dogs, also respond to MCT and undergo vascular remodeling and neointimal formation (Gust and Schuster, 2001), but there is disparity in the susceptibility of individual animals, which is thought to be the result of differences in the pharmacokinetics and hepatic metabolism of MCT. However, there is also a suggestion that differences between Sprague-Dawley and Fisher 344 rats reflect a unique pulmonary vascular response (Pan et al., 1993).

The MCT model is not perfect for human PAH for other reasons as well. It is relatively easy to cure MCT-induced PH, and over 30 agents have shown therapeutic benefits that prevent or reverse MCT-induced PH. One of these molecules is the anorexigen dexfenfluramine that, paradoxically, is associated with the development of IPAH in humans. These confusing data are summarized in a recent review (Stenmark et al., 2009). In the MCT model, single-sided pneumonectomy is required to produce neointimal formation and obliteration of the smaller arteriole lumens that are experienced commonly by human patients (White et al., 2007). The comparative pathologies between MCT mice with pneumonectomy and the standard MCT model are shown in Fig. 1. This modified model is now frequently utilized for etiologic studies.

Fig. 1.

Following pneumonectomy, neointima and smooth muscle hypertrophy are observed after MCT treatment. The panels show rat lung tissues stained with trichrome elastin. Lung tissues from rats treated with vehicle (left), MCT following pneumonectomy (centre) and MCT following a sham operation (right) are shown at low magnification. Bar, 250 μm (upper panels). The lower panels are higher magnification views (×40) of the vessels that are indicated by arrows in the upper panels. Note the extensive neointimal formation in the MCT following pneumonectomy panel only; smooth muscle hypertrophy is observed in both of the MCT-treated rats. Figure used with permission from The American Physiological Society (White et al., 2007).

It is interesting to note that inactivation of bone morphogenetic protein receptor (BMPR) signaling in both the MCT and CH models of PH may be crucial for pathogenesis (Long et al., 2009). This supports the human studies implicating BMPR type II (BMPR2) mutations as an underlying cause in over 70% of familial PAH cases and approximately 20% of IPAH cases. The expression of two related receptors, BMPR2 and BMPR1a, is reduced in patients with idiopathic PAH, suggesting that BMP–TGF-β signaling pathways are disrupted in PAH.

Genetically modified models of pulmonary hypertension

The association between PAH and BMPR2 gene mutations was first observed in 2000 (Lane et al., 2000), and heterologous mice (BMPR2+/–) were soon developed to determine the role of BMPR2 in PAH (Beppu et al., 2004; Song et al., 2008). However, these mice exhibit normal PAP at rest and require the presence of an additional factor, such as interleukin (IL)-1β or serotonin (Long et al., 2006; Song et al., 2005), to elevate their PAP. Homozygous knockout of BMPR2 (BMPR2−/−) is embryonically lethal, which suggests that a conditional knockout may prove valuable in the future. Still, only around 20% of patients harboring BMPR2 gene mutations exhibit PH, suggesting that additional genetic and/or environmental factors are necessary to develop PAH.

In a search to uncover the mechanisms of neointimal lesion formation in humans, researchers have generated a variety of models. Blocking the VEGF receptor in CH rats with Sugen 5416 causes severe PH associated with precapillary arterial lesions and plexiform lesions (Taraseviciene-Stewart et al., 2001). Another model uses overexpression of S100A4 (MTS1) to cause plexiogenic lesions in approximately 5% of transgenic mice (Greenway et al., 2004; Spiekerkoetter et al., 2008). Rodents lacking ETB are predisposed to CH-induced PH. These animals exhibit promising, exaggerated pulmonary vasopressor responses to both acute hypoxia and endothelin infusion, but they do not form neointimal lesions (Ivy et al., 2005). To recapitulate the increased expression of IL-6 that was identified in the serum and lungs of PAH patients (Steiner et al., 2009), Steiner and colleagues created transgenic mice with lung-specific overexpression of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Savale et al. characterized IL-6 knockout mice (Savale et al., 2009). Both studies showed a correlation between IL-6 expression and the development of vasculopathy, replicating the severe PAH in humans; however, further work is necessary to determine exactly how IL-6 contributes to vascular remodeling.

The initiation and progression of human PAH involves multiple cellular and molecular mechanisms. The aforementioned work indicates that it is important to stimulate the generation of models to examine other pathways that might influence PAH. It is hoped that some of these genetic technologies may produce more informative models of PAH.

Clinical terms.

- Albuterol

short-acting β2-adrenergic receptor agonist that increases airflow to the lungs by relaxing the muscles along the airway (bronchodilator)

- Dyspnea

shortness of breath, often indicating pathology related to the airways or lungs

- Iloprost

synthetic analog of the prostaglandin PGI2; used to dilate blood vessels

- Plexiform lesion

a pathological change that usually occurs at the branch point of arteries. They are associated closely with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and contribute to fibrotic occlusion of vessels

- Pulmonary hypertension (PH)

a general term for abnormally elevated pressure in the arteries of the lungs or pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), which creates added strain on the right side of the heart

- Sildenafil

an inhibitor of cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase type 5, an enzyme that regulates blood flow, which is also used to treat erectile dysfunction (trade names include Viagra and Revatio)

- Simvastatin

a type of statin (trade names include Zocor or Simvacor)

- Statins

a class of drug used to reduce plasma cholesterol in order to control hypercholesterolemia and to protect against heart disease

- Syncope

transient loss of consciousness or self-awareness

- Warfarin

(also known as coumadin) a very widely used anti-coagulant that requires routine monitoring to ensure therapeutic and safe levels are achieved

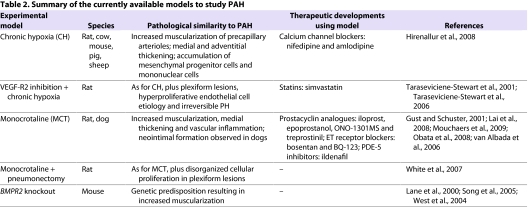

Moving research forward with new models

Current models have identified treatments for the acute symptoms of PAH; however, the etiology and underlying mechanisms of the disease remain unknown. This highlights the need to improve upon the current animal models of PH. An extensive, although not exhaustive, list of the current models of PH and the pathological characteristics of the disease that they represent are featured in Table 2. Identification of the unique disease characteristics in model organisms and human patients should offer some insight into the mechanisms that contribute to disease.

Table 2.

Summary of the currently available models to study PAH

What constitutes a good model of PAH?

An ideal model for PAH would recapitulate all aspects of the disease as it occurs in humans, including its pathological and hemodynamic alterations as well as its development and progression. The ‘ideal’ model of PAH should recapitulate the following pathological and hemodynamic features of patients with IPAH: (1) excessive pulmonary vascular remodeling characterized by intimal and medial hypertrophy, plexiform lesions and neointimal proliferation, obliteration and muscularization of small pulmonary arteries; (2) sustained pulmonary vasoconstriction; (3) in situ thrombosis in small arteries; (4) increased stiffness or decreased compliance of large and medium arteries; (5) significantly increased pulmonary vascular resistance and mean PAP; and (6) increased afterload in the right ventricle. This ideal model should also be free of unrelated toxic side effects.

Although no currently available model can fulfill all of these criteria, animal models have assisted enormously in understanding the pathophysiology of the disease. Notably, existing therapeutic strategies owe their discovery to observations made in animal models of the disease. Prostacyclin analogues (including iloprost, epoprostanol and treprostinil) were identified and tested in the MCT and CH rat model of PH.

Data from therapy studies in model organisms mostly agree with the clinical data showing that vasodilatation and exercise capacity improve with treatment (Lai et al., 2008; Lang et al., 2006; Obata et al., 2008). Prostanoids remain a mainstay for the treatment of PAH and are currently in clinical trial as part of a combinatorial therapy with treatments such as sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitor. The discovery of sildenafil as a therapeutic strategy for PAH was incidental, but it is effective in animal and cellular models of PH and demonstrates short-term benefits in humans (Wang et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2001). Combinations of sildenafil with the HMG-CoA (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A) reductase inhibitor, statins (e.g. simvastatin) (Satoh and Satoh, 2008; Zhao et al., 2009) or the endothelin-1 receptor antagonist bosentan (Mouchaers et al., 2009) have all been shown to have a greater therapeutic effect than sildenafil alone.

Statins are used most often to lower plasma cholesterol, but the beneficial ‘pleiotropic’ effects of statins extend to PAH. Evidence suggests that statins enhance endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) production and have anti-inflammatory effects in CH rats. Treated CH rats also experience a decrease in PAP by greater than 50% and a decrease in pulmonary arteriole muscularization (Girgis et al., 2003). Furthermore, the statin simvastatin reduces neointimal formation in a MCT-pneumonectomy rat model of PH, and reverses PH and vascular remodeling (Girgis et al., 2007; Nishimura et al., 2002; Nishimura et al., 2003). The positive effect of statins on PH is not ubiquitous, since another drug family member, atorvastatin, does not influence PH (McMurtry et al., 2007). Still, animal models indicate a potential patient benefit from treatment with statins.

Calcium channel blockers (CCBs), such as nifedipine and amlodipine, were used to treat some patients with PAH for many years (Stanbrook et al., 1984). Unfortunately, patient responses to CCBs are limited despite significant benefits being shown in hypoxic and MCT-treated animal models (Hirenallur et al., 2008). In patients that do respond, CCB therapy causes pulmonary vasodilatation (Zierer et al., 2009). The response of patients to short-acting pulmonary vasodilators such as iloprost, epoprostenol, nitric oxide or adenosine helps to identify the subset of PAH patients that might respond to CCB therapy (Jing et al., 2009). The studies that lead to these therapeutic advancements for PAH have been carried out in the ‘classic’ models of PH, such as rodents exposed to either CH or treated with MCT.

In creating an ideal model for IPAH, the challenge is to find answers to the following problems: (1) how to generate a model that recapitulates all of the pathological abnormalities in human patients; (2) to determine whether a model of pathogenesis will also be useful for large-scale pharmacological studies to identify novel therapeutic approaches; and (3) what types of organisms/animals (and species) can provide relevant models to understand IPAH. Since the pathogenic mechanisms of IPAH involve all pulmonary vascular cell types, various cell functions and multiple signaling pathways, a new strategy for generating an ideal model needs to aim at the multiple targets that are affected in the human disease, including a variety of cell types and genes. An animal model with multiple cellular and molecular abnormalities in various cell types would be more appropriate for pathogenic and therapeutic studies on the human disease.

Clinical and basic research opportunities.

To find biomarkers that predict the susceptibility of an individual to disease

To identify the mechanistic differences that underlie PH-like disease in current model organisms versus human PAH

To use genetic information collected from human patients to design models that can define the etiology of PAH

To develop and characterize models for the identification and screening of therapeutics to prevent disease onset or to reverse some of the lasting consequences of PAH

Although animal models will undoubtedly continue to improve, it is unlikely that any one model will be able to successfully recapitulate the disease in humans. Human studies will always be an essential and mandatory step to scrutinize the efficacy and safety of novel treatment strategies for PAH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health ( HL64945 and HL66012. Deposited in PMC for release after12 months.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Beppu H, Ichinose F, Kawai N, Jones RC, Yu PB, Zapol WM, Miyazono K, Li E, Bloch KD. (2004). BMPR-II heterozygous mice have mild pulmonary hypertension and an impaired pulmonary vascular remodeling response to prolonged hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 287, L1241–L1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman BW, McPherson CD, Newman JH, King GA, Bernard GR, Groves BM, Loyd JE. (1992). An imbalance between the excretion of thromboxane and prostacyclin metabolites in pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med. 327, 70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M, Bouchey DM, Moore MJ, Hopkins DC, Nemenoff RA, Stenmark KR. (2001). Hypoxia-induced proliferative response of vascular adventitial fibroblasts is dependent on G protein-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 276, 15631–15640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies NW, Standen NB, Stanfield PR. (1991). ATP-dependent potassium channels of muscle cells: their properties, regulation, and possible functions. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 23, 509–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, Torbicki A, Vachiery JL, Barbera JA, Beghetti M, Corris P, Gaine S, Gibbs JS, et al. (2009). Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J. 30, 2493–2537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid A. (1998). Nitric oxide and endothelin-1 in pulmonary hypertension. Chest 114, 208S–212S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis RE, Li D, Zhan X, Garcia JG, Tuder RM, Hassoun PM, Johns RA. (2003). Attenuation of chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension by simvastatin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 285, H938–H945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis RE, Mozammel S, Champion HC, Li D, Peng X, Shimoda L, Tuder RM, Johns RA, Hassoun PM. (2007). Regression of chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension by simvastatin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 292, L1105–L1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenway S, van Suylen RJ, Du Marchie Sarvaas G, Kwan E, Ambartsumian N, Lukanidin E, Rabinovitch M. (2004). S100A4/Mts1 produces murine pulmonary artery changes resembling plexogenic arteriopathy and is increased in human plexogenic arteriopathy. Am J Pathol. 164, 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust R, Schuster DP. (2001). Vascular remodeling in experimentally induced subacute canine pulmonary hypertension. Exp Lung Res. 27, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi SA, Prabhakar S, Said SI. (2008). Enhancement of pulmonary vascular remodelling and inflammatory genes with VIP gene deletion. Eur Respir J. 31, 135–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessel MH, Steendijk P, den Adel B, Schutte CI, van der Laarse A. (2006). Characterization of right ventricular function after monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in the intact rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 291, H2424–H2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirenallur SD, Haworth ST, Leming JT, Chang J, Hernandez G, Gordon JB, Rusch NJ. (2008). Upregulation of vascular calcium channels in neonatal piglets with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 295, L915–L924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy DD, McMurtry IF, Colvin K, Imamura M, Oka M, Lee D-S, Gebb S, Jones PL. (2005). Development of occlusive neointimal lesions in distal pulmonary arteries of endothelin B receptor-deficient rats: a new model of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 111, 2988–2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing ZC, Jiang X, Han ZY, Xu XQ, Wang Y, Wu Y, Lv H, Ma CR, Yang YJ, Pu JL. (2009). Iloprost for pulmonary vasodilator testing in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 33, 1354–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai YJ, Pullamsetti SS, Dony E, Weissmann N, Butrous G, Banat GA, Ghofrani HA, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Schermuly RT. (2008). Role of the prostanoid EP4 receptor in iloprost-mediated vasodilatation in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 178, 188–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA, III, Loyd JE, Nichols WC, Trembath RC, The IPPH Consortium (2000). Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-β receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. 26, 81–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Gomez-Sanchez M, Kneussl M, Naeije R, Escribano P, Skoro-Sajer N, Vachiery JL. (2006). Efficacy of long-term subcutaneous treprostinil sodium therapy in pulmonary hypertension. Chest 129, 1636–1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, MacLean MR, Jeffery TK, Morecroft I, Yang X, Rudarakanchana N, Southwood M, James V, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. (2006). Serotonin increases susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in BMPR2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 98, 818–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long L, Crosby A, Yang X, Southwood M, Upton PD, Kim DK, Morrell NW. (2009). Altered bone morphogenetic protein and transforming growth factor-beta signaling in rat models of pulmonary hypertension: potential for activin receptor-like kinase-5 inhibition in prevention and progression of disease. Circulation 119, 566–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado RD, Aldred MA, James V, Harrison RE, Patel B, Schwalbe EC, Gruenig E, Janssen B, Koehler R, Seeger W, et al. (2006). Mutations of the TGF-beta type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum Mutat. 27, 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri FA, Xu W, Comhair SA, Asosingh K, Koo M, Vasanji A, Drazba J, Anand-Apte B, Erzurum SC. (2007). Hyperproliferative apoptosis-resistant endothelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 293, L548–L554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurtry MS, Bonnet S, Michelakis ED, Haromy A, Archer SL. (2007). Statin therapy, alone or with rapamycin, does not reverse monocrotaline pulmonary arterial hypertension: the rapamcyin-atorvastatin-simvastatin study. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 293, L933–L940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchaers KT, Schalij I, Versteilen AM, Hadi AM, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, van Hinsbergh VW, Postmus PE, van der Laarse WJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. (2009). Endothelin receptor blockade combined with phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition increases right ventricular mitochondrial capacity in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 297, H200–H207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Faul JL, Berry GJ, Vaszar LT, Qiu D, Pearl RG, Kao PN. (2002). Simvastatin attenuates smooth muscle neointimal proliferation and pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 166, 1403–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Vaszar LT, Faul JL, Zhao G, Berry GJ, Shi L, Qiu D, Benson G, Pearl RG, Kao PN. (2003). Simvastatin rescues rats from fatal pulmonary hypertension by inducing apoptosis of neointimal smooth muscle cells. Circulation 108, 1640–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata H, Sakai Y, Ohnishi S, Takeshita S, Mori H, Kodama M, Kangawa K, Aizawa Y, Nagaya N. (2008). Single injection of a sustained-release prostacyclin analog improves pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 177, 195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan LC, Wilson DW, Segall HJ. (1993). Strain differences in the response of Fischer 344 and Sprague-Dawley rats to monocrotaline induced pulmonary vascular disease. Toxicology 79, 21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozeg ZI, Michelakis ED, McMurtry MS, Thebaud B, Wu XC, Dyck JR, Hashimoto K, Wang S, Moudgil R, Harry G, et al. (2003). In vivo gene transfer of the O2-sensitive potassium channel Kv1.5 reduces pulmonary hypertension and restores hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in chronically hypoxic rats. Circulation 107, 2037–2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovitch M. (2001). Linking a serotonin transporter polymorphism to vascular smooth muscle proliferation in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 108, 1109–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runo JR, Loyd JE. (2003). Primary pulmonary hypertension. Lancet 361, 1533–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Satoh A. (2008). 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl (HMG)-COA reductase inhibitors and phosphodiesterase type V inhibitors attenuate right ventricular pressure and remodeling in a rat model of pulmonary hypertension. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 11, 118s–130s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savale L, Tu L, Rideau D, Izziki M, Maitre B, Adnot S, Eddahibi S. (2009). Impact of interleukin-6 on hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension and lung inflammation in mice. Respir Res 10, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, Elliott CG, Gaine SP, Gladwin MT, Jing ZC, et al. (2009). Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 54, S43–S54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Jones JE, Beppu H, Keaney JF, Jr, Loscalzo J, Zhang Y-Y. (2005). Increased susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Circulation 112, 553–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y, Coleman L, Shi J, Beppu H, Sato K, Walsh K, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY. (2008). Inflammation, endothelial injury, and persistent pulmonary hypertension in heterozygous BMPR2-mutant mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 295, H677–H690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiekerkoetter E, Alvira CM, Kim YM, Bruneau A, Pricola KL, Wang L, Ambartsumian N, Rabinovitch M. (2008). Reactivation of gammaHV68 induces neointimal lesions in pulmonary arteries of S100A4/Mts1-overexpressing mice in association with degradation of elastin. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 294, L276–L289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbrook HS, Morris KG, McMurtry IF. (1984). Prevention and reversal of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension by calcium antagonists. Am Rev Resp Dis. 130, 81–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner MK, Syrkina OL, Kolliputi N, Mark EJ, Hales CA, Waxman AB. (2009). Interleukin-6 overexpression induces pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res 104, 236–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark KR, Davie N, Frid M, Gerasimovskaya E, Das M. (2006). Role of the adventitia in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Physiology (Bethesda) 21, 134–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenmark KR, Meyrick B, Galie N, Mooi WJ, McMurtry IF. (2009). Animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the hope for etiological discovery and pharmacological cure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 297, L1013–L1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Kasahara Y, Alger L, Hirth P, McMahon G, Waltenberger J, Voelkel NF, Tuder RM. (2001). Inhibition of the VEGF receptor 2 combined with chronic hypoxia causes cell death-dependent pulmonary endothelial cell proliferation and severe pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. 15, 427–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Scerbavicius R, Choe K-H, Cool C, Wood K, Tuder RM, Burns N, Kasper M, Voelkel NF. (2006). Simvastatin causes endothelial cell apoptosis and attenuates severe pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 291, L668–L676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Docx C, Holmes AM, Beach S, Duggan N, England K, Leblanc C, Lebret C, Schindler F, Raza F, et al. (2009). Activin-like kinase 5 (ALK5) mediates abnormal proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells from patients with familial pulmonary arterial hypertension and is involved in the progression of experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension induced by monocrotaline. Am J Pathol. 174, 380–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuder RM, Groves B, Badesch DB, Voelkel NF. (1994). Exuberant endothelial cell growth and elements of inflammation are present in plexiform lesions of pulmonary hypertension. Am J Pathol. 144, 275–285 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Albada ME, van Veghel R, Cromme-Dijkhuis AH, Schoemaker RG, Berger RM. (2006). Treprostinil in advanced experimental pulmonary hypertension: beneficial outcome without reversed pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 48, 249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Wang J, Zhao L, Wang Y, Liu J, Shi L, Xu M. (2008). Sildenafil inhibits human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation by decreasing capacitative Ca2+ entry. J Pharmacol Sci. 108, 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West J, Fagan K, Steudel W, Fouty B, Lane K, Harral J, Hoedt-Miller M, Tada Y, Ozimek J, Tuder R, et al. (2004). Pulmonary hypertension in transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative BMPRII gene in smooth muscle. Circ Res. 94, 1109– 1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RJ, Meoli DF, Swarthout RF, Kallop DY, Galaria II, Harvey JL, Miller CM, Blaxall BC, Hall CM, Pierce RA, et al. (2007). Plexiform-like lesions and increased tissue factor expression in a rat model of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 293, L583–L590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PB, Deng DY, Beppu H, Hong CC, Lai C, Hoyng SA, Kawai N, Bloch KD. (2008). Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type II receptor is required for BMP-mediated growth arrest and differentiation in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 283, 3877–3888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Keller SH, Remillard CV, Safrina O, Nicholson A, Zhang SL, Jiang W, Vangala N, Landsberg JW, Wang JY, et al. (2009). A functional single-nucleotide polymorphism in the TRPC6 gene promoter associated with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 119, 2313–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JX, Aldinger AM, Juhaszova M, Wang J, Conte JV, Jr, Gaine SP, Orens JB, Rubin LJ. (1998). Dysfunctional voltage-gated K+ channels in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells of patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 98, 1400–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Mason NA, Morrell NW, Kohonazarov B, Sadykov A, Maripov A, Mirrakhimov MM, Aldashev A, Wilkins MR. (2001). Sildenafil inhibits hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 104, 424–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Sebkhi A, Ali O, Wojciak-Stothard B, Mamanova L, Yang Q, Wharton J, Wilkins MR. (2009). Simvastatin and sildenafil combine to attenuate pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 34, 948–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zierer A, Voeller RK, Melby SJ, Steendijk P, Moon MR. (2009). Impact of calcium-channel blockers on right heart function in a controlled model of chronic pulmonary hypertension. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 26, 253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]