The cause of the sudden infant death syndrome is unclear. Polygraphic recordings of 30 infants who subsequently died of the syndrome showed a significant increase in mixed and obstructive apnoeas compared with well matched controls.1 Postmortem examination suggests upper airway narrowing in victims of the syndrome. The decreased number of cases of sudden infant death syndrome after advice to put infants to sleep supine suggests a posture dependent cause, and recent evidence suggests that upper airways of sleeping infants are more widely patent supine than prone.2 Thus sleeping supine might decrease obstructive apnoeas.

An increased frequency of sudden infant death syndrome and apparent life threatening events in infants has been found in the families of patients with the obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome.3,4 We found that retroposition of the maxilla was a common feature in families who had both the obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea and sudden infant death syndromes.3 We also found that obstructive apnoeas in adult family members of patients with the obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome were related to retroposition of the maxilla and mandible.5

We therefore tested the hypothesis that victims of the sudden infant death syndrome have backset maxillae and mandibles, which would predispose them to narrowing and occlusion of their upper airways.

Subjects, methods, and results

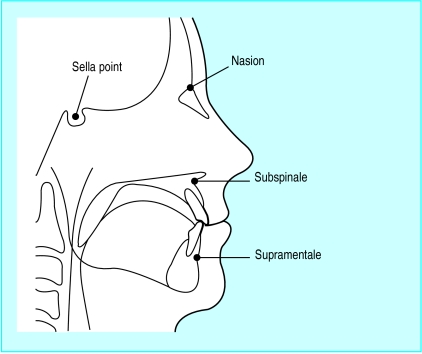

We examined differences in facial bone structure between 15 consecutive victims of the sudden infant death syndrome and 15 control infants who had died of explained causes. Each case was matched to a control infant aged within one postnatal month of the case (mean age 5 months, range 1-10 months). Lateral cephalographs taken at necropsy were examined for the maxillary position (the sella-nasion-subspinale angle) and the mandibular position (the sella-nasion-supramentale angle) (figure). These two angles have been shown to differ between first degree relatives of patients with sleep apnoea and the normal population.5 Measurements were recorded twice for each subject by one observer blind to cause of death, and the average values were taken. The coefficient of variation for repeat measurements within individuals was 0.4% (range 0-1%) for the maxillary angle and 0.4% (0-2%) for the mandibular angle. Differences between cases and controls were determined with Wilcoxon’s rank sum test for paired differences. Significance was taken as P<0.05.

There was no difference in body weight between the cases and controls (5.7 kg (SE 1.0) v 5.7 kg (0.5)). The cases had significantly smaller maxillary angles than the controls (median 82° (95% confidence interval 79° to 85°) v 84° (83° to 90°), P=0.01). There was a trend for the mandibular angle to be smaller in the cases than in the controls (71° (67° to 74°) v 75° (70° to 77°), P=0.1).

Comment

This study shows that victims of the sudden infant death syndrome had different facial structure compared with control infants, with retroposition of the maxilla that might predispose to retropalatal upper airway narrowing. Since facial structure is at least partly inherited, this may provide the familial link in the sudden infant death syndrome, although larger studies are required to confirm these findings. These results also provide a further link between the sudden infant death and obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndromes, as the facial changes are similar in both conditions.

Our study indicates that a retrognathic facial structure should be considered as an additional risk factor for the sudden infant death syndrome, and the suggested mechanism for upper airway narrowing could also contribute to the posture dependence of the syndrome and to the association with upper respiratory tract infections, which predispose to obstructive apnoeas by increasing nasal resistance. We suggest there is a need to assess whether prevention of obstructive apnoeas, such as by continuous positive airway pressure, prevents the sudden infant death syndrome in high risk infants.

Figure.

Skeletal reference points on schematic lateral cephalometric radiograph. Sella point is the midpoint of the sella turcica, the nasion is the most anterior point of the frontonasal suture, the subspinale is the most posterior point on the anterior contour of the upper alveolar process, and the supramentale is the most posterior point on the anterior contour of the lower alveolar process

Footnotes

Funding: KR was funded by ResMed during this study.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Kahn AA, Groswasser J, Rebuffat E, Sottiaux M, Blum D, Foerster M, et al. Sleep and cardiorespiratory characteristics of infant victims of sudden death: a case control study. Sleep. 1992;15:287–292. doi: 10.1093/sleep/15.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skatvedt O, Grogaard J. Infant sleeping position and inspiratory pressures in the upper airways and oesophagus. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:138–140. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathur R, Douglas NJ. Relationship between sudden infant death syndrome and adult sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Lancet. 1994;334:819–820. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tishler PV, Redline S, Ferrette V, Hans MG, Altose MD. The association of sudden unexpected infant death with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:1857–1863. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.6.8665046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathur R, Douglas NJ. Family studies in patients with the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:174–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-3-199502010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]