Abstract

The pathologies of major neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease have been well known for decades. More recently, advances in molecular genetics have suggested important mechanistic links between the pathology of these disorders and pathogenesis of neuronal dysfunction and death. Numerous animal models have been produced based on the new information emerging from human genetic studies. As a complement to traditional mouse models, a number of investigators have modeled neurodegenerative diseases in simple model organisms ranging from yeast to Drosophila. These simple genetic models often display remarkable pathological similarities to their cognate human disorders, and genetic and biochemical studies have yielded important insights into the pathogenesis of the human disorders. Use of these tractable simple models may become even more important as large amounts of genetic data emerge from genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and other neurodegenerative disorders.

Degenerative diseases of the nervous system are common, devastating to patients and families, and essentially untreatable. Alzheimer disease is the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder and affects about 10% of people over the age of 70.1 Parkinson disease is next in frequency, with a prevalence of approximately 2% of individuals over the age of 70.2,3 Advancing age is the most important risk factor for Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and related neurodegenerative disorders. Because the population of the United States is aging, neurodegenerative diseases will represent an increasing burden on individuals, families, and the health care system in the coming years.

Fortunately, the advent of molecular genetics has facilitated important insights into the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, with critical progress first emerging in rare neurodegenerative disorders. Localization of the gene for Huntington disease to the short arm of chromosome 4 by James Gusella and coworkers using anonymous DNA markers was an early landmark application of molecular genetic technology to the study of neurodegenerative disease.4 Ten years later the same group reported the molecular cloning of the locus, revealing that huntingtin is a very large (>350-kDa) novel protein of unknown function.5 Cloning of the Huntington disease gene provided significant insight into the pathogenesis of the disorder: CAG trinucleotide expansion occurs within the gene. When an allele has expanded sufficiently (>34 units), neurodegeneration ensues.

Understanding the fundamental genetic basis of Huntington disease provided the knowledge and tools needed to create models of the disorder. Two approaches were taken initially. First, the mouse homolog of the Huntington disease gene was inactivated. Mice completely lacking gene function or having reduced levels of huntingtin die in early embryogeneis.6,7 Although these findings leave open the possibility that loss of Huntington disease gene function contributes to some aspect of the disorder,8,9 simply reducing gene function does not provide a good model for the disorder. In contrast, mice that overexpress mutant polyglutamine-expanded (the nucleotide triplet CAG encodes glutamine) forms of huntingtin have progressive neurological phenotypes, and in some models, neuronal cell loss and early death.10

Murine models of Huntington disease based on expression of mutant forms of human or mouse huntingtin have been used extensively to test hypotheses regarding the pathogenesis of the disorder and to assess candidate therapeutics. Despite the undoubted utility of vertebrate animal models like Huntington disease transgenic mice, certain experimental approaches, particularly genetic ones, are limited by the time and expense of breeding and maintaining mice. In contrast, simple invertebrate models can be used for genome-wide forward genetic analyses, drug screens, and other higher throughput approaches. Thus, once the principles of polyglutamine pathogenesis had been established using human molecular genetics and mouse modeling, invertebrate models were created using a similar approach. Transgenic flies, worms, and yeast were created that expressed mutant polyglutamine-expanded versions of huntingtin.11,12,13 These models all replicated substantial toxicity of mutant huntingtin.

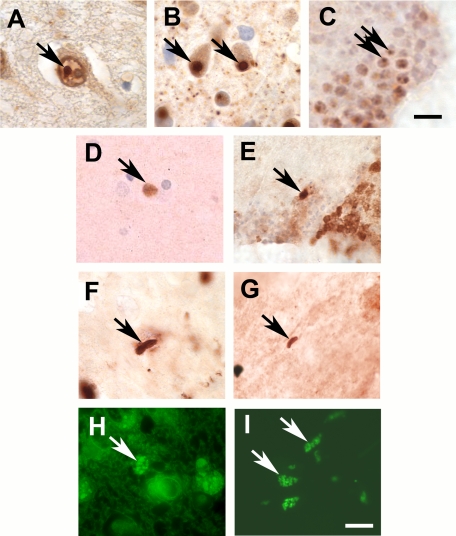

In addition, invertebrate models proved an excellent system in which to study another feature of Huntington disease: abnormal protein aggregation. Although the presence of intranuclear inclusions had been described in Huntington disease by electron microscopy previously,14 identification of huntingtin and the subsequent development of antibodies recognizing the protein led to the description of significant intranuclear and neuritic aggregation of mutant huntingtin in the brains of affected patients (Figure 1A).15 Animal models of the disorder, including simple genetic models, recapitulate the abnormal aggregation of mutant huntingtin (Figure 1, B and C). We now know that Huntington disease is only one example of a group of disorders caused by expansion of a CAG repeat that encodes a polyglutamine stretch within the host protein. Other polyglutamine disorders include spinal bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA), and six types of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 17). These are all Mendelian genetic disorders with dominant inheritance, and are all thought to be caused by a dominant gain of function mechanism reflecting toxicity, perhaps through abnormal aggregation, of the expanded polyglutamine protein sequences.16

Figure 1.

Neurodegenerative disease pathology in patients and flies. A: Intranuclear inclusion in a patient with Huntington disease (arrow). B: Intranuclear inclusions in a mouse model of Huntington disease (arrows). C: Intranuclear inclusions in a fly model of Huntington disease (arrows). D: Cortical-type Lewy body in a patient with Parkinson disease (arrow). E: α-synuclein immunoreactive Lewy body–like inclusion in a fly model of Parkinson disease (arrow). F: Actin-immunostained Hirano body in a patient with Alzheimer disease (arrow). G: Actin-rich Hirano body–like inclusions in a fly model of Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies (arrow). H: Neuronal ceroid lipofuscin in a patient with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis and a mutation in the cathepsin D gene (arrow). I: Autofluorescent pigement in neurons from a fly lacking cathepsin D (arrows). Scale bar in C is 5 μm. Scale bar in I and all other panels is 10 μm.

A number of comprehensive genetic and chemical screens have been carried in simple genetic models of Huntington disease and related polyglutamine expansion disorders. Many of these screens have provided strong evidence for a causative role for protein aggregation in the disorders,17,18,19 although the precise species of toxic aggregate remains undefined. In addition, novel therapeutic pathways have emerged from genetic studies in model organisms. Pioneering work from Leslie Thompson’s group demonstrated a role for mutant huntingtin in control of histone acetylation and further showed that inhibiting histone deacetylases provided therapeutic benefit to flies expressing mutant huntingtin.20 These findings have been replicated in vertebrate models of polyglutamine toxicity, and histone deacetylase inhibitors are promising therapeutic compounds in the human diseases.21

Although the ability to model the toxicity and abnormal aggregation of polyglutamine disorders successfully in simple genetic model organisms suggested some utility for the approach, it was not initially clear that similar success would obtain for more common neurodegenerative diseases. Most cases of Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease do not have an obvious genetic basis. However, like the polyglutamine disorders, both Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease are characterized by the presence of abnormal protein aggregates in affected brain tissue: amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and Hirano bodies in Alzheimer disease, and Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in Parkinson disease.

Significant encouragement was given to the idea of creating simple genetic models of Parkinson disease in 1997 when genetic cloning of the first Parkinson disease gene was reported.22,23 The autosomal dominant PARK1 locus encodes α-synuclein, an abundant neuronal protein of unknown function. So far, three missense mutations linked to familial Parkinson disease have been identified in α-synuclein: A53T, A30P, and E46K.24 Missense mutations in α-synuclein are a very rare cause of Parkinson disease; however, the identification of α-synuclein mutations has been remarkably informative. Description of mutations in the α-synuclein gene quickly led to the discovery that α-synuclein is a major protein component of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites (Figure 1D).25,26 Because these inclusion bodies are present not only in the rare patient carrying mutations in the α-synuclein gene, but in sporadic Parkinson disease as well, substantial support was given to the hypothesis that α-synuclein may play a critical role in both genetic and sporadic forms of the disorder.

Taking a cue from the work on Huntington disease and related polyglutamine disorders, a number of investigators overexpressed normal and mutant versions of human α-synuclein in experimental animals to model Parkinson disease. In addition to the Drosophila model developed in our laboratory and discussed in detail below, expression of human α-synuclein in yeast,27,28 C. elegans,29 mice,30,31,32 rats,33,34 and monkeys35 has provided a number of models of Parkinson disease. Many of these models replicate key biochemical and cell biological features of Parkinson disease and show significant promise in furthering the understanding of Parkinson disease pathogenesis and the development of therapies for the disorder. As in Huntington disease and related polyglutamine expansion diseases, knocking out α-synuclein in mice does not provide a faithful model of Parkinson disease.36

When we expressed wild-type or Parkinson disease–linked mutant forms of human α-synuclein in Drosophila we observed age-dependent degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and progressive locomotor dysfunction.37 Although mutant forms of α-synuclein (A30P, A53T) were somewhat more toxic that wild-type α-synuclein, we observed very similar pathologies when expressing either wild-type or mutant versions of the protein. These findings are consistent with a critical role for α-synuclein in both genetic and sporadic forms of the disorder, and suggest that increased expression of the protein may underlie neurotoxicity. Indeed, the recent description of duplications and triplications of the α-synuclein locus in familial Parkinson disease38 lends strong support to the hypothesis that wild-type α-synuclein can cause neuronal death and dysfunction in patients when levels of the protein are elevated.

As for the polyglutamine disorders, modeling in Drosophila also recapitulates abnormal aggregation of the overexpressed protein. Flies expressing wild-type or mutant human α-synuclein develop α-synuclein–rich intraneuronal inclusion bodies with advancing age (Figure 1E). These inclusions form in both neuronal cell bodies and in neuritic processes. At the electron microscopic level the inclusions are filamentous and resemble cortical-type Lewy bodies from Parkinson disease patients.37 Work in simple model organisms has contributed substantially to understanding the relationship of Lewy pathology to the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Soon after the development of the α-synuclein transgenic fly model of Parkinson disease, expression of human HSP70 was reported to ameliorate neurotoxicity of the protein,39,40 implicating abnormal protein folding in pathogenesis. α-synuclein is one of a number of aggregation prone proteins that are natively unstructured but have a propensity to form β sheet secondary structure as part of the aggregation process.41

Subsequent studies have shown that aggregation of α-synuclein is strongly dependent on phosphorylation of the protein. α-synuclein is a natively unstructured molecule of 140 amino acids that can be divided into three distinct domains (Figure 2). The highly conserved N terminus contains imperfect repeats including the sequence motif KTKEGV. The three missense mutations linked to familial Parkinson disease lie within the repeat region. The central nonamyloid component (NAC) region of α-synuclein is relatively hydrophobic, whereas the C-terminal tail is acidic. Many of the documented phosphorylation sites are in the acidic tail. Serine 129 is extensively phosphorylated in brain tissue from patients with Parkinson disease and in α-synuclein transgenic mouse models,42,43,44 suggesting a role for serine 129 phosphorylation in disease pathogenesis. We have tested the role of serine 129 phosphorylation in our Drosophila model of Parkinson disease and found that phosphorylation at serine 129 is a key mediator of dopaminergic toxicity and α-synuclein aggregation.45 Importantly, we found that the formation of large Lewy body-like inclusion bodies correlated with neuroprotection rather than neurotoxicity.

Figure 2.

α-Synuclein sequence motifs.

To clarify the role of α-synuclein aggregation in neurotoxicity we then deleted the 11 amino acids that constitute the central NAC domain (Figure 2). Prior studies had demonstrated that the NAC domain was essential for aggregation of α-synuclein in vitro.46,47,48 We confirmed that the NAC domain is required for aggregation in vivo because flies expressing α-synuclein without NAC did not form large aggregates.49 Importantly, we were also able to identify soluble oligomeric species biochemically. These oligomeric species also required NAC sequences. Animals unable to form either oligomeric assemblies or large Lewy-body like aggregates showed no toxicity of α-synuclein to dopaminergic neurons.

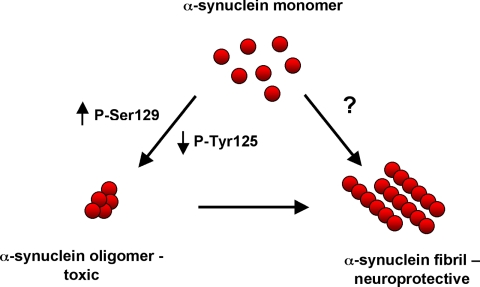

These findings strongly implicate abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein in mediating neurotoxicity, but do not clearly define the species of aggregate responsible for the deleterious effects of the protein. To address this issue we extended our prior analysis of α-synuclein phosphoryation. In addition to serine phosphorylation, α-synuclein can also be phosphorylated at three C-terminal tyrosine residues: tyrosine 125, 133, and 136.50,51 In contrast to the neurotoxic effect of phosphorylation at serine 129, we see a neuroprotective effect for tyrosine phosphorylation. Most importantly, we found that the levels of soluble oligomers correlated with neurotoxicity in flies with increases or decreases in serine or tyrosine phosphorylation of α-synuclein (Figure 3).51 These findings correlate well with recent work from Karpinar et al52 in which a series of α-synuclein point mutations were assayed for their ability to form oligomers and fibrils in vitro and neurotoxicity in vivo using Drosophila and C. elegans models of α-synuclein dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Similar to work in our laboratory, formation of oligomeric species correlated with toxicity, whereas aggregation into higher order fibrillar species was neuroprotective. These data all together are consistent with a model in which prefibrillar species of α-synuclein are toxic. Levels of these toxic species can be elevated by increasing the total amount of α-synuclein, or by specific posttranslational modifications. Other posttranslation modifications may promote formation of fibrillar species that then aggregate into large Lewy body inclusions. Fibrils and the subsequent accumulation of fibrils into Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites may constitute a protective cellular response (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Model for aggregation and toxicity of α-synuclein.

The importance of posttranslational modifications in determining neurotoxicity of aggregation-prone proteins has also become apparent in experimental models of Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. Neurofibrillary tangles, one of the major pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer disease, comprise abnormally hyperphosphorylated and aggregated tau protein.53,54,55 In addition, pathological protein aggregates in Alzheimer disease include extracellular amyloid plaques, which are composed of short Aβ peptides derived from the larger amyloid precursor protein. Hirano bodies are a lesser known, although frequent, pathological concomitant of Alzheimer disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. These eosinophilic, rod-shaped inclusions are rich in actin (Figure 1F), contain cofilin, and bind phalloidin.56 Although all three types of protein aggregates are present in the brains of patients with Alzheimer disease, neurofibrillary aggregates (neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic threads) are the sole type of inclusion body in several less common neurodegenerative diseases, including progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick disease, and corticobasal degeneration.57 Neurodegenerative disorders characterized by significant tau pathology are often characterized as “tauopathies.”

Although the presence of hyperphosphorylated tau in neurofibrillary tangles has been well recognized for a number of years, there was for some time significant debate regarding the relationship of tau and neurofibrillary tangles to disease pathogenesis. In 1998 several groups described mutations in the tau gene in patients with the autosomal dominant familial tauopathy frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17).58,59,60 These genetic findings strongly supported a causal role for tau in mediating neurodegeneration. In addition, the genetic information suggested an animal modeling strategy: express wild-type and FTDP-17–linked mutant forms of human tau. A number of such models have been made in vertebrate and invertebrate model systems.61,62 In our laboratory we created a tauopathy model in Drosophila that recapitulates critical features of human tauopathies, including shortened lifespan, progressive neurodegeneration, and accumulation of abnormally folded and phosphorylated tau.63 Mutant tau is more toxic than wild-type tau.

The ability to perform unbiased forward genetic screens is one of the key advantages of Drosophila as a model system to study the pathogenesis of human neurodegenerative diseases. A number of years ago we performed a genetic screen for modifiers of tau toxicity using a simple and robust retinal toxicity assay.64 Remarkably, the largest single class of genetic modifiers we recovered was related to protein phosphorylation. In general, increasing kinase activity enhanced tau toxicity, whereas increasing phosphatase activity ameliorated the deleterious effects of tau expression. These genetic findings, together with similar results from other laboratories using tau transgenic Drosophila62,65 (see also Chatterjee et al66), supported a role for tau phosphorylation in playing a causal role in mediating neurotoxicity. However, potential kinase and phosphatase targets other than tau have complicated definitively demonstrating that tau hyperphosphorylation mediates neurotoxicity in vertebrate model systems.67 In transgenic mice, expression of the cdk5 activator p25,68 cdk5 together with p25,69 a dominant negative form of protein phosphatase 2A,70 or glycogen synthase kinase 371,72 results in hyperphosphorylation of tau, but effects on neurodegenerative cell death have been variable. Some of the variable results could also be attributable to differential effects on specific phosphorylation sites. Tau can be phosphorylated on at least 30 serine or threonine residues.73 Although antibodies recognizing selected tau phosphoepitopes show relatively specific staining of tau from Alzheimer disease brain tissue,74,75,76 the role of particular phosphorylation sites in mediating tau neurotoxicity has been undefined.

To address the selectivity of kinase and phosphatase modifiers, and to determine which phosphorylation sites on tau are critical for in vivo toxicity, we expressed a series of mutant versions of tau in Drosophila. Transgenesis techniques are well developed in Drosophila, and the short generation time means that a relatively large number of transgenic constructs can be assayed for their effects in vivo in a relatively short period of time. We focused first on a group of 14 serine and threonine residues that are followed by a proline, so called “S/P” and “T/P” sites. These sites include many of those that show relative disease specificity. When we mutated all 14 of these sites to alanine to prevent phoshorylation, neurotoxicity of tau was significantly reduced.77 Conversely, when we altered all 14 sites to the negatively charged amino acid glutamate to mimic phosphorylation, toxicity of tau was markedly enhanced.78 Importantly, kinase modifiers failed to enhance phosphorylation site mutant tau, supporting a role for these kinases in promoting tau neurotoxicity by phosphorylating tau directly in vivo.77 To more precisely pinpoint the phosphorylation sites required for tau neurotoxicity, we made an additional series of transgenic fly strains in which phosphorylation of tau was blocked at one or two residues. Somewhat surprisingly given the implication of particularly residues in tau neurotoxicity by descriptive studies, we did not find that blocking phosphorylation at individual sites or pairs of sites substantially altered neurotoxicity of the protein in vivo. These findings suggest that although phosphorylation of tau is a critical mediator of neurotoxicity in vivo, individual phosphorylation events cooperate to enhance toxicity of the protein.79 Thus, therapeutic efforts that seek to find treatments for Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies by inhibiting kinases may need to target multiple phosphorylation sites on the tau molecule.

The mechanisms transducing the neurotoxicity of abnormally phosphorylated tau are of significant interest from both a scientific and therapeutic perspective. Taking cues from the genetic modifiers of tau toxicity that we originally identified,64 we have defined a number of such pathways. While tau is a microtubule binding protein and a number of lines of evidence have associated the ability of tau to bind microtubules with the propensity of the protein to aggregate and show toxicity, we became intrigued by preliminary genetic evidence that tau might interact with the actin cytoskeleton as well.64 We were particularly interested in a potential role for abnormalities in the actin cytoskeleton in Alzheimer disease because the Hirano body, a characteristic neuropathological feature of Alzheimer disease, is highly enriched for actin. We found that tau could stabilize actin both in vivo and in vitro.80 Significantly, we observed that expression of human tau can drive the formation of actin-rich Hirano body–like structures both in transgenic flies and in mice expressing human tau (Figure 1G).80 One of the major strengths of Drosophila as a model system is the ability to test the causal role of genes and pathways in a comprehensive fashion using genetics. We thus found that stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton using genetic manipulation enhanced the toxicity of tau while reducing the stability of actin filaments suppressed neurotoxicity.

The role of oxidative stress in mediating neuronal death and dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases has been the subject of some controversy. While numerous descriptive studies have documented evidence of oxidative stress in patient tissue, whether markers of oxidative stress are a secondary consequence of neurodegeneration, or play a causal role in the process has been unclear.81 We have taken a genetic approach to address the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease and related neurodegenerative tauopathies. We found that genetic and pharmacological activation of antioxidant defense mechanisms significantly suppressed the neurotoxicity of tau in transgenic Drosophila, strongly supporting a causal role for oxidative stress in tau-mediated neurodegeneration.82

Oxidative stress has been linked to cell cycle activation.83 Intriguingly, a number of studies have described aberrant neuronal expression and localization of cell cycle proteins in postmortem tissue from patients with Alzheimer disease and other tauopathies,84 and even DNA replication in Alzheimer disease neurons.85 However, these observations have not directly addressed a causal role for cell cycle activation in mediating neurodegeneration. As with oxidative stress, we took a genetic approach to the problem. The cell cycle machinery, like most basic cellular pathways, is highly conserved from Drosophila to vertebrates. We could thus genetically manipulate fly homologs of the cell cycle proteins re-expressed in the Alzheimer disease brain. With such genetic manipulations we provided strong support for a causal role for re-entry of postmitotic neurons into a cycling state and death of those neurons. We further demonstrated that cell cycle activation is mediated through activation of the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway, a highly conserved growth-controlling signaling cassette.78

We have therefore defined a number of critical cellular pathways that mediate neurodegeneration in tau transgenic Drosophila: actin stabilization, oxidative stress, and abnormal reactivation of the cell cycle. For a complete understanding of pathogenesis, and to guide therapy development, we would like to understand the relationship of these pathways to one another. Does phosphorylation lead to cell cycle activation, or conversely do the changes in kinase and phosphatase activity that accompany cell cycle activation promote tau hyperphosphorylation? Do the components of the pathways act sequentially, or does tau influence multiple cellular pathways in parallel? Genetic model organisms like Drosophila provide an excellent opportunity to address such questions of epistasis. With regard to tau, we have used multiple experimental approaches to show that phosphorylation is upstream, and required for, stabilization of actin, sensitivity to oxidative stress, activation of the TOR pathway, and promotion of abnormal cell cycle activation in postmitotic neurons.

It seems plausible that tau can influence multiple pathways in the cell, and that at least some of these pathways may act in parallel to mediate neurotoxicity. However, we have evidence that at least some critical control points exist. Using mutations that eliminate approximately 90% of two critical components of the TOR pathway, S6K and TOR itself, we demonstrated that tau neurotoxicity was almost complete blocked.78 These findings suggest that if parallel pathways exist at the level of TOR-mediated cell cycle activation, those pathways contribute little to neurodegeneration. From a therapeutic perspective, such a critical point in the neurotoxicity cascade would be an attractive target for intervention.

We have thus defined several cellular events downstream of tau phosphorylation that are critical for the expression of neurodegenerative toxicity. What then directs the aberrant activity of kinases and phosphatases that leads to hyperphosphorylation of tau? Although a complete understanding of these important processes awaits further investigation, it is worth noting that an important trigger of tau hyperphosphorylation is likely to be Aβ itself. The presence of both Aβ and tau aggregates in Alzheimer disease, but only tau aggregates in less common tauopathies, has led to the popular “amyloid cascade hypothesis.”86,87 The amyloid cascade hypothesis suggests that production of Aβ is the initiating event in Alzheimer disease, and that tau works downstream of Aβ to produce neurotoxicity. Work demonstrating enhanced tau phosphorylation and aggregation on coexpression of Aβ and tau,88 or with injection of Aβ peptide into brains of mice expressing human tau,89 supports phosphorylation of tau as the specific target of Aβ. In our system we see a striking synergistic enhancement of tau neurotoxicity when we coexpress Aβ1-42.80 Importantly, the enhancement of tau by Aβ is entirely dependent on the presence of intact S/P and T/P phosphorylation sites. Thus, work from our group and others is consistent with a model in which Aβ works upstream of tau to enhance the phosphorylation and aggregation of tau. However, the pathways mediating the interaction of Aβ and tau remain substantially undefined, although a variety of hypotheses have been proposed.90 Recapitulation of phosphorylation-dependent synergistic enhancement of tau neurotoxicity by Aβ in a genetically tractable organism now opens the door to a comprehensive genetic approach to defining receptors, signaling molecules, and other factors that transduce the effects of Aβ on tau.

Because the power of genetic analysis to define the basic cellular functions of proteins has been well known for many years, we have spent less time on the topic in the current review. However, it is worth noting that analysis of loss-of-function mutations in Drosophila homologs of human neurodegenerative disease genes has also shown significant promise. For Parkinson disease there are recessive loss of function mutations in several loci that cause familial forms of the disorder. There has been significant interest in determining whether recessive Parkinson disease genes fall in the same genetic pathway. Elegant experiments in Drosophila models of parkin and PINK-1 deficiency have strongly suggested that the two proteins act sequentially to regulate mitochondrial morphology.91,92,93 Because recessive Parkinson disease does not typically manifest with Lewy body pathology, the relationship of these disorders to the more common form of Parkinson disease with Lewy bodies remain to be determined.

In our own laboratory we have modeled the childhood neurodegenerative disorder neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in Drosophila. The neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses are a subtype of lysosomal storage disease characterized by storage of autofluorescent storage material similar to lipofuscin at the light microscopic level (Figure 1H). As a group, they represent the most common progressive neurodegenerative diseases of childhood.94 One form of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the lysosomal protease cathepsin D.95,96 To model the disorder we thus inactivated Drosophila cathepsin D. Flies lacking cathepsin D show striking accumulation of autofluorescent storage material, which increases in abundance with age (Figure 1I).97 Storage material is autofluorescent over a wide range of wavelengths, stains with PAS, and luxol fast blue. By electron microscopy storage material is membrane-bound and forms globular round structures, closely resembling the granular osmiophilic deposits found in the human infantile form of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis.94 Overall, then, storage material in Drosophila missing cathepsin D resembles that found in human neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. The model is thus a powerful one in which to use genetics and pharmacology to explore the mechanisms controlling abnormal storage material in the lysosomal system.

Although most cases of the most common neurodegenerative disorders, Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease, are not inherited in a Mendelian genetic fashion, insights from those diseases that do have a strict genetic basis have been extremely informative. Molecular cloning of the Huntington disease gene provided an important example of neurodegeneration occurring by a toxic dominant gain-of-function mechanism related to abnormal protein aggregation. Further, successful modeling of Huntington disease and related polyglutamine disorders suggested that more common neurodegenerative diseases with fundamentally similar mechanisms of pathogenesis could be modeled by expressing the toxic aggregating protein in experimental model organisms. Creating simple genetic models using the overexpression approach has been widely used, and a number of useful genetic models have been created. These models have helped define the toxic species of some aggregating proteins and have outlined important pathways mediating toxicity. As more and more candidate loci emerge from genome-wide association studies designed to identify common variants in genes that predispose to Alzheimer disease,98 Parkinson disease,99,100 and other neurodegenerative disorders, simple model organisms may play an important role in dissecting the pathways implicated by the new wave of human genetic information.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Mel B. Feany, M.D., Ph.D, Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 77 Avenue Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: mel_feany@hms.harvard.edu.

The ASIP Outstanding Investigator Award is given by the American Society for Investigative Pathology to recognize mid-career investigators with demonstrated excellence in research in experimental pathology. Mel B. Feany, recipient of the 2009 ASIP Outstanding Investigator Award, delivered a lecture entitled “New Approaches to the Pathology and Genetics of Neurodegeneration” on April 20, 2009 at the annual meeting of the American Society for Investigative Pathology in New Orleans, LA.

None of the authors disclosed any relevant financial relationships.

References

- Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Ofstedal MB, Burke JR, Hurd MD, Potter GG, Rodgers WL, Steffens DC, Willis RJ, Wallace RB. Prevalence of dementia in the United States: the aging, demographics, and memory study. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:125–132. doi: 10.1159/000109998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghal S, Rajput AH, Meleth R, D'Arcy C, Rajput R. Prevalence of movement disorders in institutionalized elderly. Neuroepidemiology. 1994;14:297–300. doi: 10.1159/000109805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MK, Shneyder N, Borazanci A, Korniychuk E, Kelley RE, Minagar A. Movement disorders. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:371–388. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusella JF, Wexler NS, Conneally PM, Naylor SL, Anderson MA, Tanzi RE, Watkins PC, Ottina K, Wallace MR, Sakaguchi AY, Young AB, Shoulson I, Bonilla E, Martin JB. A polymorphic DNA marker genetically linked to Huntington disease. Nature. 1983;306:234–238. doi: 10.1038/306234a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Huntington Disease Collaborative Research Group A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir J, Floresco JB, O'Kusky JR, Diewert VM, Richman JM, Zeisler J, Borowski A, Marth JD, Phillips AG, Hayden MR. Targeted disruption of the Huntington disease gene results in embryonic lethality and behavioral and morphological changes in heterozygotes. Cell. 1995;81:811–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyao MP, Auerbach AB, Ryan A, Persichetti F, Barnes GT, McNeil SM, Ge P, Vonsattel JP, Gusella JF, Joyner AL, Macdonald ME. Homozygous inactivation of the mouse Hdh gene does not produce a Huntington disease-like phenotype. Science. 1995;269:407–410. doi: 10.1126/science.7618107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt BR, Guttman JA, Hodgson JG, Kimel GH, Singaraja R, Vogl AW, Hayden MR. Wild-type huntingtin reduces the cellular toxicity of mutant huntingtin in vivo. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:313–324. doi: 10.1086/318207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Feany MB, Saraswati S, Littleton JT, Perrimon N. Inactivation of Drosophila Huntingtin affects long-term adult functioning and the pathogenesis of a Huntington disease model. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2:247–266. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng MY, Detloff PJ, Albin RL. Rodent genetic models of Huntington disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;32:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GR, Salecker I, Dong X, Yao X, Arnheim N, Faber PW, MacDonald ME, Zipursky SL. Polyglutamine-expanded human huntingtin transgenes induce degeneration of Drosophila photoreceptor neurons. Neuron. 1998;21:633–642. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber PW, Alter JR, MacDonald ME, Hart AC. Polyglutamine-mediated dysfunction and apoptotic death of a Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neuron. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Ning K, D'Souza-Schorey C, Fields S. Requirement of an intact microtubule cytoskeleton for aggregation and inclusion body formation by a mutant huntingtin fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:727–732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022628699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizin L, Stellar S, Willson N, Whittier J, Liu JC. Electron microscope and enzyme studies in cerebral biopsies of Huntington chorea. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1974;99:240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, Aronin N. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PO, Nukina N. The pathogenic mechanisms of polyglutamine diseases and current therapeutic strategies. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1737–1765. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Funez P, Nino-Rosales ML, de Gouyon B, She WC, Luchak JM, Martinez P, Turiegano E, Benito J, Capovilla M, Skinner PJ, McCall A, Canal I, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY, Botas J. Identification of genes that modify ataxin-1-induced neurodegeneration. Nature. 2000;408:101–106. doi: 10.1038/35040584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Smith DL, Meriin AB, Engemann S, Russel DE, Roark M, Washington SL, Maxwell MM, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Wanker EE, Young AB, Housman DE, Bates GP, Sherman MY, Kazantsev AG. A potent small molecule inhibits polyglutamine aggregation in Huntington disease neurons and suppresses neurodegeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:892–897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408936102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilen J, Bonini NM. Genome-wide screen for modifiers of ataxin-3 neurodegeneration in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1950–1964. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffan JS, Bodai L, Pallos J, Poelman M, McCampbell A, Apostol BL, Kazantsev A, Schmidt E, Zhu YZ, Greenwald M, Kurokawa R, Housman DE, Jackson GR, Marsh JL, Thompson LM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2001;413:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35099568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang DM, Leng Y, Marinova Z, Kim HJ, Chiu CT. Multiple roles of HDAC inhibition in neurodegenerative conditions. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos T, Johnson WH, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Di Iorio G, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger R, Kuhn W, Müller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kösel S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Schöls L, Riess O. Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding α-synuclein in Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gomez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, Vidal L, Hoenicka J, Rodriguez O, Atares B, Llorens V, Gomez Tortosa E, del Ser T, Munoz DG, de Yebenes JG. The new mutation. E46K, of alpha-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:164–173. doi: 10.1002/ana.10795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba M, Nakajo S, Tu PH, Tomita T, Nakaya K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Iwatsubo T. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies of sporadic Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:879–884. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outeiro TF, Lindquist S. Yeast cells provide insight into alpha-synuclein biology and pathobiology. Science. 2003;302:1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.1090439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham S, Outeiro TF, DeVit MJ, Lindquist SL, Muchowski PJ. Yeast genes that enhance the toxicity of a mutant huntingtin fragment or alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;302:1769–1772. doi: 10.1126/science.1090389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakso M, Vartiainen S, Moilanen AM, Sirviö J, Thomas JH, Nass R, Blakely RD, Wong G. Dopaminergic neuronal loss and motor deficits in Caenorhabditis elegans overexpressing human alpha-synuclein. J Neurochem. 2003;86:165–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Sagara Y, Sisk A, Mucke L. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Duda JE, Quinn SM, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2002;34:521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MK, Stirling W, Xu Y, Xu X, Qui D, Mandir AS, Dawson TM, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL. Human alpha-synuclein-harboring familial Parkinson disease-linked Ala-53 –> Thr mutation causes neurodegenerative disease with alpha-synuclein aggregation in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8968–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132197599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Rosenblad C, Burger C, Lundberg C, Johansen TE, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ, Bjorklund A. Parkinson-like neurodegeneration induced by targeted overexpression of alpha-synuclein in the nigrostriatal system. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2780–2791. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02780.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Bianco C, Ridet JL, Schneider BL, Deglon N, Aebischer P. alpha-Synucleinopathy and selective dopaminergic neuron loss in a rat lentiviral-based model of Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10813–10818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152339799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirik D, Annett LE, Burger C, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ, Bjorklund A. Nigrostriatal alpha-synucleinopathy induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of human alpha-synuclein: a new primate model of Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2884–2889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536383100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abeliovich A, Schmitz Y, Fariñas I, Choi-Lundberg D, Ho WH, Castillo PE, Shinsky N, Verdugo JM, Armanini M, Ryan A, Hynes M, Phillips H, Sulzer D, Rosenthal A. Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron. 2000;25:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Bender WW. A Drosophila model of Parkinson disease. Nature. 2000;404:394–398. doi: 10.1038/35006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson disease. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck PK, Chan HY, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Bonini NM. Chaperone suppression of alpha-synuclein toxicity in a Drosophila model for Parkinson disease. Science. 2002;295:865–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1067389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auluck PK, Bonini NM. Pharmacological prevention of Parkinson disease in Drosophila. Nat Med. 2002;8:1185–1186. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochet JC, Lansbury PT., Jr Amyloid fibrillogenesis: themes and variations. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:60–68. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, Shen J, Takio K, Iwatsubo T. alpha-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:160–164. doi: 10.1038/ncb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Kahle PJ, Giasson BI, Ozmen L, Borroni E, Spooren W, Muller V, Odoy S, Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Iwatsubo T, Trojanowski JQ, Kretzschmar HA, Haass C. Misfolded proteinase K-resistant hyperphosphorylated alpha-synuclein in aged transgenic mice with locomotor deterioration and in human alpha-synucleinopathies. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1429–1439. doi: 10.1172/JCI15777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y, Kawashima A, Ruberu NN, Fujiwara H, Koyama S, Sawabe M, Arai T, Nagura H, Yamanouchi H, Hasegawa M, Iwatsubo T, Murayama S. Accumulation of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein in aging human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:644–654. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Feany MB. Alpha-synuclein phosphorylation controls neurotoxicity and inclusion formation in a Drosophila model of Parkinson disease. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:657–663. doi: 10.1038/nn1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodles AM, Guthrie DJ, Greer B, Irvine GB. Identification of the region of non-Abeta component (NAC) of Alzheimer disease amyloid responsible for its aggregation and toxicity. J Neurochem. 2001;78:384–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Murray IV, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. A hydrophobic stretch of 12 amino acid residues in the middle of alpha-synuclein is essential for filament assembly. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2380–2386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibaee S, Jakes R, Fraser G, Serpell LC, Crowther RA, Goedert M. Sequence determinants for amyloid fibrillogenesis of human alpha-synuclein. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periquet M, Fulga T, Myllykangas L, Schlossmacher MG, Feany MB. Aggregated alpha-synuclein mediates dopaminergic neurotoxicity in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3338–3346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0285-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CE, Schwartzberg PL, Grider TL, Fink DW, Nussbaum RL. alpha-synuclein is phosphorylated by members of the Src family of protein-tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3879–3884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Periquet M, Wang X, Negro A, McLean PJ, Hyman BT, Feany MB. Tyrosine and serine phosphorylation of alpha-synuclein have opposing effects on neurotoxicity and soluble oligomer formation. J Clin Inves. 2009;119:3257–3265. doi: 10.1172/JCI39088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinar DP, Balija MB, Kügler S, Opazo F, Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Wender N, Kim HY, Taschenberger G, Falkenburger BH, Heise H, Kumar A, Riedel D, Fichtner L, Voigt A, Braus GH, Giller K, Becker S, Herzig A, Baldus M, Jäckle H, Eimer S, Schulz JB, Griesinger C, Zweckstetter M. Pre-fibrillar alpha-synuclein variants with impaired beta-structure increase neurotoxicity in Parkinson disease models. EMBO J. 2009;28:3256–3268. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara Y, Nukina N, Miura R, Ogawara M. Phosphorylated tau protein is integrated into paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1986;99:1807–1810. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VM, Balin BJ, Otvos L, Jr, Trojanowski JQ. A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal Tau. Science. 1991;251:675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1899488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano A. Hirano bodies and related neuronal inclusions. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1994;20:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1994.tb00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Dickson DW. Neurodegenerative disorders with extensive tau pathology: a comparative study and review. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:139–148. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, Pickering-Brown S, Chakraverty S, Isaacs A, Grover A, Hackett J, Adamson J, Lincoln S, Dickson D, Davies P, Petersen RC, Stevens M, de Graaff E, Wauters E, van Baren J, Hillebrand M, Joosse M, Kwon JM, Nowotny P, Che LK, Norton J, Morris JC, Reed LA, Trojanowski J, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Neystat M, Fahn S, Dark F, Tannenberg T, Dodd PR, Hayward N, Kwok JB, Schofield PR, Andreadis A, Snowden J, Craufurd D, Neary D, Owen F, Oostra BA, Hardy J, Goate A, van Swieten J, Mann D, Lynch T, Heutink P. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, Andreadis A, Wiederholt WC, Raskind M, Schellenberg GD. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, Van Slegtenhorst M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Paul Murphy M, Baker M, Yu X, Duff K, Hardy J, Corral A, Lin WL, Yen SH, Dickson DW, Davies P, Hutton M. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet. 2000;25:402–405. doi: 10.1038/78078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GR, Wiedau-Pazos M, Sang TK, Wagle N, Brown CA, Massachi S, Geschwind DH. Human wild-type tau interacts with wingless pathway components and produces neurofibrillary pathology in Drosophila. Neuron. 2002;34:509–519. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann CW, Wszolek MF, Shulman JM, Salvaterra PM, Lewis J, Hutton M, Feany MB. Tauopathy in Drosophila: neurodegeneration without neurofibrillary tangles. Science. 2001;293:711–714. doi: 10.1126/science.1062382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman JM, Feany MB. Genetic modifiers of tauopathy in Drosophila. Genetics. 2003;165:1233–1242. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura I, Yang Y, Lu B. PAR-1 kinase plays an initiator role in a temporally ordered phosphorylation process that confers tau toxicity in Drosophila. Cell. 2004;116:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Sang TK, Lawless GM, Jackson GR. Dissociation of tau toxicity and phosphorylation: role of GSK-3beta. MARK and Cdk5 in a Drosophila model. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:164–177. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP. Neuronal death and GSK-3beta: a tau fetish? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:255–256. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01838-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlijanian MK, Barrezueta NX, Williams RD, Jakowski A, Kowsz KP, McCarthy S, Coskran T, Carlo A, Seymour PA, Burkhardt JE, Nelson RB, McNeish JD. Hyperphosphorylated tau and neurofilament and cytoskeletal disruptions in mice overexpressing human p25, an activator of cdk5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2910–2915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040577797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble W, Olm V, Takata K, Casey E, Mary O, Meyerson J, Gaynor K, LaFrancois J, Wang L, Kondo T, Davies P, Burns M, Veeranna, Nixon R, Dickson D, Matsuoka Y, Ahlijanian M, Lau LF, Duff K. Cdk5 is a key factor in tau aggregation and tangle formation in vivo. Neuron. 2003;38:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kins S, Crameri A, Evans DR, Hemmings BA, Nitsch RM, Gotz J. Reduced protein phosphatase 2A activity induces hyperphosphorylation and altered compartmentalization of tau in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38193–38200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittaels K, Van den Haute C, Van Dorpe J, Geerts H, Mercken M, Bruynseels K, Lasrado R, Vandezande K, Laenen I, Boon T, Van Lint J, Vandenheede J, Moechars D, Loos R, Van Leuven F. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta phosphorylates protein tau and rescues the axonopathy in the central nervous system of human four-repeat tau transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41340–41349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JJ, Hernandez F, Gomez-Ramos P, Moran MA, Hen R, Avila J. Decreased nuclear beta-catenin, tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration in GSK-3beta conditional transgenic mice. EMBO J. 2001;20:27–39. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo ES, Shin RW, Billingsley ML, Van deVoorde A, O'Connor M, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Biopsy-derived adult human brain tau is phosphorylated at many of the same sites as Alzheimer disease paired helical filament tau. Neuron. 1994;13:989–1002. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Jakes R, Crowther RA, Lee VM, Ihara Y, Goedert M. Characterization of mAb AP422, a novel phosphorylation-dependent monoclonal antibody against tau protein. FEBS Lett. 1996;384:25–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jicha GA, Lane E, Vincent I, Otvos L, Jr, Hoffmann R, Davies P. A conformation- and phosphorylation-dependent antibody recognizing the paired helical filaments of Alzheimer disease. J Neurochem. 1997;69:2087–2095. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69052087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilb ML, Dias-Santagata D, Mulkearns EE, Shulman JM, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Feany MB. S/P and T/P phosphorylation is critical for tau neurotoxicity in Drosophila. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1271–1278. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana V, Lu Y, Steinhilb ML, Oldham S, Shulman JM, Feany MB. TOR-mediated cell-cycle activation causes neurodegeneration in a Drosophila tauopathy model. Curr Biol. 2006;16:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilb ML, Dias-Santagata D, Fulga TA, Felch DL, Feany MB. Tau phosphorylation sites work in concert to promote neurotoxicity in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:5060–5068. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulga TA, Elson-Schwab I, Khurana V, Steinhilb ML, Spires TL, Hyman BT, Feany MB. Abnormal bundling and accumulation of F-actin mediates tau-induced neuronal degeneration in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:139–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen JK. 2004. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: cause or consequence? Nat Med. 2004;10[Suppl]:S18–S25. doi: 10.1038/nrn1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Santagata D, Fulga TA, Duttaroy A, Feany MB. Oxidative stress mediates tau-induced neurodegeneration in Drosophila. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:236–245. doi: 10.1172/JCI28769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley B, Ratan RR. Oxidative stress-induced death in the nervous system: cell cycle dependent or independent? J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:621–629. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husseman JW, Nochlin D, Vincent I. Mitotic activation: a convergent mechanism for a cohort of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:815–828. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. DNA replication precedes neuronal cell death in Alzheimer disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2661–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL, Chisholm L, Corral A, Jones G, Yen SH, Sahara N, Skipper L, Yager D, Eckman C, Hardy J, Hutton M, McGowan E. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293:1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M, Laferla FM. Pathways by which Abeta facilitates tau pathology. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:437–448. doi: 10.2174/156720506779025242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark IE, Dodson MW, Jiang C, Cao JH, Huh JR, Seol JH, Yoo SJ, Hay BA, Guo M. Drosophila pink1 is required for mitochondrial function and interacts genetically with parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1162–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature04779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lee SB, Lee S, Kim Y, Song S, Kim S, Bae E, Kim J, Shong M, Kim JM, Chung J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Drosophila PINK1 mutants is complemented by parkin. Nature. 2006;441:1157–1161. doi: 10.1038/nature04788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Ouyang Y, Yang L, Beal MF, McQuibban A, Vogel H, Lu B. Pink1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with the fission/fusion machinery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7070–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711845105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltia M. The neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1–13. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siintola E, Partanen S, Stromme P, Haapanen A, Haltia M, Maehlen J, Lehesjoki AE, Tyynela J. Cathepsin D deficiency underlies congenital human neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. Brain. 2006;129:1438–1445. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld R, Reinhardt K, Schreiber K, Hillebrand M, Kraetzner R, Bruck W, Saftig P, Gartner J. Cathepsin D deficiency is associated with a human neurodegenerative disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:988–998. doi: 10.1086/504159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllykangas L, Tyynela J, Page-McCaw A, Rubin GM, Haltia MJ, Feany MB. Cathepsin D-deficient Drosophila recapitulate the key features of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:194–199. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram L, Tanzi RE. Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R137–R145. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Mizuta I, Hirota Y, Ito C, Kubo M, Kawaguchi T, Tsunoda T, Watanabe M, Takeda A, Tomiyama H, Nakashima K, Hasegawa K, Obata F, Yoshikawa T, Kawakami H, Sakoda S, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, Murata M, Nakamura Y, Toda T. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Sanchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, Paisan-Ruiz C, Lichtner P, Scholz SW, Hernandez DG, Krüger R, Federoff M, Klein C, Goate A, Perlmutter J, Bonin M, Nalls MA, Illig T, Gieger C, Houlden H, Steffens M, Okun MS, Racette BA, Cookson MR, Foote KD, Fernandez HH, Traynor BJ, Schreiber S, Arepalli S, Zonozi R, Gwinn K, van der Brug M, Lopez G, Chanock SJ, Schatzkin A, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Gao J, Huang X, Wood NW, Lorenz D, Deuschl G, Chen H, Riess O, Hardy JA, Singleton AB, Gasser T. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]