Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) mediates the ventilator-induced inflammatory response in healthy lungs via angiotensin II (Ang II). A rat model was used to examine the role of ACE and Ang II in the inflammatory response during mechanical ventilation of preinjured (ie, lipopolysaccharide [LPS]-exposed) lungs. When indicated, rats were pretreated with the ACE inhibitor captopril and/or intratracheal administration of LPS. The animals were ventilated for 4 hours with moderate pressure amplitudes. Nonventilated animals served as controls. ACE activity and levels of Ang II and inflammatory mediators (interleukin-6, Cytokine-induced Neutrophil Chemoattractant (CINC)-3, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-10) were determined in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). The localization of ACE and Ang II type 1 receptor in lung tissue was determined by immunohistochemistry. The role of the Ang II pathway was assessed by using its receptor antagonist Losartan. Mechanical ventilation of LPS-exposed animals increased ACE activity and levels of inflammatory mediators in BALF compared with ventilated nonexposed and LPS-exposed nonventilated animals. Blocking ACE by captopril attenuated the lung inflammatory response. Furthermore, increased ACE activity in BALF was accompanied by increased levels of Ang II and enhanced expression of its receptor on alveolar cells. Blocking the Ang II receptor attenuated the inflammatory mediator response to a larger extent than by blocking ACE. In conclusion, during mechanical ventilation ACE, via Ang II, mediates the inflammatory response of both healthy and preinjured lungs.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the most severe form of acute lung injury (ALI) and is characterized by severe hypoxemia, diffuse alveolar injury, pulmonary edema, and an excessive inflammatory response.1 Although mechanical ventilation (MV) can be life-saving for patients with ALI/ARDS, it may induce lung injury, known as ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI), with characteristics similar to that caused by ARDS.2,3,4 Mechanical ventilation of animals with lungs preinjured by intratracheal instillation of bacterial components such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) resulted in markedly higher inflammatory responses compared with ventilated animals without preinjured lungs.5,6,7,8

Clinical and experimental studies found an association between the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and ALI/ARDS.9,10 RAS also plays a key role in the injurious effects of mechanical ventilation.11,12 In healthy rats, inhibition of the RAS component angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) attenuated inflammation and lung injury during mechanical ventilation with high tidal volumes.11 The effect of ACE on the inflammatory response may be explained by the fact that ACE generates the key factor of the RAS, angiotensin II (Ang II). Ang II stimulates expression of proinflammatory mediators such as interleukin-8/Cytokine-induced Neutrophil Chemoattractant (CINC)-3 and interleukin-6 via the type 1 and type 2 Ang II receptors.13,14,15 Indeed, a similar attenuation of the inflammatory response was obtained during injurious mechanical ventilation by blocking the Ang II receptor or by treating with an ACE inhibitor.11,12

The present study investigates whether ACE mediates the exaggerated inflammatory response to mechanical ventilation of LPS-exposed lungs as reflected by inflammatory mediator levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and whether ACE inhibition dampens this response. The role of Ang II in this process was also assessed by using its specific receptor antagonist.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation

The study was approved by the ethical committee for animal experiments of the Erasmus Medical Center. The experiments were performed in a total of 81 male adult Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 270 ± 25 g (Harlan CPB, Zeist, The Netherlands).

A tracheostomy was performed under inhalation anesthesia, and the carotid artery was catheterized. Anesthesia was maintained by hourly intraperitoneal injections of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg · kg−1, Nembutal; Algin BV, Maassluis, The Netherlands). Muscle relaxation was obtained with 2 mg · kg−1 pancuronium bromide (Pavulon; Organon, Boxtel, The Netherlands) intramuscular hourly.

Experimental Protocol

From a group of 18 animals, nine were pretreated with 500 mg l−1 captopril (ACE inhibitor) in their drinking water for 5 days, and nine were not. After preparation, animals were connected to a Servo ventilator 300 (Siemens-Elema, Solar, Sweden) and ventilated for 4 hours in a pressure controlled time-cycled mode with moderate pressure amplitudes: peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) 26 cmH2O and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 5 cmH2O (tidal volume approximately 18 ml/kg). Respiratory rate was set at a frequency of 30 per min (inspiratory/expiratory ratio of 1:2) and, to maintain normocapnia, adjusted when necessary. Because oxygen requirements are usually increased in patients with ALI/ARDS who are mechanically ventilated, we chose to study the effects of ACE inhibition on inflammation in rats ventilated with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 1.0. Blood gas analyses and blood pressure were recorded just before and hourly after randomization. Nonventilated animals (n = 9) served as controls.

To determine whether the effects of ACE inhibition on VILI were changed by the administration of an inflammatory stimulus, an additional group of 18 rats received 16 mg/kg−1 LPS (Salmonella Abortus Equi S form; Metalon BmbH, Wusterhausen, Germany) intratracheally 24 hours before the ventilation period. Of these LPS-exposed rats, nine were pretreated with captopril and nine were not (see above) and all were subsequently ventilated for 4 hours with the same moderate pressure amplitudes as above.

Animals were sacrificed with an overdose of intra-arterial administered pentobarbital sodium. Bronchial lavage was performed (n = 6 per group) five times with normal saline (30 ml/kg−1). The retrieved BALF was centrifuged (300 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes), and the supernatant was stored in aliquots at −80°C. After the lavage, pressure-volume (P/V) characteristics of the lungs in opened chest were determined.16 Lavage was not performed in animals used for histology and immunohistochemistry. From these animals (n = 3 per group), lungs were dissected and recruited by a positive airway pressure of 10 cmH2O, after which they were fixed in 4% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin.

Role of Ang II

To further delineate whether ACE exerted its effects via Ang II, an additional group of nine LPS-exposed rats were pretreated for 5 days with the Ang II type 1 receptor antagonist Losartan (MSD, Haarlem, The Netherlands; 200 mg · l−1 added to the drinking water). Hereafter, the animals were ventilated with the same moderate pressure amplitudes as above. After 4 hours of mechanical ventilation, bronchial lavage (n = 6 per group) was performed. Alternatively, lungs were excised and fixed for histological evaluation (n = 3 per group) as described above.

Assays

Measurement of RAS Components and Inflammatory Mediators

ACE activity was measured in BALF by monitoring the degradation of the fluorogenic peptide substrate Mca-R-P-P-G-F-S-A-F-K(Dnp)-OH (R and D Systems, Uithoorn, The Netherlands) as described previously.11

Ang II was quantified in BALF by using a radioimmunoassay (BioSource, Nivelles, Belgium) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Interleukin-6 was measured by using a rat-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (BioSource). BALF levels of CINC-3, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-10 were measured by using rat Fluorokine MAB assays (R and D Systems) and read with a BioRad Bioplex 100. Finally, total protein was measured by the Bradford method (BioRad Assay, Munich, Germany) by using bovine serum albumin as a reference.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Lung sections were scored for lung injury, including the following: (1) alveolar and capillary edema, (2) intravascular and peri-bronchial influx of inflammatory cells, (3) thickness of the alveolar wall, and (4) hemorrhage. The items were semiquantitatively scored as none, minimal, light, moderate, or severe (score 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4, respectively) by a pathologist blinded to the experimental group. The lung injury score was obtained by averaging the score from the animals within each group.

Immunohistochemical staining for ACE and angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1) in lung tissue was performed by using a monoclonal mouse anti-ACE antibody (clone 2E2, dilution 1:100) and a polyclonal rabbit anti-AT1 antibody (dilution 1:250; both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), respectively. For optimal immunostaining, tissue pretreatments were needed with heat-induced antigen retrieval (20 minutes, 98°C) using either Tris/EDTA, pH 9.0 (ACE) or sodium citrate 10 mmol/L, pH 6.0 (AT1). For staining of AT1, a tyramide signal amplification procedure (Catalyzed System Amplification (CSA) II kit; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was performed according to the vendor’s instructions. ACE and AT1 staining was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Dako) as chromogen. Negative controls, replacing the primary antibodies with irrelevant immunoglobulins (same isotype and concentration), were included.

To identify the ACE- and AT1-positive cells in the alveolar septa, double staining was performed combining anti-ACE and anti-AT1 antibodies (see above) with mouse anti-rat macrophage marker ED-1 (Serotec, Oxford, UK) or mouse-anti broad spectrum cytokeratin (ie, epithelial) marker AE1/AE3 (NeoMarker, Fremont, CA). For double staining a sequential double alkaline phosphatase method was used.17 Briefly, first ACE or AT1 was stained in blue (alkaline phosphatase, Vector Blue) and after an intervening heat step (10 minutes, 98°C), the anti-ED-1 or anti-AE1/AE3 antibody was stained in red (alkaline phosphatase, Dako Liquid Permanent Red).

Quantification for ACE and AT1-positive cells was calculated as the ratio of suitable binary threshold image and the total field area. After immunostaining of AT1 using the brown diaminobenzidine reaction product, tissue sections were counterstained with eosin for marking the total tissue surface. The Nuance Spectral Imaging System 2.4.0 (CRi, Woburn, MA) enables the user to “unmix” both signals based on their spectral characteristics.18 For each sample, the mean staining area was obtained by analysis of 10 different fields (×20), excluding vessels. The staining score is expressed as percent positive area in the total area under examination.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism version 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Group comparisons were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance, followed by Student-Newman-Keuls for pair-wise multiple comparisons, or the Kruskall-Wallis test, where appropriate. Physiological parameters were evaluated by repeated measures analysis of variance. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Physiological Responses Over Time

When indicated, rats received LPS intratracheally and/or a pretreatment with captopril (see Materials and Methods). Hereafter, the animals were ventilated with moderate pressure amplitudes (PIP 26/PEEP 5 cmH2O). Nonventilated animals served as controls.

Blood pressure of the captopril-pretreated and the LPS-exposed animals showed a significant reduction compared with nonpretreated/non-LPS exposed animals (Table 1). In the nonpretreated animals, mechanical ventilation resulted in a decrease in PaCO2 levels during the first hour (P < 0.05). pH values in LPS-exposed animals without captopril pretreatment increased initially and then decreased to original values, also within the first 2 hours (P < 0.05). Exposure to LPS and/or captopril did not have an effect on mean PaO2 levels.

Table 1.

Physiological Parameters

| Physiological parameters | Pre | 1 hour | 2 hours | 3 hours | 4 hours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure, mmHg | |||||

| Non-LPS without captopril | 129 ± 27 | 142 ± 13 | 135 ± 20 | 125 ± 12 | 120 ± 25 |

| Non-LPS with captopril | 111 ± 17 | 118 ± 16* | 107 ± 26* | 95 ± 24* | 96 ± 14 |

| LPS without captopril | 119 ± 17 | 114 ± 22* | 103 ± 26* | 101 ± 18* | 107 ± 14 |

| LPS with captopril | 130 ± 20 | 114 ± 22* | 111 ± 21* | 106 ± 23* | 99 ± 24 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | |||||

| Non-LPS without captopril | 29.28 ± 5.85 | 24.64 ± 4.61† | 26.60 ± 4.84‡ | 25.91 ± 5.62 | 25.30 ± 4.20 |

| Non-LPS with captopril | 28.61 ± 2.83 | 28.08 ± 4.30 | 28.34 ± 3.11 | 27.29 ± 3.02 | 26.13 ± 2.73 |

| LPS without captopril | 30.27 ± 3.20 | 23.31 ± 1.99† | 27.09 ± 4.96‡ | 28.92 ± 4.58 | 28.84 ± 3.67 |

| LPS with captopril | 27.02 ± 4.28 | 25.31 ± 4.26 | 27.21 ± 2.67 | 26.37 ± 3.16 | 25.59 ± 2.81 |

| pH | |||||

| Non-LPS without captopril | 7.48 ± 0.07 | 7.50 ± 0.05 | 7.49 ± 0.05 | 7.47 ± 0.06 | 7.45 ± 0.07 |

| Non-LPS with captopril | 7.47 ± 0.06 | 7.46 ± 0.04 | 7.46 ± 0.04 | 7.49 ± 0.04 | 7.47 ± 0.04 |

| LPS without captopril | 7.52 ± 0.05 | 7.59 ± 0.04† | 7.54 ± 0.04‡ | 7.53 ± 0.07 | 7.52 ± 0.05 |

| LPS with captopril | 7.56 ± 0.06 | 7.51 ± 0.07 | 7.47 ± 0.03 | 7.48 ± 0.07 | 7.45 ± 0.08 |

| PaO2, mmHg | |||||

| Non-LPS without captopril | 519.71 ± 62.02 | 532.31 ± 54.25 | 538.78 ± 36.71 | 536.79 ± 40.41 | 524.09 ± 42.21 |

| Non-LPS with captopril | 514.62 ± 25.95 | 525.21 ± 59.47 | 510.10 ± 34.52 | 529.79 ± 23.83 | 519.82 ± 40.47 |

| LPS without captopril | 540.43 ± 59.87 | 565.11 ± 82.84 | 531.50 ± 150.90 | 497.43 ± 165.48 | 486.60 ± 170.01 |

| LPS with captopril | 580.86 ± 62.17 | 553.98 ± 67.85 | 528.86 ± 55.18 | 533.38 ± 103.17 | 511.58 ± 108.89 |

Physiological parameters during mechanical ventilation of non-LPS and LPS-exposed animals ventilated at PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O, with or without pretreatment with captopril. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

P < 0.05, compared with non-LPS exposed animals without pretreatment with captopril.

P < 0.05, compared with time point “pre.”

P < 0.05, compared with time point “1 hour.”

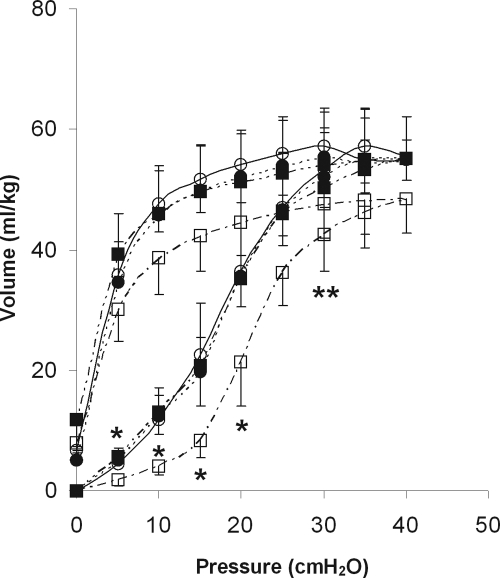

Figure 1 shows the P/V curves of the ventilated animals. LPS exposure resulted in a decrease of lung volumes on the inspiratory limb of the P/V curve after 4 hours of ventilation compared with the non-LPS exposed animals (Figure 1; P < 0.05). Pretreatment with captopril caused a significant reversal of this decrease.

Figure 1.

Static pressure-volume curves after 4 hours of mechanical ventilation of non-LPS exposed (circles) and LPS-exposed (squares) animals ventilated at PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O, with (black circles and squares) or without (white circles and squares) pretreatment with captopril. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. N = 9 per group. *P < 0.05, LPS-exposed animals without captopril pretreatment compared with all other groups. **P < 0.05, LPS-exposed animals without captopril pretreatment compared with non-LPS exposed animals with or without captopril.

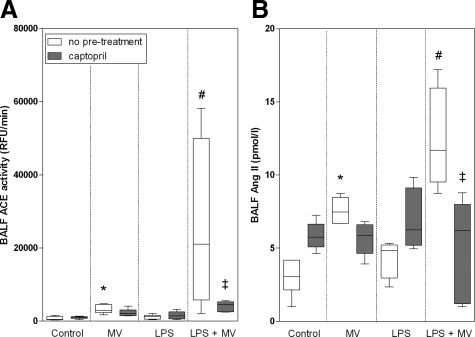

ACE Activity and Ang II

Whereas ventilation of animals without LPS-exposure increased BALF ACE activity compared with controls (P < 0.05; Figure 2A), intratracheal instillation of LPS in nonventilated animals did not result in increased BALF ACE activity. Interestingly, in ventilated rats exposed to LPS, there was an eightfold increase of BALF ACE activity compared with non-LPS exposed ventilated animals (P < 0.05; Figure 2A). In the ventilation group, pretreatment with captopril of animals exposed to LPS normalized ACE activity to the levels observed in ventilated animals without LPS exposure.

Figure 2.

Whisker plots of ACE activity (A) and Ang II levels (B) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of non-LPS, nonventilated (controls), only MV, only LPS-exposed, and LPS-exposed MV (LPS + MV) animals with or without pretreatment with captopril. Animals were ventilated at PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O. Data are expressed as median ± range. N = 6 per group. *P < 0.05, compared with nonventilated, non-LPS exposed animals (control); #P < 0.05, compared with nonventilated LPS-exposed (LPS only) and non-LPS exposed ventilated (MV only) animals; ‡P < 0.05 compared with ventilated LPS-exposed animals (LPS + MV) without captopril pretreatment.

BALF Ang II levels paralleled BALF ACE activity. Ang II levels were twofold higher in the non-LPS exposed ventilated animals compared with the nonventilated animals (P < 0.05; Figure 2B). Intratracheal instillation of LPS did not influence BALF Ang II levels in the nonventilated animals. However, compared with the non-LPS exposed animals, an additional twofold increase was observed when the LPS-exposed animals were ventilated (P < 0.05). This increase could be diminished by pretreatment with captopril (P < 0.05).

Protein Content and Inflammatory Mediators

Mechanical ventilation and/or intratracheal administration of LPS significantly increased BALF protein content (mean ± SD: 162 ± 63 μg/ml [MV], 183 ± 71 μg/ml [LPS], and 258 ± 111 μg/ml [LPS + MV] vs. 49 ± 25 μg/ml [control]). Pretreatment with captopril had no significant effect on BALF protein content in any of the experimental groups.

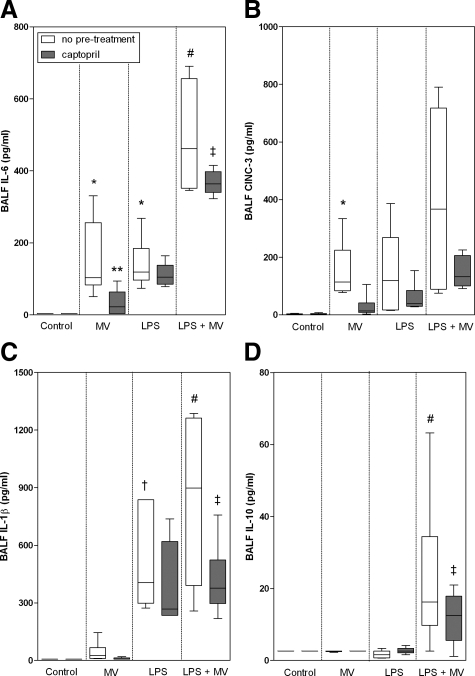

The levels of the inflammatory mediators interleukin-6, CINC-3, and interleukin-1β paralleled each other (Figure 3, A–C). Mechanical ventilation (interleukin-6 and CINC-3) and/or exposure to LPS (interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β) enhanced levels of the inflammatory mediators compared with non-LPS exposed, nonventilated animals (P < 0.05). Mechanical ventilation of LPS-exposed animals resulted in a further increase of all three mediator levels (P < 0.05 for interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β, CINC-3, not significant). Pretreatment with captopril caused a significant decrease of the mediator levels in both nonexposed (for interleukin-6) and LPS-exposed ventilated animals (interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β). Captopril pretreatment attenuated CINC-3 levels in the non-LPS exposed and LPS-exposed animals in a trend-wise manner, albeit the difference was not significant. Whereas BALF interleukin-10 levels were not detectable in either of the other groups, ventilation of LPS-exposed animals resulted in a marked increase of these levels (P < 0.05; Figure 3D). In this latter group, captopril pretreatment significantly reduced interleukin-10 levels.

Figure 3.

Whisker plots of levels of interleukin (IL)-6 (A), CINC-3 (B), IL-1β (C), and IL-10 (D) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of non-LPS, nonventilated (controls), only MV, only LPS-exposed, and LPS-exposed MV (LPS + MV) animals with or without pretreatment with captopril. Animals were ventilated at PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O. Data are expressed as median ± range. N = 6 per group. *P < 0.05, compared with non-LPS exposed nonventilated animals (control); **P < 0.05, compared with ventilated non-LPS exposed animals (MV only) without captopril pretreatment; #P < 0.05, compared with nonventilated LPS-exposed animals (LPS only) and ventilated non-LPS exposed animals (MV only); †P < 0.05, compared with non-LPS exposed, nonventilated (control) and ventilated (MV only) animals; ‡P < 0.05, compared with ventilated LPS-exposed animals (LPS + MV) without captopril pretreatment.

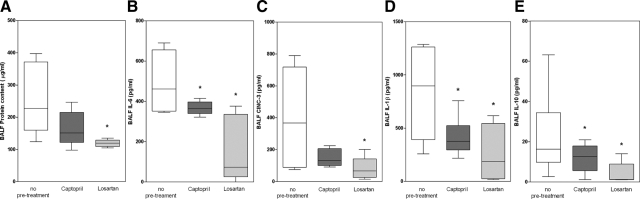

Contribution of Ang II

To further elucidate the contribution of Ang II to the exaggerated inflammatory mediator responses in LPS-exposed ventilated animals, its receptor antagonist Losartan was used (Figure 4). If the effects of ACE on inflammatory mediator production were mediated by Ang II, blocking the Ang II receptor would yield the same effect as blocking ACE with captopril. Indeed, blocking Ang II receptors with Losartan resulted in an even stronger effect of reduced BALF protein content (Figure 4A) and BALF inflammatory mediator levels (interleukin-6, CINC-3, interleukin-1β, and interleukin-10; Figure 4, B–E) in ventilated, LPS-exposed animals as observed after captopril pretreatment.

Figure 4.

Whisker plots of protein content (A), interleukin (IL)-6 (B), CINC-3 (C), IL-1β (D), and IL-10 (E) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of LPS-exposed animals ventilated at PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O without pretreatment or with pretreatment with captopril or Losartan. Data are expressed as median ± range. N = 6 per group. *P < 0.05, compared with no pretreatment.

Lung Injury Score and Immunohistochemistry

Histological evaluation of lung tissue from non-LPS exposed ventilated animals showed slightly increased injury when compared with nonventilated animals, albeit the difference was not significant (Table 2; Figure 5, A–H). In nonventilated animals LPS exposure resulted in significantly higher lung injury scores compared with healthy nonventilated and even healthy ventilated animals (Table 2; Figure 5). Ventilation of the LPS-exposed animals further increased lung injury scores, albeit the difference was not significant. Pretreatment with captopril had no significant effect on lung injury scores.

Table 2.

Lung Injury Scores

| Group | Congestion

|

Leukocytes

|

Thickness alveolar wall | Hemorrhage | Total injury score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-vascular | Alveolar | Peri-bronchial | Intravascular | ||||

| Control | |||||||

| Non-LPS without captopril pretreatment | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 2.6 |

| Non-LPS with captopril pretreatment | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 |

| LPS without captopril pretreatment | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 13.3 ± 2.3* |

| LPS with captopril pretreatment | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 16.5 ± 3.1* |

| Mechanical ventilation | |||||||

| Non-LPS without captopril pretreatment | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 6.3 ± 1.0 |

| Non-LPS with captopril pretreatment | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 0.5 |

| LPS without captopril pretreatment | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 18.0 ± 5.3* |

| LPS with captopril pretreatment | 3.0 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.3 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 16.7 ± 5.8* |

Lung injury scores of non-LPS and LPS-exposed animals ventilated at PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O, with or without pretreatment with captopril. Nonventilated animals served as controls. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

P < 0.05, compared with the non-LPS exposed animals with or without captopril.

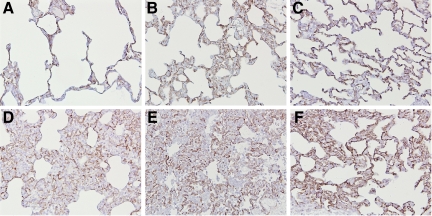

Figure 5.

H&E staining of lung tissue of non-LPS exposed, nonventilated (A and E) and MV (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O) animals (B and F), LPS-exposed nonventilated (C and G) and MV (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O) animals (D and H) without (A–D) or with (E–H) captopril pretreatment. Original magnification, ×20.

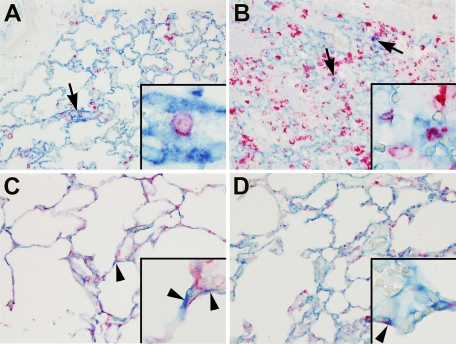

Immunohistochemical staining of ACE in lung tissue revealed positive staining of endothelial cells (Figure 6, A–F). However, also cells in the alveolar walls were ACE-positive. Double staining of the lung tissue showed that these ACE-positive cells are alveolar macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells (Figure 7, A–D). Neither mechanical ventilation nor LPS caused any changes in the localization and intensity of staining. Also, pretreatment with captopril had no influence on the number and nature of ACE-positive cells.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry for ACE in lung tissue of non-LPS exposed (A–C) or LPS-exposed (D–F) animals, which were either nonventilated (A and D) or MV (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O) without (B and E) or with (C and F) captopril pretreatment. Diffuse staining was found on endothelial cells and also on cells in the alveolar walls. Original magnification, ×20.

Figure 7.

Dual immunohistochemistry for ACE (developed by vector blue) and macrophage marker ED-1 (A and B) or epithelial cell marker AE1/AE3 (C and D; both developed by liquid permanent red) in lung tissue of non-LPS exposed (A and C) or LPS-exposed (B and D) animals, which were ventilated with moderate pressure amplitudes (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O). Co-staining showed ACE-positive alveolar macrophages (arrows and insets) and ACE-positive alveolar epithelial cells (arrowheads). Original magnification, ×20; insets, ×100.

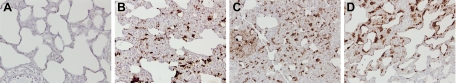

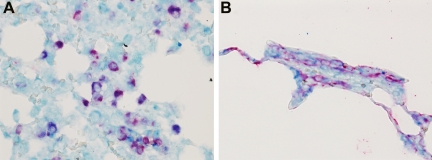

In the non-LPS exposed animals, AT1-positive cells were detected only with a high concentration AT1 antibody (1:50; data not shown). This result was irrespective of ventilation or captopril treatment. In contrast, after LPS exposure, AT1-positive cells were already found by using a 1:250 dilution of the antibody (Figure 8, A–D). Ventilation of LPS-exposed animals increased the surface area of AT1-staining in the tissue from 5% in nonventilated animals to 9.5% in the ventilated animals, albeit the difference was not significant. Pretreatment with captopril had no effect on the surface area of AT1-staining in LPS-exposed animals that were, or were not, mechanically ventilated. Double staining of the lung tissue showed that the AT1-positive cells are alveolar macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells (Figure 9, A and B).

Figure 8.

Immunohistochemistry for AT1 (antibody dilution 1:250) in lung tissue of non-LPS exposed animals ventilated with moderate pressure amplitudes (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O; A), nonventilated LPS-exposed animals (B), and LPS-exposed animals without (C) or with (D) captopril pretreatment ventilated with moderate pressure amplitudes (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O). AT1 positive cells (brown color) were found after intratracheal LPS instillation, with increasing surface area of AT1-positive cells after mechanical ventilation of these animals. Original magnification, ×20.

Figure 9.

Dual immunohistochemistry for AT1 (developed by vector blue) and macrophage marker ED-1 (A) or epithelial cell marker AE1/AE3 (B; both developed by liquid permanent red) in lung tissue of LPS-exposed animals, which were ventilated with moderate pressure amplitudes (PIP 26 cmH2O/PEEP 5 cmH2O). Co-staining showed AT1-positive alveolar macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells. Original magnification, ×40.

Discussion

In the present study, ventilation of preinjured (ie, LPS-exposed) lungs resulted in an exaggerated inflammatory mediator production via ACE-induced Ang II. The P/V loops, reflecting respiratory compliance and elastic properties, were attenuated in ventilated LPS-exposed lungs via ACE. This indicates that ACE mediates acute injury in LPS-exposed lungs. However, this was not corroborated by histological data.

Overall, these findings support the concept that modulation of the RAS may intervene with VILI in patients with ALI/ARDS, with or without pre-existing lung injury.

Ventilation of healthy animals results in an inflammatory response in the lung that is mediated by ACE via an increased production of its effector-peptide, Ang II.11,12 In the present study, ventilated LPS-exposed animals had markedly enhanced BALF Ang II levels and enhanced expression in the lungs of the Ang II receptor, AT1. BALF protein levels and inflammatory mediator production were reduced by the Ang II antagonist, Losartan, to a larger extent than after blocking ACE. Taken together, these results are highly suggestive of Ang II also being an intermediary in VILI of LPS-exposed lungs. In other models of ALI (ie, acid and sepsis-induced lung injury), it was shown that lung injury was also regulated by ACE via Ang II.10 Both ACE and AT1 receptor knockout mice showed reduced symptoms of ALI; it was concluded that ACE, via Ang II and its AT1 receptor, functions as a lung injury-promoting factor.10

It is unclear whether BALF ACE is derived from the airways and/or from the circulation. The localization of AT1 receptor on the alveolar epithelial cells and on macrophages suggests the presence of a local (pulmonary) RAS. This is strengthened by the fact that these cells are capable of producing RAS components in vitro19,20 and by our immunohistochemistry data that show that alveolar macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells contain ACE. However, it cannot be excluded that ACE in alveolar macrophages is acquired by uptake. Moreover, we did not find an increase in pulmonary ACE and AT1 receptor staining in the various experimental groups. This suggests that enhanced leakage of systemic ACE, rather than enhanced local ACE and AT1 protein levels, affect the regulation of the RAS system in the lung under these conditions. In situ hybridizations may provide final proof for a role of a local RAS.

Whereas blocking of ACE inhibited the amount of proinflammatory mediators and improved lung mechanics, no effect on lung injury scores was found. We have two explanations for the absence of an improved histopathology. Firstly, a relatively high amount of LPS was used that caused substantial lung injury by itself. This injury was not accompanied by an increase in BALF ACE activity. In fact, the effect of LPS may have overshadowed a possible effect of ACE inhibition. Secondly, samples for immunohistopathology were collected after 4 hours of mechanical ventilation only. Likely, the attenuated proinflammatory mediator production by ACE inhibition may result in a reduced lung injury at later time points. This explanation is supported by the studies of Wang et al21 and Hagiwara et al,22 who showed reduced lung injury scores 12 to 24 hours after the initial insult of the lung of rodents.

Differences in systemic blood pressure and the use of hyperoxia can potentiate lung injury during ventilation.23 In the present study, however, they are not expected to be confounding factors. Previous studies showed that hyperoxia did not affect BALF ACE activity, protein content, or levels of inflammatory parameters.11,24,25 It is also unlikely that the observed decrease of blood pressure after captopril pretreatment and/or LPS during ventilation accounts for the differences in inflammatory response. It was shown that a decrease in LPS-induced pulmonary neutrophil recruitment after ACE inhibition was not paralleled by changes in blood pressure. Furthermore, pretreatment with another antihypertensive agent (without affecting ACE activity) had no effect on neutrophil accumulation despite a similar effect on blood pressure as compared with the ACE inhibitor.26 It was also reported that correction of hypotension during high tidal volume ventilation did not change microvascular leak in the lung.27 In contrast, antitumor necrosis factor antibodies prevented lung permeability.28 Taken together, these data suggest that inflammatory, rather than hemodynamic, mechanisms are involved in VILI. Indeed, the present study has shown that pretreatment with captopril is associated with an attenuated inflammation despite lower blood pressure. Differences in arterial pH and PaCO2 may also be potential confounding factors because of the known injurious effect of hypocapnic alkalosis on ventilator-associated lung injury.29,30 In the present study, however, no differences were found in pH and PCO2 values between the experimental groups during mechanical ventilation. Therefore, the differences in inflammatory response in these groups cannot be attributed to high pH or to low PCO2 values.

The main conclusion of this study is that the exaggerated lung inflammatory response in ventilated LPS-exposed rats is driven by ACE via its key effector peptide Ang II. This finding may have important clinical implications. Therapeutic agents that block the production of Ang II (ACE inhibitors) or the effect of Ang II (Ang II receptor antagonists) might be used to prevent ventilator-induced injury imposed on a preinjured lung. These drugs would dampen the mediator response and improve dynamic lung function, thereby improving the prognosis of ALI/ARDS. It would be interesting to assess whether the application of captopril after mechanical ventilation and LPS exposure is just as effective as before the insults.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Roelie M. Wösten-van Asperen, M.D., Department of Pediatric Intensive Care, Emma Children’s Hospital/Academic Medical Center, Meibergdreef 9, 1100 DD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. E-mail: r.m.vanasperen@amc.uva.nl.

References

- Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1998;157:294–323. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9604014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: from barotrauma to biotrauma. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1998;110:482–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JA, Parsons PE, Matthay MA. Pathogenetic significance of biological markers of ventilator-associated lung injury in experimental and clinical studies. Chest. 2006;130:1906–1914. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, Gharib SA, Glenny RW, Martin TR, Liles WC. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced gene transcription and promotion of lung injury by mechanical ventilation. J Immunol. 2005;175:3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead TC, Zhang H, Mullen B, Slutsky AS. Effect of mechanical ventilation on cytokine response to intratracheal lipopolysaccharide. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:52–58. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanireddy S, Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, O'Mahony DS, Glenny RW, Martin TR, Liles WC. Mechanical ventilation induces inflammation, lung injury, and extra-pulmonary organ dysfunction in experimental pneumonia. Lab Invest. 2006;86:790–799. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama K, Ishizaka A, Nakamura M, Kubo H, Kotani T, Yamamoto S, Ogawa EN, Kajikawa O, Frevert CW, Kotake Y, Morisaki H, Koh H, Tasaka S, Martin TR, Takeda J. Enhancement of the endotoxin recognition pathway by ventilation with a large tidal volume in rabbits. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1114–L1121. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00296.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RP, Webb S, Bellingan GJ, Montgomery HE, Chaudhari B, McAnulty RJ, Humphries SE, Hill MR, Laurent GJ. Angiotensin converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism is associated with susceptibility and outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:646–650. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, Yang P, Sarao R, Wada T, Leong-Poi H, Crackower MA, Fukamizu A, Hui CC, Hein L, Uhlig S, Slutsky AS, Jiang C, Penniger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wösten-van Asperen RM, Lutter R, Haitsma JJ, Merkus MP, van Woensel JB, van der Loos CM, Florquin S, Lachmann B, Bos AP. ACE mediates ventilator-induced lung injury in rats via angiotensin II but not bradykinin. Eur Resp J. 2008;31:363–371. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00060207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerng JS, Hsu YC, Wu HD, Pan HZ, Wang HC, Shun CT, Yu CJ, Yang PC. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in ventilator-induced lung injury: an in vivo study in a rat model. Thorax. 2007;62:527–535. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.061945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteban V, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Suzuki Y, Mezzano S, Blanco J, Kretzler M, Sugaya T, Egido J, Ruiz-Ortega M. Angiotensin II, via AT1 and AT2 receptors and NF-kappa B pathway, regulates the inflammatory response in unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1514–1529. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130564.75008.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ortega M, Ruperez M, Lorenzo O, Esteban V, Blanco J, Mezzano S, Egido J. Angiotensin II regulates the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the kidney. Kidney Int Suppl. 2002;82:12–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.62.s82.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:881–900. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachmann B, Robertson B, Vogel J. In vivo lung lavage as an experimental model of the respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1980;24:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1980.tb01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Loos CM, Teeling P. A generally applicable sequential alkaline phosphatase immunohistochemical double staining. J Histotechnol. 2008;31:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson RM, Mansfield JR. Multispectral imaging in biology and medicine: slices of life. Cytometry. 2006;69:748–758. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Zagariya A, Ibarra-Sunga O, Gidea C, Ang E, Deshmukh D, Chaudhary G, Buraboutis J, Filippatos G, Uhal BD. Angiotensin II induces apoptosis in human and rat alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 1999;276:L885–L889. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhal BD, Kim JK, Li X, Molina-Molina M. Angiotensin-TGF-beta 1 crosstalk in human idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: autocrine mechanisms in myofibroblasts and macrophages. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1247–1256. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Xia ZF, Chen XL, Jia YT, Wang YJ, Ma B. Angiotensin II type-1 receptor antagonist attenuates LPS-induced acute lung injury. Cytokine. 2009;48:246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S, Iwasaka H, Matumoto S, Hidaka S, Noguchi T. Effects of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on the inflammatory response in in vivo and in vitro models. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:626–633. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181958d91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DA, Moufarrej RK, Volokhov A, Hules CA. Interactions of lung stretch, hyperoxia, and MIP-2 production in ventilator-induced lung injury. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:517–525. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00570.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair SE, Altemeier WA, Matute-Bello G, Chi EY. Augmented lung injury due to interaction between hyperoxia and mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2496–2501. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000148231.04642.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TC, Maruscak AA, Martin EL, Forbes AR, Petersen A, McCaig LA, Yao LJ, Lewis JF, Veldhuizen RA. The effects of long-term conventional mechanical ventilation on the lungs of adult rats. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2381–2387. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b65c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt PG, Young SK, Poch KR, Nick JA, Falk S, Schrier RW, Worthen GS. Systemic inhibition of the angiotensin-converting enzyme limits lipopolysaccharide-induced lung neutrophil recruitment through both bradykinin and angiotensin II-regulated pathways. J Immunol. 2006;177:7233–7241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guery BP, Welsh DA, Viget NB, Robriquet L, Fialdes P, Mason CM, Beaucaire G, Bagby GJ, Nevierre R. Ventilation-induced lung injury is associated with an increase in gut permeability. Shock. 2003;19:559–563. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000070738.34700.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WI, Quinn DA, Park KM, Moufarrej RK, Jafari B, Syrkina O, Bonventre JV, Hales C. Systemic microvascular leak in an in vivo rat model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1627–1632. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1216OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffey JG, Engelberts D, Duggan M, Veldhuizen R, Jewis JF, Kavanagh BP. Carbon dioxide attenuates pulmonary impairment resulting from hyperventilation. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2634–2640. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000089646.52395.BA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffey JG, Engelberts D, Kavanagh BP. Injurious effects of hypocapnic alkalosis in the isolated lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:399–405. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9911026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]