Abstract

Human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (IR) is a frequent phenomenon carrying high morbidity and mortality. Although intestinal IR-induced inflammation has been studied extensively in animal models, human intestinal IR induced inflammatory responses remain to be characterized. Using a newly developed human intestinal IR model, we show that human small intestinal ischemia results in massive leakage of intracellular components from ischemically damaged cells, as indicated by increased arteriovenous concentration differences of intestinal fatty acid binding protein and soluble cytokeratin 18. IR-induced intestinal barrier integrity loss resulted in free exposure of the gut basal membrane (collagen IV staining) to intraluminal contents, which was accompanied by increased arteriovenous concentration differences of endotoxin. Western blot for complement activation product C3c and immunohistochemistry for activated C3 revealed complement activation after IR. In addition, intestinal IR resulted in enhanced tissue mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, which was accompanied by IL-6 and IL-8 release into the circulation. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 was markedly increased during reperfusion, facilitating influx of neutrophils into IR-damaged villus tips. In conclusion, this study for the first time shows the sequelae of human intestinal IR-induced inflammation, which is characterized by complement activation, production and release of cytokines into the circulation, endothelial activation, and neutrophil influx into IR-damaged tissue.

Intestinal ischemia-reperfusion (IR) is a frequently occurring phenomenon during abdominal and thoracic vascular surgery, small bowel transplantation, hemorrhagic shock, and surgery using cardiopulmonary bypass, carrying high morbidity and mortality.1,2,3,4,5 Intestinal IR is associated with intestinal barrier function loss, which facilitates bacterial translocation into the circulation, thereby triggering systemic inflammation.6,7 Moreover, reperfusion of ischemically damaged intestinal tissue further aggravates tissue damage and is considered to be an effector of local as well as distant inflammation and multiple organ failure,2,5 which remains the leading cause of death in critically ill patients.8

Recently our group developed an experimental human model that enables us to study the consequences of human small intestinal IR, in which it was observed that the human gut is remarkably resistant to short ischemic periods. After 30 minutes of jejunal ischemia the epithelial lining remained intact and reperfusion-induced intestinal damage was rapidly restored, thereby preventing inflammation.9,10 Interestingly, these data were in contrast with animal studies, in which intestinal IR has been shown to elicit an inflammatory response.3,11,12,13 These studies revealed that intestinal IR-induced inflammation is characterized by the production of cytokines (including interleukin [IL]−6),14,15 and sequestration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) into ischemically damaged tissue. Migration of PMNs is facilitated by endothelial expression of adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).16,17 In addition, the complement system is considered an important mediator of innate immune defense after intestinal IR and has been shown to contribute to the attraction of neutrophils to ischemically damaged tissue.12,17,18,19 By locally releasing myeloperoxidase (MPO) and other proinflammatory mediators, PMNs contribute substantially to IR-induced tissue damage.20,21,22 Apart from local tissue damage and inflammation, a systemic inflammatory response can also be triggered by translocation of proinflammatory compounds such as endotoxin from the gut lumen through a compromised intestinal barrier.8,23,24,25

The current study reveals for the first time the sequelae of human small intestinal IR-induced inflammation. First, we show that prolonged human jejunal ischemia (45 minutes), followed by reperfusion, results in intestinal barrier integrity loss, which is accompanied by significant translocation of endotoxin. Second, we demonstrate that these phenomena result in an inflammatory response characterized by complement activation, endothelial activation, neutrophil sequestration, and release of proinflammatory mediators into the circulation.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Maastricht University Medical Center and written informed consent of all patients was obtained.

Patients and Surgical Procedures

The experimental protocol was performed as previously described.9 In short, 10 patients (6M:4F) with a median age of 66 years (range, 54 to 83 years) undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for benign or malignant disease were included in this study. Patients with bile-duct obstructive disease were stented before surgery. All patients had normal bile flow at the time of the surgical procedure. During pancreaticoduodenectomy, a variable segment of jejunum is routinely resected in continuity with the head of the pancreas and duodenum as part of the surgical procedure. The terminal 6 cm of this jejunal segment was isolated and subjected to 45 minutes of ischemia by placing two atraumatic vascular clamps over the mesentery. Meanwhile, surgery proceeded as planned. After 45 minutes of ischemia, one third (2 cm) of the isolated ischemic jejunum was resected using a linear cutting stapler. Next, clamps were removed to allow reperfusion, as confirmed by regaining of normal pink color and restoration of gut motility. Another segment of the isolated jejunum (2 cm) was resected similarly after 30 minutes of reperfusion. The last part was resected after 120 minutes of reperfusion. Simultaneously, 2 cm of jejunum, which remained untreated during surgery, was resected, serving as internal control tissue. This segment underwent similar surgical handling as the isolated part of jejunum, but was not exposed to IR. Tissue samples were immediately snap-frozen (Western blot, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction [qPCR], immunofluorescence on frozen sections) or formalin-fixed (immunohistochemistry). Jejunal samples collected after 120 minutes of reperfusion were filled with luminal debris, which was collected separately and immediately snap-frozen.

Blood Sampling

Arterial blood was sampled before ischemia, immediately on reperfusion, and at 30 and 120 minutes after start of reperfusion. Simultaneous with each respective arterial blood sample, blood was drawn from the venule draining the isolated jejunal segment by direct puncture to assess concentration gradients across the isolated jejunal segment. All blood samples were directly transferred to prechilled EDTA vacuum tubes (Becton Dickinson Diagnostics, Aalst, Belgium) and kept on ice. At the end of the procedure all blood samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm, 4°C for 15 minutes to obtain plasma. Plasma was immediately stored in aliquots at −80°C until analysis.

Histology

Tissue specimens obtained during the experimental protocol were immediately immersed in 4% formaldehyde fixative (Unifix, Klinipath, Duiven, the Netherlands) and incubated overnight at room temperature. Next, tissue samples were embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were cut. For morphological analysis, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol to distilled water and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunohistochemistry

After deparaffinization and rehydration of paraffin-embedded sections, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 0.6% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 minutes. Sections undergoing heat-mediated antigen retrieval (collagen IV and M30 staining) were heated in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes at 90°C. After blocking nonspecific antibody binding using 5% bovine serum albumin in PBS, sections were incubated with specific primary antibody at room temperature for 60 minutes. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-cleaved cytokeratin 18 antibody, clone M30 (Peviva, Bromma, Sweden), mouse anti-human ICAM-1 (monoclonal antibody HM2), rabbit anti-human MPO (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), mouse anti-human neutrophil defensin 1–3 (HNP 1–3, Hycult Biotechnology, Uden, the Netherlands), mouse anti-collagen IV (DakoCytomation), and mouse anti-human activated C3 (HM2168, Hycult Biotechnology). After washing, appropriate peroxidase-conjugated or biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies were used, the latter followed by incubation with the streptavidin-biotin system (DakoCytomation). Binding of primary antibody was visualized with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. Stained sections were photographed by a Nikon eclipse E800 microscope with a Nikon digital camera DXM1200F. No significant staining was detected in sections incubated with isotype control instead of the primary antibody. Neutrophil influx after IR was quantified in a blinded way by two observers by counting MPO-positive cells in five representative microscopic fields (×100) of stained control tissue and tissue exposed to IR.

Immunofluorescence

Cryostat sections (4 μm) were cut and stained for Zonula Occludens-1 (ZO-1). Briefly, slides were dried, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, and nonspecific antibody binding was blocked using 10% normal goat serum. Next, slides were incubated with rabbit anti-human ZO-1 (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA). After washing, slides were incubated with a Texas Red–labeled secondary antibody (Jackson, West-Grove, PA), followed by incubation with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenyl indole (DAPI). Next, slides were dehydrated in ascending ethanol series, mounted in fluorescence mounting solution (Dakocytomation), and visualized with an immunofluorescence microscope.

RNA and Protein Isolation

RNA and protein was isolated using AllPrep DNA/RNA/Protein kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In short, jejunal samples were crushed with a pestle and mortar in liquid nitrogen. Disruption and homogenization of the tissue was performed using an Ultra Turrax Homogenizer (IKA Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany) in lysis buffer containing β-Mercaptoethanol (Promega, Madison, WI). RNeasy spin columns were used to bind RNA; proteins in the flow-through were precipitated. Columns were washed and RNA was eluted in RNase-free water. Protein precipitate was centrifuged, washed, and the pellet was dissolved in 5% SDS. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Real-Time qPCR

To analyze gene expression of IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, qPCR was performed using individual cDNA samples. RNA samples were treated with DNase (Promega) to ensure removal of contaminating genomic DNA. RNA quantity was measured using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Witec AG, Heitersheim, Germany). Total cDNA was synthesized with oligo(dT) primers, dNTPs, and Molony murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Eurogentec, Liège, Belgium). qPCR reactions were performed in a volume of 20 μl containing 10 ng of cDNA, 1× IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and 300 nmol/L of gene-specific forward and reverse primers for IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α. Sequence of primers is provided in Table 1. cDNA was amplified using a three-step program (40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 20 s at 60°C, and 20 s at 70°C) with a MyiQ system (Bio-Rad). Specificity of amplification was verified by melt curve analysis. Gene expression levels were determined using iQ5 software using a ΔCt relative quantification model. The geometric mean of two internal control genes, RPLP-0 and Cyclophylin A, was calculated and used as a normalization factor. Control intestinal specimens, not subjected to IR, were collected after the IR procedure to rule out possible confounding increased production of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α induced by intestinal manipulation during the surgical procedure, which has been described previously.26

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide Primer Sequences Used for qPCR

| Gene | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 5′-TCCAGGAGCCCAGCTATGAA-3′ | 5′-GAGCAGCCCCAGGGAGAA-3′ |

| IL-8 | 5′-CTGGGCGTGGCTCTCTTG-3′ | 5′-TTAGCACTCCTTGGCAAAACTC-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-TCAATCGGCCCGACTATCTC-3′ | 5′-CAGGGCAATGATCCCAAAGT-3′ |

| RPLP-0 | 5′-GCAATGTTGCCAGTGTCTG-3′ | 5′-GCCTTGACCTTTTCAGCAA-3′ |

| Cycophilin A | 5′-CTCGAATAAGTTTGACTTGTGTTT-3′ | 5′-CTAGGCATGGGAGGGAACA-3′ |

Western Blot Analysis

Protein concentrations of samples were determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Etten-Leur, the Netherlands). Equal amounts of total protein (10 μg) were heated in a SDS sample buffer containing β-Mercaptoethanol and loaded on an 8% SDS polyacrylamide gel. Gels were blotted on a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (ImmobiliP, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were blocked in 5% bovine serum albumin and incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-human C3c (DakoCytomation). After washing, membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson). To ensure equal loading and transfer, membranes were reprobed with mouse anti-human β-actin (Sigma) and rat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated antibody (Jackson) was used as secondary antibody. Signals were captured on X-ray film (Fuji, SuperRX, Tokyo, Japan) by chemiluminescence using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce).

Plasma Measurements

All parameters were determined in both arterial plasma samples and plasma derived from the vein directly draining the studied jejunum, to allow for calculation of arteriovenous concentration differences.

Intestinal Fatty Acid Binding Protein

Intestinal fatty acid binding protein (I-FABP) is a small (14-kD) cytosolic protein specifically present in mature enterocytes of the gut. Plasma I-FABP concentrations were measured by means of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Hycult Biotechnology).

M65 and M30

M65 and M30 concentrations, reflecting overall epithelial cell death and apoptosis, respectively, were measured in plasma using ELISA (M65 ELISA and M30 apoptosense ELISA, Peviva). The M65 ELISA measures soluble cytokeratin 18, a 45-kDa protein abundantly present in epithelial cells. Soluble cytokeratin 18 is released from dying cells as a result of enterocyte membrane integrity loss. The M30-apoptosense ELISA is based on the M30 monoclonal antibody, which specifically recognizes a neo-epitope formed after cleavage of cytokeratin 18, a process specifically occurring during apoptosis of cytokeratin 18 containing cells.

Endotoxin

Plasma endotoxin levels were measured using the highly sensitive limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (Hycult Biotechnology). Increase of arteriovenous endotoxin concentration differences compared with baseline levels was determined to specifically evaluate barrier function loss as a consequence of intestinal IR.

IL-6 and IL-8

Plasma IL-6 and IL-8 levels were measured using ELISA. The IL-6 and IL-8 ELISA was performed as previously described.27

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 4.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Bonferroni or Dunn multiple comparison test was used (after significant one-way analysis of variance) to compare values in time. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. A P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Intestinal IR Results in Loss of Intestinal Barrier Integrity and Leakage of Intracellular Components from Damaged Enterocytes

Directly after ischemia, disintegration of the intestinal epithelial lining and appearance of subepithelial spaces was observed (Figure 1B). During reperfusion, ischemically damaged enterocytes on the tips of the villi were shed into the intestinal lumen, resulting in further disintegration of intestinal barrier integrity (Figure 1C and supplemental Figure S1A, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The epithelial lining was not restored on 120 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 1D). Local loss of the epithelial lining led to exposure of intraluminal compounds to the basal membrane, directly after ischemia (Figure 1F) as well as during 30 and 120 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 1, G and H, respectively, and supplemental Figure S1B, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), which was demonstrated using immunohistochemistry for collagen IV, a major constituent of the gut basal membrane. Enterocyte damage was quantified by measuring arteriovenous I-FABP concentration differences across the studied jejunum. I-FABP arteriovenous concentration differences significantly increased from 0.29 ng/ml before ischemia to 25.97 ng/ml on reperfusion (P < 0.001), indicating loss of enterocyte membrane integrity during the ischemic phase (Figure 2A, left). Additional evidence for leakage of intracellular components from dying cells was obtained by measuring M65 concentration differences over the studied jejunum, revealing a significant increase of M65 release directly after ischemia (Figure 2A, middle: 14.71 U/ml before ischemia to 584.5 U/ml on reperfusion; P < 0.01). Both I-FABP and M65 levels gradually decreased during the reperfusion phase (Figure 2A, left and middle, respectively).

Figure 1.

Intestinal IR-induced epithelial lining breakdown resulting in exposure of the basal membrane to intraluminal content. Hematoxylin and eosin staining (×200) shows an intact villus structure in control tissue (A), whereas 45I led to disruption of the epithelial lining (arrowheads) and appearance of subepithelial spaces (arrows) (B). After 45I-30R, damaged enterocytes were shed into the lumen (C). The epithelial lining remained compromised after 45I-120R (D). Collagen IV staining (red) revealed that enterocytes were attached to the basal membrane in control tissue (E). Destruction of the epithelial lining after 45I and 45I-30R resulted in exposure of the basal membrane to intraluminal contents (F and G respectively, arrows), which was not fully reversed after 45I-120R (H).

Figure 2.

Intestinal IR results in apoptosis and massive leakage of intracellular components from IR-damaged enterocytes. A: I-FABP arteriovenous concentration differences increased on reperfusion (***P < 0.001), reflecting enterocyte membrane integrity loss. This was accompanied by leakage of M65 from dying cells (**P < 0.01). Both I-FABP and M65 levels decreased over the course of reperfusion. Arteriovenous concentration differences of M30 did not change over time. B: Immunohistochemistry for M30 showed that apoptosis was sporadically present in villus tips of healthy jejunum and jejunum exposed to ischemia alone (left and right upper, respectively). M30 positivity was mainly observed in detaching enterocytes at 30 minutes of reperfusion (left lower) and in the luminal debris of IR-damaged cells at 120 minutes of reperfusion (right lower).

Immunohistochemical analysis of M30, reflecting apoptosis-specific cytokeratin 18 caspase-cleavage, showed that apoptosis was not induced by ischemia alone (Figure 2B, upper right). In line with this observation, M30 arteriovenous concentration differences remained low directly after ischemia (Figure 2A, right). Apoptosis was only observed at the tips of the detaching villi during early reperfusion and in the luminal debris at a later stage (Figure 2B, left lower and right lower, respectively), likely explaining the absence of M30 arteriovenous concentration differences during reperfusion.

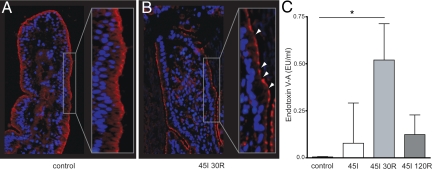

Intestinal IR-Induced Tight Junction Loss and Loss of Intestinal Barrier Function

Analysis of the distribution of tight junction protein ZO-1 revealed continuous ZO-1 staining in control tissue (Figure 3A), whereas loss of ZO-1 staining was observed in tissue exposed to IR, indicating tight junction loss (Figure 3B). To assess the functional consequences of the observed intestinal barrier integrity loss, translocation of endotoxin from the intestinal lumen into the circulation was measured. A significant increase in arteriovenous concentration differences of plasma endotoxin compared with baseline levels (before ischemia) was detected after 45 minutes of ischemia with 30 minutes reperfusion (P < 0.05), indicating impaired epithelial barrier function (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Intestinal IR-induced tight junction loss results in translocation of endotoxin to the circulation. Immunofluorescence for ZO-1 shows continuous staining in control jejunal tissue (A), whereas an interrupted staining pattern was observed over the villus lining after 45 minutes of ischemia with 30 minutes reperfusion (arrowheads), indicating tight junction loss (B). C: Significant translocation of endotoxin into the circulation was observed at 45 minutes of ischemia with 30 minutes of reperfusion (*P < 0.05).

Activation of the Complement System in Response to Intestinal IR

To investigate complement activation as a result of intestinal IR, tissue homogenates and homogenates of intraluminal cellular debris were analyzed for the presence of complement components C3c and native C3 using Western blot. Interestingly, high amounts of the complement activation product C3c, detected as a degraded α-chain of 40 kD,28 were detected in the luminal debris of ischemically damaged shedded enterocytes (Figure 4A, P < 0.001). In contrast, C3c was minimally present in control tissue and jejunal tissue exposed to ischemia alone, or jejunal tissue exposed to ischemia with 30 or 120 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 4A, IR represents 45I-120R; 45I and 45I-30R showed similar results, data not shown). In line with this, native C3, detected as a full α-chain of 113 kD,28 was present in tissue homogenates of control jejunal samples and IR-exposed jejunal tissue, whereas it was hardly detectable in the luminal debris (Figure 4B, P < 0.01). Activation of C3 was confirmed by immunohistochemistry, revealing activated C3 in the luminal debris of samples subjected to 45 minutes of ischemia with 30 minutes of reperfusion (data not shown) and 120 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Activation of the complement system in response to intestinal IR. A: Western blot analysis revealed that C3c, a product of C3 activation, was abundantly present in the luminal debris of shedded cells, whereas low C3c levels were observed in tissue homogenates of normal and IR-exposed jejunum (AU = arbitrary units, ***P < 0.001) B: In contrast, native C3 (113-kD bands) was present in both normal jejunum and jejunum exposed to IR, whereas it was hardly detected in luminal debris of IR-damaged, shedded cells. (AU indicates arbitrary units, **P < 0.01) C: Immunohistochemistry revealed the presence of activated C3 in luminal debris after 45 minutes of ischemia with 120 minutes of reperfusion.

Enhanced Expression of Endothelial Adhesion Molecules and Neutrophil Sequestration

ICAM-1 expression, as analyzed by immunohistochemistry, increased significantly on endothelial cells of ischemically damaged villi from hardly detectable before and directly after ischemia to a widespread expression during reperfusion, indicating endothelial activation (Figure 5A, upper and supplemental Figure S2A, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Expression of ICAM-1 was most prominent at 30 minutes of reperfusion in the most affected areas (i.e., the tips of the villi). Endothelial activation was accompanied by neutrophil sequestration into IR-damaged tissue as assessed by immunohistochemistry for MPO. Specificity of staining for neutrophils was verified with immunohistochemistry for human neutrophil defensin 1–3 (HNP 1–3), a protein specifically present in human neutrophils, which showed a similar staining pattern (data not shown). MPO staining showed increased numbers of neutrophils at 30 and 120 minutes of reperfusion on the tips of the villi, where tissue damage was most prominent (Figure 5A, lower, and supplemental Figure S2B, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Quantification of the amount of MPO-positive cells/villus demonstrated that neutrophil influx was significantly increased at 30 and 120 minutes of reperfusion when compared with control tissue (Figure 5B, P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively).

Figure 5.

Endothelial activation and influx of neutrophils into IR-damaged intestinal tissue. A: ICAM-1 staining reveals endothelial activation after 45 minutes of ischemia with 30 and 120 minutes of reperfusion, which was accompanied by influx of neutrophils into IR-damaged villus tips, as shown by MPO staining. B: The number of MPO-positive cells was significantly increased in IR-damaged villi after 30 and 120 minutes of reperfusion (***P < 0.001 and *P < 0.05, respectively).

Intestinal IR Results in Increased Tissue Cytokine mRNA Expression and Cytokine Release into the Circulation

Simultaneous with ICAM-1 increase and neutrophil influx, tissue mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α significantly increased during reperfusion (Figure 6, A–C, P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively). IL-6 was rapidly released into the circulation, resulting in significantly increased IL-6 arteriovenous concentration differences after 45 minutes ischemia with 30 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 6, P < 0.01). Both IL-6 and IL-8 arteriovenous concentration differences reached highest levels at 120 minutes of reperfusion (Figure 6, P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively).

Figure 6.

Intestinal IR results in increased IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α mRNA tissue expression, which is accompanied by release of IL-6 and IL-8 into the circulation. IL-6 (A) and IL-8 (B) mRNA expression and protein release into the circulation increased significantly during reperfusion of the ischemically damaged jejunal segment. In addition, intestinal IR resulted in increased mRNA expression of TNF-α (C). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

This study provides new insight into human intestinal IR- induced inflammation. We show that 45 minutes of small intestinal ischemia with reperfusion results in early loss of intestinal barrier integrity and failure to rapidly restore IR-induced damage to the epithelial lining. Importantly, loss of intestinal barrier integrity and extended exposure of cellular debris and intraluminal pathogens to the denuded basal membrane was accompanied by an inflammatory response. Human intestinal IR-induced inflammation was characterized by activation of the complement system, production and release of interleukins into the circulation, increased expression of endothelial adhesion molecules, and neutrophil sequestration into IR-damaged villi. These findings are in sharp contrast with previous work from our group, which showed that after short intestinal ischemia (30 minutes), the epithelial lining remained intact, and reperfusion-induced intestinal damage was restored within 120 minutes of reperfusion, thereby preventing vigorous inflammation.9,10 Here, we reveal that this previously observed ability of the human small intestine to prevent intestinal IR-induced inflammation is abolished by exposure to prolonged ischemia.

Two major pathophysiological mechanisms could account for activation of the innate immune system and the observed inflammatory response. First, intracellular components leaking from dying cells (damage-associated molecular patterns [DAMPs]) can trigger innate immune responses. Second, infiltrating microbiota and their products are potential effectors of the inflammatory response (pathogen-associated molecular patterns [PAMPs]). Both DAMPs and PAMPs interact with transmembrane and intracellular pattern recognition receptors, resulting in proinflammatory signaling.29,30 Here, we show that the epithelial enterocyte lining was destructed as a result of prolonged ischemia. The compromised enterocyte membrane integrity resulted in leakage of intracellular components, including I-FABP and soluble cytokeratin 18, from ischemically damaged enterocytes. We further show that after 45 minutes of ischemia, in contrast to 30 minutes of ischemia,9 interaction of cellular debris with lamina propria immune cells was facilitated by early loss of intestinal epithelial lining integrity and failure to rapidly restore IR-induced damage. Animal as well as in vitro studies have shown that such an interaction of cytoplasmic and nuclear components, released from dying cells, with innate immune cells results in massive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6.11,31,32

Apart from necrotic cell death, immunohistochemistry for M30 revealed that apoptotic cell death occurred particularly during reperfusion, which is consistent with previous studies on intestinal IR.9,33 Interestingly, however, M30 arteriovenous concentration differences remained low during reperfusion, suggesting that M30 remained within the apoptotic bodies and was not released into the circulation. In addition, leaking M30 (from apoptotically dying enterocytes undergoing secondary necrosis) was minimally exposed to lamina propria vasculature, because M30-positive cells were mainly detected in the detached enterocytes, thereby limiting release into the circulation.

In addition to the exposure to DAMPs, prolonged and extended loss of intestinal barrier integrity led to exposure of the basal membrane to intraluminal pathogens. Significantly increased arteriovenous concentration differences of strongly proinflammatory endotoxin reflected the destruction of the epithelial lining and tight junction loss, which was most prominent during reperfusion. This interaction of PAMPs with pattern recognition receptors is regarded a potent effector of the innate immune response during IR injury.29 Taken together, massive epithelial cell damage with leakage of intracellular components from dying cells and failure to restore IR-induced intestinal barrier integrity loss, leading to exposure to intraluminal pathogens, make DAMPs and PAMPs plausible initiators of inflammation after prolonged human intestinal IR.

The inflammatory response to intestinal IR has mainly been studied in murine models. Using these models, complement activation has been identified as a key mediator of postischemic damage.18 Involvement of the classical,34 the alternative,35,36 as well as the lectin12 activation pathway has been observed after intestinal IR. Central in the complement activation cascade is the activation of C3. Here, we show for the first time involvement of the complement system in human intestinal IR. Activated C3 was observed in the luminal debris but was absent in IR-damaged jejunal samples, suggesting that activation of C3 is triggered by IR-damaged detached enterocytes. Complement activation fragments as C3a have chemoattractant properties by itself, but have also been reported to induce production of other CXC-chemokines and cytokines.37 Hence, complement activation is likely one of the mechanisms accounting for the observed increased tissue mRNA expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α. In addition to the production and release of cytokines and chemokines, upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules3,38,39 and PMN adhesion and activation play important roles in the onset of inflammation after IR in animal models.17,18 In line with animal data, endothelial activation after human intestinal IR was observed as early as 30 minutes after the start of reperfusion. ICAM-1 expression was markedly increased at the tips of the villi (the locus of massive cell damage). This was accompanied by influx of neutrophils into the tips of IR-damaged jejunal villi, which is required to resolve local tissue damage and potential bacterial penetration. However, excessive neutrophil recruitment is also known to aggravate tissue damage and inflammation.16,20

The knowledge on complement activation, endothelial activation, and neutrophil influx after human intestinal IR, as observed in this study, offers opportunities for the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies to reduce intestinal IR-associated complications. Animal studies have already revealed beneficial effects of selective inhibitors and antagonists of the complement system in reducing local and remote tissue injury after intestinal IR.17,40 In addition, selective inhibitors of alpha4 leukocyte interaction with endothelial ligands on the gut microvasculature have proven to attenuate intestinal mucosal lesions.41

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that prolonged human intestinal IR results in extended loss of intestinal barrier integrity with exposure to both intraluminal pathogens and intracellular components leaking from IR-damaged enterocytes. The subsequent inflammatory response is characterized by complement activation, endothelial activation, and neutrophil sequestration. These data allow future translational studies to investigate targeted therapy to reduce intestinal IR-associated high morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

We thank the surgical team of the Maastricht University Medical Center for their excellent surgical assistance and Dr. Sander Rensen for critical revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Kaatje Lenaerts, Ph.D., Department of Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Center, PO Box 616, 6200 MD, Maastricht, the Netherlands. E-mail: kaatje.lenaerts@ah.unimaas.nl.

Supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development ZonMw (AGIKO-stipendium 920-03-438, to J.P.M.D.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement: guidelines on intestinal ischemia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:951–953. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lui VC, Rooijen NV, Tam PK. Depletion of intestinal resident macrophages prevents ischaemia reperfusion injury in gut. Gut. 2004;53:1772–1780. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.034868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blikslager AT, Moeser AJ, Gookin JL, Jones SL, Odle J. Restoration of barrier function in injured intestinal mucosa. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:545–564. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubes P, Hunter J, Granger DN. Ischemia/reperfusion-induced feline intestinal dysfunction: importance of granulocyte recruitment. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:807–812. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90010-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer-Vanniasinkam S, Crinnion JN, Gough MJ. Post-ischaemic organ dysfunction: a review. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997;14:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(97)80191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collard CD, Gelman S. Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and prevention of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:1133–1138. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200106000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink MP, Delude RL. Epithelial barrier dysfunction: a unifying theme to explain the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction at the cellular level. Crit Care Clin. 2005;21:177–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baue AE. MOF, MODS, and SIRS: what is in a name or an acronym? Shock. 2006;26:438–449. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000228172.32587.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derikx JP, Matthijsen RA, de Bruine AP, van Bijnen AA, Heineman E, van Dam RM, Dejong CH, Buurman WA. Rapid reversal of human intestinal ischemia-reperfusion induced damage by shedding of injured enterocytes and reepithelialisation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthijsen RA, Derikx JP, Kuipers D, van Dam RM, Dejong CH, Buurman WA. Enterocyte shedding and epithelial lining repair following ischemia of the human small intestine attenuate inflammation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LW, Egan L, Li ZW, Greten FR, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. The two faces of IKK and NF-kappaB inhibition: prevention of systemic inflammation but increased local injury following intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Nat Med. 2003;9:575–581. doi: 10.1038/nm849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart ML, Ceonzo KA, Shaffer LA, Takahashi K, Rother RP, Reenstra WR, Buras JA, Stahl GL. Gastrointestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury is lectin complement pathway dependent without involving C1q. J Immunol. 2005;174:6373–6380. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panes J, Granger DN. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions: molecular mechanisms and implications in gastrointestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1066–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daemen MA, van de Ven MW, Heineman E, Buurman WA. Involvement of endogenous interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation. 1999;67:792–800. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199903270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada M, Nadeau KC, Shaw GD, Marquette KA, Tilney NL. The cytokine-adhesion molecule cascade in ischemia/reperfusion injury of the rat kidney. Inhibition by a soluble P-selectin ligand. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2682–2690. doi: 10.1172/JCI119457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Montalto MC, Stahl GL. Inhibition of complement C5 reduces local and remote organ injury after intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:126–133. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Shiels IA, Woodruff TM, Granger DN, Taylor SM. The role of the complement system in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock. 2004;21:401–409. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming SD, Mastellos D, Karpel-Massler G, Shea-Donohue T, Lambris JD, Tsokos GC. C5a causes limited, polymorphonuclear cell-independent, mesenteric ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury. Clin Immunol. 2003;108:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi BR. Modulation of leukocyte-mediated myocardial reperfusion injury. Annu Rev Physiol. 1990;52:561–576. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg MH, Poch B, Younes M, Schwarz A, Baczako K, Lundberg C, Haglund U, Beger HG. Involvement of neutrophils in postischaemic damage to the small intestine. Gut. 1991;32:905–912. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.8.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthijsen RA, Huugen D, Hoebers NT, de Vries B, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, Aratani Y, Daha MR, Tervaert JW, Buurman WA, Heeringa P. Myeloperoxidase is critically involved in the induction of organ damage after renal ischemia reperfusion. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1743–1752. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnage RH, Guice KS, Oldham KT. The effects of hypovolemia on multiple organ injury following intestinal reperfusion. Shock. 1994;1:408–412. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukatsu K, Sakamoto S, Hara E, Ueno C, Maeshima Y, Matsumoto I, Mochizuki H, Hiraide H. Gut ischemia-reperfusion affects gut mucosal immunity: a possible mechanism for infectious complications after severe surgical insults. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:182–187. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000196207.86570.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotz MR, Deitch EA, Ding J, Xu D, Huang Q, Regel G. Intestinal cytokine response after gut ischemia: role of gut barrier failure. Ann Surg. 1999;229:478–486. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199904000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The FO, Bennink RJ, Ankum WM, Buist MR, Busch OR, Gouma DJ, van der Heide S, van den Wijngaard RM, de Jonge WJ, Boeckxstaens GE. Intestinal handling-induced mast cell activation and inflammation in human postoperative ileus. Gut. 2008;57:33–40. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.120238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen SJ, Derikx JP, Vermeulen Windsant IC, Heijmans JH, Koeppel TA, Schurink GW, Buurman WA, Jacobs MJ. Visceral injury and systemic inflammation in patients undergoing extracorporeal circulation during aortic surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;248:117–125. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181784cc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen SB, Thiel S, Teisner B, Holmskov U, Wang Y, Sim RB, Jensenius JC. Bovine conglutinin binds to an oligosaccharide determinant presented by iC3b, but not by C3, C3b or C3c. Immunology. 1994;81:648–654. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Okun E, Tang SC, Thundyil J, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. Toll-like receptors in ischemia-reperfusion injury. Shock. 2009;32:4–16. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318193e333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta MC, Bistritz L, Meddings JB. Alterations in intestinal permeability. Gut. 2006;55:1512–1520. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Tang J, Zheng P, Liu Y. CD24 and Siglec-10 selectively repress tissue damage-induced immune responses. Science. 2009;323:1722–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1168988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S, Ishikawa E, Sakuma M, Hara H, Ogata K, Saito T. Mincle is an ITAM-coupled activating receptor that senses damaged cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1179–1188. doi: 10.1038/ni.1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H, Suzuki Y, Suzuki M, Koike M, Tamura J, Tong J, Nomura M, Itoh G. Apoptosis is a major mode of cell death caused by ischaemia and ischaemia/reperfusion injury to the rat intestinal epithelium. Gut. 1998;42:530–537. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.4.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock SA, Kyriakides C, Wang Y, Austen WG, Jr, Moore FD, Jr, Valeri R, Hartwell D, Hechtman HB. Soluble P-selectin moderates complement dependent injury. Shock. 2000;14:610–615. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Austen WG, Jr, Chiu I, Alicot EM, Hung R, Ma M, Verna N, Xu M, Hechtman HB, Moore FD, Jr, Carroll MC. Identification of a specific self-reactive IgM antibody that initiates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3886–3891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400347101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl GL, Xu Y, Hao L, Miller M, Buras JA, Fung M, Zhao H. Role for the alternative complement pathway in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:449–455. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63839-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurman JM, Lenderink AM, Royer PA, Coleman KE, Zhou J, Lambris JD, Nemenoff RA, Quigg RJ, Holers VM. C3a is required for the production of CXC chemokines by tubular epithelial cells after renal ishemia/reperfusion. J Immunol. 2007;178:1819–1828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuk RJ, Tangelder GJ, Maassen RL, Quaedackers JS, Heineman E, Oude Egbrink MG. Leucocyte and platelet adhesion in different layers of the small bowel during experimental total warm ischaemia and reperfusion. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1294–1304. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vejchapipat P, Leawhiran N, Poomsawat S, Theamboonlers A, Chittmittrapap S, Poovorawan Y. Amelioration of intestinal reperfusion injury by moderate hypothermia is associated with serum sICAM-1 levels. J Surg Res. 2006;130:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Qiao F, Atkinson C, Holers VM, Tomlinson S. A novel targeted inhibitor of the alternative pathway of complement and its therapeutic application in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2008;181:8068–8076. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binion DG, Rafiee P. Is inflammatory bowel disease a vascular disease? Targeting angiogenesis improves chronic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:400–403. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]