Abstract

Traumatic injury in the central nervous system induces inflammation; however, the role of this inflammation is controversial. Precise analysis of the inflammatory cells is important to gain a better understanding of the inflammatory machinery in response to neural injury. Here, we demonstrated that leukotriene B4 plays a significant role in mediating leukocyte infiltration after spinal cord injury. Using flow cytometry, we revealed that neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage infiltration peaked 12 hours after injury and was significantly suppressed in leukotriene B4 receptor 1 knockout mice. Similar findings were observed in mice treated with a leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist. Further, by isolating each inflammatory cell subset with a cell sorter, and performing quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, we demonstrated the individual contributions of more highly expressed subsets, ie, interleukins 6 and 1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and FasL, to the inflammatory reaction and neural apoptosis. Inhibition of leukotriene B4 suppressed leukocyte infiltration after injury, thereby attenuating the inflammatory reaction, sparing the white matter, and reducing neural apoptosis, as well as inducing better functional recovery. These findings are the first to demonstrate that leukotriene B4 is involved in the pathogenesis of spinal cord injury through the amplification of leukocyte infiltration, and provide a potential therapeutic strategy for traumatic spinal cord injury.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) causes severe motor/sensory dysfunction with limited functional recovery. Mechanical trauma rapidly leads to blood–brain barrier disruption, neuronal cell death, edema, axonal damage, and demyelination, followed by a cascade of secondary injuries that expand the inflammatory reaction, which is characterized by immune cell infiltration and activation of systemic immunity at the lesion area.1,2 Although the role of this inflammatory reaction after SCI remains controversial, extensive evidence suggests that inflammatory cells and proinflammatory cytokines increase tissue damage, induce apoptosis, and impair functional recovery.3,4,5,6,7 Among these inflammatory cells, neutrophils are considered one of the most potent triggers of post-traumatic spinal cord damage, because they induce the release of proteases, reactive oxygen intermediates, and lysosomal enzymes.8 Despite the fact that neutrophils are essential for innate immunity and important anti-infection factors in host defense, some studies have reported that suppressing neutrophil infiltration reduces secondary injury and leads to better functional recovery after SCI.9,10 Neutrophil infiltration into the lesion area is enhanced and amplified by a wide variety of factors, such as pro-inflammatory cytokines, eicosanoids, and adhesion molecules.11

Of these chemotactic factors, leukotriene B4 (LTB4) is a highly potent lipid chemoattractant for neutrophils that is rapidly produced from membrane phospholipids by the arachidonic acid cascade, without requiring transcription and translation.12,13 LTB4 functions through its high-affinity specific receptor, LTB4 receptor 1 (BLT1), which is mainly expressed on neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages.14,15

Previous studies demonstrated that in addition to its involvement in regulating microbial infection, LTB4 is strongly related to several inflammatory diseases and autoimmune diseases.16,17,18 However, the pathophysiologic role of LTB4 in traumatic injury is not well understood. In the present study, we analyzed the pathophysiologic involvement of LTB4 in a mouse SCI model using BLT1-knockout mice and the LTB4 receptor antagonist ONO-4057.

Flow cytometry was used to determine the detailed profile of infiltrating neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and resident microglial cells after SCI. Blockade of the LTB4-BLT1 axis significantly reduced leukocyte infiltration in the lesion area after injury, suppressed inflammatory cytokine/chemokine expression, reduced apoptotic neural cell death, and spared white matter, as well as induced better functional recovery. Furthermore, individual isolation of activated neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and microglial cells from injured spinal cord revealed significantly increased levels of expression of several cytokines/chemokines that contribute to the aggregative inflammatory reaction at the lesion site. Our findings provide a better understanding of the inflammatory reaction after SCI and suggest that the LTB4–BLT1 pathway is a potential therapeutic target.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Adult 8- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6J mice were used in this study. BLT1-knockout mice and wild-type littermates (C57BL/6 background) were generated as described previously.19 All mice were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment on a 12 hours light–dark cycle.

Spinal Cord Injury

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (75 mg/kg i.p.) and were subjected to a moderate (70 kdyn) contusion injury at the 10th thoracic level using an Infinite Horizons Impactor (Precision Systems Instrumentation, Lexington, KY). After injury, the overlying muscles were sutured, and the skin was closed with wound clips. During the recovery from anesthesia, the animals were placed in a temperature-controlled chamber until thermoregulation was re-established. Sham-operated controls were subjected to laminectomy only. All surgical procedures and experimental manipulations were approved by the Committee of Ethics on Animal Experiment in the Faculty of Medicine, Kyushu University. Experiments were conducted under the control of the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation.

Histopathological Examination

Animals were re-anesthetized and transcardially perfused with normal saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PBS. The spinal cord was removed and immersed in the same fixative at 4°C for 24 hours. A spinal segment centered over the lesion epicenter was transferred into 10% sucrose in PBS for 24 hours and 30% sucrose in PBS for 24 hours and embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound. The embedded tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −20°C until needed. Frozen sections of the spinal cord were cut on a cryostat in the sagittal plane at 14 μm, and mounted onto glass slides. Spinal cord sections were permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100 and 10% normal goat serum in PBS, pH 7.4, for 60 minutes. As primary antibodies, rat anti-neutrophils (1:400, Serotec, Oxford, UK), mouse anti-myeloperoxidase (1:50 Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rat anti-CD68 (1:200, Serotec), mouse anti-NeuN (1:1000, Chemicon, Temecula, CA), mouse anti-Tuj-1 (1:200, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), rabbit anti-caspase 8 (1:100 Abcam), and mouse anti-APC-CC1 (1:200, Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) were applied to the sections at 4°C overnight. The sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (1:200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:200, Invitrogen) or Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:200, Invitrogen) were used as secondary antibodies. Negative control experiments included normal spinal cord section with primary, as well as secondary antibody, and injured spinal cord sections incubated with secondary antibody alone or with nonspecific rat/mouse IgG and secondary antibody. For terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay, an ApopTag red in situ kit (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) was used for terminal deoxynucleotide transferase dUTP nick-end labeling. Fluorescently labeled sections were coverslipped with Fluorescent Mounting Medium (S3023; Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). All images were captured on a computer assisted epifluorescence microscope (Biorevo; Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

Quantitative Analysis

For the quantification of the infiltrating neutrophils, we performed immunostaining with anti-neutrophil antibody in every sagittal section at 150-μm intervals from side to side and captured 120 regions with ×100 magnification in each section for the reconstruction of a 4-mm length of sagittal sample sections in each mouse (n = 9 in each group). The algorithms for counting the number of infiltrating neutrophils were provided by the measurement software Dynamic cell count BZ-H1C (Keyence. Co., Osaka, Japan), which counted selectively the immunopositive particles in sizes ranging from 5 μm to 15 μm in both X- and Y- dimensions, and automatically eliminated the spurious particles. For quantification of neural cell apoptosis, we obtained sagittal sections at 150-μm intervals from injured spinal cord in each mouse (n = 6 in each group) and TUNEL-positive cells were counted in the area of 1.0 mm rostral and caudal to the epicenter (2 mm long total). The algorithms for counting the number of TUNEL-positive cells were performed as described above. To evaluate the neuronal cells undergoing apoptosis at 12 hours after injury, we performed NeuN/TUNEL double immunostaining with 150-μm interval sagittal sections of injured spinal cord for each mouse (n = 6 in each group) and counted all NeuN positive cells and NeuN/TUNEL double-positive cells in the area ranging from 250 μm to 750 μm rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter, and calculated the ratio (see Supplemental Figure S1 available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). For quantification of the area of spared white matter, we obtained cross sections, which were stained with Luxol Fast Blue (LFB). Every tenth section was viewed on a light microscope (BZ-9000; Keyence, Osaka, Japan) and the section containing the injury epicenter was defined visually as the one with the smallest visible rim of spared myelin. Then, LFB-stained serial sections at the injury epicenter and at both 500 μm and 1000 μm rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter in each animal (n = 7 wild-type, n = 6 BLT1-knockout) were imaged at ×40 magnification and captured. The LFB-positive area of spared white matter was determined as the percentage of pixels with the same grayscale value on the inverse image using the measurement software of BZII-Analyzer (Keyence). Sham-operated mice were processed similarly to determine the mean volumes of normal-appearing white matter (n = 5 in each group). The ratio of LFB staining of injured tissue compared with normal tissue was then determined.

Flow Cytometry

At 4 hours, 12 hours, 1 day, 3 days, and 7 days after SCI, animals were re-anesthetized with pentobarbital (75 mg/kg i.p.), perfused with ice-cold PBS to remove circulating blood from the vasculature, and the spinal cord was rapidly dissected from the vertebral column and placed into ice-cold PBS. Spinal cord samples were then prepared for flow cytometry analysis (n = 6 in each time point and each group). For control spinal cord samples, we used sham-operated mice 24 hours after the surgery (n = 6 in each group). Spinal cords (one spinal cord per sample) were mechanically dissociated with collagenase (175 U/ml; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were washed in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and passed through a 40 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to isolate tissue debris from the cell suspension. For blood samples, we used naïve mice and the blood was collected by cardiac puncture. After red blood cells were removed by hypotonic lysis buffer (17 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.2; 100 mmol/L NH4Cl), the resulting suspension was pelleted by centrifugation and washed twice in PBS. The resulting suspension from spinal cord and blood samples was subjected to centrifugation, and the pellet was resuspended, followed by a 5-minute incubation on ice with Fc block and a 30 minutes incubation on ice with the fluorescent antibodies. For allophycocyanin (APC), conjugated streptavidin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was added to label the biotin-conjugated antibodies. Samples were stained with the following antibodies: phycoerythrin-Cy7-conjugated CD45 (eBioscience), fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated CD11b (eBioscience), phycoerythrin-conjugated Gr-1 (eBioscience), biotin-conjugated MHC class II (eBioscience). Before analysis, propidium iodide was added to determine the cell viability. All of the samples were suspended in 500 μl of buffer and analyzed at the same flow rate and same duration to allow comparison of all samples using FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The data were analyzed using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). We calculated the total number of infiltrating neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages and resident microglial cells within the injured spinal cord. We decided the spinal cord sample length was accurately 6 mm long because the number of these cells in the 6-mm long sample was equivalent to the number in the 10-mm long sample. The average sample weight is 15.39 ± 0.31 mg (values are means ± SEM). For cell morphological studies, cytospin preparations were stained by Diff-Quik (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan).

Co-Culture of Neutrophils and Neural Cells

Primary neural cell cultures were prepared from the mouse spinal cord on embryonic day 13. The spinal cord was dissected and cells were dissociated by incubation in 0.025% trypsin solution (Nacalai Tesque, Tokyo, Japan) for 5 minutes. The solution was removed, and the tissue was resuspended in a separate culture medium. The culture medium comprised Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)/F12, supplemented with a hormone solution that included insulin (25 μg/ml), transferrin (100 μg/ml), progesterone (20 nmol/L), putrescine (60 μmol/L), and selenium chloride (30 nmol/L), and was dissociated by trituration with a fire-polished glass pipette.20 The cell suspension was centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 minutes and the pellet was resuspended in the medium. The cells (5.0 × 105 cells/well) were plated in poly-l-lysine-coated 24-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C. We isolated circulating neutrophils from naïve wild-type mice and infiltrating neutrophils from injured spinal cord of wild-type and BLT1 knockout mice using a cell sorter and added 5.0 × 104 neutrophils per well to 5-day-old spinal cord cultures. Co-cultures were maintained for 12 hours at 37°C. Control cultures (no neutrophils) received an equivalent amount of culture medium. To assess neural cell viability, we used Live-Dead Cell Staining Kit (Bio Vision, Mountain View, CA). After staining, the number of dead cells per mm2 was calculated using Image J software (n = 8 in each group).

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR

We isolated total RNA from the injured spinal cord (6 mm long, n = 6 in each group) using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was primed with oligo dT primer and reverse transcribed using PrimeScript reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). Real time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed using primers specific to the genes of interest (Table 1) and SYBR Premix Ex TaqII (TaKaRa) in 20 μl of reactions. BLT1 primer sequences were taken from the literature.21 The levels of mRNA were normalized to the level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA for each sample. To evaluate the mRNA expression of each inflammatory cell fraction, we isolated neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages from peripheral blood and injured spinal cord and isolated microglial cells from uninjured and injured spinal cord individually at 12 hours after SCI using a FACSAria II flow cytometer. To analyze BLT1 expression in various mouse tissues, we isolated brain, spinal cord, leukocytes, liver, lung, muscle, and injured spinal cord from wild-type and BLT1-knockout mice. cDNA was synthesized from mRNA extracted from these tissues. RT-PCR was conducted using a Thermocycler (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) and the products were detected by electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

Table 1.

Primers Used for Real Time RT-PCR and Conventional RT-PCR

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | 5′-GGGCTGGACTGTTTCTAATGCCTT-3′ | 5′-CCATCAGAGGCAAGGAGGAAAACA-3′ |

| IL-6 | 5′-GCTCTCCTAACAGATAAGCTGGAG-3′ | 5′-CCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCACAAAC-3′ |

| TNF α | 5′-TTTCCAGATTCTTCCCTGAGGTGC-3′ | 5′-TGTCTGAAGACAGCTTCCCACACT-3′ |

| CXCL1 | 5′-GGGAGGCTGTGTTTGTATGTCTTG-3′ | 5′-CGAGACCAGGAGAAACAGGGTTAA-3′ |

| CXCL2 | 5′-CGGATGGCTTTCATGGAAGGAGTG-3′ | 5′-GCTAAGCAAGGCACTGTGCCTTAC-3′ |

| CCL2 | 5′-CCTGGATCGGAACCAAATGAGATC-3′ | 5′-CCGAGTCACACTAGTTCACTGTCA-3′ |

| CCL3 | 5′-GCTGTTTGCTGCCAAGTAGCCACA-3′ | 5′-CCAAACAGTGTGACCAACTGGGAG-3′ |

| CCL5 | 5′-CCAGCAGCAAGTGCTCCAATCTTG-3′ | 5′-GCTGGCTAGGACTAGAGCAAGCAA-3′ |

| FasL | 5′-TGTGACAATGCAGAGGCACAGAGA-3′ | 5′-ATGAGCCTCCTTTCTCACCCTTGT-3′ |

| Fas | 5′-TTCAGGACATGGTCCAGAAGGACC-3′ | 5′-TGCTGGCAAAGAGAACACACCAGG-3′ |

| Caspase8 | 5′-TTCCTACCGAGATCCTGTGAATGG-3′ | 5′-AGAGCTTCTTCCGTAGTGTGAAGG-3′ |

| BLT1 | 5′-ATGGCTGCAAACACTACATCTCCT-3′ | 5′-CACTGGCATACATGCTTATTCCAC-3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′-GACTTCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCT-3′ | 5′-GGTTTCTTACTCCTTGGAGGCCAT-3′ |

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

At 12 hours after SCI, animals were re-anesthetized and the spinal cord (6 mm centered around the lesion area) was rapidly dissected after circulating blood was removed (n = 5 in each group). These spinal cord samples were then homogenized in sodium phosphate buffer (20 mmol/L, pH 7.2) and protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C, the remaining supernatants were used for measurements with a quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique. We measured the sample concentration of interleukin (IL)-6 using a mouse IL-6 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Bender Medsystems, Vienna, Austria) and IL-1β using a mouse IL-1β ELISA kit (Bender Medsystems), following the manufacturer’s instructions with a microplate reader (ImmunoMini NJ2300, BioTec, Tokyo, Japan) at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Immunoblotting

Six mm segments of sham or injured spinal cord were extracted from BLT1-knockout and wild-type mice (n = 5 per SCI group, n = 3 per sham group) to assess total proteins. These spinal cord samples were individually homogenized in a buffer (5 mmol/L Tris–HCl, 4 mmol/L EDTA, 1 μmol/L pepstatin, 100 μmol/L leupeptin, 100 μmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin) at 4°C. The whole tissue lysate of extracted spinal cord was separated by 10% sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel, and electrophoresis, and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with a blocking solution containing 5% skim milk in TBS-T (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20), and then incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-caspase 8 rabbit polyclonal antibody (#9429 1:1000 Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) diluted in a blocking solution. After washing with TBS-T, the membranes were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (NA9340V, GE Health care, UK). After washing with TBS-T, the membranes were detected by LAS-3000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan).

Analysis of Locomotor Function

We examined the wild-type SCI mice group (n = 29) and the BLT1-knockout SCI mice group (n = 27) for functional evaluation. Assessment of functional recovery began on postoperative day 1. Motor function of their hindlimbs was evaluated with a locomotor open field rating scale on the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS).22 Each mouse was assessed on day 1 and day 7 postoperatively and weekly thereafter until 6 weeks. A team of three independent examiners evaluated each animal for 4 minutes and assigned an operationally defined score for each hindlimb. Every test was performed in a double-blinded fashion.

Electrophysiological Assessment for Functional Recovery

We re-anesthetized SCI mice (6 weeks post-injury) and performed a T5–L2 laminectomy to record spinal cord evoked potentials (n = 9 in each group). Electrodes developed for mice spinal cord electrophysiological assessment (Unique Medical, Tokyo, Japan) were used for stimulation at T5–6 and recording of compound action potentials at L1–2. These electrodes were positioned precisely 10 mm apart on the dorsal surface of the midline spinal cord. Sham-operated mice were used as controls. A NeuropackM1 two-channel evoked potential measuring unit (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) was used in these studies. The spinal cord was stimulated at 4 Hz, 0.05 ms pulse duration, and 1 mA constant current intensity for an average of 10 sweeps. The amplitude of the compound action potential was calculated as the value between the positive and negative peaks of the biphasic wave. Conduction velocity was calculated by dividing the conduction distance by the conduction time as determined by the latency. At the end of each experiment, the dorsal columns and corticospinal tract were transected between stimulating and recording electrodes to confirm that a compound action potential could not be detected.

LTB4 Receptor Antagonist (ONO-4057) Administration

Wild-type mice were subjected to spinal cord injury as described in the previous section. Either ONO-4057 (supplied by Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Osaka, Japan; 10 mg/kg in 2.1% sodium bicarbonate, i.p.) or vehicle (2.1% sodium bicarbonate, i.p.) was administered to the mice immediately after SCI and then every 24 hours (10 mg/kg in 2.1% sodium bicarbonate, i.p.) for the first 5 days after injury. To investigate the effect of ONO-4057 in SCI, we evaluated the number of infiltrating inflammatory cells within the injured spinal cord (n = 5 in each group) and the mRNA expression levels of several cytokines/chemokines and apoptosis-related factors (n = 6 in each group). We also evaluated the functional recovery based on the BMS score in ONO-4057 treated and vehicle-treated mice (n = 15 in each group).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluations were performed with Mann–Whitney U-test. For multiple comparisons between groups, a Kruskal Wallis H test, with Bonferroni’s post hoc correction, was used. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data in graphs are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Selective Expression of BLT1 in Leukocytes

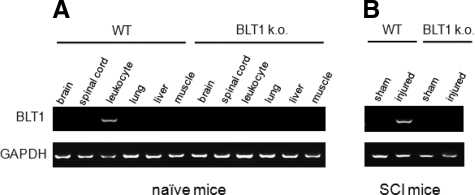

To investigate which organs express the high-affinity LTB4 receptor BLT1, we removed brain, spinal cord, leukocytes, liver, lung, and muscle from naïve wild-type mice and BLT1-knockout mice and performed RT-PCR analysis. In wild-type mice, BLT1 was expressed only in the leukocytes and not in any other tissues, including spinal cord. We confirmed its exclusive expression in neutrophils and monocytes (data not shown). BLT1 was not expressed in any tissues in BLT1-knockout mice (Figure 1A). At 12 hours after SCI, BLT1 was expressed in injured spinal cord in wild-type mice, but not in BLT1-knockout mice (Figure 1B), suggesting that the BLT1 expression detected in wild-type mice was due to leukocyte infiltration into the lesion area.

Figure 1.

Selective expression of BLT1 in leukocytes. A: BLT1 expression was examined by RT-PCR in various tissues in naïve wild-type and BLT1-knockout mice. BLT1 was expressed only in the leukocytes and not in any other tissues, including spinal cord in wild-type mice. B: At 12 hours after SCI, BLT1 was expressed in injured spinal cord in wild-type, but not in BLT1-knockout mice.

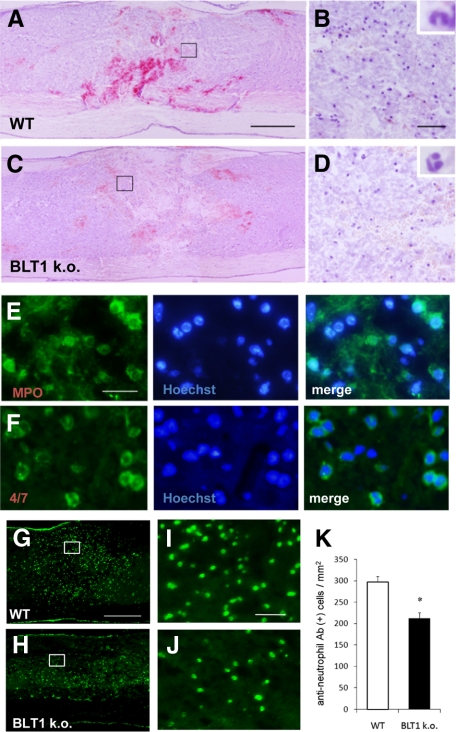

Histological Analysis of Neutrophil Infiltration after SCI

To analyze the role of the LTB4–BLT1 pathway in traumatic SCI, we examined neutrophil infiltration in injured spinal cord. Because the lesion area itself is too fragile to treat, few studies have analyzed injured spinal cord sections in the acute phase. We successfully prepared cryostat sections of spinal cord at 12 hours after injury by longer fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde and careful handling. Sagittal sections stained with H&E showed massive hemorrhage and widespread infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (Figure 2, A and B). Immunohistochemistry using anti-myeloperoxidase or anti-neutrophil antibodies showed a large number of infiltrating neutrophils at 12 hours after SCI (Figure 2, E and F). The infiltrated area in the rostral–caudal direction was much wider than the diameter of the impactor (the area of direct injury), suggesting that the area of secondary injury had enlarged within several hours after injury due to a robust inflammatory response. Because LTB4 production at the lesion site is increased during the acute phase of SCI,23 we assessed neutrophil infiltration in BLT1-knockout mice. Hemorrhage and neutrophil infiltration were attenuated at 12 hours after injury in BLT1-knockout mice (Figure 2, C and D). To quantify the infiltrating neutrophils, we counted the number of cells immunopositive for anti-neutrophil antibody in both genotypes (Figure 2, G–J). Neutrophil infiltration was significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice (211.8 ± 14.0 cells/mm2, mean ± SEM) as compared with wild-type mice (296.9 ± 13.0 cells/mm2, P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 2K). These findings indicate that the LTB4–BLT1 axis has a significant role in neutrophil infiltration in the acute phase of SCI.

Figure 2.

BLT1-knockout mice showed suppressed neutrophil infiltration after SCI in histological evaluation. A and B: Massive hemorrhage and widespread infiltration of polymorphonuclear neutrophils were observed in hematoxylin and eosin stained sagittal sections of wild-type mice spinal cords. Image in (B) is a magnification of the boxed area in (A). C and D: Less hemorrhage and less neutrophil infiltration are observed in the section from BLT1-knockout mice at 12 hours after SCI. Image in (D) is a magnification of the boxed area in (C). Insets in (B) and (D) show the characteristic lobulated nuclei of the neutrophils. E and F: Immunostaining for anti-myeloperoxidase (E) or anti-neutrophil (F) antibody showed a large number of infiltrating neutrophils in the lesion area in wild-type mice at 12 hours after SCI. G and H: Injured spinal cord sections immunostained for anti-neutrophil antibody show that BLT1-knockout mice (H) have a reduced number of infiltrating neutrophils at the lesion area 12 hours after SCI compared with wild-type mice (G). Images in I and J are magnification of the boxed area in G and H. K: For quantitative evaluation of neutrophil infiltration, anti-neutrophil-immunopositive neutrophils were counted. The number of infiltrating neutrophils is significantly lower in BLT1-knockout mice at 12 hours after SCI. *P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, the error bar indicates SEM. Scale bars: 500 μm (A, C, G); 50 μm (B, D, I, J); and 20 μm (E).

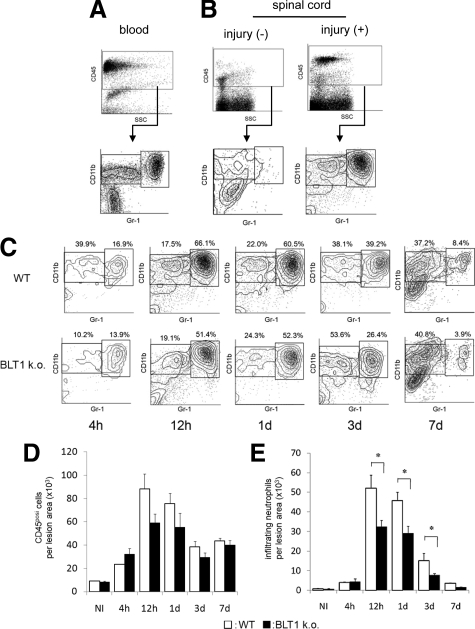

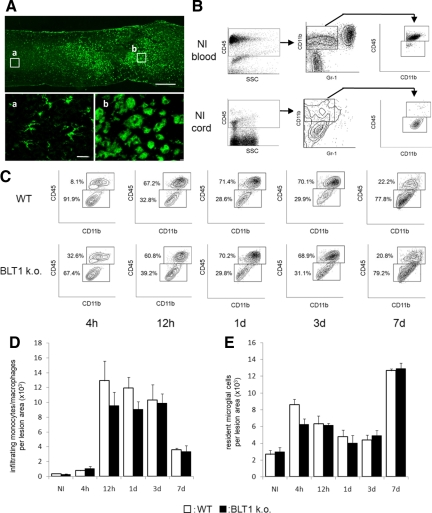

Temporal Change in Neutrophil Infiltration and Quantitative Analysis by Flow Cytometry

Although we confirmed in histopathological sections that a large number of neutrophils infiltrated the lesion area at 12 hours after SCI, the time course of neutrophil infiltration remained unclear. For a more precise and quantitative evaluation, we used flow cytometry to assess the changes in neutrophil infiltration at 4 hours, 12 hours, 1 day, 3 days, and 7 days after SCI. CD45-positive cells in spinal cord tissue were subfractionated into CD11bposi/Gr-1high and CD11bposi/Gr-1neg-int populations. Neutrophils were detected in the CD11bposi/Gr-1high population, which is a commonly used population to detect neutrophils.24,25,26 We first confirmed that peripheral blood could be clearly fractionated to CD11bposi/Gr-1high neutrophils, CD11bposi/Gr-1neg-int monocytes, and CD11bneg/Gr-1neg lymphocyte populations (Figure 3A). In uninjured spinal cord, few neutrophils were present in the spinal cord tissue, suggesting that in a normal physiological state the influx of neutrophils is strictly regulated by the blood–brain barrier. Twelve hours after SCI, a large number of neutrophils was detected at the lesion area (Figure 3B). Although a scatter plot analysis of the transient distribution profile of infiltrating leukocytes revealed a similar distribution in both types of mice, in BLT1 knockout mice the total CD45-postive cell number in the lesion area was reduced during the acute phase of injury when neutrophil infiltration was the most prominent (Figure 3, C–E). At 4 hours after SCI, the total number of infiltrating neutrophils in the lesion area in wild-type mice was relatively low (3978 ± 243 cells/whole injured spinal cord; Figure 3, C and E, see Supplemental Table S1 available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The proportion of CD11bposi/Gr-1high cells dramatically increased at 12 hours after SCI and remained at a high level for up to 24 hours after SCI, suggesting that several hours were required for neutrophil activation and infiltration into the lesion area in this injury model. The proportion of neutrophils was slightly smaller at 3 days after SCI and continued to decrease thereafter. In BLT1-knockout mice, the temporal change in neutrophil infiltration after SCI was similar to that in wild-type mice. It is notable that the number of infiltrating neutrophils at 4 hours after injury was comparable in BLT1-knockout mice (4484 ± 1356 cells/whole injured spinal cord). At 12 hours, 1 day, and 3 days after SCI, however, the proportion of infiltrating neutrophils was significantly lower than that in wild-type mice (Figure 3, C and E). Subsequently, the proportion of neutrophils in BLT1-knockout mice was comparable with wild-type mice at a later phase of injury. These findings suggest that the LTB4-BLT1 pathway strongly influences neutrophil infiltration in the acute phase of SCI.

Figure 3.

Quantitative time course evaluation of neutrophil infiltration by flow cytometry. A: Flow cytometry analysis with peripheral blood from uninjured mice showed clear fractionation of neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages. B: CD45posi cells in spinal cord tissue were subfractionated into a CD11bposi/Gr-1high neutrophil population and a CD11bposi/Gr-1nega-int population including monocytes/macrophages and microglial cells. In uninjured mice, few neutrophils were present in spinal cord tissue. In SCI mice, a large number of neutrophils was detected at the lesion area. C: After SCI, a large number of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages infiltrated the lesion area. The numbers in scatter plots show the percentage of these fractions to the total CD45posi cell fraction. D: The temporal changes of total CD45posi cell infiltration were similar at any time points between wild-type and BLT1-knockout mice. E: Although the temporal changes of infiltrating neutrophils also exhibited a similar pattern between wild-type and BLT1-knockout mice, the number of infiltrating neutrophils in BLT1-knockout mice was significantly lower at 12 hours, 1 day, and 3 days after SCI than in wild-type mice. *P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Error bars indicate SEM.

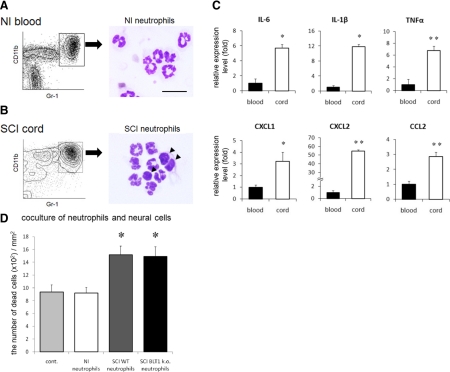

Infiltrating Neutrophils Directly Enhance the Inflammatory Reaction in the Lesion Area

To further evaluate the direct effect of activated neutrophils on the inflammatory reaction after SCI, we isolated neutrophils from peripheral blood of naïve mice and infiltrating neutrophils from the lesion area of injured spinal cord using a cell sorter, and compared the mRNA expression levels of several cytokines/chemokines by quantitative RT-PCR. All of the neutrophils isolated from peripheral blood exhibited characteristic multilobulated nuclei, as revealed by Diff-Quik staining (Figure 4A). Some of the infiltrating neutrophils from the lesion area were band cells, indicating an increase in immature neutrophils (Figure 4B arrowheads). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α, chemokine C-X-C ligands (CXCL)1 and 2, and chemokine C-C ligand (CCL)2 mRNA was significantly elevated in infiltrating neutrophils compared with that in neutrophils from peripheral blood (Figure 4C). This finding suggests that infiltrating neutrophils are activated and potent sources of inflammatory mediators.

Figure 4.

Infiltrating neutrophils isolated from injured spinal cord exhibited enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. A: CD11bposi/Gr-1high neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood in naïve mouse by cell sorting. All of the neutrophils have characteristic multilobulated nuclei. B: Neutrophils isolated from injured spinal cord. Some neutrophils are immature band cells (arrowheads). C: The mRNA expression of several cytokines/chemokines was measured by quantitative RT-PCR to compare nonactivated neutrophils and activated neutrophils. IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, CXCL1, CXCL2, and CCL2 mRNA expression was significantly increased in infiltrating neutrophils, as compared with that in circulating neutrophils from peripheral blood. D: In vitro evaluation of neurotoxic neutrophil effects on spinal cord neural cells. A significantly greater number of dead neural cells was observed in co-culture with activated neutrophils compared with that of circulating neutrophils or controls. No significant difference in neurotoxicity was observed between genotypes of activated neutrophils. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U-test in (C), Kruskal Wallis H test with Bonferroni’s post hoc correction in (D). Error bars indicate SEM.

To determine the effects of infiltrating neutrophils on neural cells, we evaluated the neural cell viability when co-cultured with circulating neutrophils or activated neutrophils from injured spinal cord of the two genotypes. Although the number of dead cells in the co-culture with circulating neutrophils was comparable with that of the control group (control group, 937.2 ± 109.7 cells/mm2; circulating neutrophil group, 919.8 ± 85.0 cells/mm2), the number of dead neural cells was significantly increased in the co-culture with activated neutrophils isolated from injured spinal cord (infiltrating wild-type neutrophil group, 1516.6 ± 134.3 cells/mm2; infiltrating BLT1 knockout neutrophil group 1489.1 ± 134.3 cells/mm2; P < 0.05 vs. the control group and circulating neutrophil group, Kruskal Wallis H test with Bonferroni’s post hoc correction, Figure 4D). This finding indicates that infiltrating neutrophils have a neurotoxic effect. The neurotoxicity of activated neutrophils, however, did not significantly differ between the genotypes.

Quantitative Evaluation of Monocyte/Macrophage Infiltration and Activation of Microglial Cells

Because infiltrating monocytes/macrophages and activated microglial cells were also involved in the inflammatory reaction after SCI, we assessed the effect of LTB4–BLT1 on their infiltration after SCI. The cell morphology of monocytes/macrophages and resident microglial cells in injured spinal cord sections was different, but both cell types were ED-1 immunopositive (Figure 5A, a and b). Therefore, selective quantification of the number of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages distinct from resident microglial cells was not possible in histopathological analysis. Because the CD45 expression level in circulating monocytes/macrophages was higher than that in resident microglial cells, however, monocytes could be distinguished from resident microglial cells by flow cytometry analysis (Figure 5B). The temporal change in these cell numbers was therefore quantitatively analyzed in the injured spinal cord (Figure 5C). Although there was no statistically significant difference at any time point, the total number of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages was suppressed during the acute phase of injury in BLT1-knockout mice compared with wild-type mice (Figure 5D). The number of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages was reduced at a later phase, while the number of resident microglial cells increased dramatically at 7 days after SCI (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Flow cytometric analysis enables individual quantitative evaluation of the number of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages and resident microglial cells. A: The cell morphology of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages and resident microglial cells in injured spinal cord sections was different, but both cell types were ED-1 immunopositive. Boxed area (a): ED-1 immunopositive non-activated microglial cells. Boxed area (b): ED-1 immunopositive infiltrating monocytes/macrophages and activated microglial cells. B: In normal peripheral blood, a CD45high/CD11bposi/Gr-1nega-int monocyte/macrophage fraction was prominent, whereas a CD45int/CD11bposi/Gr-1nega-int fraction was scarce. In contrast, in normal spinal cord, the resident microglial cell fraction was prominent whereas the monocyte/macrophage fraction was scarce. C: After SCI, the monocyte/macrophage fraction is sharply distinguishable from the resident microglial cell fraction by flow cytometric analysis. The numbers in dot plots show the percentage of these fractions to total CD45posi/CD11bposi/Gr-1nega-int cell fraction. D: Temporal changes in infiltrating monocytes/macrophages numbers after SCI. Although monocyte/macrophage infiltration was minimal at 4 hours after SCI, their infiltration was dramatically increased at 12 hours after SCI. E: Temporal change of resident microglial cells has a completely different pattern from that of other leukocytes. Activated microglial cells dramatically increase in number at the lesion area at 7 days after SCI. Scale bars: 500 μm (A); and 20 μm (a).

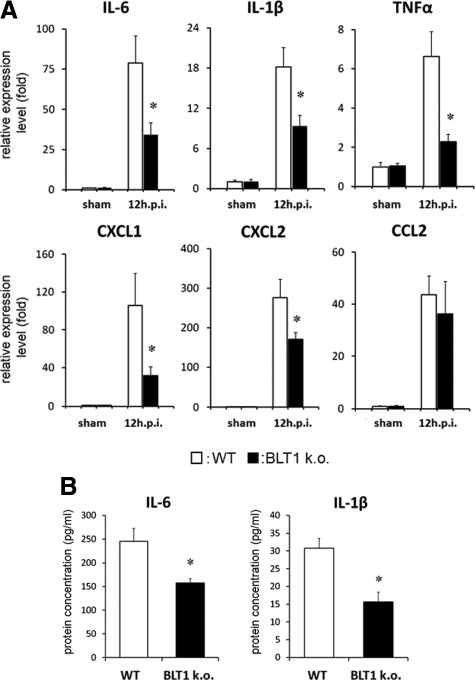

Inflammatory Cytokine/Chemokine Expression Was Suppressed after SCI in BLT1-Knockout Mice

LTB4 amplifies the initial inflammatory reaction in several inflammatory diseases by regulating neutrophil infiltration.27,28 Because we confirmed their direct contribution to the modulation of infiltrating leukocytes after SCI, the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, CXCL1, CXCL2, and CCL2 were measured in whole injured spinal cord in both genotypes. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, CXCL1, and CXCL2 was significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice compared with wild-type mice at 12 hours after SCI (Figure 6A). This finding suggests that the amount of neutrophil infiltration at the lesion site of the injured spinal cord greatly influenced the inflammatory reaction. We also measured IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations in homogenate samples at 12 hours after SCI by ELISA. The production of various cytokines at the lesion area was significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice (IL-6: wild-type, 245.0 ± 27.0 pg/ml; BLT1-knockout, 157.6 ± 8.8 pg/ml; IL-1β: wild-type, 30.8 ± 2.7 pg/ml; BLT1-knockout, 15.6 ± 2.7 pg/ml, P < 0.05; Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Suppressed expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines in the whole lesioned spinal cord in BLT1-knockout mice. A: Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure the mRNA expression for several cytokines/chemokines. Total mRNA was extracted from naïve and injured spinal cord (6 mm long) at 12 hours after SCI. We confirmed dramatic upregulation of these cytokines/chemokines after SCI. IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, CXCL1, and CXCL2 mRNA expression was significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice compared with wild-type at 12 hours after SCI. B: IL-6 and IL-1β concentrations in the injured spinal cord at 12 hours after injury were measured by ELISA. In BLT1-knockout mice, these cytokine levels were significantly lower than those in wild-type mice. *P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, error bars indicate SEM.

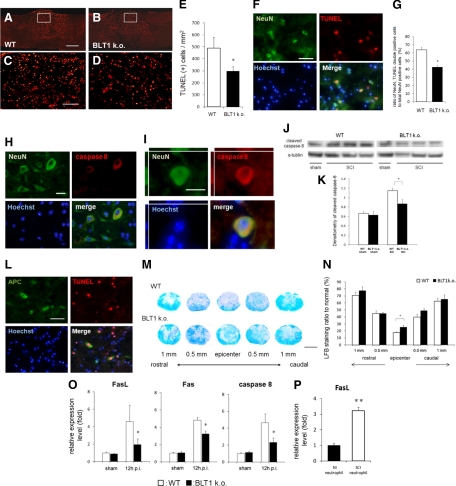

Apoptotic Cells Were Reduced after SCI in BLT1-Knockout Mice

Infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages are considered to exacerbate post-traumatic spinal cord damage, so we evaluated the pathophysiologic changes in injured spinal cord, focusing on tissue apoptosis. To examine the extent of apoptosis after SCI, we analyzed injured spinal cord tissue at 12 hours after injury, when the amount of infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages was the highest in this model. TUNEL staining of injured spinal cord sections indicated a number of cells undergoing apoptosis (Figure 7A–D). Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the number of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells was significantly smaller in BLT1-knockout mice (297.5 ± 38.3/mm2), as compared with that in wild-type mice (490.9 ± 89.1/mm2, P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 7E). We next focused on the specific cells undergoing apoptosis around the lesion epicenter. Double immunostaining using TUNEL and NeuN antibodies showed a large number of apoptotic neurons around the lesion area (Figure 7F). The ratio of NeuN/TUNEL double-positive cells to total NeuN-positive cells was significantly smaller in BLT1-knockout mice (42.7 ± 1.5%) compared with that in wild-type mice (63.7 ± 5.4%, P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 7G). To more specifically evaluate the death receptor-mediated apoptosis pathway, we examined caspase 8 expression in the injured spinal cord. We observed NeuN and caspase 8 double-immunostained cells around the lesion area 12 hours after SCI (Figure 7, H and I). A comparison of caspase 8 expression levels in BLT1-knockout and wild-type mice based on immunoblot analysis revealed that the expression level of cleaved caspase 8 was significantly decreased in BLT1-knockout mice (Figure 7, J and K). Double- immunostaining for TUNEL and APC-CC1 revealed apoptotic oligodendrocytes around the lesion area (Figure 7L). Because oligodendrocyte apoptosis contributes to demyelination, we evaluated white matter sparing in LFB-stained sections. For quantitative and stereologic evaluation, we measured the LFB-positive area of spared white matter in cross-sections of the injury epicenter and at 500 μm and 1000 μm rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter in each animal. A significantly higher LFB-staining ratio was observed at the epicenter in BLT1-knockout mice (25.5 ± 2.50%) than in wild-type mice (17.8 ± 0.88%, P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 7, M and N). We also evaluated mRNA expression levels of factors involved in the death receptor-mediated apoptosis pathway in injured spinal cord, ie, FasL, Fas, and caspase 8. These factors were significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice at 12 hours after SCI (Figure 7O). To confirm the involvement of neutrophils in the apoptotic effect, we isolated infiltrating neutrophils from injured spinal cord and analyzed their FasL mRNA expression levels. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis revealed that FasL expression was significantly elevated in activated neutrophils (Figure 7P).

Figure 7.

Apoptotic neural cells were reduced after SCI in BLT1-knockout mice. A, B, C, and D: A great number of apoptotic cells were observed in the spinal cord sections stained with TUNEL (A and B). Image in C is a magnification of the boxed area in A. Image in D is a magnification of the boxed area in B. E: Quantitative analysis of the immunohistochemistry revealed that the number of TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells was significantly less in BLT1-knockout mice at 12 hours after SCI compared with wild-type mice. F: NeuN and TUNEL double-positive apoptotic neurons were observed around the lesion area. G: The ratio of NeuN/TUNEL double-positive cells to total NeuN-positive cells was significantly smaller in BLT1-knockout mice compared with that in wild-type mice. H and I: NeuN and caspase 8 double-positive neurons were observed within the perilesional area. J and K: Densitometric scanning of the immunoblots showed a significant decrease in expression of cleaved caspase 8 in BLT1-knockout mice, in comparison with wild-type 12 hours after SCI. L: Around the lesion area, both viable (APC-CC1 single-positive) and apoptotic (APC-CC1, TUNEL double-positive) oligodendrocytes were observed. M: Low magnification imaging of LFB-stained cross-sections of injury epicenter and at 500 μm and 1000 μm rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter in each animal. N: A significantly higher LFB-staining ratio was observed at the epicenter in BLT1-knockout mice than in wild-type mice. O: Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure the mRNA expression for apoptosis-related factors. mRNA was extracted from injured spinal cord at 12 hours after SCI. Fas, FasL and caspase8 mRNA expression was significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice compared with wild-type. P: The expression of FasL mRNA was significantly elevated in infiltrating neutrophils isolated from injured spinal cord at 12 hours after SCI compared with that in circulating normal neutrophils. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Mann–Whitney U-test, Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars: 1 mm (M); 500 μm (A); 50 μm (C, F, L); and 20 μm (H, I).

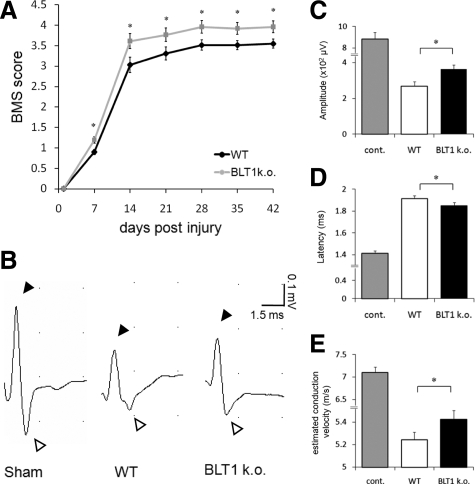

Better Locomotor Recovery and Greater Improvement of Axonal Conduction in BLT1-Knockout Mice after SCI

Given the histopathological improvements, such as suppression of neutrophil infiltration, neuronal apoptosis, and greater white matter sparing in BLT1-knockout mice, we examined the recovery of locomotor function after SCI in both genotypes. We assessed the open-field score using BMS, which is specialized for mouse hindlimb motor function (Figure 8A). As compared with the wild-type mice, the BMS score revealed a significantly better functional recovery at each time point after SCI in BLT1-knockout mice (wild-type: n = 29, BLT1-knockout: n = 27). We also performed an electrophysiologic assessment using spinal cord evoked potentials to evaluate functional recovery in wild-type and BLT1-knockout mice after SCI. Stimulating electrodes and recording electrodes were placed precisely 10 mm apart using a divider to obtain reproducible data. All of the recording data from SCI mice showed positive and negative peaks of the biphasic wave that were similar to those of sham-operated intact spinal cord (Figure 8B). Our results demonstrated increased amplitude (wild-type: 269.1 ± 25.7 μV, BLT1-knockout: 363.8 ± 24.3 μV; P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, Figure 8C) and decreased latency (wild-type: 1.913 ± 0.027 ms, BLT1-knockout: 1.85 ± 0.028 ms; P < 0.05, Figure 8D) in BLT1-knockout mice compared with wild-type mice after SCI. We estimated conduction velocity by dividing the recording distance by the conduction velocity, and found increased conduction velocity in BLT1-knockout mice (wild-type: 5.24 ± 0.070 m/s, BLT1-knockout: 5.42 ± 0.079 m/s; P < 0.05, Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

Significantly better locomotor recovery and greater improvement of axonal conduction in BLT1-knockout mice after SCI. A: Compared with the wild-type mice, the BMS score revealed a significantly better functional recovery at each time point after SCI in BLT1-knockout mice. B: Representative compound action potential responses from sham-operated, wild-type, and BLT1 knockout mice. All of the recording data from SCI mice showed positive (solid arrowheads) and negative (white arrowheads) peaks that had the same configuration in sham-operated intact spinal cord. C, D, and E: Action potentials from BLT1-knockout mice showed significantly increased amplitude (C), decreased latency (D), and increased estimated conduction velocity (E), as compared with wild-type mice after SCI. *P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, error bars indicate SEM.

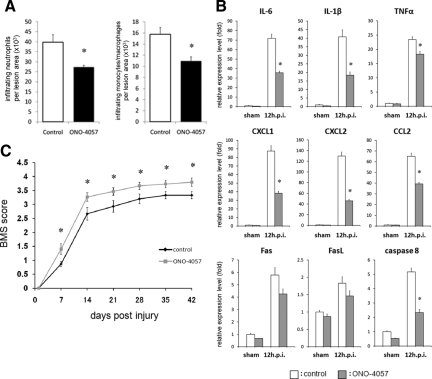

Effects of LTB4 Receptor Antagonist (ONO-4057) Administration after SCI

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of blockade of the LTB4-BLT1 axis after SCI, we analyzed SCI mice that were treated with the specific LTB4 receptor antagonist ONO-4057. Because the amount of neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage infiltration was highest at 12 hours after SCI in this model, we performed a quantitative evaluation of infiltrating leukocytes within the lesion area of SCI mice treated with ONO-4057 at 12 hours after injury. The findings indicated that the amount of neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage infiltration was significantly suppressed in ONO-4057 treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figure 9A). To further evaluate the effect of ONO-4057 on the inflammatory reaction at the lesion area, we performed real time RT-PCR to measure the mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and apoptosis-related factors at 12 hours after SCI. We confirmed that the expression levels of IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL2, and caspase 8 were significantly suppressed in ONO-4057 treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figure 9B). In addition, significantly better functional recovery after SCI was observed in ONO-4057 treated mice, as compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

Effect of ONO-4057 administration after SCI. A: The number of infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages was quantified at 12 hours after injury. There was a significant reduction in the number of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in mice treated with ONO-4057 compared with vehicle-treated controls. B: IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα, CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL2, and caspase 8 mRNA expression was significantly suppressed in ONO-4057 treated mice compared with vehicle-treated mice at 12 hours after SCI. C: ONO-4057-treated mice had significantly better functional recovery than vehicle-treated mice based on the BMS scores at each time point after SCI. *P < 0.05, Mann–Whitney U-test, error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

LTB4 plays an important role in a wide variety of inflammatory reactions. Direct involvement of the LTB4–BLT1 axis in the pathophysiology of SCI, however, has not yet been evaluated. Previous studies using BLT1 antagonists or BLT1-knockout mice report that BLT1 blockade drastically suppresses neutrophil infiltration in several inflammatory disease models such as rheumatoid arthritis and peritonitis, resulting in amelioration of the disease condition.27,28,29,30,31 These studies revealed that neutrophil infiltration into the inflammatory site was mainly dependent on the LTB4–BLT1 axis and its deficiency leads to an amelioration of tissue inflammation. Thus, LTB4 mediates neutrophil infiltration upstream of other chemoattractants. Considering that the major function of this pathway is potent chemotaxis, firm adhesion, and degranulation of neutrophils,12,32,33 we examined whether the LTB4–BLT1 pathway has a potent effect on the inflammatory reaction induced by traumatic SCI in BLT1-knockout mice.

Detailed profiling of infiltrating leukocytes and activated microglial cells at the lesion area cannot be precisely evaluated with conventional histopathology. In this study, we used flow cytometry to accurately detect and directly isolate these cells. First, we quantitatively examined the detailed profile of infiltrating leukocytes in the lesion area (Figure 3). The infiltrating neutrophil population increased dramatically 12 hours after SCI and remained at a high level for up to 1 day, then gradually decreased. Although our flow cytometry findings were consistent with biochemical and histopathological analyses in other animal models and human studies of SCI,3,34,35 flow cytometry has the great advantage of providing a more quantitative analysis and simultaneously identifying a wide variety of inflammatory cell subsets, as previously reported.26 Until now, it has been commonly accepted that in human SCI the peak of monocyte/macrophage infiltration is observed at a later phase that that of neutrophil infiltration.35,36,37 Our results clearly demonstrate that monocyte/macrophage infiltration peaks at 12 hours after SCI, simultaneous with neutrophil infiltration. In addition, the temporal change in the number of infiltrating monocytes/macrophages was completely different from that of microglial cells, which dramatically increased at 7 days after SCI (Figure 5, D and E). We attribute this discrepancy with previous reports to the immunohistologic analyses, in which it is difficult to discriminate infiltrating monocytes/macrophages from resident microglial cells.

Although the amount of leukocyte infiltration at 4 hours after injury was comparable between wild-type and BLT1-knockout mice (Figure 3E, Figure 5D), we observed a significant suppression of neutrophil infiltration at 12 hours, 1 day, and 3 days after SCI in BLT1-knockout mice. This finding suggests that the cells detected at 4 hours after SCI were more likely due to passive leakage accompanying hemorrhage than to their own chemotactic migration and that the LTB4–BLT1 axis required more than several hours to be have an effect in this traumatic injury model.

Under conditions of blood–brain barrier breakdown, the injured spinal cord is extensively exposed to neurotoxic factors from the peripheral blood. Moreover, infiltrating neutrophils contribute to enhance additional blood–brain barrier breakdown by releasing several critical factors, such as matrix metalloproteinase-9.38,39 Therefore, the modulation of neutrophil infiltration is thought to be a major potential target for the treatment of SCI. Carlson et al3 reported that the number of infiltrating neutrophils significantly correlated with the amount of tissue damage after SCI. Other studies have also reported that suppression of neutrophil infiltration after SCI by administering anti-P-selectin or anti-intercellular adhesion molecule-1 antibody results in amelioration of the secondary injury and improvement of functional recovery.9,40 In addition to these adhesion molecules, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNFα also mediate neutrophil infiltration after SCI.41 A previous report indicated that the delivery of the IL-6/sIL-6R fusion protein to injury sites induced a sixfold increase in neutrophil infiltration and expanded the damaged area.42 Down-regulation of these cytokines by injecting receptor antibodies reduces the number of infiltrating inflammatory cells and reduces neural cell death, leading to improved functional recovery after traumatic central nervous system injury.7,43 In the present study, we fractionated infiltrating neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and resident microglial cells and successfully isolated them from the injured spinal cord to analyze their individual gene expression profiles. Our results demonstrated that these inflammatory cells directly contribute to the dramatic upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines at the lesion area (Figure 4, A–C, see Supplemental Figure S2 available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Further, our evaluation of neural cell viability in co-cultures with circulating neutrophils or activated neutrophils from injured spinal cord of the two genotypes verified that infiltrating neutrophils have a neurotoxic effect. Neurotoxicity as well as the expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines of the activated neutrophils did not significantly differ between genotypes (Figure 4D, see Supplemental Figure S3 available at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Therefore, the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine production and better functional recovery in BLT1 knockout mice after SCI is mainly attributed to the reduction in the neutrophil infiltration, rather than to the degree of neutrophil activation. Based on these findings, LTB4 is a key molecule for inducing an inflammatory reaction through the amplification of neutrophil infiltration as a potent chemoattractant during the acute phase of SCI.

A large amount of research has focused on the neural apoptosis induced by post-traumatic inflammatory reactions after SCI.2 Armstrong et al44 reported that neuronal apoptosis is induced by an inflammatory reaction, and Genovese et al45 reported that anti-inflammatory treatments with etanercept and dexamethasone attenuate the induction of apoptosis after SCI. In particular, Fas, TNFα, and caspase8 play essential roles in apoptotic mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Demjen et al46 showed that functional recovery and axonal regeneration were closely associated with these mediators. These “death receptors” are expressed on oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microglial cells after SCI.47,48 In our study, the number of apoptotic cells and the expression levels of Fas, FasL, and caspase8 were reduced at 12 hours after SCI in BLT1-knockout mice. Considering that BLT1 expression was not observed in adult neural cells in wild-type mice, as shown in Figure 1 and by others,15,49 the decreased proportion of apoptotic cells and the greater white matter sparing in BLT1-knockout mice is likely due to the suppression of neutrophil infiltration. In addition, direct isolation by cell sorting successfully demonstrated that FasL was highly expressed in infiltrating neutrophils in the lesion area. Nesic-Taylor et al50 reported that pro-apoptotic Bax upregulation and anti-apoptotic Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 down-regulation are the most prominent at 12 hours after SCI, which supports our results because the amount of neutrophil infiltration peaked at 12 hours after SCI.

In the present study, BLT1-knockout mice exhibited better functional recovery than wild-type mice. We speculate that this improvement is partly due to the extent of spared myelinated axons, which were more preserved at the lesion area in BLT1-knockout mice. Although oligodendrocytes play an integral role in locomotor function as myelin-forming cells to facilitate saltatory conduction along nerve fibers, they are highly susceptible to pathological conditions such as central nervous system injury and ischemia whereupon they undergo cell death.51,52 After SCI, infiltrating neutrophils are a main source of inflammation and oxidative damage, both of which promote oligodendrocyte death.53 Jurewicz et al54 reported that TNF directly induces oligodendrocyte death mediated by the p55 TNF receptor. We demonstrated that the expression level of TNF,52α is significantly suppressed in BLT1-knockout mice, mainly due to reduced neutrophil infiltration at the lesion area, leading to the prevention of oligodendrocyte loss. Another conceivable mechanism for functional improvement is the remodeling of the relay connections of propriospinal tracts induced by surviving gray matter neurons. As shown in Figure 7, F and G, a smaller number of apoptotic neurons was observed around the injury area in BLT1-knockout mice, as compared with wild-type mice.

Our studies using the LTB4 receptor antagonist suggest a possible therapeutic application for SCI. A significant reduction in neutrophil and monocyte/macrophage infiltration in the ONO-4057 treated mice is considered to account for suppression of the inflammatory reaction at the lesion area and improved functional recovery. Similar findings of suppressed neutrophil infiltration were reported in a glomerulonephritis model treated with ONO-4057.55

Interestingly, complete neutrophil depletion in mice severely impaired functional recovery after SCI, suggesting that the role of infiltrating neutrophils in tissue damage is more complex than that of mere deterioration (unpublished data). Stirling et al56 also reported that neutrophil depletion after SCI alters the production of growth factors and chemokines important for promoting wound healing, resulting in a worse behavioral outcome. Although only minor attention has been paid to the role of infiltrating neutrophils in tissue protection until now, it could be an essential factor for a well-balanced inflammatory reaction under pathological conditions.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study demonstrated the pathophysiologic involvement of the LTB4–BLT1 axis in inflammatory reactions and secondary damage after traumatic injury. The effect of LTB4 as a chemoattractant for neutrophils in SCI is not as dramatic as that in autoimmune diseases because neutrophils leaking from disrupted blood vessels in the lesion area automatically enhance inflammation following SCI.57 Nevertheless, LTB4 does contribute to regulate the inflammatory reaction as an amplification factor for neutrophil infiltration after injury. Moreover, this is the first study to use cell sorting to clarify the detailed cytokine/chemokine expression profile of infiltrating leukocytes and microglial cells, as well as their direct contribution to dramatic up-regulation of the inflammatory reaction. This analytical strategy using flow cytometry will be useful in the field of neuroimmunology, and our results provide a better understanding of the inflammatory machinery after traumatic injury in the central nervous system.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Seiji Okada, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Research Superstar Program Stem Cell Unit, Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, Maidashi, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka, Japan, 812-8582. E-mail: HTseokada@ortho.med.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Supported in parts by Grant-in-aid for Young Scientists, 19689031 from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology for Kyushu University, and research foundations from the general insurance association of Japan, Takeda Science Foundation, Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders, and Japan Orthopaedics and Traumatology foundation (No.0180).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Beattie MS. Inflammation and apoptosis: linked therapeutic targets in spinal cord injury. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:580–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe MJ, Bresnahan JC, Shuman SL, Masters JN, Beattie MS. Apoptosis and delayed degeneration after spinal cord injury in rats and monkeys. Nat Med. 1997;3:73–76. doi: 10.1038/nm0197-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson SL, Parrish ME, Springer JE, Doty K, Dossett L. Acute inflammatory response in spinal cord following impact injury. Exp Neurol. 1998;151:77–88. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie MS, Farooqui AA, Bresnahan JC. Review of current evidence for apoptosis after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:915–925. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JW, Sadowsky C. Spinal-cord injury. Lancet. 2002;359:417–425. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich PG, Jones TB. Manipulating neuroinflammatory reactions in the injured spinal cord: back to basics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:13–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Nakamura M, Mikami Y, Shimazaki T, Mihara M, Ohsugi Y, Iwamoto Y, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, Toyama Y, Okano H. Blockade of interleukin-6 receptor suppresses reactive astrogliosis and ameliorates functional recovery in experimental spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:265–276. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Inflammation and its role in neuroprotection, axonal regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka Y, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Murakami K, Harada N, Johno M, Naruo M. Activated protein C reduces the severity of compression-induced spinal cord injury in rats by inhibiting activation of leukocytes. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1393–1398. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01393.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Genovese T, Mazzon E, Crisafulli C, Di Paola R, Muià C, Esposito E, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S. TNF-alpha blockage in a mouse model of SCI: evidence for improved outcome. Shock. 2008;29:32–41. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318059053a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmblad J, Malmsten CL, Uden AM, Radmark O, Engstedt L, Samuelsson B. Leukotriene B4 is a potent and stereospecific stimulator of neutrophil chemotaxis and adherence. Blood. 1981;58:658–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Hutchinson AW, Bray WM, Doig MV, Shipley ME, Smith MJ. Leukotriene B, a potent chemokinetic and aggregating substance released from polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Nature. 1980;286:264–265. doi: 10.1038/286264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomizo T, Izumi T, Chang K, Takuwa Y, Shimizu T. A G-protein-coupled receptor for leukotriene B4 that mediates chemotaxis. Nature. 1997;387:620–624. doi: 10.1038/42506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuno T, Yokomizo T, Hori T, Miyano M, Shimizu T. Leukotriene B4 receptor and the function of its helix 8. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32049–32052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500007200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jala VR, Haribabu B. Leukotrienes and atherosclerosis: new roles for old mediators. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa A, Hogaboam CM, Lukacs NW, Lincoln PM, Strieter RM, Lunkel SL. Endogenous monocyte chemoattractant protein-1(MCP-1) protects mice in a model of acute septic peritonitis: cross-talk between MCP-1 and leukotriene B4. J Immunol. 1999;163:6148–6154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen SE, Kumlin M, Bjorck T, Raud J, Wikstrom E, Hedgvist P. Lipoxins and other lipoxygenase products with relevance to inflammatory reactions in the lung. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1991;629:262–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb37982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back M, Bu D, Branstrom R, Sheikine Y, Yan ZQ, Hansson GK. Leukotriene B4 signaling through NF-kB-dependent BLT1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis and intimal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17501–17506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505845102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terawaki K, Yokomizo T, Nagase T, Toda A, Taniguchi M, Hashizume K, Yagi T, Shimizu T. Absence of leukotriene B4 receptor 1 confers resistance to airway hyperresponsiveness and Th2-type immune responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:4217–4225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds BA, Tetzlaff W, Weiss S. A multipotent EGF-responsive striatal embryonic progenitor cell produces neurons and astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4565–4574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04565.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka Y, Yokomizo T, Terawaki K, Komine M, Tamaki K, Shimizu T. Characterization of a mouse secondaleukotriene B4 receptor, mBLT2: bLT2-dependent ERK activation and cell migration of primary mouse keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24816–24823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso DM, Fisher LC, Anderson AJ, Jakeman LB, McTigue DM, Popovich PG. Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:635–659. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JA, Hsu CY, Liu TH, Hogan EL, Perot PL, Jr, Tai HH. Leukotriene B4 release and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration in spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 1990;55:907–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KD, Duraiswamy N, Hammerberg C, Allen E, Kimbrough-Green C, Dillon W, Thomas D. Neutrophils, differentiated macrophages, and monocyte/macrophage antigen presenting cells infiltrate murine epidermis after UV injury. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:155–163. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12363639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Huang L, Sung SS, Lobo PI, Brown MG, Gregg RK, Engelhard VH, Okusa MD. NKT cell activation mediates neutrophil IFN-gamma production and renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2007;178:5899–5911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling DP, Yong VW. Dynamics of the inflammatory response after murine spinal cord injury revealed by flow cytometry. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1944–1958. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ND, Chou RC, Seung E, Tager AM, Luster AD. A unique requirement for the leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 for neutrophil recruitment in inflammatory arthritis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:829–835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haribabu B, Verghese MW, Steeber DA, Sellars DD, Bock CB, Snyderman R. Targeted disruption of the leukotriene B4 receptor in mice reveals its role in inflammation and platelet-activating factor-induced anaphylaxis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:433–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson WR, Jr, Lewis DB, Albert RK, Zhang Y, Lamm WJ, Chiang GK, Hones F, Eriksen P, Tien YT, Jonas M, Chi EY. The importance of leukotrienes in airway inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1483–1494. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji F, Oki K, Fujisawa K, Okahara A, Horiuchi M, Mita S. Involvement of leukotriene B4 in arthritis models. Life Sci. 1999;64:L51. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00556-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RJ, Petipher ER, Koch K, Farrel CA, Breslow R, Conklyn MJ, Smith MA, Hackman BC, Wimberly DJ, Milici AJ. Leukotriene B4 plays a critical role in the progression of collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:517–521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager AM, Dufour JH, Goodarzi K, Bercury SD, Andrian UH, Luster AD. BLTR mediates leukotriene B4-induced chemotaxis and adhesion and plays a dominant role in eosinophil accumulation in a murine model of peritonitis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:439–446. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen SE, Bjork J, Hedqvist P, Arfors KE, Hammarstrom S, Lindgren JA, Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes promote plasma leakage and leukocyte adhesion in postcapillary venules: in vivo effects with relevance to the acute inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3887–3891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao F, Atkinson C, Song H, Pannu R, Singh I, Tomlinson S. Complement plays an important role in spinal cord injury and represents a therapeutic target for improving recovery following trauma. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1039–1047. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JC, Norenberg MD, Ramsay DA, Dekaban GA, Marcillo AE, Saenz AD, Pasquale-Styles M, Dietrich WD, Weaver LC. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain. 2006;129:3249–3269. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovich PG, Guan Z, Wei P, Huitinga I, van Rooijen N, Stokes BT. Depletion of hematogenous macrophages promotes partial hindlimb recovery and neuroanatomical repair after experimental spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 1999;158:351–365. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longbrake EE, Lai W, Ankeny DP, Popovich PG. Characterization and modeling of monocyte-derived macrophages after spinal cord injury. J Neurochem. 2007;102:1083–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9451–9462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2674-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosell A, Cuadrado E, Ortega-Aznar A, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Lo EH, Montaner J. MMP-9-positive neutrophil infiltration is associated to blood-brain barrier breakdown and basal lamina type 4 collagen degradation during hemorrhagic transformation after human ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1121–1126. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada Y, Ikata T, Katoh S, Nakauchi K, Niwa M, Kawai Y, Fukuzawa Involvement of an intercellular adhesion molecule 1-dependent pathway in the pathogenesis of secondary changes after spinal cord injury in rats. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1525–1531. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66041525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streit WJ, Semple-Rowland SL, Hurley SD, Miller RC, Popovich PG, Stokes BT. Cytokine mRNA profiles in contused spinal cord and axotomized facial nucleus suggest a beneficial role for inflammation and gliosis. Exp Neurol. 1998;152:74–87. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix S, Chang L, Rose-John S, Tuszynski MH. Delivery of hyper-IL-6 to the injured spinal cord increases neutrophil and macrophage infiltration and inhibits axonal growth. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454:213–228. doi: 10.1002/cne.10407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KT, Wang YW, Wo YY, Yang YL. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated IL-1-induced cortical neuron damage during traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong RC, Aja TJ, Hoang KD, Gaur S, Bai X, Alnemri ES, Litwack G, Karanewsky DS, Fritz LC, Tomaselli KJ. Activation of the CED3/ICE-related protease CPP32 in cerebellar granule neurons undergoing apoptosis but not necrosis. J Neurosci. 1997;17:553–562. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00553.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese T, Mazzon E, Crisafulli C, Esposito E, Di Paola R, Muià C, Di Bella P, Meli R, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S. Combination of dexamethasone and etanercept reduces secondary damage in experimental spinal cord trauma. Neuroscience. 2007;150:168–181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demjen D, Klussmann S, Kleber S, Zuliani C, Stieltjes B, Metzger C, Hirt UA, Walczak H, Falk W, Essig M, Edler L, Krammer PH, Martin-Villalba A. Neutralization of CD95 ligand promotes regeneration and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2004;10:389–395. doi: 10.1038/nm1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casha S, Yu WR, Fehlings MG. Oligodendroglial apoptosis occurs along degenerating axons and is associated with FAS and p75 expression following spinal cord injury in the rat. Neuroscience. 2001;103:203–218. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann ON. Post-traumatic inflammation following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:369–378. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Arita M, Nakajima A, Katayama K, Kudo C, Kamisaki Y, Serhan CN. Leukotriene B4 and lipoxin A4 are regulatory signals for neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation. FASEB J. 2006;20:1785–1792. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5809com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic-Taylor O, Cittelly D, Ye Z, Xu GY, Unabia G, Lee JC, Svrakic NM, Liu XH, Youle RJ, Wood TG, McAdoo D, Westlund KN, Hulsebosch CE, Perez-Polo JR. Exogenous Bcl-XL fusion protein spares neurons after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:628–637. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Hisahara S, Hara H, Yamawaki T, Fukuuchi Y, Yuan J, Okano H, Miura M. Caspases determine the vulnerability of oligodendrocytes in the ischemic brain. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:643–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI10203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Nakamura M, Ogawa Y, Toyama Y, Miura M, Okano H. Targeted expression of anti-apoptotic protein p35 in oligodendrocytes reduces delayed demyelination and functional impairment after spinal cord injury. Glia. 2005;51:312–321. doi: 10.1002/glia.20212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTigue DM, Tripathi RB. The life, death, and replacement of oligodendrocytes in the adult CNS. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurewicz A, Matysiak M, Tybor K, Kilianek L, Raine CS, Selmaj K. Tumour necrosis factor-induced death of adult human oligodendrocytes is mediated by apoptosis inducing factor. Brain. 2005;128:2675–2688. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Tanji M, Takano K, Fukuda Y, Isome M, Nozawa R, Suzuki H, Hosoya M. The leukotriene B4 receptor antagonist ONO-4057 inhibits mesangioproliferative changes in anti-Thy-1 nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:2697–703. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling DP, Liu S, Kubes P, Yong VW. Depletion of Ly6G/Gr-1 leukocytes after spinal cord injury in mice alters wound healing and worsens neurological outcome. J Neurosci. 2009;29:753–764. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4918-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Lam BK, Kanaoka Y, Nigrovic PA, Audoly LP, Austen KF, Lee DM. Neutrophil-derived leukotriene B4 is required for inflammatory arthritis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:837–842. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]