Abstract

The barrier abnormality, a loss-of-function mutation in the gene encoding filaggrin (FLG), which is linked to the incidence of atopic dermatitis (AD), is a recently discovered but important factor in the pathogenesis of AD. Flaky tail (Flgft) mice, essentially deficient in filaggrin, have been used to investigate the role of filaggrin on AD. However, the relevancy of Flgft mice to human AD needs to be determined further. In this study, we observed the clinical manifestations of Flgft mice in the steady state and their cutaneous immune responses against external stimuli, favoring human AD. Under specific pathogen-free conditions, the majority of Flgft mice developed clinical and histological eczematous skin lesions similar to human AD with outside-to-inside skin barrier dysfunction evaluated by newly devised methods. In addition, cutaneous hapten-induced contact hypersensitivity as a model of acquired immune response and a mite extract-induced dermatitis model physiologically relevant to a human AD were enhanced in Flgft mice. These results suggest that the Flgft mouse genotype has potential as an animal model of AD corresponding with filaggrin mutation in human AD.

Atopic dermatitis (AD), which affects at least 15% of children in developed countries, is characterized by eczematous skin lesions, dry skin, and pruritus.1,2,3 Although the precise pathogenic mechanism of AD is as yet unknown, several accumulated lines of evidence suggest that a defective skin barrier to environmental stimuli may contribute to its pathogenesis. It has long been thought that the barrier abnormality in AD is not merely an epiphenomenon but rather is the “driver” of disease activity.4 The evidence for a primary structural abnormality of the stratum corneum in AD is derived from a recently discovered link between the incidence of AD and loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin (FLG). Individuals carrying the FLG null allele variants tend to develop AD.5,6,7

Filaggrin protein is localized in the granular layers of the epidermis. Profilaggrin, a 400-kDa polyprotein, is the main component of keratohyalin granules.8,9,10 In the differentiation of keratinocytes, profilaggrin is dephosphorylated and cleaved into 10 to 12 essentially identical 27-kDa filaggrin molecules, which aggregate in the keratin cytoskeleton system to form a dense protein-lipid matrix.10 This structure is thought to prevent epidermal water loss and impede the entry of external stimuli, such as allergens, toxic chemicals, and infectious organisms. Therefore, filaggrin is a key protein in the terminal differentiation of the epidermis and in skin barrier function.11

Because AD is a common disease for which satisfactory therapies have not yet been established, understanding the mechanism of AD through animal models is an essential issue.1,12 Flaky tail (Flgft) mice, first introduced in 1958, are spontaneously mutated mice with abnormally small ears, tail constriction, and a flaky appearance of the tail skin, which is most evident between 5 and 14 days of age.13 Mice of the Flgft genotype express an abnormal profilaggrin polypeptide that does not form normal keratohyalin F granules and is not proteolytically processed to filaggrin. Therefore, filaggrin is absent from the cornified layers in the epidermis of the Flgft mouse.14,15,16

Recently, it has been revealed that the gene responsible for the characteristic phenotype of Flgft mice is a nonsense mutation of 1-bp deletion analogous to a common human FLG mutation.15 These mice developed eczematous skin lesions after age 28 weeks under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions17 and enhanced penetration of tracer perfusion determined by ultrastructural visualization,16 and were predisposed to develop an allergen-specific immune response after epicutaneous sensitization with the foreign allergen ovalbumin (OVA).15,17 On the other hand, general immunity through intraperitoneal sensitization with OVA was comparable between Flgft mice and control mice.15,17

Despite these recent advances, there still remain several issues with Flgft mice to be addressed. For example, serial close observation of clinical manifestations in reference to human AD will be informative. It is of value to evaluate the responses to external stimuli relevant to human AD, such as mite extracts, instead of OVA that has been used previously. A comparative study on the skin-mediated contact hypersensitivity (CHS) response and non-skin-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity response is important to evaluate the impact of barrier dysfunction on immune responses in vivo. In addition, although it has now been determined that the barrier dysfunction is a key element in the establishment of AD, there is no established method to evaluate the outside-to-inside barrier function quantitatively.

In this study, we found that Flgft mice showed spontaneous dermatitis with skin lesions mimicking human AD in a steady state under SPF conditions: serial occurrence of manifestations as scaling, erythema, pruritus, and erosion followed by edema in this order. We also successfully evaluated outside-to-inside barrier dysfunction in Flgft mice quantitatively using a newly developed method. In addition, we determined that the Th1/Tc1-mediated immune response was enhanced by immunization through skin but not through non-skin immunization. Last, we induced severe AD-like skin lesions in Flgft mice by application of mites as a physiologically relevant antigen for human AD, which will be an applicable animal model of AD.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6NCrSlc (B6) mice were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). Flaky tail (STOCK a/a ma ft/ma ft/J; Flgft mice) mice have double-homozygous filaggrin (Flg) and matted (ma) mutations.13,14 We used B6 mice as a control of Flgft mice because Flgft mice were described to be outcrossed onto B6 mice at The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME)13,14 (of note, although the strain was crossed with B6, it is not a B6 congenic strain but rather a hybrid stock that is probably semi-inbred). Female mice were used in all experiments unless otherwise stated; they were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle at a temperature of 24°C and at a humidity of 50 + 10% under SPF conditions at Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine. Routine colony surveillance and diagnostic workup verified that mice were free of Ectromelia virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, mouse hepatitis virus, Sendai virus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, cilia-associated respiratory bacillus, Citrobacter rodentium [Escherichia coli O115a,c:K(B)], Clostridium piliforme (Tyzzer’s organism), Corynebacterium kutscheri, Helicobacter hepaticus, Pasteurella pneumotropica, Salmonella spp., parasites, intestinal protozoans, Enterobius, and ectoparasites. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine.

Clinical Observation and Histology

The clinical severity of skin lesions was scored according to the macroscopic diagnostic criteria that were used for the NC/Nga mouse.18 In brief, the total clinical score for skin lesions was designated as the sum of individual scores, graded as 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (severe), for the symptoms of pruritus, erythema, edema, erosion, and scaling. Pruritus was observed clinically for more than 2 minutes.

For the histological portion of the study, the dorsal skin of mice was stained with H&E. Toluidine blue staining was used to detect mast cells, and the number of mast cells was calculated as the average from five different fields of each sample ×40 magnification).

Flow Cytometric Analysis and Quantitative RT-PCR

Cells from the skin-draining axillary and inguinal lymph nodes (LNs) and from the spleen were analyzed with flow cytometry. Fluorescent-labeled anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies were obtained from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) and used to stain cells. The total number of cells per organ and the number of cells in each subset were calculated through flow cytometry using the FACSCanto II system (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described previously, using the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a control.19

Total and Mite-Specific Serum IgE

Total serum IgE levels were measured with a mouse IgE ELISA Kit (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. For the measurement of mite-specific IgE levels, the same type of mouse IgE ELISA Kit was used with slightly modifications. Specifically, plates were coated and incubated with 10 μg/ml Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Dp) (Biostir, Kobe, Japan) diluted with coating buffer for 60 minutes. After a blocking period of 30 minutes, 100 μl of 5× diluted serum was added into each well and incubated for 2 hours. Anti-mouse IgE-horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:15,000; 100 μL) was used to conjugate the antigen-antibody complex for 60 minutes at room temperature; from this point on the ELISA Kit was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The difference between the sample absorbance and the mean of negative control absorbance was taken as the result.

Skin Barrier Function

The dorsal regions of the skin were shaved in all mice before measurement. To evaluate inside-to-outside barrier function, transepidermal water loss (TEWL) was measured with a Tewameter Vapo Scan (Asahi Biomed, Tokyo, Japan) at 24°C and 46% relative humidity.

Outside-to-inside barrier function was assessed by means of fluorescein isothiocyanate isomer I (FITC) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The shaved dorsal skin of mice was treated with 100 μl of 1% FITC diluted in acetone and dibutyl phthalate (1:4); 3 hours later, this area was tape-stripped (Scotch tape, 3M, St. Paul, MN) nine times to remove the stratum corneum containing the remnant of FITC. The painted area (1.2 cm × 1.2 cm) was removed, and FITC concentration was measured. Each skin sample was soaked in PBS at 60°C for 10 seconds, after which the dermis and epidermis were separated. The epidermis was soaked in 500 μl of PBS, homogenized, and spun down at 2200 × g. The supernatant was collected, and fluorescence was measured at an excitation wavelength of 535 nm and an emission wavelength of 460 nm using an Arvo SX 1420 counter (Wallac, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The fluorescence value was compared with a standard curve using FITC serial dilutions.

For the evaluation of fluorescence intensities of FITC penetrated into the epidermis, a 1 × 1 cm skin sample was taken after tape stripping, and a 10-μm Tissue-Tek (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan)-embedded section was analyzed using a BZ-9000 Biorevo digital microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan) at the same time exposure.

An in situ dye permeability assay with toluidine blue was performed using embryos at 18 days (littermates). Unfixed, untreated embryos were dehydrated by a 1-minute incubation in an ascending series of methanol (25, 50, 74, and 100%) and rehydrated with the descending same methanol series, washed in PBS, and stained with 0.01% toluidine blue.

Scratching Behavior

Scratching behavior was measured in detail using the Sclaba Real system (Noveltec, Kobe, Japan). Mice were put into the machine 20 minutes before measurement to allow them to adapt to the new environment. Ointment was then applied, and the number and duration of scratching sessions were counted according to the manufacturer’s protocol for 15 minutes.20

Dermatitis Models

For the assessment of irritant contact dermatitis, 20 μl of 0.2 mg/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied to both sides of the ears. Ear thickness change was measured at 1, 3, 12, and 24 hours as well as 5 days after application.

To induce a CHS response, 25 μl of 0.5% 1-fluoro-2.4-dinitrobenzene (DNFB) (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) was painted on the shaved abdomens of mice for sensitization. Five days later, the ears were challenged with 20 μl of 0.2% DNFB, and ear thickness change was measured at 24 and 48 hours after application. Nonsensitized mice were used as a control. A delayed-type hypersensitivity response model was established using OVA (Sigma-Aldrich). Mice were sensitized with 200 μl of 0.5 mg/ml of OVA in complete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) intraperitoneally and challenged 5 days later with an injection of 20 μl of 1 mg/ml of OVA in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Difco Laboratories) into the hind footpads. Footpad thickness was measured before and 24 hours after challenge. Nonsensitized mice were used as a control. Footpad swelling was calculated by (footpad thickness change of sensitized mice) − (footpad thickness change of nonsensitized mice). To induce murine AD-like skin lesions, 40 mg of 0.5% Dp in white petrolatum was topically applied to the ears and upper back twice a week for 8 weeks. Petrolatum without Dp was used as a control. One gram of Dp body product (Biostir) contained 1.78 mg of total protein with 2.47 μg of Dp protein (Der p1). Ear thickness and clinical scores were measured every week. Mite-specific IgE levels, TEWL, and histological appearance of eczematous skin were observed 12 hours after the final application.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Spontaneous Dermatitis of Flgft Mice in the Steady State under SPF Conditions

As described previously,14,15 the expression of the filaggrin monomer was barely detectable by Western blotting in the dorsal skin of Flgft mice compared with that of B6 mice (data not shown). Here, we investigated the clinical manifestations seen in the skin of Flgft mice raised in a steady state under SPF conditions and found that Flgft mice developed spontaneous dermatitis (Figure 1A). The clinical severities of skin lesions, including pruritic activity, erythema, edema, erosion, and scaling, were scored. The total clinical scores of Flgft mice increased with age (Figure 1B). The first manifestations to appear when mice were young were erythema and fine scaling; pruritic activity, erosion, and edema followed later (Figure 1C). In contrast, no cutaneous manifestation was observed in either B6 mice, studied as a control, or heterozygous mice intercrossed with Flgft and B6 mice kept under SPF conditions throughout the experimental period (data not shown). In addition, there was no apparent difference in terms of clinical manifestations between the genders of Flgft mice throughout the period (data not shown).

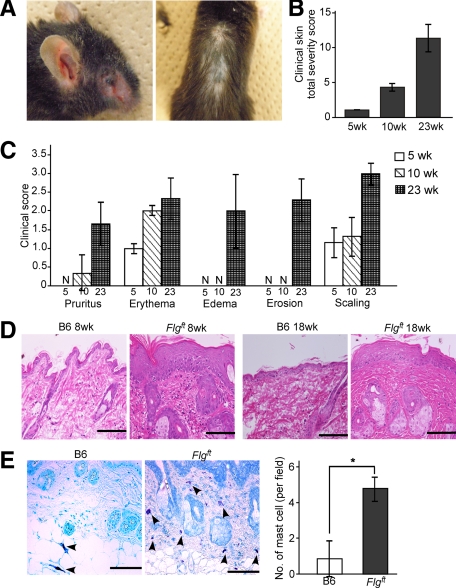

Figure 1.

Spontaneous dermatitis in Flgft mice in SPF. A: Clinical photographs of 20-week-old Flgft mice. Total clinical severity scores (B) for each particular item (C) in 5-, 10- and 23-week-old Flgft mice. N, none. D: H&E-stained sections in 8- and 18-week-old mice. Scale bar = 100 μm. E: Toluidine blue staining of the skin from 8-week-old B6 and Flgft mice and the numbers of mast cells (arrowheads) per field are shown. *P < 0.05.

Histological examination of skin from Flgft mice revealed epidermal acanthosis, increased lymphocyte infiltration, and dense fibrous bundles in the dermis in both younger (8-week-old) and older (18-week-old) Flgft mice; none of these were observed in B6 mice (Figure 1D). In addition, toluidine blue staining to detect mast cells showed an increased number of mast cells, especially degranulated mast cells in the upper dermis, in Flgft mice (Figure 1E). No mouse or human mite bodies were detected in the sections. These data support the diagnosis of spontaneous clinical dermatitis in Flgft mice in the steady state under SPF conditions.

Defect of Skin Barrier Function in Flgft Mice

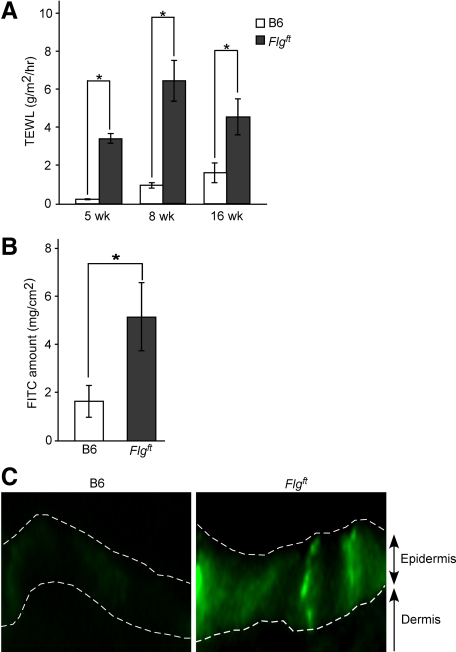

Because barrier dysfunction is a common characteristic of AD,4,5,6,7,21 we measured TEWL, an established indicator of barrier function.21 TEWL was significantly higher in Flgft mice than in B6 mice from an early age (4 weeks) to an older age (16 weeks) (Figure 2A). Because TEWL is only a measure of water transportation through the skin from the inside to the outside of the body, another experimental method was necessary to evaluate outside-to-inside barrier function from the perspective of invasion of external stimuli. To address this issue, we measured FITC penetration through the skin from the outside. FITC solution was applied to the shaved dorsal skin of 8-week-old female mice; 3 hours later, the epidermis was separated and homogenized so that the FITC content could be measured with a fluorometer. The epidermis of Flgft mice contained a higher amount of FITC than that of B6 mice (Figure 2B). Neither group had FITC in the dermis after this procedure, however (data not shown). In addition, observation of fluorescence intensities in the epidermis of both mice showed stronger fluorescence in Flgft mice (Figure 2C). To further analyze the skin permeability, we examined the mouse embryos by toluidine blue solution and showed that the Flgft embryo was entirely dye-permeable compared with the control littermate (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). These data strongly indicate a defect in the skin barrier of Flgft mice, both from inside to outside and from outside to inside.

Figure 2.

Skin barrier dysfunction in Flgft mice. A: TEWL through dorsal skin of 5-, 8-, and 16-week-old B6 and Flgft mice. B: Amount of FITC in the skin of B6 and Flgft mice after topical application. C: Fluorescence intensities of FITC of the skin after topical application. Dashed white lines indicate the border between the epidermis and the dermis, and the top of the epidermis. *P < 0.05.

Immune Status in the Steady State

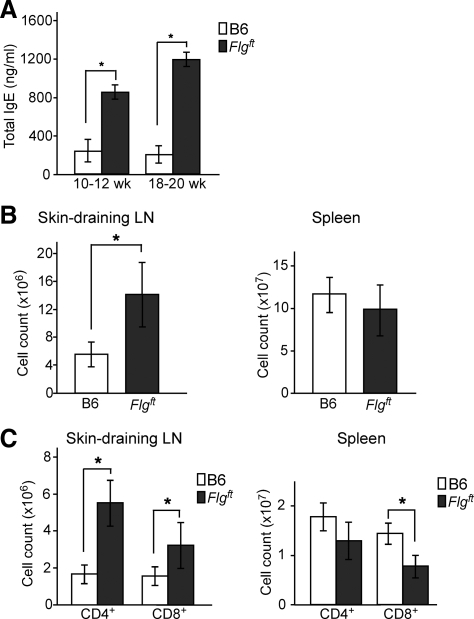

To further elucidate the immune status of Flgft mice in the steady state under SPF conditions, we measured the levels of total serum IgE, because increased severity of AD is known to be correlated with elevated serum IgE levels.22 IgE levels were significantly higher in Flgft mice than in age-matched B6 mice in the steady state under SPF conditions (Figure 3A). To investigate this matter in greater detail, single cell suspensions from the skin-draining inguinal and axillary LNs and from the spleen were analyzed. The total mononuclear cell number of the LNs was significantly higher in Flgft mice than in B6 mice, but that of the spleen was comparable (Figure 3B). In addition, Flgft mice exhibited significantly higher numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in the skin-draining LNs, but not in the spleen (Figure 3C). Thus, an enhanced immune reaction seems to be induced in Flgft mice by the condition of their skin.

Figure 3.

The immune status of Flgft mice in a steady state. A: Total serum IgE levels of B6 and Flgft mice as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. B and C: Numbers of total cells (B), CD4+ cells, and CD8+ cells in the skin-draining LN and spleen (C). *P < 0.05.

To further analyze the immune condition of the skin, we measured the Th1 (interferon-γ [IFN-γ]), Th2 (interleukin [IL]-4 and IL-13), and Th17 (IL-17) cytokine mRNA levels of dorsal skin of 9-week-old mice in the steady state. The mRNA expression levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-13 were similar between Flgft and B6 mice, but there was an enhancement in the IL-17 mRNA expression (data not shown) as reported previously.17

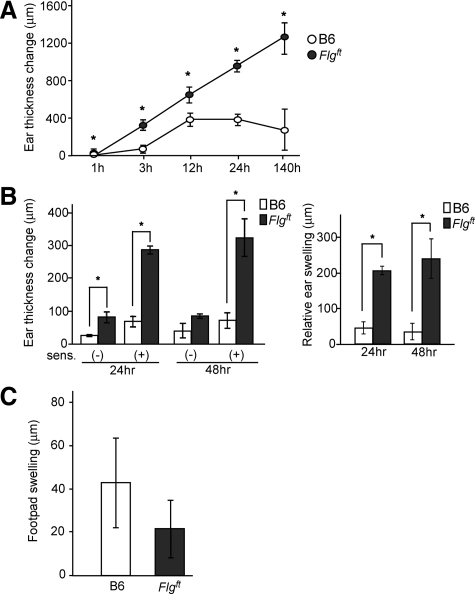

Enhanced Dermatitis in Flgft Mice under External Stimuli

To characterize the likelihood of various cutaneous immune responses, mice were exposed to various external stimuli. First, we studied the irritant contact dermatitis response to PMA as an irritant agent. When we applied PMA to the ears of B6 and Flgft mice, Flgft mice exhibited an enhanced ear swelling response compared with age-matched B6 mice throughout the experimental period (Figure 4A). Next, we measured the CHS response to DNFB. DNFB was applied to the abdominal skin for sensitization; 5 days later, the ears were challenged with the same hapten. The ear thickness change was more prominent in Flgft mice than in B6 mice (Figure 4B, left panel). On the other hand, the ear thickness change of mice without sensitization was higher for Flgft mice than B6 mice, suggesting that irritation contact dermatitis was enhanced in Flgft mice as expected. To avoid the involvement of this irritation in CHS, we next analyzed the relative ear swelling by subtracting the ear thickness change without sensitization from the ear thickness change with sensitization. The relative ear swelling was more extensive in Flgft mice than in B6 mice (Figure 4B, right panel). We then measured the relative amount of mRNA for IFN-γ, as a representative Th1 cytokine, to GAPDH as an endogenous control. The relative amount of IFN-γ was higher in the ears of Flgft mice than in those of B6 mice 12 hours after the challenge (0.27 ± 0.13 versus 0.019 ± 0.013, n = 3). To further assess the immune responses of Flgft mice, we elicited a delayed-type hypersensitivity response through nonepicutaneous sensitization and challenge. Mice were immunized intraperitoneally with OVA and challenged with a subcutaneous injection of OVA into the footpad. In contrast to the CHS response induced via the skin, the resulting footpad swelling in Flgft mice was lower rather than higher than that in B6 mice (Figure 4C). We also examined the production of mRNA levels of the spleen 3 days after intraperitoneal OVA injection, and it showed a similar level of IFN-γ between Flgft mice and B6 mice (relative mRNA amount to GAPDH: 0.011 ± 0.005 versus 0.016 ± 0.006, n = 5). Thus, Th1/Tc1 immune responses were enhanced in Flgft mice only when the stimuli operated via the skin, suggesting that the enhanced immune responses seen in Flgft mice depend on skin barrier dysfunction.

Figure 4.

Enhanced cutaneous immune responses in Flgft mice. A and B: Ear thickness change in B6 and Flgft mice after topical application of PMA as a model of irritant contact dermatitis (A), after DNFB challenge on the ears with or without sensitization (B, left panel) and the relative ear swelling (B, right panel) as a model of CHS. C: Delayed-type hypersensitivity response. B6 and Flgft mice were intraperitoneally sensitized with OVA, and challenged through subcutaneous injection to the footpad. Twenty-four hours later, footpad swelling change was measured. *P < 0.05.

It has been reported that Flgft mice show an enhanced immune response to OVA.15,17 Their reaction to clinically relevant allergens such as mites has not been evaluated, however. It has also been reported that BALB/c or NC/Nga mice develop an allergic cutaneous immune response to mite antigens when they are applied to the skin after vigorous barrier disruption by means of tape-stripping or SDS treatment.23,24 Accordingly, we sought to determine whether skin lesions could be induced in Flgft mice through the application of Dp ointment without any skin barrier disruption procedures to evaluate the physiological significance of filaggrin.

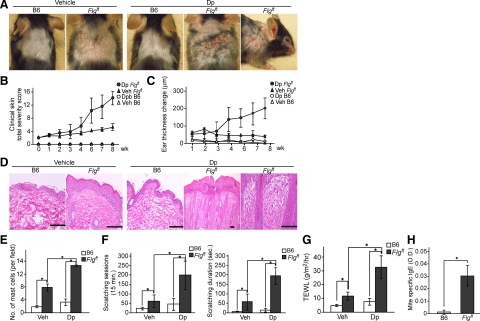

The application of Dp ointment to shaved backs and ears induced no cutaneous manifestation in B6 mice throughout the experimental period (Figure 5, A and B), but the same treatment induced dermatitis in Flgft mice, especially on the ears, face, and dorsal skin. Petrolatum alone, used instead of Dp ointment as a control, induced no skin manifestation (Figure 5, A–C). The clinical severity of Dp-induced dermatitis was scored; after 16 applications of Dp ointment over 8 weeks, Flgft mice had developed a very severe skin condition in contrast with the control groups. Consistently, ear swelling in response to Dp ointment was most prominent in Flgft mice (Figure 5C). Histological examination of H&E-stained sections of involved Flgft skin after 16 applications showed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and dense lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration in the dermis (Figure 5D), accompanied by an increased number of mast cells in the dermis (Figure 5E). We also measured the scratching behavior of Flgft mice treated with Dp using the Sclaba Real system. The number of scratching sessions and the total duration of scratching were significantly higher in Flgft mice than in B6 mice, even among those mice that had not been treated with Dp ointment (Figure 5F); treatment of Flgft mice with Dp ointment raised the number of scratching sessions and the total duration of scratching even higher. We further evaluated barrier function by measuring TEWL in Dp-treated and untreated mice of each genotype; TEWL was higher in untreated Flgft mice than in B6 mice, and Dp treatment of Flgft mice raised TEWL even higher (Figure 5G). Finally, we examined mite-specific serum IgE levels after the last application and found that Flgft mice had higher levels of Dp-specific IgE than B6 mice had (Figure 5H). Thus, the treatment of Flgft mice with Dp ointment, even without prior barrier disruption, remarkably enhanced both the clinical manifestations and the laboratory findings that correspond to indicators of human AD.

Figure 5.

Mite (Dp)-induced dermatitis model. B6 and Flgft mice were topically treated with ointment with (Dp) or without (vehicle/Veh) Dp. A–C: Clinical photographs after the last application of Dp (A), clinical skin severity scores (B), and changes in ear thickness (C) at each indicated time point after application. D and E: Histological appearance of the skin (D) and the numbers of mast cells (E) after the last application. Scale bars = 100 μm. F: Scratching behavior: the number of scratching sessions (left) and the total duration of scratching (right) over 15 minutes after the last application. G: TEWL after the last application. H: Serum mite-specific IgE levels. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrated that Flgft mice exhibit spontaneous dermatitis with lymphadenopathy, elevated IgE levels, and skin barrier disruption in a steady state under SPF conditions. These outcomes are compatible with the features of human AD, which include chronic eczema, pruritus, and dry skin with elevated TEWL and serum IgE levels.1,2,3,4,25,26 In addition, Flgft mice exhibit enhanced susceptibility to irritant contact dermatitis, CHS, and mite-induced dermatitis compared with B6 mice; these characteristics are also reminiscent of human AD. These results suggest that the barrier defect in this strain of mice leads to spontaneous dermatitis and enhances cutaneous immune responses and inflammation.

Since the first introduction of Flgft mice in 1972,13 there have been only a few reports of these mice. The first report demonstrated that Flgft mice without the ma mutation showed flaky skin as early as postnatal day 2 but became normal in appearance by 3 to 4 weeks of age without spontaneous dermatitis except for their slightly smaller ears.13 Later, the lack of filaggrin in the epidermis was proposed in the commercially available strain of Flgft mice used in this study, which has both Flg and ma mutations, as a model of ichthyosis vulgaris, and therefore the cutaneous inflammatory conditions from the perspective of AD was not discussed.14 There have been three recent studies using Flgft mice as a model of filaggrin deficiency: Fallon et al15 used Flgft mice from which the ma mutation had been eliminated with four additional backcrosses to B6 mice, and others used the commercially available Flgft mice.16,17 The first report showed only a histological abnormality without clinical manifestations,15 the second report demonstrated spontaneous eczematous skin lesions after 28 weeks of age,17 and the third report did not indicate any spontaneous dermatitis in Flgft mice.16 In our experiment, we observed a spontaneous dermatitis as early as 5 weeks of age with mild erythema and fine scales. These symptoms gradually exacerbated, accompanied by scratching, erosion, and edema, respectively, and became prominent at the age of 23 weeks. The discrepancies among these results seem to be related to the presence or absence of the ma mutation and/or variation in the genetic backgrounds of the different strains used and to environmental factors. It has been reported that Japan has higher morbidity for AD than other countries,27,28 possibly attributable to environmental factors such as pollen.

It has been reported that TEWL, an indicator of inside-to-outside barrier function, is high in both AD patients with the FLG mutation29 and Flgft mice.15 In consideration of the immunological defense by the skin, however, it is more important to assess outside-to-inside barrier function rather than inside-to-outside barrier function. In fact, outside-to-inside barrier dysfunction has recently been proposed as the most important aspect in the pathogenesis of AD.9,26 Scharschmidt et al16 reported increased bidirectional paracellular permeability of water-soluble xenobiotes by ultrastructural visualization in Flgft mice, suggesting a defect of the outside-to-inside barrier. However, the quantitative measurement of this parameter has not been addressed. Here, we propose a new method for evaluating outside-to-inside barrier function quantitatively by measuring the penetrance of FITC through the skin. This method has a parallel correlation with the qualitative measurement of FITC penetrated in epidermis and an established method for skin permeability assay, the in situ dye staining method. Therefore, by using this new method, we were able to detect outside-to-inside barrier dysfunction in Flgft mice quantitatively.

The skin abnormality associated with AD is well known to be a predisposing factor to sensitive skin30,31 and allergic contact dermatitis,32,33 but patients with AD produce a tuberculin response similar to that of healthy control subjects.34,35 In humans, sensitive skin is defined as reduced tolerance to cutaneous stimulation, with symptoms ranging from visible signs of irritation to subjective neurosensory discomfort.30,31 The question of whether human AD patients are more prone to allergic contact dermatitis than nonatopic individuals is still controversial.33 To address this question, we evaluated skin responsiveness to PMA as an irritant and found that irritant contact dermatitis was enhanced in Flgft mice. In addition, Flgft mice showed an increased skin-sensitized CHS reaction, a form of classic Th1- and Tc1-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity to haptens, emphasized by increased IFN-γ production. In contrast, when mice were sensitized intraperitoneally, no difference was observed between Flgft and B6 mice in vivo or in vitro. This finding is consistent with the observation that humans with and without AD respond comparably to tuberculin tests34,35 and suggests that skin barrier function regulates cutaneous immune conditions, which hints at a possible mechanism involved in human AD.

Clinical studies have provided evidence that a house dust mite allergen plays a causative or exacerbating role in human AD36 and that a strong correlation exists between patients with FLG null alleles and house dust mite-specific IgE.37 AD-like skin lesions can be induced by repeated topical application of a mite allergen in NC/Nga mice but not in BALB/c mice.23 In the present study, we induced skin lesions that were clinically and histologically similar to AD, along with increased TEWL, increased scratch behavior, and increased levels of mite-specific IgE, in Flgft mice through the application of Dp. Dp is a common aeroallergen that is frequently involved in induction of human AD. It has protease activities, specifically from Der p1, Der p3, and Der p9, which may activate protease-activated receptor-2 in human keratinocytes.38,39 A recent report has shown that activation of protease-activated receptor-2 through Dp application significantly delays barrier recovery rate in barrier function-perturbed skin or compromised skin.39 Therefore, Dp may play a dual role in the onset of AD, both as an allergen and proteolytic signal and as a perturbation factor of the barrier function, leading to the persistence of eczematous skin lesions in AD.39,40

To address the issue of variable genetic background, we observed immune responses in mice of other genotypes, such as BALB/c and C3H, as controls, but both of these lines exhibited much less severe CHS responses compared with those in Flgft mice (data not shown), suggesting that the enhanced immune responses seen in Flgft mice were not solely due to their genetic background. The effect of the ma mutation in relation to the ft mutation in commercially available Flgft mice in the development of AD-like skin lesions needs to be clarified in future studies. Furthermore, our study showed that heterozygous mice intercrossed with Flgft mice and B6 mice did not develop spontaneous dermatitis. In this way they are unlike human AD patients, most of whom are heterozygous for the FLG mutation. Not only human studies but also additional mouse studies are required to clarify these relationships.

In this study, we have shown that Flgft mice exhibit spontaneous dermatitis resembling human AD, enhanced irritation dermatitis and a contact hypersensitivity response, and mite-induced AD-like skin lesions, which provide hints for possible mechanisms in the human disease. These results suggest that Flgft mice have the potential to serve as an animal model of human AD and further accentuate the important role of filaggrin in skin barrier function in the pathogenesis of AD.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Kenji Kabashima, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Dermatology and Center for Innovation in Immunoregulative Technology and Therapeutics, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine, 54 Shogoin-Kawara, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan. E-mail: kaba@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Jin H, He R, Oyoshi M, Geha RS. Animal models of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:31–40. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberg A, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis: from the genes to skin lesions. Allergy. 2000;55:205–213. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak N, Bieber T, Leung DY. Immune mechanism leading to atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:S128–S139. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias PM, Hatano Y, Williams ML. Basis for the barrier abnormality in atopic dermatitis: outside-inside-outside pathogenic mechanism. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1337–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer CN, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Zhao Y, Liao H, Lee SP, Goudie DR, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Smith FJ, O'Regan GM, Watson RM, Cecil JE, Bale SJ, Compton JG, DiGiovanna JJ, Fleckman P, Lewis-Jones S, Arseculeratne G, Sergeant A, Munro CS, El Houate B, McElreavey K, Halkjaer LB, Bisgaard H, Mukhopadhyay S, McLean WH. Common loss-of function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–446. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura T, Sandilands A, Akiyama M, Liao H, Evans AT, Sakai K, Ota M, Sugiura H, Yamamoto K, Sato H, Palmer CN, Smith FJ, McLean WH, Shimizu H. Unique mutations in the filaggrin gene in Japanese patients with ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morar N, Cookson WO, Harper JI, Moffat MF. Filaggrin mutations in children with severe atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1667–1672. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale BA. Filaggrin, the matrix protein of keratin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1985;7:65–68. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198502000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listwan P, Rothnagel JA. Keratin bundling proteins. Methods Cell Biol. 2004;78:817–827. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(04)78028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candi E, Schmidt R, Melino G. The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:328–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan SQ, McBride OW, Idler WW, Markova N, Steinert RM. Organization, structure, and polymorphisms of the human profilaggrin gene. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9432–9440. doi: 10.1021/bi00492a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara T, Hayakawa J, Mizukawa Y. Animal models for atopic dermatitis: are they relevant to human disease? J Dermatol Sci. 2004;36:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane P. Two new mutations in linkage group XVI of the house mouse. J Hered. 1972;63:135–140. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a108252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presland RB, Boggess D, Lewis SP, Hull C, Fleckman P, Sundberg JP. Loss of normal profilaggrin and filaggrin in flaky tail (ft/ft) mice: an animal model for the filaggrin-deficient skin disease ichthyosis vulgaris. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1072–1081. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon PG, Sasaki T, Sandilands A, Campbell LE, Saunders SP, Mangan NE, Callanan JJ, Kawasaki H, Shiohama A, Kubo A, Sundberg JP, Presland RB, Fleckman P, Shimizu N, Kudoh J, Irvine AD, Amagai M, McLean WH. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the mouse Flg gene facilitates enhanced percutaneous allergen priming. Nat Genet. 2009;41:602–608. doi: 10.1038/ng.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharschmidt TC, Man MQ, Hatano Y, Crumrine D, Gunathilake R, Sundberg JP, Silva KA, Mauro TM, Hupe M, Cho S, Wu Y, Celli A, Schmuth M, Feingold KR, Elias PM. Filaggrin deficiency confers a paracellular barrier abnormality that reduces inflammatory thresholds to irritants and haptens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:496–506. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.06.046. 506.e1–e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyoshi MK, Murphy GF, Geha RS. Filaggrin-deficient mice exhibit Th17-dominated skin inflammation and permissiveness to epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:475–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.042. 493.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung DY, Hirsch RL, Schneider L, Moody C, Takaoka R, Li SH, Meyerson LA, Mariam SG, Goldstein G, Hanifin JM. Thymopentin therapy reduces the clinical severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;85:927–933. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90079-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Kabashima K, Yoshiki R, Sugita K, Shiraishi N, Onoue A, Kuroda E, Kobayashi M, Yamashita U, Tokura Y. Cutaneous hypersensitivities to hapten are controlled by IFN-γ-upregulated keratinocyte Th1 chemokines and IFN-γ-downregulated Langerhans cell Th2 chemokines. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1719–1727. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orito K, Chida Y, Fujisawa C, Arkwright PD, Matsuda H. A new analytical system for quantification scratching behavior in mice. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta J, Grube E, Ericksen MB, Stevenson MD, Lucky AW, Sheth AP, Assa'ad AH, Khurana Hershey GK. Intrinsically defective skin barrier function in children with atopic dermatitis correlates with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:725–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak N. New insights into the mechanism and management of allergic diseases: atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64:265–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS, Lee K, Han SB, Ahn JM, Lee H, Han MH, Yoon YD, Yoon WK, Park SK, Kim HM. Induction of atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome-like skin lesions by repeated topical application of a crude extract of Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus in NC/Nga mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1616–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Haruna T, Yasui K, Takahashi H, Iduhara M, Takaki S, Deguchi M, Arimura A. A novel atopic dermatitis model induced by topical application with Dermatophagoides farinae extract in NC/Nga mice. Allergol Int. 2007;56:139–148. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.O-06-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Ra C, Kawamoto K, Sato H, Itakura A, Sawada J, Ushio H, Suto H, Mitsuishi K, Hikasa Y, Matsuda H. IgE hyperproduction through enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of Janus kinase 3 in NC/Nga mice, a model for human atopic dermatitis. J Immunol. 1999;162:1056–1063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Hales J, Camp R. IgE-dependent activation of T cells by allergen in atopic dermatitis: pathophysiologic relevance. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:1086–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A, Aït-Khaled N, Anabwani G, Anderson R, Asher I, Beasley R, Bjőrkstėn B, Burr M, Clayton T, Crane J, Ellwood P, Keil U, Lai C, Mallol J, Martinez F, Mitchell E, Montefort S, Pearce N, Shah J, Sibbald B, Strachan D, von Mutius E, Weiland S. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:125–138. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto-Hasebe I, Akiyama M, Nomura T, Sandilands A, McLean WHI, Shimizu H. Clinical severity correlates with impaired barrier in filaggrin-related eczema. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:682–689. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis CM, Shaw S, De Lacharrière O, Baverel M, Reiche L, Jourdain R, Bastien P, Wilkinson JD. Sensitive skin: an epidemiological study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:258–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage MA, Katsarou A, Maibach HI. Sensory, clinical and physiological factors in sensitive skin: a review. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton TH, Wilkinson SM, Rawcliffe C, Pollock B, Clark SM. Allergic contact dermatitis in children: should pattern of dermatitis determine referral? A retrospective study of 500 children tested between 1995 and 2004 in one UK centre. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:114–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailhol C, Lauwers-Cances V, Rance F, Paul C, Giordano-Labadie F. Prevalence and risk factors for allergic contact dermatitis to topical treatment in atopic dermatitis: a study in 641 children. Allergy. 2009;64:801–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz M, Bingöl G, Altintas D, Kendirli SG. Correlation between atopic diseases and tuberculin responses. Allergy. 2000;55:664–667. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüber C, Kulig M, Bergmann R, Guggenmoos-Holzmann I, Wahn U, MAS-90 Study Group Delayed hypersensitivity to tuberculin, total immunoglobulin E, specific sensitization, and atopic manifestation in longitudinally followed early Bacille Calmette-Guėrin-vaccinated and nonvaccinated children. Pediatrics. 2001;107:e36. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Tsuruta S, Yoshida T. Correlation of house dust mite-specific lymphocyte proliferation with IL-5 production, eosinophilia, and the severity of symptoms in infants with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:85–89. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J, Northstone K, Lee SP, Liao H, Zhao Y, Pembrey M, Mukhopadhyay S, Smith GD, Palmer CN, McLean WH, Irvine AD. The burden of disease associated with filaggrin mutations: a population-based, longitudinal birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:872–877. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos Y, Cork MJ, Teare D, Marinou I, Ward SJ, Duff GW, Tazi-Ahnini R. A nonsynonymous substitution of cystatin A, a cysteine protease inhibitor of house dust mite protease, leads to decreased mRNA stability and shows a significant association with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2007;62:514–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SK, Kim HJ, Youm JK, Ahn SK, Choi EH, Sohn MH, Kim KE, Hong JH, Shin DM, Lee SH. Mite and cockroach allergens activate protease-activated receptor 2 and delay epidermal permeability barrier recovery. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1930–1939. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelandt T, Heughebaert C, Hachem JP. Proteolytically active allergens cause barrier breakdown. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1878–1880. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]