Abstract

Recent studies on the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy have focused on correcting adverse biochemical alterations, but there have been fewer efforts to enhance prosurvival pathways. Bcl-2 is the archetypal member of a group of antiapoptotic proteins. In this study, we investigated the ability of overexpressing Bcl-2 in vascular endothelium to protect against early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Transgenic mice overexpressing Bcl-2 regulated by the preproendothelin promoter were generated, resulting in increased endothelial Bcl-2. Diabetes was induced with streptozotocin, and mice were sacrificed at 2 months of study to measure superoxide generation, leukostasis, and immunohistochemistry, and at 7 months to assess retinal histopathology. Diabetes of 2 months duration caused a significant decrease in expression of Bcl-2 in retina, upregulation of Bax in whole retina and isolated retinal microvessels, and increased generation of retinal superoxide and leukostasis. Seven months of diabetes caused a significant increase in the number of degenerate (acellular) capillaries in diabetic animals. Furthermore, overexpression of Bcl-2 in the vascular endothelium inhibited the diabetes-induced degeneration of retinal capillaries and aberrant superoxide generation, but had no effect on Bax expression or leukostasis. Therefore, overexpression of Bcl-2 in endothelial cells inhibits the capillary degeneration that is characteristic of the early stages of diabetic retinopathy, and this effect seems likely to involve inhibition of oxidative stress.

Diabetic retinopathy is characterized in part by accelerated death of capillary cells, leading to vaso-obliteration, nonperfusion, and ultimately, ischemia-mediated neovascularization. Capillary cell death in the retina of diabetic patients and animals also involves apoptotic pathways, with caspases becoming activated in the retina.1 Nonvascular cells of the retina also show evidence of accelerated cell death in diabetes.2,3 The biochemical mechanisms leading to the cell death remain unclear, but multiple studies have implicated oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of the capillary degeneration. Evidence of oxidative stress has been detected in retinas of diabetic animals, and antioxidants inhibit the development of the early stages of the retinopathy in diabetic animals.4,5,6,7,8

Bcl-2 is the archetypal member of a group of anti-apoptotic proteins, although it also inhibits necrotic cell death.9,10,11,12,13,14 In vivo, loss of Bcl-2 expression results in apoptosis,15 and conversely, overexpression of Bcl-2 confers cellular resistance to a wide variety of stimuli for death, including axotomy,16,17,18 retinal degeneration,19 excitotoxicity and calcium overload,20 and hypoxia.13 To explore the consequences of protecting against endothelial death in the early diabetic retinopathy, we created a transgenic mice line selectively expressing Bcl-2 in the vascular endothelium. We then induced diabetes in these mice, using the selective overexpression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 in endothelial cells as a tool for studying the role of endothelial death in the retinal response to diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic Animals

The preproendothelin-1 promoter was used to overexpress Bcl-2 in endothelial cells. This promoter is regarded as relatively specific for endothelial cells,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 but given that endothelin-1 is expressed in astrocytes under some circumstances,28 it also might be activated in retinal glia.

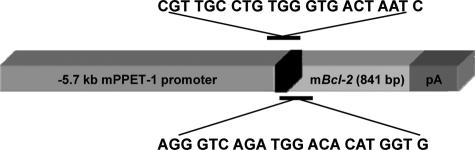

5.7 Kb of the preproendothelin-1 5′ upstream region was cloned into the pGL-3 reporter vector and initially used to transfect cell lines to assess its effectiveness in inducing endothelial cell-specific expression. High levels of expression were seen in a bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cell line but not C6 glioma cells (data not shown). Murine Bcl-2 (gift of S. Korsmeyer (deceased); Washington University, St. Louis, MO) was then cloned into a mammalian expression vector, and sequencing revealed that it was in the correct orientation. The cassette of preproendothelin-1 promoter and Bcl-2 was then cloned, and restriction digests and partial sequencing were used to confirm positioning and accuracy of the junctions. This cassette was excised using HindIII and XhoI, purified on a low-melting point agarose gel and spin-column DNA affinity chromatography, and microinjected into C57BL6/SJL F1 donor eggs through the facilities of the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center Transgenic Facility. Founder mice were screened by Southern blotting and/or PCR of tail DNA using primers specific for a segment spanning the downstream portion of the preproendothelin promoter and the upstream portion of bcl-2 (Figure 1), thus allowing us to differentiate the Bcl-2 introduced into cells from endogenous Bcl-2. Primer sequences for this screening were 5′-AGGGTCAGATGGACACATGGTG- 3′ and 5′-CGTTGCCTGTGGGTGACTAATC-3′. The PCR protocol used was 36 cycles long (95°C - 30 seconds, 58°C - 30 seconds, 72°C - 1 minute). The Bcl-2 transgenic mice produce a 600-bp product that was electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Figure 1.

Schematic of gene and vector used to generate Bcl-2+/? mice.

Two founder mice were positive for the transgene. Based on PCR results, we were not able to determine whether the animals were homozygous or heterozygous for bcl-2, so the transgenic animals were identified as Bcl-2+/?.

Experimental Diabetes

Four experimental groups were generated: nondiabetic wild-type (N), diabetic wild-type (D), nondiabetic overexpressing Bcl-2 in the vascular endothelium (N-bcl-2+/?), and diabetic overexpressing Bcl-2 (D-bcl-2+/?). When the animals were 2 months old, diabetes was induced by intraperitoneal injection of freshly prepared streptozotocin in citrate buffer (pH 4.5; 55 mg/kg of body weight) on 5 successive days into fasted animals. Insulin was given as needed to achieve slow weight gain without preventing hyperglycemia and glucosuria (0 to 0.3 units of long-acting insulin subcutaneously, 0 to 3 times per week). Thus, diabetic animals were insulin-deficient but not catabolic. After induction of diabetes, all animals had free access to food and water and were maintained under a 14 hours on/10 hours off light cycle. Glycated hemoglobin (an estimate of the average level of hyperglycemia over the previous 2 months) was measured by affinity chromatography (Glyc-Affin; Pierce, Rockford, IL) every 2 to 3 months. Food consumption and body weight were measured weekly. Treatment of animals conformed to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Resolution on Treatment of Animals in Research and institutional guidelines.

One group of animals was killed at 2 months of diabetes to measure superoxide generation, leukostasis, and immunohistochemistry. A second group was killed at 7 months of diabetes, and retinal samples used to assess retinal microvascular histopathology.

Isolation of Retinal Vasculature

Retinal blood vessels were isolated from the mouse retina by two techniques. For immunohistochemistry and quantitation of histopathology, the microvascular network was isolated from formalin-fixed retinas by the trypsin digest technique29,30,31,32 and air-dried onto microscope slides. For immunoblots, microvessels were isolated by the osmotic isolation technique33,34,35 and collected in microfuge tubes. Briefly, freshly isolated retina was incubated with distilled water for 1 hour, followed by 3 minutes incubation with DNase (2 mg/ml). The retinal vasculature was then isolated under microscopy by repetitive inspiration and ejection through Pasteur pipettes with sequentially narrower tips. Microvessels isolated by this method showed a normal complement of nuclei and were devoid of gross nonvascular contaminants.

Histopathology

Isolated microvascular preparations dried onto microscope slides were stained with hematoxylin-PAS. Acellular capillaries and pericyte “ghosts“ (the empty pockets in the basement membranes at the sites from which pericytes have disappeared) were counted as previously described.31,36,37,38,39 The number of acellular capillaries was expressed per mm2 of retina, and the number of pericyte ghosts is reported per 1000 capillary cells. All counts of apoptotic cells and histological lesions were performed in a masked fashion.

The number of retinal ganglion cell layer cells in the retina was used to assess neurodegeneration. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded eyes were cut coronally so that the section included both iris and optic nerve or adjacent area. The number of cells in the ganglion cell layer was counted in 0.25-mm lengths of retina on either side of the optic nerve, and the two counts were averaged. The thickness of the inner retina (nerve fiber layer + ganglion cell layer + inner plexiform layer) was measured at 5 random sites in the mid-retina and averaged.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections of paraffin-embedded retinas and isolated retinal microvasculature were subjected to high temperature antigen retrieval in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer, pH 6.0 for 18 minutes. Slides were rinsed in PBS, blocked with Mouse on Mouse (M.O.M.) Immunoglobulin Blocking Solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and reacted with mouse anti-human Bcl-2 (1:50 dilution; BD Transduction Laboratories, BD Biosciences Pharmingen) for 16 to 20 hours at room temperature. Sections were washed, and reacted with M.O.M. biotinylated anti-mouse Ig reagent (1:250), followed by M.O.M. ABC reagent. Color was developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as substrate, followed by nickel enhancement.

Immunoblotting

Bcl-2 and Bax were quantitated in intact retinas and in the isolated retinal microvasculature. Because the isolated retinal vasculature of mice contained so little protein, isolated vessels from six eyes were pooled together for each lane. Samples were homogenized in buffer containing protease inhibitors (leupeptin 1 mg/ml; aprotinin 1 mg/ml), and 50 μg of protein from each sample were loaded on 8% PAGE-SDS and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% nonfat dry milk and incubated with anti–Bcl-2 monoclonal antibody (1:100 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-Bax monoclonal antibody clone 6A7 (1:250 dilution; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were washed and incubated with anti-mouse IgG antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Bio-Rad) at a dilution of l:3000 for another hour. After another extensive washing, protein bands detected by the antibodies were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham, USA) and evaluated by densitometry (Molecular Dynamics, USA). Prestained protein markers (Bio-Rad) were used for molecular mass determinations. To ensure equal loading among lanes, membranes were stained with Ponceau S (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) before immunostaining and poststained with mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Protein concentration of tissue and/or cell lysates were measured by the Bradford procedure using the protein dye regent from Bio-Rad Laboratories and BSA as a standard.

Analysis of Leukostasis

Animals were perfused with intracardiac PBS under anesthesia (ketamine:xylazine = 80 and 20 mg/kg, respectively). Animals then were perfused with fluorescein-coupled concanavalin A lectin (20 μg/ml in PBS; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as described previously.35,39,40 Flat-mounted retinas were imaged via fluorescence microscopy, and the number of leukocytes adherent to the vascular wall per retina was determined by masked counters.

Assessment of Superoxide Anion Production

Lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium nitrate), an acridylium dinitrate compound that emits light on reduction and interaction with the superoxide anion, was used to measure superoxide anion production as previously described.7,39 Previous studies demonstrated that the diabetes-induced increase in lucigenin-dependent retinal luminescence can be eliminated by the superoxide scavenger Tiron and therefore is detecting predominantly superoxide.

Statistical Analysis

Data were summarized as mean ± SD. Experimental groups were compared with the analysis of variance followed by Fisher multiple comparison test.

Results

Expression of Bcl-2 Transgene

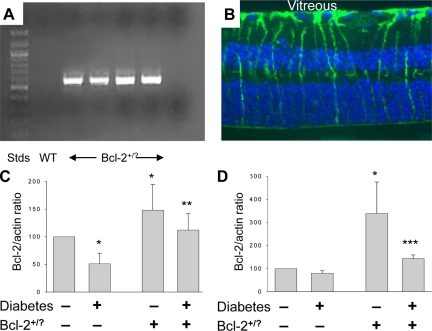

Animals overexpressing Bcl-2 in the vascular endothelium were generated by introducing a transgene carrying murine bcl-2 genomic DNA under the control of the murine preproendothelin promoter into fertilized ova of C57BL/6J mice (Figure 1). RT-PCR analysis with primers that spanned both the downstream portion of the preproendothelin promoter and the upstream portion of bcl-2 revealed active transcription of the transgene in retinas (Figure 2A) and isolated retinal microvasculature (not shown) of transgenic animals, but not in controls. Immunohistochemical examination of retinal sections from N-Bcl-2+/? animals showed little difference from that in wild-type animals and demonstrated that the major site of Bcl-2 expression still was in Müller cells (Figure 2B). Immunoblots of extracts from whole retinas demonstrated that Bcl-2 protein was increased above wild-type by 48 ± 47% in nondiabetic transgenic animals (Figure 2C; P < 0.05). Because microvessels are very difficult to see in cross-sections, we assessed the success of the Bcl-2 overexpression using isolated retinal microvessels. Expression of Bcl-2 was found to be significantly increased (by 339 ± 136%) in retinal microvessels isolated from the N-Bcl-2+/? transgenic animals compared with wild-type nondiabetic animals (Figure 2D; P < 0.05). Immunohistochemistry of isolated retinal microvessels from the transgenic animals revealed punctate immunostaining for Bcl-2 in cytoplasm of capillary endothelial cells (not shown), consistent with the reported localization of Bcl-2 to mitochondria. Similar findings have been reported previously.41 Immunostaining in the transgenic animals was not detected in pericytes or any neural cells, and expression seemed not to be increased in glial cell types.

Figure 2.

Expression of Bcl-2 transgene in retinas from Bcl-2+/? mice. PCR analysis of genomic DNA with murine bcl-2-transgene-specific primers revealed transgene in transgenic animals, but not in controls (A). The major site of Bcl-2 expression in wild-type (not shown) and bcl-2 transgenics (B) was in Müller cells. Immunoblotting showed that Bcl-2+/? transgenic animals expressed greater-than-normal amounts of Bcl-2 protein in retina (C) and isolated retinal blood vessels (D). Results of immunoblots are expressed as a ratio to actin in the same sample and are summarized as percentage of values in wild-type nondiabetic animals. P < 0.05 compared with *wild-type nondiabetic, **wild-type diabetic, and ***diabetic Bcl-2+/?. n = 4 to 7 per group.

Effect of Diabetes on Expression of Bcl-2 in Retina and Retinal Microvessels

Both wild-type and transgenic animals injected with streptozotocin became hyperglycemic and failed to gain body mass at the normal rate (Table 1). In retinas of wild-type rats diabetic for 2 months, expression of Bcl-2 protein was significantly decreased by almost half compared with tissue from wild-type nondiabetic animals (Figure 2B; P < 0.05). In contrast, diabetes had less effect on the amount of Bcl-2 detected in isolated retinal microvessels from wild-type animals (Figure 2D). In Bcl-2+/?mice, diabetes caused a 24 ± 30% decrease in Bcl-2 in whole retina and a 57 ± 5% decrease in Bcl-2 in isolated retinal vessels (both P < 0.05). The end result was that Bcl-2 expression in diabetic Bcl-2+/? transgenic animals was preserved at levels comparable with or greater than those seen in wild-type animals.

Table 1.

Severity of Diabetes in Wild-Type and Transgenic Mice

| Group | Blood glucose (mg/ml) | GHb (%) | Body wt (final; g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (wild-type) | 149 ± 22 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 47 ± 5 |

| D (wild-type) | 347 ± 38 | 14.1 ± 3.9 | 25 ± 5 |

| N Bcl-2+/? | 134 ± 27 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 44 ± 7 |

| D Bcl-2+/? | 347 ± 88 | 12.5 ± 3.6 | 25 ± 5 |

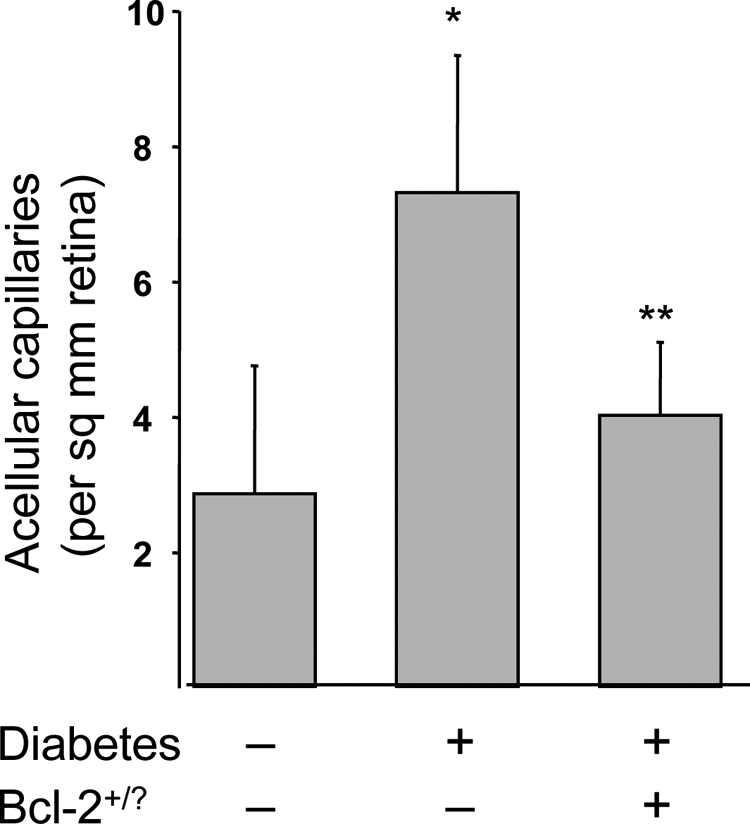

Mice Overexpressing Bcl-2 in Endothelial Cells Are Protected from Diabetes-Induced Degeneration of Retinal Capillaries

Mice were killed after 7 months of diabetes to assess retinal histopathology. As expected, diabetes caused a significant increase in the number of degenerate (acellular) capillaries in wild-type diabetic animals. This capillary degeneration was significantly (P < 0.05) inhibited in animals overexpressing Bcl-2 in the vascular endothelium (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diabetes of 7 months duration significantly increased degeneration of retinal capillaries, and overexpression of Bcl-2 in endothelial cells inhibited this degeneration. n = 7 in all groups. *P < 0.05 compared with wild-type nondiabetic (N). **P < 0.05 compared with D-Bcl-2+/?.

Nonvascular retinal cells die in diabetic rats and humans,42,43,44,45 but results in mice are controversial.45,46,47,48 We therefore studied our animals to re-evaluate the effect of diabetes on retinal neurodegeneration, and if detectable, to assess the effect of endothelium-selective expression of Bcl-2 on this abnormality. Diabetes of 7 months duration did not cause a significant decrease in the number of cells in the ganglion cell layer (27.9 ± 4.4 cells per 250 μm retina length in wild-type diabetic animals versus 26.7 ± 6.5 in wild-type nondiabetic animals; not significant) or thickness of the inner retina (63.9 ± 11.9 μm versus 69.4 ± 8.4; not significant) of wild-type animals. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in endothelium of diabetic animals did not significantly affect ganglion cell layer cell counts or thickness (28.0 ± 7.0 cells per 250 μm retina length; 68.3 ± 11.2 μm).

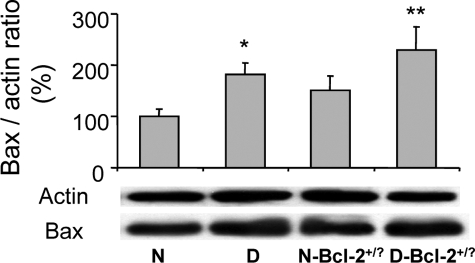

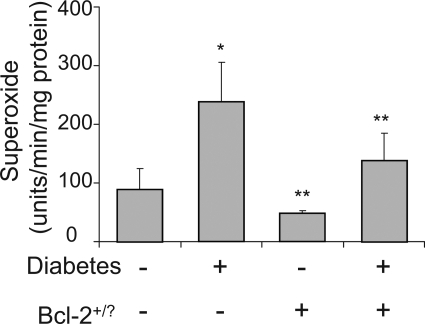

Bax Expression, Leukostasis, and Superoxide Generation

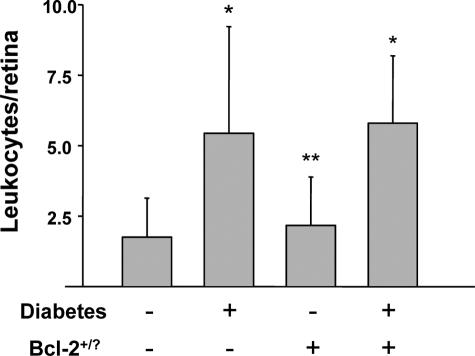

To determine how Bcl-2 overexpression in endothelium inhibited the diabetes-induced death of retinal capillary cells, we investigated several abnormalities that have been postulated to contribute to the development of diabetic retinopathy. In wild-type mice, diabetes significantly increased expression of Bax (expressed as Bax/actin ratio) in retina (160 ± 35% of that in nondiabetic controls; not shown; P < 0.05) and in retinal microvessels (182 ± 22% of that in nondiabetic controls; Figure 4; P < 0.05). Diabetes also increased retinal generation of superoxide (P < 0.0001; Figure 5) and the number of leukocytes adherent to the luminal wall of the retinal microcirculation (P < 0.01; Figure 6). Overexpression of Bcl-2 within the endothelium inhibited the increase in superoxide generation (P < 0.0001) but had no significant effect on the diabetes-induced increase in leukostasis or expression of Bax in isolated retinal blood vessels.

Figure 4.

Bax expression in isolated retinal microvessels of diabetic mice and mice overexpressing Bcl-2 in endothelial cells. *P < 0.05 compared with wild-type nondiabetic (N). n = 4 to 7 per group.

Figure 5.

Generation of superoxide by retina is increased by diabetes of 2 months duration and inhibited by overexpression of Bcl-2. *P < 0.05 compared with appropriate nondiabetic control; **P < 0.05 compared with diabetic control. n = 6 per group.

Figure 6.

Diabetes (2 months duration) results in increased adherence of leukocytes to retinal vasculature, and overexpression of Bcl-2 in endothelium had no effect on this abnormality. *P < 0.05 compared with appropriate nondiabetic control; **P < 0.05 compared with appropriate diabetic control. n = 6 to 7 per group.

Discussion

Degeneration of retinal capillaries begins early in the etiology of diabetic retinopathy and is believed to play a critical role in the progression to the advanced stages of the retinal disease. This diabetes-induced capillary degeneration develops in multiple species, including mice. We show that vascular protection by overexpression of Bcl-2 in vascular endothelial cells significantly inhibited diabetes-induced degeneration of retinal capillaries and generation of superoxide by the retina but did not prevent the increase in leukostasis. Thus, superoxide production and degeneration of retinal microvessels are closely associated in this model, and both can be inhibited by protecting the endothelium via Bcl-2 overexpression in endothelial cells.

Bcl-2 has been used to prevent lesions caused by cell death in a variety of disorders. Evidence for a prosurvival role of Bcl-2 in traumatic brain injury was also demonstrated by the attenuation of posttraumatic cortical neurodegeneration in transgenic mice overexpressing the protein.49,50,51 Bcl-2 overexpression has been found to inhibit photoreceptor degeneration in the eye,19,52 and retinal neurons overexpressing Bcl-2 are protected against axotomy-induced cell death.18,53 Bcl-2 expression in PC-12 cells has been shown to inhibit oxidative stress–induced cell death.54,55,56,57 Bcl-2 is modestly expressed in the normal retina,58 but its expression is altered in retina or brain by a variety of stresses, including axotomy, ischemia, epilepsy, excitotoxic injury, or exposure to damaging levels of light.59,60,61,62,63

Antiapoptotic actions of Bcl-2 occur in part at the mitochondrial membrane by altering the mitochondrial function via permeability transition pores and release of cytochrome c to the cytosol64,65 and are regulated in part by the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax. Consequently, Bcl-2 inhibits mitochondria-mediated cell death66 and ischemia-induced cell death.67 Other reported actions of Bcl-2 include anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of NF-κB in endothelial cells,68 increasing concentrations of reduced glutathione,69,70,71 increasing antioxidant defense status and proteosomal activity,70 and inhibition of phospholipase A2 activation.72,73 Possible molecular mechanisms for cellular protection include effects on intracellular calcium regulation, reactive oxygen species production, caspase activation, and mitochondrial permeability transition.54,55,74,75,76

Unlike the present findings of a diabetes-induced decrease in retinal Bcl-2 in wild-type mice, studies of postmortem human retinas from diabetic subjects showed either no change77 or an increase78 in Bcl-2 expression by immunohistochemistry or immunoblotting, compared with controls. It seems possible that the reported differences between mice and humans with respect to effects of diabetes on expression of Bcl-2 in retina might reflect an adaptation to long-standing diabetes in patients (as opposed to only months of diabetes in the mice) or species differences. The diabetes-induced decrease in Bcl-2 expression in our study was likely attributable to changes within retinal Muller (glial) cells, because Bcl-2 expression has been reported to be highest in the ganglion cell and inner nuclear layers59,79 and especially in endfeet and radial processes of Müller cells in the normal mouse retina.80,81

Using immunoblots of pooled samples of purified retinal microvessels from wild-type animals, we found that Bcl-2 expression was modest but detectable in isolated retinal blood vessels and that its expression was not significantly reduced (20%) in diabetes. Surprisingly, diabetes caused a much larger reduction in Bcl-2 expression in isolated retinal vessels from the transgenic animals. This apparent difference in response to diabetes might be caused by unexpected effects of diabetes on the preproendothelin promoter used to overexpress Bcl-2 in the transgenic animals or by the very small amount of Bcl-2 in vessels from the wild-type animals. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that the increased Bcl-2 expression in retinas from our transgenic animals reflected changes in endothelial cells (as opposed to other retinal cell types). It is important to note that we do not attribute the histopathology of diabetic retinopathy to a reduction in Bcl-2 expression, but rather that therapeutic overexpression of the antiapoptotic protein in endothelial cells inhibited the pathology.

Overexpression of Bcl-2 in cultured cells has been reported to inhibit lipid peroxidation and formation of advanced glycation endproducts82 and nitrotyrosine70 induced by increased glucose concentration, but not to inhibit generation of reactive oxygen species. Thus, it is surprising that endothelial-specific overexpression of Bcl-2 dramatically inhibited the diabetes-induced increase in retinal superoxide production in our in vivo studies. Both retinal cells and white blood cells from diabetic animals are known to generate superoxide.7,83,84,85,86 Although overexpression of Bcl-2 in endothelial cells inhibited retinal superoxide generation in our studies, it seems unlikely that this superoxide generation was solely attributable to the relatively small number of endothelial cells in the retina. It is possible that Bcl-2–mediated protection of the capillary cells might have indirectly exerted a beneficial effect also surrounding retinal or circulating blood cells. The superoxide generation by retinas from wild-type diabetic animals seems unlikely to have been mediated by adherent white blood cells, however, because inhibition of the superoxide generation by Bcl-2 overexpression had no beneficial effect on adherence of the blood cells to the vascular endothelium, a process which is closely associated with respiratory burst and generation of superoxide. Inhibition of 5-lipoxygenase also has been found to inhibit both the diabetes-induced degeneration of retinal capillaries and retinal generation of superoxide, while having no effect on leukostasis.87 These studies suggest that generation of superoxide is more closely associated with capillary degeneration in diabetes than is excessive leukostasis. The present studies do not allow us to rule out possible effects of the Bcl-2 overexpression on a possible contribution of AGEs or lipid peroxides to development of the retinopathy.

The proapoptotic mitochondrial protein, Bax, is increased in retinas88 and retinal mitochondria89 of diabetic animals and is increased also in retinal capillary pericytes in diabetic humans.90 Interestingly, the vascular protection mediated by Bcl-2 overexpression in endothelium occurred despite continued upregulation of the proapoptotic Bax in the vasculature.

Consistent with findings of some45,48 but not all47,91 prior studies, diabetes was not found by us to have had any effect on the number of cells in the ganglion cell layer. These studies thus do not offer support to a hypothesis that ganglion cells play a role in capillary degeneration in diabetes.43 Nevertheless, overexpression of Bcl-2 in endothelial cells clearly inhibits the diabetes-induced vascular histopathology that characterizes the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Boosting survival pathways such as those mediated by Bcl-2 is a novel therapeutic target to inhibit the development of at least the vascular lesions of diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

Breeding and genotyping was conducted in the CWRU Visual Science Research Center core facility (P30EY11373) by Heather Butler and Carol Luckey.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Timothy S. Kern, Ph.D., Center for Diabetes Research, Department of Medicine, 434 Biomedical Research Building, Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44106. E-mail: tsk@case.edu.

Supported by a grant from the American Diabetes Association (to T.K., L.A.L.), by PHS grants EY00300 and DK57733 (to T.K.), the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veteran Affairs (to T.K.), and Research to Prevent Blindness (L.A.L.).

Current address for C.M.M.: Alcon Research Ltd., Health Science Center, University of North Texas, Ft. Worth, TX.

References

- Mohr S, Tang J, Kern TS. Caspase activation in retinas of diabetic and galactosemic mice and diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2002;51:1172–1179. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning X, Baoyu Q, Yuzhen L, Shuli S, Reed E, Li QQ. Neuro-optic cell apoptosis and microangiopathy in KKAY mouse retina. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13:87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki M, Tanaka T, Nawa H, Usui T, Fukuchi T, Ikeda K, Abe H, Takei N. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in early retinal neuropathy of streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats: therapeutic potential of brain-derived neurotrophic factor for dopaminergic amacrine cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:2412–2419. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Kern TS, Engerman RL. Abnormalities of retinal metabolism in diabetes or experimental galactosemia. IV. Antioxidant defense system. Free Radicals Biol Med. 1996;22:587–592. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Tang J, Kern TS. Abnormalities of retinal metabolism in diabetes and experimental galactosemia. VII. Effect of long-term administration of antioxidants on the development of retinopathy. Diabetes. 2001;50:1938–1942. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Brownlee M. The missing link: a single unifying mechanism for diabetic complications. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;77:S26–S30. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Miller CM, Kern TS. Hyperglycemia increases mitochondrial superoxide in retina and retinal cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:1491–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar M, Chan PS, Kern TS, Kowluru RA. Oxidative damage in the retinal mitochondria of diabetic mice: possible protection by superoxide dismutase. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3805–3811. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidarelli A, Cerioni L, Tommasini I, Fiorani M, Brune B, Cantoni O. Role of Bcl-2 in the arachidonate-mediated survival signaling preventing mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent U937 cell necrosis induced by peroxynitrite. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:1638–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbu A, Welsh N, Saldeen J. Cytokine-induced apoptosis and necrosis are preceded by disruption of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Deltapsi(m)) in pancreatic RINm5F cells: prevention by Bcl-2. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;190:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldeen J. Cytokines induce both necrosis and apoptosis via a common Bcl-2-inhibitable pathway in rat insulin-producing cells. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2003–2010. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Yamamoto M. Acquisition of resistance to apoptosis and necrosis by Bcl-xL over-expression in rat hepatoma McA-RH8994 cells. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:682–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamabe K, Shimizu S, Kamiike W, Waguri S, Eguchi Y, Hasegawa J, Okuno S, Yoshioka Y, Ito T, Sawa Y, Uchiyama Y, Tsujimoto Y, Matsuda H. Prevention of hypoxic liver cell necrosis by in vivo human bcl-2 gene transfection. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:217–223. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S, Eguchi Y, Kamiike W, Matsuda H. Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL block apoptosis as well as necrosis: possible involvement of common mediators in apoptotic and necrotic signal transduction pathways. Leukemia. 1997;11 Suppl 3:380–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidis TM, Sendtner M, Cooper JD, Airaksinen MS, Holtmann B, Meyer M, Thoenen H. Inactivation of bcl-2 results in progressive degeneration of motoneurons, sympathetic and sensory neurons during early postnatal development. Neuron. 1996;17:75–89. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlie PG, Dringen R, Rees SM, Kannourakis G, Bernard O. bcl-2 transgene expression can protect neurons against developmental and induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4397–4401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois-Dauphin M, Frankowski H, Tsujimoto Y, Huarte J, Martinou JC. Neonatal motoneurons overexpressing the bcl-2 protooncogene in transgenic mice are protected from axotomy-induced cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3309–3313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti L, Strettoi E, Chierzi S, Cenni MC, Liu XH, Martinou JC, Maffei L, Rabacchi SA. Protection of retinal ganglion cells from natural and axotomy-induced cell death in neonatal transgenic mice overexpressing bcl-2. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4186–4194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04186.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Flannery JG, LaVail MM, Steinberg RH, Xu J, Simon MI. bcl-2 overexpression reduces apoptotic photoreceptor cell death in three different retinal degenerations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7042–7047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins. Oncogene. 1998;17:3225–3236. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harats D, Kurihara H, Belloni H, Ziober A, Ackley D, Cain G, Kurihara Y, Lawn R, Sigal E. Targeting gene expression to the vascular wall in transgenic mice using the murine preproendothelin-1 promoter. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1335–1344. doi: 10.1172/JCI117784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung JW, Ho MC, Lo AC, Chung SS, Chung SK. Endothelial cell-specific over-expression of endothelin- 1 leads to more severe cerebral damage following transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2004;44 Suppl 1:S293–S300. doi: 10.1097/01.fjc.0000166277.70538.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri F, Virdis A, Neves MF, Iglarz M, Seidah NG, Touyz RM, Reudelhuber TL, Schiffrin EL. Endothelium-restricted overexpression of human endothelin-1 causes vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110:2233–2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000144462.08345.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Sanz S, Heggestad AD, Antharam V, Notterpek L, Fletcher BS. Endothelial targeting of the Sleeping Beauty transposon within lung. Mol Ther. 2004;10:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afek A, Zurgil N, Bar-Dayan Y, Polak-Charcon S, Goldberg I, Deutsch M, Kopolovich J, Keren G, Harats D, George J. Overexpression of 15-lipoxygenase in the vascular endothelium is associated with increased thymic apoptosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Pathobiology. 2004;71:261–266. doi: 10.1159/000080060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo T, Kurihara H, Maemura K, Kurihara Y, Kuwaki T, Izumida T, Minamino N, Ju KH, Morita H, Oh-hashi Y, Kumada M, Kangawa K, Nagai R, Yazaki Y. Hypotension and resistance to lipopolysaccharide-induced shock in transgenic mice overexpressing adrenomedullin in their vasculature. Circulation. 2000;101:2309–2316. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.19.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SH, Hui CC, Cheah AY, You XM, Husain M, Rabinovitch M. Targeted overexpression of elafin protects mice against cardiac dysfunction and mortality following viral myocarditis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1211–1219. doi: 10.1172/JCI5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripodas A, de Juan JA, Roldan-Pallares M, Bernal R, Moya J, Chao M, Lopez A, Fernandez-Cruz A, Fernandez-Durango R. Localisation of endothelin-1 mRNA expression and immunoreactivity in the retina and optic nerve from human and porcine eye. Evidence for endothelin-1 expression in astrocytes. Brain Res. 2001;912:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02731-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern TS, Engerman RL. A mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:986–990. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140194013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Engerman RL, Kern TS. Diabetes-induced metabolic abnormalities in myocardium: effect of antioxidant therapy. Free Radic Res. 2000;32:67–74. doi: 10.1080/10715760000300071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern TS, Engerman RL. Pharmacologic inhibition of diabetic retinopathy: aminoguanidine and aspirin. Diabetes. 2001;50:1636–1642. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.7.1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Mohr S, Du Y, Kern TS. Non-uniform distribution of lesions and biochemical abnormalities within the retina of diabetic humans. Curr Eye Res. 2003;27:7–13. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.27.2.7.15455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Jirousek MR, Stramm LE, Farid NA, Engerman RL, Kern TS. Abnormalities of retinal metabolism in diabetes or experimental galactosemia. V. Relationship between protein kinase C and ATPases. Diabetes. 1998;47:464–469. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr GA, Tang J, Ismail-Beigi F, Kern TS. Diabetes down-regulates Glut1 expression in retina and its microvessels, but not in cerebral cortex or its microvessels. Diabetes. 2000;49:1016–1021. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Szabo C, Kern TS. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase is involved in the development of diabetic retinopathy via regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Diabetes. 2004;53:2960–2967. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern TS, Engerman RL. Comparison of retinal lesions in alloxan-diabetic rats and galactose-fed rats. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13:863–867. doi: 10.3109/02713689409015087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern TS, Engerman RE. Animal model of human disease: a mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Comp Pathol Bull. 1997;39:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Engerman RL, Kern TS. Abnormalities of retinal metabolism in diabetes or experimental galactosemia VIII. Prevention by aminoguanidine. Curr Eye Res. 2000;21:814–819. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.21.4.814.5545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Du Y, Miller C, Gubitosi-Klug RA, Ball S, Berkowitz BA, Kern TS. Critical role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in degeneration of retinal capillaries in mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1987–1996. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussen AM, Poulaki V, Le ML, Koizumi K, Esser C, Janicki H, Schraermeyer U, Kociok N, Fauser S, Kirchhof B, Kern TS, Adamis AP. A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J. 2004;18:1450–1452. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1476fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latti S, Leskinen M, Shiota N, Wang Y, Kovanen PT, Lindstedt KA. Mast cell-mediated apoptosis of endothelial cells in vitro: a paracrine mechanism involving TNF-alpha-mediated down-regulation of bcl-2 expression. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:130–138. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sima AA, Zhang WX, Cherian PV, Chakrabarti S. Impaired visual evoked potential and primary axonopathy of the optic nerve in the diabetic BB/W-rat. Diabetologia. 1992;35:602–607. doi: 10.1007/BF00400249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber AJ, Lieth E, Khin SA, Antonetti DA, Buchanan AG, Gardner TW. Neural apoptosis in the retina during experimental and human diabetes. Early onset and effect of insulin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:783–791. doi: 10.1172/JCI2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizu Y, Oyanagi K, Hu J, Nakagawa H. Degeneration of retinal neuronal processes and pigment epithelium in the early stage of the streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Neuropathology. 2002;22:161–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2002.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asnaghi V, Gerhardinger C, Hoehn T, Adeboje A, Lorenzi M. A role for the polyol pathway in the early neuroretinal apoptosis and glial changes induced by diabetes in the rat. Diabetes. 2003;52:506–511. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusner LL, Sarthy VP, Mohr S. Nuclear translocation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: a role in high glucose-induced apoptosis in retinal Muller cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1553–1561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PM, Roon P, Van Ells TK, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Death of retinal neurons in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3330–3336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feit-Leichman RA, Kinouchi R, Takeda M, Fan Z, Mohr S, Kern TS, Chen DF. Vascular Damage in a Mouse Model of Diabetic Retinopathy: relation to Neuronal and Glial Changes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4281–4287. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake H, Hanada N, Nakamura H, Kagawa S, Fujiwara T, Hara I, Eto H, Gohji K, Arakawa S, Kamidono S, Saya H. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in bladder cancer cells inhibits apoptosis induced by cisplatin and adenoviral-mediated p53 gene transfer. Oncogene. 1998;16:933–943. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi R, Fernandez SC, Murai H, Trusko SP, Scott RW, Nishioka WK, McIntosh TK. BCL-2 overexpression attenuates cortical cell loss after traumatic brain injury in transgenic mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1259–1269. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Raghupathi R, Merry DE, Scherbel U, Saatman KE, McIntosh TK. Overexpression of Bcl-2 is neuroprotective after experimental brain injury in transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:681–692. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991004)412:4<681::aid-cne9>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiambao AB, Tan E, Chang S, Komori N, Naash MI, Peachey NS, Matsumoto H, Ucker DS, Al-Ubaidi MR. Transgenic Bcl-2 expressed in photoreceptor cells confers both death-sparing and death-inducing effects. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73:711–721. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenni MC, Bonfanti L, Martinou JC, Ratto GM, Strettoi E, Maffei L. Long-term survival of retinal ganglion cells following optic nerve section in adult bcl-2 transgenic mice. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8:1735–1745. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane DJ, Sarafian TA, Anton R, Hahn H, Gralla EB, Valentine JS, Ord T, Bredesen DE. Bcl-2 inhibition of neural death: decreased generation of reactive oxygen species. Science. 1993;262:1274–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.8235659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell. 1993;75:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distelhorst CW, Lam M, McCormick TS. Bcl-2 inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced ER Ca2+ pool depletion. Oncogene. 1996;12:2051–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce-Keller AJ, Begley JG, Fu W, Butterfield DA, Bredesen DE, Hutchins JB, Hensley K, Mattson MP. Bcl-2 protects isolated plasma and mitochondrial membranes against lipid peroxidation induced by hydrogen peroxide and amyloid beta-peptide. J Neurochem. 1998;70:31–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70010031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin LA, Schlamp CL, Spieldoch RL, Geszvain KM, Nickells RW. Identification of the bcl-2 family of genes in the rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2545–2553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ST, Garey LJ, Jen LS. Bcl-2 proto-oncogene protein immunoreactivity in normally developing and axotomised rat retinas. Neurosci Lett. 1994;172:11–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ST, Gentleman SM, Garey LJ, Jen LS. Distribution of beta-amyloid precursor and B-cell lymphoma protooncogene proteins in the rat retina after optic nerve transection or vascular lesion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:1073–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ST, Wang JP, Garey LJ, Jen LS. Expression of beta-amyloid precursor and Bcl-2 proto-oncogene proteins in rat retinas after intravitreal injection of aminoadipic acid. Neurochem Int. 1999;35:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang JI, Chen ST, Chang YH, Jen LS. Alteration of Bcl-2 expression in the nigrostriatal system after kainate injection with or without melatonin co-treatment. J Chem Neuroanat. 2001;21:215–223. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(01)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosche J, Hartig W, Reichenbach A. Expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), glutamine synthetase (GS), and Bcl-2 protooncogene protein by Muller (glial) cells in retinal light damage of rats. Neurosci Lett. 1995;185:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)11239-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voehringer DW, Meyn RE. Redox aspects of Bcl-2 function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:537–550. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveraux QL, Schendel SL, Reed JC. Antiapoptotic proteins. The bcl-2 and inhibitor of apoptosis protein families. Cardiol Clin. 2001;19:57–74. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8651(05)70195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwana T, Newmeyer DD. Bcl-2-family proteins and the role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinou JC, Dubois-Dauphin M, Staple JK, Rodriguez I, Frankowski H, Missotten M, Albertini P, Talabot D, Catsicas S, Pietra C, Huarte J. Overexpression of BCL-2 in transgenic mice protects neurons from naturally occurring cell death and experimental ischemia. Neuron. 1994;13:1017–1030. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badrichani AZ, Stroka DM, Bilbao G, Curiel DT, Bach FH, Ferran C. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL serve an anti-inflammatory function in endothelial cells through inhibition of NF-kappaB. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:543–553. doi: 10.1172/JCI2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Park SM, Holleran AL, Murphy AN, Fiskum G, Kane DJ, Testa MP, Kayalar C, Bredesen DE. Shift of the cellular oxidation-reduction potential in neural cells expressing Bcl-2. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1259–1267. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67031259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Hyun DH, Marshall KA, Ellerby LM, Bredesen DE, Jenner P, Halliwell B. Effect of overexpression of BCL-2 on cellular oxidative damage, nitric oxide production, antioxidant defenses, and the proteasome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1550–1559. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoetelmans RW, Vahrmeijer AL, van Vlierberghe RL, Keijzer R, van de Velde CJ, Mulder GJ, Van Dierendonck JH. The role of various Bcl-2 domains in the anti-proliferative effect and modulation of cellular glutathione levels: a prominent role for the BH4 domain. Cell Prolif. 2003;36:35–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2003.00252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaattela M, Benedict M, Tewari M, Shayman JA, Dixit VM. Bcl-x and Bcl-2 inhibit TNF and Fas-induced apoptosis and activation of phospholipase A2 in breast carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1995;10:2297–2305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida N, Sugiyama A, Myoubudani H, Inoue K, Sugamata M, Ihara T, Ueno Y, Tashiro F. Suppression of arachidonic acid cascade-mediated apoptosis in aflatoxin B1-induced rat hepatoma cells by glucocorticoids. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1191–1202. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.7.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery D, Nuñez G, Milliman C, Schreiber RD, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:334–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC, Talwar HS, Cuddy M, Baffy G, Williamson J, Rapp UR, Fisher GJ. Mitochondrial protein p26 BCL2 reduces growth factor requirements of NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1991;195:277–283. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulakia CA, Chen G, Ng FW, Teodoro JG, Branton PE, Nicholson DW, Poirier GG, Shore GC. Bcl-2 and adenovirus E1B 19 kDA protein prevent E1A-induced processing of CPP32 and cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Oncogene. 1996;12:529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardinger C, Brown LF, Roy S, Mizutani M, Zucker CL, Lorenzi M. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in the human retina and in nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1453–1462. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-El-Asrar AM, Dralands L, Missotten L, Al-Jadaan IA, Geboes K. Expression of apoptosis markers in the retinas of human subjects with diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2760–2766. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novack DV, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 protein expression during murine development. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:61–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merry DE, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 gene family in the nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:245–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ST, Hsu JR, Hsu PC, Chuang JI. The retina as a novel in vivo model for studying the role of molecules of the Bcl-2 family in relation to MPTP neurotoxicity. Neurochem Res. 2003;28:805–814. doi: 10.1023/a:1023298604347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardino I, Edelstein D, Brownlee M. Bcl-2 expression or antioxidants prevent hyperglycemia-induced formation of intracellular advanced glycation endproducts in bovine endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1422–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI118563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedziora-Kornatowska KZ, Luciak M, Blaszczyk J, Pawlak W. Effect of aminoguanidine on the generation of superoxide anion and nitric oxide by peripheral blood granulocytes of rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;278:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima K, Sato N, Sato K, Shimizu H, Mori M. Effect of epalrestat, an aldose reductase inhibitor, on the generation of oxygen-derived free radicals in neutrophils from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3404–3408. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.8.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurko R, Siqueira CC, Caldon N, Gao L, Kantarci A, Van Dyke TE. Chronic hyperglycemia predisposes to exaggerated inflammatory response and leukocyte dysfunction in Akita mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:7250–7256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Kantarci A, Hasturk H, Trackman PC, Malabanan A, Van Dyke TE. Activation of RAGE induces elevated O2- generation by mononuclear phagocytes in diabetes. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:520–527. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0406262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubitosi-Klug RA, Talahalli R, Du Y, Nadler JL, Kern TS. 5-Lipoxygenase, but not 12/15-Lipoxygenase. Contributes to degeneration of retinal capillaries in a mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2008;57:1387–1393. doi: 10.2337/db07-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshitari T, Roy S. Diabetes: a potential enhancer of retinal injury in rat retinas. Neurosci Lett. 2005;390:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowluru RA, Abbas SN. Diabetes-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:5327–5334. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podesta F, Romeo G, Liu WH, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Gerhardinger C, Lorenzi M. Bax is increased in the retina of diabetic subjects and is associated with pericyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1025–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64970-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kern TS, Reiter CE, Soans RS, Krady JK, Levison SW, Gardner TW, Bronson SK. The Ins2Akita Mouse as a Model of Early Retinal Complications in Diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2210–2218. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]