Abstract

Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, is increasingly recognized as a novel biomarker in cardiovascular disease. To date, it remains unclear whether elevated ADMA levels are merely associated with cardiovascular risk or whether this molecule is of functional relevance in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic vascular disease. To clarify this issue, we crossed dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) transgenic mice that overexpress the human isoform 1 of the ADMA degrading enzyme DDAH into ApoE-deficient mice to generate ApoE−/−/hDDAH1+/− mice. In these mice, as well as ApoE−/− wild-type littermates, atherosclerosis within the aorta as well as vascular function of aortic ring preparations was assessed. We report here that overexpression of hDDAH1 reduces plaque formation in ApoE−/− mice by lowering ADMA. The extent of atherosclerosis closely correlated with plasma ADMA levels in male but not female mice fed either a standard rodent chow or an atherogenic diet. Functional analysis of aortic ring preparations revealed improved endothelial function in mice overexpressing hDDAH1. Our findings provide proof-of-principle that ADMA plays a causal role as a culprit molecule in atherosclerosis and support recent evidence indicating a functional relevance of DDAH enzymes in genetic mouse models. Together, these results demonstrate that pharmacological interventions targeting the ADMA/DDAH pathway may represent a novel approach in the prevention and management of cardiovascular diseases.

Asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), is considered a novel biomarker in cardiovascular disease.1 Elevated plasma levels of ADMA have been associated with all established cardiovascular risk factors.1 Whether ADMA is simply a marker or a “maker” of vascular disease is still a matter of debate. Recent data from genetic mouse models suggest a functional and causal role for ADMA in the pathophysiology of some models of vascular disease.2,3,4 In these animal models the key regulator of ADMA metabolism, the enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) of which two isoforms with distinct tissue expression have been identified,5 is either knocked-down2 or overexpressed3,4 leading to opposing phenotypes. DDAH catalyzes the hydrolysis of ADMA into L-citrulline and dimethylamine and enzymatic degradation represents the major metabolic pathway of ADMA elimination.

Interestingly, the homozygous knock-down of DDAH1 leads to an embryonic lethal phenotype suggesting a crucial role for this enzyme during embryonic development.2 We have recently generated and characterized transgenic (TG) mice that overexpress the human isoform 1 of DDAH under control of a β-actin promoter in C57Bl/6J mice.3 These animals have lower ADMA levels and an enhanced tissue NOS and DDAH enzyme activity.3 Furthermore, TG mice display an enhanced angiogenic capacity in response to hindlimb ischemia,6 are protected against transplant vasculopathy7 and endothelial injury,8 and are resistant to ADMA-induced endothelial dysfunction.9

The present study was designed to analyze the specific role of ADMA and its degrading enzyme DDAH on plaque formation in a mouse model of atherosclerosis by generating and characterizing ApoE-deficient, human DDAH1 TG mice (ApoE−/−/hDDAH1+/−). Our findings delineate a functional role for ADMA as a culprit molecule in atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Human DDAH1 TG mice (kindly provided by John Cooke, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Stanford University) were generated, maintained, and genotyped as previously described in detail.3,6,7 For the generation of ApoE−/−/hDDAH1+/− mice, female ApoE−/− mice (Apoetm1Unc, stock number: 002052; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) were mated with hDDAH1+/− male mice. Approximately 50% of the F3 generation offsprings were ApoE−/−/hDDAH1+/−; the remaining ApoE−/− littermates served as controls.

Genotyping was performed according to the PCR protocol provided by the vendor (Jackson Laboratories). All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled animal facility with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to tap water and rodent chow. Mice were sacrificed in the morning hours during 08:00 to noon. The study protocol was approved by the animal research ethics committee of the local government (Bezirksregierung Mittelfranken, AZ 54-2531.31-1/06).

Experimental Groups

Structural Studies

Structural analysis of atherosclerosis was analyzed in the following three groups of animals (N = 185):

Group 1 (control group, n = 55): ApoE+/+ male and female mice with (TG) or without (wild-type) overexpression of hDDAH1. These animals received standard rodent chow (Diet 1324, Altromin, Germany) and were sacrificed at the age of 12 months (male: each n = 15; female: wild-type n = 13, TG n = 12).

Group 2 (ApoE−/− on standard diet, n = 57): These ApoE−/− male and female mice with (TG) or without (wild-type) overexpression of hDDAH1 were kept on standard rodent chow (Diet 1324) and sacrificed at the age of 12 months (male: each n = 15; female: wild-type n = 15, TG n = 12). The time-point of sacrifice was chosen based on pilot studies and published data on the natural time course of lesion development and progression in this mouse model under standard rodent chow.10

Group 3 (ApoE−/− on atherogenic diet, n = 73): These ApoE−/− male and female mice with (TG) or without (wild-type) overexpression of hDDAH1 received an atherogenic diet (Diet C1061, Altromin, Germany). This diet contains 7% fat, 1% cholesterol, and 1% sodium cholate. The diet was started at 8 weeks of age over 5 months (male: wild-type n = 24, TG n = 15; female: wild-type n = 22, TG n = 12).

Blood Pressure Measurements

Before sacrifice, blood pressure was measured via carotid artery catheters in conscious mice. Briefly, the right carotid artery was exposed and cannulated with a polyethylene tubing catheter under inhalation anesthesia (isoflurane 2%). The catheter was secured with sutures and subcutaneously tunneled to exit at the back of the neck. The end of the catheter was connected to a Statham pressure transducer and a Gould polygraph. After recovery from the surgical procedure, blood pressure was measured in conscious, restrained animals over 20 minutes. Due to the severity of atherosclerosis, catheter placement or acquisition of reliable pressure amplitudes failed in eight mice of group 2 and was unfeasible in group 3. In the initial phenotypic characterization, overexpression of DDAH1 was associated with a significantly lower blood pressure (∼7 mmHg systolic using tail cuff plethysmography) in conscious mice.3

In the present study (n > 100) we failed to confirm a statistically significant effect of hDDAH1 overexpression on blood pressure by using invasive blood pressure monitoring (as described above). To further clarify this issue, telemetry transmitters (TA-10ETA-F20, Data Sciences, St. Paul, MN) were implanted in male ApoE-competent as well as ApoE-deficient mice (each n = 5) aged 8 weeks. After 1 week of recovery from surgical procedure, blood pressure and heart rate were constantly monitored over 2 weeks.

Laboratory Tests

After blood pressure recordings, animals were exsanguinated under inhalation anesthesia (2% isoflurane) via the carotid artery catheters or via right ventricular cardiac puncture in those animals in which catheterization failed. Whole blood count, urea, total cholesterol, and triglycerides were measured.

Metabolic Cages

Two weeks before sacrifice all animals were housed in metabolic cages over 24 hours for urine collection. Proteinuria was expressed as urinary albumine excretion per Gram creatinine. Albumine was measured by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX); urinary creatinine was determined in the clinical laboratory of the Pediatric Department at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg.

En Face Preparations of the Aorta

Atherosclerosis within the aorta was analyzed in all surviving animals (n = 165) by performing Sudan IV stained en face preparations spanning the entire aorta from the aortic root to the iliac bifurcation. Briefly, on sacrifice mice were perfused with cold saline solution at physiological pressure; thereafter adventitial fatty tissue surrounding the aorta was meticulously dissected under a stereomicroscope by using microscissors. The distal part of the brachiocephalic trunk before the branching of the right subclavian artery was resected and snap frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT (Sakura Finetek Inc., Torrance, CA), whereas the aortic root with the aortic valve was embedded in paraffin for histomorphology.

After fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, the aorta was longitudinally opened and flat-mounted on a dissecting pan covered with wax by using insect pins. Native as well as Sudan IV stained preparations were captured with a digital camera attached to the microscope. Atherosclerotic lesions were quantified by using image analysis software (MetaVue version 4.6r9; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and the lesion area was expressed as a percentage of total aortic surface area. In subanalyses, plaque burden was separately analyzed within the aortic arch and the descending aorta.

Histomorphometry and Immunohistochemistry of the Brachiocephalic Trunk

Cross-sectional lesion formation was analyzed within the distal portion of the brachiocephalic trunk. Cryostat cross sections (8 μm) were stained with H&E or PAS, von Kossa (calcification), Sudan IV (lipid deposition), as well as CD68 (macrophage infiltration). Controls included the omission of primary antibodies.

In situ production of reactive oxygen species within the brachiocephalic trunk was assessed by oxidative fluorescence microscopy by using the fluorescent dye dihydroethidium (DHE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as previously described in detail.11 In some studies, slides were preincubated with 200 U/ml polyethylene glycol-SOD (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Schnelldorf, Germany) to verify specificity of the fluorescent dye.

Measurement of L-Arginine and Methylarginines

Plasma levels of L-arginine, ADMA, as well as symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA), the structural isomer of ADMA that neither inhibits NOS nor is degraded by DDAH, were measured by use of liquid chromatographic-tandem mass spectrometry as previously described.11 Samples were measured in duplicate, and mean values were computed; the intra-assay coefficient of variation was <8%.

DDAH Activity Assay

Because the entire aorta was harvested for en face preparations, DDAH enzyme activity was measured within the skeletal muscle (adductor muscles of the thigh) by use of a recently developed stable-isotope-based assay using deuterium-labeled ADMA ([2H6]-ADMA) as substrate and double stable-isotope labeled ADMA ([13C5-2H6]-ADMA) as internal standard.12 The assay allows simultaneous determination of the formation and metabolism of ADMA in tissue samples by liquid chromatographic-tandem mass spectrometry. Enzyme kinetics as well as tissue levels of ADMA and SDMA were measured in male and female animals of group 2 (each n = 8, total n = 32).

Real-Time RT-PCR Detection of mRNA

Because the entire aorta was harvested for en face preparations, additional male mice (ApoE+/+: wild-type n = 4, TG n = 6; ApoE−/−: wild-type n = 10, TG n = 8) were sacrificed at 12 weeks of age to study mRNA and protein expression of DDAH enzymes. Briefly, RNA was extracted by using RNeasy fibrous tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with TaqMan RT reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by using random hexamers. PCR was performed with an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detector and SYBR green reagents (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were run in triplicate. The relative amount of the specific mRNA of interest was normalized to 18S rRNA. Primer sequences for human and murine DDAH isoforms were as follows: human DDAH1 forward 5′-TCACAGGCAGAGAATTTTTTGTG-3′, human DDAH1 reverse 5′-ACTGTGGAGACTGCATAGTCCTTAAA-3′; mouse DDAH1 forward 5′-GGCGCGCGCTGCTCT-3′, mouse DDAH1 reverse 5′-ACGGTGGCTGGGTTTGAG-3′ (probe 5′FAM-CGGGAGGACCGAGCCACCGA-TAMRA 3′); mouse DDAH2 forward 5′-GGTTGATGGAGTGCGTAAAGC-3′, mouse DDAH2 reverse 5′-TCCACAATTCGGAGTCCCAA-3′.

Western Blotting

Expression of DDAH enzymes within the aorta was determined in ApoE+/+ as well as ApoE−/− mice sacrificed for RNA isolation of aortic tissue (see above). In addition, DDAH1 expression of skeletal muscle, heart, and lung tissue in animals of group 2 (ApoE−/− mice on standard diet) was analyzed. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) and probed with custom made antibodies against DDAH1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:500; Eurogentc, Belgium) or a commercially available DDAH2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). For generation of DDAH1 antibodies, rabbits were immunized by using isoform-specific peptides that cross-react with human and murine DDAH1 (DDAH1 antibodies: EP081322: H2N-RPGAPSRRKEVDMMKC-CONH2, EP081323: H2N-QMSDHRYDKLTVPDDC-CONH2). Sera were affinity purified on an AF-Amino toyopearl 650M matrix by using the respective peptides and 100 mmol/L Glycine (pH 2.5) for elution.

Functional Studies

Vascular function was assessed by using aortic ring preparations of male ApoE+/+ and ApoE−/− mice with or without overexpression of hDDAH1 (each n = 7, total n = 28). Briefly, animals were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation 12 weeks after initiation of an atherosclerotic diet. The distal thoracic aorta was dissected and freed of loose connective tissue. Aortic rings (2 mm) were isolated and mounted on a wire myograph (Danish Myo, Atlanta, GA) for vascular reactivity studies. Contraction and relaxation of isolated vascular preparations were measured in an organ bath containing modified Krebs-Henseleit solution aerated with 95% CO2 − 5%O2, 37°C. Contraction was measured via a force transducer interfaced with AD Instruments (Colorado Springs, CO) software for data analysis. After a 60-minute equilibration period, the rings were stretched to generate a resting tension of 0.5 g. The optimum resting force of the aortic rings was determined by comparing the force developed by 40 mmol/L KCl under different resting force. After preconstriction of the vascular rings with 0.5 μmol/L phenylephrine, the relaxation response was determined by using increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (10 nmol/L to 5 μmol/L).

After three sequential Ach dose responses, the vascular relaxation response to the NO donor 1,1-diethyl-2-hydroxy-2-nitrozohydrazine (DEANOate; 10 nmol/L to 500 nmol/L) was performed to assess smooth muscle responses to NO. All reagents were prepared in aqueous solvent or Krebs Buffer containing indomethacin (10 μmol/L).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS software package (version 16.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Differences between wild-type and TG mice in each subgroup were first analyzed by using the unpaired t-test. Within each gender, differences between the three study groups were further analyzed by using one-way analysis of variance with posthoc Bonferroni correction (six groups). In addition, a univariate linear model was used to analyze DDAH1 genotype dependent effects throughout the three treatment groups. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated when indicated. All data are given as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was accepted at a value of P < 0.05 (two-sided).

Results

Animals

All control mice of group 1 (ApoE+/+, n = 55) survived until sacrifice; in group 2 (ApoE−/− on standard diet, n = 57) one female hDDAH1 TG mouse died after 5 months. In group 3 (ApoE−/− on atherogenic diet, n = 73) 19 animals (∼26%) did not survive until sacrifice. Mortality tended to be higher in wild-type compared with TG mice (male wild-type: 8 of 24, male TG: 3 of 15; female wild-type: 6 of 22, female TG: 2 of 12; log rank test for cumulative survival, P = NS). Mean duration until death was 55 ± 10 days. The atherogenic diet led to substantial weight loss, which was more pronounced in animals that died versus those that survived (6.5 ± 0.7 vs. 3.0 ± 0.3 g, P < 0.0001) and more aggravated in male versus female mice (4.0 ± 0.5 vs. 1.9 ± 0.3 g, P = 0.001).

Blood Pressure and Laboratory Parameters

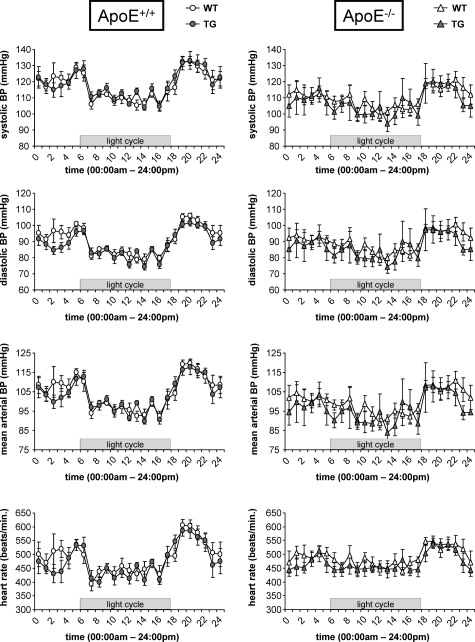

Clinical characteristics and laboratory parameters for male and female mice are shown in Table 1. Blood pressure was similar between wild-type and hDDAH1 TG as well as ApoE+/+ and ApoE−/− mice (Table 1). The lack of an effect of DDAH overexpression on hemodynamics was confirmed by using telemetry transmitters. Blood pressure tended to be somewhat lower in ApoE−/− versus ApoE+/+ mice (P = NS); however, mean arterial pressure and heart rate were similar in wild-type versus TG mice (ApoE+/+ wild-type versus TG, mean arterial pressure: 104.1 ± 1.4 vs. 103.5 ± 1.2 mmHg, heart rate: 487 ± 15 vs. 480 ± 11 beats/minute, P = NS; ApoE−/− wild-type versus TG, mean arterial pressure: 99.7 ± 1.5 vs. 97.0 ± 4.7 mmHg, heart rate: 486 ± 12 vs. 477 ± 9 beats/minute, P = NS; Figure 1). Both blood pressure as well as heart rate variability were reduced in ApoE−/− versus ApoE+/+ mice (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and Laboratory Chemistry in Male and Female Mice

| Variable | Group 1

|

Group 2

|

Group 3

|

Analysis of variance between groups P | DDAH1 genotype effect P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoE+/+ (standard diet)

|

ApoE−/− (standard diet)

|

ApoE−/− (atherogenic diet)

|

|||||||||

| WT (♂ = 15/♀ = 13) | TG (♂ = 15/♀ = 12) | P | WT (♂ = 15/♀ = 15) | TG (♂ = 15/♀ = 11) | P | WT (♂ = 16/♀ = 16) | TG (♂ = 12/♀ = 10) | P | |||

| Weight, g | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 32.0 ± 0.4 | 33.2 ± 0.6 | NS | 30.9 ± 0.5 | 31.6 ± 0.7 | NS | 19.7 ± 0.4 | 18.9 ± 0.5 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Female mice | 23.8 ± 0.4‡ | 24.6 ± 0.5‡ | NS | 25.8 ± 0.4‡ | 25.5 ± 0.4‡ | NS | 18.1 ± 0.5* | 17.2 ± 0.5* | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| MAP, mmHg | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 103 ± 2 | 100 ± 1 | NS | 103 ± 1 | 103 ± 2 | NS | NP | NP | — | NS | NS |

| Female mice | 104 ± 2 | 102 ± 2 | NS | 104 ± 2 | 102 ± 2 | NS | NP | NP | — | NS | NS |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 14.2 ± 0.3 | 14.2 ± 0.2 | NS | 11.9 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 0.5 | NS | ND | ND | — | <0.01 | NS |

| Female mice | 15.1 ± 0.2* | 14.8 ± 0.3 | NS | 13.7 ± 0.5* | 14.9 ± 0.6* | NS | ND | ND | — | <0.05 | NS |

| Urea, mg/dl | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 51.0 ± 2.1 | 53.4 ± 2.8 | NS | 64.3 ± 4.2 | 63.3 ± 2.7 | NS | 60.1 ± 3.3 | 63.4 ± 4.6 | NS | <0.05 | NS |

| Female mice | 46.4 ± 2.6 | 53.5 ± 2.5 | NS | 66.8 ± 2.9 | 67.6 ± 4.7 | NS | 62.2 ± 3.6 | 65.3 ± 4.4 | NS | <0.001 | NS |

| UAE, mg/g creatinine | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 171 ± 20 | 163 ± 11 | NS | 245 ± 35 | 204 ± 29 | NS | 475 ± 191 | 257 ± 72 | NS | NS | NS |

| Female mice | 193 ± 11 | 187 ± 13 | NS | 131 ± 13† | 162 ± 20 | NS | 552 ± 138 | 449 ± 124 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 71 ± 4 | 75 ± 3 | NS | 399 ± 23 | 377 ± 21 | NS | 1546 ± 79 | 1763 ± 74 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Female mice | 60 ± 2* | 58 ± 2‡ | NS | 341 ± 14* | 340 ± 15 | NS | 1629 ± 141 | 1827 ± 213 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 82 ± 9 | 77 ± 10 | NS | 117 ± 16 | 107 ± 11 | NS | 204 ± 22 | 161 ± 15 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Female mice | 56 ± 3* | 60 ± 5 | NS | 88 ± 8 | 83 ± 6 | NS | 193 ± 20 | 194 ± 24 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| ADMA, μM | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Female mice | 0.61 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.02‡ | <0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.04* | 0.54 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.60 ± 0.03† | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| SDMA, μM | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | NS | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | NS | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| Female mice | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | NS | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | NS | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| L-arginine, μM | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 76.7 ± 5.3 | 80.3 ± 4.0 | NS | 73.6 ± 6.9 | 71.5 ± 6.7 | NS | 72.1 ± 3.9 | 73.2 ± 3.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Female mice | 94.3 ± 7.1 | 94.2 ± 6.6 | NS | 92.4 ± 6.2 | 93.5 ± 8.9 | NS | 77.9 ± 3.3 | 81.7 ± 7.5 | NS | NS | NS |

| L-arginine/ADMA | |||||||||||

| Male mice | 144 ± 11 | 231 ± 12 | <0.0001 | 110 ± 10 | 171 ± 18 | <0.01 | 82 ± 4 | 167 ± 9 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Female mice | 160 ± 13 | 204 ± 16 | <0.05 | 117 ± 9 | 177 ± 12 | <0.01 | 81 ± 4 | 140 ± 11 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

ND, not done; NP, not possible; MAP, mean arterial pressure; UAE, urinary albumine excretion, neither MAP nor hemoglobin was measured in this group of animals; accordingly, no statistics could be performed.

P < 0.05 versus male mice.

P < 0.01 versus male mice.

P < 0.001 versus male mice.

Figure 1.

Blood pressure telemetry in ApoE+/+ (left columns) and ApoE−/− (right columns) mice with or without overexpression of hDDAH1 (each n = 5). Recordings were obtained in 8-week-old male mice kept on standard rodent chow. Each line represents mean values obtained over 24 hours over a period of 2 weeks. (BP = blood pressure).

Total cholesterol levels were approximately fivefold elevated in ApoE−/− mice on standard rodent diet and ∼20-fold elevated in ApoE−/− mice on atherogenic diet compared with the control group (P < 0.0001; Table 1). In contrast, triglycerides were only mildly elevated (1.5-fold and 3.0-fold, respectively).

Plasma ADMA levels were significantly lower in TG versus wild-type mice of all treatment groups (Table 1). Mean ADMA levels in all wild-type versus all TG mice were 0.76 ± 0.02 vs. 0.46 ± 0.01 μmol/L (P < 0.00001). Overall, plasma ADMA levels were significantly higher in female versus male mice (0.69 ± 0.03 vs. 0.57 ± 0.02 μmol/L, P = 0.0003). In addition, the effect of the transgene on plasma ADMA levels was somewhat lower in female (∼35% lower ADMA levels versus wild-type) opposed to male mice (∼40% lower ADMA levels versus wild-type) throughout all treatment groups (Table 1). As expected, ADMA levels were significantly elevated in ApoE−/− mice compared with ApoE+/+ control mice (Table 1). SDMA levels did not differ between gender and genotype but significantly increased throughout the treatment groups (Table 1). L-arginine levels were similar between genotypes and treatment groups. The L-arginine/ADMA ratio was significantly higher in TG mice and declined throughout the treatment groups (Table 1).

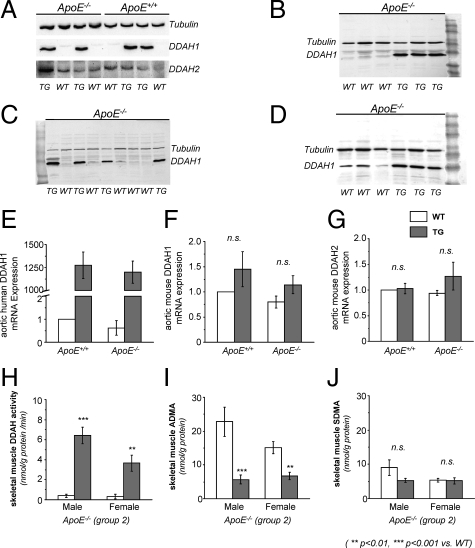

DDAH Expression and Activity

Through the use of a polyclonal antibody against DDAH1 (reacts with mouse and human), ample expression of DDAH1 within the aorta was observed in TG mice (Figure 2A). Protein expression did not differ between ApoE+/+ and ApoE−/− mice (Figure 2A). DDAH1 was also abundantly expressed in skeletal muscle, heart, and lung tissue of TG mice (Figure 2, B–D). In wild-type mice the greatest expression of DDAH1 was seen in lung tissue (Figure 2D). Within the aortae we could not detect DDAH1 protein expression in wild-type mice. In contrast, DDAH2 was expressed in aortae of all mice (Figure 2A). The protein expression pattern was confirmed on the transcriptional level by using RT-PCR. By use of a transgene-specific primer for the human isoform of DDAH1, marked expression was seen in TG mice (Figure 2E). Expression of endogenous murine DDAH isoforms (mDDAH1 and mDDAH2) did not differ between wild-type and TG or ApoE+/+ versus ApoE−/− mice (Figure 2, F and G).

Figure 2.

DDAH1 expression and activity (WT = wild-type; TG = hDDAH1+/− transgenic). DDAH protein expression: aorta (A), skeletal muscle (B), heart (C), and lung (D). mRNA expression: mRNA expression of hDDAH1 within the aorta (E), murine DDAH1 mRNA expression within the aorta (F), and murine DDAH2 mRNA expression within the aorta (G). Data expressed as fold increase versus wild-type ApoE+/+ (control). DDAH activity: skeletal muscle DDAH activity (H), tissue ADMA levels within the skeletal muscle (I), and tissue SDMA levels within the skeletal muscle (J).

Skeletal muscle DDAH activity was markedly enhanced in ApoE−/− mice overexpressing hDDAH1 (Figure 2H). Enzyme activity was greater in male versus female TG mice (6.42 ± 0.81 vs. 3.65 ± 0.82 nmol/g protein/minute, P < 0.05). Skeletal muscle tissue ADMA levels were significantly lower in TG versus wild-type mice, whereas SDMA levels were similar (Figure 2, I and J).

Assessment of Atherosclerotic Lesions within the Aorta

Group 1

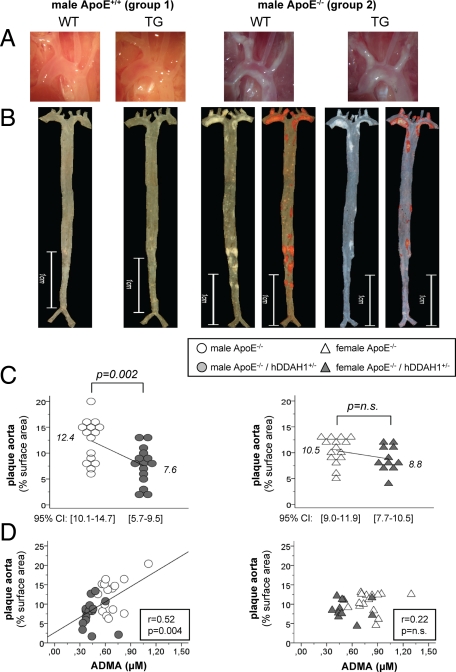

Regardless of genotype, none of the ApoE+/+ mice (n = 55) developed any atherosclerotic lesions within the aorta after 1 year (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3.

Atherosclerosis in mice of groups 1 and 2. A: native aspect of the aortic arch. B: native as well as Sudan IV stained en face preparation of the aorta. C: atherosclerosis in male (circles) and female (triangles) ApoE−/− mice kept on standard diet (group 2). D: correlation between ADMA levels and atherosclerosis in male (circles) and female (triangles) ApoE−/− mice kept on standard diet (group 2). CI = confidence interval.

Group 2

In ApoE−/− mice kept on standard diet, overexpression of hDDAH1 significantly attenuated plaque formation in male (∼39%) but not female (∼16%) mice (Figure 3, B and C). Notably, aortic surface area did not differ between genotypes (58.3 ± 1.7 vs. 58.2 ± 1.3 mm2). Under standard diet, plaque formation was most prominent within the ascending aorta and the aortic arch with its three major branches (Figure 3, A and B). In this anatomical region plaque burden only tended to be lower in male TG versus wild-type mice (43.5% vs. 32.8% of surface area, P = NS). In contrast, overall plaque burden in the descending aorta was low, and plaques were mostly located below the diaphragm, whereas the thoracic aorta was largely devoid of any lesions. Atherosclerosis in the descending aorta was markedly reduced in male TG versus wild-type mice (5.5% vs. 2.7%, P = 0.008).

ADMA levels significantly correlated with the degree of plaque burden within the aorta of male mice (Figure 3D). Furthermore, an inverse correlation between the L-arginine/ADMA ratio and plaque burden was observed in male mice (r = −0.47, P = 0.008). Plasma SDMA levels did not correlate with the degree of atherosclerosis in male mice (r = 0.32, P = NS). However, a strong correlation between albuminuria and atherosclerosis was noted in male mice (r = 0.58, P = 0.001). None of the lipid profile parameters were related to the extent of atherosclerosis.

In ApoE−/− female mice maintained on a standard diet, atherosclerosis in the aorta did not differ between wild-type and TG animals, although a trend toward a lower plaque burden in TG animals was evident (∼16%, Figure 3C). In contrast to male mice, the distribution of plaques in the aorta of female mice was less scattered, and plaque burden in the descending aorta was somewhat lower in wild-type mice. In female mice ADMA levels did not correlate with the degree of atherosclerosis in the aorta (Figure 3D). In addition, L-arginine/ADMA ratio, proteinuria, as well as lipid parameters did not correlate with the degree of atherosclerosis (data not shown).

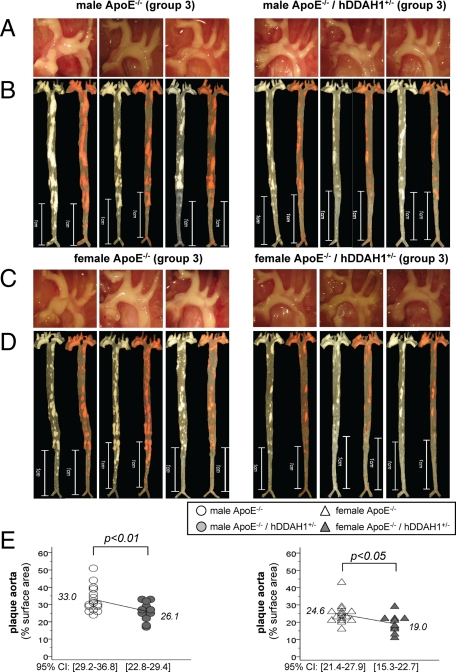

Group 3

In ApoE−/− mice kept on an atherogenic diet for 5 months, overexpression of hDDAH1 reduced atherosclerotic lesion formation in both male (∼21%) and female (∼23%) mice (Figure 4, A–E). Overall, atherosclerosis within the entire aorta was more pronounced in male versus female mice (30.0 ± 1.4% vs. 22.5 ± 1.2%, P = 0.0001). Plaque burden in the aortic arch was massive and only tended to be lower in TG versus wild-type mice (male mice: ∼15%, female mice: ∼11%, P = NS, data not shown). Major differences between the two genotypes were due to reduced plaque burden in the descending aorta (male mice: ∼25%, female mice: ∼34%, P < 0.05; Figure 4, B and D). Again, plaque content in the aorta significantly correlated with ADMA levels in male (r = 0.46, P = 0.015) but not female mice (r = 0.31, P = NS). Likewise, an inverse correlation between the L-arginine/ADMA ratio and atherosclerosis was noted in male (r = −0.45, P = 0.016) but not female mice (r = −0.35, P = NS). Proteinuria showed greater variation and did not correlate with atherosclerosis in either sex.

Figure 4.

Atherosclerosis in male and female ApoE−/− mice on atherogenic diet (group 3). A: native aspect of the aortic arch in male mice (n = 3). B: native as well as Sudan IV stained en face preparation of the aorta in male mice (n = 3). C: native aspect of the aortic arch in female mice (n = 3). D: native as well as Sudan IV stained en face preparation of the aorta in female mice (n = 3). E: degree of atherosclerosis in male (circles) and female (triangles) ApoE−/− mice kept on an atherogenic diet (group 3). CI = confidence interval.

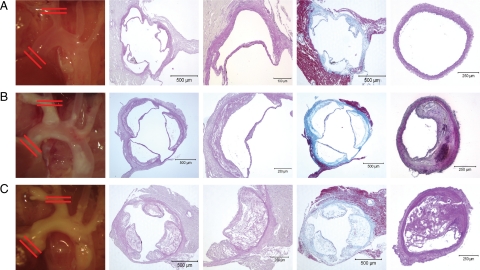

Plaque Histomorphometry of Aortic Root and Brachiocephalic Trunk

Marked atheromata were seen in the aortic root of ApoE−/− mice of groups 2 and 3 (Figure 5, A–C). High power views showed dissolved cholesterol crystals in paraffin embedded cross sections. Trichrome staining revealed marked perivalvular fibrosis in ApoE−/− mice. Overall, the microscopic aspect of aortic root sections did not differ between wild-type and hDDAH1 TG mice.

Figure 5.

Lesion assessment of the aortic root and brachiocephalic trunk. A: Group 1 (ApoE+/+, standard diet). B: Group 2 (ApoE−/−, standard diet). C: Group 3 (ApoE−/−, atherogenic diet). In each panel the following images are shown from left to right. Image 1: native aspect of aortic arch; red lines indicate cross-sectional area for analysis of aortic root (images 2 to 4) and brachiocephalic trunk (image 5). Image 2: PAS stained cross sections of aortic root. Image 3: high power view of aortic leaflet showing atheromata in animals of groups 2 and 3. Image 4: trichrome staining of aortic root showing perivalvular fibrosis in ApoE−/− mice. Image 5: cross section of the brachiocephalic trunk showing plaques in ApoE−/− mice.

Regardless of DDAH1 genotype, none of the control mice (group 1) showed atherosclerotic plaques within the distal brachiocephalic trunk (Figure 5A). In contrast, marked neointima formation was noted in mice of groups 2 and 3 (Figure 5, B and C). Luminal narrowing by atherosclerotic plaques was most advanced in mice on atherogenic diet (Figure 5C). Neointima formation and luminal narrowing within the brachiocephalic trunk was significantly lower in female but not male TG mice opposed to wild-type animals (Supplemental Table 1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). In addition, macrophage infiltration was lower in female but not male TG animals compared with wild-type mice (Supplemental Table 1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). All other histomorphometric parameters did not differ between genotypes.

However, plaque morphology in animals of groups 2 and 3 markedly differed in several aspects. In ApoE−/− mice on standard diet (group 2), vascular calcifications were noted in most animals and were more frequent in female than male mice (Supplemental Table 1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org; Figure 6A). Calcifications were not only seen within the plaques; more strikingly marked media-calcinosis was noted in nine male (n = 6 wild-type and n = 3 TG) and 11 female (n = 9 wild-type and n = 2 TG) mice of group 2 (Figure 6A). In contrast, no calcifications were seen in ApoE−/− mice kept on an atherogenic diet (group 3; Figure 6B). In these animals plaques were soft and lipid rich as evidenced by intense Sudan IV staining. In contrast, Sudan IV staining was restricted to foam cell rich lesions facing the vessel lumen in mice of group 2 (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

Plaque histomorphology of the brachiocephalic trunk. A: ApoE−/− on standard diet. B: ApoE−/− on atherogenic diet. C: CD68 immunofluorescence (asterisks denote calcified vessel wall). D: DDAH1 immunofluorescence. E: DDAH1 and CD68 co-immunofluorescence.

Marked macrophage infiltration (CD68 staining) was seen within atherosclerotic plaques by using light (Figure 6, A and B) or fluorescence microscopy (Figure 6C). Co-staining for α-smooth muscle actin revealed migration of vascular smooth muscle cells into the plaque shoulder in most animals (Figure 6C). DDAH1 immunofluorescence was only detectable in TG mice and was most abundant within the plaques (Figure 6D) where expression co-localized with CD68 immunofluorescence (Figure 6E).

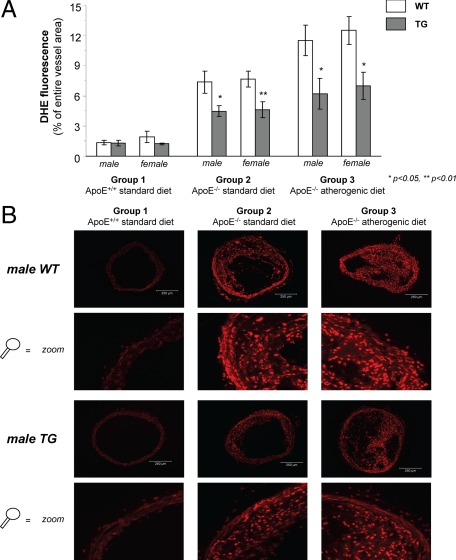

Vascular oxidative stress within the aorta was analyzed by DHE fluorescence and was markedly reduced in TG mice of groups 2 and 3 (Figure 7, A and B). Scarce fluorescence was noted in mice of the control group with no differences between genotypes. Reduced oxidative stress in ApoE−/− TG mice was confirmed by using nitrotyrosine staining (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Vascular oxidative stress using DHE fluorescence. A: DHE fluorescence within the brachiocephalic trunk in animals of groups 1 to 3. B: representative images showing DHE fluorescence in mice of groups 1 to 3.

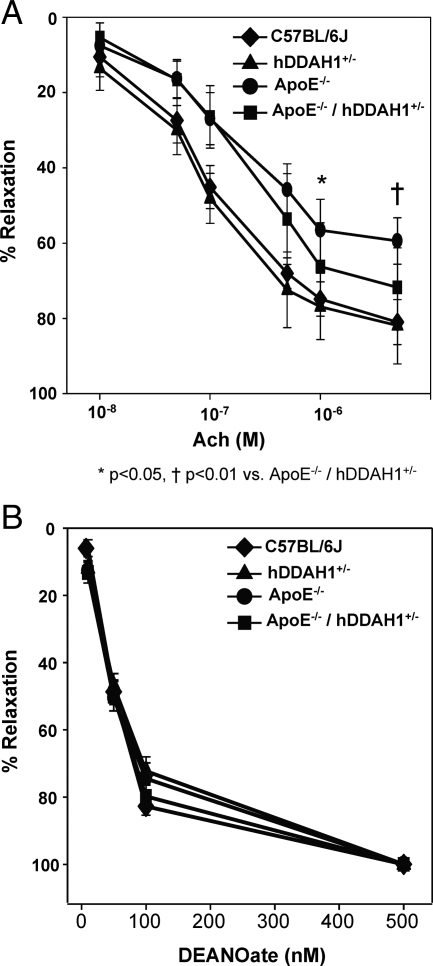

Functional Studies

Twelve weeks after initiation of an atherosclerotic diet, ApoE−/− exhibited a ∼27% decrease in endothelium-dependent vasodilation to acetycholine 5 μmol/L (C57BL/6J versus ApoE−/−: 81.0 ± 2.2% vs. 59.4 ± 2.3%, P < 0.0001). To assess whether the impaired vascular function was attributed to ADMA, we examined the effects of hDDAH1 overexpression on endothelium-dependent vasodilation in ApoE−/− mice. At concentrations of acetylcholine >500 nmol/L, hDDAH1 overexpression was able to significantly increase endothelium-dependent relaxation (Figure 8A). At 5 μmol/L acetylcholine, ApoE−/−/hDDAH1+/− mice exhibited 73% relaxation, whereas ApoE−/− mice exhibited 59% relaxation (P = 0.009; Figure 8A). No significant difference was observed between ApoE+/+ wild-type (81%) versus ApoE+/+ TG (82%) mice, suggesting that basal levels of methylarginines are insufficient to modulate endothelial NO production. Of note, the contractile response to phenylephrine was similar between experimental groups; the average contractile response was 1.7 to 1.9 mN/mm among all groups. Endothelium-independent vasodilation in response to the NO donor DEANOate did not differ between experimental groups (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Vascular function studies in ApoE+/+ and ApoE−/− mice with or without overexpression of hDDAH1. A: Endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to acetylcholine (10 nmol/L to 5 μmol/L). B: Endothelium-independent vasodilation in response to DEANOate (10 nmol/L to 500 nmol/L).

Discussion

The salient findings of the present study are that overexpression of the ADMA degrading enzyme DDAH1 reduces plaque formation and improves vascular function in a mouse model of overt atherosclerosis.

ADMA has long been identified as a putative biomarker in cardiovascular disease; however, until now it remained inconclusive whether elevations in the levels of this molecule are a consequence of vascular disease or whether ADMA plays a causal and thus functional role in atherosclerosis. Our findings provide proof-of-principle that ADMA is a culprit molecule in the onset and progression of atherosclerosis.

NO exerts multiple biological functions and has long been identified as a key antiatherogenic molecule. Not surprisingly, ApoE/eNOS double mutant mice are characterized by enhanced atherosclerosis,13,14 a finding that is independent of elevations in blood pressure.15 ADMA is an endogenous inhibitor of all three NOS isoforms and competes with the physiological substrate, the amino acid L-arginine, for the enzyme. It was thus conceivable that ADMA exacerbates atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice.

Complementary to our findings, a recent study in ApoE−/− mice demonstrated that exogenous ADMA accelerates plaque formation.16 These findings suggest an association between elevated ADMA levels and atherosclerosis but do not establish the causative role of endogenous ADMA. Similar findings have been made by other investigators using the nonselective NOS inhibitor NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME).17 In these studies, the authors also performed functional experiments by using isolated vessel preparations and demonstrated marked inhibition of NO-mediated vascular responses in ApoE−/− mice.

We extend previous observations by providing clear evidence regarding the functional relevance of endogenous ADMA and its degrading enzyme DDAH in atherosclerosis. Overexpression of DDAH, the key regulator of ADMA metabolism, markedly reduced lesion formation in ApoE−/− mice. We observed a close relationship between ADMA levels and plaque burden in male but not female mice. In addition to the detailed structural analysis of atherosclerosis, results of our functional studies demonstrated that in fact a reduction in ADMA bioavailability through hDDAH1 overexpression affords a vascular protective effect manifested through improved endothelium-dependent relaxation.

Given the fact that ADMA inhibits all three NOS enzymes, the molecule may also affect the inducible NOS isoform. Enhanced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity as a consequence of lower ADMA levels in DDAH1 TG mice may be associated with enhanced inflammation. However, this was not the case because iNOS mRNA expression in carotid arteries and iNOS immunostaining within the brachiocephalic trunk did not differ between wild-type and TG mice (data not shown). Furthermore, macrophage infiltration within atherosclerotic lesions was lower in female TG versus wild-type mice and was comparable in male mice.

With respect to diet-induced atherosclerosis, we are fully aware that animals of group 3 (ApoE−/− on atherogenic diet) represent a model of accelerated and severe atherosclerosis. Accordingly, we do believe that findings of group 3 have to be interpreted with caution. In general, atherogenic diets used in rodents are associated with marked alterations in lipid profiles within a rather short time frame, a condition that does not mimic the situation seen in humans. Indeed, plaque morphology markedly differed between ApoE-deficient mice kept on standard rodent chow versus atherogenic diet. Whereas in the former group plaques were calcified, the latter group revealed lipid rich soft lesions that lacked calcifications. Despite the obvious limitations of the atherogenic diet, a clear cut effect of the DDAH transgene on atherosclerosis was seen in both genders.

To circumvent the problem of diet-induced alterations in lipid profiles, we undertook additional studies using aged ApoE−/− mice on standard diet to evaluate the natural course of atherosclerosis and the effect of the hDDAH1 transgene in this mouse model. Lipid profiles observed in ApoE−/− on standard diet are clearly more compatible with the situation seen in hypercholesterolemic humans and were in line with the initial phenotypic characterization of these mice.18

Our results in this group of animals reveal a clear functional role of ADMA in the progression of atherosclerosis in male mice. Overexpression of hDDAH1 markedly reduced atherosclerotic lesion formation. Differences were largely due to lower plaque burden in the descending aorta. It is tempting to speculate that we may have missed significant differences in plaque burden within the aortic arch between wild-type and TG mice simply because the time-point of sacrifice was too late and atherosclerosis was markedly advanced in this anatomical region. Indeed, cross-sectional analysis of lesions within the innominate artery revealed massive atherosclerotic foci with marked luminal narrowing in ApoE−/− mice. The severity as well as morphology of lesions was in close agreement with observations made by other investigators.19

In female mice atherosclerosis within the aorta did not differ between wild-type and TG mice, although a trend toward lower plaque burden in mice overexpressing hDDAH1 was clearly evident. Possible explanations are manifold. First and foremost, gender specific differences in plaque distribution and morphology have been previously described in ApoE−/− mice.20 These have in part been explained by differences in hormone status, in especially estrogens.20,21 In postmenopausal women oral estrogens reduce levels of ADMA and L-arginine.22 Consequently, lack of estrogens in our aged female mice (group 2) may help to explain the observed elevations of both these molecules compared with male mice. Second, characteristics between male and female mice of group 2 differed in several aspects. Thus, female mice were less anemic, less proteinuric, and had a more favorable lipid profile than male mice. Third, in agreement with other investigators,23 we noted a greater variability in plaque distribution particularly in the descending aorta of male versus female mice. Finally, and most importantly, the overall effect of the transgene on plasma ADMA levels was lower in female versus male mice in all groups. All these variables may help to explain the observed gender differences.

In agreement with other investigators,16,24 ApoE-deficiency was associated with higher plasma ADMA levels as evidenced in the direct comparison between mice of groups 1 and 2. Comparable differences of plasma ADMA levels have been described in hyper- versus normocholesterolemic humans.25

Interestingly, cholesterol levels did not correlate with plasma ADMA levels in any of the treatment groups. This finding is in agreement with large clinical trials that revealed no relationship between the two parameters in humans.26,27 Not surprisingly, lipid lowering therapy with statins has failed to lower ADMA levels in most clinical studies.28 Furthermore, cholesterol levels did not correlate with the degree of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. This is also in line with reports in the literature.29,30

A striking observation that we have also noticed in a previous study11 was the fact that overexpression of hDDAH1 is associated with less vascular oxidative stress as evidenced by reduced DHE fluorescence within vascular lesions of the brachiocephalic trunk of ApoE−/− mice. Notably, DDAH is a redox-sensitive enzyme that results from a critical sulfhydryl group within the catalytic site. The cysteine residue is susceptible to both oxidation and regulation by nitric oxide.31 There is evidence that ADMA may facilitate eNOS uncoupling and thereby enhance oxidative stress via generation of superoxide anions.32 Enhanced degradation of ADMA by DDAH may therefore be vasoprotective.

Our studies are limited in that we cannot rule out ADMA-independent effects of DDAH overexpression. Until now, the two methylarginines ADMA and NG-monomethyl-L-arginine are the only identified substrates of DDAH enzymes, whereas SDMA due to its sterical conformation is inert to enzymatic degradation by the enzyme. The homozygous knock-out of DDAH1 in mice is lethal providing strong evidence that DDAH effects are not limited to NG-monomethyl-L-arginine or ADMA dependent regulation of NOS. Recent in vitro studies using gene silencing techniques demonstrate that down-regulation of DDAH1 or DDAH2 using small-interfering RNA reduced NO bioavailability by 27% and 57%, respectively.33 Intriguingly, DDAH1 gene silencing was associated with a 48% reduction in the L-arginine/ADMA ratio that could be restored by L-arginine supplementation, whereas the ratio remained unchanged in DDAH2 silenced cells in which L-arginine had no effect on NO.33 These studies indicate that DDAH1 and DDAH2 manifest their effects through different mechanisms, the former of which is largely ADMA-dependent, whereas the latter is ADMA-independent. The precise role of each enzyme in regulating methylarginine metabolism and NO bioavailability as well as possible other targets need to be further investigated.

Of note, blood pressure was similar in ApoE-competent and ApoE-deficient mice as well as wild-type and TG mice. Thus, reduced atherosclerosis in TG mice was not confounded by systemic hemodynamics. In our initial phenotypic characterization, overexpression of hDDAH1 was associated with a minor, yet significant, reduction of systolic blood pressure in conscious mice using tail-cuff pletysmography (n = 6). In the present study we used more sophisticated methods of blood pressure determination, namely invasive blood pressure monitoring in conscious mice via polyethylene catheters (n >100 mice) or telemetric transmitters (n = 20). With both methods we did not observe any differences in hemodynamics between genotypes.

The lack of a blood pressure difference between ApoE-competent versus ApoE-deficient mice stands in contrast to telemetric recordings obtained in age-matched mice by others. Thus, Pelat et al34 observed a marked increase of both blood pressure (∼24 mmHg systolic and ∼11 mmHg diastolic) and heart rate (∼70 beats/minute) in ApoE-deficient mice. In addition, the authors observed a reduced diurnal variability of both blood pressure and heart rate in these animals.34 We can only confirm the latter observation in our telemetry studies. If any, blood pressure tended to be lower in young ApoE−/− versus ApoE+/+ male mice. Of note, the cardiovascular system phenotype database of ApoE-deficient mice provided by the vendor lacks evidence of alterations in blood pressure or heart rate (Jackson Laboratories). Differences between our findings and those of Pelat et al34 may be related to the genetic background of ApoE-deficient mice or differences in rodent diet. Accordingly, our mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, whereas Pelat et al34 obtained mice from Charles River UK, Ltd., (Margate, UK). The observed differences highlight the need of appropriate control animals and state of the art techniques for measurement of hemodynamics in rodents.

In conclusion, overexpression of the ADMA degrading enzyme DDAH1 lowers atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. Our findings support recent evidence indicating a functional and thus causal role of ADMA in cardiovascular diseases. Lowering ADMA levels via modulation of expression or activity of DDAH may become a promising pharmacological tool in the management of cardiovascular disorders.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Ortrun Alter and Rainer Wachtveitl for expert technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Johannes Jacobi, M.D., Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Krankenhausstr. 12, Erlangen D-91054, Germany. E-mail: johannes.jacobi@uk-erlangen.de.

Supported by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) at the University Hospital of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (project B12) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO 106/2-1).

R.M., E.S. and R.H.B. have a share in patents on asymmetric dimethylarginine assays and receive royalties from the licenses.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Cooke JP. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine: the Uber marker? Circulation. 2004;109:1813–1818. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126823.07732.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper J, Nandi M, Torondel B, Murray-Rust J, Malaki M, O'Hara B, Rossiter S, Anthony S, Madhani M, Selwood D, Smith C, Wojciak-Stothard B, Rudiger A, Stidwill R, McDonald NQ, Vallance P. Disruption of methylarginine metabolism impairs vascular homeostasis. Nat Med. 2007;13:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nm1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayoub H, Achan V, Adimoolam S, Jacobi J, Stuehlinger MC, Wang BY, Tsao PS, Kimoto M, Vallance P, Patterson AJ, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates nitric oxide synthesis: genetic and physiological evidence. Circulation. 2003;108:3042–3047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101924.04515.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa K, Wakino S, Tatematsu S, Yoshioka K, Homma K, Sugano N, Kimoto M, Hayashi K, Itoh H. Role of asymmetric dimethylarginine in vascular injury in transgenic mice overexpressing dimethylarginie dimethylaminohydrolase 2. Circ Res. 2007;101:e2–e10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper JM, Santa Maria J, Chubb A, MacAllister RJ, Charles IG, Whitley GS, Vallance P. Identification of two human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases with distinct tissue distributions and homology with microbial arginine deiminases. Biochem J. 1999;343:209–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi J, Sydow K, von Degenfeld G, Zhang Y, Dayoub H, Wang B, Patterson AJ, Kimoto M, Blau HM, Cooke JP. Overexpression of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase reduces tissue asymmetric dimethylarginine levels and enhances angiogenesis. Circulation. 2005;111:1431–1438. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158487.80483.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Sydow K, Gunawan F, Jacobi J, Tsao PS, Robbins RC, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase overexpression suppresses graft coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2005;112:1549–1556. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.537670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi H, Sydow K, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase promotes endothelial repair after vascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayoub H, Rodionov R, Lynch C, Cooke JP, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Lentz SR, Faraci FM. Overexpression of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase inhibits asymmetric dimethylarginine-induced endothelial dysfunction in the cerebral circulation. Stroke. 2008;39:180–184. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddick RL, Zhang SH, Maeda N. Atherosclerosis in mice lacking apo E: evaluation of lesional development and progression. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:141–147. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi J, Maas R, Cordasic N, Koch K, Schmieder RE, Boger RH, Hilgers KF. Role of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) for angiotensin II-induced target organ damage in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1058–H1066. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01103.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas R, Tan-Andreesen J, Schwedhelm E, Schulze F, Boger RH. A stable-isotope based technique for the determination of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) activity in mouse tissue. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2007;851:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JW, Reddick RL, Jennette JC, Shesely EG, Smithies O, Maeda N. Enhanced atherosclerosis and kidney dysfunction in eNOS(−/−)Apoe(−/−) mice are ameliorated by enalapril treatment. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:451–458. doi: 10.1172/JCI8376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlencordt PJ, Gyurko R, Han F, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Aretz TH, Hajjar R, Picard MH, Huang PL. Accelerated atherosclerosis, aortic aneurysm formation, and ischemic heart disease in apolipoprotein E/endothelial nitric oxide synthase double-knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;104:448–454. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.091399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kuhlencordt PJ, Astern J, Gyurko R, Huang PL. Hypertension does not account for the accelerated atherosclerosis and development of aneurysms in male apolipoprotein e/endothelial nitric oxide synthase double knockout mice. Circulation. 2001;104:2391–2394. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.099729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao HB, Yang ZC, Jia SJ, Li NS, Jiang DJ, Zhang XH, Guo R, Zhou Z, Deng HW, Li YJ. Effect of asymmetric dimethylarginine on atherogenesis and erythrocyte deformability in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Life Sci. 2007;81:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauser K, da Cunha V, Fitch R, Mallari C, Rubanyi GM. Role of endogenous nitric oxide in progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1679–H1685. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.5.H1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SH, Reddick RL, Piedrahita JA, Maeda N. Spontaneous hypercholesterolemia and arterial lesions in mice lacking apolipoprotein E. Science. 1992;258:468–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1411543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld ME, Polinsky P, Virmani R, Kauser K, Rubanyi G, Schwartz SM. Advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the innominate artery of the ApoE knockout mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2587–2592. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa PA, Milos PM, Gaynor BJ, Breslow JL, Aiello RJ. Estrogen reduces atherosclerotic lesion development in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10022–10027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgin JB, Knowles JW, Kim HS, Smithies O, Maeda N. Interactions between endothelial nitric oxide synthase and sex hormones in vascular protection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:541–548. doi: 10.1172/JCI14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven MO, Hemelaar M, Teerlink T, Kenemans P, van der Mooren MJ. Effects of intranasal versus oral hormone therapy on asymmetric dimethylarginine in healthy postmenopausal women: a randomized study. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangirala RK, Rubin EM, Palinski W. Quantitation of atherosclerosis in murine models: correlation between lesions in the aortic origin and in the entire aorta, and differences in the extent of lesions between sexes in LDL receptor-deficient and apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:2320–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang JJ, Ho HK, Kwan HH, Fajardo LF, Cooke JP. Angiogenesis is impaired by hypercholesterolemia: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation. 2000;102:1414–1419. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.12.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM, Szuba A, Tsao PS, Chan JR, Tangphao O, Blaschke TF, Cooke JP. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): a novel risk factor for endothelial dysfunction: its role in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 1998;98:1842–1847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinitzer A, Seelhorst U, Wellnitz B, Halwachs-Baumann G, Boehm BO, Winkelmann BR, Marz W. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine independently predicts total and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with angiographic coronary artery disease (the Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health study). Clin Chem. 2007;53:273–283. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.076711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel R, Blankenberg S, Lubos E, Lackner KJ, Rupprecht HJ, Espinola-Klein C, Jachmann N, Post F, Peetz D, Bickel C, Cambien F, Tiret L, Munzel T. Asymmetric dimethylarginine and the risk of cardiovascular events and death in patients with coronary artery disease: results from the AtheroGene Study. Circ Res. 2005;97:e53–e59. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000181286.44222.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas R. Pharmacotherapies and their influence on asymmetric dimethylargine (ADMA). Vasc Med. 2005;10(Suppl 1):S49–S57. doi: 10.1191/1358863x05vm605oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovski O, Szumilak D, Nguyen-Khoa T, Ruellan N, Phan O, Lacour B, Descamps-Latscha B, Drueke TB, Massy ZA. The antioxidant N-acetylcysteine prevents accelerated atherosclerosis in uremic apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Kidney Int. 2005;67:2288–2294. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentman ML, Brannstrom T, Westerlund S, Laukkanen MO, Yla-Herttuala S, Basu S, Marklund SL. Extracellular superoxide dismutase deficiency and atherosclerosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1477–1482. doi: 10.1161/hq0901.094248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiper J, Murray-Rust J, McDonald N, Vallance P. S-nitrosylation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates enzyme activity: further interactions between nitric oxide synthase and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13527–13532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212269799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydow K, Munzel T. ADMA and oxidative stress. Atheroscler Suppl. 2003;4:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5688(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope AJ, Karuppiah K, Kearns PN, Xia Y, Cardounel AJ. Role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases in the regulation of endothelial nitric oxide production. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35338–35347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelat M, Dessy C, Massion P, Desager JP, Feron O, Balligand JL. Rosuvastatin decreases caveolin-1 and improves nitric oxide-dependent heart rate and blood pressure variability in apolipoprotein E-/- mice in vivo. Circulation. 2003;107:2480–2486. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065601.83526.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]