Abstract

Activation of synaptic N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor and its intracellular downstream signals in dorsal horn neurons of spinal cord contribute to central sensitization, a mechanism that underlies the development and maintenance of pain hypersensitivity in persistent pain. However, the molecular process of this event is not completely understood. Recently, new studies suggest that peripheral inflammatory insults drive changes in α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor subunit trafficking via N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor-triggered activation of protein kinases in dorsal horn and raise the possibility that such changes might contribute to central sensitization in persistent pain. This review presents current evidence regarding the changes that occur in the trafficking of dorsal horn α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2 under persistent inflammatory pain conditions and discusses potential mechanisms by which such changes participate in the development and maintenance of inflammatory pain.

Inflammation and tissue/nerve injury cause persistent, or chronic, pain, which is characterized by an enhanced response to noxious stimuli (hyperalgesia) and pain in response to normally innocuous stimuli (allodynia). In dorsal horn of the spinal cord, a specific form of synaptic plasticity known as central sensitization is believed to be a mechanism that underlies the development and maintenance of hyperalgesia and allodynia in persistent pain.1,2 An understanding at the molecular level of how central sensitization is induced and maintained in dorsal horn neurons could lead to the development of novel therapeutic targets.

Central sensitization in dorsal horn can be modulated by altering the presynaptic release of neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate and substance P) from the primary afferent terminals and/or by altering the number, types, and properties of postsynaptic membrane receptors (e.g, glutamate receptors) on postsynaptic membranes of dorsal horn neurons.1,2 The α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR) is a glutamate ionotropic receptor that is integral to plasticity and excitatory synaptic transmission at synapses in the central nervous system.3,4 Studies from in vitro and in vivo systems have revealed that changes in postsynaptic membrane trafficking or in synaptic targeting of AMPARs alter excitatory synaptic strength. These changes might contribute to central mechanisms that underlie physiological and pathological processes, such as synaptic plasticity, neurotoxicity, and stroke.5–8 Recent studies have shown that peripheral inflammatory insults drive changes in synaptic AMPAR trafficking in dorsal horn9–12 that might contribute to dorsal horn central sensitization in persistent inflammatory pain.

This review presents current evidence regarding changes that occur in the trafficking of AMPAR subunits GluR1 and GluR2 in dorsal horn neurons after peripheral inflammation and discusses potential mechanisms by which such changes participate in the development and maintenance of inflammatory pain. The role of synaptic AMPAR trafficking in relation to other important mechanisms of activity-dependent sensitization (e.g., Ca2+ influx) also will be discussed.

AMPAR subunits and their expression in dorsal horn

In the central nervous system, AMPARs are assembled from four subunits, GluR1–4.3,4 These subunits are composed of approximately 900 amino acids and share 68–74% amino acid sequence identity13. Each subunit comprises an N-terminal extracellular segment, a ligand-binding domain, a receptor-channel domain, and an intracellular C-terminal domain14. In the ligand-binding domain, two polypeptide segments represent the agonist-recognition sites. This domain also functionally interacts with stargazin, an auxiliary subunit of AMPARs.15 The receptor channel domain consists of four hydrophobic segments (M1–M4). M1, M3, and M4 cross the membrane, whereas M2 faces the cytoplasm as a re-entered loop that forms part of the channel pore.16,17 Thus, among receptor channel domains, M2 controls the flow of ions (including Ca2+) through the AMPAR channel. The C-terminal intracellular domain includes multiple protein phosphorylation sites for various known protein kinases, such as Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), protein kinase C (PKC), and protein kinase A, and several binding sites (or motifs) for various other proteins, such as the scaffolding proteins (e.g., postsynaptic density protein 95) that contain a specific peptidergic domain called PDZ, which is named for the proteins in which the sequence was first identified (Postsynaptic density protein 95/Discs large/Zonula occludens 1).14,17

Functional AMPARs are homomeric or heteromeric tetramers of GluR subunits. Homomeric channels formed from GluR1, GluR3, or GluR4 are Ca2+ permeable and inwardly rectifying [that is, the channel passes current (positive charge) more easily in the inward direction (into the cell)]. Homomeric GluR2 channels, however, express poorly on their own and lack Ca2+ permeability and inward rectification because the GluR2 subunit contains a positively charged arginine at a critical position in the pore-forming M2 segment.4 Incorporation of GluR2 into heteromeric AMPARs strongly reduces Ca2+ permeability and modifies current rectification and macroscopic channel conductance.3

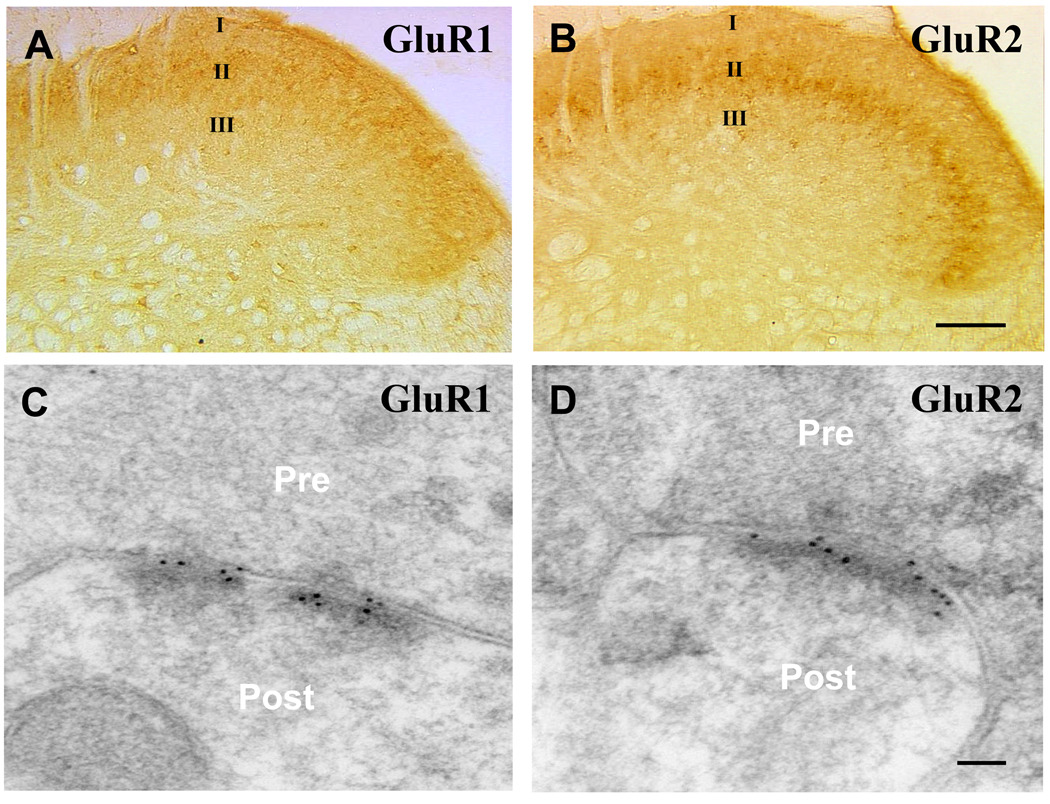

Although all four AMPAR subunits are found within the spinal dorsal horn, GluR1 and GluR2 are the most abundant and are highly concentrated on the postsynaptic neuronal membranes in the superficial dorsal horn (fig. 1).18,19 Thus, under normal conditions, dorsal horn neurons may express one type or a mixture of Ca2+-permeable and Ca2+-impermeable AMPARs.20,21

Fig. 1.

Noxious insults upset the balance of AMPAR subunit recycling in dorsal horn

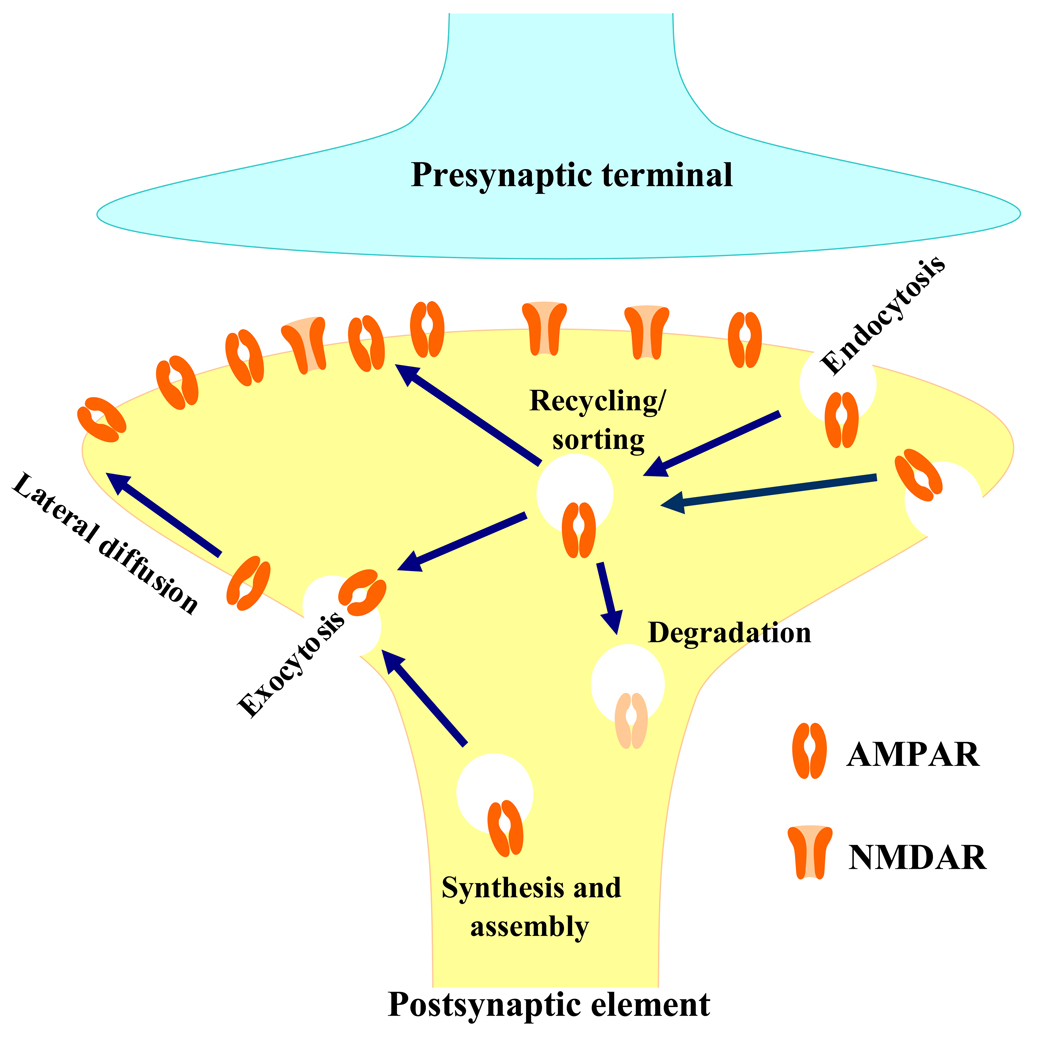

AMPAR subunits are synthesized and assembled in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi of neuronal cell bodies and then inserted into the plasma membrane at the soma. Receptors inserted in the soma may travel to extrasynaptic sites via lateral diffusion.16,21 The subunits can also be synthesized locally in dendrites. Subunit messenger RNA is trafficked out into dendrites via an RNA-protein complex that travels along the cytoskeleton. Messenger RNA can be translated by local polyribosomes in response to neuronal activity.16,17 Proteins translated in the dendrites are processed via dendrite Golgi outposts and travel to extrasynaptic sites. Extrasynaptic receptors diffuse laterally into the synapse, where they are trapped by scaffolding proteins (e.g., Postsynaptic density protein 95).17 Synaptic AMPAR subunits can be recycled back to the intracellular compartment via clathrin-mediated internalization (endocytosis) (fig. 2).17,22 The endocytosed receptors in the endosome are then either recycled back to the plasma membrane via exocytosis or targeted to the lysosome for degradation (fig. 2).17,22 The number of subunits expressed on the synaptic membrane is dependent on the balance between these processes.

Fig. 2.

Using biochemical and morphologic approaches, researchers have shown that peripheral noxious insults upset the balance of AMPAR subunit recycling between membrane and cytosol in dorsal horn. In one study, capsaicin-induced acute inflammation in the colon rapidly and significantly increased the amount of membrane GluR1 protein and correspondingly decreased the level of cytosolic GluR1 in dorsal horn neurons, without affecting total GluR1 or GluR2 protein expression (Table 1).9 In another study, electron microscopy revealed that capsaicin injection into a rat hind paw elevated the density of GluR1-containing AMPARs as well as the ratio of GluR1 to GluR2/3 in postsynaptic membranes contacted by noxious primary afferent terminals that lack substance P.23 In addition, the injection of formalin (an inflammatory agent) into the intraplantar region of a hind paw produced an increase in the level of GluR1 in the plasma membrane of dorsal horn neurons (Table 1).24

Table 1.

GluR1 and GluR2 trafficking in dorsal horn after inflammation

| Model | GluR1 | GluR2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosol | Membrane | Total | Cytosol | Membrane | Total | |

| Capsaicin | ↓ | ↑ | — | — | — | — |

| Formalin | ↓/↑ | ↑ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CFA | ↓ | ↑ | — | ↑ | ↓ | — |

↓: Decrease. ↑: Increase. ↓/↑: Decrease at early and increase at late. —: No change. N/A: Not available. CFA: complete Freund’s adjuvant.

Interestingly, injection of Complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) into a hind paw, which produces long-lasting peripheral inflammation and persistent inflammatory pain, led to changes in subcellular localization of both GluR1 and GluR2 in dorsal horn neurons but did not alter their total expression and distribution in dorsal horn.11,12 The amount of cytosolic GluR2 was markedly increased and the amount of membrane-bound GluR2 was significantly decreased in rat dorsal horn during the maintenance phase of CFA-induced pain hypersensitivity (at least 3 days post-injection) (Table 1).11,12 Conversely, the level of GluR1 was significantly decreased in cytosol and increased in the neuronal membrane 1 day post-CFA (Table 1).11,12 Furthermore, we and others observed that the level of synaptic GluR2 was reduced and that of synaptic GluR1 increased in superficial dorsal horn (laminae I-II) neurons 1 day post-CFA injection.10,12 However, none of these studies showed any changes in either GluR1 or GluR2 during the development phase (2 h post-CFA).10,12 This evidence implies that acute (e.g., capsaicin) and persistent (e.g., CFA) inflammatory insults may induce distinctly different changes in dorsal horn AMPAR subunit trafficking.

Potential mechanisms of AMPAR trafficking regulation in inflammatory pain

The molecular mechanisms by which peripheral noxious insults alter dorsal horn AMPAR subunit trafficking are unclear, but they might be associated with nociceptive information-induced phosphorylation of the serine (Ser) residues of both GluR1 and GluR2 C-termini in spinal cord. Three major phosphorylation sites on the Ser residues of the GluR1 C terminus have been identified: Ser845, Ser831, and Ser818. Ser845 is specifically phosphorylated by protein kinase A,25 Ser831 by PKC and CaMKII,25,26 and Ser818 by PKC.27 The change in phosphorylation status of these three sites directly impacts electrophysiological properties, subunit composition, and/or expression of synaptic AMPARs. Protein kinase A phosphorylation of GluR1 at Ser845 increases the channel open probability of AMPARs and peak amplitude of their currents, stabilizes GluR1 in the plasma membrane, enhances the incorporation of GluR1-containing AMPARs into the synaptic membrane, and decreases AMPAR internalization.28–30 Phosphorylation of GluR1 on Ser831 (the PKC/CaMKII site) increases the signal channel conductance of synaptic AMPARs,31 but does not appear to influence membrane insertion. Rather, CaMKII activation drives GluR1-containing AMPARs to synapses by a mechanism that requires the binding of GluR1 to its scaffolding protein.32 In contrast, phosphorylation of GluR1 Ser818 by PKC might be involved in promoting synaptic GluR1 membrane insertion, as preventing Ser818 phosphorylation blocks PKC-driven synaptic incorporation of GluR1.27 However, how these phosphorylation sites promote GluR1 membrane insertion is still unknown.

Capsaicin or CFA injection increases phosphorylation at Ser845 and Ser831 of GluR1 in dorsal horn neurons.33–35 Phosphorylation at these serine residues might be involved in dorsal horn GluR1 membrane insertion in response to acute (capsaicin) or persistent (CFA) inflammatory insults. To confirm this conclusion, it will be very interesting to investigate how targeted mutation of Ser845, Ser831, and Ser818 affects inflammatory insult-induced changes in dorsal horn neuronal synaptic GluR1 trafficking as well as inflammation-induced pain hypersensitivity.

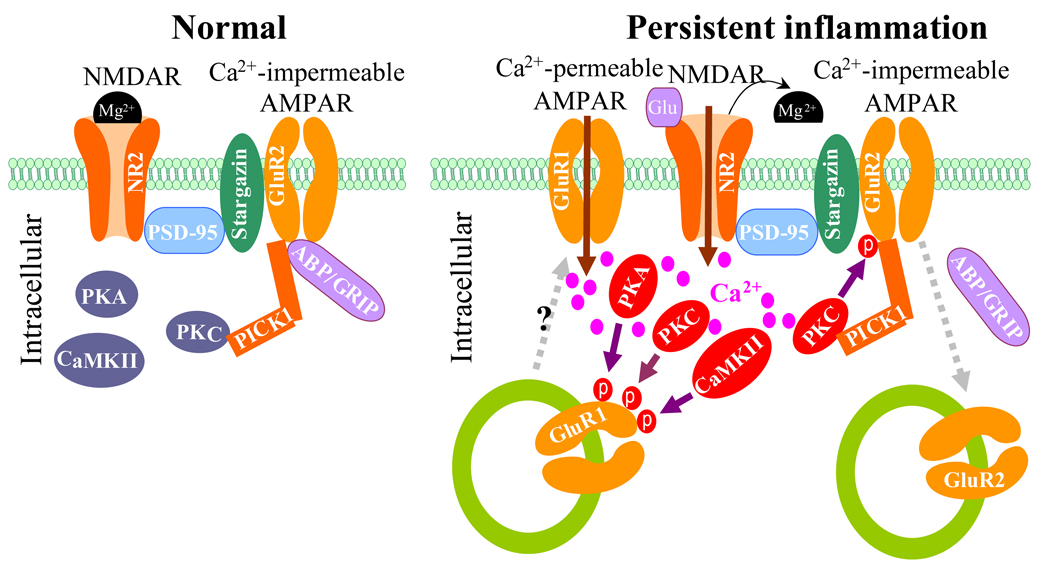

GluR2 contains a PDZ-binding motif at its C terminus that interacts with the PDZ domains of two postsynaptic scaffolding proteins, protein interacting with C kinase 1 (PICK1) and AMPAR-binding protein (ABP)/glutamate receptor-interacting protein (GRIP). ABP/GRIP anchors and stabilizes GluR2 at the synaptic membrane,36–38 whereas PICK1 recruits PKC to ABP/GRIP-GluR2 complexes, leading to phosphorylation of GluR2 at Ser880 (fig. 3).39–41 Evidence from cultured brain neurons and human embryonic kidney 293 cells showed that GluR2 phosphorylation at Ser880 by PKC disrupted GluR2 binding to ABP/GRIP, but not binding to PICK1, and promoted GluR2 internalization.39,40,42,43

Fig. 3.

Our recent evidence indicates that N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDAR)-triggered PKC phosphorylation at GluR2 Ser880 is responsible for GluR2 internalization in dorsal horn neurons after persistent inflammation. In dorsal horn of normal rat, GluR2 binds to both GRIP1 and PICK1, whereas PICK1 also interacts with PKCα (fig. 3).12 NMDAR and PKC activation significantly increased the level of GluR2 phosphorylation at Ser880 and reduced surface expression of GluR2 in cultured dorsal horn neurons.12 In contrast, activation of AMPARs or group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors had no effect.12 In an in vivo study, CFA injection into the hind paw of mice and rats induced GluR2 phosphorylation at Ser880, reduced the binding affinity of GluR2 to GRIP1, and promoted Glu2 internalization in dorsal horn neurons during the maintenance phase.12 These effects were attenuated by an intrathecally administered NMDAR antagonist or PKC inhibitor.12 More importantly, targeted mutation of GluR2 phosphorylation site Ser880 attenuated CFA-induced GluR2 internalization in dorsal horn neurons.12 These findings suggest that dorsal horn NMDARs are activated and that Ca2+ could flow inward through NMDAR channels during peripheral inflammation (fig. 3). The increase in intracellular Ca2+ would promptly activate PKC to phosphorylate GluR2 at Ser880; this phosphorylation would disrupt GluR2 binding to ABP/GRIP and promote GluR2 internalization at postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons (fig. 3). This conclusion is strongly supported by evidence that NMDAR-triggered GluR2 internalization in vitro requires Ca2+ influx directly through NMDARs.44,45 In addition, there is a physical link between AMPARs and NMDARs or PKC at synapses in spinal cord dorsal horn (fig. 3).12 Postsynaptic density protein 95 binds to both NMDAR subunits NR2A/2B and stargazin, whereas stargazin interacts with GluR1/2/4. It appears that AMPARs are physically coupled to NMDAR complex by a postsynaptic density protein 95-stargazin linkage. PICK1 recruits PKCα to GluR2 in dorsal horn neurons.12 Thus, this physical coupling provides a molecular basis by which Ca2+ can enter the cell through the NMDAR channel and promptly activate intracellular protein kinases (e.g., PKC) that can then phosphorylate GluR1 and GluR2 in dorsal horn neurons (fig. 3). Taken together, the evidence clearly supports the premise that GluR2 phosphorylation at Ser880 triggered by NMDAR/PKC activation contributes to CFA-induced dorsal horn GluR2 internalization during the maintenance phase.

In addition to PICK1 and ABP/GRIP, other proteins that interact with the GluR2 C-terminal may also be involved in changes of synaptic GluR2 trafficking in dorsal horn neurons in inflammatory pain. For example, N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein binds to GluR2 and helps to maintain the synaptic expression of GluR2-containing AMPARs. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein also displaces PICK1 from the PICK1-GluR2 complex and thereby facilitates the delivery to or stabilization of GluR2 at the plasma membrane. CFA injection has been shown to reduce N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein expression in spinal cord.10 This reduction might also contribute to CFA-induced dorsal horn GluR2 internalization.

AMPAR trafficking and central sensitization in inflammatory pain

Based on the evidence presented thus far, inflammation-induced changes in AMPAR subunit trafficking at postsynaptic membranes of dorsal horn neurons might be involved in the maintenance of central sensitization in persistent inflammatory pain (fig. 3). CFA-induced time-dependent changes in GluR2 internalization and GluR1 membrane insertion in dorsal horn neurons correlate with the time course of changes in CFA-induced pain hypersensitivity during the maintenance period,11,12 indicating that these changes may be markers for pain hypersensitivity during the maintenance of persistent inflammatory pain. We have reported that activation of spinal cord NMDARs and PKC induces dorsal horn GluR2 internalization during the maintenance period of CFA-induced inflammatory pain.12 Given that spinal cord NMDARs and PKC are critical for the maintenance of chronic inflammatory pain,46 dorsal horn GluR2 internalization might underlie the mechanism by which activation of NMDARs and PKC maintains inflammatory pain (fig. 3). Indeed, preventing dorsal horn GluR2 internalization through targeted mutation of the GluR2 PKC phosphorylation site impairs CFA-evoked mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia during the maintenance period.12 Moreover, CFA-induced GluR2 internalization and GluR1 membrane insertion lead to an increase in AMPAR Ca2+ permeability in dorsal horn neurons (fig. 3). This phenomenon was illustrated by electrophysiological patch-clamp recordings of rat dorsal horn neurons. This experiment showed that the number of Ca2+-permeable AMPARs in the superficial dorsal horn was significantly increased during the maintenance phase of CFA-induced persistent inflammatory pain.10,12,47 The increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration should initiate or potentate a variety of Ca2+-dependent intracellular cascades that are associated with the mechanisms of pain hypersensitivity during inflammatory pain states. Thus, GluR2 internalization and GluR1 membrane insertion in dorsal horn may participate in the maintenance of CFA-induced pain hypersensitivity by increasing synaptic AMPAR Ca2+ permeability. The latter leads to more increases in intracellular Ca2+ concentration, which further enhances activation of Ca2+-dependent intracellular signals (e.g., PKC, CaMKII, and protein kinase A activation) in dorsal horn. This positive feedback that occurs through alteration of AMPAR subunit trafficking and increases in Ca2+-permeable AMPARs in dorsal horn neurons could be crucial for the maintenance of pain hypersensitivity in persistent inflammatory pain (fig. 3).

In summary, new research has brought to light distinct changes that occur in dorsal horn AMPAR subunit trafficking in acute and persistent inflammatory pain. Our recent work showed that peripheral noxious input induced by incision pain did not produce a significant change in dorsal horn AMPAR subunit trafficking (data not shown). These findings suggest that different peripheral nociceptive insults may induce distinct changes in spinal AMPAR subunit trafficking. It will be very important to further characterize AMPAR subunit trafficking in dorsal horn under other persistent pain conditions (such as neuropathic pain) and to investigate other potential molecular mechanisms to fully understand the role of spinal AMPAR trafficking in the central sensitization that underlies persistent pain. Such studies will not only provide new insight into the central mechanisms of persistent pain but also might point the way to a new strategy for the prevention and treatment of persistent pain.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Claire Levine, M.S., E.L.S., Manager of Editorial Services, in the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA, for her editorial assistance.

Support: This work was supported by grants R01-NS058886 and R21-NS057343 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, and by the Blaustein Pain Research Fund from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Footnotes

Summary Statement: This review highlights recent findings regarding the changes in dorsal horn α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor trafficking in persistent inflammatory pain and discusses how such changes participate in the development and maintenance of inflammatory pain.

References

- 1.Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization and LTP: Do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latremoliere A, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J Pain. 2009;10:895–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnashev N, Monyer H, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Divalent ion permeability of AMPA receptor channels is dominated by the edited form of a single subunit. Neuron. 1992;8:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell JD, Park E, Ai J, Baker AJ. PICK1-mediated GluR2 endocytosis contributes to cellular injury after neuronal trauma. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1665–1680. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon RM, Mellor JR, Hanley JG. PICK1-mediated glutamate receptor subunit 2 (GluR2) trafficking contributes to cell death in oxygen/glucose-deprived hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14230–14235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901203200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahajan SS, Ziff EB. Novel toxicity of the unedited GluR2 AMPA receptor subunit dependent on surface trafficking and increased Ca2+-permeability. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isaac JT, Ashby M, McBain CJ. The role of the GluR2 subunit in AMPA receptor function and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galan A, Laird JM, Cervero F. In vivo recruitment by painful stimuli of AMPA receptor subunits to the plasma membrane of spinal cord neurons. Pain. 2004;112:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katano T, Furue H, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Tagaya M, Watanabe M, Yoshimura M, Ito S. N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein (NSF) is involved in central sensitization in the spinal cord through GluR2 subunit composition switch after inflammation. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:3161–3170. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park JS, Yaster M, Guan X, Xu JT, Shih MH, Guan Y, Raja SN, Tao YX. Role of spinal cord alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors in complete Freund's adjuvant-induced inflammatory pain. Mol Pain. 2008;4:67. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JS, Voitenko N, Petralia RS, Guan X, Xu JT, Steinberg JP, Takamiya K, Sotnik A, Kopach O, Huganir RL, Tao YX. Persistent inflammation induces GluR2 internalization via NMDA receptor-triggered PKC activation in dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3206–3219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4514-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collingridge GL, Isaac JT, Wang YT. Receptor trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:952–962. doi: 10.1038/nrn1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song I, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptors during synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:578–588. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomita S, Shenoy A, Fukata Y, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Stargazin interacts functionally with the AMPA receptor glutamate-binding module. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Man HY, Ju W, Ahmadian G, Wang YT. Intracellular trafficking of AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1526–1534. doi: 10.1007/PL00000637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd JD, Huganir RL. The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerr RC, Maxwell DJ, Todd AJ. GluR1 and GluR2/3 subunits of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor are associated with particular types of neurone in laminae I-III of the spinal dorsal horn of the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:324–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu CR, Hwang SJ, Phend KD, Rustioni A, Valtschanoff JG. Primary afferent terminals in spinal cord express presynaptic AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9522–9529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09522.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelman HS, Allen TB, MacDermott AB. The distribution of neurons expressing calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in the superficial laminae of the spinal cord dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2081–2089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02081.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartmann B, Ahmadi S, Heppenstall PA, Lewin GR, Schott C, Borchardt T, Seeburg PH, Zeilhofer HU, Sprengel R, Kuner R. The AMPA receptor subunits GluR-A and GluR-B reciprocally modulate spinal synaptic plasticity and inflammatory pain. Neuron. 2004;44:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos SD, Carvalho AL, Caldeira MV, Duarte CB. Regulation of AMPA receptors and synaptic plasticity. Neuroscience. 2008;158:105–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsson M, Broman J. Translocation of GluR1-containing AMPA receptors to a spinal nociceptive synapse during acute noxious stimulation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7084–7090. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5749-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pezet S, Marchand F, D'Mello R, Grist J, Clark AK, Malcangio M, Dickenson AH, Williams RJ, McMahon SB. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is a key mediator of central sensitization in painful inflammatory conditions. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4261–4270. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5392-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche KW, O'Brien RJ, Mammen AL, Bernhardt J, Huganir RL. Characterization of multiple phosphorylation sites on the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit. Neuron. 1996;16:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mammen AL, Kameyama K, Roche KW, Huganir RL. Phosphorylation of the alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole4-propionic acid receptor GluR1 subunit by calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32528–32533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehm J, Kang MG, Johnson RC, Esteban J, Huganir RL, Malinow R. Synaptic incorporation of AMPA receptors during LTP is controlled by a PKC phosphorylation site on GluR1. Neuron. 2006;51:213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banke TG, Bowie D, Lee H, Huganir RL, Schousboe A, Traynelis SF. Control of GluR1 AMPA receptor function by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 2000;20:89–102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00089.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Man HY, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Huganir RL. Regulation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor trafficking through PKA phosphorylation of the Glu receptor 1 subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3579–3584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611698104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oh MC, Derkach VA, Guire ES, Soderling TR. Extrasynaptic membrane trafficking regulated by GluR1 serine 845 phosphorylation primes AMPA receptors for long-term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:752–758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derkach V, Barria A, Soderling TR. Ca2+/calmodulin-kinase II enhances channel conductance of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate type glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3269–3274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi Y, Shi SH, Esteban JA, Piccini A, Poncer JC, Malinow R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science. 2000;287:2262–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang L, Wu J, Zhang X, Lin Q, Willis WD. Increased phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of spinal cord α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptor in rats following intradermal injection of capsaicin. Neuroscience. 2003;122:237–245. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00526-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang L, Wu J, Lin Q, Willis WD. Protein kinases regulate the phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptors of spinal cord in rats following noxious stimulation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;118:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Y, Sun YN, Wu X, Sun Q, Liu FY, Xing GG, Wan Y. Role of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) receptor subunit GluR1 in spinal dorsal horn in inflammatory nociception and neuropathic nociception in rat. Brain Res. 2008;1200:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong H, O'Brien RJ, Fung ET, Lanahan AA, Worley PF, Huganir RL. GRIP: A synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein that interacts with AMPA receptors. Nature. 1997;386:279–284. doi: 10.1038/386279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong H, Zhang P, Song I, Petralia RS, Liao D, Huganir RL. Characterization of the glutamate receptor-interacting proteins GRIP1 and GRIP2. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6930–6941. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-06930.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong H, Zhang P, Liao D, Huganir RL. Characterization, expression, and distribution of GRIP protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dev KK, Nakanishi S, Henley JM. The PDZ domain of PICK1 differentially accepts protein kinase C-alpha and GluR2 as interacting ligands. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41393–41397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404499200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez JL, Khatri L, Chang C, Srivastava S, Osten P, Ziff EB. PICK1 targets activated protein kinase Cα to AMPA receptor clusters in spines of hippocampal neurons and reduces surface levels of the AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunit 2. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5417–5428. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05417.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Staudinger J, Lu J, Olson EN. Specific interaction of the PDZ domain protein PICK1 with the COOH terminus of protein kinase C-α. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32019–32024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung HJ, Xia J, Scannevin RH, Zhang X, Huganir RL. Phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 differentially regulates its interaction with PDZ domain-containing proteins. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7258–7267. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuda S, Mikawa S, Hirai H. Phosphorylation of serine-880 in GluR2 by protein kinase C prevents its C terminus from binding with glutamate receptor-interacting protein. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1765–1768. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.731765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwakura Y, Nagano T, Kawamura M, Horikawa H, Ibaraki K, Takei N, Nawa H. Nmethyl-d-aspartate-induced α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid (AMPA) receptor down-regulation involves interaction of the carboxyl terminus of GluR2/3 with Pick1. Ligand-binding studies using Sindbis vectors carrying AMPA receptor decoys. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40025–40032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tigaret CM, Thalhammer A, Rast GF, Specht CG, Auberson YP, Stewart MG, Schoepfer R. Subunit dependencies of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptorinduced α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor internalization. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1251–1259. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basbaum AI, Woolf CJ. Pain. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R429–R431. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vikman KS, Rycroft BK, Christie MJ. Switch to Ca2+-permeable AMPA and reduced NR2B NMDA receptor-mediated neurotransmission at dorsal horn nociceptive synapses during inflammatory pain in the rat. J Physiol. 2008;586:515–527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]