Abstract

The high prevalence of contaminated cell cultures suggests that viral contaminations might be distributed among cultures. We investigated more than 460 primate cell lines for Epstein-Barr (EBV), hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus I and II (HTLV-I/-II), and squirrel monkey retrovirus (SMRV) infections for risk assessment. None of the cell lines were infected with HCV, HIV-1, or HTLV-I/-II. However, one cell line displayed reverse transcriptase activity. Thirty-nine cell lines harbored EBV DNA sequences. Studies on the lytic phase of EBV revealed that five cell lines produce EBV particles and six further cell lines produced EBV upon stimulation. One cell line contained an integrated HBV genome fragment but showed no virus production. Six cell lines were SMRV-infected. Newly established cell lines should be tested for EBV infections to detect B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCL). B-LCLs established with EBV from cell line B95-8 should be tested for SMRV infections.

1. Introduction

Human primary cell cultures and cell lines have become fundamental tools for basic research in numerous life science faculties as well as for the production of bioactive reagents in biomedicine and biotechnology. They are already used for several decades and frozen cell cultures or blood and tissue samples obtained many years ago can be found in numerous laboratories. As known from experience in the transfusion and transplantation medicine, human cells can harbor a number of different human pathogens and conveyed a potential risk for the recipients to become infected before extensive screenings of the material were accomplished. In particular, human pathogenic viruses like human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type I and II (HTLV-I and -II), and hepatitis viruses, for example, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), are found in human donor and patient material [1]. Cell lines were usually established from patient material which might similarly be infected with those viruses or perhaps with viruses linked to specific tumors, for example, human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8) or novel types of papilloma viruses [2]. A considerable percentage of cell lines was established before viral contaminations had been routinely assayed or even before those viruses had been discovered. Additionally, the risk of emerging pathogens has to be kept under constant review [3].

Indeed, some cell lines are known to harbor human pathogenic viruses, among them the well-known and widely distributed HeLa cell line which contains the human papilloma virus integrated into its genome [4]. Besides the infection of the primary material which may be traced back to the donor, contaminations of cell cultures can also be introduced secondarily by laboratory personnel or from other infected cells when handled simultaneously. Such means of infection are much more likely, as similar problems were shown for mycoplasma contaminations (an incidence of ca. 25% has been reported) and cross contaminations of cell cultures (ca. 15%) [5]. This type of infection with transmissible viruses might be true for the contamination with squirrel monkey retrovirus (SMRV), which was detected in some human and animal cell lines; sequences of the virus were shown to be present in interferon-α preparations produced by the human Burkitt lymphoma cell line NAMALWA [6, 7].

Human and animal cells themselves represent no increased risk during routine cell culture. But an infection of the cells with human pathogenic viruses or bacteria increases the potential risk of a cell culture. Although the probability of the unintentional establishment of a cell line which is infected with a high-risk virus is extremely low, primary cells and cell cultures of unknown origin should be regarded as potentially harmful and are categorized as risk group 2, at least until the infection status of the donor or the cells is clearly determined. Whereas some viruses can be easily propagated in continuous cell lines (e.g., human retroviruses), propagation of other viruses depends on the microenvironment or maturation of the otherwise permissive cells. Additionally, some viruses exhibit a latent or cryptic infection cycle, during which no active viruses are produced (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), proviruses of retroviruses). However, the latent status can be switched to the productive lytic cycle by certain inducers, or constantly low replication rates can be found [8].

In this report, we describe the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Southern and Western blotting for the detection of latent and active forms of the human pathogenic viruses (EBV, HBV, HCV, HIV-1, HTLV-I and -II), SMRV, and retroviruses in general in a large panel of continuous primate cell lines to determine the potential risk for handling these cell lines. Regarding EBV, the inducibility of the lytic cycle was investigated by treatment of the latently infected cell lines with the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and sodium butyrate (Na-butyrate).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Culture of Cell Lines

The continuous cell lines were provided for accessioning to the cell lines bank by the original or secondary investigators [9]. Cell lines were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of air containing 5% CO2. The basic growth media (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) were supplemented with 10%–20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany). For growth factor-dependent cell lines, specific growth factors or conditioned media containing growth factors were added. No antibiotics were added to the cultures. All cell lines were free of mycoplasma and other bacterial, yeast, and fungi contaminations as tested by PCR and microbiological growth assays [10]. The authenticity of the cell lines was determined by DNA typing [11]. For the induction of the lytic cycle of EBV infection, PCR-positive cell lines were treated for 3 days with 10−7 M TPA (Sigma) and 3 mM Na-butyrate (Sigma).

2.2. Western Blotting Analysis

A total of 1 × 106 cells were pelleted and washed with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 30 μL ice-cold protease inhibitor buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, and 100 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and boiled for 10 minutes after addition of 30 μL 2 × SDS gel-loading buffer containing 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol 2% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE. Blotting and staining conditions were as described previously [12]. BZLF1 protein was detected using the mouse anti-ZEBRA antibody (DakoCytomation, Hamburg, Germany) diluted 1 : 100 in PBS and 5% FBS.

2.3. RT-ELISA

Most of the cell lines were analyzed for general infections with retroviruses applying an ELISA. Briefly, using 5 mL cell free culture supernatant, retrovirus particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g or by polyethylene glycol precipitation and subsequent centrifugation at 800 × g. The pellets were analyzed applying the Reverse Transcriptase Assay, nonradioactive, from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). In this assay, digoxigenin- and biotin-labeled desoxyuridine-triphosphates are incorporated in the presence of viral reverse transcriptase during the synthesis of a DNA strand along a synthetic target of single-stranded DNA molecules. The newly synthesized DNA is trapped on streptavidin-coated microtiter plates and subsequently detected immunologically by binding of peroxidase-labeled antidigoxigenin antibodies and visualized by color development and finally quantified by measuring the absorbance with an ELISA reader [13]. Two different buffers were used to detect Mg2+-dependent RT as well as Mn2+-dependent RT of mammalian C-type retroviruses.

2.4. In Situ Lysing Gel Analysis

Episomal and linear forms of EBV DNA were distinguished by horizontal gel electrophoresis according to Gardella et al. [14]. After electrophoresis, the separated DNA was blotted onto nylon filters (see Southern blot analysis) and the DNA was hybridized with a 32P labeled ca. 37 kb DNA fragment of the 5′-region of EBV (cM-Sal A) [15].

2.5. Southern Blot Analysis

Genomic DNA of cell lines or DNA from EBV was extracted and purified using the PCR High Pure DNA kit from Roche. Fifteen μg of genomic DNA or EBV DNA from 24 mL supernatant of the B95-8 cell line were digested with 150 U XhoI restriction enzyme over night. After electrophoresis, the separated DNA was blotted onto a nylon membrane and hybridized with various radioactively labeled cosmid probes from the EBV genome [15] as described earlier [16]. Probes for the 5′- and 3′-region of the linear EBV genome were prepared by PCR. An 894 bp fragment of the 5′-region was amplified using the forward primer F-EBV1 (5′-AGG CAT TTA CGG TTA GTG TG-3′) and the reverse primer R-EBV1 (5′-CGG TCA GGA TAG CAA GAA T-3′). PCR was carried out with 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 52°C, and 1 minute at 72°C with hotstart Taq (TaKaRa, Lonza, Verviers, Belgium). A 619 bp fragment of the 3′-region of the linear EBV genome was amplified using the forward primer F-EBV2 (5′-ATC CTC AGG GCA GTG TGT CAG-3′) and the reverse primer R-EBV2 (5′-CAA GCC GCA GCG ACT TTC-3′). PCR was carried out with 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 59°C, and 1 minute at 72°C with hotstart Taq. The PCR fragments were isolated from the gels and cloned into pGEM-T-easy vectors (Invitrogen). Aliquots of the clear lysates were labeled with 32P by nick translation and hybridized to the Southern blots. Signals were detected with a phosphor imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.6. PCR Assays

PCR or RT-PCR was applied for the detection of specific DNA or RNA sequences of the human pathogenic viruses EBV, HBV, HCV, HHV-8, HIV-1, HTLV-I and -II, and SMRV. DNA sequences integrated into the cellular genome (proviruses) and episomal DNA of EBV and HHV-8 were detected using the PCR amplification method. DNA from cell lines was isolated applying the High Pure PCR Template Preparation kit from Roche. Specific oligonucleotide pairs from the gag region of HIV-1 (SK 38 and SK 39) [17], the pol region of HLTV-I/-II (SK 110 and SK 111) [18], the gag and env region of SMRV (F-SMRV-env, R-SMRV-env and F-SMRV-gag, R-SMRV-gag), from the EB2 (BMLF1) gene of EBV (TC 70 and TC 72) [19], and the putative minor capsid protein gene of HHV-8 (F- and R-HHV-8) [20] were used with the appropriate annealing temperatures in the PCR reaction (Table 1). The hot start PCR was either carried out by denaturing the reaction-mix which contains no Taq-polymerase for 7 minutes at 94°C, subsequently adding the Taq-polymerase mix (1 U/reaction) during the following cycle step at 72°C for 3 minutes, annealing for 2 minutes at the appropriate temperature, and amplification at 72°C for 10 minutes, or by using hotstart Taq-polymerase with initial cycles according to the manufacturer's recommendations. After the initial cycle, 35 cycles were run at 95°C for 30 seconds, template specific annealing temperature for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute plus 2 seconds extension for each cycle. The amplified products were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide intercalation.

Table 1.

Primer sequences and PCR product sizes of wild type and internal control DNAs.

| ABL: | ||

| F-ABL-A2: | 5′-TGA CTT TGA GCC TCA GGG TCT GAG TGA AGC C-3′ | |

| R-ABL-A3: | 5′-CCA TTT TTG GTT TGG GCT TCA CAC CAT TCC-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 70°C | |

| Reference sequence (mRNA): | GenBank:NM_007313 | |

| Reference sequence (genomic DNA): | GenBank:U07563 | |

| Nucleotide position (mRNA): | 159–374 | |

| Nucleotide position (genomic DNA): | 49914–50692 | |

| RT-PCR product: | 216 bp | |

| PCR product: | 779 bp | |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa ExTaq HS (Lonza) | |

| EBV: | ||

| F-EBV (TC-70): | 5′-CTT GGA GAC AGG CTT AAC CAG ACT CA-3′ | |

| R-EBV (TC-72): | 5′-CCA TGG CTG CAC CGA TGA AAG TTA T-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 60°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: V01555 | Nucleotide positions: 83520–83784 |

| PCR product (wild type): | 265 bp | PCR product (internal control): 445 bp |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa Taq HS (Lonza) | |

| HBV: | ||

| F-HEPB: | 5′-AAG CTG TGC CTT GGG TGG CTT-3′ | |

| R-HEPB: | 5′-CGA GAT TGA GAT CTT CTG CGA C-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 55°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: NC_003977 | Nucleotide positions: 1874–2436 |

| PCR product (wild type): | 563 bp | PCR product (internal control): 906 bp |

| Taq polymerase: | BioTherm Taq polymerase (Gene Craft, Lüdinghausen, Germany) | |

| HCV: | ||

| F-HCV: | 5′-GCC ATG GCG TTA GTA TGA GT-3′ | |

| R-HCV: | 5′-RTG CAC GGT CTA CGA GAC CT-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 55°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: NC_004102 | Nucleotide positions: 82–340 |

| PCR product (wild type): | 259 bp | PCR product (internal control): 452 bp |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa ExTaq HS (Lonza) | |

| HHV-8: | ||

| F-HHV-8: | 5′-AGC CGA AAG GAT TCC ACC AT-3′ | |

| R-HHV-8: | 5′-TCC GTG TTG TCT ACG TCC AG-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 56°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: NC_009333 | Nucleotide positions: 47386–47618 |

| PCR product: | 232 bp | |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa ExTaq HS (Lonza) | |

| HIV-1: | ||

| F-HIV (SK38): | 5′-ATA ATC CAC CTA TCC CAG TAG GAG AAA T-3′ | |

| R-HIV (SK39): | 5′-TTT GGT CCT TGT CTT ATG TCC AGA ATG C-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 50°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: NC_001802 | Nucleotide positions: 1090–1204 |

| PCR product (wild type): | 114 bp | PCR product (internal control): 403 bp |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa Taq HS (Lonza) | |

| HTLV-I/-II: | ||

| F-HTLV (SK110): | 5′-CCC TAC AAT CCA ACC AGC TCM G-3′ | |

| 5′-CCT TAC AAT CCA ACC AGC TCA G-3′ | ||

| 5′-CCA TAC AAC CCC ACC AGC TCA G-3′ | ||

| R-HTLV (SK111): | 5′-GTG RTG GAT TTG CCA TCG GGT T-3′ | |

| 5′-GTG GTG AAG CTG CCA TCG GGT T-3′ | ||

| Annealing temperature: | 60°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: NC_001436 | Nucleotide positions: 4384–4569 |

| PCR product (wild type): | 186 bp | PCR product (internal control): 405 bp |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa Taq HS (Lonza) | |

| SMRV: | ||

| F-SMRV-env: | 5′-GGC GGA CCC CAA GAT GCT GTG-3′ | |

| R-SMRV-env: | 5′-TGG GCT AGG CTG GGG TTG GAG ATA-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 67°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: M23385 | Nucleotide positions: 6857–7053 |

| PCR product: | 197 bp | |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa Ex Taq HS (Lonza) | |

| F-SMRV-gag: | 5′-TCA GAG CCC ACC GAG CCT ACC TAC-3′ | |

| R-SMRV-gag: | 5′-CAG CGC AGC ACG AGA CAA GAA AA-3′ | |

| Annealing temperature: | 67°C | |

| Reference sequence: | GenBank: M23385 | Nucleotide positions: 1737–1922 |

| PCR product: | 186 bp | |

| Taq polymerase: | TaKaRa Taq HS (Lonza) | |

The active form of HBV was tested by organic extraction of DNA from 5 mL supernatant of the cell lines after enrichment of particles by ultracentrifugation (15 minutes at 100,000 × g). PCR was carried out using forward and reverse primers from the conserved region of the precore/core protein gene to detect the different subtypes of HBV (Table 1). For the detection of the hepatitis B surface antigen coding region in cell line HEP-3B, a second primer pair was applied, consisting of the forward primer F-HBV-3 (5′-CAA GAT TCC TAT GGG AGT GGG CCT-3′) and R-HBV-4 (5′-CTC TGC CGA TCC ATA CTG CGG AAC-3′).

For HCV detection, total RNA was isolated from cells by organic extraction with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen) as described by the manufacturer. Five μg were reverse transcribed using random primers and SuperScript reverse transcriptase according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). The equivalent of 1 μg RNA was used for RT-PCR. The amplification was carried applying primers from the 5′ untranslated region (5′-UTR) of HCV [21] (Table 1).

In all PCR runs appropriate positive, negative, and internal controls were integrated in parallel reactions. As positive control for HIV, a plasmid containing the gag and pol region of HIV-1 was used. This was kindly provided by Dr. H. Hauser (Helmholtz Center for Infection Research, Braunschweig, Germany). As positive control for HTLV, we applied genomic DNA from the human T leukemia cell line MT-1. This cell line is infected with HTLV-I [22]. Regarding EBV and HHV-8, genomic DNA of the cell lines RAJI and CRO-AP2 were used as positive control DNA, respectively [20]. Active HBV reference plasma (subtypes ad and ay) were applied to establish the PCR procedure and used as positive controls. The plasma samples were obtained from the German National Reference Center for Virus Hepatitis (Göttingen, Germany). A plasmid containing the HCV 5′-UTR was kindly provided by Professor Dr. M. Roggendorf from the National Reference Center for Hepatitis C (Essen, Germany).

Except for HHV-8 and SMRV, internal control DNA for each of the PCR assays was constructed starting from the PCR products of the positive control DNA. In general, DNA fragments were cloned into the PCR products to retain the target sequences of the respective primer pairs, but to obtain a PCR product which is significantly longer than the original PCR product of the wild type sequence. For HIV and HTLV, a 250 bp HCV positive control PCR fragment was inserted into the HIV and HTLV fragments, according to the “gene splicing by overlap extension” method described by Telenti et al. [23].

For HBV, the PCR product of the positive control reaction was ligated into the pGEM-T vector and a 445 bp fragment was excised from the insert employing the restriction enzyme BglII. A 788 bp DNA fragment was isolated after digestion of the pGEM vector applying MboI. Both restriction enzymes produce the same sticky end sequences. Thus, the shortened and linearized vector containing the HBV PCR product ends can be ligated with the pGEM restriction fragment, transformed into E. coli, and the resulting plasmid can be used as internal control DNA for HBV. The fragment is 343 bp longer than the wild type sequence. A similar strategy was applied for HCV. The PCR product from the positive control DNA was ligated into the pGEM-T vector and a 187 bp fragment was excised using the restriction enzyme SmaI. pHSSE-1 was digested with RsaI and a 379 bp fragment was extracted from the gel. Blunt-end ligation of the two DNA sequences and transformation into E. coli produced a plasmid containing a DNA sequence which can be amplified with the HCV primer and is 192 bp longer than the wild type DNA.

2.7. Interphase FISH

One million cells were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 minutes. The pellet was washed with 5 mL PBS, centrifuged again at 200 × g for 5 minutes, and the cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS. One hundred μl of the cell suspension were centrifuged onto acid washed slides using a cytospin centrifuge. The slides were air-dried and the cells were fixed in a mixture of methanol and acetic acid (3 : 1) for 30 minutes in the cold. The fixation step was repeated twice. Then the slides were air-dried for ca. 10 minutes. The samples were dehydrated with an ethanol series (70%, 70%, 90%, 90%, and 100%, each for 2 minutes). The slides were again air-dried for 10 minutes and processed further or stored at −20°C with desiccant.

The EBV cosmid DNA was labeled with Cy3 or Spectrum Green (Vysis, Stuttgart, Germany) by nick-translation (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Ca. 40 ng of the labeled probe was added to 1 μg of human Cot DNA (Roche) and ethanol precipitated. The pellet was resuspended in 10 μl Hybrizol VII (Qbiogene, Heidelberg, Germany), placed on the slide, covered with a cover slip, and sealed with rubber cement. The preparations were denatured at 80°C on a heating plate and the subsequent hybridization was carried out at 37°C over night.

Slides were washed in 2 × SSC at room temperature for 1 minute, 3 times in 50% formamide/50% 2 × SSC at 40°C for 3 minutes, 3 times in 2 × SSC at 40°C for 2 minutes, and 5 minutes at room temperature in 4 × SSC. Slides were mounted with Vecta-Shield containing 1 μg/mL counterstain 1 (Hoechst, Frankfurt, Germany) and evaluated with a fluorescence microscope.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Detection of EBV

EBV became the prime example of a human tumor virus that is etiologically linked to a diverse range of malignancies. EBV has been associated with a variety of lymphoid and epithelial malignancies, such as Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, T-cell lymphomas, AIDS-related lymphomas, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas of several organs including stomach, salivary glands, thymus, and lung [24]. Additionally, EBV has the unique capability to transform and immortalize resting B cells into permanently growing B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCL). As EBV is ubiquitously distributed in all human populations and more than 90% of the individuals are infected, the detection of EBV is a priori not a matter of safety. However, for quality control reasons and moreover due to the potential of EBV to transform B cells, cell banks should routinely determine the EBV infection status of cell lines. Not every cell line derived from a tumor patient is necessarily a tumor cell line as nonmalignant cells which are independent of the tumor cells may sometimes be immortalized as well. In a leukemic context, such cell lines are usually normal B-cells which become immortalized through incorporation of the EBV genome. There are several hematopoietic diseases from which it is notoriously difficult to establish cell lines, in particular the mature B-cell malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hairy cell leukemia, plasma cell leukemia (PCL), multiple myeloma, and Hodgkin lymphoma. While there are number of bona fide myeloma-, PCL-, and Hodgkin lymphoma-derived cell lines, various cell lines which are in reality EBV+ B-LCLs have been described and are still being used as model systems for these diseases. Experimental results from such misclassified cell lines might easily lead to false conclusions regarding the investigated tumor type.

Although the contamination with EBV is not detrimental to the cell culture, the effect of the contamination can be manifold. For example, the gene regulation of the cells can be influenced by transcription factors or altered methylation patterns, and central signal transduction pathways might be activated or inhibited by viral products (e.g., NF-κB, interferons) and might alter the physiology of the cells significantly.

We also investigated the presence of EBV infections in nonhematopoietic cell lines to determine whether some of the carcinoma cell lines of the above mentioned tissues might also be linked to EBV infections. In order to inhibit spread of the infections among cell cultures and for the classification of the cell lines into risk groups, it is important to know whether the infection is latent and no active viruses are produced or whether EBV particles are produced during the lytic phase of infection. In some cell lines the lytic phase of EBV infection can be induced, depending on the culture conditions. The possibility of induction of the release of active viruses was investigated by the treatment of the cells with TPA and Na-butyrate, because it is also relevant for the risk group classification of the cell lines.

The general infection status of cell lines with EBV was analyzed by PCR. This method detects linear genomes of the active EBV particles as well as EBV genomes integrated into the eukaryotic chromosomes and nonintegrated EBV episomes. The analyses revealed that 39 out of 465 primate cell lines contain sequences of the EBV genome (see Tables 2 and 3). Figure 1 shows a representative gel after performing EBV-PCR. All PCR positive human cell lines were established from B-lineage leukemia/lymphoma cells, natural killer cells, or are EBV transformed B-lymphoblastoid cells. No cell lines originating from other tissues were found to be EBV+. To demonstrate the integrity and the sensitivity of the PCR runs each sample was assayed in duplicate, one reaction without an internal control, and one reaction was spiked with the internal control DNA in a dilution that was close to the detection limit of the PCR assay (Figure 1).

Table 2.

EBV-PCR+ cell lines, BZLF1 expression detected by Western blotting, differentiation of episomal and linear EBV-DNA, EBV sequence pattern detected by Southern blotting, and episomal load determined by FISH.

| Cell line | Cell type | PCRa | BZLF1 expr.a | In situ lysing gelb | Southern blotc | FISHd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| untr. | TPA | episomal | linear | |||||

| ARH-77 | B-LCL | + | − | − | (+) | − | + | + |

| B95-8 | marmoset monkey lymphocytes | + | + | + | ++ | +++ | + | +++ |

| BD-215 | B-LCL | + | + | + | + | + | + | ++ |

| BONNA-12 | hairy cell leukemia | + | − | − | ++ | + | + | ++ (h) |

| CI-1 | B cell lymphoma | + | − | − | + | − | n.d. | + |

| COLO-720L | B-LCL | + | − | − | + | + | + | ++ |

| CRO-AP2 | B cell lymphoma | + | − | − | (+) | − | + | ++ |

| CRO-AP5 | B cell lymphoma | + | − | − | (+) | − | + | ++ |

| DAUDI | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | +++ | + | + | ++ (h) |

| DOHH-2 | B cell lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | − | + (f) |

| EB-1 | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | + | + | + | + | ++ (h) |

| EHEB | chronic B cell leukemia | + | − | − | + | (+) | + | n.d. |

| GRANTA-519 | B cell lymphoma | + | − | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| HC-1 | hairy cell leukemia | + | − | + | ++ | (+) | + | ++++ |

| IM-9 | B-LCL | + | − | + | +++ | − | + | ++++ |

| JIYOYE | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | + | ++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| JVM-13 | chronic B cell leukemia | + | − | − | ++ (2 bands) | − | + | ++++ |

| JVM-2 | chronic B cell leukemia | + | − | − | + | + | + | +++ |

| JVM-3 | chronic B cell leukemia | + | − | − | ++ | + | + | ++ |

| L-591 | B-LCL | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| LCL-HO | B-LCL | + | − | − | ++ | (+) | + | +++ |

| LCL-WEI | B-LCL | + | − | − | + | + | + | ++ |

| MEC-1 | chronic B cell leukemia | + | − | − | + | + | + | ++ (h) |

| MEC-2 | chronic B cell leukemia | + | − | − | + | − | + | ++ (h) |

| NAMALWA | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | (+) | − |

| NAMALWA.CSN/70 | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | (+) | − |

| NAMALWA.IPN/45 | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | (+) | − |

| NAMALWA.KN2 | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | (+) | − |

| NAMALWA.PNT | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | (+) | − |

| NC-NC | B-LCL | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | +++ |

| NK-92 | natural killer lymphoma | + | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| OCI-LY-19 | B cell lymphoma | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RAJI | Burkitt lymphoma | + | − | − | +++ | + | + | ++++ |

| RO | B-LCL | + | − | − | + | − | + | ++ |

| SD-1 | B-LCL | + | − | − | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| T2 | human-human somatic cell hybrid | + | − | − | ++ | + | n.d. | n.d. |

| TMM | B-LCL | + | − | − | + (2 bands) | (+) | + | +++ |

| VAL | B cell lymphoma | + | − | + | ++ (2 bands) | + | n.d. | ++ (h) |

| YT | T/natural killer cell leukemia | + | + | + | ++ | +++ | + | +++ |

B-LCL: B-lymphoblastoid cell line; expr.: expression; n.d.: not determined; untr.: untreated.

a−: negative; +: positive.

b−: negative; (+): weakly positive; +: positive; ++: strongly positive; +++: very strongly positive.

c −: no bands visible; (+): very weak signals; +: clear bands visible.

d episomal load detected by FISH: −: no episomes; +: low load; ++: load; +++: high load; ++++: very high load; (h): heterogenous distribution of the episomes among the cells; (f): only a few cells containing episomes.

Table 3.

List of cell lines tested for RT activity by ELISA, and for the presence of EBV, HBV, HCV, HIV-1, HTLV-I/-II, and SMRV.

| Cell line | Zelltyp | RT-ELISA | HCV | EBV | HBV | HIV | HTLV | SMRV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22RV1 | Prostate cancer | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 23132/87 | Gastric adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 293 | Embryonal kidney | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 293T | Embryonal kidney | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 380 | Pre B cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 42-MG-BA | Glioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 5637 | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 639-V | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| 647-V | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 697 | Pre B cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8305C | Thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8505C | Thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8-MG-BA | Glioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| A-204 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| A-427 | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| A-431 | Epidermoid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| A-498 | Kidney carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| A-549 | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| AC-1M32 | Choriocarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AC-1M46 | Choriocarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AC-1M59 | Choriocarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AC-1M81 | Choriocarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AC-1M88 | Choriocarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| ACH1P | Choricarcinoma-trophoblast hybrid | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| ALL-SIL | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AML-193 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AMO-1 | Plasmocytoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| AN3-CA | Endometrial adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| AP-1060 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| ARH-77 | Multiple myeloma | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| BC-3C | Urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| B-CPAP | Thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BD-215 | B lymphoblastoid cells | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| BE-13 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BEN | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| BEN-MEN-1 | Benign meningioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| BEWO | Choriocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| BFTC-905 | Urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BFTC-909 | Kidney transitional cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BHT-101 | Thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BHY | Oral squamous carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BL-2 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| BL-41 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| BL-70 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BLUE-1 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| BM-1604 | Prostate carcinoma (derivative of DU-145) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BONNA-12 | Hairy cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| BPH-1 | Prostate benign hyperplasia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BT-474 | Breast ductal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BT-B | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| BV-173 | Pre B cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| C-433 | Ewing's sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CA-46 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CACO-2 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CADO-ES1 | Ewing's sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAKI-1 | Kidney carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAKI-2 | Kidney carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAL-120 | Breast adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| CAL-12T | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-148 | Breast adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-27 | Tongue squamous cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-29 | Urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-33 | Tongue squamous cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-39 | Vulva carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAL-51 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAL-54 | Kidney carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAL-62 | Thyroid anaplastic carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-72 | Osteosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-78 | Chondrosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAL-85-1 | Breast adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CAPAN-1 | Pancreas adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CAPAN-2 | Pancreas adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CCRF-CEM | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CGTH-W-1 | Thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CHP-126 | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CI-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| CL-11 | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CL-14 | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| CL-34 | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CL-40 | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CMK | Acute megakaryocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CML-T1 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-206F | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-320 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-677 | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-678 | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| COLO-679 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-680N | Esophagus squamous cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-699 | Lung adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-704 | Ovary adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-720L | B lymphoblastoid cells | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-783 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-800 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-818 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-824 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COLO-849 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CPC-N | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CRO-AP2 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| CRO-AP3 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CRO-AP5 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | |

| CRO-AP6 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| CTV-1 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| CX-1 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DAN-G | Pancreas carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DAUDI | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| DB | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| DBTRG-05MG | Glioblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DEL | Malignant histiocytosis | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DERL-2 | T cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| DERL-7 | T cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| DG-75 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DK-MG | Glioblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DLD-1 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DM-3 | Sarcomatoid mesothelioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| DND-41 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| DOGKIT | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| DOGUM | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| DOHH-2 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| DU-145 | Prostate carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DU-4475 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| DV-90 | Lung adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EB-1 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| ECV-304 | Urinary bladder carcinoma (derivative of T-24) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFE-184 | Endometrium carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFM-19 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFM-192A | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFM-192B | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFM-192C | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFO-21 | Ovary cystadenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EFO-27 | Ovary adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EGI-1 | Bile duct carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EHEB | Chronic B cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| EJM | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| EM-2 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EM-3 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EN | Endometrial carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| EOL-1 | Eosinophilic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| EPLC-272H | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ESS-1 | Endometrial stromal sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| EVSA-T | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| F-36P | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| FKH-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| FU-OV-1 | Ovarian cancer | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| GAMG | Glioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| GDM-1 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| GF-D8 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| GIRARDI HEART C2 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| GIRARDI HEART C7 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| GMS-10 | Glioblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| GOS-3 | Astrocytoma/oligodendroglioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| GRANTA-519 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| GUMBUS | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| H-1184 | Lung small cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| H-1339 | Lung small cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| H-1963 | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| H-209 | Lung small cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| H-2171 | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HAL-01 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HC-1 | Hairy cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| HCC-1143 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-15 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-1599 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-1937 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-33 | Lung small cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-366 | Lung squamous adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-44 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-78 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCC-827 | Non-small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCEC-12 | Cornea endothelium | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCEC-B4G12 | Cornea endothelium | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCEC-H9C1 | Cornea endothelium | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HCT-116 | Colon carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| HCT-15 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HDLM-2 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HD-MY-Z | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HDQ-P1 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HEL | Erythroleukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HELA | Cervix carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HELA-S3 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HEP-3B | Hepatocellular carcinoma | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| HEP-G2 | Hepatocellular carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HL-60 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HMC-1 | Mast cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HN | Oral squamous carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HNT-34 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HPB-ALL | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| HSB-2 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HT | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HT-1080 | Fibrosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HT-1376 | Bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HT-29 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| HTC-C3 | Thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HUP-T3 | Pancreas carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| HUP-T4 | Pancreas carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| IGR-1 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| IGR-37 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| IGR-39 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| IM-9 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| IMR-32 | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| IPC-298 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| JAR | Choriocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JEG-3 | Choriocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JEKO-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JIMT-1 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JIYOYE | B cell lymphoma | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| JJN-3 | Plasma cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JK-1 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| JL-1 | Epitheloid mesothelioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JMSU-1 | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JOSK-I | Histiocytic lymphoma (derivative of U-937) | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JOSK-M | Histiocytic lymphoma (derivative of U-937) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| JURKAT | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| JURL-MK1 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JURL-MK2 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| JVM-13 | Chronic B cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| JVM-2 | Chronic B cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| JVM-3 | Chronic B cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| K-562 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KARPAS-1106P | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KARPAS-231 | B cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KARPAS-299 | T cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KARPAS-422 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KARPAS-45 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KARPAS-620 | Plasma cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KASUMI-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KASUMI-2 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KB | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KB-3-1 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KB-V1 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KCI-MOH1 | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KCL-22 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| KE-37 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KELLY | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KG-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KG-1a | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KM-H2 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KMOE-2 | Acute erythremia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KMS-12-BM | Myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KMS-12-PE | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KOPN-8 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KPL-1 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KU-19-19 | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KU-812 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in myeloid blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYO-1 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| KYSE-140 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-150 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-180 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-270 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-30 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-410 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-450 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-510 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-520 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| KYSE-70 | Esophageal carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| L-1236 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| L-363 | Plasma cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| L-428 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| L-540 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| L-591 | B lymphoblastoid cells | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| L-82 | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| LAMA-84 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LAMA-87 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LCLC-103H | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LCLC-97TM1 | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LCL-HO | B lymphoblastoid cells | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| LCL-WEI | B lymphoblastoid cells | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| LN-405 | Astrocytoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LNCAP | Prostata carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LOUCY | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LOU-NH91 | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LOVO | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| LP-1 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| LXF-289 | Lung adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| M-07e | Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MB-1 | Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MC-116 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MCF-7 | Breast adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MDA-MB-453 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ME-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MEC-1 | Chronik B cell leukemia | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| MEC-2 | Chronic B cell leukemia | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| MEG-01 | chronic myeloid leukemia in megakaryocytic blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MEL-HO | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MEL-JUSO | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MFE-280 | Endometrium carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MFE-296 | Endometrium carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MFE-319 | Endometrium carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MFM-223 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MHH-CALL-2 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MHH-CALL-3 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MHH-CALL-4 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MHH-ES-1 | Ewing's osteosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MHH-NB-11 | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MHH-PREB-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MKN-45 | Gastric carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| ML-1 | Follicular thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| ML-2 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MN-60 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOLM-13 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MOLM-16 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MOLM-20 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MOLM-6 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| MOLP-2 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MOLP-8 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MOLT-13 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOLT-14 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOLT-16 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOLT-17 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOLT-3 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOLT-4 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MONO-MAC-1 | Acute monocytic Leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MONO-MAC-6 | Acute monocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MOTN-1 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MSTO-211H | Lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MT-3 | Breast carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MUTZ-2 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MUTZ-3 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MUTZ-5 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| MV4-11 | Acute monocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| NALM-1 | Chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| NALM-19 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| NALM-6 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| NAMALWA | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| NAMALWA.CSN/70 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| NAMALWA.IPN/45 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| NAMALWA.KN2 | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| NAMALWA.PNT | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| NB-4 | Acute promyelocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| NCI-H510A | Small cell extra-pulmonary carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| NCI-H82 | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| NCI-H929 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| NC-NC | B-lymphoblastoid cells | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| NK-92 | Natural killer cell lymphoma | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| NOMO-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| NTERA-2 | human embryonal carcinoma (teratocarcinoma) | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| NU-DHL-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| NU-DUL-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| OCI-AML2 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| OCI-AML3 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| OCI-AML5 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| OCI-LY-19 | B cell lymphoma | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| OCI-M1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| OCI-M2 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| ONCO-DG-1 | Papillary thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| OPM-2 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| P12-ICHIKAWA | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PA-TU-8902 | Pancreas adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PA-TU-8988S | Pancreas adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PA-TU-8988T | Pancreas adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PC-3 | Prostate carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| PEER | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PF-382 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| PL-21 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| PLB-985 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RAJI | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| RAMOS | Burkitt lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RCH-ACV | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RC-K8 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RD-ES | Ewing's osteosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| REC-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| REH | Pre B cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RH-1 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RH-18 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RH-30 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RH-41 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RI-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RL | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RO | B lymphoblastoid cell line | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| ROS-50 | B cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| RPMI-2650 | Nasal septum squamous carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RPMI-7951 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RPMI-8226 | Multiple myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RPMI-8402 | T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RS4;11 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RS-5 | Sacromatoid mesothelioma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| RT-112 | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RT-4 | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| RVH-421 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| S-117 | Thyroid sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SAOS-2 | Osteogenic carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SBC-2 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SBC-7 | Cervix carcinoma (subclone of HELA) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SC-1 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SCC-25 | Squamous cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| SCC-4 | Squamous cell carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| SCLC-21H | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SCLC-22H | Small cell lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SD-1 | B lymphoblastoid cells | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| SEM | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SET-2 | Essential thromobocythemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SH-2 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SHI-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SH-SY5Y | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SIG-M5 | Acute monocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SIMA | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SISO | Cervix carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SK-ES-1 | Ewing's sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SK-HEP-1 | Liver adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SKM-1 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SK-MEL-1 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SK-MEL-3 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SK-MEL-30 | Melanoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SK-MES-1 | Squamous lung carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SK-MM-2 | Multiple Myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SK-N-BE(2) | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SK-N-MC | Neuroblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SKW-3 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SNB-19 | Glioblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SPI-801 | Chronic myeloid leukemia (K-562 subclone) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SPI-802 | Chronic myeloid leukemia (K-562 subclone) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SR-786 | Anaplastic large T cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SU-DHL-1 | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SU-DHL-10 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SU-DHL-16 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SU-DHL-4 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SU-DHL-5 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SU-DHL-6 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SU-DHL-8 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SUP-B15 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SUP-HD1 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SUP-M2 | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SUP-T1 | T cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SUP-T11 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| SW-1710 | Urinary bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SW-403 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SW-480 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| SW-948 | Colon adenocarcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| T2 | Human-human somatic cell hybrid | − | + | − | − | − | ||

| T-24 | Bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TALL-1 | T cell leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| TANOUE | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TC-71 | Ewing's sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| TCC-SUP | Bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TE-671 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TF-1 | Erythroleukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TFK-1 | Bile duct carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| THP-1 | Acute monocytic leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| TMM | Chronic myeloid leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| TOM-1 | B cell precursor leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| TT2609-C02 | Follicular thyroid carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | ||

| U-138-MG | Glioblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| U-2197 | Malignant fibrous histiosarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| U-266 | Myeloma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| U-2932 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| U-2940 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| U-2973 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| U-698-M | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| U-937 | Hystiocytic lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| U-H01 | Hodgkin lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| ULA | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| UT-7 | Acute myeloid leukemia | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VA-ES-BJ | Epithelioid sarcoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VAL | B cell l | − | + | − | − | − | − | |

| VM-CUB1 | Bladder carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| WERI-RB-1 | Retinoblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| WSU-DLCL2 | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| WSU-FSCCL | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| WSU-NHL | B cell lymphoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Y-79 | Retinoblastoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| YAPC | Pancreatic carcinoma | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| YT | T cell/natural killer cell leukemia | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| B95-8* | Lymphocytes | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| COS-1* | Kidney | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| COS-7* | Kidney | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| VERO-B4* | Kidney | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

*: Monkey cell lines; −: negative; + (bold): positive.

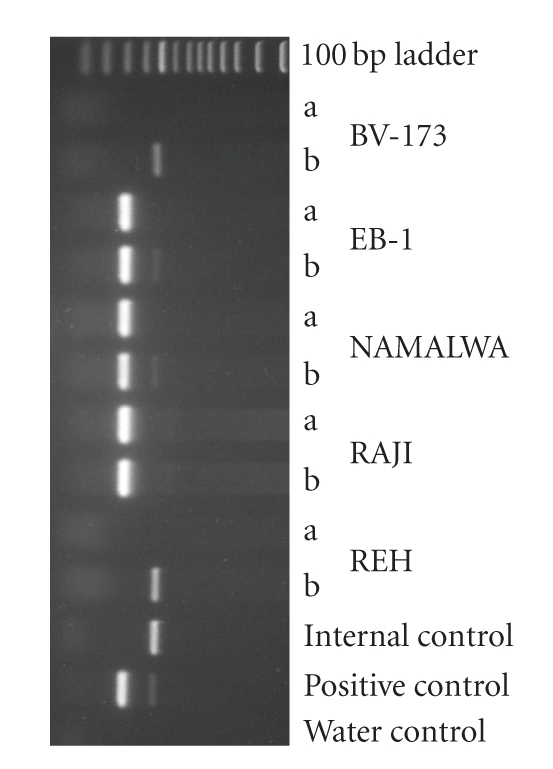

Figure 1.

PCR analysis of EBV status in cell lines. Shown is an ethidium bromide-stained gel containing the reaction products following PCR amplification with the primers F-EBV and R-EBV (see Table 1). Products of 265 bp were obtained. Shown are various examples of EBV-negative and EBV-positive cell lines. Two paired PCR reactions were performed: one PCR reaction contained an aliquot of the sample only (a) and the second reaction contained the sample under study plus the control DNA as internal standard, which results in an amplified product size of 445 bp (b). The cell cultures EB-1, NAMALWA, and RAJI are EBV-positive; the cell cultures BV-173 and REH, both B-cell precursor leukemia cell lines, are EBV-negative.

A number of cell lines were examined for EBV infection by the originators of the cell lines or later on by other investigators. In the majority of cases the EBV status of the cell lines was determined immunologically by the detection of EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA), early antigen (EA), and/or viral capsid antigen (VCA). Concordance of our PCR results with data for protein expression given in the literature was found in nine cell lines (ARH-77, BONNA-1, HC-1, JIYOYE, L-591, MEC-1, MEC-2, RAJI, and YT) [9, 25, 26]. The DOHH-2 cell line was originally described as EBV negative but was later on found to be EBV positive in EBNA immunofluorescence staining and PCR [27, 28]. In three cell lines (CRO-AP2, CRO-AP5, and HC-1) EBV sequences were demonstrated by Southern blotting [29–31] and four cell lines were described to be established by immortalization with EBV particles from supernatant of the B95-8 cell line (EHEB, JVM-13, JVM-2, and JVM-3) [32, 33]. The monkey cell line B95-8 is known to produce infectious EBV particles [34]. In contrast to our PCR results, the cell lines CI-1, NK-92, and TMM were specified as EBV negative as examined by EBNA and PCR assays [35–37]. Our PCR results were verified by FISH, in situ lysing gel analysis, Southern and Western blotting as described below and showed in at least two additional assays that all those cell lines are clearly EBV-positive (see Table 2).

The CI-1, DOHH-2, and TMM cell lines were positive in our PCR assay but showed weak or few signals in in situ lysing gel analysis and FISH (see below). This indicates that the EBV load of the cells is very low and that the expression of EBNA protein in these three cell lines was below the detection limit of the immunological assays. Thus, PCR is a convenient and reliable assay to detect EBV infections in cell cultures, provided that the appropriate control reactions including internal DNA controls are performed to avoid false positive and false negative results.

The activation of the lytic phase of the virus is usually closely connected with the production of infectious virus particles in the cells. The permissivity of a cell line relating to EBV is important to determine legally the risk group of the cell line as only cell cultures producing active viruses should represent an elevated risk. To identify the lytic phase of the EBV infections, we analyzed the expression of the ZEBRA protein (Bam HI Z Epstein-Barr replication activator) [38] by Western blotting applying an anti-ZEBRA monoclonal antibody. ZEBRA is the product of the BZLF1 gene and is a transcriptional activator that mediates a genetic switch between the latent and lytic states of EBV. ZEBRA binds to the promoters of genes involved in lytic DNA replication activating their transcription [39]. Thus, phorbol esters and Na-butyrate are among the most reproducible and most broadly applicable inducers of the lytic cycle of EBV [8]. However, not all latently infected lymphoblast cell lines can be induced by TPA and only a minority of the cells within a culture is inducible at all. In some human B-LCL about 10% of the cells can be induced to permit lytic virus replication, whereas in a few others 20%–50% induced cells can be found [8]. Marmoset lymphoblasts seem to be more inducible, for example, the B95-8 cell line [40]. For this reason we used the B95-8 cell line as positive control to determine the efficiency of the induction with TPA/Na-butyrate.

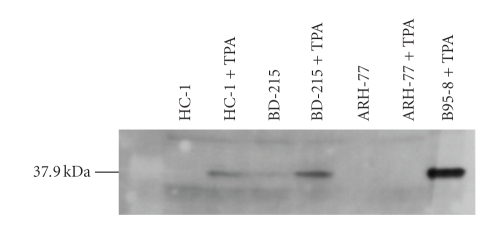

All EBV PCR+ cell lines were incubated with and without 10−7 M TPA for 3 days and analyzed for ZEBRA expression. As shown in Table 2, five unstimulated cell lines exhibited a ZEBRA specific band of approximately 40 kDa (B95-8, BD-215, L-591, NC-NC, and YT). The expression of the protein was weak in all five cell lines but increased after TPA/Na-butyrate stimulation. B95-8 and BD-215 increased strongly, whereas L-591 and YT increased only moderately. Six additional cell lines which showed no expression in the absence of TPA/Na-butyrate produced the ZEBRA protein in various amounts after induction of the lytic phase with TPA (EB-1, GRANTA-519, HC-1, IM-9, JIYOYE, and VAL). All other cell lines tested (n = 28) did not express the BZLF1 gene product even after stimulation with TPA/Na-butyrate. Figure 2 shows a representative Western blot with positive and negative cell lines. Lieberman et al. [41] showed that the ZEBRA protein is induced by TPA in RAJI cells. This was not confirmed in our screening for ZEBRA expression. RAJI is a nonproducer cell line with at least two deletions in the EBV genome and is defective for EBV DNA replication and late gene expression [8]. On the other hand, Di Francesco et al. [42] showed a weak induction of ZEBRA in Western blots after treatment with TPA in combination with n-butyrate, whereas further addition of cocain caused a high increase in ZEBRA expression. These contradictory findings can be explained by different cell sources or cell passage histories. However, importantly all studies demonstrated that ZEBRA was not expressed during normal cell culture, and thus, a production of viruses is very unlikely at nonstimulating conditions.

Figure 2.

Detection of ZEBRA protein in EBV+ cell lines. Western blot analysis with antibodies raised against ZEBRA shows that ZEBRA can be induced in the cell line HC-1 and that the cell line BD-215 can be stimulated to increase the expression of the immediate early protein. Expression in ARH-77 could not be induced by TPA during 72 hours. TPA-stimulated B95-8 was used as control for the expression of ZEBRA.

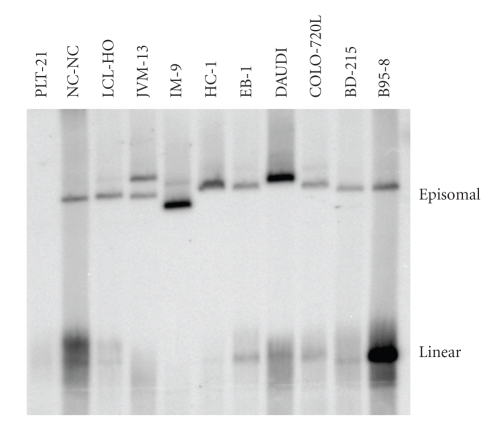

The EBV genome can be present in the host cells as covalently closed circles (episomes), as linear DNA of active viruses, or integrated into the host genome. The episomes are indicative for the latent infection status [8]. The EBV infected cells can harbor 1–10 episomes in low load cells or up to several hundred episomes in high load cells. EBV producer cell lines contain also linear double stranded DNA which is packaged into the virions. EBV genome integration was described only for a small number of cell lines. For example, the NAMALWA cell line and its subclones are described to contain an integrated EBV genome [43] and no episomes, whereas the RAJI cell line was reported to contain both, chromosomally integrated EBV genomes as well as episomes [44]. To distinguish between the linear DNA of active viruses, episomal DNA of EBV-infected cell cultures, and solely integrated EBV genomes, we performed a variation of a Southern blot analysis as described by Gardella et al. [14].

The autoradiograms showed the episomal DNA as clear-cut bands whereas the linear DNA usually formed distinct bands within a smear of DNA (Figure 3). The episomal as well as the linear DNA of the cell lines examined showed different migrations indicating different EBV clones. Except for the NAWALWA cell line and its subclones, DOHH-2, and OCI-LY19, all EBV PCR positive cell lines showed at least one band of episomal EBV genomes (Table 2). As no denaturing conditions were applied in the in situ lysing gels, different sequences of the EBV strains can result in different conformations and mobilities of the episomes. The cell lines COLO-720L, IM-9, JVM-13, LCL-HO, TMM, and VAL displayed two episomal DNA bands. The intensities of the episomal bands were almost identical only in the cell line JVM-13. The existence of two EBV clones in one cell line can be explained by three assumptions: (i) two different EBV clones simultaneously infected the cell which led to the establishment of the cell line, (ii) the cell line was established from two or more different cells of the patient harboring different EBV clones (oligoclonality), or (iii) single and duplicated episomes are present in the nuclei of the cell lines.

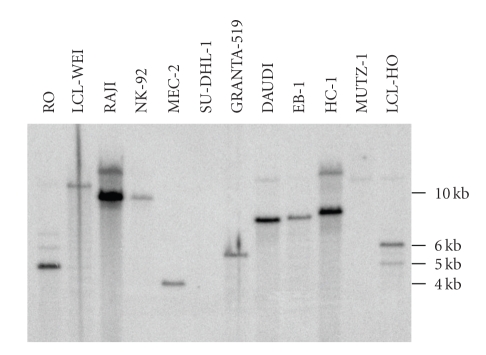

Figure 3.

Detection of circular and linear EBV DNA in cell lines by in situ lysing gel analysis. 106 cells were resuspended in a loading buffer containing RNase A and loaded into a well of a 0.8% agarose-TBE lysing gel containing SDS and proteinase K. After electrophoresis the separated DNA was blotted onto nylon filters and the DNA was hybridized with 32P labeled EBV cosmid cM-SalI-A. The upper bands on the autoradiograph constitute the episomal DNA, whereas the lower bands constitute the linear EBV-DNA which is packed into the active viruses during virus formation. EBV genoms integrated into the chromosomes of the cells do not enter the gel. Controls include B95-8 as EBV-positive and PLT-21 as EBV-negative cell lines. Episomal EBV DNA can be detected in all EBV positive cell lines. The amount of linear EBV-DNA is highly diverse or not present (IM-9, JVM-13) and does not correlate with the amount of episomal DNA.

The NK-92 and TMM cell lines were described to be EBV negative according to EBNA detection assay and PCR, respectively [35, 37]. Both cell lines showed EBV specific episomal DNA in the in situ lysing gels. This confirmed the results of the PCR assay as discussed above. Concerning the NAMALWA cell lines, no episomal DNA bands were expected, because the EBV DNA was described to be integrated into the eukaryotic genome [45]. Since no linear DNA was detected, the integrated genome is not transcribed in those cell lines. DOHH-2 and OCI-LY-19 might also only contain integrated EBV genomes, but fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) indicates that the number of EBV episomes in a cell culture is too low to be detected by in situ lysing gels (see below).

The intensities of the episomal bands in the in situ lysing gels were highly variable among the cell lines but were constant for a given cell line, indicating that the EBV loads are different in the cell lines examined. The highest episomal loads were found in the cell lines DAUDI, IM-9, L-591, RAJI, and SD-1. Of these, only the L-591 cell line expressed BZLF1 constitutively and IM-9 expressed the protein after stimulation with TPA and Na-butyrate. The other BZLF1 expressing cell lines displayed a lower number of episomes. This indicates that the lytic cycle induction is completely indepentent from the number of episomes present in the nuclei. High episomal loads were described for the cell line DAUDI and RAJI, which carry 100–200 and 50–60 viral copies per cell, respectively [23, 46]. Based on the intensities of the EBV-specific bands in the autoradiograms of the in situ lysing gel assays, the numbers of episomes in IM-9 and SD-1 were comparable to those of DAUDI or RAJI, respectively. All other cell lines were low load cell lines with 1–10 EBV copies per cell compared to the high load cell lines mentioned above (Figure 3).

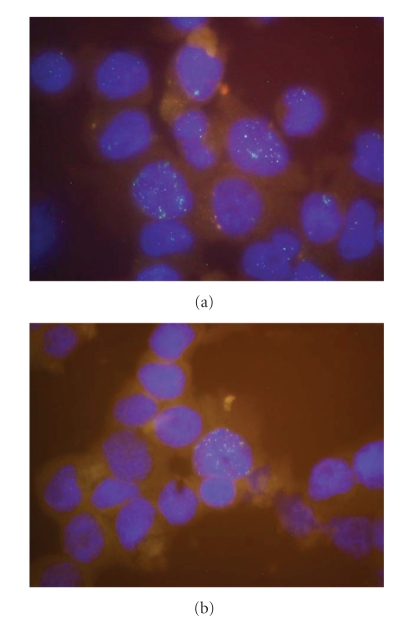

In order to obtain more quantitative data on the EBV load of the EBV+ cell lines, we performed single cell analyses by interphase FISH. The analysis showed that the viral load of the nonproducing cells within a culture was heterogeneous. Some cells had high EBV loads, whereas other cells of the same cell culture showed low or even no viral load. For example, the cell line DOHH-2 contains only a few cells with several EBV episomes, whereas in most of the cells EBV DNA was completely absent (Figure 4(b)). Any cross-contamination of the cell line was excluded by DNA typing (data not shown). The heterogeneity of EBV load within a cell culture population and the finding that only a small fraction of cells can be stimulated to enter the lytic phase implies that specific cellular factors regulate the propagation of episomes in the nuclei and the permissivity of the cells related to EBV. Phosphorylation or methylation of EBV specific proteins or epigenetic events like DNA methylation or histone deacetylation might contribute to the cell specific regulation [39].

Figure 4.

Interphase FISH assay for the demonstration of EBV in cell lines. Hybridization was performed with EBV cosmid cM-SalI-A labeled with Spectrum Green by nick-translation. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. (a) Nuclei of cell line BONNA-12 contains heterogeneous numbers of EBV copies. (b) Cell line DOHH-2 displays only few cells contaminated with EBV.

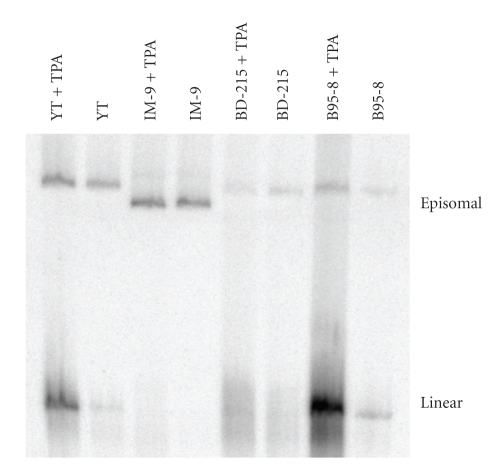

Linear EBV DNA was detected in a number of cell lines (Table 2). The expression of linear EBV genome DNA did not correspond to the expression of BZLF1 protein. Although all BZLF1 positive cell lines produced high levels of linear EBV DNA, many more BZLF1 negative cell lines also expressed significant levels of linear EBV genomes. This indicates that the lytic status of the EBV infection is not essential for the production of linear EBV genomes. The intensities of the linear EBV DNA bands did not correlate to the intensities of the episomes. For example, the cell line IM-9 displayed a very strong episomal DNA signal, whereas no linear DNA was detectable in untreated cells and very low amounts were seen in TPA/Na-butyrate treated cells (Figure 5). On the other hand, cell line YT showed a strong band for linear DNA, but a weak band for the episomal DNA. The number of episomes per cell was not affected by the stimulation with TPA/Na-butyrate, whereas the amount of linear DNA increased with the addition of TPA in those cell lines which can be stimulated with the phorbol ester.

Figure 5.

Detection of circular and linear EBV DNA in untreated and TPA-treated cell lines by in situ lysing gel analysis. Cells were stimulated for 72 hours with 10−7 M TPA and 0.3 M Na-butyrate. All conditions were as described in the legend for Figure 3. The cell lines B95-8 and YT can be efficiently stimulated to produce high amounts of linear EBV genomes, whereas BD-215 cannot be triggered to produce more linear DNA and IM-9 is not induced to produce linear DNA by TPA/Na-butyrate.

Cross-contamination is a serious problem in cell culture and causes mycoplasma infection and cell line cross-contamination. To find out whether a transfer of EBV from one cell culture to another can be demonstrated, we investigated the clonality of the EBV genomes. We performed Southern blot analysis with genomic DNA of the EBV-PCR positive cell lines digested with the restriction enzyme XhoI. Applying EBV cosmids covering almost the whole EBV genome [15] each cell line displayed a unique EBV genotype. The most striking differences occurred in the lengths of the terminal repeat (TR) regions which reflect the numbers of repetitive exons. The other parts of the genome covered by the cosmids (ca. 83% of the B95-8 EBV sequence) showed also a high variability. Several different patterns can be identified per cosmid probe and the combination of several cosmid probes revealed a high number of different genotypes (Figure 6). Even the cell lines which were described to be established with EBV particles of the B95-8 cell line displayed differences in the lenght of the TR regions of the EBV genotypes. The JVM cell lines were all established using EBV and TPA [32]. Nevertheless, the cell lines display different patterns concerning the TR region and a few additional bands within the EBV genome. The EHEB cell line was also described to be transformed by B95-8 EBV viruses [9]. The EHEB cell line displays distinct bands in the XhoI-digested EBV DNA different from those found in the JVM cell lines. Nevertheless, the bands of the B95-8 EBV-transformed cell lines detected in the Southern blots are all more or less prominently represented within the pattern of the B95-8 cell line. From these results, we conclude that the B95-8 cell line harbors different genotypes of EBV with the ability to transform other cells.

Figure 6.

Southern blot analysis of different cell lines. Fifteen μg genomic DNA of the cell lines were digested with XhoI and the restriction fragments were separated on an agarose gel. The DNA was blotted onto nylon filters and the blot was hybridized to a ca. 900 bp 32P-labeled PCR product spanning the 5′-region of EBV (LMP fragment 1). A rehybridization of the same blot with a probe for the 3′-region of the linear EBV genome after stripping revealed the same bands, indicating that circular EBV DNA is detected.

Taken together, the various patterns of digested EBV indicate that the infections with EB viruses originated from the patient or from the transforming viruses, but not from dissemination during cell culturing. Although mycoplasma and cross contaminants are mainly introduced into cell cultures by inadequate cell culture techniques, this does not seem to be the case with regard to the distribution of EBV in cell cultures. The low number of unintended intercell line contamination by EBV might be based on the low number of cell lines which produce actively EBV. Additionally, only a limited number of cell lines are susceptible to the infection with EBV at all.

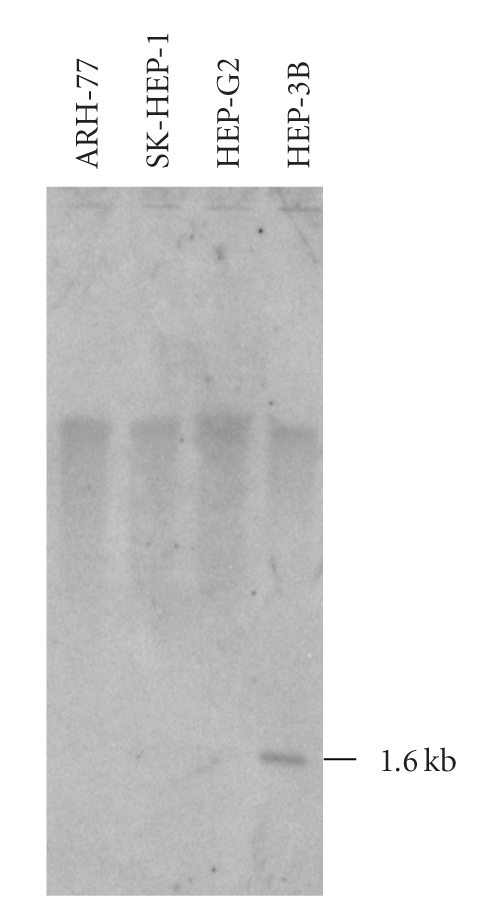

3.2. Detection of HBV

HBV particles contain a circular, partially double-stranded DNA of 3.2 kb. HBV can be grown in primary cell cultures of normal adult or fetal human hepatocytes, but propagation was not yet shown in untreated continuous cell lines. Production of HBV particles can be achieved to date only by transfection of hepatocyte cell lines with plasmids containing HBV genomes [47]. In cell lines, the HBV genome is integrated into the eukaryotic chromosomes with variable copy numbers as shown for several cell lines, for example, HCCM, HEP-3B, HUH-1, HUH-4, and PLC/PRF/5 [48]. Except for HCCM, all these cell lines express the hepatitis B surface antigen HBsAg.

The HBV PCR assay used here amplified conserved sequences of the core region of HBV and was evaluated using HBV reference plasma No 1 (subtype ad) and No 2 (subtype ay) which were established in cooperation with the European Study Group on Viral Hepatitis (EUROHEP). In order to determine the detection limit, we performed a dilution series of the HBV particles in conditioned cell culture supernatant of an HBV negative cell line. Subsequently, the HBV particles were recollected by ultracentrifugation, DNA was extracted, and the PCR reaction was performed as described in the methods section. The sensitivity was determined as ca. 50 particles per PCR reaction. This corresponds to ca. 250 HBV particles per mL cell culture supernatant (data not shown).