Abstract

The catalytic subunit of protein kinase A is involved with a number of signal transduction pathways and has been used as a benchmark to study the structural biology and biochemistry for the entire kinase family of enzymes. Here, we report the backbone assignment of the intact 41 kDa catalytic subunit bound to AMP-PNP.

Keywords: Protein kinase A, NMR, protein backbone resonance assignments, dual amino acid selective labeling, CCLS-HSQC

Biological context

Protein kinase mediated phosphorylation is a key process for cellular signal transduction. Approximately 30% of all proteins in the human genome undergo reversible phosphorylation (Cohen 2001). As a consequence, abnormal protein kinase activity has been recognized as one of the main causes for diseases such as cancer, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and some types of dilated cardiomyopathy. In fact, drugs such as rapamycin and flavopiridol have been shown to target protein kinase activity (Cohen 2001).

Since Protein Kinase A (EC: 2.7.11.11) is the most conserved protein kinase, it has served as the prototype to study the kinase family (Johnson et al. 2001). The catalytic subunit of PKA (PKA-C) shares the domain organization of all of the kinase catalytic domains, with a bean-like arrangement of two lobes to form an active site cleft. The small lobe is primarily associated with binding and positioning the nucleotide ligand, while the large lobe binds a protein substrate and provides a docking surface for the regulatory subunits (Johnson et al 2001). Highly conserved motifs within PKA-C include: the C-helix (located in the small lobe) and a series of dynamic loops responsible for catalysis and positioned at the fringe between the small and the large lobe (the peptide positioning loop, the activation loop, the Mg2+-positioning loop, Glycine-rich loop, and DFG loop). Mutations within these motifs have been shown to cause large scale changes in kinase activity and/or proper folding of the enzyme (Johnson et al. 2001).

While a wealth of structural data is available for PKA-C from x-ray crystallography (Johnson et al. 2001), little is known about the atomic level detail of its dynamics or interaction with membrane proteins. Due to their dynamic nature, intact protein kinase domains are notoriously resistant to NMR analysis and a handful of NMR studies are now available. Our initial NMR investigation on PKA-C demonstrated the existence of a positive allosteric cooperativity driven in part by a dynamic sampling of conformational states. In order to fully analyze the dynamic transitions of PKA-C by NMR, we have carried out the backbone resonance assignment of the enzyme bound to AMP-PNP (5′-adenylyl-β,γ-imidodiphosphate) using 2H, 13C, and 15N labeled protein and extensive selective labeling. To date, we reached ~80% of the total resonances, leaving only regions in helices D and E (both located at the stable core of the enzyme) unassigned. Taken together with the limited NMR characterizations of the enzymatic family of kinases, such as Abl kinase (Vajpai et al. 2008), this represents a step towards studying the dynamical features and molecular interactions by NMR.

Methods and experiments

PKA-C expression and purification was carried out based on the protocols established by Taylor and co-workers (Yonemoto et al. 1991). Based on our screening of optimal 2H2O concentration for expression, M9 minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl and D-glucose-13C6-2H7 in 80% 2H2O was used to produce perdeuterated enzyme for triple resonance experiments. Deuterium incorporation was greater than 95% based on mass spectrometry (see Supplementary Materials Figure S1 and Table S1). Extensive selective amino acid labeling was utilized for the identification of 15 residue types in 1H/15N TROSY-HSQC spectra: Ala, Val, Leu, Ile, Lys, Arg, Thr, Ser, Gly, His, Phe, Tyr, Trp, Met, and Asn. Introduction of specific 1-13C and 15N labeled amino acids for dual amino acid labeling allowed the assignment of the following unique 13C’-15N linked dipeptides in the primary sequences: LL (3 occurrences), LI (3 occurrences), FG (2 occurrences), and GF (1 occurrence). Cells were grown at 30 °C until reaching an OD of 1.2, at which the temperature was reduced to 24 °C and protein overexpression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside). Typically, expression was allowed to proceed for 12 hours (deuterated media) or 5 hours (non-deuterated media). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7,000 g for 20 minutes at 4 °C and flash frozen in N2 (l) prior to purification. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer containing 100 mM MES (pH 6.5), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.15 mg/ml lysozyme; and lysed on ice by sonication for 10 minutes. Cell debris were cleared by centrifugation at 75,000 g and PKA-C was isolated by binding the supernatant batch-wise to P11 phosphocellulose resin and eluting over a gradient of 0-250 mM K2HPO4 dissolved in lysis buffer. Fractions containing purified enzyme were pooled and dialyzed against 20 mM K2HPO4 (pH 6.5), 25 mM KCl, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (buffer A). Since recombinant PKA-C is found to have three phosphoisoforms (containing either 2, 3, or 4 phosphoserine or phosphothreonine residues), isoforms were separated by cation exchange chromatography on a Mono-S column using a gradient of 0-30% KCl dissolved in buffer A. All NMR experiments were performed on the isoform containing three phosphates.

Triple resonance NMR experiments were performed on a sample containing 0.28 mM PKA-C, while all other samples contained 0.5-1.0 mM total enzyme. Samples were dissolved in 180 mM KCl, 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 1 mM NaN3, 20 mM DTT, 15 mM MgCl2, 5% 2H2O, and 15 mM of the non-hydrolyzable nucleotide analogue, AMP-PNP. All experiments were performed at 300 K on Varian Inova 800 or 600 MHz NMR spectrometers equipped with triple resonance cryogenic probes with z-axis pulse field gradients. Backbone assignments were based on TROSY versions of HSQC, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCAB, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, a 1H/1H NOESY-HSQC (τmix = 100 ms) (Grzesiek and Bax 1992) as well as a non-TROSY version of a nitrogen-edited HSQC-NOESY-HSQC (τmix = 100 ms) (Grzesiek et al. 1995). Due to the detection of broad resonances from real-time 13C evolution, isotope effects of 13C resonances from attached 1H and 2H were not observed. Unique resonances resulting from dual selective amino acid labeling were observed by using either a 2D HNCO or a CCLS-HSQC sequence (Tonelli et al. 2007). All data were processed using the software NMRPipe (Delaglio et al. 1995) and visualized with SPARKY (Goddard and Kneller 2006).

Extent of assignments and data deposition

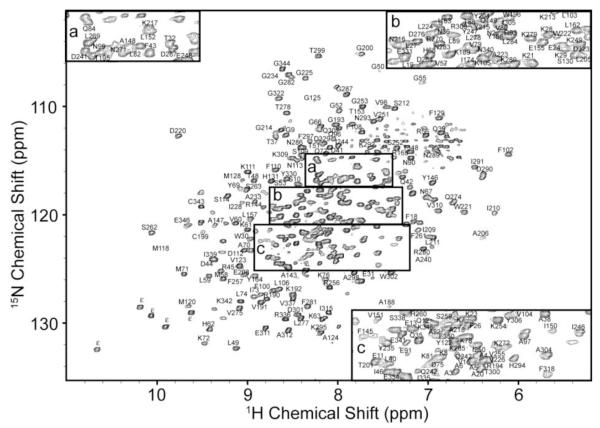

A 1H/15N-TROSY-HSQC of perdeuterated PKA-C is shown in Figure 1. Backbone resonance assignments have been achieved for 80% of the non-proline amide groups, ~80% of the Cα and C’ resonances and 47% of the Cβ resonances. Despite a handful of missing assignments which are located in two long helices in the stable core of the enzyme (Johnson et al. 2001), all of the highly conserved regions have been assigned and include the C-helix, peptide positioning, activation, Mg2+-positioning, glycine-rich, and DFG–loops. These resonance assignments compare well with the previous partial assignment (~55%) of the apo-enzyme (Langer et al. 2004). It should be noted that higher signal-to-noise was observed when PKA-C was bound to AMP-PNP relative to the apo form of the enzyme, although the glycine and two phenylalanine resonances in the 184DFGF187 sequence were broadened beyond detection. These were assigned using the apo enzyme with a CCLS-HSQC experiment as has been noted elsewhere (Tonelli et al. 2007). The remaining missing assignments are largely located in two long helices (helices D and E), and are due to missing Cβ resonances in the HNCACB spectra and severe overlap for Cα or 15Nα resonances. A chemical shift index of assigned Cα resonances is provided in Supplementary Materials as Figure S2.

Fig. 1.

1H/15N-TROSY-HSQC spectrum of perdeuterated PKA-C complexed to AMP-PNP in 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 180 mM KCl, 20 mM DTT, and 1 mM DTT collected at 300 K on a Varian Inova 800 MHz NMR spectrometer. Assignment information is placed next to peaks and subpanels a, b, and c are provided for clarity. Indolic nitrogen resonances of tryptophan are denoted with the symbol ε.

The chemical shift values for 1H, 13C, and 15N resonances of PKA-C have been deposited at the BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) under accession number 15985.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants GM64742 and HL080081 (G.V.), and GM08700 (L.R.M.). The University of Minnesota NMR facility is supported by NSF funding BIR-961477 and the University of Minnesota Medical Foundation. NMRFAM is supported by NIH grants P41RR02301, P41GM66326, RR02781, and RR08438, along with NSF grants DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, and BIR-9214394.

Contributor Information

Larry R. Masterson, Departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA vegli001@umn.edu

Lei Shi, Departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA vegli001@umn.edu.

Marco Tonelli, National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, Department of Biochemistry University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA tonelli@nmrfam.wisc.edu.

Alessandro Mascioni, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Andover, MA 01810, USA AMascioni@wyeth.co m.

Michael M. Mueller, Departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA vegli001@umn.edu

Gianluigi Veglia, Departments of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, and Biophysics University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA vegli001@u mn.edu.

References

- Cohen P. The role of protein phosphorylation in human health and disease. Eur.J.Biochem. 2001;268:5001–5010. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3.113. 2006.

- Grzesiek S, Bax A. Improved 3D triple-resonance NMR techniques applied to a 31 kDa protein. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1992;96:432–440. 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Grzesiek S, Wingfield P, Stahl S, Kaufman J, Bax A. Four-Dimensional 15N-Separated NOESY of Slowly Tumbling Perdeuterated 15N-Enriched Proteins. Application to HIV-1 Nef. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9594–9595. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DA, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem.Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer T, Vogtherr M, Elshorst B, Betz M, Schieborr U, Saxena K, Schwalbe H. NMR backbone assignment of a protein kinase catalytic domain by a combination of several approaches: application to the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chembiochem. 2004;5:1508–1516. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli M, Masterson LR, Hallenga K, Veglia G, Markley JL. Carbonyl carbon label selective (CCLS) 1H-15N HSQC experiment for improved detection of backbone 13C-15N cross peaks in larger proteins. J.Biomol.NMR. 2007;39:177–185. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9185-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajpai N, Strauss A, Fendrich G, Cowan-Jacob SW, Manley PW, Grzesiek S, Jahnke Wolfgang. Solution Conformations and Dynamics of ABL Kinase-Inhibitor Complexes Determined by NMR Substantiate the Different Binding Modes of Imatinib/Nilotinib and Dasatinib. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18292–18302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonemoto WM, McGlone ML, Slice LW, Taylor SS. Prokaryotic expression of catalytic subunit of adenosine cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:581–596. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00173-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.