Abstract

p66Shc is an adapter protein that is induced by hypertrophic stimuli and has been implicated as a major regulator of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cardiovascular oxidative stress responses. This study implicates p66Shc in an α1-adrenergtic receptor (α1-AR) pathway that requires the cooperative effects of protein kinase (PK)Cε and PKCδ and leads to AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes. α1-ARs promote p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation via a ROS-dependent mechanism that is localized to caveolae and requires epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and PKCε activity. α1-ARs also increase p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation via an EGFR transactivation pathway involving PKCδ. p66Shc links α1-ARs to an AKT signaling pathway that selectively phosphorylates/inactivates FOXO transcription factors and downregulates the ROS-scavenging protein manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD); the α1-AR-p66Shc-dependent pathway involving AKT does not regulate GSK3. Additional studies show that RNA interference–mediated downregulation of endogenous p66Shc leads to the derepression of FOXO3a-regulated genes such as MnSOD, p27Kip1, and BIM-1. p66Shc downregulation also increases proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression and induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, suggesting that p66Shc exerts an antihypertrophic action in neonatal cardiomyocytes. The novel α1-AR– and ROS-dependent pathway involving p66Shc identified in this study is likely to contribute to cardiomyocyte remodeling and the evolution of heart failure.

Keywords: p66Shc, α1-adrenergic receptors, protein kinase C, ROS, AKT

Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in response to mechanical forces or growth factors that activate intracellular signaling pathways. Hypertrophy has been classified as physiological/adaptive or pathological/maladaptive based on whether it progresses to frank cardiac failure. Physiological hypertrophy develops during normal postnatal development, exercise training, or pregnancy. This form of hypertrophy typically is not associated with functional derangements and has been attributed to a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway that phosphorylates targets such as GSK3 and FOXO transcription factors.1 In contrast, hypertension or valvular heart disease induce pathological forms of hypertrophy that progress to frank heart failure in part by activating heptahelical receptors, protein kinase (PK)C, and pathways that render the heart susceptible to apoptosis.1

This relatively broad classification of hypertrophy as physiological or pathological has been useful from an experimental standpoint. However, it fails to adequately describe most clinically reactive hypertrophies in humans which contain features of both hypertrophic phenotypes. The notion that all heptahelical receptors act in a stereotypical manner to trigger a similar hypertrophic response also is an oversimplification, because individual heptahelical receptors (such as the α1-adrenergic receptor [α1-AR] or protease-activated receptor-1) induce morphologically distinct forms of cardiac hypertrophy.2 Models that consider AKT as exclusively a mediator of adaptive/physiological hypertrophy also are inadequate, because AKT is activated by Gαq-coupled receptors that induce pathological hypertrophy and it recruits effectors that contribute to pathological remodeling under some experimental conditions.3 The effector responses activated by the Gαq-coupled receptor–dependent AKT signaling pathway remain uncertain.

p66Shc has recently emerged as a master regulator of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cardiovascular oxidative stress responses. p66Shc shares similar domain structure with p52Shc and p46Shc, adapter proteins that link receptor tyrosine kinases to growth regulatory pathways. All 3 Shc isoforms contain phospho-protein binding SH2 and PTB domains flanking a central CH1 domain that is the site for YY239/240 and Y317 phosphorylation (nomenclature based on human p52Shc). p66Shc contains an additional N-terminal extension that contains a phosphorylation site (S36) critical for the unique cellular function of p66Shc to amplify basal and stimulus-dependent ROS generation in mitochondria. Recent studies also implicate p66Shc in a redox-dependent pathway that sensitizes cells to proapoptotic stimuli by activating AKT, phosphorylating/inactivating FOXO transcription factors, and preventing the induction of antioxidant/free radical scavenging genes (such as manganese superoxide dismutase [MnSOD]4). This is distinct from the AKT-FOXO inactivation pathway recruited by trophic factors that promote cell survival by preventing the induction of proapoptotic genes (such as Fas ligand and the Bcl-2 family member Bim-1). This study implicates p66Shc in a redox-sensitive α1-AR pathway that couples to AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes.

Materials and Methods

Methods to prepare cardiomyocyte cultures from 2-day-old Wistar rats5,6 and methods to infect cultures with adenoviral constructs that drive expression of WT-PKCδ, KD-PKCδ, WT-PKCε, or β-galactosidase (β-gal)7 have been published. Infections with an Ad-p66ShcRNAi (that drives expression of a 19-mer sequence corresponding to bases 45 to 63 in the p66Shc unique N-terminal CH2 domain8) was performed in a similar manner. The detergent-free caveolae membrane isolation protocol and methods for immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis are published.5,6 Intracellular ROS was measured by fluorescence microscopy on cardiomyocytes loaded with dihydroethidium. A detailed description of all methods is provided in the expanded Materials and Methods section in an online data supplement, available at http://circres. ahajournals.org.

Results

α1-ARs Promote p66Shc-YY239/240 Phosphorylation in Cardiomyocytes

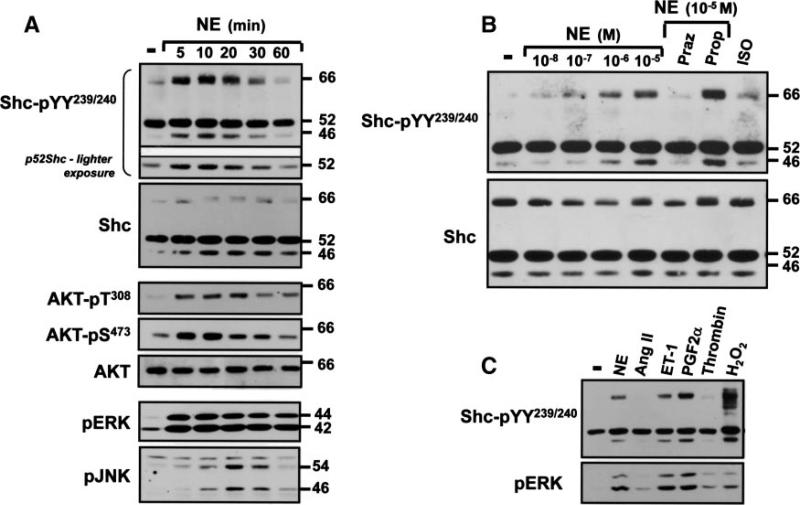

Shc phosphorylation mechanisms were examined in neonatal cardiomyocytes that coexpress p42Shc, p52Shc, and p66Shc.9 Figure 1A shows that p52Shc is constitutively YY239/240-phosphorylated in resting cardiomyocytes, whereas p66Shc- and p46Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is at the limits of detection under basal conditions. α1-AR activation with norepinephrine (NE) induces a prominent increase in p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation at 5 minutes that is sustained for another 10 to 15 minutes and wanes with continuous stimulation for 60 minutes. Although NE also increases p46Shc/p52Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation with similar kinetics, the magnitude of the NE-dependent increase in p52Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is modest (and evident only at lighter gel exposures).

Figure 1.

α1-ARs and selected other G protein–coupled receptors promote p66Shc tyrosine phosphorylation in cardiomyocytes. Stimulations were for the indicated intervals in A or 5 minutes in B and C with NE (1 μmol/L, or the indicated concentrations in B), 1 μmol/L angiotensin II (Ang II), 0.1 μmol/L endothelin-1 (ET-1), 1 μmol/L prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α), 1 U/mL thrombin, 5 mmol/L H2O2, or 0.1 μmol/L isoproterenol (ISO). Stimulations followed a pretreatment with prazosin (Praz) or propranolol (Prop) (each at 0.1 μmol/L) as indicated in B. Immunoblotting on cell lysates was with the indicated antibodies, with all results replicated in at least 3 separate culture preparations. Although propranolol induces a modest increase in NE-dependent p66Shc-pYY239/240 phosphorylation in B, this was not replicated in other experiments.

NE promotes AKT phosphorylation at T308 in the activation loop and S473 in the C terminus. NE-dependent AKT and p66Shc phosphorylation display identical time courses. NE also activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), but ERK activation is more sustained (for at least 60 minutes), and JNK activation is more delayed (Figure 1A). NE-dependent Shc tyrosine phosphorylation is via an α1-AR–dependent mechanism that is blocked by prazosin (α1-AR antagonist) and not propranolol (β-AR antagonist) (Figure 1B). β-AR activation with isoproterenol does not increase Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation.

Endothelin-1 and prostaglandin F2α mimic the effect of NE to increase Shc (predominantly p66Shc) YY239/240 phosphorylation (Figure 1C). p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is increased to an even greater extent by H2O2. Agonists for other heptahelical receptors such as angiotensin II and thrombin activate ERK without increasing Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation.

NE-Dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 Phosphorylation Is via an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Dependent Pathway

Because Shc proteins play well-recognized roles as adapters for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRs), and α1-ARs can transactivate EGFRs, we examined whether EGFRs link α1-ARs to p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation. Initial studies examined effects of ligands that directly activate EGFRs, namely EGF (ligand for EGFR/ErbB1) and heregulin (ligand for ErbB3 and ErbB4, receptors that heterodimerize with ErbB2). Figure I in the online data supplement shows that EGF increases YY239/240 phosphorylation on all 3 Shc isoforms; EGF also slows p66Shc mobility in SDS-PAGE. Effects of EGF are maximal at 5 minutes and wane by 1 hour; EGF activates ERK and AKT with similar kinetics. In contrast, heregulin increases p46Shc/p52Shc phosphorylation (and induces a robust/sustained increase in ERK and AKT phosphorylation), without increasing p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation. Basal and EGF-/heregulin-dependent responses are completely abrogated by AG1478 (EGFR kinase inhibitor); PP1 (inhibitor of SFKs and c-Abl) reduces basal, but not EGF-/heregulin-dependent, Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation. These results implicate p66Shc in the EGFR (but not ErbB2/ErbB4) signaling pathway.

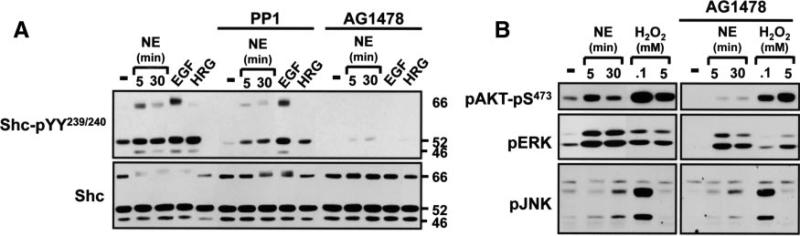

AG1478 induces a pronounced decrease in NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation (Figure 2A) and AKT activation (Figure 2B) but only a modest decrease in NE-dependent ERK activation (22±6%, n=5, P<0.5). AG1478 does not block the JNK activation pathway. NE and EGF pathways leading to p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation are not blocked by PP1 (Figure 2A and supplemental Figure I). Collectively, these results indicate that cardiac α1-ARs increase p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation via an AG1478-sensitive mechanism that is presumed to involve the EGFR (which also promotes p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation) and not other ErbB family members (which do not). This EGFR transactivation-p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation pathway links α1-ARs to AKT, but it plays only a minor role in α1-AR–dependent ERK activation (and it is not required for α1-AR–dependent JNK activation).

Figure 2.

EGFR activity is required for p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation. Immunoblotting is on cell lysates from cardiomyocytes pretreated for 30 minutes with vehicle, PP1 (10 μmol/L), or AG1478 (2 μmol/L) followed by stimulations for 5 minutes (unless indicated otherwise) with 100 nmol/L EGF, 100 nmol/L heregulin (HRG), 1 μmol/L NE, or the indicated H2O2 concentrations. Results were replicated in at least 3 separate culture preparations.

nPKC Isoform Activity Is Required for NE-Dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 Phosphorylation

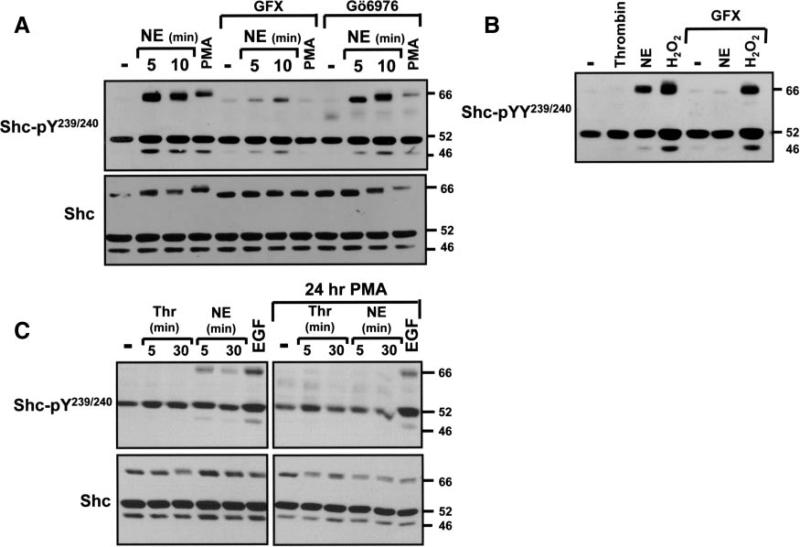

PKC isoforms comprise a family of enzymes that contribute to cardiac remodeling. We used PKC activators (phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate [PMA]) and inhibitors (GF109203X, Gö6976) as an initial strategy to explore the role of PKCs in the NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation pathway. Figure 3A shows that PMA mimics the effect of NE to increase p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation. PMA also decreases p66Shc mobility in SDS-PAGE (Figure 3A). NE- and PMA-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation (and agonist-dependent p66Shc band shifts) are abrogated by GF109203X (a relatively nonspecific inhibitor of PKC isoforms; Figure 3A and 3B). In contrast, the effect of 5 mmol/L H2O2 to promote Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation (on all 3 isoforms) is preserved in GF109203X-treated cultures, excluding a nonspecific inhibitory effect of GF109203X (Figure 3B). Gö6976 is a selective inhibitor of conventional PKC isoforms and PKD; Gö6976 attenuates PMA-dependent Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation without blocking NE-dependent Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation (Figure 3A). NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is abrogated by a 24-hour pretreatment with PMA (which downregulates phorbol ester-sensitive PKC isoforms); EGFR-dependent Shc-pYY239/240 phosphorylation persists under these conditions (Figure 3C). Collectively, these results implicate a novel (n)PKC (presumably PKCδ or PKCε) in the α1-AR–dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation pathway.

Figure 3.

NE promotes p66Shc tyrosine phosphorylation via an nPKC-dependent pathway. A and B, Immunoblotting on lysates from cultures pretreated with GF109203X (GFX) or Gö6976 (each at 5 μmol/L for 30 minutes) before challenge with vehicle, NE (10 μmol/L, for 5 minutes unless indicated otherwise), 1 U/mL thrombin, 300 nmol/L PMA, or 5 mmol/L H2O2. C, Stimulations followed a 24-hour pretreatment with vehicle or PMA. Control studies showing that GFX inhibits PKCs and chronic PMA treatment downregulates phorbol ester-sensitive PKCs are published.7

NE Promotes p66Shc-YY239/240 Phosphorylation via a PKCε-Dependent Mechanism in Caveolae

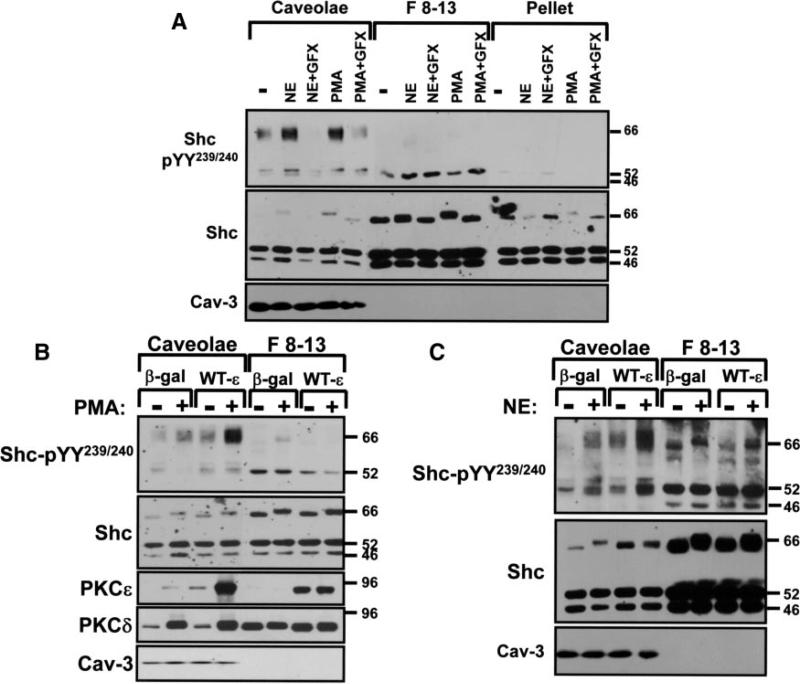

The observation that NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation requires EGFR and PKC activities provided the rationale to consider a role for caveolae; we previously implicated caveolae as signaling microdomains for PKC in cardiomyocytes and EGFRs localize to caveolae in other cell types.6 Caveolae were isolated using a biochemical fractionation scheme that separates buoyant cholesterol-/glycosphingolipid-enriched caveolae membranes from the bulk of the cellular material (cytosolic proteins, intracellular membranes, and noncaveolae surface membranes) that pellet to heavier gradient fractions (F8-13). Figure 4A shows that all 3 Shc isoforms partition predominantly to F8-13 gradient fractions in resting cardiomyocytes. Nevertheless, a pool of p46Shc/p52Shc and trace amounts of p66Shc are constitutively recovered (with some p52Shc- and p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation) in caveolae isolated from resting cardiomyocytes. NE and PMA increase p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation exclusively in caveolae (without altering p66Shc recovery in this fraction). Caveolae p66Shc-pYY239/240 immunoreactivity also increases in cardiomyocytes treated with diC8 (1,2-dioctanoyl-sn-glycerol) (a membrane-permeant analog of the endogenous PKC-activating lipid cofactor DAG; supplemental Figure II). Additional studies show that caveolae contain the bulk of the cellular EGFR protein immunoreactivity (supplemental Figure II) and that NE-/PMA- dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is blocked by GF109203X (Figure 4A). These results are consistent with the notion that NE promotes p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation via a mechanism that requires EGFR and PKC activities.

Figure 4.

NE and PMA increase p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation via a PKC-dependent mechanism in caveolae. Cardiomyocytes pretreated with vehicle or GF109203X (GFX) (5 μmol/L for 30 minutes) were challenged with 10 μmol/L NE (5 minutes) or 300 nmol/L PMA (20 minutes). Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer was used to overexpress WT-PKCε or β-gal as a control (multiplicity of infection, 100 pfu/cell) in B and C, with agonist treatments and caveolae isolation performed 48 hours after infections. Immunoblotting on caveolae (Cav), F8-13, and pellet fractions was as described in the expanded Materials and Methods section, with results replicated in 3 separate experiments.

We used adenoviruses that drive expression of wild-type (WT)-PKCε or WT-PKCδ, to identify the nPKC isoform that regulates p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation. Figure 4B shows that caveolae isolated from resting β-gal–infected cardiomyocytes contain a low level of PKCδ but no PKCε immunoreactivity; PMA drives PKCε and PKCδ to the caveolae fraction. The WT-PKCε transgene is detected at low levels in resting caveolae and in considerably higher amounts in caveolae from PMA-treated cardiomyocytes. WT-PKCε overexpression does not alter PKCδ or p66Shc protein partitioning between caveolae and noncaveolae fractions. Rather, Ad-WT-PKCε overexpression increases PMA- and NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation in the caveolae fraction (Figure 4B and 4C). Basal and agonist-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation are not influenced by WT-PKCδ overexpression (data not shown). These results implicate PKCε as the nPKC isoform that regulates p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation in caveolae.

NE Promotes p66Shc-YY239/240 Phosphorylation by Increasing ROS Generation

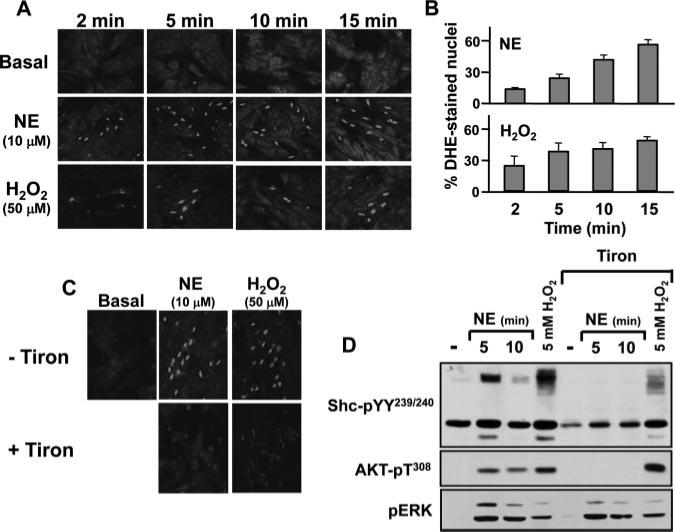

Recent studies in vascular models suggest that caveolae regulate growth responses at least in part by increasing ROS generation.10 Because ROS are implicated in EGFR transactivation pathways, ROS activate certain PKC isoforms, and ROS-dependent oxidative modifications have been implicated in α1-AR signaling in adult rat cardiomyocytes,11 we considered a role for ROS in the α1-AR-p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation pathway in neonatal cardiomyocytes. Intracellular ROS production was monitored with dihydroethidium (DHE), a nonfluorescent membrane-permeant probe that interacts with O2–, leading to the liberation of membrane-impermeant ethidium cations that fluoresce on intercalating with nuclear DNA. Figure 5A through 5C shows that NE increases nuclear DHE fluorescence; this effect is detected at 2 minutes, is sustained for at least 15 minutes, and is similar to the response to 50 μmol/L H2O2. NE- and H2O2-dependent increases in nuclear DHE fluorescence are prevented by Tiron, a membrane-permeable nonenzymatic superoxide scavenger (Figure 5C). Tiron also abrogates NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 and AKT phosphorylation; Tiron does not block NE-dependent ERK activation, indicating that Tiron is not a general nonspecific inhibitor of signaling by α1-ARs (Figure 5D). Tiron also attenuates Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation, but not ERK or AKT activation, in cardiomyocytes treated with a very high H2O2 concentration (5 mmol/L). These results implicate ROS in the α1-AR signaling pathway involving p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation that activates AKT, but not ERK, in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 5.

NE increases ROS accumulation, and NE-dependent p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is via a ROS-sensitive mechanism. A through C, Cardiomyocytes were incubated with the redox-sensitive indicator dihydroethidium (5 μmol/L) in the presence of vehicle or the indicated stimuli (without or with Tiron in C) and then imaged (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 543 nm cutoff) every 3 to 5 minutes. Agonist-dependent increases in the percentage of cells with DHE-stained nuclei are quantified in B (n=250 to 300 cells per assay condition; means±SEM) and was significant at all time points. C, Immunoblots on lysates from cardiomyocytes pretreated for 30 minutes with vehicle or 10 mmol/L Tiron followed by stimulation for 10 minutes with 10 μmol/L NE or 5 mmol/L H2O2. Results were replicated in 3 separate experiments.

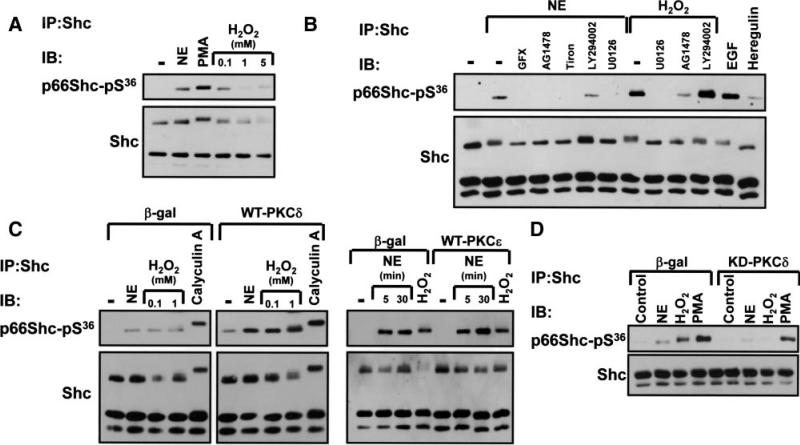

NE Promotes p66Shc-S36 Phosphorylation via a PKCδ-Dependent Mechanism

NE, PMA, and range of H2O2 concentrations (0.05 to 5 mmol/L) increase p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation (Figure 6A). Endothelin-1 and EGF also induce robust increases in p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation, whereas the response to heregulin (the ErbB3/4 agonist) is relatively modest in magnitude (Figure 6B and data not shown). Phosphatase inhibition with calyculin A also increases p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation and leads to a massive p66Shc mobility shift, far in excess of the mobility shift elicited by other agonists (Figure 6C). This presumably is attributable to phosphorylation at multiple sites, not just S36.

Figure 6.

p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation is augmented by PKCδ overexpression. Cardiomyocytes were stimulated with 10 μmol/L NE, 300 nmol/L PMA, 5 mmol/L H2O2, or 0.1 μmol/L calyculin A as indicated. Stimulation followed pretreatment with 5 μmol/L GFX, 2 μmol/L AG1478, 10 mmol/L Tiron, 10 μmol/L LY294002, or 5 μmol/L U0126 in B or adenoviral-mediated WT-PKCδ, WT-PKCε, KD-PKCδ, or β-gal overexpression in C and D. Shc was immunoprecipitated and equal amounts of protein (derived from 600 mg of starting cell extract) was subjected to immunoblotting for p66Shc-pS36 and Shc protein immunoreactivity (to verify equal protein recovery and loading). Immunoblotting to track Shc protein recovery was performed on 5-fold less material in D, because of limited amounts of protein. Only the smaller p46/p52Shc isoforms are detected under these conditions. All results were replicated in 3 separate cultures.

Pharmacological studies show that NE- and H2O2-dependent increases in p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation are blocked by AG1478 and U0126 (Figure 6B); U0126 also attenuates p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation by PMA (data not shown). These results implicate ERK as the proline-directed kinase that phosphorylates p66Shc at S36 (a site with a proline in the +1 position). p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation is not blocked by LY294002, a phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor that prevents AKT activation. NE-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation is inhibited by Tiron and GF109203X (Figure 6B); GF109203X also inhibits p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation by PMA (data not shown). These results are consistent with recent studies that attribute p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation to PKC; although previous studies focused on PKCβ, an additional or alternate role for PKCδ was not excluded.12 Figure 6C shows that basal- and agonist-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation is increased by WT-PKCδ, but not WT-PKCε. Figure 6D shows that NE- and H2O2-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation is blocked by KD-PKCδ, whereas PMA-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation persists in KD-PKCδ cultures. These results implicate PKCδ in α1-AR- and H2O2-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation pathways.

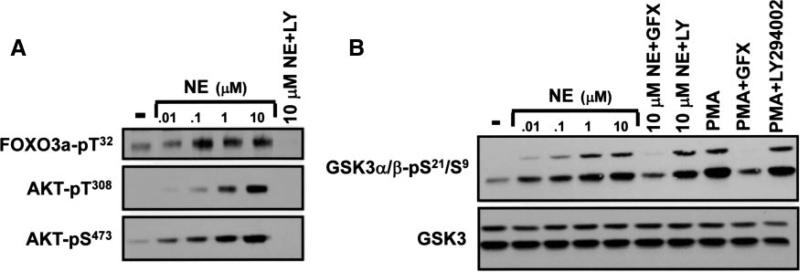

The NE-Dependent AKT Signaling Pathway Regulates FOXO3a, but Not GSK3, Phosphorylation

Figure 7A shows that NE activates AKT in a dose-dependent manner and that FOXO3a-T32 phosphorylation (a modification that has been attributed to AKT) increases in parallel. As recently reported by Ni et al,13 T32-phosphorylated FOXO3a accumulates in the cytosol of NE-treated cardiomyocytes (data not shown). NE treatment also increases GSK3 phosphorylation (Figure 7B). However, pharmacological studies provided unanticipated evidence that LY294002 abrogates NE-dependent AKT and FOXO3a-T32 phosphorylation, without blocking GSK3 phosphorylation. Additional studies show that PMA also increases GSK3 phosphorylation, without activating AKT. NE- and PMA-dependent GSK3 phosphorylation are blocked by GF109203X. These results indicate that agonist-dependent GSK3 activation is via a PKC-dependent mechanism that does not require phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase or AKT activity. Collectively, these studies expose heretofore unrecognized signaling specificity, showing that the NE-dependent AKT signaling pathway selectively couples to the phosphorylation of FOXO3a, but not GSK3.

Figure 7.

NE-dependent phosphorylation of AKT, GSK3, and FOXO3a. Immunoblotting on lysates from cardiomyocytes stimulated with the indicated concentrations of NE or 300 nmol/L PMA for 10 minutes. Stimulations followed pretreatment with vehicle, LY294002 (LY) or GF109203X (GFX) as indicated. Results were replicated in 3 experiments.

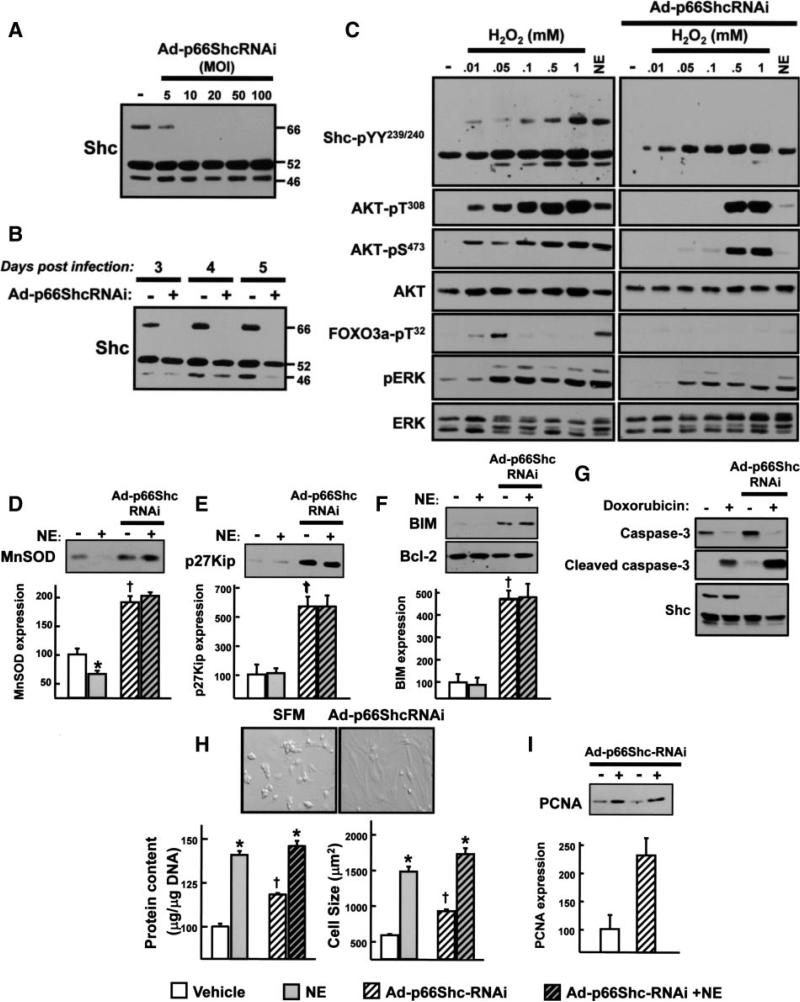

p66Shc Links α1-ARs to the AKT-FOXO3a-T32 Phosphorylation Pathway and Regulates Cardiomyocyte Growth

The final set of studies used gene silencing, with an adenovirus that selectively downregulates p66Shc (Ad-p66ShcRNAi) to explore the role of p66Shc in α1-AR signaling responses. Figure 8A and 8B show that Ad-p66ShcRNAi treatment at a multiplicity of infection as low as 10 leads to a profound downregulation of p66Shc, but not p52/p46Shc, expression that persists for at least 48 hours.

Figure 8.

Ad-p66ShcRNAi downregulates p66Shc protein expression and inhibits the NE- and low H2O2-dependent AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation pathways. Ad-p66ShcRNAi infection was performed on culture day 1 at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) (A) or a multiplicity of infection of 40 (B through I). C, Stimulation was with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 or 10 μmol/L NE (each for 10 minutes) at day 3 following infection with Ad-p66ShcRNAi or empty vector. D through F, H, and I, Treatment was with vehicle or 10 μmol/L NE for 3 days (starting at culture day 1). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting for MnSOD, p27Kip, BIM, Bcl-2, or PCNA (D through F and I), with a typical experiment depicted on top and the results quantified on the bottom (n=3, *P<0.05 NE vs vehicle; †P<0.05 Ad-p66ShcRNAi vs empty vector). G, Immunoblotting on cell lysates from cardiomyocytes treated for 48 hours with vehicle or doxorubicin (1 μmol/L for 48 hours). H, Measurements of cell size (by phase-contrast microscopy) and protein synthesis were as described in the expanded Materials and Methods section. Results were replicated in 3 experiments.

Figure 8C shows that NE and physiological low H2O2 concentrations (10 to 50 μmol/L) exert similar effects to increase p66Shc-YY239/240, AKT-T308/S473, FOXO-T32, and ERK phosphorylation and that the AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation pathways activated by NE and low H2O2 concentrations are abrogated by p66Shc downregulation. In contrast, high H2O2 concentrations (0.1 to 1 mmol/L) also increase p66Shc-YY239/240, AKT-T308/S473, and ERK phosphorylation, but this is via a different mechanism that does not lead to FOXO3a-T32 phosphorylation; it is not inhibited by p66Shc downregulation. Agonist-dependent p52Shc-YY239/240 and ERK phosphorylation pathways also persist in Ad-p66ShcRNAi cultures. Control experiments show that p66Shc knockdown does not lead to changes in the expression of signaling proteins that might indirectly influence α1-AR signaling responses such as PKCδ, PKCε, or caveolin-3 (supplemental Figure III). Collectively, these results indicate that p66Shc couples α1-ARs and physiologically low H2O2 concentrations to the AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation pathway.

We examined whether the NE-dependent AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation pathway influences FOXO3a target gene expression. Figure 8D shows that NE induces a modest decrease in the expression of MnSOD (an antioxidant scavenger that limits oxidative stress). Other FOXO3a targets such as the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p27Kip1 that regulates cell cycle and the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bim-114 are expressed at very low levels and are not regulated by NE (Figure 8E and 8F). However, p66Shc downregulation prevents the NE-dependent decrease in MnSOD expression and leads to a general derepression of FOXO3a targets such as MnSOD, p27Kip1, and BIM-1; Bcl-2 expression is not affected by p66Shc downregulation (Figure 8D through 8F).

The functional consequences of the Ad-p66ShcRNAi treatment are difficult to predict; a decrease in the direct proapoptotic actions of p66Shc in mitochondria and derepression of cytoprotective FOXO3a-regulated genes such as MnSOD might be cytoprotective, but this could be offset by a decrease in signaling via the AKT pathway and an increase in the proapoptotic actions of BIM-1. Therefore, we examined whether p66Shc modulates the proapoptotic effects of doxorubicin, a chemotherapeutic agent that increases oxidant production and induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Figure 8G shows that doxorubicin treatment leads to prominent cleavage of caspase-3 in both vector and Ad-p66ShcRNAi cultures; in each case, this is associated with gross morphological evidence of cell death (data not shown). The lack of protection against doxorubicin-dependent apoptosis in Ad-p66ShcRNAi cultures cannot be attributed to a defect in AKT activation (which typically mitigates the doxorubicin-dependent proapoptotic response); doxorubicin-dependent AKT activation is not decreased by p66Shc downregulation (supplemental Figure IV).

An effect of p66Shc downregulation to derepress FOXO targets such as p27Kip1 and “atrogenes” (proteins that inhibit hypertrophy) is predicted to limit cardiomyocyte growth.15,16 However, Figure 8H provides surprising evidence that p66Shc downregulation markedly increases basal cell size and protein content. Of note, NE increases cell size and protein content in Ad-p66ShcRNAi cultures (to a level that is comparable to the cell size and protein content in Ad-β-gal cultures). The observation that NE-dependent hypertrophy is preserved in Ad-p66ShcRNAi cultures that exhibit a defect in NE-dependent AKT activation indicates that AKT is not required for α1-AR-dependent cardiac hypertrophy. The mechanism(s) underlying the growth promoting effects of p66Shc downregulation is uncertain. Figure 8I shows that p66Shc downregulation increases proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression. Although this might encourage entry into the cell cycle, an effect of Ad-p66ShcRNAi treatment to induce gross changes in DNA content or cell number was not detected (data not shown).

Discussion

p66Shc has recently emerged as a master regulator of intracellular ROS production and cardiovascular oxidative stress responses. Recent studies identify a p66Shc electron transfer reaction with cytochrome c that enhances basal and stimulus-dependent ROS accumulation and promotes cell death.12,17–19 Studies reported herein indicate that p66Shc exerts an additional role as a redox-sensitive target of the α1-AR. The results of this study (schematized in supplemental Figure V) show that α1-ARs increase ROS accumulation and promote p66Shc-YY239/240 and S36 phosphorylation via a ROS-dependent mechanism that requires the cooperative effects of PKCε and PKCδ. p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is localized to caveolae and increased by PKCε overexpression. The mechanism linking PKCε to increased p66Shc-YY239/240 phosphorylation is uncertain but could involve the inhibition of a tyrosine phosphatase. α1-ARs also activate a PKCδ-dependent pathway that promotes p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation. However, a direct role for PKCδ asaS36 kinase is unlikely, because S36 lies in mitogen-activated protein kinase (not a PKC) consensus phosphorylation motif and agonist-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation is blocked by a MEK inhibitor. A previous study implicated PKCβ in an H2O2-dependent pathway leading to p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation. However, it is important to note that there is compelling evidence that PKCδ mimics PKCβs effects on mitochondrial calcium/apoptosis responses12; previous efforts to determine whether PKCδ controls p66Shc function were inconclusive, because the studies relied on rottlerin (an ineffective inhibitor of PKCδ20). Our results implicate PKCδ in the agonist-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation pathway. It is interesting to speculate that S36 phosphorylation is confined to the pool of YY239/240-phosphorylated p66Shc in caveolae. The role of caveolae in the PKCδ-dependent p66Shc-S36 phosphorylation pathway is the focus of ongoing studies. The observation that PKCε and PKCδ cooperate to regulate p66Shc phosphorylation deserves emphasis. Most studies have assigned opposing roles to PKCε and PKCδ in ischemia/reperfusion, showing that PKCδ promotes oxidative stress, apoptosis, and inflammation (hallmarks of reperfusion injury) and that PKCε mimics preconditioning. A simple model that links PKCε exclusively to cardioprotection and PKCδ to reperfusion injury does not accommodate these cooperative actions of PKCε and PKCδ in the control of p66Shc.

Recent studies implicate p66Shc in a ROS-dependent mechanism that inhibits FOXO activity. This study identifies a similar role for p66Shc in a ROS-sensitive α1-AR pathway that increases AKT phosphorylation, inactivates FOXO3a, and decreases MnSOD expression. These results suggest that p66Shc can exert proapoptotic actions both by increasing ROS production (when complexed with cytochrome c in mitochondria) and by decreasing ROS detoxification (by activating the AKT-FOXO3a pathway that regulates MnSOD expression). The α1-AR subtype that activates this ROS-p66Shc-AKT-FOXO3a pathway and the role of this α1-AR pathway in adult cardiomyocytes requires further study. In particular, it is interesting to note that α1-AR activation of the AKT-FOXO3a pathway has not been detected in adult cardiomyocytes that lack p66Shc expression.9 Because p66Shc expression is induced by hypertrophic stimuli and oxidative stresses,9 it will be interesting to examine whether α1-ARs recruit the AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation pathway and repress antioxidant gene expression exclusively in diseased adult cardiomyocytes that express the p66Shc protein.

This study identifies a novel α1-AR-ROS-p66Shc-AKT signaling pathway that selectively couples to the phosphorylation/inactivation of FOXO3a; this mode of AKT activation does not lead to GSK3 phosphorylation. A mechanism that selectively targets AKT to FOXO3a, but not GSK3, phosphorylation has not been reported. Although previous studies in nonmyocytes suggest that AKT signaling specificity can be regulated through phosphorylation at S473 in the C terminus (which is required for phosphorylation of FOXO3a, but not GSK321), this mechanism would not account for the signaling specificity identified in our study; AKT is dually phosphorylated at T308 and S473 in NE-treated cardiomyocytes. Other differences in AKT phosphorylation patterns, AKT interactions with binding partners, and/or AKT localization might impart specificity and should be considered.

This study identifies an α1-AR-ROS-p66Shc-AKT-FOXO3a phosphorylation pathway that decreases MnSOD expression and is predicted to impair ROS detoxification and enhance apoptosis; the deleterious consequences of AKT activation via this α1-AR-dependent pathway would be quite distinct from the cardioprotective actions of AKT when activated by various other growth factors. These stimulus-specific differences in AKT actions may be pertinent to the lingering controversies that cloud the interpretation of overexpression studies, where AKT has been implicated in cardiomyocyte growth, cardiomyocyte survival (without evidence of hypertrophy), or cardiac dysfunction, depending on the level, location, or chronicity of AKT transgene expression. Our studies emphasize that AKT can elicit functionally divergent responses that result in distinct biological outcomes; these cell- or stimulus-specific responses tend to be obscured by overexpression strategies.

Finally, this study implicates p66Shc in the control of FOXO3a-regulated gene products such as MnSOD, p27Kip1, and BIM-1. We also show that p66Shc inhibits the expression of the cell cycle regulatory protein PCNA (which might explain the increase in the number of cycling cardiomyocytes previously detected in p66Shc–/– hearts22). Finally, we identify a role for p66Shc as a negative regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy; this results was not anticipated, because a recent study did not detect a difference in cardiomyocyte size between WT and p66Shc–/– mice.23 However, an antihypertrophic effect of p66Shc in cardiomyocytes might be analogous to the antimitogenic effect of p66Shc identified in lymphocytes.24 Our studies also provide surprising evidence that p66Shc downregulation is not cytoprotective in doxorubicin-treated cardiomyocytes. This result runs counter to the current opinion that pharmacological therapies that inhibit p66Shc expression or action act as panaceas for clinical disorders characterized by increased oxidative stress.25–28 However, our findings resonate with recent evidence that p66Shc can exert pleiotropic effects on a range of seeming unrelated fundamental biological processes involving cellular adhesion, cytoskeletal morphology, and intracellular calcium homeostasis29,30 and that p66Shc exerts an antiapoptotic effect by activating a Notch-3 pathway that enhances human stem/progenitor cell survival.31 These more nuanced and cell-specific effects of p66Shc are predicted to be important for stem cell-mediated tissue renewal and tissue remodeling, perhaps explaining why a protein such as p66Shc, that plays such a deleterious role in the pathogenesis of age-related diseases characterized by increased oxidative stress, has been conserved during evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants HL77860, HL67101, and T32 HL76116.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Aronow BJ, Toyokawa T, Canning A, Haghighi K, Delling U, Kranias E, Molkentin JD, Dorn GW. Divergent transcriptional responses to independent genetic causes of cardiac hypertrophy. Physiol Genomics. 2001;6:19–28. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.2001.6.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sabri A, Muske G, Zhang H, Pak E, Darrow A, Andrade-Gordon P, Steinberg SF. Signaling properties and functions of two distinct cardiomyocyte protease-activated receptors. Circ Res. 2000;86:1054–1061. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.10.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiojima I, Walsh K. Regulation of cardiac growth and coronary angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3347–3365. doi: 10.1101/gad.1492806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nemoto S, Finkel T. Redox regulation of forkhead proteins through a p66shc-dependent signaling pathway. Science. 2002;295:2450–2452. doi: 10.1126/science.1069004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rybin VO, Xu X, Lisanti MP, Steinberg SF. Differential targeting of β-adrenergic receptor subtypes and adenylyl cyclase to cardiomyocyte caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:41447–41457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybin VO, Xu X, Steinberg SF. Activated protein kinase C isoforms target to cardiomyocyte caveolae. Circ Res. 1999;84:980–988. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rybin VO, Sabri A, Short J, Braz JC, Molkentin JD, Steinberg SF. Cross regulation of nPKC isoform function in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14555–14564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamori T, White AR, Mattagajasingh I, Khanday FA, Haile A, Qi B, Jeon BH, Bugayenko A, Kasuno K, Berkowitz DE, Irani K. p66shc regulates endothelial NO production and endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation: implications for age-associated vascular dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39:992–995. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obreztchikova M, Elouardighi H, Ho M, Wilson BA, Gertsberg Z, Steinberg SF. Distinct signaling functions for SHC isoforms in the heart. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20194–20204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601859200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang B, Oo TN, Rizzo V. Lipid rafts mediate H2O2 prosurvival effects in cultured endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:1501–1503. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5359fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao L, Pimentel DR, Wang J, Singh K, Colucci WS, Sawyer DB. Role of reactive oxygen species and NAD(P)H oxidase in α1-adrenoceptor signaling in adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:C926–C934. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00254.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Contursi C, Minucci S, Mantovani F, Wieckowski MR, Del Sal G, Pelicci PG, Rizzuto R. Protein kinase C-β and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science. 2007;315:659–663. doi: 10.1126/science.1135380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni YG, Berenji K, Wang N, Oh M, Sachan N, Dey A, Cheng J, Lu G, Morris DJ, Castrillon DH, Gerard RD, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Foxo transcription factors blunt cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting calcineurin signaling. Circulation. 2006;114:1159–1168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.637124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl M, Dijkers PF, Kops GJPL, Lens SMA, Coffer PJ, Burgering BMT, Medema RH. The forkhead transcription factor FoxO regulates transcription of p27Kip1 and Bim in response to IL-2. J Immunol. 2002;168:5042–5031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauck L, Harms C, Rohne J, Gertz K, Dietz R, Endres M, von Harsdorf R. Protein kinase CK2 links extracellular growth factor signaling with the control of p27(Kip1) stability in the heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:315–324. doi: 10.1038/nm1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skurk C, Izumiya Y, Maatz H, Razeghi P, Shiojima I, Sandri M, Sato K, Zeng L, Schiekofer S, Pimentel D, Lecker S, Taegtmeyer H, Goldberg AL, Walsh K. The FOXO3a transcription factor regulates cardiac myocyte size downstream of AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20814–20823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500528200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Moroni M, Contursi C, Raker VA, Piccini D, Martin-Padura I, Pelliccia G, Trinei M, Bono M, Puri C, Tacchetti C, Ferrini M, Mannucci R, Nicoletti I, Lanfrancone L, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG. The life span determinant p66Shc localizes to mitochondria where it associates with mitochondrial heat shock protein 70 and regulates transmembrane potential. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:25689–25695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, Paolucci D, Moroni M, Contursi C, Pelliccia G, Luzi L, Minucci S, Marcaccio M, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Bernardi P, Paolucci F, Pelicci PG. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 2005;122:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nemoto S, Combs CA, French S, Ahn BH, Fergusson MM, Balaban RS, Finkel T. The mammalian longevity-associated gene product p66shc regulates mitochondrial metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10555–10560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511626200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soltoff SP. Rottlerin: an inappropriate and ineffective inhibitor of PKCδ. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polak P, Hall MN. mTORC2 Caught in a SINful Akt. Dev Cell. 2006;11:433–434. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graiani G, Lagrasta C, Migliaccio E, Spillmann F, Meloni M, Madeddu P, Quaini F, Padura IM, Lanfrancone L, Pelicci P, Emanueli C. Genetic deletion of the p66Shc adaptor protein protects from angiotensin II-induced myocardial damage. Hypertension. 2005;46:433–440. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000174986.73346.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rota M, LeCapitaine N, Hosoda T, Boni A, De Angelis A, Padin-Iruegas ME, Esposito G, Vitale S, Urbanek K, Casarsa C, Giorgio M, Luscher TF, Pelicci PG, Anversa P, Leri A, Kajstura J. Diabetes promotes cardiac stem cell aging and heart failure, which are prevented by deletion of the p66Shc gene. Circ Res. 2006;99:42–52. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000231289.63468.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finetti F, Pellegrini M, Ulivieri C, Savino MT, Paccagnini E, Ginanneschi C, Lanfrancone L, Pellicci PG, Baldari CT. The proapoptotic and antimitogenic protein p66SHC acts as a negative regulator of lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity. Blood. 2008;111:5017–5027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andoh T, Lee SY, Chiueh CC. Preconditioning regulation of bcl-2 and p66shc by human NOS1 enhances tolerance to oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2000;14:2144–2146. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0151fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaccagnini G, Martelli F, Fasanaro P, Magenta A, Gaetano C, Di Carlo A, Biglioli P, Giorgio M, Martin-Padura I, Pelicci PG, Capogrossi MC. p66ShcA modulates tissue response to hindlimb ischemia. Circulation. 2004;109:2917–2923. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129309.58874.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Napoli C, Martin-Padura I, De Nigris F, Giorgio M, Mansueto G, Somma P, Condorelli M, Sica G, De Rosa G, Pelicci P. Deletion of the p66Shc longevity gene reduces systemic and tissue oxidative stress, vascular cell apoptosis, and early atherogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2112–2116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0336359100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francia P, delli Gatti C, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, Savoia C, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Schiavoni M, Luscher TF, Volpe M, Cosentino F. Deletion of p66shc gene protects against age-related endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2004;110:2889–2895. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147731.24444.4D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pellegrini M, Finetti F, Petronilli V, Ulivieri C, Giusti F, Lupetti P, Giorgio M, Pelicci PG, Bernardi P, Baldari CT. p66SHC promotes T cell apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired Ca2+ homeostasis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:338–347. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petti LM, Ricciardi EC, Page HJ, Porter KA. Transforming signals resulting from sustained activation of PDGFβ receptor in mortal human fibroblasts. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1172–1182. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sansone P, Storci G, Giovannini C, Pandolfi S, Pianetti S, Taffurelli M, Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Chieco P, Bonafe M. p66Shc/Notch-3 interplay controls self-renewal and hypoxia survival in human stem/progenitor cells of the mammary gland expanded in vitro as mammospheres. Stem Cells. 2007;25:807–815. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.