Abstract

The Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway plays multiple essential roles during metazoan development, homeostasis, and disease. Although core protein components are highly conserved, the variations in Hh signal transduction mechanisms exhibited by existing model systems (Drosophila, fish, and mammals) are difficult to understand. We characterize the Hh pathway in planarians. Hh signaling is essential for establishing the Anterior/Posterior axis during regeneration by modulating wnt expression. Moreover, RNAi methods to reduce signal transduction proteins Cos2/Kif27/Kif7, Fused, or Iguana do not result in detectable Hh signaling defects; however, these proteins are essential for planarian ciliogenesis. Our study expands the understanding of Hh signaling in the animal kingdom and suggests an ancestral mechanistic link between Hh signaling and the function of cilia.

The Hh signaling pathway plays numerous evolutionarily conserved roles in the regulation of cell growth and patterning during the embryonic and postembryonic development of animals as diverse as frutiflies and humans. The misregulation of this pathway has equally profound consequences resulting in defects such as holoprosencephaly (cyclopia) and tumorigenesis. Secreted Hh protein alters gene transcription by binding the cell-surface receptor Patched (Ptc), preventing repression of the 7 membrane spanning receptor Smoothened (Smo) by Ptc. This activates Gli transcription factors and inactivates their inhibitor Suppressor of Fused (SuFu). Despite conservation of these core components and their mode of function (1, 2), Hh signal transduction mechanisms appear to have diversified throughout evolution (3). Drosophila Hh signaling is cilia-independent and requires the kinesin Costal2 (4) (Kif7/27 in vertebrates) and the kinase Fused (5). The mouse Hh pathway requires primary cilia (6, 7) and Kif7 (8–10), but not Fused (11, 12). Zebrafish utilize cilia, Kif7, Fused, and Iguana/Dzip1 (Igu) (13–19). C. elegans has lost a functional Hh pathway altogether (20). Since planarians belong to a group of animals that evolved independently from flies, fish, and mammals (Sup. Fig. 1) an analysis of planarian Hh signaling could reveal how the mechanistic differences in a highly conserved signaling pathway arose.

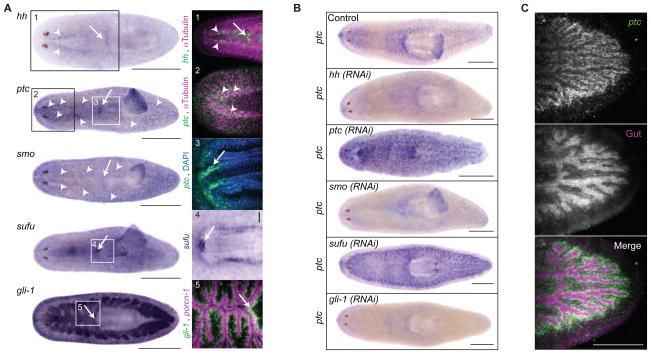

Systematic sequence homology searching of the S. mediterranea genome identified single homologs for planarian Hh (Smed-hh), Patched (Smed-ptc), Smoothened (Smed-smo) and Supressor of Fused (Smed-sufu), but three Gli homologs (37) (Sup. Fig. 2,3). Of the Gli homologs, only Smed-gli-1 exhibited an obvious role in Hh signaling (see below). We cloned (see SOM) and analyzed the expression of these planarian Hh components by in-situ hybridization (Fig. 1A–C, Sup. Fig. 4). ptc expression was reduced by RNAi of pathway activators (hh, smo, gli-1) and elevated by RNAi of pathway inhibitors (ptc, sufu) (Fig. 1B), suggesting that as in other animals (21–23), ptc is a Hh target in planarians and its expression marks sites of Hh signaling. Complementary expression of ptc, hh, and smo throughout the central nervous system (CNS), and hh, ptc, smo, sufu, and gli-1 near the root of the pharynx implicates these locations as possible sites of Hh activity (Fig. 1A, Sup. Fig. 4). gli-1 expression in cells surrounding the gut enterocytes (Fig. 1A) and particularly strong ptc upregulation upon sufu(RNAi) in the same region (Fig. 1C) may indicate a conserved function of Hh in the gastrovascular system (24, 25). Additionally, mitotic activity was increased by ptc(RNAi) and sufu(RNAi), but decreased by hh(RNAi) (Sup. Fig. 5, 6), mirroring the mitotic effects of Hh in other organisms (26, 27). Altogether, these initial studies suggest that planarian Hh signaling likely has diverse functions in various adult tissues.

Fig. 1.

Planarian Hedgehog signaling. (A) Gene expression in intact animals. Boxes magnified on right. 1: Epifluorescence image, hh (green), CNS (magenta, anti-α-Tubulin). 2: Confocal image, ventral head: ptc (green). CNS (magenta, anti-α-Tubulin). 3: Root of pharynx: ptc (green). Nuclei (Blue, DAPI). 4: sufu expression near root of pharynx. 5: gli-1 (green), gut epithelium (magenta, Smed-porcn-1 and Smed-sialin). Scale bar, 0.5 mm. Arrow heads, VNC. Arrow, root of pharynx. (B) ptc expression in RNAi-treated intact animals. The seemingly paradoxical up-regulation of ptc upon ptc(RNAi) results from the massive promotion of Hh signaling by ptc(RNAi). Scale bar, 0.5 mm. (C) ptc expression confocal images in sufu(RNAi) intact animals. Scale bar, 0.2 mm.

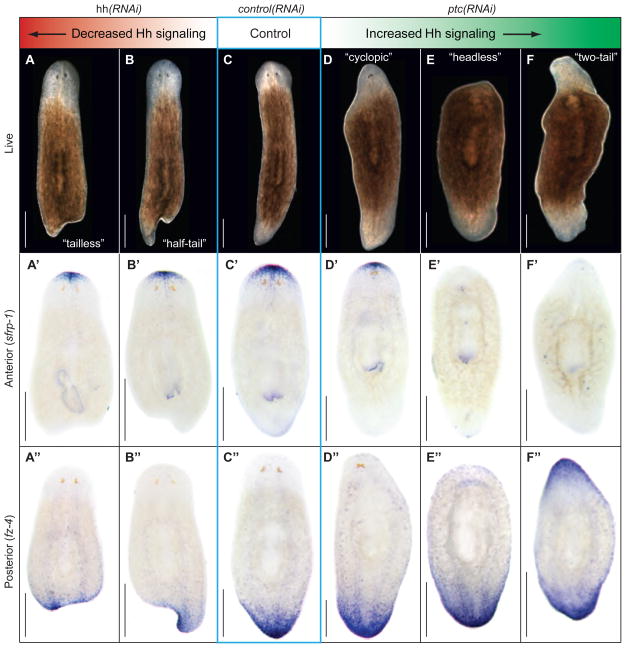

To test whether the Hh pathway contributes to the signaling network orchestrating planarian regeneration, we amputated the heads and tails of dsRNA-fed animals. Targeting the pathway activator hh left anterior regeneration unaffected, but caused a range of posterior regeneration defects including reduced or absent tail tissue and concomitant changes in posterior marker expression (Fig. 2A-B”, Sup. Fig. 7). Conversely, RNAi against the pathway inhibitor ptc left posterior regeneration unaffected, but caused anterior specific defects, including tail instead of head formation and striking changes in marker expression (Fig. 2D-F”, Sup. Fig. 7; Sup. Movies 1 and 2). Targeting gli-1 and smo produced identical regeneration phenotypes to hh(RNAi), and sufu(RNAi) resembled ptc(RNAi) (Sup. Fig. 8), establishing tail or head regeneration defects as general consequence of decreased or increased Hh signaling, respectively. Systematic RNAi-dosage experiments ranked the range of phenotypes according to severity. Three observations are particularly noteworthy. First, “headless” animals expressed neither head nor tail markers anteriorly (Fig. 2E’, E”), but expressed a marker for intermediate anterior cell fate (Sup. Fig. 9), reminiscent of dose-dependent roles for Hh in other contexts (28). Second, “cyclopic” animals resulted from increased Hh signaling. The same phenotype occurs in vertebrates (29), but is caused by decreased Hh signaling. This difference, along with lack of expression of Smed-hh along the planarian midline, suggests that the midline function of Hh in vertebrates is not conserved in planarians. Third, SuFu has a prominent role in planarians, which is similar to vertebrates but different from Drosophila (30). RNAi-combination of two pathway activators or inhibitors enhanced the respective phenotypes whereas activator-inhibitor combinations suppressed each other (Sup. Fig. 10). However, besides the expected and predominant function of Smo as a pathway activator, these experiments also indicated a cryptic inhibitory activity, but the mechanistic basis of this effect is currently unclear. Combined with regeneration time course experiments showing that Hh-related phenotypes originate during early phases of regeneration (Sup. Fig. 11), our data demonstrate that the different phenotypic classes resulting from altered Hh signaling constitute a series of A/P patterning defects, and that early Hh signaling is necessary and sufficient for tail regeneration.

Fig. 2.

Mis-regulated Hh signaling results in A/P patterning defects. (A–F) Live images of regenerating trunk fragments 14d after amputation. Decreased Hh signaling achieved by hh(RNAi) (A–B”), and increased signaling by ptc(RNAi) (D–F”). Phenotypes are arranged according to severity. (A’–F’). Expression of anterior marker (Smed-sFRP-1; (31, 33)). (A”–F”) Expression of posterior marker (Smed-fz-4; (31)).

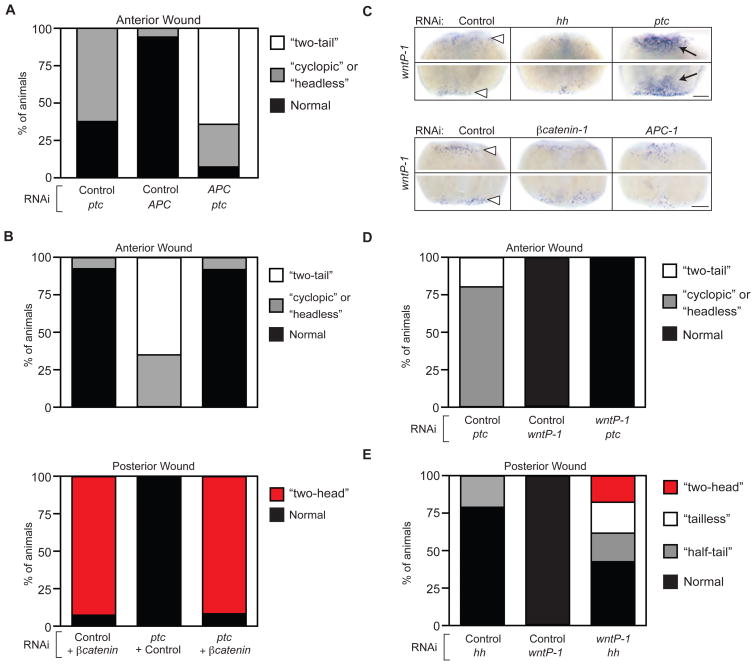

The early requirements for elevated Hh signaling in tails and reduced Hh signaling in heads mirrors those for β-catenin signaling (31–33). In addition, diluted dosages of APC-1(RNAi), which elevateβ-catenin activity (31) produced a range of phenotypes remarkably similar to ptc(RNAi) (Sup. Fig. 12). Combining doses of ptc(RNAi) and APC-1(RNAi) that by themselves elicited only weak defects led to a striking increase in phenotype severity (Fig. 3A). Moreover, a single feeding of βcatenin-1(RNAi) in ptc(RNAi)-fed animals completely suppressed the ptc(RNAi) “two-tail” phenotype, causing head formation at both anterior and posterior wounds (Fig. 3B). Thus, the Hh and β-catenin pathways synergize functionally to specify tails, and tail induction by elevated Hh signaling depends on β-catenin activity.

Fig. 3.

Hh specifies A/P fate via interaction with Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (A, B) Quantification of double-RNAi experiments scored for anterior or posterior regeneration defects. Relative frequency of indicated phenotypes in a cohort of trunk fragments scored 14d after amputation. (A) N>15 animals/condition. (B) N>20 animals/condition. (C) wntP-1 expression at 1d post-amputation. White arrowheads, expression at both anterior (upper panels of each set) and posterior (lower panels of each set) wounds in control animals. Black arrows, upregulated expression in ptc(RNAi). Scale bars, 0.2 mm. (D, E) Quantification of double-RNAi experiments scored for (D) anterior and (E) posterior regeneration defects. Relative frequency of indicated phenotypes in trunk fragment cohort scored 14d after amputation. N>21 animals/condition.

Because a Wnt ligand (Smed-wntP-1) was recently implicated in activating β-catenin during tail regeneration (34), we examined whether wnt expression was regulated by Hh signaling. One day after amputation, wntP-1 expression was reduced in hh(RNAi) animals and strongly increased in ptc(RNAi) animals (Fig. 3C, top). In contrast, wntP-1 expression was not altered inβcatenin-1(RNAi) or APC-1(RNAi) animals (Fig. 3C, bottom), ruling out indirect polarity-associated effects. Expression of an additional wnt gene functioning in tail regeneration (Smed-wnt11-2) (34), showed a dependence on both Hh and β-catenin pathway activity (Sup. Fig. 13). Unchanged ptc expression in βcatenin-1(RNAi) or APC-1(RNAi) animals suggested that β-catenin may not reciprocally control Hh signaling (Sup. Fig. 14). wntP-1(RNAi) suppressed the ptc(RNAi) phenotypes at anterior wounds (Fig. 3D) and strongly enhanced the hh(RNAi) phenotypes at posterior wounds, synergistically leading to the appearance of a posterior head in 20% of wntP-1(RNAi);hh(RNAi) animals (Fig. 3E). These data indicate that Hh-mediated wntP-1 expression is likely responsible for the posteriorizing effect of ptc(RNAi) and that improved hh(RNAi) efficiency might be sufficient for head formation from posterior wounds. In intact animals, wnt expression did not respond to alterations of Hh pathway activity (Sup. Fig. 15), suggesting that Hh control of wnt expression is specific to the establishment of A/P polarity during regeneration.

The expression patterns of hh, ptc, and wnt-P1 did not show a posterior bias as might be expected from their requirement for tail formation (Fig. 3C; Sup. Fig. 16). Whereas such bias could be short-lived or difficult to detect, symmetric Hh activity and wnt expression would require additional components to specifically inhibit β-catenin activity anteriorly. Nonetheless, our data clearly demonstrate synergies between the Hh and Wnt signaling pathways during regeneration. We conclude that Hh influences A/P fate by controlling wnt expression.

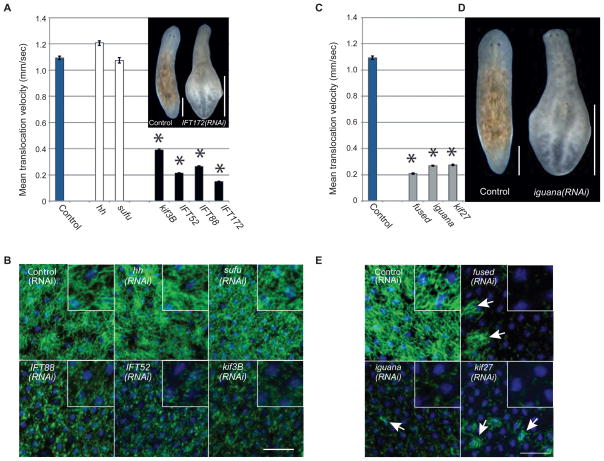

The range of Hh-related regeneration defects from subtle to severe (Fig. 2) provided a sensitive readout to assess whether cilia or other signal transduction components play a role in the planarian Hh pathway. We cloned planarian homologs of intraflagellar transport (IFT) proteins (37) (Smed-IFT52, Smed-IFT88, Smed-IFT172, Smed-kif3b; Sup. Fig. 17), which are universally required for the assembly of cilia (35). Animals fed dsRNA targeting any of the IFT-components lost their cilia-dependent gliding ability, advancing more slowly by waves of whole-body contraction and extension (inchworming) instead (Fig. 4A, Sup. Fig. 18, Sup. Movie 3). Consistently, their cilia were severely shortened (Fig. 4B). Additionally, IFT(RNAi) animals developed edema (inset Fig. 4A), likely due to impaired osmoregulation by their heavily ciliated protonephridia. Targeting Hh pathway components did not affect cilia (Fig. 4A,B). Despite the prominent cilia defects, IFT(RNAi)-treated animals showed no evidence of altered Hh signaling during regeneration by morphology and early marker expression (Sup. Fig. 19), and ptc expression was unaffected in the CNS, pharynx, and gut (Sup. Fig. 20A). Although we cannot entirely exclude subtle, non-regeneration related, or residual cilia contributions (17), our data did not uncover a role for cilia in planarian Hh signaling.

Fig. 4.

Hh signaling is cilia-independent and kif27, fused, and iguana are cilia genes in planarians. (A) Mean translocation speed quantified from movies of animals having received the indicated RNAi-treatments. Error bars: SEM. Asterisks: p-value < 0.01 vs. control (One-way ANOVA). ≥ 4 movies with N ≥ 5 animals per movie. Inset: Example of tissue edema caused by IFT172(RNAi). Scale bar, 0.5 mm. (B) Ventral cilia confocal projections (green, anti-acetylated Tubulin), overlayed with nuclei (blue, DAPI) to demonstrate epithelial integrity. RNAi-treatments as indicated. Inset: zoom. Punctate pattern: remaining cilia stumps. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) Translocation speed calculated as in 4A. (D) Tissue edema in iguana(RNAi)-animal 14 days after amputation. Scale bar, 0.5 mm. (E) Ventral cilia confocal projections (green, anti-acetylated Tubulin) overlayed with nuclei (blue, DAPI) as in 4B. Arrows: remaining tufts of cilia on cells not yet affected by RNAi. Residual staining in fused(RNAi), iguana(RNAi), and kif27(RNAi) animals due to non-cilia related staining of sub-epithelial structures. Scale bar: 50 μm.

We next cloned the single planarian homologs of Fused (Smed-fused), Cos2/Kif27/Kif7 (Smed-kif27), and Iguana (Smed-iguana) (37) (Sup. Fig. 17), which were all discovered as mutations severely affecting Hh signaling in Drosophila (4, 5) or zebrafish (18, 19), respectively. Silencing fused, kif27, or iguana neither perturbed ptc expression (Sup. Fig. 20B), nor did it elicit Hh-related regeneration defects (Sup. Fig. 21). Hence these components are unlikely to function in planarian Hh signaling, but the same caveat raised for the IFT genes applies. Intriguingly, fused(RNAi), kif27(RNAi), or iguana(RNAi)-treated worms instead displayed compromised mobility (Fig. 4C), inchworming, tissue edema (Fig. 4D) and complete lack of cilia staining (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, the expression patterns of iguana and kif27 closely resembled those of cilia genes (Sup. Fig. 22). These data demonstrate by multiple functional and morphological criteria, that fused, kif27, and iguana are essential for planarian ciliogenesis.

This finding establishes that the ciliogenesis functions of Fused, Kif7, and Iguana are not vertebrate-specific (15, 17), but instead ancestral. The use of cilia, Fused, Kif7, and Iguana in the zebrafish Hh pathway (13–15, 18, 19 ), cilia and Kif7 in the mouse Hh pathway (8–10), and Fused and Cos2 in the Drosophila Hh pathway (3) further implies that all three model organisms rely on cilia and/or ancient cilia components for Hh signaling. Thus, the association between Hh signaling and cilia is most likely also ancestral (Sup. Fig. 23). This conclusion is based solely on the ciliogenesis functions of Fused, Cos2/Kif27/Kif7, and Iguana and is unaffected by whether they also function in planarian Hh signaling. In fact, uncovering evidence to this effect would further strengthen the argument for an ancestral connection.

Our findings suggest that the perplexing diversity in Hh signal transduction mechanisms among flies, fish, and mammals arose from group-specific losses of the ancestral association between cilia and Hh signaling (Sup. Fig. 23). This raises the question why core components are highly conserved, yet the contribution of cilia-related proteins to Hh signaling is variable. The dynamic shuttling of core components between subcellular compartments in both flies and vertebrates (9, 10, 36) may have originally been organized by cilia (providing a location) and the associated IFT complexes (providing the motors). The divergence of Hh signaling mechanisms could thus reflect the choice of a new location or motor for organizing the interplay between core components.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Ingham PW, Placzek M. Nature reviews. 2006 Nov;7:841. doi: 10.1038/nrg1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lum L, Beachy PA. Science. 2004 Jun 18;304:1755. doi: 10.1126/science.1098020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Development. 2006 Jan;133:3. doi: 10.1242/dev.02169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisson JC, Ho KS, Suyama K, Scott MP. Cell. 1997 Jul 25;90:235. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preat T, et al. Nature. 1990 Sep 6;347:87. doi: 10.1038/347087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Aug 9;102:11325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huangfu D, et al. Nature. 2003 Nov 6;426:83. doi: 10.1038/nature02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung HO, et al. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endoh-Yamagami S, et al. Curr Biol. 2009 Aug 11;19:1320. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liem K, Jr, He M, Ocbina P, Anderson K. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Aug 11;106:13377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen MH, Gao N, Kawakami T, Chuang PT. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Aug;25:7042. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7042-7053.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchant M, et al. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Aug;25:7054. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7054-7068.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tay SY, Ingham PW, Roy S. Development. 2005 Feb;132:625. doi: 10.1242/dev.01606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff C, Roy S, Ingham PW. Curr Biol. 2003 Jul 15;13:1169. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00461-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson CW, et al. Nature. 2009 May 7;459:98. doi: 10.1038/nature07883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aanstad P, et al. Curr Biol. 2009 Jun 23;19:1034. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang P, Schier AF. Development. 2009 Sep;136:3089. doi: 10.1242/dev.041343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekimizu K, et al. Development. 2004 Jun;131:2521. doi: 10.1242/dev.01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolff C, et al. Genes & development. 2004 Jul 1;18:1565. doi: 10.1101/gad.296004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burglin TR, Kuwabara PE. WormBook. 2006;1 doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.76.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodrich LV, Johnson RL, Milenkovic L, McMahon JA, Scott MP. Genes & development. 1996 Feb 1;10:301. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Struhl G. Cell. 1996 Nov 1;87:553. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81374-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marigo V, Scott MP, Johnson RL, Goodrich LV, Tabin CJ. Development. 1996 Apr;122:1225. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang D, et al. Development. 2003 Apr;130:1645. doi: 10.1242/dev.00395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonnet F, Deutsch J, Queinnec E. Dev Genes Evol. 2004 Nov;214:537. doi: 10.1007/s00427-004-0435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takashima S, Mkrtchyan M, Younossi-Hartenstein A, Merriam JR, Hartenstein V. Nature. 2008 Jul 31;454:651. doi: 10.1038/nature07156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trowbridge JJ, Scott MP, Bhatia M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Sep 19;103:14134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604568103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingham PW, McMahon AP. Genes & development. 2001 Dec 1;15:3059. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang C, et al. Nature. 1996 Oct 3;383:407. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preat T. Genetics. 1992 Nov;132:725. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.3.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurley KA, Rink JC, Sánchez Alvarado A. Science. 2008 Jan 18;319:323. doi: 10.1126/science.1150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iglesias M, Gomez-Skarmeta JL, Salo E, Adell T. Development. 2008 Apr;135:1215. doi: 10.1242/dev.020289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen CP, Reddien PW. Science. 2008 Jan 18;319:327. doi: 10.1126/science.1149943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adell T, Salo E, Boutros M, Bartscherer K. Development. 2009 Mar;136:905. doi: 10.1242/dev.033761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedersen L, Rosenbaum J. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:23. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong SY, Reiter JF. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2008;85:225. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acknowledgements: We thank the Sánchez lab for helpful comments and Carrie Adler for sharing data on iguana. Work supported by NIH NIGMS grant RO-1 GM57260 to ASA, and F32GM082016 to KAG. JCR was funded by the European Molecular Biology Association. ASA is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. All sequences associated with this study have been deposited in GenBank and have accession numbers GQ337474 to GQ337490.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.