Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the reported achievements of the 52 first wave total purchasing pilot schemes in 1996-7 and the factors associated with these; and to consider the implications of these findings for the development of the proposed primary care groups.

Design: Face to face interviews with lead general practitioners, project managers, and health authority representatives responsible for each pilot; and analysis of hospital episode statistics.

Setting: England and Scotland for evaluation of pilots; England only for consideration of implications for primary care groups.

Main outcome measures: The ability of total purchasers to achieve their own objectives and their ability specifically to achieve objectives in the service areas beyond fundholding included in total purchasing.

Results: The level of achievement between pilots varied widely. Achievement was more likely to be reported in primary than in secondary care. Reported achievements in reducing length of stay and emergency admissions were corroborated by analysis of hospital episode statistics. Single practice and small multipractice pilots were more likely than large multipractice projects to report achieving their objectives. Achievements were also associated with higher direct management costs per head and the ability to undertake independent contracting. Large multipractice pilots required considerable organisational development before progress could be made.

Conclusion: The ability to create effective commissioning organisations the size of the proposed primary care groups should not be underestimated. To be effective commissioners, these care groups will need to invest heavily in their organisational development and in the short term are likely to need an additional development budget rather than the reduction in spending on NHS management that is planned by the government.

Key messages

The level of reported achievement between the total purchasing pilots in 1996-7 varied widely; achievement was more likely to occur in primary than in secondary care

Single practice and small multipractice pilots were more likely than large multipractice pilots to report achieving their objectives in 1996/97; achievements were also associated with higher direct management costs per head

Large multipractice pilots needed more time for organisational development before progress could be made

Difficulties in creating effective commissioning organisations the size of the proposed primary care groups should not be underestimated

Primary care groups will need to invest heavily in organisational development and are likely to need an additional development budget in the short term

Introduction

The NHS Executive’s initiative on total purchasing provided an opportunity for volunteer fundholding general practices throughout Britain to receive a delegated budget from their local health authority to purchase potentially all the hospital and community health services for their patients.1 We examined the factors contributing to the different levels of reported achievement among the first wave of these total purchasing pilot schemes—that is, in England and Scotland—in their first “live” year, 1996-7. We then explored the implications of the findings for the development of similar pilots proposed by the government for England—primary care groups.2

The pilots varied greatly in size, organisation, and ambition.3 As there was no detailed blueprint for total purchasing, the pilots interpreted the concept in different ways and developed their scheme at different rates. As a result, several distinct types of pilot emerged (table 1):

Table 1.

Levels of reported achievement and selected characteristics of 52 total purchasing pilots, 1996-7. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Level of achievement and characteristics | Type of pilot*

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undeveloped (n=2) | Developmental (n=11) | Copurchaser (n=8) | Primary care developer (n=8) | Commissioner (n=23) | |

| Level of reported achievement† in pilot’s own terms: | |||||

| Low | 2 (100) | 8 (73) | 3 (38) | 2 (25) | 4 (17) |

| Medium | 0 | 2 (18) | 4 (50) | 5 (63) | 6 (26) |

| High | 0 | 1 (9) | 1 (13) | 1 (13) | 13 (57) |

| Level of reported achievement† in services related to total purchasing: | |||||

| Low | 2 (100) | 11 (100) | 7 (88) | 6 (75) | 6 (26) |

| Medium | 0 | 0 | 1 (13) | 2 (25) | 6 (26) |

| High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (48) |

| Size of pilot: | |||||

| Median No of practices | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Median No of practitioners | 17 | 23 | 13 | 16 | 13 |

| Median population | 32 689 | 36 590 | 24 750 | 27 500 | 25 000 |

| Organisational structure: | |||||

| Complex | 1 (50) | 6 (55) | 2 (25) | 2 (25) | 9 (39) |

| Intermediate | 1 (50) | 3 (27) | 4 (50) | 3 (38) | 6 (26) |

| Simple | 0 | 2 (18) | 2 (25) | 3 (38) | 8 (35) |

| Median cost of direct management per patient (£) | 0.91 | 2.86 | 1.61 | 2.80 | 3.10 |

See Introduction for definitions of the five types. †Low achievement comprises groups 1 and 2; medium achievement, group 3; and high achievement, groups 4 and 5. See Methods for further clarification.

Commissioners—the predominant type of pilot, characterised by holding a delegated budget and directly purchasing care;

Copurchasers—did not hold a budget but worked in partnership with their health authority to influence its commissioning;

Primary care developers—focused purely on primary care development;

Developmental pilots—used the first live year as a further preparatory period;

Undeveloped pilots—did not aim to achieve any change in services.

Methods

The diversity in approaches, combined with the fact that many objectives of the pilots were not directly quantifiable (for example, to improve interagency relations), meant that evaluation of achievement was necessarily limited to assessment of self reported progress.4 Two assessments were made: firstly, the achievement of objectives in the pilot’s own terms—that is, regardless of scope—and secondly, achievements in service areas related to total purchasing. The latter assessment concerned achievements exclusively in services that total purchasers had the power to purchase for the first time: maternity services; services for seriously mentally ill patients; care of frail elderly patients in the community; accident and emergency services; emergency medical inpatient services; and the development of alternatives to acute hospital inpatient services.

There were 52 first wave pilots (46 in England, 6 in Scotland). In autumn 1995 (midway through the pilots’ preparatory year) and in spring 1997 (at the end of the first live year) we conducted face to face, semistructured interviews with a lead general practitioner, project manager, and local health authority manager responsible for liaison in each project. In 1997 we asked each respondent whether the pilot had achieved its four main objectives derived from purchasing intentions documents and from the interviews in 1995. Recognising the subjective nature of the responses, and the need to reduce potential bias, we considered an objective to have been achieved only if there was agreement between all the three respondents. Moreover, where such achievements affected trusts, further corroboration was sought from provider representatives and, where relevant, hospital activity data.

Three researchers independently assigned each pilot to one of five hierarchical groups on the basis of its number of self reported achievements. For achievements in the pilot’s own terms, a “group 1” pilot was one that had reported not having achieved any of its objectives in 1996-7, whereas a “group 5” pilot had reported achieving all four of its objectives. For achievements in services related to total purchasing, a group 1 pilot was one that had not influenced services in any area related to total purchasing, whereas a group 5 pilot had influenced at least three or four of these services. The grouping of pilots also took account of achievements of objectives that had emerged after the 1995 interviews. If the researchers’ groupings differed, a consensus decision was reached through discussion.

Results

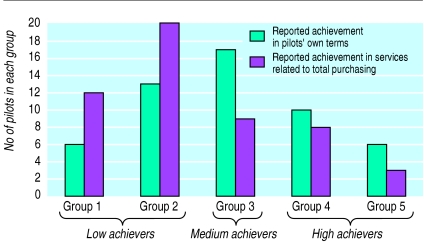

The figure shows the distribution of achievement reported by the total purchasing pilots in 1996-7. It shows a wide variation in the abilities of the pilots to meet their own objectives, suggesting that most had overestimated what they could achieve in the first year. For areas related to total purchasing, there was a shift towards the lower groupings, indicating that such objectives were more difficult to achieve and that a proportion of achievements in the pilot’s own terms were in service areas already included in fundholding.

Table 2 shows that about half the purchasing objectives were reported to have been met (with rates varying from 39% in mental health to 87% of objectives related to extending the primary healthcare team). That the lowest rate of achievement was in mental health is scarcely surprising given the complexity of purchasing and service development in this field. In the acute sector, pilots found it easier to meet objectives relating to early discharge than to reduce emergency admissions. Moreover, objectives were more easily achieved in primary than in secondary care. The pilots wishing to influence mental health care, for example, found making changes in inpatient services that were controlled by mental health trusts more difficult than extending existing primary care services through, for example, the development of community psychiatric nursing.

Table 2.

Achievements of 52 total purchasing pilots by service area, 1996-7

| Service area of four main purchasing objectives | No of pilots with objectives | No (%) of pilots reporting objective achieved |

|---|---|---|

| Early discharge/reducing length of stay | 22 | 14 (64) |

| Community and continuing care | 19 | 10 (53) |

| Maternity services | 27 | 14 (52) |

| Reducing emergency admissions | 32 | 14 (44) |

| Mental health services | 28 | 11 (39) |

| Developing the primary healthcare team | 15 | 13 (87) |

| Improving information/population needs assessment | 12 | 10 (83) |

| Other* | 35 | 21 (60) |

A wide variety, including oncology, cardiology, school health, and palliative care.

Hospital episode statistics were analysed to corroborate self reported achievements for the pilots that were trying to reduce emergency admissions and lengths of stay (table 3). This analysis showed a high level of consistency between the achievements reported by the pilots and the activity changes seen in the hospital episode statistics. Table 3 shows that the hospital episode statistics corroborated the reported success in reducing length of stay in 13 of the 16 commissioner and copurchaser pilots. The other three pilots had implemented their expressed mechanism for change, but the hospital episode statistics did not show reduced average length of stay. Similar findings from the data analysis corroborate the reported achievements in influencing emergency admissions (unpublished data).

Table 3.

Level of agreement, by type of pilot, between total purchasing pilots’ own reporting on whether they achieved their objectives to reduce length of stay and emergency admissions, and hospital episode statistics on activity levels*

| Objective | Pilot reported “achieved”

|

Pilot reported “not achieved”

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed by hospital episode statistics?

|

Data not available | Total | Confirmed by hospital episode statistics?

|

Data not available | Total | ||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| To reduce hospital length of stay: | |||||||||||

| Commissioners | 8 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Copurchasers | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| To reduce emergency admissions: | |||||||||||

| Commissioners | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 8 | |||

| Copurchasers | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||

Full details of the methods and results of this analysis are available from the authors.

Levels of reported achievement seemed to be associated with type of pilot (table 1). Commissioner pilots tended to be the highest “achievers” in their own terms and were the only type that reported achieving all of their main objectives in services related to total purchasing. In comparison, copurchasers and primary care developers were most often medium achievers in their own terms, and most had had little or no impact on services related to total purchasing. Most developmental and all undeveloped pilots were low achievers.

Two other characteristics were associated with level of achievement3:

• • Smaller pilots (those with fewer practitioners and smaller populations) were more likely than larger ones to report achieving their objectives; none of the large multipractice pilots with six practices or more was a high achiever (groups 4 or 5)

• • Larger pilots had to establish complex organisations before they could make progress, whereas smaller, particularly single practice pilots, achieved their objectives with little organisational development.

The pilots with the highest direct management costs per head were the most likely schemes to meet their objectives. As the level of management spending was a matter of negotiation between each pilot and its parent health authority, the level allocated by the health authority might have been an indication of the confidence it placed in the ability of the pilot to bring about beneficial change.

Discussion

The New NHS white paper sets out the government’s intention to establish primary care groups in England by April 1999.2 All primary care groups will have a budget covering general practitioner prescribing and practice infrastructure. As the groups develop, they will take responsibility for a greater share of hospital and community health services resources and, in the latter stages, the General Medical Services budget. Primary care groups, designed to comprise “natural communities” of about 100 000 patients, should “grow out” of the range of existing general practitioner-led commissioning schemes in the NHS. Most total purchasing pilots in England are likely, therefore, to become integrated into these larger organisations.

It is encouraging that primary care groups will be able to hold delegated budgets as we found a clear relation between first year achievements in areas related to total purchasing, and commissioner pilots. In particular, the early success of commissioner pilots in reducing length of stay shows that primary care based budget holding with independent contracting has the potential to assist in the management of demand for expensive hospital facilities. In contrast, pilots trying to influence service changes without holding a budget made far less progress in the first year.

Organisational development needs

That the largest total purchasers achieved the least in 1996-7 suggests that primary care groups (which are likely to be almost three times as large) will require considerable time to develop organisationally before effective progress can be made. Multipractice pilots that reported the highest level of achievement had developed structurally complex organisations, employed a dedicated project manager, developed reasonable or good relations with their local health authority, had regular discussions with local providers, invested in information technology, encouraged the involvement of non-lead general practitioners, and ensured participation from all the practices within the group.3 The low achieving multipractice pilots were characterised by poorly developed organisations (in particular, lacking a project manager).

The organisational development of primary care groups is likely to prove even more challenging because (a) primary care groups will comprise not just volunteer fundholding practices but all practices in a given area, including non-fundholders and some practices with little experience of commissioning services; (b) the requirement that community nurses should be involved in managing primary care groups is likely to add to the complexity of the developmental task; and (c) most total purchasers rely on a very limited number of motivated and skilled individuals—acquiring enough input from general practitioners and skilled management support to run 500 primary care groups effectively will be demanding.

Funding primary care groups

A final implication for primary care groups relates to the amount of funding. Most of the highest achieving multipractice pilots were in the top quarter for direct management costs. These pilots tended to pay for general practitioner locums and additional hours for general practitioners. In some cases they made a further allowance to each practice for staff participation in project development, and they all invested heavily in information systems.5 Yet the government aims to reduce the total costs of running health authorities and primary care based commissioning by £200m each year for five years. In the short term, however, costs are likely to rise as health authorities will have to operate as the main purchaser until all the local care groups are fully established. In the longer term it is possible that management costs can be contained, but other evidence from the current national evaluation project indicates that it would be unwise to assume that primary care groups are necessarily a cheaper alternative to the status quo.5

The experience of the total purchasing pilots suggests that the organisational task in creating primary care groups should not be underestimated. In particular, engendering collective responsibility among all practitioners for staying within budget or adhering to prescribing and referral protocols, or doing both of these, proved difficult in the pilots, in which participation was voluntary.3 In primary care groups—in which participation will be compulsory—a collective approach will take time to achieve as most groups are likely to include practitioners antagonistic to the concept, as it implies a reduction in individual autonomy and a greater emphasis on rationing. Primary care groups will also need to address the issue of sustainable management as the evidence suggests that total purchasing was typically run by a few individuals with high workloads.3 The development of commissioning-style primary care groups is therefore likely to be slow in most cases.

However, primary care groups will operate not as pilots with a fixed life span but as the centre piece of the “new NHS” at local level. They will thus be able to call on the unambiguous support of their local health authorities, and trusts will have to recognise their standing. The concession for primary care groups to operate at a range of different levels, at least initially, is also appropriate and necessary as the volunteer total purchasing pilots developed at different speeds. Similarly, the government’s intention that all care groups should ultimately move towards the commissioning-style model is supported by the experience of the pilots in relation to total purchasing.

Data are being collected on the second live year of total purchasing (1997-8); these will show whether the largest projects have managed to “catch up” in terms of overall achievement. If so, the evaluation will provide important lessons for the developmental needs of successful, large scale commissioning groups (such as primary care groups); if not, it will question the feasibility and desirability of primary care led commissioning at the larger scale proposed in the white paper.

Figure.

Distribution of total purchasing pilots by level of achievement (groups 1 to 5) in relation to objectives in pilots’ own terms and to services related to total purchasing, 1996-7

Acknowledgments

The national evaluation of total purchasing is a collective effort by a consortium of health services researchers led from the King’s Fund. Staff come from the National Primary Care Research and Development Centre at Manchester, Salford, and York Universities; the Universities of Bristol, Edinburgh, and Southampton; the Health Services Management Centre at the University of Birmingham; and the Health Services Research Unit at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the two funding departments.

Footnotes

Funding: Department of Health and the Scottish Office Health Department.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Mays N, Goodwin N, Bevan G, Wyke S.on behalf of the Total Purchasing National Evaluation Team. What is total purchasing? BMJ 1997315652–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Secretary of State for Health. The new NHS. London: Stationery Office; 1997. (Cm 3807.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mays N, Goodwin N, Killoran A, Malbon G.on behalf of the Total Purchasing National Evaluation Team. Total purchasing: a step towards primary care groups. 1998London: King’s Fund [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahon A, Leese B, Baxter K, Goodwin N, Scott J. Developing success criteria for total purchasing pilot projects. London: King’s Fund; 1998. (Working paper on the national evaluation of total purchasing pilot projects.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posnett J, Goodwin N, Griffiths J, Killoran A, Malbon G, Mays N. The transaction costs of total purchasing. London: King’s Fund; 1998. (Working paper on the national evaluation of total purchasing pilot projects.) [Google Scholar]