Abstract

With the exception of HIV care, informal caregiving of chronically ill lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults has received very limited attention in the extensive caregiving literature. This article reports on research that considered the social context of care and a dyadic caregiving approach for 36 chronically ill LGB adults ages 50 and older and their informal caregivers. In this study, both discrimination and relationship quality were associated with depression among chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. Furthermore, preliminary findings suggested that relationship quality moderates the impact of discrimination as a risk factor for depression in chronically ill LGB adults. The authors discuss the implications of these findings for social policy and future research. Given the changing demographics in the United States with the aging of the baby boomers, as well as an increase in chronic illness, fostering better understanding of caregiving across diverse sexualities and families is critical.

Keywords: elder, caregiving, depression, social policy, LGB older adults

The current social and political context in the United States, which includes an ever-growing population of older adults, ongoing discussions about the widespread legalization of same-sex marriage and parenting, and differential treatment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults under the law, combines with longstanding cultural values of individualism and family care of elders to form the backdrop for caregiving in this country. The majority of care for U.S. adults with chronic (long-term) illnesses is provided not in nursing homes or other formal care organizations, but informally at no public cost (Stone, 2000). Families and friends provide 70% to 80% of the informal in-home care for adults with chronic illnesses. An estimated 21% of the U.S. population provides unpaid care to family and friends age 18 or older, which translates into more than 44 million informal caregivers (National Alliance for Family Caregiving & AARP, 2004).

Chronic illness can occur at any age, but the incidence of chronic conditions increases in midlife and continues into old age (Barker, Herdt, & DeVries, 2006; Verbrugge, 1989). Chronic illness refers to long-term diseases that have no known cure and are progressive in nature (Royer, 1998). As the population ages, the proportion of people living with chronic illnesses will also increase. By the year 2030, nearly 30% of adults will require assistance and about 20% will have severe limitations with high needs, placing increased demands on informal caregivers (Stone, 2000). As of 2005, 12% of the U.S. population was age 65 or older. This percentage is expected to increase dramatically through 2050, when people ages 65-plus are expected to comprise 21% of the population. Moreover, adults ages 80 and older constituted 4% of the U.S. population in 2005 and are expected to comprise 8% of the population by 2050 (Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2006).

Economically, the current system of care relies on informal, unpaid support from family, friends, and community members. That is, without the system of informal support, long-term care costs of older adults would more than double, according to recent estimates. For example, the total cost of publicly funded eldercare is projected to grow from 38% of total health care costs in the year 2000 to nearly 75% when the population of adults over age 65 doubles by the year 2030 (Evashwick, 2001; Feinberg, 2001). Whereas most research on caregiving has targeted caregivers helping those 65 years of age and older, about 40% of adults with disabilities are younger than 65. The United States General Accounting Office (1995) has estimated that about 5 million adults ages 18–64, the majority of whom live in the community, require assistance with day-to-day activities.

Informal caregiving is defined as unpaid assistance, provided primarily by family members and friends, that helps ill and disabled adults remain in the community (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2007a). Policy changes have placed increased responsibility on informal caregivers to provide ongoing assistance to ill and disabled family members and friends. Current state and federal pressure to reduce health care costs, including managed care, hospital downsizing, and Medicaid cuts, have increased demands on caregivers. Extensive family caregiving is not a new phenomenon, but today's informal caregiving is more technologically demanding, of longer duration, and more often for multiple individuals in need of care (Bengston, 2001).

Although salutary consequences may result from providing care (Clipp, Adinolfi, Forrest, & Bennett, 1995), many caregivers experience serious physical and mental distress (Lyons, Sayer, Archbold, Hornbrook, & Stewart, 2007; Polen & Green, 2001). Existing literature (Lyons, Zarit, Sayer, & Whitlatch, 2002; Whitlatch, 2008) has pointed to the need to consider variations in care experiences and outcomes both for those receiving care and for their informal caregivers—although most research has focused primarily on the caregiver and has paid limited attention to the person receiving care or to the caregiving relationship. Failure to consider the caregiving relationship not only excludes care receivers as active participants in the caregiving process and their caregiving outcomes but also diminishes the exploration of alternate caregiving structures.

Family Care

Families in the United States are undergoing dramatic changes and are becoming increasingly heterogeneous due to growing numbers of individuals living alone, single-parent households, and diverse family structures (U.S. Census Bureau, 1996, 2003). The number of unmarried cohabiting couples also has increased substantially in recent years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). Despite problems related to underreporting, the 2000 U.S. census counted approximately 595,000 same-sex unmarried households (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003), which represents an increase from the 145,000 such households identified in the 1990 census (U.S. Census Bureau, 1990).

With the exception of HIV-related care, informal care among sexual minorities has received very limited attention in the extensive research on caregiving. HIV caregiving has been linked repeatedly to elevated levels of caregiver burden and distress (Callery, 2000; Wight, 2000, 2002; Wight, LeBlanc, & Aneshenesel, 1998), with both alienation and stigma associated with increased distress among caregivers (Wight, 2000). More recently, a study of caregiving dyads (Wight, 2007) found that future uncertainty was positively associated with depression among individuals living with HIV. Moreover, the caregivers' sense of future uncertainty was associated with the care recipients' depressive symptoms. Based on a conceptual model of resilience, Fredriksen-Goldsen (2007b) found that well-being among HIV caregivers was significantly associated with better caregiver health, higher income, and more dispositional optimism and self-empowerment, as well as lower levels of discrimination and multiple loss.

Aside from HIV care, existing caregiving research largely has overlooked diverse sexualities and families, perhaps reflecting deeply embedded assumptions about the primacy of biological family members in providing care. Yet, the older LGB population is projected to grow from approximately 2 million to more than 6 million by the year 2030 (Berger, 1996; Cahill, South, & Spade, 2000). Research has suggested that lesbians and gay men have extensive caregiving responsibilities. For example, an early study (Fredriksen, 1999) found that 32% of lesbian and gay male adults had informal caregiving responsibilities, including caring for children, disabled working-age adults, and elders; of those, 8% were caring for elders. Among lesbian and gay male individuals ages 50 and older in a large New York City study (Cantor, Brennan, & Shippy, 2004), 8% reported a current need for caregiving assistance, whereas 19% had needed care in the past.

Partners and friends most often provide care to those in need in LGB communities, in part due to lack of availability of biological family members and sensitive care providers (Cantor et al., 2004; Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2007a; Grossman, D'Augelli, & Dragowski, 2007). The majority of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals ages 50 and older have reported that they would turn to their partners first for caregiving support; among those without partners, most would seek help from friends (Cahill, Ellen, & Tobias, 2003; Cantor et al., 2004). A recent national survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender baby boomers (MetLife Mature Market Institute, Lesbian and Gay Aging Issues Network of the American Society on Aging, & Zogby International, 2006) found that one quarter were providing caregiving assistance; an alarming statistic was that one out of five were unsure of who would be available when they themselves needed care.

Because of their history of marginalization and invisibility, chronically ill lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and their caregivers may encounter obstacles in receiving and providing care, including discrimination in health and human services, lack of traditional sources of support, limited access to supportive services, and lack of legal protection for their loved ones (Barker et al., 2006; Brotman, Ryan, & Cormier, 2003; Cahill et al., 2000; Clunis, Fredriksen-Goldsen, Freeman, & Nystrom, 2005; Fredriksen, 1996, 1999; Gabbay & Wahler, 2002; Hash, 2001; Hash & Cramer, 2003). Several studies (Herek, Chopp, & Strohl, 2007; Meyer & Northridge, 2007) have suggested that the prejudice and discrimination sexual minorities experience has deleterious effects on their physical and mental health. Thus, chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers also may be at especially high risk for discrimination, as well as negative physical and mental health outcomes.

A recent qualitative study of caregiving (Brotman, Ryan, Collins, Chamberland, Cormier, & Julien, 2007) found that discrimination was salient in the lives of gay and lesbian elders and their caregivers. Understanding the relational aspect of the caregiving relationship as potentially protective may be especially important within marginalized communities, where greater reliance on informal supports is often favored over formal services. The extent to which the caregiving relationship itself may mitigate the effects of discrimination and ease psychological distress for chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers has not been fully examined to date.

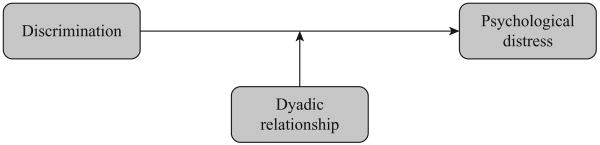

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of chronically ill LGB adults ages 50 and older and their informal caregivers. First, we will describe the background characteristics, types of care relationships and responsibilities, and caregiving outcomes among both members of the caregiving dyad. As part of this study, we also conducted preliminary analyses of the relationship between discrimination, relationship quality, and psychological depression. (See Figure 1 for the proposed model.) Last, we will discuss the potential implications of these findings for public policies and future research.

Figure 1. Proposed model of discrimination, dyadic relationship quality, and psychological distress.

A more complete understanding of caregiving among chronically ill LGB adults will increase understanding of an important relational dimension within diverse family constellations and sexualities. Furthermore, the social context of care is most often absent in the general caregiving literature, but is particularly salient when studying caregiving within marginalized communities. The insights gleaned from the study of caregiving within these populations can deepen understanding of the richness and diversity of people's lives, relationships, and sexualities. Such information is central to developing research, services, and public policies to support the increasing diversity in U.S. society.

Method

The sample comprised 36 pairs of chronically ill LGB adults ages 50 and older and their adult caregivers (N = 72 individuals) living in an urban environment in the Pacific Northwest. The care recipients in the study reported having a chronic illness, were currently receiving caregiving assistance, were cognitively able to participate, and self-identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual. The primary caregiver, who could be of any sexual orientation, was defined as the person the chronically ill adult had designated to assist most with daily needs, a person who was neither paid nor working as a volunteer affiliated with a service organization. Only primary informal caregivers and their care recipients participated in the study.

In the recruitment phase of the research, we contacted potential participants via announcements posted at various health, human service, and community-based organizations (e.g., health clinics, support groups, buddy programs, community-based churches and social groups), as well as in community-based newspapers and newsletters. Compared with relying on a sample drawn solely from one site, such as a support group or a health clinic, recruiting from a number of sites minimized biases.

We conducted face-to-face interviews with participating chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers at a time and location of their choice where privacy could be ensured. The members of the caregiving dyads were interviewed simultaneously in separate rooms for 75 to 90 minutes. Interviewers were trained in the social and behavioral sciences, had experience working with LGB populations, and were knowledgeable about methods and techniques for effective interviewing of adults with functional disabilities and their caregivers.

Theoretically relevant variables were assessed for both the chronically ill LGB adults and the caregivers in this study. The following sociodemographic variables were measured in standard formats: age, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, income, education, living arrangement, health status, types of chronic illness, and relationship status. We also obtained information on the extent of care provided and the type of advanced legal planning care recipients had completed.

Discrimination was measured by how often the respondent felt discriminated against on the basis of six domains: sexual orientation, race or ethnicity, gender, gender identity, ability status, and age. The six questions were scored on a scale of 0 (none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time) and summed across categories (Cronbach's alpha: care recipients = .80; caregivers = .73).

Dyadic relationship quality, an 11-item measure, was based on items from the McMaster Family Assessment Device relationship quality scale (Baronet, 2003; Epstein, Baldwin, & Bishop, 1983), which assesses the quality of relationships with respect to mutual understanding, closeness, and acceptance. We adjusted the items in the scale to a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 4; the lower score indicates low level of relationship quality) and calculated a mean score across the items (Cronbach's alpha: care recipients = .92; caregivers = .84).

We measured depression using the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item measure of depressive symptoms experienced during the past week. We measured the 20 items on a scale of 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (all of the time) and summed across the items. A score of 16 to 26 is often considered to reflect minor depression; a score of 27 or higher is often considered to indicate major depression (Ensel, 1986; Zich, Attkisson, & Greenfield, 1990). Used extensively in caregiving research (Aneshensel, Pearlin, Mullan, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 1995; Gerstel & Gallagher, 1993) with a variety of populations, the CES-D demonstrates good convergent and discriminate validity. In addition, the instrument has moderate test-retest reliability (r = .31 to r = .54) and good concurrent validity with a variety of other depression measures. In this study, the measure demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha: care recipients = .92; caregivers = .84).

Data Analysis

In the initial stages of data analysis, we examined distributions on key variables and computed proportions (if indicated), means, and standard deviations for each variable. We examined distributions of the scale scores and computed measures of internal consistency for each scale using Cronbach's alpha. Descriptive statistics were used to examine sociodemographic characteristics, relationship status, discrimination, relationship quality, and psychological distress among chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers.

Prior to conducting preliminary bivariate analyses, we first explored whether the depression of one dyad member was affected by the other dyad member's perceived discrimination or perceived relationship quality. We used preliminary multi-level modeling (MLM) in order to examine the partner effect, as Kenny, Kashy, & Cook (2006) have suggested. The MLM analysis found that one partner's depression was not affected by the other's perceived social discrimination (b = .148, t[50] = .429, p = .670); neither was it influenced by the level of the other's dyadic relationship quality (b = .259, t[42] = .083, p = .935). Because partner effects were not detected, we conducted the remaining analyses separately for the chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers.

Next, we completed preliminary bivariate regressions to assess whether direct associations of depression were present with social discrimination, dyadic relationship quality, and relationship status for chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. We examined regression coefficients of the bivariate regressions on discrimination and relationship quality with one-tailed t-test because the proposed relationships were directional. Last, if direct associations were found, we explored whether dyadic relationship quality seemed to moderate the correlation between discrimination and depression by using a moderated multiple regression. To this end, we generated two preliminary regression models as Baron and Kenny (1986) have suggested. The first model (Model 1) included discrimination and dyadic relationship quality; we added an interaction term in the second regression model (Model 2). The two independent variables were standardized before entry to alleviate the potential threat of multicollinearity. In order to explore the possible nature of the moderator effect, we conducted two separate regression analyses, for both high and low level of dyadic relationship quality.

Findings

Background Characteristics

The chronically ill LGB adults in this study were 50 years of age and older; their ages were distributed as follows: 80%, 50–59 years of age; 11%, 60–69; and 9%, age 70 or older. Of those receiving care, 58% were male and 42% were female. In terms of race and ethnicity, 51% of the LGB care recipients were White, 20% African American, 9% Hispanic, and 3% Native American. Nearly 70% reported household incomes of less than $20,000. Care recipients' most common chronic illnesses were arthritis (58%), HIV (44%), high blood pressure (42%), heart condition (36%), chronic lung disease (28%), and diabetes (19%). The majority of chronically ill LGB adults in this sample did not have a will (53%) or a durable power of attorney for health care (56%). Table 1 displays the background characteristics of those receiving care and their caregivers.

Table 1. Background Characteristics of Chronically Ill Midlife and Older LGB Care Recipients and Caregivers.

| Care recipient | Caregiver | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 50 | 0 | 69.4% |

| 50–59 | 80.0% | 19.5% |

| 60–69 | 11.4% | 8.3% |

| 70 and older | 8.6% | 2.8% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 58.3% | 69.4% |

| Female | 41.7% | 30.6% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 51.4% | 50.0% |

| African American | 20.0% | 30.6% |

| Hispanic | 8.6% | 0 |

| Asian | 0 | 2.8% |

| American Indian | 2.9% | 2.8% |

| Multiethnic | 17.1% | 13.8% |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay or lesbian | 66.7% | 60.0% |

| Bisexual | 33.3% | 17.1% |

| Heterosexual | 0 | 20.0% |

| Other | 0 | 2.9% |

| Partner status or marital status | ||

| Partnered or married | 55.6% | 55.6% |

| Single | 19.4% | 33.3% |

| Divorced or separated | 11.1% | 8.3% |

| Widowed | 13.9% | 2.8% |

| Income | ||

| < $20,000 | 68.6% | 51.4% |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 11.4% | 17.1% |

| $40,000–$59,999 | 11.4% | 22.9% |

| $60,000 or more | 8.6% | 8.6% |

| Caregiving relationship status | ||

| Partner or spouse | — | 50.0% |

| Friend | — | 47.2% |

| Biological family | — | 2.8% |

| Advance legal planning | ||

| Will | 47.2% | 40.0% |

| Health care power of attorney | 50.0% | 37.1% |

Whereas all of the adults receiving care self-identified as lesbian, gay male, or bisexual, 20% of the caregivers were heterosexual. Almost half of the caregivers were 40–49 years of age (25% were younger than 40). The distribution of the caregivers' ages was as follows: 69% were under age 50, 19% were 50–59 years of age, and 11% were 60 or older. Approximately 70% were male. Of the caregivers, 50% were White, 31% were African American, 3% were Native American, and 3% were Asian. Slightly more than half of the caregivers had an annual household income of less than $20,000. About 60% of the caregivers did not have a will, and 63% did not have a power of attorney for their health care.

The majority of the caregivers provided relatively extensive assistance, with 37% providing 20 or more hours of care per week; 31% provided 10–19 hours of weekly care, 14% provided 5–9 hours, and 17% provided 4 or less hours of care per week. Nearly half of the caregivers provided personal care, such as bathing and dressing; all of the caregivers provided emotional support, 61% provide housekeeping, 58% monitored assistance provided by others, 42% provided direct financial support, and 28% managed financial resources for the care recipient.

In terms of the relationship between the chronically ill LGB adults and their informal caregivers, approximately one half were partners, 47% were friends, and 3% were biological family (most often siblings). The age and gender distributions among care recipients were similar between those receiving care from partners and those receiving care from friends. Most chronically ill LGB African American (86%) adults reported receiving care from friends; among the chronically ill Hispanic participants in the study, all were receiving assistance from their partners. Compared with those in higher income groups, chronically ill participants with lower incomes were more likely to receive care from friends.

Discrimination

In this study, chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers reported experiences of discrimination across all domains. Half of the care recipients reported experiences of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Other types of discrimination they experienced included discrimination based on disability status (58%), age (47%), race or ethnicity (39%), gender identity and expression (29%), and gender (28%). Among caregivers, the most prevalent form of discrimination they experienced was based on sexual orientation (43%), followed by discrimination based on race or ethnicity (32%), disability (29%), gender (26%), gender identity and expression (20%), and age (14%). More than two thirds (69%) of the chronically ill LGB adults and more than half (52%) of their caregivers reported experiencing two or more forms of discrimination. Those receiving care reported discrimination more often (M = 6.89, SD = 4.19) than caregivers (M = 5.31, SD = 3.47), but the difference was not statistically significant (t[35] = 1.94, p = .06). See Table 2 for means, standard deviations, and paired t-tests.

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Paired t-Tests of Key Variables between Chronically Ill Midlife and Older LGB Adults and Caregivers.

| Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | LGB care recipients | Caregivers | t |

| Discrimination | 6.89 (4.19) | 5.31 (3.47) | 1.94 |

| Dyadic relationship quality | 3.30 (0.54) | 3.19 (0.47) | 1.40 |

| Psychological distress | 22.26 (12.51) | 15.06 (8.69) | 2.79** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Dyadic Relationship Quality

In terms of the quality of the dyadic caregiving relationship, care recipients reported a mean score of 3.30 (SD = 0.54) and caregivers reported a mean score of 3.19 (SD = 0.47). Although the chronically ill LGB individuals reported higher levels of relationship quality compared with caregivers, the difference was not statistically significant (t[35] = 1.40, p = .17).

Depression

The level of depressive symptomatology among chronically ill LGB adults (M = 22.26, SD = 12.51) in this study was significantly higher than that of their caregivers (M = 15.06, SD = 8.69), t(35) = 2.79, p < .01. Among the chronically ill participants, more than two thirds reported depressive symptomatology at clinical levels (CESD ≥ 16); 44% had scores indicating major depression (CESD ≥ 27). Of the caregivers, 44% reported scores indicating depressive symptomatology at clinical levels (CESD ≥ 16); 8% reported scores at levels for major depression (CESD ≥ 27).

Relationship Status: Partners Versus Friends

Among this sample, comparing chronically ill adults receiving care from partners with those receiving care from friends, we found no significant differences in care recipients' reported levels of discrimination (partners: M = 6.33, SD = 4.70; friends: M = 7.53, SD = 3.76), dyadic relationship quality (partners: M = 3.49, SD = 0.33; friends: = 3.15, = 0.70), or depression (partners: M = 20.70, SD = 11.79; friends: M = 25.12, SD = 12.55).

Caregivers caring for partners (M = 3.39, SD = 0.35), on the other hand, reported significantly higher levels of relationship quality than those assisting friends (M = 3.03, SD = 0.49; t[33] = −2.53, p < .05). However, we found no significant differences in their reported levels of discrimination (partners: M = 5.78, SD = 3.57; friends: M = 4.78, SD = 3.49) and depression (partners: M = 15.67, SD = 8.38; friends: M = 14.06, SD = 9.32). As Table 3 shows, bivariate regression analyses also suggest that caregiving relationship status is not associated with the level of depressive symptomatology.

Table 3. Bivariate Regression Analyses of Psychological Distress and Discrimination, Dyadic Relationship Quality, and Caregiving Relationship.

| LGB care recipients | Caregivers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Beta | R2 | Beta | R2 |

| Discrimination | .414** | .171 | .337* | .113 |

| Dyadic relationship quality | −.304* | .092 | −.286* | .082 |

| Caregiving relationship | −.184 | .034 | .093 | .009 |

Note. Significant tests of regression coefficients for discrimination and dyadic relationship quality were one-tailed.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Relationship Between Discrimination, Relationship Quality and Depression

Although the sample size in this study did not allow us to test a fully specified model of minority stress (Meyer & Nothridge, 2007) and caregiving (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2007b), we conducted preliminary analyses to begin to explore the relationship between discrimination and relationship quality on depression among chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. In these preliminary analyses, we found that perceived discrimination predicted chronically ill LGB adults' level of depression β = .414, p < .05), an outcome also evident for caregivers (β = .337, p < .05). As Table 3 shows, the higher the degree of perceived discrimination, the higher the level of depressive symptomatology.

Bivariate regression analyses also illustrated that as the degree of dyadic relationship quality increased, the level of depressive symptomatology decreased. The degree of care recipients' perceived dyadic relationship quality was a statistically significant predictor of their level of depressive symptomatology (β = −.304, p < .05, one-tailed). We observed the same pattern for the caregivers in this study; the degree of a caregiver's dyadic relationship quality was a statistically significant predictor of depression (β = −.286, p < .05, one-tailed). As the degree of the dyadic relationship quality increased, the level of depressive symptomatology decreased (see Table 3). In sum, discrimination and dyadic relationship quality emerged as potential key risk and protective factors associated with depression for chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers.

Next, preliminary multiple regression analyses suggested that dyadic relationship quality moderated the relationship between discrimination and depression among chronically ill LGB adults. For those receiving care, the relationship between perceived social discrimination and depression seemed to depend on the level of dyadic relationship quality (β = −.356, p < .05); the main effect of social discrimination remained statistically significant (β = .574, p < .01), but that of dyadic relationship quality did not (β = −.237, p = .117). The preliminary model explained 32% of the variance of depression (see Table 4).

Table 4. Results of Preliminary Multiple Regression Analyses Examining the Moderating Effect of Dyadic Relationship Quality, Beta.

| LGB Care recipients | Caregivers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| (1) Discrimination | .380** | .574** | .308* | .309* |

| (2) Dyadic relationship quality | −.252 | −.237 | −.251 | −.251 |

| (1) × (2) | −.356* | .010 | ||

| R2 | .233** | .323** | .175* | .175* |

| ΔR2 | .090* | .000 | ||

Note. Used one-tailed test for regression coefficients.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

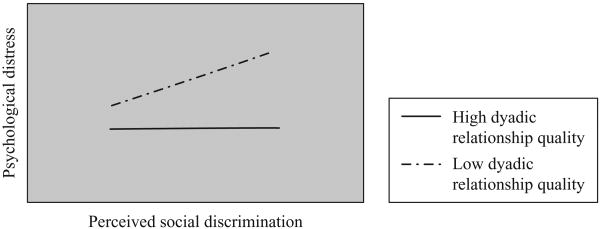

Figure 2 presents the potential nature of the moderating effect of dyadic relationship quality among the chronically ill LGB adults in this study. In Figure 2, two linear lines were generated based on Aiken and West's (1991) recommendations regarding the presentation of an interaction effect of continuous predictors. High and low levels of dyadic relationship quality are represented as one standard deviation above and below the mean. The figure suggests that the level of depression of the low-relationship-quality group increased as the level of discrimination increased. On the other hand, for the high-relationship-quality group, the level of depressive symptomatology changed only slightly as the level of perceived discrimination increased.

Figure 2. Preliminary findings of social discrimination in relation to psychological distress as moderated by dyadic relationship quality for chronically ill midlife and older LGB adults.

Among caregivers, however, we observed no interaction effect on depression between discrimination and dyadic relationship quality (β = .010, p = .951). In the preliminary analysis, controlling for dyadic relationship quality, only the main effect of discrimination on depression was significant (β = .309, p < .05, one-tailed).

Our preliminary findings suggested that both discrimination and dyadic relationship quality may independently account for depression among chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. Even while controlling for dyadic relationship quality and the interaction of the two independent variables, discrimination remained as a main effect on depression for chronically ill LGB adults, as well as their caregivers. As a protective factor, the quality of the dyadic caregiving relationship seemed to moderate the impact of discrimination on depression among those receiving care, but not among caregivers.

Discussion

Given the aging of the U.S. population and the increase in chronic illness in this country, it is crucial to begin to consider and better understand caregiving across diverse families and sexualities. Our research represents one of the first studies to explore the caregiving relationships among chronically ill LGB adults and their informal caregivers. Although the findings are preliminary given the small sample size and the cross-sectional nature of the study, several interesting insights emerging from this study are worthy of further research.

The chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers who participated in this study were an at-risk group, reporting high levels of depressive symptomatology, many at clinical levels for major depression, especially among those with physical impairment. General caregiving research (e.g., George & Gwyther, 1986) has found that caregivers who experience diminished access to support face significantly greater psychological, physical, emotional, social, and financial risks.

Our findings illustrate the importance of understanding the experiences and needs of each member of a caregiving pair and suggest that the caregiving relationship itself may fulfill different functions for chronically ill LGB adults and for their caregivers. Given the impairment of the LGB adults in this study, perhaps they perceived their caregivers as better able to protect them from the negative impacts of discrimination. The similarities and differences in the caregiving experience among those providing and receiving care warrant further study. Such findings underscore the importance of the social context of caregiving, as well as a dyadic approach to caregiving.

In the general caregiving research, women have been found to provide the majority of caregiving assistance (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Scharlach, 2001; Rozario & DeRienzis, 2008), although this situation may differ for HIV care (Turner, Pearlin, & Mullan, 1998) and also differed in our study. The majority of caregiving pairs in this study were of the same sex; when gender differences were present within a pair, men were as likely to be providing care for women as women were to be caring for men. More research is needed to explore the ways in which biological sex, gender roles, and gender identities affect caregiving and care receiving within diverse communities.

Biological family members are generally assumed to form the cadre of available informal caregivers; however, as in earlier studies of the relationships of lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (e.g., Muraco, 2006), friends and chosen family have been shown to play a pivotal role within these communities. In particular, Muraco's research has demonstrated that family ties and expectations of caregiving are present in friendships between lesbians and straight men, as well as in friendships between gay men and straight women. Future research also should explore the role of secondary helpers, helping networks, and teams of partners and friends providing caregiving assistance.

The larger social context is rarely considered in caregiving research. Yet, as we found in our study, discrimination is a key factor in the lives of chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. Both historic and current discrimination targeting chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers seem to manifest in higher levels of psychological distress for both members of the caregiving dyad. Furthermore, chronic strains associated with multiple forms of discrimination may lead to cumulative mental and physical health problems (Meyer & Northridge, 2007; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), such as those reported by the chronically ill adults and caregivers in this study. Stigmatized identities based on sexual orientation, ethnic minority status, disability status, and old age may increase risk (D'Augelli, Grossman, Hershberger, & Connell, 2001; Deevey, 1990), and the combination of multiple oppressed statuses and chronic strains may lead to more physical and mental distress (Meyer & Northridge; Williams et al., 1997).

The findings from our study illustrate the importance of considering the impact of discrimination based on such intersecting stigmatized identities. The frequency with which chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers in this study reported discrimination based on a number of factors (including sexual orientation, physical disability, and impairment) suggest that discrimination and cumulative risk need to be considered in caregiving research across all communities, extending beyond sexual-minority and other marginalized populations. Despite their experiences of discrimination, the majority of those receiving and providing care who participated in our study did not have a will or a durable power of attorney for health care. Without such advance legal planning, chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers remain vulnerable to the negative impacts of social discrimination.

Policy Implications

The findings of our study suggest that discrimination affects chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers and illustrate how the social context can negatively influence the functioning of these potentially vulnerable populations. Although discrimination is part of the social context of care, so are the laws and policies designed to support families and those needing assistance. Most federal and state laws and institutional policies that provide benefits to protect families and support caregiving, such as the federal Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, are generally biased against caregivers and care recipients in same-sex relationships, as well as caregiving among friends. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual caregivers and care recipients are also at risk due to the lack of legal protections against discrimination. In addition, the majority of laws that provide legal protections for caregiving couples—including state-sanctioned marriage statutes, Social Security benefits, and Medicaid spend-downs—exclude those in same-sex relationships.

Family and Medical Leave Act

The federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993 mandates that employers with more than 50 employees must allow employees 12 weeks of unpaid leave during a 12-month period to care for ill family members. Employers must continue health care coverage during leave periods and ensure that employees can keep their jobs or receive equivalent positions upon return. Employees have endorsed family leave as the workplace policy most helpful to them for managing their family caregiving and employment responsibilities (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Scharlach, 2001). Yet, the federal FMLA provides unpaid leave only to employees who have an immediate family member (spouse, child, or parent) with a serious health condition; the law does not require employers to provide leave for those who wish to care for a same-sex partner or a friend. Given the restrictions that govern the FMLA, the population represented by participants in our study would not be eligible for federal family leave benefits.

National Family Caregiver Support Program

In contrast to most policies, the National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP), passed by Congress in 2002, defines caregivers as adult family members, friends, or neighbors who provide care without pay and who have personal ties to the person needing assistance. NFCSP services are available to friends and same-sex partners who provide caregiving for adults 60 years of age or older. The program mandates that states work with local area agencies on aging and service providers to provide five basic services to family caregivers, including information and referral; assistance in gaining services; counseling, support groups, and training; respite care; and supplemental services. However, funding for the NFCSP is relatively limited and few services are available (Administration on Aging, 2004; National Association of State Units on Aging, 2007). Moreover, caregivers for chronically ill adults under age 60, who represent a large portion of the sample in this study, would not be eligible to receive assistance with caregiving.

Discrimination in Employment, Housing, and Public Accommodation

Twenty states and the District of Columbia currently ban discrimination based on sexual orientation in housing, public accommodation, and employment. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia explicitly ban discrimination based on gender expression and identity in housing, employment, and public accommodations (National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2008). This limited legal coverage leaves the majority of the U.S. population with no protection in employment against discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity at the federal, state, or local level (Human Rights Campaign, 2003). Thus, LGB caregivers and chronically ill adults who need care are at risk for serious economic problems and potential discrimination in housing and public accommodations, such as long-term care settings.

Legal Recognition of Primary Relationships

A study by the Congressional Budget Office (2004) has found 1,138 statutory provisions in which marital status is a factor used to determine eligibility for benefits, rights, and privileges. Many of these laws govern property rights, benefits, and taxation. Although marriage is associated with positive health outcomes (Herdt & Kertzner, 2006), this country (except in a few states) continues to deny marriage rights to same-sex couples. The federal 1996 Defense of Marriage Act explicitly bars recognition of same-sex couples and their access to federal benefits. Without legal recognition, same-sex couples are ineligible for spousal and survivor Social Security benefits and Medicaid benefits, including Medicaid spend-downs. Research (Alm, Badgett, & Whittington, 2000) has found that the resulting difference in Social Security income for same-sex couples compared with opposite-sex married couples is more than $5,000 per year. Although a few states offer marriage or civil unions to same-sex couples and numerous state, city, and county governments recognize domestic partnerships, the fact that same-sex unions are not recognized at the federal level leaves same-sex couples ineligible for federal benefits.

Among chronically ill LGB adults and their same-sex partners, legal recognition and protection are of paramount importance in the event of a health emergency or death. Under current law, if a lesbian or a gay man becomes incapacitated and has not executed a legal durable power of attorney for health care (as most in our study had not), most state laws mandate that a legally married spouse or biological family member be appointed as the decision maker to manage the person's affairs.

Conclusion

Given the significant demographic changes underway in the United States, caregiving research, services, and public policies must begin to be responsive to shifting family structures and diverse sexualities. As a result of the lack of legal recognition of same-sex partners and friends in providing care, most existing public policies intended to protect families in the event of serious illness or death are simply not available to chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. Furthermore, state-of-the-art projects, such as REACH (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health; Schulz, 2001), likely the largest and most comprehensive nationally funded caregiving intervention research aimed at diverse populations, have not addressed issues related to care within sexual-minority communities. To increase equity in caregiving support and services, it is imperative to more broadly define caregivers and those with chronic illness in order to understand, recognize, and support the pivotal role that same-sex partners, as well as friends, occupy in caregiving within diverse communities.

By adding to the understanding of the variations in care outcomes and the dyadic factors that influence chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers, the preliminary findings of this study have implications for developing research and for analyzing the application and development of public policies aimed at improving care outcomes among an increasingly diverse U.S. population. In future research, it will be important to test interventions designed to reduce risk factors (e.g., discrimination) and to increase the potentially protective nature of the dyadic relationship (e.g., components of dyadic relationship quality, such as problem solving and communication) to promote positive caregiving outcomes. By identifying specific variables within the social context and the care relationship that affect physical and mental health outcomes, strategies may be developed and tested to potentially enhance the protective aspects of the dyad, as well as the social environment, to support caregiving.

Although our research represents a preliminary cross-sectional study with inherent limitations, it is an important first step because so little is known about the experience of chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers. In this study, participants were drawn from a large urban community; the experiences of chronically ill adults and their caregivers in other settings may differ. In addition, the relatively small sample size limited not only our ability to detect differences but also the types of multivariate analyses that could be used. If caregiving research is to move forward, sexual orientation and gender identity and expression must be incorporated into national studies of caregiving. Future studies, with larger sample sizes, will be better positioned to further investigate the context of care, as well as how differing types of relationships and the use of formal supports affect caregiving outcomes and the trajectories of care.

In working toward a better understanding of the lives of chronically ill LGB adults and their caregivers, the integration of theoretical frameworks would expand the depth of the inquiry. Stress and coping theory has been used extensively in caregiving research, emphasizing the objective and subjective experiences of care and examining how coping processes interact with stress to result in caregiving outcomes. The conceptual framework of resilience is also relevant to understanding how protective mechanisms can buffer families from excessive demands and other risks in caregiving (Fredriksen-Goldsen, 2007b). In addition to expanding studies with respect to exploring various theoretical frameworks, future research would benefit from the separation of midlife, elder, and old-old (ages 75-plus) populations of LGB individuals into cohort studies.

A number of emerging issues have the potential to substantially affect caregiving in the future, including the demographic changes and the overall aging of the U.S. population, shifts in the nature of families, growing economic pressures, and the societal context of caregiving. Most current caregiving research, as well as today's programs and policies, simply do not recognize diverse sexualities or the changing nature of the American family. As the number of chronically ill LGB adults rapidly increases, addressing their needs and experiences becomes undeniably critical. As caregiving research begins to consider the social context of caregiving, stakeholders and policymakers will be better positioned to develop and test interventions to meet the needs of an increasingly diverse society.

Footnotes

Please direct all requests for permissions to photocopy or reproduce article content through the University of California Press's Rights and Permissions website, http://www.ucpressjournals.com/reprintInfo.asp

References

- Administration on Aging. The Older Americans Act, National Family Caregiver Support Program: Compassion in action. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alm J, Badgett MVL, Whittington LA. Wedding bell blues: The income tax consequences of legalizing same-sex marriage. National Tax Journal. 2000;53:201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JR, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in caregiving: The unexpected career. New York: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barker JC, Herdt G, de Vries B. Social support in the lives of lesbians and gay men at midlife and later. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC. 2006;3(2):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baronet AM. The impact of family relations on caregivers' positive and negative appraisal of their caretaking activities. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2003;52:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bengston VL. Beyond the nuclear family: The increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Berger RM. Gay and gray: The older homosexual man. 2nd. New York: Haworth Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Collins S, Chamberland L, Cormier R, Julien D, et al. Coming out to care: Caregivers of gay and lesbian seniors in Canada. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:490–504. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.4.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotman S, Ryan B, Cormier R. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. The Gerontologist. 2003;43:192–202. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, Ellen M, Tobias S. Family policy: Issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender families [Report] New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute; 2003. Jan 22, [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, South K, Spade J. Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender elders [Policy report] New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute; 2000. Nov 9, [Google Scholar]

- Cantor MH, Brennan M, Shippy RA. Caregiving among older lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender New Yorkers [Report] New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute; 2004. Jun 18, [Google Scholar]

- Clipp EC, Adinolfi AJ, Forrest L, Bennett CL. Informal caregivers of persons with AIDS. Journal of Palliative Care. 1995;11(2):10–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clunis M, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Freeman P, Nystrom N. Looking back, looking forward: The lives of lesbian elders. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. The potential budgetary impact of recognizing same-sex marriages [Report] Washington, DC: Author; 2004. Jun 21, [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Hershberger SL, Connell TA. Aspects of mental health among older lesbian, gay and bisexual adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2001;5:149–158. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deevey S. Older lesbian women: An invisible minority. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 1990;16(5):35–39. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19900501-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defense of Marriage Act, Pub L No 104-199, 100 Stat 2419. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ensel WM. Measuring depression: The CES-D scale. In: Lin N, Dean A, Ensel WM, editors. Social support, life events and depression. New York: Academic Press; 1986. pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein N, Baldwin L, Bishop D. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy. 1983;9:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Evashwick CJ. The continuum of long-term care: An integrated systems approach. Albany, NY: Delmar Learning; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, Pub L No 103-3. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF. Systems development for family caregiver support services. San Francisco: Family Caregiver Alliance; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen KI. Lesbian and gay caregiving. Paper Presented at the 18th Annual National Lesbian and Gay Health Conference; Seattle, WA. 1996. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen KI. Family caregiving responsibilities among lesbians and gay men. Social Work. 1999;44:142–155. doi: 10.1093/sw/44.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, editor. Caregiving with pride. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2007a. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. HIV/AIDS caregiving: Predictors of well-being and distress. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2007b;18(3/4):53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Scharlach AE. Families and work: New directions in the twenty-first century. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay SG, Wahler JJ. Lesbian aging: Review of a growing literature. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2002;14(3):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Gwyther LP. Caregiver well-being: A multidimensional examination of family caregivers of demented adults. The Gerontologist. 1986;26:253–259. doi: 10.1093/geront/26.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel N, Gallagher SK. Kinkeeping and distress: Gender, recipients of care, and work-family conflict. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55:598–608. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR, Dragowski EA. Caregiving and care receiving among older lesbian, gay and bisexual adults. In: Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, editor. Caregiving with pride. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2007. pp. 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hash KM. Preliminary study of caregiving and post-caregiving experiences of older gay men and lesbians. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2001;13(4):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hash KM, Cramer EP. Empowering gay and lesbian caregivers and uncovering their unique experiences through the use of qualitative methods. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2003;15(1/2):47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, Kertzner R. I do, but I can't: The impact of marriage denial on the mental health and sexual citizenship of lesbians and gay men in the United States. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC. 2006;3(1):33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Chopp R, Strohl D. Sexual stigma: Putting sexual minority health issues in context. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans-gender populations. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 171–208. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. States banning workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation. Washington, DC: Human Rights Campaign Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Campaign. Family and Medical Leave Act: FMLA-equivalent benefit for LGBT workers. 2009 Retrieved March 31, 2009, from http://www.hrc.org/issues/fmla_benefit.htm.

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Sayer AG, Archbold PG, Hornbrook MC, Stewart BJ. The enduring and contextual effects of physical health and depression on care-dyad mutuality. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007;30:84–98. doi: 10.1002/nur.20165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons KS, Zarit SH, Sayer AG, Whitlatch CJ. Caregiving as a dyadic process: Perspectives from caregiver and receiver. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:P195–P204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MetLife Mature Market Institute, Lesbian and Gay Aging Issues Network of the American Society on Aging, & Zogby International. Out and aging: The MetLife study of lesbian and gay baby boomers. Westport, CT: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Northridge ME. The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muraco A. Intentional families: Fictive kin ties between cross-gender, different sexual orientation friends. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:1313–1325. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Family Caregiving & AARP. Caregiving in the United States. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of State Units on Aging. Strategy brief: The Ombudsman Program and caregiver support [Report] Washington, DC: Author; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. State nondiscrimination laws in the US. 2008 Retrieved March 31, 2009, from http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/issue_maps/non_discrimination_7_08.pdf.

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polen MR, Green CA. Caregiving, alcohol abuse and mental health symptoms among HMO members. Journal of Community Health. 2001;26:285–301. doi: 10.1023/a:1010308612153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Division, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population prospects: The 2006 revision [Executive summary] 2006 Retrieved March 31, 2009, from http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2006/English.pdf.

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Royer A. Life with chronic illness: Social and psychological dimensions. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rozario PA, DeRienzis D. Familism beliefs and psychological distress among African American women caregivers. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:772–780. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R. Resources for enhancing Alzheimer's caregiver health, 1996–2001 [Computer file] Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI. Long-term care for the elderly with disabilities: Current policy, emerging trends, and implications for the twenty-first century. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- United States General Accounting Office. Long-term care: Current issues and future directions. Washington, DC: Author; 1995. Apr, [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The need for personal assistance with everyday activities: Recipients and caregivers Current population reports, household economic studies (Series P-70, No 19) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Statistical abstract of the United States 1996: The national data book. 116th. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Bernan; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Married-couple and unmarried-partner households: 2000 [Report] Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce; 2003. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM. The twain meet: Empirical explanations of sex differences in health and mortality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:282–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch C. Informal caregivers: Communication and decision making. Journal of Social Work Education. 2008;44:89–95. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336426.65440.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Screening for depression in primary care clinics: The CES-D and the BDI. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1990;20:259–277. doi: 10.2190/LYKR-7VHP-YJEM-MKM2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]