Abstract

We reported that murine tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells (TP-DC) could elicit tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. In some limited cases, TP-DC treatments in vivo could also result in regression of established subcutaneous tumors and lung metastases. By gene array analysis, we reported a high level of expression of a novel member of the cell surface class A scavenger receptor family, MARCO, by murine TP-DC compared to unpulsed DC. MARCO is thought to play an important role in the immune response by mediating binding and phagocytosis, but also in the formation of lamellipodia-like structures and dendritic processes. We have now examined the biologic and therapeutic implications of MARCO expressed by TP-DC. In vitro exposure of TP-DC to a monoclonal anti-MARCO antibody resulted in a morphologic change of rounding with disappearance of dendritic-like processes. TP-DC remained viable after anti-MARCO antibody treatment; had little, if any, change in production of IL-10, IL-12p70 and TNF-alpha; but demonstrated enhanced migratory capacity in a microchemotaxis assay. The use of a selective inhibitor showed MARCO expression to be linked to the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. In vivo, anti-MARCO antibody treated TP-DC showed better trafficking from the skin injection site to lymph node, enhanced generation of tumor-reactive IFN-gamma producing T cells, and improved therapeutic efficacy against B16 melanoma. These results, coupled with our finding that human monocyte-derived DC also express MARCO, could have important implications to human clinical DC vaccine trials.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-009-0813-5) contains supplementary material which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Vaccines, Dendritic cells, MARCO expression, Melanoma

Introduction

Many strategies involving the use of dendritic cells (DC) for inducing specific anti-tumor immune responses are being investigated. We [1–4] and others [5–7], have been studying DC loaded with dead tumor cells in vaccine approaches in experimental and clinical settings. DC pulsed with tumor-associated antigen(s) in the form of dead tumor cells (denoted TP-DC) can elicit specific T cell proliferation and CTL reactivity, and have shown efficacy in protecting naive mice from tumor challenge and in reducing the growth of tumors in vivo.

In our previous work, we uncovered by global gene analysis distinct changes in gene expression patterns because of dead cell loading of DC [8]. Most of the affected genes not surprisingly encoded a repertoire of proteins important for DC effector functions including cytokines, chemokines and receptors, antigen presentation, cell adhesion, and T cell activation. However, the transcript most highly expressed in TP-DC (with a ≥140-fold change increase) was shown to encode for macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (MARCO), a recently identified class A scavenger receptor (SR-A; [8–10]).

MARCO is an integral membrane component composed of three 52-kDa monomers [11]. Similar to the other SR-As, MARCO has a binding activity against Gram-positive and negative bacteria [12–17], modified low-density lipoproteins [11, 16], as well as oxide and other particles [14, 18, 19]. MARCO expression was earlier identified in a subpopulation of macrophages in the marginal zone of the spleen and in the lymph node of the medullary cord [11], and its expression was found to be up-regulated by bacterial LPS [13] or systemic bacterial sepsis [12, 13, 20]. Further, MARCO is thought to play an important role in macrophage participation in some immune responses by mediating binding and phagocytosis, but also in the formation of lamellipodia-like structures and of dendritic processes.

In this current report, we conducted a series of studies to determine whether targeting MARCO can invoke changes in the biology and function of murine TP-DC. Moreover, we evaluated whether modulation of this scavenger receptor can affect the anti-tumor immune response in vivo. Our studies were designed to provide rationale for the development of clinical vaccine trials in humans based on targeting MARCO and perhaps other scavenger receptors expressed by DC.

Materials and methods

Animals

Six to 12-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (denoted B6) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA, USA) and were maintained at the Animal Maintenance Facility at the Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, FL, USA). All mice were housed at least 1 week, and were age-matched before their usage in experiments.

Tumor cell line, lysate, and apoptotic cells

The B16-BL6 (denoted B16) melanoma was derived from the B16-F10 subline, syngeneic to B6 mice; it is highly aggressive and poorly immunogenic [21]. B16 cells were cultured in complete medium (CM; [22]) and maintained by serial in vitro passage. B16 tumor lysate (TL) was prepared as described previously [1, 2, 22]. Lysates were verified to be negative for endotoxin contamination by Pyrotell LAL test (detection limit, 0.03 EU/ml; Associates of Cape Cod, Inc., E. Falmouth, MA, USA). To induce apoptotic cells, B16 was irradiated with 30,000 rad or treated with UVB light (302 nm) for 20 min (equal to 200 mJ/cm2).

To stain B16 TL for microscopic or flow cytometric analyses of DC phagocytosis, PKH2 Green or PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit (Sigma) was utilized according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Trypsinized and washed B16 cells were first suspended in staining buffer. Staining was performed with 2 × 10−6 M PKH2 dye (1 × 107 cells/ml) for 5 min at room temperature. After staining, the cells were washed with CM once and with PBS thrice. TL of PKH2-stained B16 cells was made as described above. To prepare TL from freshly isolated B16 tumor, 1 × 105 B16 cells were injected sd into the flank of mice. Tumors were excised 3 weeks later, cleaned of capsule and necrotic areas, and disaggregated to single cells using an enzyme cocktail [1–3].

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

The rat anti-mouse MARCO mAb (ED31) producing hybridoma was a gift from Dr. Kraal (Vrije Universiteit, Netherlands). ED31 is an inhibitory rat IgG recognizing the ligand-binding domain of MARCO [12]; it interferes with the ligand binding activity of MARCO [12]. ED31 was purified from supernatants for further experiments (Ligocyte Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Bozeman, MT, USA). Normal rat IgG (Sigma) was used as a negative control.

DC, tumor loading, and mAb treatment

Highly enriched, bone marrow-derived DC were produced from B6 mice as described previously [1, 2, 22]. To load DC, tumor lysate (TL) was added in CM for 24 h at a DC:TL ratio of 1:3 cell equivalents [1, 2, 22]. For treatment of DC with mAbs, 20 μg/ml anti-MARCO mAb or control rat IgG was added to CM containing TL during the 24 h pulsing step. The treated, TP-DC were then washed twice with PBS and suspended in PBS for injection into mice. Viability of the DC after treatment with TL and mAbs was over 90% by trypan blue exclusion. Human DC were generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of normal volunteers, as described previously [3, 4]. Human DC were pulsed with lysate of two melanoma cell lines (MSM-M1 and MSM-M2) at a 1:3 ratio for 24 h alone or with 20 μg/ml mouse anti-human MARCO antibody (clone PLK1, Cell Sciences, Canton, MA, USA).

Immunofluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry

For immunofluorescence microscopy, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD11c mAb and appropriate isotype-matched control (BD Biosciences) were employed for DC staining. For cell surface staining, cells were washed with flow buffer (0.01% NaN3, 2% fetal bovine serum in PBS) and Fcγ III/II receptor blocking was performed by purified anti-mouse CD16/32 (BD Biosciences). The blocking mAb (1 μg/1 × 106 cells) was added to cells on ice for 10 min. Additional mAbs (1 μg/1 × 106 cells) for cell surface staining were then added on ice for an additional 30 min protected from light. After washing twice with flow buffer, the stained cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Data acquisition and analyses were performed by a FACScan flow cytometer and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences), respectively.

Treatment of DC with signaling pathway inhibitors

For some experiments, TP-DC were treated for 6 h with 10 μM inhibitors to p38 (SB203580), ERK1/2 (SL327), or JNK (SP600125) (all purchased from EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ, USA).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

The presence of p38, ERK, and JNK in untreated DC or DC pulsed with B16TL with or without anti-MARCO mAb treatment was examined by Western blotting and SDS-PAGE. Briefly, treated DC (1 × 107 cells) were lysed with 100 μl of NP-40 lysis buffer (Biosource, Camario, CA, USA) containing protease inhibitors (EMD Biosciences, Inc. San Diego, CA, USA). Proteins (100 μg per sample) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore Corp, MA, USA). Membranes were incubated for 1 h in 5% milk blocking buffer and then probed with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Antibodies to p38, phosphorylated p38, ERK1/2, phosphorylated ERK1/2, JNK, and phosphorylated JNK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). After thorough washing with TBST (0.01 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.002% Tween-20 in double-distilled H2O), the membranes were incubated with the appropriate HRP-labeled secondary antibody for 1 h. Following a final wash step, protein signal was detected by ECL plus Western blotting detection system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

For detection of MARCO mRNA, DC were either left unpulsed, or pulsed with 1 μg/ml LPS (from E. coli 0111: B4; Sigma), B16 apoptotic cells, or B16 TL for 24 h. To isolate mRNA from DC, RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) was used according to supplier instructions. For RT-PCR reactions, 100 ng mRNA was used to synthesize cDNA with Ready-to-Go RT-PCR beads (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, England). The cDNA synthesis reaction was performed at 37°C for 60 min followed by 95°C for 5 min. After the cDNA reaction, 400 nM primers were added into the reaction mixture. The following primers were used for murine MARCO PCR reactions; Sense: 5′-GCA CTG CTG CTG ATT CAA GTT C-3′, Anti-sense: 5′-AGT TGC TCC TGG CTG GTA TG-3′ (205 bp product). To detect MARCO expression in human cells, the following primers were used: Sense 5′-AAA TCA ATG TTC CAA AGC CCA AGA A-3′, Anti-sense: 5′-CCT GTT GCT CCA TCT CGT CCC ATA G-3′ (481 bp product). For GAPDH reactions, PCR primer pairs (mouse/rat GAPDH or human GAPDH: R&D Systems) were used. PCR amplification conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, amplification composed of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 57°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplification was performed using 35 cycles. Amplification products were separated on a 1% agarose gel, counter-stained with ethidium bromide, and viewed with Gel-Doc 200 (Biorad).

Detection of MARCO cell surface expression

TP-DC were washed with flow buffer and stained with rat anti-MARCO mAb or rat IgG1 as a negative control (Serotec) followed by the staining with Alexa Fluor 594 chicken anti-rat IgG and Alexa Fluor 488 hamster anti-mouse CD11c (both from Invitrogen Corp.). After the staining procedure, TP-DC were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 1% PFA for 1 h at room temperature. To examine MARCO expression by DC pulsed with labeled TL, we first cultured DC with PKH2 green or PKH26 red-stained B16 TL for 24 h. After the incubation, the DC were washed twice with PBS, stained with anti-MARCO mAb followed by Alexa Fluor 594 or Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-rat IgG, fixed with 1% PFA, and spun onto glass slides by a Shandon Cytospin-2 (International Medical Equipment, Inc., San Marcos, CA, USA) at 800 rpm for 5 min. The slides were then mounted with Gel/Mount (Biomeda Corp. Foster City, CA, USA) for anti-fading. Alternatively, slides were mounted with Vectashield mounting medium containing DAPI according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Slides were viewed with a fully automated, upright Zeiss Axio-ImagerZ.1 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA). Images were produced using the AxioCam MRm CCD camera and Axiovision version 4.5 software suite (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.).

Morphologic analysis of anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC

DC were cultured with different concentrations of anti-MARCO or anti-CD80 mAb together with B16 TL in Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide System (Nalge Nunc International Corp, Naperville, IL, USA). After overnight culture, TP-DC were stained with Wright’s and morphologic observation was performed under the light microscope.

Phagocytic activity of anti-MARCO mAb-treated DC

DC were co-cultured at 37°C with PKH2-stained (PKH2 Green Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit; Sigma) B16 TL for 24 h together with control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb. For a negative control, DC were co-cultured with stained B16 TL at 4°C. After 24 h culture, DC were stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD11c and the percentage of double positive CD11c/PKH2 cells were assessed by flow cytometry.

ELISA

DC were left unpulsed or pulsed with B16 TL together with control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb at 1 × 106 cells/ml in CM. For the positive control, DC were stimulated with 1 μg/ml LPS. After a 24 h incubation, supernatants were collected and cytokines (IL-10, IL-12p70, TNF-α) were measured by the BD OptEIA Mouse ELISA Set (BD Biosciences).

Microchemotaxis assay

To assess chemotactic activity of murine and human TP-DC in vitro, a microchemotaxis assay was performed in a 24-well plate format with 6.5-mm diameter, 5 μm pore polycarbonate Transwell insets (Coster, Cambridge, MA, USA), as described previously [22]. Murine (3 × 105) or (1 × 104) human TP-DC were placed into the upper chamber and 600 μl of CM containing 100 ng/ml (murine) or 250 ng/ml (human) SLC/CCL-21 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) was placed into the lower chamber. After 2 h, the upper chambers were removed and cell migration was measured. The migrating TP-DC samples were compared with input samples that did not involve microchemotaxis and is presented as the percentage of input migrating TP-DC.

Detection of migrated TP-DC in lymph nodes

DC were pulsed with B16 TL and control rat IgG or B16 TL and anti-MARCO mAb for 24 h and then washed twice with PBS. These TP-DC were stained with 2 × 10−6 M PKH26 dye (PKH26 Red Fluorescent Cell Linker Kit; Sigma) at 1 × 107 cells/ml for 5 min at room temperature, then washed with CM once and with PBS three times. TP-DC viability was over 90%. The PKH26-stained TP-DC were then suspended in PBS and 5 × 106 cells/100 μl (or PBS alone) were injected sd into the rear flanks of B6 mice (n = 4). Inguinal lymph nodes were collected 48 h later and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde solution at room temperature. The samples were plated onto dishes for microscopic examination and migrated TP-DC were observed by a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). Images were produced with the LSM 5 version 3,2,0115 software suite (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). TP-DC numbers were quantitated by counting the fluorescent cells across the entire single planar level of the lymph node using Image Pro Plus 6.2 (Media Cybernetics Inc., Silver Spring, MD, USA).

Anti-tumor therapy with TP-DC

B6 mice received 1 × 105 B16 melanoma cells sd in the right flank. DC were pulsed with B16 TL and treated with 20 μg/ml control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb for 24 h. Mice received 1 × 106 TP-DC (or PBS alone) in the left flank sd 3, 6, and 9 days after the tumor injection. Data are reported as the mean tumor area ± SD.

T cell IFN-γ production

B6 mice were immunized sd thrice, 3 days apart with the 1 × 106 DC pulsed with B16 TL and treated with control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb. Six days after final vaccination, spleens were removed under aseptic condition and erythrocytes-depleted lymphocytes were prepared from gently teased apart spleens. T cells in the lymphocytes were isolated with Mouse T-Cell Enrichment Column Kit (R&D Systems). After the isolation, T cells were suspended in CM at the concentration 1 × 106 cells/ml and cultured with or without TP-DC for 48 h. The concentration of T cell:TP-DC for the culture was 10:1. After 48 h incubation, supernatants were collected and IFN-γ was measured with a murine IFN-γ ELISA set (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA and Student’s t test were performed for comparisons of groups and to compare between two groups, respectively. All statistical evaluations employed GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was achieved at p < 0.05.

Results

Upregulation of MARCO expression by DC

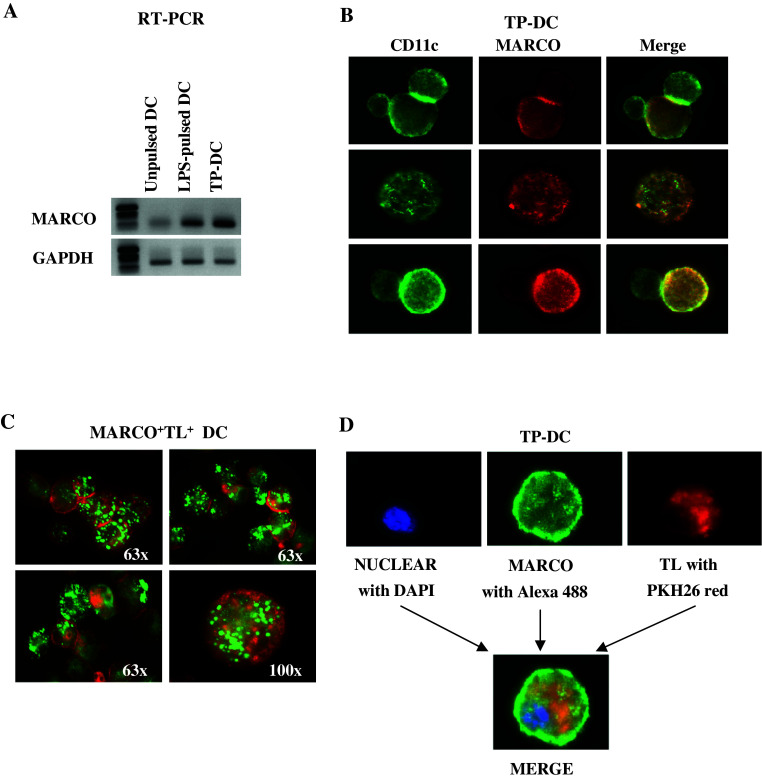

Murine bone marrow-derived DC were left unpulsed or exposed to 1 μg/ml LPS or B16 melanoma lysate. Twenty-four hours later, mRNA was extracted and MARCO expression was analyzed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1a). Both LPS- and TP-DC showed up-regulated MARCO expression. Upregulation of MARCO mRNA expression in DC could also be detected following their exposure to either UV-treated or irradiated, intact B16 melanoma cells [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Human monocyte-derived DC were examined by RT-PCR for the presence of MARCO transcript (i.e. a 481 bp PCR product) as well. MARCO was expressed by both human lymph node cells and human DC (lanes 1 and 2, respectively; Fig. S2).

Fig. 1.

Enhancement of MARCO transcript expression in DC loaded pulsed with LPS or loaded with tumor lysate (a). Total RNA from unpulsed (UP)-DC and DC pulsed with LPS or loaded with B16 melanoma lysate as indicated, were analyzed by RT-PCR for MARCO transcript expression. Amounts of mRNA were adjusted to give comparable GAPDH signals. Experiment was repeated twice with similar results. b, c, d Fluorescence microscopy reveals MARCO expression on the surface of DC. DC were first cultured for 24 h with unstained or stained TL then labeled for surface markers as described in “Materials and methods”. b Not all CD11c+ (Alexa Fluor 488, green) cells co-express MARCO (Alexa Fluor 594, red). MARCO cell surface expression can be observed on DC loaded with labeled either: c PKH2-stained (green) or d PKH26-stained (red) B16 melanoma lysate

To visualize cell surface expression of MARCO, TP-DC were first stained with fluorescent-labeled anti-MARCO and anti-CD11c mAbs. As can be seen in Fig. 1b, many, but not all, of the CD11c+ TP-DC co-exhibited MARCO expression (i.e. 67–82% over a 72 h period of B16 melanoma lysate loading), which appeared as a uniform surface distribution pattern. We then directly co-examined the expression of MARCO on the cell surface of B16 tumor lysate-captured DC. In this case, DC were co-cultured with PKH2 Green (Fig. 1c) or PKH26 Red (Fig. 1d)-stained B16 TL for 24 h before labeling with anti-MARCO mAb.

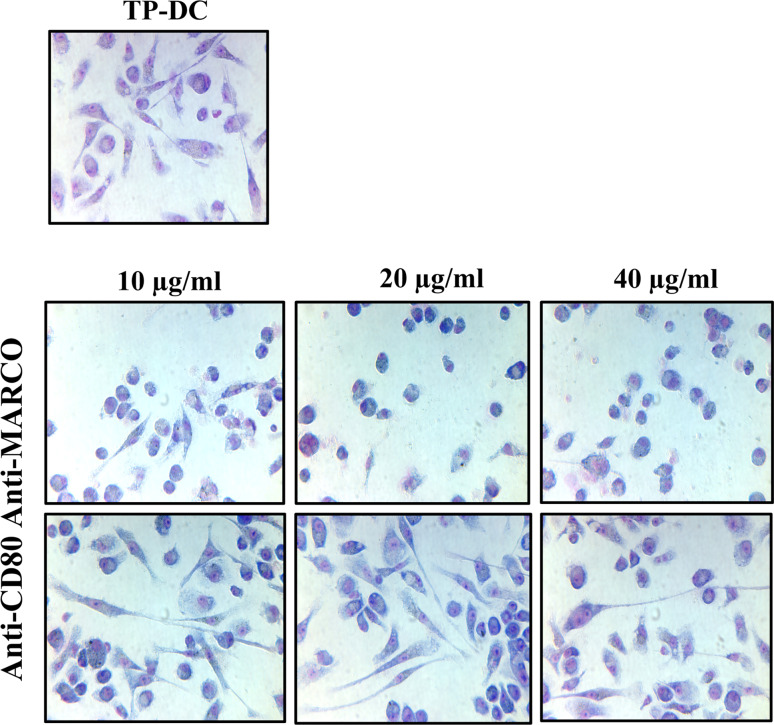

Functional assessment of MARCO expressed by DC

We next examined the effect(s) of exposure to anti-MARCO mAb on certain DC biologic properties. First, we noted that overnight exposure of DC to various concentrations of anti-MARCO mAb (10, 20, and 40 μg/ml) together with B16 melanoma lysate resulted in a rounded morphology with loss of membrane dendritic processes (Fig. 2 Middle), compared to untreated TP-DC (Fig. 2 Upper); DC remained highly viable. The change in morphology was not observed when such DC were similarly treated with control rat IgG (not shown) or anti-CD80 mAb directed to a second, cell surface expressed molecule (Fig. 2 Lower).

Fig. 2.

Exposure of B16 melanoma lysate-loaded DC (Upper) to anti-MARCO mAb in vitro leads to cell rounding and loss of dendritic processes (Middle). Such morphologic changes were not observed following incubation of the DC to antibody directed toward a second cell surface expressed molecule, CD80 (Lower). Representative of two separate experiments

We also examined phagocytic activity of DC upon treatment with anti-MARCO mAb. DC were co-cultured with PKH2 Green stained B16 TL and control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb. DC were then stained with anti-CD11c antibody and double positive cells were measured. As shown in Fig. S3, anti-MARCO mAb treatment of unpulsed DC (i.e. targeting the “steady state” level MARCO surface expression) did not adversely impact subsequent uptake of B16 TL (% CD11c+ PKH2+ cells (mean ± SD): no Ab, 20.9 ± 1.2; rat IgG, 20.4 ± 1.2; anti-MARCO mAb, 20.8 ± 0.5]. Similarly, little, if any, change was detected in TP-DC production of IL-10, IL-12p70 and TNF-alpha cytokines following anti-MARCO mAb treatment (Fig. S4)

Microchemotaxis assays were then performed to assess the effect of anti-MARCO mAb on chemotactic activity of DC in vitro (Fig. S5). We had shown previously that SLC/CCL-21 is a potent chemoattractant of DC in vitro and in vivo [22]. TP-DC treated with anti-MARCO mAb showed improved migration as measured by the number of CD11c+ I-Ab+ cells appearing in the lower chamber (% migrating cells mean ± SD): control rat IgG, 76.4 ± 2.4; anti-MARCO mAb, 94.5 ± 3.3, *p<0.05], which was similar to LPS-treated TP-DC (93.8 ± 7.3). Similar to the mouse, enhanced in vitro migration of human TP-DC, as measured in microchemotaxis assays, was also observed following anti-human MARCO mAb exposure (Fig. S6).

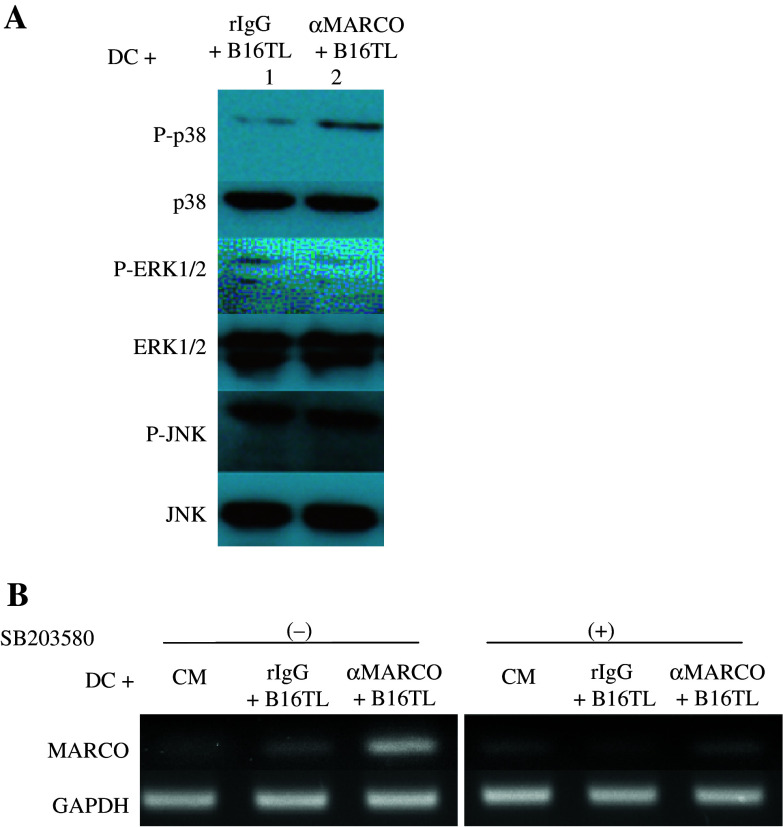

MARCO expression is linked to the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway

We investigated the involvement of certain signaling pathways in TP-DC with respect to the effect of exposure to anti-MARCO mAb and the expression of MARCO. Figure 3a shows by Western blot analysis that exposure to anti-MARCO mAb leads to an elevation of phosphorylated (P)-p38 (lane 2) but not P-ERK 1/2 or P-JNK. Using known inhibitors of signaling pathways, we next examined their effect, if any, on MARCO expression. The results are shown in Fig. 3b. Exposure of TP-DC to anti-MARCO mAb results in a further increase in MARCO gene expression, which is eliminated by the use of the selective p38 MAPK inhibitor, SB203580. In contrast, the use of ERK and JNK inhibitors had no effect (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of anti-MARCO mAb-treated DC (a). DC were treated for 6 h with B16TL + 20 μg/ml rIgG (lane 1) or B16TL + 20 μg/ml anti-MARCO mAb (lane 2). Blots were probed for phosphorylated-p38 (P-p38), p38, phosphorylated ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2), ERK1/2, phosphorylated-JNK (P-JNK), and JNK as indicated. RT-PCR analysis of MARCO expression after inhibition of the p38 pathway (b). DC were treated with CM, B16TL + rIgG or B16TL + anti-MARCO mAb for 24 h. In addition, cells were treated with 10 μM of the p38 inhibitor, SB203580. GAPDH served as the control

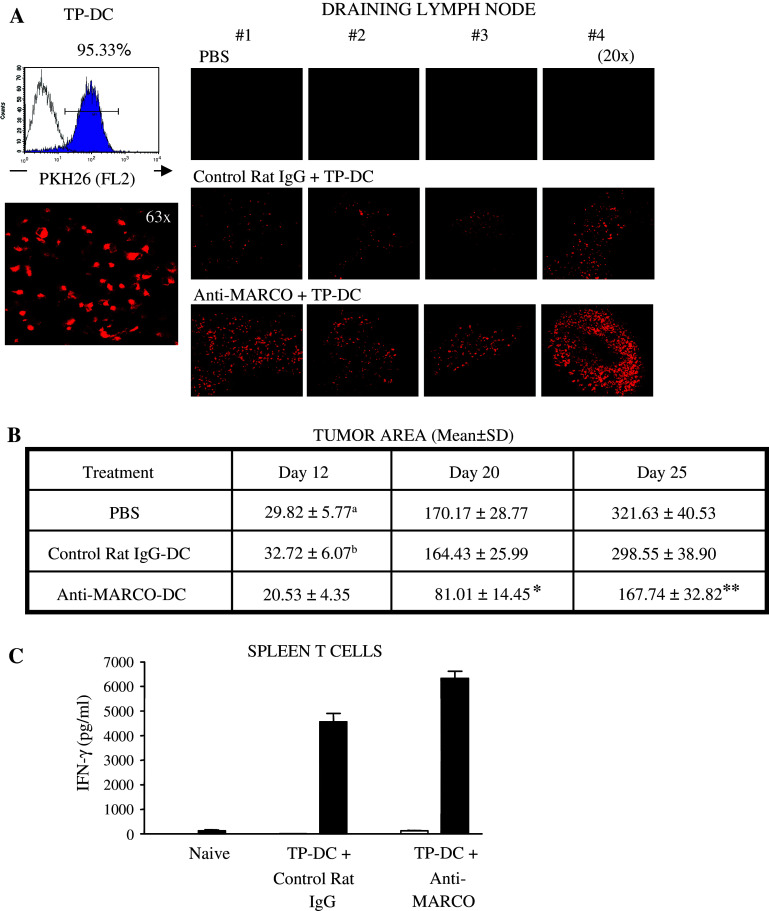

Targeting MARCO enhances both DC migration to lymph node and anti-tumor efficacy in vivo

We next examined in vivo whether targeting MARCO would affect the migration of TP-DC into lymph nodes after subdermal (sd) injection. DC were first stained with PKH26-red dye, and after staining >95% were confirmed positive by both flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. These DC were exposed to B16 TL together with control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb and injected sd into cohorts of mice. The draining lymph nodes were collected 48 h later to evaluate the presence of TP-DC. As shown in Fig. 4a, anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC demonstrated heightened lymph node accumulation, which was also confirmed quantitatively by counting the number of fluorescent cells (Fig. S7). Of note, these cells could also be detected to some extent in the spleen compared to control rat IgG treated DC (not shown).

Fig. 4.

Enhanced trafficking of skin injected, B16 melanoma lysate-loaded DC to lymph node following exposure to anti-MARCO mAb (a). DC were first stained with PKH26-red dye, and after staining >95% were confirmed positive by both flow cytometry (Upper, left) and confocal microscopy (Lower, Left). These DC were exposed to B16 melanoma lysate together with control rat IgG (Middle, Right) or anti-MARCO mAb (Lower, Right) and injected (5 × 106 cells) subdermally into cohorts of individual mice. The draining inguinal lymph nodes were collected 48 h later to evaluate arriving TP-DC. Representative of two separate experiments. b Enhanced anti-tumor efficacy in vivo following TP-DC exposure to anti-MARCO mAb. Mice received 1 × 105 viable B16 melanoma cells subdermally in the right flank. DC were loaded with B16 TL and treated with 20 μg/ml control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb. Mice received 1 × 106 TP-DC (or PBS alone) subdermally in the left flank 3, 6, and 9 days after tumor injection. Data are shown as mean tumor area ± SD and are a compendium of three separate experiments, combined. *p < 0.01 vs. control rat IgG-DC or PBS. **p < 0.02 vs. control rat IgG; p < 0.01 vs. PBS. (C) Enhancement of IFN-γ production by splenic T cells by immunization with anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC. Naïve or TP-DC DC immunized mice served as splenic T cell donors. The T cells were restimulated in vitro as described in “Materials and methods”. Open and solid bars represent T cells alone and T cells plus B16 TP-DC, respectively. Values are mean ± SD of triplicate wells. Representative of two experiments

Because enhanced migration of TP-DC to lymph nodes could be achieved by anti-MARCO mAb treatment, we then investigated its impact on vaccine efficacy against established B16 melanoma. Mice harboring B16 melanoma in the skin were injected sd thrice, 3 days apart, with 1 × 106 TP-DC exposed to control rat IgG or anti-MARCO mAb. The results of three combined experiments are shown in Fig. 4b. In this treatment model, control rat IgG-treated TP-DC did not show an anti-tumor effect (mean tumor diameter at day 25 (mm2 ± SD): PBS, 321.63 ± 40.53; control rat IgG-DC, 298.55 ± 38.90]. In contrast, the injection of anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC resulted in an approximate 50% tumor growth inhibition (167.74 ± 32.82, ** p < 0.01). Thus, targeting MARCO on TP-DC could switch an ineffective vaccine to one that could inhibit the growth of a poorly immunogenic, highly aggressive melanoma.

Targeting MARCO on DC enhances anti-tumor T cell reactivity

To next examine the induction of a cellular immune response following anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC injection, we measured IFN-γ production by T cells from immunized mice. Splenic T cells were re-stimulated in vitro with or without the respective TP-DC. As shown in Fig. 4c, T cells from mice immunized with anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC produced a greater amount of IFN-γ compared to those from control rat IgG-treated TP-DC immunized mice (6,333 ± 705 pg/ml vs. 4,561 ± 843 pg/ml, respectively, *p < 0.01).

Discussion

Collectively, our findings reported herein demonstrate that targeting MARCO expression can enhance both the trafficking and anti-tumor efficacy of TP-DC. By microarray analysis, we reported earlier that MARCO mRNA was identified as one of the most up-regulated transcripts in TP-DC [8]. The fact that MARCO expression also increased when using lysates from fresh normal tissues to pulse DC has suggested that MARCO upregulation is an event linked to a general phagocytosis [8]. MARCO expression is not detected, however, on the surface of all CD11c+ DC and the reason(s) behind this observation remains to be determined. However, we have not found any clear-cut preferential expression of MARCO on a particular CD11c+ cell subtype by FACS analysis. The use of a selective inhibitor, SB203580, showed MARCO expression to be linked to the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. These data are consistent with those of others who have examined the role(s) of distinct signaling pathways (i.e. p38 MAPK, JNK1, ERK) in DC activation, survival, and function [23, 24]. In this regard, the p38 MAPK pathway has been linked to DC actin cytoskeleton remodeling [25], DC maturation [26], and increasing DC-based immunization to model and tumor-associated antigens [27]. In preliminary studies, we have not found, however, a link between the NF-κB pathway, apoptosis, and MARCO expression by TP-DC.

Precedent exists for monoclonal antibodies altering the trafficking of immune cells in vivo based on the biology of the targeted surface molecule. For example, the widely used macrophage antibody 5C6 has been shown to profoundly influence inflammatory cell recruitment in vivo [28]. Ex vivo generated DC in both mouse and humans have very limited movement from subcutaneous or intradermal injection sites to locally draining lymph node(s) and essentially none to spleen [29, 30]. This limitation is considered one of the significant weaknesses in the use of DC-based vaccines to date. It is also clear that the intravenous route of administration of DC has proven ineffective to target multiple peripheral lymphoid organs as well. Most DC administered by this route appear to be trapped rapidly in the capillaries of the lungs, in the spleen, and in the liver where the DC then tend to be cleared. Immunization by this route is generally inadequate and some investigators have abandoned the intravenous delivery of DC both in animal studies and in human clinical trials. Recently, the direct intranodal delivery of antigen-loaded DC has gained much favor, as this route appears to be somewhat superior for inducing immune responses compared to the subcutaneous or intradermal route [29–31]. However, it is logistically and technically impractical to deliver a large number of DC to a single lymph node as well as to target multiple lymph nodes by the current methodology.

Studies have been reported elsewhere showing that scavenger receptors have avid adherence to matrix molecules and to other cells [32, 33]. In an allergic airway inflammation model, scavenger receptor deficient innate DC revealed a higher level of migration into thoracic lymph nodes than control, wild-type DC [34]. We believe that the enhanced arrival of TP-DC at peripheral lymphoid tissues by targeting MARCO is responsible for the enhanced anti-tumor T cell reactivity that we have detected. This correlation is supported by our findings that TP-DC treated with anti-MARCO mAb or control IgG have the same levels of antigen (OVA or B16 tumor lysate) presentation capacity in vitro as measured by IFN-γ secretion and cytotoxicity by the stimulated T cells (data not shown) and produce similar levels of endogenous cytokines (i.e. IL-10, IL-12, and TNF-α) in vitro (Fig. S4). Moreover, murine bone marrow-derived TP-DC are known to already possess a high level of surface expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules—an indication of a more mature phenotype [35], which was not further increased by exposure of TP-DC to anti-MARCO mAb (data not shown).

The finding of improved in vitro migration of anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC, as measured in microchemotaxis assays, also correlates with the morphologic shape change (i.e. rounding with loss of dendritic processes) of TP-DC following anti-MARCO mAb exposure. In this regard, MARCO expression has been shown to be sufficient to induce actin cytoskeleton rearrangement [9] and the change in morphology observed with anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC might also play a participatory role in the increased migratory behavior observed in the microchemotaxis assay as well as in vivo.

It should be noted that we have been unsuccessful in reliably isolating and purifying the in vivo migrated anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC from lymph node in order to accurately quantify their number by FACS analysis. In our experience, employing Ca2+-free medium and prescribed enzymes and gradient methodologies [36], have yielded poor and variable recoveries. We attribute this problem to the adherence of DC to stromal elements, which has been recognized by others [37, 38]. Thus, we opted for confocal microscopic observation (Fig. 4a) and quantitating the number of fluorescent cells at a single planar level only by imaging analysis software (Fig. S7).

We have recently developed MARCO gene knockout mice on the B6 background, and DC generated from their bone marrow appear to display similar enhancements in lymph node migration and anti-tumor efficacy as those of wild-type mice treated with anti-MARCO mAb (Komine, H., Matsushita, N., Pilon-Thomas, S., and Mulé, J.J., Manuscript in Preparation). We believe that MARCO, and perhaps other SR-A [39], gene knockout mice will prove valuable in mechanistic studies aimed at understanding the role of such molecules in DC regulation of anti-tumor immunity. These studies are currently underway. In addition, RNA interference can be employed as another strategy to evaluate the function of MARCO expressed by TP-DC [40]. Moreover, because we showed earlier that DC transcribe and specifically express MARCO on their cell surface in response to loading with different histologic types of tumor [8], it will also be important to determine whether the enhanced anti-melanoma efficacy of anti-MARCO mAb-treated TP-DC as a vaccine will extend to the treatment of other tumor types as well. Last, our finding that human monocyte-derived DC also express functional MARCO raises the consideration of its targeting (and conceivably other SRAs) in future human clinical settings that employ DC-based vaccines [41].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of Moffitt Cancer Center’s shared resources (analytical microscopy, biostatistics, flow cytometry and mouse models cores) for superb technical assistance and support. This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (5 R01 CA071669-10).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fields RC, Shimizu K, Mulé JJ. Murine dendritic cells pulsed with whole tumor lysates mediate potent antitumor immune responses in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9482–9487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asavaroengchai W, Kotera Y, Mulé JJ. Tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells can elicit an effective antitumor immune response during early lymphoid recovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:931–936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022634999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang AE, Redman BG, Whitfield JR, Nickoloff BJ, Braun TM, Lee PP, Geiger JD, Mulé JJ. A phase I trial of tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells in the treatment of advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1021–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiger JD, Hutchinson RJ, Hohenkirk LF, McKenna EA, Yanik GA, Levine JE, Chang AE, Braun TM, Mulé JJ. Vaccination of pediatric solid tumor patients with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells can expand specific T cells and mediate tumor regression. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8513–8519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morse MA, Coleman RE, Akabani G, Niehaus N, Coleman D, Lyerly HK. Migration of human dendritic cells after injection in patients with metastatic malignancies. Cancer Res. 1999;59:56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman RM, Banchereau J. Taking dendritic cells into medicine. Nature. 2007;449:419–426. doi: 10.1038/nature06175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman RM. Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. Dendritic cells: versatile controllers of the immune system. Nat Med. 2007;13:1155–1159. doi: 10.1038/nm1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grolleau A, Misek DE, Kuick R, Hanash S, Mulé JJ. Inducible expression of macrophage receptor MARCO by dendritic cells following phagocytic uptake of dead cells uncovered by oligonucleotide arrays. J Immunol. 2003;171:2879–2888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granucci F, Petralia F, Urbano M, Citterio S, Di Tota F, Santambrogio L, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. The scavenger receptor MARCO mediates cytoskeleton rearrangements in dendritic cells and microglia. Blood. 2003;102:2940–2947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Re F, Belyanskaya SL, Riese RJ, Cipriani B, Fischer FR, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Brosnan C, Stern LJ, Strominger JL, Santambrogio L. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces an expression program in neonatal microglia that primes them for antigen presentation. J Immunol. 2002;169:2264–2273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elomaa O, Kangas M, Sahlberg C, Tuukkanen J, Sormunen R, Liakka A, Thesleff I, Kraal G, Tryggvason K. Cloning of a novel bacteria-binding receptor structurally related to scavenger receptors and expressed in a subset of macrophages. Cell. 1995;80:603–609. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90514-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Laan LJ, Dopp EA, Haworth R, Pikkarainen T, Kangas M, Elomaa O, Dijkstra CD, Gordon S, Tryggvason K, Kraal G. Regulation and functional involvement of macrophage scavenger receptor MARCO in clearance of bacteria in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:939–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Laan LJ, Kangas M, Dopp EA, Broug-Holub E, Elomaa O, Tryggvason K, Kraal G. Macrophage scavenger receptor MARCO: In vitro and in vivo regulation and involvement in the anti-bacterial host defense. Immunol Lett. 1997;57:203–208. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(97)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arredouani MS, Palecanda A, Koziel H, Huang YC, Imrich A, Sulahian TH, Ning YY, Yang Z, Pikkarainen T, Sankala M, Vargas SO, Takeya M, Tryggvason K, Kobzik L. MARCO is the major binding receptor for unopsonized particles and bacteria on human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;175:6058–6064. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elshourbagy NA, Li X, Terrett J, Vanhorn S, Gross MS, Adamou JE, Anderson KM, Webb CL, Lysko PG. Molecular characterization of a human scavenger receptor, human MARCO. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:919–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kraal G, van der Laan LJ, Elomaa O, Tryggvason K. The macrophage receptor MARCO. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:313–316. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukhopadhyay S, Chen Y, Sankala M, Peiser L, Pikkarainen T, Kraal G, Tryggvason K, Gordon S. MARCO, an innate activation marker of macrophages, is a class A scavenger receptor for Neisseria meningitidis . Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:940–949. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palecanda A, Paulauskis J, Al-Mutairi E, Imrich A, Qin G, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Tryggvason K, Koziel H, Kobzik L. Role of the scavenger receptor MARCO in alveolar macrophage binding of unopsonized environmental particles. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1497–1506. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arredouani M, Yang Z, Ning Y, Qin G, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Kobzik L. The scavenger receptor MARCO is required for lung defense against pneumococcal pneumonia and inhaled particles. J Exp Med. 2004;200:267–272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshimatsu M, Terasaki Y, Sakashita N, Kiyota E, Sato H, van der Laan LJ, Takeya M. Induction of macrophage scavenger receptor MARCO in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis indicates possible involvement of endotoxin in its pathogenic process. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura K, Yoshikawa N, Yamaguchi Y, Kagota S, Shinozuka K, Kunitomo M. Characterization of mouse melanoma cell lines by their mortal malignancy using an experimental metastatic model. Life Sci. 2002;70:791–798. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirk CJ, Hartigan-O’Connor D, Nickoloff BJ, Chamberlain JS, Giedlin M, Aukerman L, Mulé JJ. T cell-dependent antitumor immunity mediated by secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine: augmentation of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2062–2070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rescigno M, Martino M, Sutherland CL, Gold MR, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cell survival and maturation are regulated by different signaling pathways. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2175–2180. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakahara T, Moroi Y, Uchi H, Furue M. Differential role of MAPK signaling in human dendritic cell maturation and Th1/Th2 engagement. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;42:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West MA, Wallin RPA, Matthews SP, Svensson HG, Zaru R, Ljunggren H-G, Prescott AR, Watts C. Enhanced dendritic cell antigen capture via toll-like receptor-induced actin remodeling. Science. 2004;305:1153–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1099153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arrighi J-F, Rebsamen M, Rousset F, Kindler V, Hauser C. A critical role for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the maturation of human blood-derived dendritic cells induced by lipopolysaccharide, TNF-α, and contact sensitizers. J Immunol. 2001;166:3837–3845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escors D, Lopes L, Lin R, Hiscott J, Akira S, Davis RJ, Collins MK. Targeting dendritic cell signaling to regulate the response to immunization. Blood. 2008;111:3050–3061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-122408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen H, Gordon S. Monoclonal antibody to the murine type 3 complement receptor inhibits adhesion of myelomonocytic cells in vitro and inflammatory cell recruitment in vivo. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1685–1701. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adema GJ, de Vries JM, Punt CJA, Figdor CG. Migration of dendritic cell based cancer vaccines: in vivo veritas? Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verdijk P, Aarntzen EH, Punt CJ, de Vries IJ, Figdor CG. Maximizing dendritic cell migration in cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:865–874. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.7.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambert LA, Gibson GR, Maloney M, Durell B, Noelle RJ, Barth RJ., Jr Intranodal immunization with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells enhances protective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:641–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.el Khoury J, Thomas CA, Loike JD, Hickman SE, Cao L, Silverstein SC. Macrophages adhere to glucose-modified basement membrane collagen IV via their scavenger receptors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10197–10200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson MC, Guinamard R, Bolland S, Sankala M, Steinman RM, Ravetch JV. Macrophages control the retention and trafficking of B lymphocytes in the splenic marginal zone. J Exp Med. 2003;198:333–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arredouani MS, Franco F, Imrich A, Fedulov A, Lu X, Perkins D, Soininen R, Tryggvason K, Shapiro SD, Kobzik L. Scavenger receptors SR-AI/II and MARCO limit pulmonary dendritic cell migration and allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;178:5912–5920. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotera Y, Shimizu K, Mulé JJ. Comparative analysis of necrotic and apoptotic tumor cells as a source of antigen(s) in dendritic cell-based immunization. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8105–8109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Inaba K, Pack M, Inaba M, Sakuta H, Isdell F, Steinman RM. High levels of a major histocompatibility complex II-self peptide complex on dendritic cells from the T cell areas of lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1997;186:665–672. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson HL, O’Neill HC. Murine dendritic cell development: difficulties associated with subset analysis. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;81:239–246. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.t01-1-01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi K, Kenji A, Norihiro T, Eisaku K, Takashi O, Kazuhiko H, Tadashi Y, Tadaatsu A. Morphological interactions of interdigitating dendritic cells with B and T cells in human mesenteric lymph nodes. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:131–138. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61680-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, Takashima Y, Kawabe Y, Cynshi O, Wada Y, Honda M, Kurihara H, Aburatani H, Doi T, Matsumoto A, Azuma S, Noda T, Toyoda Y, Itakura H, Yazaki Y, Kodama T. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386:292–296. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brummelkamp T, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulé JJ. Dendritic cells: at the clinical crossroads (Invited Commentary) J Clin Invest. 2000;105:707–708. doi: 10.1172/JCI9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.