Abstract

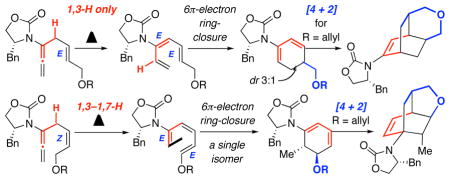

A new torquoselective ring-closure of chiral amide-substituted 1,3,5-hexatrienes and its application in tandem with [4 + 2] cycloaddition are described. The trienes were derived via either a 1,3-H or 1,3-H–1,7-H shift of α-substituted allenamides, and the entire sequence through the [4 + 2] cycloaddition could be in tandem from allenamides.

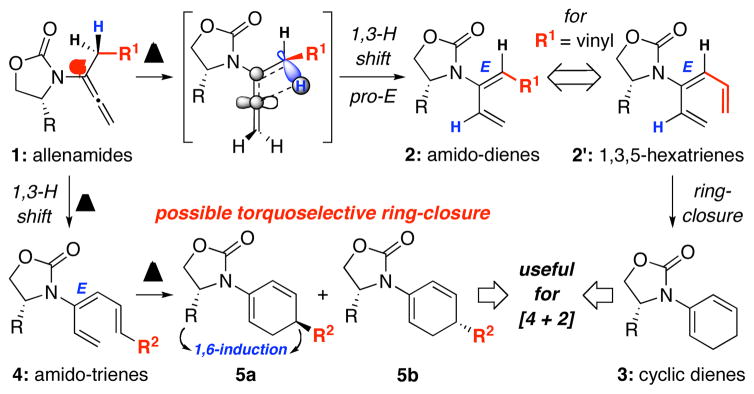

We recently reported isomerizations of α-substituted allenamides 1 to give amido-dienes 2 via stereoselective 1,3-H shift [Scheme 1].1 In addition, with R = vinyl, the resulting 1,3,5-hexatrienes 2′ were found to be well suited for a 6π-electron electrocyclic ring-closure that could be in tandem with the 1,3-H shift, leading to novel chiral cyclic amido-dienes 32,3 directly from allenamides.4,5 The rapid access of 1,3,5-hexatrienes via a simple isomerization of allenes6–8 allowed us to envision a new torquoselective ring-closure9–13 involving chiral amido-trienes 4. This asymmetric transformation could potentially lead to a remote 1, 6-stereochemical induction while affording cyclic amido-dienes 5, which should be useful for cycloadditions. We communicate here this torquoselective process and its application in tandem with [4 + 2] cycloadditions.

Scheme 1.

A New Torquoselective Pericyclic Ring-Closure.

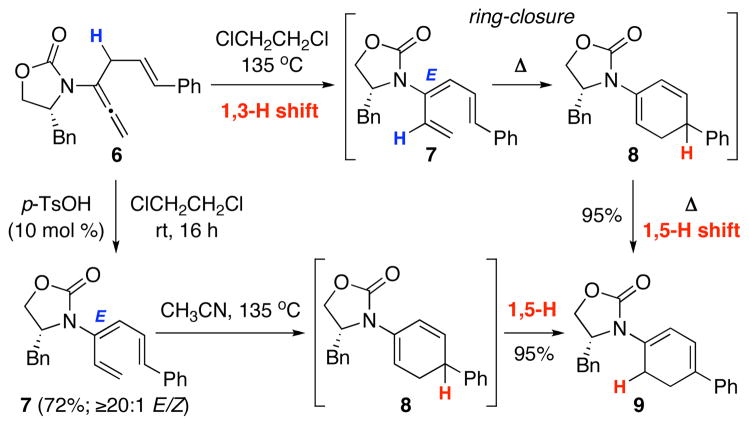

Our intention was quickly met with two unexpected findings. Initially, when heating allenamide 614,15 in ClCH2CH2Cl at 135 °C, instead of isolating the desired amido-diene 8 from ring-closure of the triene 7, we found 915 in almost quantitative yield, thereby implying a 1,5-H shift had taken place [Scheme 2]. Similar results were attained when using triene 7 generated from 6 via an acid-promoted 1,3-H shift using 10 mol % p-TsOH.

Scheme 2.

Complication with the 1,5-H Shift into Conjugation.

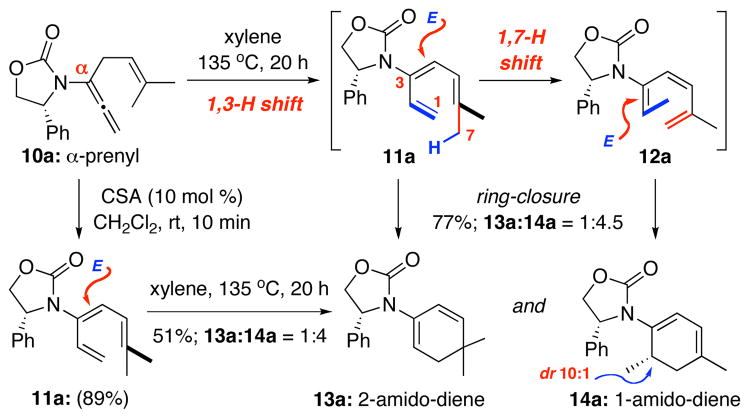

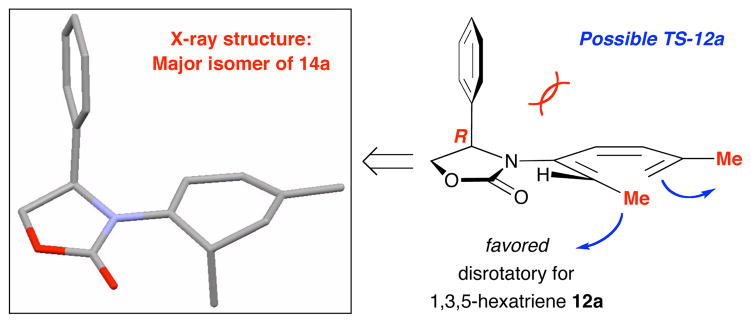

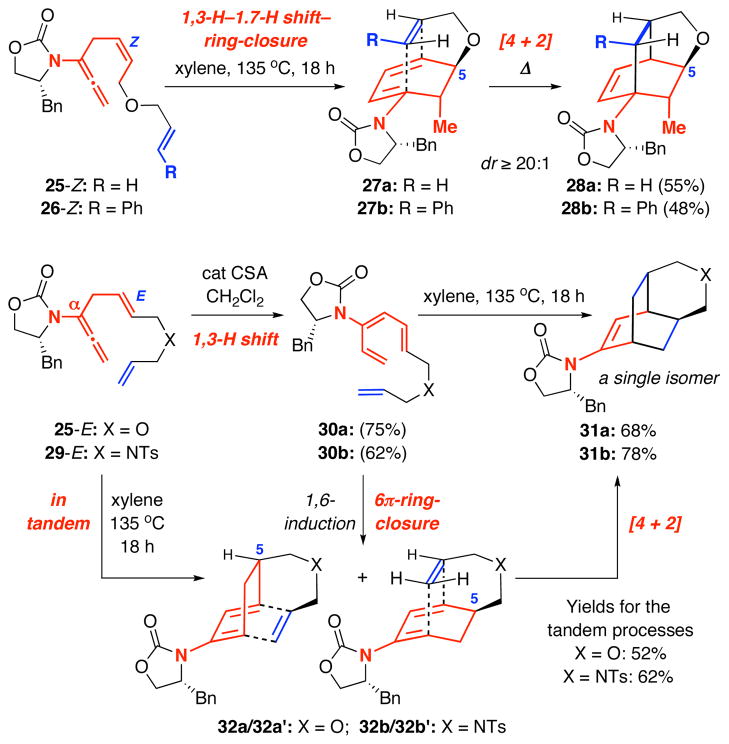

We quickly made a minor substrate adjustment to prevent such 1,5-H shift, but that led to the second unexpected finding as shown in Scheme 3. Heating α-prenylated allenamide 10a led to a mixture of two ring-closure products: The desired 2-amido diene 13a and the unexpected 1-amdio-diene 14a in 1:4.5 ratio with 14a being a 10:1 diastereomeric mixture. The latter implied the presence of amido-triene 12a, which could be rationalized through an antarafacial 1,7-H shift9,17 from the initial amido-triene 11a, via the methyl group [in red] syn to the terminal olefin [in blue]. More importantly, stereochemistry for the major isomer of 14a could be assigned using its single crystal X-ray structure [Figure 1]. This unambiguous assignment suggests that a favored disrotatory course could proceed through the transition state as shown for amido-triene 12a.

Scheme 3.

An Unexpected Competing 1,7-H Shift.

Figure 1.

A Torquoselective Disrotatory-Ring Closure.

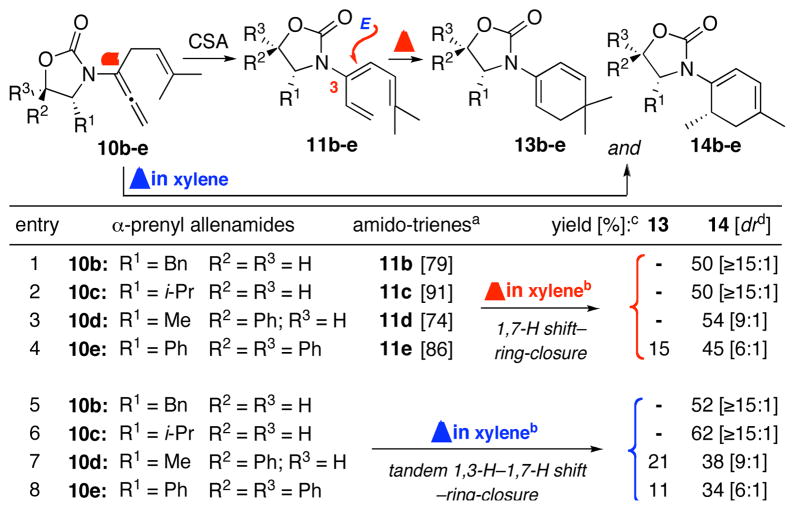

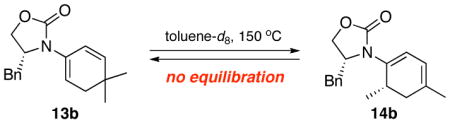

The tandem 1,3-H–1,7-H shift appears to be general whether commencing from amido-trienes 11b–e [entries 1–4 in Table 1] or directly from α-prenylated allenamides 10b–e [entries 5–8]. It is noteworthy that in the case of allenamide 10b and 10c, cyclic amido-dienes 14b and 14c were the only products resulting from a tandem 1,3-H–1,7-H shift–pericyclic ring-closure. In addition, there was no equilibration between 13 and 14 under the reaction conditions.18

Table 1.

A Tandem 1,3-H–1,7-H Shift–Pericyclic Ring-Closure.

|

All 3-amido-trienes 11b–e were attained from the respective allenamides 10b–e via 1,3-H shift promoted by CSA (10 mol %). Reactions were run in CH2Cl2 at rt for 10 min, and isolated yields are shown in the respective brackets.

For all entries: concn = 0.10 M; temp = 135 °C; time = 20 h.

Isolated yields.

Ratios determined by 1H and/or 13C NMR.

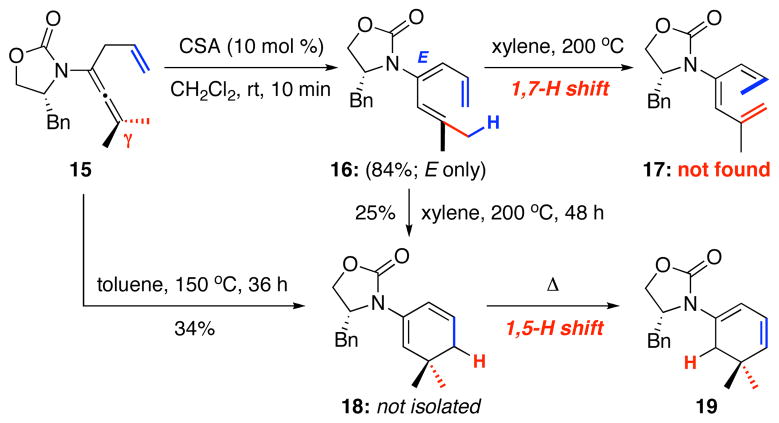

Probing further mechanistically, we found two phenomena associated with this 1,7-H shift process. Firstly, either heating triene 16, derived from γ-substituted allenamide 15, or 15 led to no observable 1,7-H shift with cyclic diene 19 as the only identifiable product. Isolation of 19 implies the ring-closure of triene 16 had taken place to give 18 followed by 1,5-H shift [Scheme 4]. This experiment suggests that there exists a directional preference for the 1,7-H shift in these amido-trienes, and that it is not sufficient simply having a methyl group [in red] at one terminus of the triene syn to the other terminus [in blue].

Scheme 4.

A Directional Preference in the 1,7-H Shift.

Secondly, we found a distinct dependence of the 1,7-H shift on the olefinic geometry. As shown in Scheme 5, reactions of allenamides 20-Z and 20-E proceeded through distinctly different tandem pathways. While 1,3-H–1,7-H shift occurred with 20-Z en route to cyclic amido-diene 22 via pericyclic ring-closure of triene 21, the reaction of allenamide 20-E gave 24 with no observable 1,7-H shift. Relative stereochemistry in 22 was assigned based on a disrotatory ring-closure, while the absolute stereochemistry was assessed based on 14a. Cyclic amido-diene 24 was found as a 3:1 isomeric mixture with respect to C5, thereby implying that albeit modest and unassigned at this time,19 a rather impressive 1,6-asymmetric induction took place during the ring-closure.

Scheme 5.

A Diverging Tandem Pathway: E- vs. Z-Olefin.

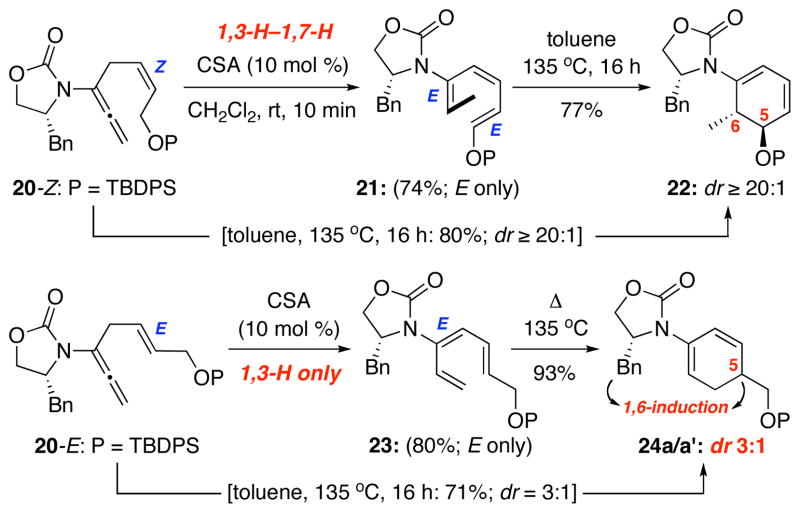

To both accentuate this dichotomy and render these stereoselective ring-closures synthetically useful, we embarked on tandem processes that would include [4 + 2] cycloadditions. As shown in Scheme 6, reactions of allenamides 25-Z and 26-Z led to tricycles 28a and 28b as a single isomer through a highly stereoselective [4 + 2] cycloaddition of cyclic amido-dienes 27a and 27b, respectively, thereby constituting a quadruple tandem process of 1,3-H-1,7-H shift–6π-electron pericyclic ring-closure–[4 + 2]-cycloaddition. Stereochemical outcome of the cycloaddition was controlled through the C5-stereocenter, which was installed during the torquos elective ring closure.

Scheme 6.

In Tandem with [4 + 2] Cycloaddition.

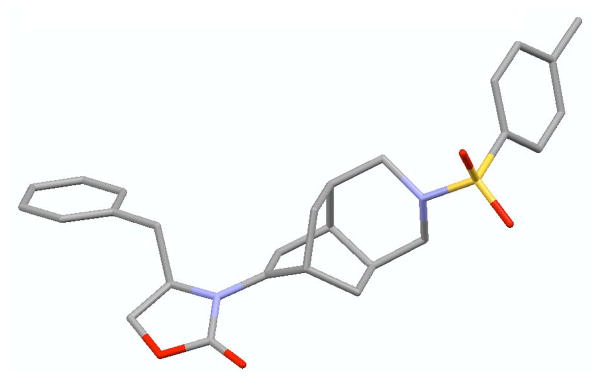

In contrast, reactions of allenamides 25-E [for a direct comparison with 25-Z] and 29-E led the respective tricycles 31a and 31b [assigned via X-ray: See Figure 2] in excellent yields and high diastereoselectivity proceeding from amido-trienes 30a and 30b or directly from the allenamides in a triple tandem process. In either case, the [4 + 2] cycloaddition presumably went through the diastereomeric pairs 32a/a′ [X = O] and 32b/b′ [X = NTs] given the modest 1,6-induction found for 20-E. It is noteworthy that despite not having assigned these diastereomers with ratios undermined,20 both pairs would actually converge to give 31a and 31b, respectively. These tandem processes provide a rapid assembly of complex tricycles from very simple allenamides, thereby manifesting their tremendous power and synthetic potential.

Figure 2.

X-Ray Structure of 31b.

We have described here a new torquoselective ring-closure of chiral amide-substituted 1,3,5-hexatrienes and its application in tandem with [4 + 2] cycloaddition. The 1,3,5-hexatrienes were derived via either a 1,3-H or 1,3-H–1,7-H shift of α-substituted allenamides, and the entire sequence through the Diels-Alder could be in tandem from allenamides. Applications of these new tandem processes as well as mechanistic understanding and improvement of the observed 1,6-asymmetric induction are underway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Authors thank NIH [GM066055] for support and Dr. Victor Young [University of Minnesota] for X-ray structural analysis.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures as well as NMR spectra, characterizations, and X-ray structural files are available for all new compounds and free of charge via Internet http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Hayashi R, Hsung RP, Feltenberger JB, Lohse AG. Org Lett. 2009;11:2125. doi: 10.1021/ol900647s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For reviews on chemistry of dienamides, see: Overman LE. Acc Chem Res. 1980;13:218.Petrzilka M. Synthesis. 1981:753.Campbell AL, Lenz GR. Synthesis. 1987:421.Also see: Krohn K. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:1582.Enders D, Meyer O. Liebigs Ann. 1996:1023.

- 3.For a review on the synthesis of enamides, see: Tracey MR, Hsung RP, Antoline J, Kurtz KCM, Shen L, Slafer BW, Zhang Y. In: Science of Synthesis, Houben-Weyl Methods of Molecular Transformations. Weinreb Steve M., editor. Chapter 21.4. Georg Thieme Verlag KG; 2005. For a leading review on recent chemistry of enamides, see: Carbery DR. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;9:3455. doi: 10.1039/b809319a.Rappoport Z. The Chemistry of Enamines in The Chemistry of Functional Groups; New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1994.

- 4.For a leading review on allenamide chemistry, see: Hsung RP, Wei LL, Xiong H. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:773. doi: 10.1021/ar030029i.

- 5.For recent reports on allenamide chemistry in 2009, see: Hashimoto K, Horino Y, Kuroda S. Heterocycles. 2010;80:187.Persson AKÅ, Johnston EV, Bäckvall JE. Org Lett. 2009;11:3817. doi: 10.1021/ol901294j.Skucas E, Zbieg JR, Krische MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5054. doi: 10.1021/ja900827p.Armstrong A, Emmerson DPG. Org Lett. 2009;11:1547. doi: 10.1021/ol900146s.Beccalli EM, Broggini G, Clerici F, Galli S, Kammerer C, Rigamonti M, Sottocornola S. Org Lett. 2009;11:1563. doi: 10.1021/ol900171g.Broggini G, Galli S, Rigamonti M, Sottocornola S, Zecchi G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1447.Lohse AG, Hsung RP. Org Lett. 2009;11:3430. doi: 10.1021/ol901283m.Lu T, Hayashi R, Hsung RP, DeKorver KA, Lohse AG, Song Z, Tang Y. Organic Biomol Chem. 2009;9:3331. doi: 10.1039/b908205k.

- 6.For general reviews on allenes, see: Krause N, Hashmi ASK. Modern Allene Chemistry. 1 and 2 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim: 2004.

- 7.For some examples of thermal allene isomerizations, see: Crandall JK, Paulson DR. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:4302.Bloch R, Perchec PL, Conia JM. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1970;9:798.Jones M, Hendrick ME, Hardie JA. J Org Chem. 1971;36:3061.Patrick TB, Haynie EC, Probat WJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971;27:423.Lehrich F, Hopf H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:2697.Meier H, Schmitt M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989:5873.

- 8.For examples of allenamide isomerizations, see: Overman LE, Clizbe LA, Freerks RL, Marlowe CKJ. Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2807.Also see. Farmer ML, Billups WE, Greenlee RB, Kurtz AN. J Org Chem. 1966;31:2885.For an allenamide isomerization via Grubb’s catalyst, see: Kinderman SS, van Maarseveen JH, Schoemaker HE, Hiemstra H, Rutjes FPJT. Org Lett. 2001;3:2045. doi: 10.1021/ol016013e.Trost BM, Stiles DT. Org Lett. 2005;7:2117. doi: 10.1021/ol050395x.

- 9.For reviews for pericyclic ring-closures, see: Marvell EN. Thermal Electrocyclic Reactions. Academic Press; New York: 1980. Okamura WH, de Lera AR. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, Fleming I, Paquette LA, editors. Vol. 5. Pergamon Press; New York: 1991. pp. 699–750.For reviews on ring-closure in natural product synthesis, see: Pindur U, Schneider GH. Chem Soc Rev. 1994:409.Beaudry CM, Malerich JP, Trauner D. Chem Rev. 2005;105:4757. doi: 10.1021/cr0406110.

- 10.For examples, see: Martínez R, Jiménez-Vázquez HA, Delgado F, Tamariz J. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:481.Wallace DJ, Klauber DJ, Chen CY, Volante RP. Org Chem. 2003;5:4749. doi: 10.1021/ol035959g.Wabnitz TC, Yu JQ, Spencer JB. Chem Eur J. 2004;10:484. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305407.

- 11.For some examples on recent 6-π-electron electrocyclic ring-closures of 1,3,5-hexatrienes, see: Bishop LM, Barbarow JE, Bergmen RG, Trauner D. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:8100. doi: 10.1002/anie.200803336.Sofiyev V, Navarro G, Trauner D. Org Lett. 2008;10:149. doi: 10.1021/ol702806v.Kan SBJ, Anderson EA. Org Lett. 2008;10:2323. doi: 10.1021/ol8007952.Hulot C, Blong G, Suffert J. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5046. doi: 10.1021/ja800691c.Benson CL, West FG. Org Lett. 2007;9:2545. doi: 10.1021/ol070924s.Pouwer RH, Schill H, Williams CM, Bernhardt PV. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:4699.Jung ME, Min S-J. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:3682.

- 12.For recent work on accelerated ring-closures of 1,3,5-hexatrienes, see: Barluenga J, Merino I, Palacios F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:6713.Magomedov NA, Ruggiero PL, Tang Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1624. doi: 10.1021/ja0399066.Tessier PE, Nguyen N, Clay MD, Fallis AG.J Am Chem Soc 2006128494616608316Huntley RJ, Funk RL. Org Lett. 2006;8:3403. doi: 10.1021/ol061259a.Yu TQ, Fu Y, Liu L, Guo QX. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6157. doi: 10.1021/jo060885i.Sunnemann HW, Banwell MG, de Meijere A. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:3879.

- 13.For theoretical studies on substituent effects on electrocyclic ring-closure of 1,3,5-hexatrienes, see: Spangler CW, Jondahl TP, Spangler B. J Org Chem. 1973;38:2478.Guner VA, Houk KN, Davies IA. J Org Chem. 2004;69:8024. doi: 10.1021/jo048540s.Yu TQ, Fu Y, Liu L, Guo GX. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6157. doi: 10.1021/jo060885i.Duncan JA, Calkins DEG, Chavarha M. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6740. doi: 10.1021/ja074402j.

- 14.(a) Trost BM, Stiles DT. Org Lett. 2005;7:2117. doi: 10.1021/ol050395x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen L, Hsung RP, Zhang Y, Antoline JE, Zhang X. Org Lett. 2005;7:3081. doi: 10.1021/ol051094q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiong H, Hsung RP, Wei LL, Berry CR, Mulder JA, Stockwell B. Org Lett. 2000;2:2869. doi: 10.1021/ol000181+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.See Supporting Information.

- 17.For recent examples in thermal antarafacial 1,7-H shift of 1,3,5-hexatrienes, see: Kerr DJ, Willis AC, Flynn BL. Org Lett. 2004;6:457. doi: 10.1021/ol035822q.Mousavipour SH, Fernández-Ramos A, Meana-Pañeda R, Martínez-Núñez E, Vázquez SA, Ríos MA. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:719. doi: 10.1021/jp0665269.Gu Z, Ma S. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:2453. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701171.Shu XZ, Ji KG, Zhao SC, Zheng ZJ, Chen J, Lu L, Liu XY, Liang YM. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:10556. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801591.

-

18.Independent heating of 13b or 14b led to no observable amount of the other compound.

- 19.Attempts were made to attain an X-ray but not successful mainly because of difficulties in the separation of diastereomers. Further efforts are ongoing.

- 20.Unfortunately, Diels-Alder cycloadditions of 32a/a′ or 32b/b′ in Scheme 6 did not provide conclusive insight into the stereochemical outcome of ring-closures of 30a and 30b.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.