Abstract

Objectives: To investigate whether intensive cognitive behaviour therapy results in significant improvement in positive psychotic symptoms in patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Design: Patients with chronic schizophrenia were randomly allocated, stratified according to severity of symptoms and sex, to intensive cognitive behaviour therapy and routine care, supportive counselling and routine care, and routine care alone.

Setting: Adjunct treatments were carried out in outpatient clinics or in the patient’s home.

Subjects: 87 patients with persistent positive symptoms who complied with medication; 72 completed treatment.

Outcome measures: Assessments of positive psychotic symptoms before treatment and 3 months after treatment. Number of patients who showed a 50% or more improvement in symptoms. Exacerbation of symptoms and rates of readmission to hospital.

Results: Significant improvements were found in the severity (F=5.42, df =2,86; P=0.006) and number (F=4.99, df=2,86; P=0.009) of positive symptoms in those treated with cognitive behaviour therapy. The supportive counselling group showed a non-significant improvement. Significantly more patients treated with cognitive behaviour therapy showed an improvement of 50% or more in their symptoms (χ2=5.18, df=1; P=0.02). Logistic regression indicated that receipt of cognitive behaviour therapy results in almost eight times greater odds (odds ratio 7.88) of showing this improvement. The group receiving routine care alone also experienced more exacerbations and days spent in hospital.

Conclusions: Cognitive behaviour therapy is a potentially useful adjunct treatment in the management of patients with chronic schizophrenia.

Key messages

Persistent psychotic symptoms are common in patients with chronic schizophrenia

Cognitive behaviour therapy is a method of changing patients’ thought processes, behaviour, and emotions

Giving cognitive behaviour therapy in addition to routine care reduced positive psychotic symptoms more than giving routine care alone

Supportive counselling was also effective but to a lesser extent

Introduction

Schizophrenia remains a debilitating disorder despite the development of drug treatments. Many patients continue to experience persistent positive psychotic symptoms, hallucinations, and delusions, which are disabling and distressing.1,2 Cognitive behavioural therapies, developed and evaluated with affective disorders, have recently been used to treat these persistent hallucinations and delusions as an adjunct to medication. Reviews of cognitive behaviour therapy in schizophrenia indicate that evaluations are mainly case studies or uncontrolled trials.3–5 Four controlled trials have suggested that cognitive behavioural interventions can result in a reduction of psychotic and associated symptoms that are resistant to medication in chronic schizophrenia,6–9 and a single trial has shown reduction of symptoms in acute schizophrenia.10 Although these trials are small and all suffer methodological limitations, particularly a lack of blind assessment, they represent encouraging evidence that cognitive behavioural interventions can have considerable benefits in reducing persistent hallucinations and delusions. If these findings prove to be robust this would be an important clinical advance as any improvement in symptoms that are resistant to medication will be of considerable benefit to that patient and in the long term may well reduce the cost of care.

In an earlier open trial two cognitive behavioural treatments—coping strategy enhancement and problem solving—were compared. Both interventions were associated with significant reductions in positive psychotic symptoms.6 This paper reports on the initial results of a larger randomised controlled trial of intensive cognitive behaviour therapy as an adjunct to routine care, including stable prophylactic medication, in the treatment of chronic schizophrenia. In this trial cognitive behaviour therapy was more intensive in nature than had been used in the past and combined training in coping and problem solving skills with prevention of relapse. To control for the non-specific factors of therapy we compared outcome with outcome in a group receiving supportive counselling in addition to routine care. The following hypotheses were tested: that the cognitive behaviour therapy would be superior to supportive counselling and routine care, and routine care alone, firstly, in reducing positive psychotic symptoms; secondly, in preventing the exacerbation of positive symptoms and reducing hospital stay; and, thirdly, by using the convention of the previous study of 50% improvement in positive symptoms as an indicator of considerable clinical improvement,6 in the number of patients achieving such improvement.

Methods

Procedure

Potentially eligible patients were identified through hospital and clinic databases in three NHS trusts in Greater Manchester, which represented together a geographical cohort from a catchment area of 508 049 people (1994 census). The case notes of these patients were then screened, and the responsible medical officer was approached to give permission for the assessment of those meeting the inclusion criteria at this stage. Patients were then approached to give informed consent and, if they gave consent, were interviewed to confirm entry criteria and provide baseline assessments. Patients had to fulfil the following criteria: a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective psychosis, or delusional disorder according to criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition, revised11; no evidence of organic brain disease; substance abuse not identified as the primary problem; age between 18 and 65 years; presence of persistent hallucinations or delusions, or both, for a minimum of 6 months and at least 1 month of stabilisation if they had experienced an exacerbation during this period; stable medication; no psychological or family intervention; their responsible medical officer had given permission for them to enter the study; no serious threat of violence towards the assessors; and they had given informed consent to participate. Patients so recruited were assessed on baseline measures. After assessment patients were allocated on a stratified block randomised procedure with block size equal to nine by using severity of symptoms (determined by a total psychiatric assessment scale score; ⩽12 low severity, ⩾13 high severity)12 and sex to one of three treatment groups: cognitive behavioural therapy plus routine care; supportive counselling plus routine care; and routine care alone. Allocation, contained in sealed envelopes, was carried out independently by a third party.

We estimated that a sample size of 28 in each group would have 80% power to detect a difference of 1.2 or more between the groups in the change (before and after treatment) of the number of positive symptoms, with a common SD of 1.5 and the conventional 5% significance level. This difference is equivalent to 25% of the number of positive symptoms at baseline.

Assessments

Standardised measures were used to assess positive psychotic symptoms as the primary outcome measure. Assessments were carried out at baseline before treatment and at 3 months. Positive psychotic symptoms, hallucinations, and delusions were elicited by the present state examination13 and each individually rated on the brief psychiatric rating scale (0 to 6) for hallucinations or unusual thought content.14 This allowed a score of the number of symptoms experienced by each individual by summing all the categories of affirmed delusional and hallucination symptoms on the present state examination schedule (for example, if the patient experienced hearing voices talking about and to him or her—symptoms 62 and 63 on the present state examination—this would be scored as 2) and a score of the total severity of symptoms by aggregating the scores on the 7 point scales for all the symptoms experienced by each individual.

Effort was made to blind the independent assessors to treatment allocation by using separate offices in a different part of the hospital for the assessors and therapists, using separate administrative procedures, instructing patients to not reveal details of their care, data entry being carried out independently of the assessors, and using a multiple coding system for treatment groups. At the completion of the study assessors were asked to guess the group allocation of each patient. They were not aware that they would be asked to do this so as not to prime them to the task. Comparison with actual allocation indicated that guesses were not significantly better than chance, suggesting that blinding was satisfactory.

Basic demographic information and details of psychiatric history, medication (converted to chlorpromazine equivalents15), and inpatient stays during the trial were recorded.

Treatment groups

Intensive cognitive behaviour therapy plus routine care

—This intervention had three components: coping strategy enhancement, aimed at teaching patients specific methods of coping with their symptoms; training in problem solving; and strategies to reduce risk of relapse. The three components consisted of six hourly sessions each followed by two summary sessions. Sessions were carried out twice a week and 20 sessions of treatment were carried out over 10 weeks. Details of the treatment are provided elsewhere.3,6

Supportive counselling plus routine care

—This intervention aimed to provide emotional support through the development of a supportive relationship fostering rapport and unconditional regard for the patient. General counselling skills were used to maximise the non-specific effects of intervention. Supportive counselling followed an identical format to the cognitive behaviour therapy intervention—20 sessions of 1 hour twice a week. Forty two (71%) patients receiving cognitive behaviour therapy or supportive counselling were treated in outpatient clinics, and 17 in their homes.

Routine care

—Routine care consisted of standard psychiatric management by the clinical team with medication and monitoring outpatient follow up and the care programme approach.

Fidelity of treatment

Therapy was performed by three experienced clinical psychologists and followed a protocol manual, and the three therapists met on a regular basis to discuss cases. An ad hoc selection of cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive counselling sessions were audiotaped and rated by an independent rater as either cognitive behaviour therapy or supportive counselling. Cognitive behaviour therapy was further assessed as coping strategy enhancement, training in problem solving, or prevention of relapse. Twenty two sessions were cognitive behaviour therapy (13 coping training, 6 problem solving, and 3 response prevention) and 12 were supportive counselling sessions.

Statistical analysis

Results were analysed with spss for Windows (version 6.1) and in consultation with the statistics unit at Withington Hospital. Differences between the three treatment groups were assessed with χ2, one factor analysis of variance, and the Kruskal-Wallis test when appropriate. A logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables having a significant independent association with an improvement of 50% or more in positive psychotic symptoms. Tests of skewness and normality for clinical variables were acceptable. There were no clinically significant differences between treatment groups before the study.

Results

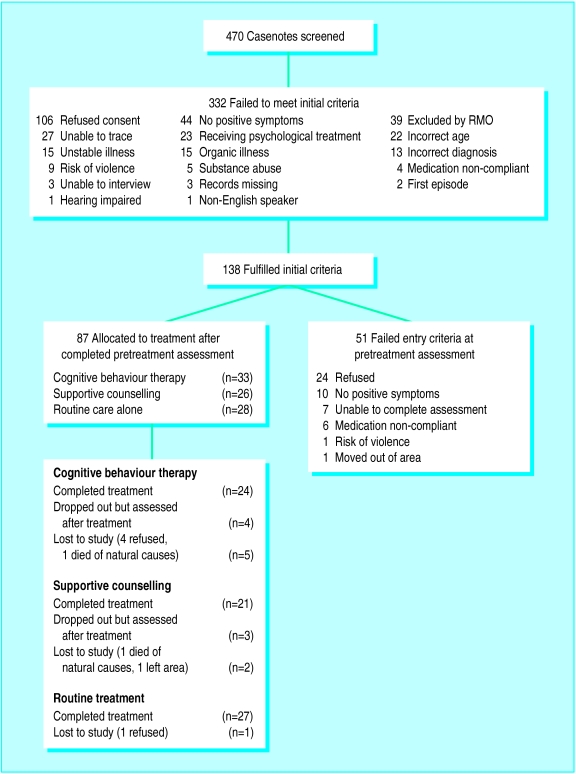

Details of recruitment are presented in the figure. Eighty seven patients fulfilled entry criteria and completed assessment before treatment. Of these, 72 who completed treatment and seven who dropped out of treatment completed assessment after treatment, resulting in a total sample of 79 for whom complete data were available. In the remaining eight the last available scores were carried forward.

Patient characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 87 patients were as follows: mean age 38.6 (SD 11.0) years; 69 men; 64 single; 24 lived alone, 17 lived with a partner, 31 lived with parents, and the remainder with others; 61 left school at 16 years; 76 were unemployed, five were in paid employment, six were in voluntary employment or similar, two had never worked; 64 were unskilled and 21 were skilled or professional; 78 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, eight had schizoaffective psychosis, and two had delusional disorder; the median (range) duration of illness was 11 (1-42) years; median (range) number of admissions to hospital was 3 (0-20); 10 had a forensic psychiatric history; and 12 had a history of substance abuse.

Fidelity of treatment

Correct classification was made on 33 of the 34 taped sessions (97% agreement), with one early coping session being misclassified as “borderline” supportive counselling. This level of discrimination between cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive counselling is highly satisfactory and indicates with a high degree of confidence that these treatments followed protocol.

Medication

Doses of drugs over the trial were converted to mean daily equivalents of chlorpromazine and compared across groups by means of Kruskal-Wallis one way analysis of variance; this indicated no significant differences between treatment groups (medians of daily drugs in chlorpromazine equivalents: cognitive behaviour therapy 425, supportive counselling 517.75, routine care 450; χ2=0.963; P=0.62). Nine patients were taking atypical neuroleptic drugs (clozapine or risperidone) during the duration of treatment (two in the cognitive behaviour therapy group, four in the supportive counselling group, and three in the routine care group). Thus there was no evidence of systematic and significant differences between the groups in terms of medication.

Comparisons of efficacy of treatment groups

The relative efficacy of the treatment groups was analysed by means of one way analysis of variance on the changes in scores before and after treatment. Relevant changes and confidence intervals are presented in the table. A post hoc test (Tukey-HSD) indicated the location of any significant differences at the 0.05 level between pairs of comparisons. Analysis by intention to treat was completed on the 87 allocated patients, with last observations (scores before treatment) being carried forward for the eight patients for whom scores after treatment were missing.

Significant effects were found for the number of positive psychotic symptoms a patient experienced, and their severity. The cognitive behaviour therapy group showed a greater improvement than the supportive counselling group and patients in the routine care group showed a slight deterioration (table).

Clinically important improvement

Eighteen subjects achieved 50% improvement in psychotic symptoms in both severity and number of symptoms, taken as representing an important clinical improvement. Eleven (of 33) were in the cognitive behaviour therapy group, four (of 26) in the supportive counselling group, and three (of 28) in the routine care group. This difference was significant when the number of patients who showed a 50% or greater improvement was compared between those who received cognitive behaviour therapy and the other two groups combined (χ2=5.18; df=1; P=0.02). Five patients who received cognitive behaviour therapy and two who received supportive counselling were free from all positive symptoms after treatment, whereas none who received routine care alone achieved this.

Because an improvement of 50% or more in psychotic symptoms represents such an important clinical change in patients with chronic schizophrenia a logistic regression was performed to investigate which variables contributed to this improvement. Treatment group was represented as a categorical variable having three levels in the analysis, with routine care acting as the reference category. Three variables showed a significant contribution: allocation to cognitive behaviour therapy (B 2.064; SE 0.726; P=0.0045; Exp(B) 7.878); duration of illness (B −0.144; SE 0.054; P=0.0079; Exp(B) 0.866); severity of symptoms on the psychiatric assessment scale (B −1.893; SE 0.815; P=0.02; Exp(B) 0.151). Thus receipt of cognitive behaviour therapy resulted in almost eight times greater odds of showing a reduction in psychotic symptoms of 50% or more than subjects receiving routine care alone. A shorter duration of illness and less severe symptoms at allocation also significantly contributed to this outcome. The odds of subjects showing a reduction in psychotic symptoms of 50% or more decreased by a multiplication factor of 0.87 for every additional year of duration of illness, and decreased by a multiplication factor of 0.15 for every unit increase in severity of illness.

Relapse and readmission to hospital

The hypothesis that cognitive behaviour therapy would result in a reduction in subsequent relapse is more speculative as patients were recruited and treated during the residual phase of the disorder and there will be varying times since the patient’s previous acute episode and in their vulnerabilities to relapse. Furthermore, relapse in terms of exacerbation of positive symptoms is difficult to assess accurately as all patients were symptomatic. Thus readmission to hospital for clinical deterioration that resulted in functional impairment and admission for at least 5 days, although not an ideal measure, was chosen as a practical indicator of relapse.

Eighty five patients were followed up from the original 87, two having died of natural causes. From before to after treatment (3 months) there were no relapses in either cognitive behaviour therapy or supportive counselling groups and four (14%) in the routine care group. The total number of days spent in hospital for patients in the routine care group was 204, whereas one patient from both the cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive counselling groups spent 1 day in hospital.

Discussion

Patients receiving cognitive behaviour therapy showed the greatest improvement in positive symptoms. Patients receiving routine care alone showed minimal change, and those who received supportive counselling showed some improvement but less so than those receiving cognitive behaviour therapy. This difference was significant for cognitive behaviour therapy compared with routine care alone.

As in the earlier study6 a considerable number of patients showed a reduction in their positive symptoms of 50% or more, which is a considerable clinical improvement, and analysis indicated that receiving cognitive behaviour therapy increased the probability of this reduction by nearly eight times. During the 3 month period both cognitive behaviour therapy and supportive counselling seemed to buffer against relapse. Patients in the routine care group spent much more time in hospital compared with patients in the other two groups (204 days compared with 1), which will probably have cost implications.

Medication was not controlled for in the study. It was not possible for the research team to administer medication or take over clinical responsibility for the study patients. It is also doubtful from a methodological point of view whether this would have been advantageous. Medication is clearly an important factor in recovery, and the impact of medication on outcome was reduced by excluding patients who were not compliant or on stable regimens. Retrospective analysis of medication indicated that there were no systematic differences in medication that could explain the differences in outcomes between the treatment groups.

The data suggest that there is considerable variation in how patients respond to treatment, with overlap between the groups. This is not surprising considering the nature and severity of schizophrenia. Cognitive behaviour therapy as used here is an adjunct treatment which is being given alongside routine management and prophylactic medication to assess whether there is added value of this combination. We made no attempts to select patients and the positive effects of cognitive behaviour therapy could be enhanced by being able to identify which patients would be most responsive to adjunct psychological treatment. What is perhaps unexpected is that supportive counselling achieved an intermediary position between cognitive behaviour therapy and routine care alone, suggesting that non-specific psychological effects—such as intensive interest and support—can have a beneficial effect for patients with chronic psychosis. We tentatively conclude that cognitive behaviour therapy, used as an adjunct treatment for chronic schizophrenia, can result in clinical benefits in the short term.

Figure.

Recruitment and allocation of subjects

Table.

Mean (SD) baseline scores and mean change (95% confidence intervals) according to treatment for chronic schizophrenia. Negative changes indicate improvement

| Detail | Cognitive behaviour therapy

|

Supportive counselling

|

Routine care alone

|

F value | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change after treatment | Baseline | Change after treatment | Baseline | Change after treatment | |||||

| No of symptoms | 4.46 (3.5) | −1.6 (−2.5 to −0.7) | 4.79 (3.3) | −0.5 (−1.2 to 0.2) | 4.78 (3.4) | 0.11 (−0.7 to 0.9) | 4.99 (df=2,86) | 0.009 | ||

| Severity of symptoms | 20.0 (16.5) | −7.8 (−12.0 to −3.8) | 23.0 (16.8) | −3.9 (−6.9 to −0.9) | 21.2 (15.3) | 0.07 (−3.1 to 3.3) | 5.42; (df=2,86) | 0.006 | ||

Acknowledgments

We thank J S Bamrah, Angela Connor, and Abi James for their assistance in the project and Til Wykes and Christine Barrowclough for their comments on an earlier copy of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: This research was supported through a project grant from The Wellcome Trust awarded to the first author.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Curson D, Barnes T, Bamber R, Platt S, Hirsch S, Duffy J. Long-term depot maintenance of chronic schizophrenic outpatients. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;146:464–480. doi: 10.1192/bjp.146.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falloon I. Cognitive and behavioural interventions in the self-control of schizophrenia. In: Strauss J, Boker W, Brenner H, editors. Psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. Bern: Hans Huber; 1986. pp. 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarrier N. Psychological treatment of positive schizophrenic symptoms. In: Kavanagh D, editor. Schizophrenia: an overview and practical handbook. London: Chapman and Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddock G, Sellwood W, Tarrier N, Yusupoff L. Developments in cognitive behaviour therapy for persistent psychotic symptoms. Beh Change. 1994;11:200–214. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddock G, Tarrier N, Spauldin, W, Yusupoff L, Kinney C, McCarthy E. Individual cognitive-behavior therapy in the treatment of hallucinations and delusions: a review. Clin Psychol Rev (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Tarrier N, Beckett R, Harwood S, Baker A, Yusupoff L, Ugarteburu I. A trial of two cognitive-behavioural methods of treating drug-resistant residual psychotic symptoms in schizophrenic patients. I: Outcome. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:524–532. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garety P, Kuipers L, Fowler D, Chamberlein F, Dunn G. Cognitive behavioural therapy for drug resistant psychosis. Br J Med Psychol. 1994;67:259–271. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1994.tb01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haddock G, Bentall R, Slade P. Psychological treatment of auditory hallucinations: focusing or distraction? In: Haddock G, Slade P, editors. Cognitive behavioural interventions with psychotic disorders. London: Routledge; 1996. pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuipers E, Garety P, Fowler D, Dunn G, Bebbington P, Freeman D, et al. The London-East Anglia randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis: effects of the treatment phase. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:319–325. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drury V, Birchwood M, Cochrane R, Macmillan F. Cognitive therapy and recovery from acute psychosis. I: Impact on symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;169:593–601. doi: 10.1192/bjp.169.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krawieka M, Goldberg D, Vaughan M. A standardised psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1977;55:299–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wing J, Cooper J, Sartorius N. Measurement and classification of psychiatric symptoms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukoff D, Liberman R, Nuechterlein K. Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1986;12:578–603. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organisation. Anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification index including defined daily doses (DDDs) per plan substance. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics and Methodology; 1994. [Google Scholar]