Abstract

In Pavlovian fear conditioning animals receive pairings of a neutral cue and an aversive stimulus such as an electric foot-shock. Through such pairings, the cue will come to elicit a central state of fear that produces a variety of autonomic and behavioral responses, among which are conditioned freezing and suppression of instrumental responding, termed conditioned suppression. The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) and the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG) have been strongly implicated in the acquisition and expression of conditioned fear. However, previous work suggests different roles for the CeA and vlPAG in fear learning may be revealed when fear is assessed with conditioned freezing or conditioned suppression. To further explore this possibility we gave rats selective lesions of either the CeA or vlPAG and trained them in Pavlovian first-order fear conditioning as well as Pavlovian second-order fear conditioning. We concurrently assessed the acquisition of conditioned freezing and conditioned suppression. We found that vlPAG and CeA lesions impaired both first- and second-order conditioned freezing. VlPAG lesions did not impair, and CeA lesions only transiently impaired, first-order conditioned suppression. However, both vlPAG and CeA lesions impaired second-order conditioned suppression. These results suggest that the CeA and vlPAG are critically important to expressing fear through conditioned freezing but play different and less critical roles in expressing fear through conditioned suppression.

Keywords: second-order, associative, conditioned suppression, aversive

Introduction

In Pavlovian fear conditioning, animals receive pairings of a neutral cue and an aversive stimulus such as an electric foot-shock. When arranged in this manner the cue becomes a conditioned stimulus (CS) and acquires the ability to elicit a central state often described as ‘fear.’ This central state of fear is manifested in a number of behavioral [1] and autonomic [2, 3] responses, one of which is freezing [4]. Additionally, the central fear state elicited by the CS can allow it to substitute for the foot-shock in some ways. In Pavlovian second-order conditioning a novel second-order cue (SOCS) predicts delivery of the CS. As a result of this arrangement the SOCS will come to elicit freezing [5].

When a CS is superimposed over a baseline of instrumental responding for rewarding outcomes there is a strong suppression of responding, termed first-order conditioned suppression [6]. Although many possible behavioral mechanisms may contribute, first-order conditioned suppression is commonly described as a byproduct of freezing. Rats that are immobile are unable to make instrumental responses. Supporting this, previous studies have found that first-order conditioned suppression was accompanied by freezing, with more freezing associated with more suppression [7, 8]. A SOCS will also suppress instrumental responding [9].

The central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA) is thought to play a role in either producing the central state of fear [10] or serving as the final node of common pathway for conditioned fear responses. The ventrolateral periaqueductal grey (vlPAG) is typically described as being responsible for expressing this fear through freezing [11]. Supporting this view, lesions or pharmacological manipulations of the CeA [10, 12–15] or vlPAG [11, 16–18] impair the normal acquisition and/or expression of conditioned freezing. If conditioned suppression is largely an indirect measure of conditioned freezing, then impairments in first- and second-order conditioned freezing resulting from CeA or vlPAG lesions should be reflected in first- and second-order conditioned suppression.

In the present experiment rats with either selective, neurotoxic CeA lesions or electrolytic vlPAG lesions received Pavlovian fear conditioning in which one visual CS+ predicted foot-shock while a second, CS− did not. Second-order conditioning was then given in which one auditory SOCS+ predicted the CS+ while a different auditory SOCS− predicted the CS−. Freezing and instrumental suppression were measured concurrently to determine whether there were differential effects of CeA or vlPAG lesions on the two measures. We found that both lesions affected first- and second-order conditioned freezing, while lesions impaired second-, but not first-order conditioned suppression. These results suggest that the CeA and vlPAG are critically important to expressing fear through freezing but play different and less critical roles in expressing fear through conditioned suppression.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The subjects were 32 male Long-Evans rats (Charles River Laboratory, Raleigh, NC, USA) housed in individual cages under a 12h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 AM). After arrival, rats were given ad libitum access to food for one week and then placed on food deprivation until reaching 85% of their initial, free feeding body weight and then maintained at that level. Rats had free access to water in their home cage for the duration of the experiment. The following week rats received instrumental training after which they were returned to ad libitum food access and given neurotoxic lesions of the CeA (n=11), electrolytic lesions of the vlPAG (n=11), sham CeA lesions (n=5) or sham vlPAG lesions (n=5). No behavioral differences were observed between sham CeA and sham vlPAG lesions, these groups were subsequently analyzed together (n=10). A postoperative recovery interval of about two weeks occurred before behavioral procedures resumed. To account for weight gained during the surgery period, 5% of their post-surgical weight was added to their original 85% weight. Rats were deprived and then maintained at that 85% weight for the remainder of the experiment. All experiments were conducted according to the NIH guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the protocols were approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

The behavioral training apparatus consisted of four individual chambers (22.9 × 20.3 × 20.3 cm) with aluminum front and back walls, clear acrylic sides and top, and a floor made of 0.48-cm stainless steel rods spaced 1.9 cm apart. The steel rods were connected to a shock generator (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA) capable of delivering scrambled shock over a range of intensities. A dimly illuminated food cup was recessed in the center of one end wall. To the left of the recessed food cup a retractable lever 1.5 cm wide protruded from the wall. Each chamber was enclosed in a sound-resistant shell. A speaker, used to present auditory CSs, was mounted on the inside wall of the inner shell, 10 cm above the experimental chamber and level with the end wall opposite the food cup. A 6-W lamp was mounted behind a jeweled lens on the front panel, 10 cm above the food cup; illumination of this lamp served as one CS. A second light mounted to the rear wall served as the second CS. Ventilation fans provided masking noise (70 dB). A 6-W lamp behind a dense red lens, mounted next to the speaker, provided constant dim illumination. A TV camera was mounted within each shell to provide a view of the chamber; the output from each camera was digitized, merged into a single image of all four chambers and recorded on videotape.

Surgery

All surgeries were performed under aseptic conditions using isoflurane gas for induction and maintenance of anesthesia, using a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Neurotoxic, bilateral lesions of CeA were made with a 2.0 µl Hamilton syringe using ibotenic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution. Ibotenic acid was chosen because it has been commonly used to produce selective CeA lesions in experiments using Pavlovian appetitive conditioning as well as Pavlovian fear conditioning [14, 19]. Each CeA rat received one injection in each hemisphere. Injection sites were 2.4 mm posterior to bregma and 4.3 mm lateral from the midline. Ibotenic acid (0.25 µl) was injected over 2.5 min, 8.0 mm ventral to the skull surface. Electrolytic, bilateral vlPAG lesions were made with a stimulating electrode. Electrolytic lesions were chosen for comparison with results from other studies that used these methods to lesion the ventrolateral portion of the PAG to decrease conditioned freezing [11, 16, 17]. Lesions sites were 7.7 mm posterior to bregma and 0.7 mm lateral from the midline. A 1 mA current was delivered over 10 s, 6.5 mm ventral to the skull surface. Sham CeA lesions (n = 5) and sham vlPAG lesions (n = 5) were made using the same coordinates as neurotoxic and electrolytic lesions, only no solution or current was delivered. After surgery, all rats received a single subcutaneous injection of 0.01 mg/kg buprenorphine hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for amelioration of pain.

Pavlovian fear conditioning

To become familiar with eating from the food cup, rats were placed in the experimental chamber where 30, 45-mg food pellets (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) were delivered over the course of 30 min (mean pre-CS - 1 min). In the following three sessions the lever was introduced and reinforced on a continuous basis (1 lever press = 1 pellet). Rats remained in the experimental chamber until 50 presses were reached or 30 min expired. Those that failed to reach 50 responses in 30 min received additional training sessions. Following lever press acquisition rats were placed on a variable interval 30-s (vi30) schedule of reinforcement for 60 min sessions, in which lever presses were rewarded every 30 s on average. After two sessions a vi60 schedule was put in place and finally a vi90 schedule was implemented. For the remainder of the experiment the lever was always present and reinforced on a vi90 schedule. All sessions were 60 min. Following instrumental acquisition, rats were assigned to groups, equating for body weight and lever-press rate, and given lesions (see above).

Subsequent to recovery from surgery all rats were given at least one additional session of instrumental training to ensure that vi90 responding was stable. In order to overcome unconditioned suppression to the visual cues, three sessions of pretesting were administered during which the 20-s intermittent panel light and the 20-s constant house light were each presented four times. The first three sessions of conditioned suppression were composed of CS+ trials only. The panel light served as CS+ for half of the rats in each group, while the house light was the CS+ for the remaining half. CS+ trials began with a 20-s empty period followed by 20-s CS presentation and terminating with electric foot-shock delivery (1 mA, 0.5 s) which was delivered at light offset (A pilot experiment found this intensity and duration of shock was the minimum necessary to produce significant first- and second-order conditioning). Only two CS+ trials occurred on these sessions (mean pre-CS - 20 min). The final twelve sessions consisted of discrimination learning with each session consisting of two CS+ and six CS− trials (mean ITI – 6 min). The CS− for each rat was the visual cue not used as CS+. CS− trials occurred exactly as CS+ trials, only no shock was administered.

Second-order conditioning

In second-order discrimination, one auditory cue predicted the occurrence of one visual cue. Auditory cues were a 30-s constant tone and 30-s white noise. For example, if the tone predicted the panel light, and the panel light was the CS+, then the tone became the second-order CS+ (SOCS+). In this case the noise would serve as the SOCS−, predicting the house light (CS−). The pre-SOCS period was also 30 s. The identity of the auditory cues was fully counterbalanced so that for half of the rats in each group tone was the SOCS+ while noise was the SOCS−. The converse was true for the remaining half. On the first session of second-order conditioning four SOCS+ and four SOCS− trials were administered in which a 30-s auditory cue was immediately followed by a 20-s visual cue. No foot-shocks were presented on SOCS+ trials. Beginning on session two and continuing through the remainder of conditioning three SOCS+ and three SOCS− trials were given. In these sessions one CS+ (CS+ paired with shock) and one CS− (CS− with no shock) were also presented. This was done to ensure the first-order cue did not extinguish.

Behavioral measures

Lever-press rate and freezing were sampled on every trial, providing two indices of conditioning. Lever responses were recorded automatically during pre-CS, CS+ and CS− for all trials. Pavlovian fear conditioning sessions were recorded on videotape and scored for freezing. Freezing was defined as the absence of movement accompanied by a stiff, rigid posture. To be counted as freezing, all forelimbs had to remain on the floor. Head movements that did not interfere with the stiff posture were also counted as freezing. These head movements mostly consisted of slow scanning back and forth. While not quantified, hyperventilation and piloerection were also used as evidence that the rat was freezing and not merely quiescent. Whisker movements or sniffing while in the stiff posture did not count as freezing. Rat’s behavior was sampled at 1.25-s intervals during pre-CS, CS+ and CS− periods. During each sample the rat was determined to either be freezing or not freezing. Percent time freezing for both CS+ and CS− was calculated by dividing the number of instances of freezing by the number of samples of freezing and multiplying by 100.

Histological procedures

After completion of the behavioral procedures, rats were anesthetized and perfused with 0.9% saline. Sham and CeA rats were then perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 PB while sham and electrolytic vlPAG rats were perfused with 4% formalin. Brains were removed, postfixed overnight in the same solution used for perfusion plus 12% sucrose, and frozen the next day for storage at −80°C. Brains were sliced on a freezing microtome and 40 µm coronal sections through CeA and vlPAG were collected in four series. One series from each brain was mounted and Nissl stained. For CeA lesions, a second series was mounted and stained with gold III chloride (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to determine the damage to fibers of passage.

Statistics

Behavioral data were analyzed with Statistica (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) using ANOVA. Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s were used when appropriate. In all cases p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Histology

Using the Nissl series, six of eleven CeA rats were determined to have acceptable neurotoxic lesions (see Fig. 1A–F). The region of interest in lesion analysis was the medial central nucleus at bregma −1.40, −2.12 and −2.56 [20]. Acceptable lesions had damage to at least 50% of the total area of medial CeA in each subject. Damage must have been exclusively neurotoxic with no observable damage to fibers of passage. Average lesion size was 68.1 ± 5.4% (sem) of medial CeA and broke down as follows: bregma −1.40: 53.3 ± 16.9%; −2.12: 87.2 ± 8.0%; −2.56: 67.4 ± 15.2%. Fibers of passage through the CeA were verified to be intact (Fig. 1E, F) ensuring that any behavioral effects were the result of a neurotoxic lesion. Damage to the basolateral amygdala (BLA) was quantified at the same three bregma levels, as well as bregma −3.14. On average, 13.4 ± 4.3% of the BLA was damaged across rats. Greater damage was seen in the anterior levels where 19.8 ± 9.1% of the total area was lesioned. Damage was less evident in the posterior BLA where 10.8% ± 2.4% of BLA was damaged. (Note that the overall BLA damage is not the average of the anterior and posterior levels because there is more area in the posterior levels.) There was no observable damage in Sham CeA lesioned rats (Fig. 1A, C, E).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs show representative Nissl sections of (A) Sham and (B) Neurotoxic lesions the CeA at Swanson level 26 (−2.12 mm posterior from bregma). High magnification images centered on medial CeA for (C) Sham and (D) Neurotoxic lesions are also shown. Note in (C) the abundance of healthy cells with little sign of gliosis and contrast with (D) where the number of healthy cells as decreased and gliosis (small black specks) is apparent. Finally, fiber staining for (E) Sham and (F) Neurotoxic CeA lesions is shown. For all acceptable lesions there was no damage to fibers of passage through CeA.

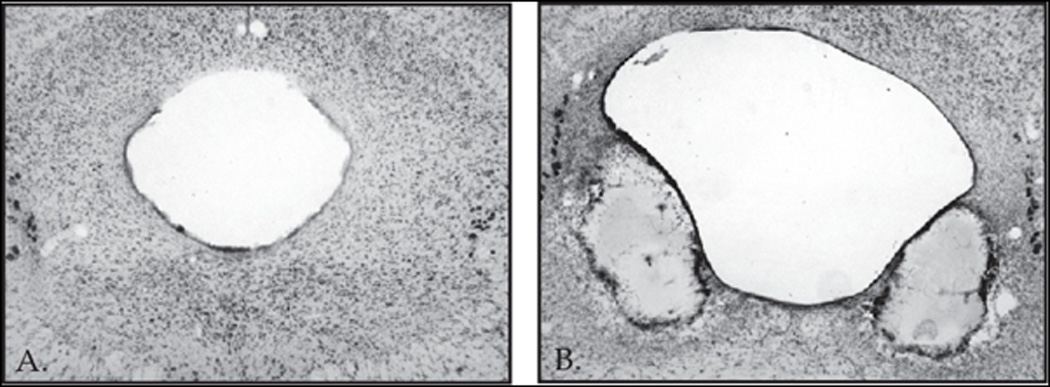

Two vlPAG rats died immediately following surgery. Seven of the remaining nine rats were judged to have acceptable and selective vlPAG lesions (see Fig. 2A, B). VlPAG damage was quantified at bregma −7.80, −8.30 and −8.72. To be considered acceptable rats had to have damage to at least 40% of the vlPAG. Average vlPAG lesion size was 54.3 ± 4.1% and broke down as follows: −7.80: 73.7 ± 8.1%; −8.30: 56.9 ± 6.8%; and −8.72: 37.8 ± 9.5%. In order to address selectivity of vlPAG lesions, damage to the lateral PAG (lPAG) and dorsolateral PAG (dlPAG) were quantified. Average lPAG lesion size was 22.8 ± 4.5% and dlPAG lesion size was 9.6 ± 7.0%. Thus, damage was mostly confined to the ventrolateral portion of the periaqueductal grey (Fig. 2B). There was no observable damage in Sham vlPAG lesioned rats (see Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs show representative Nissl sections of (A) Sham and (B) Electrolytic lesions the vlPAG at Swanson level 51 (−8.30 mm posterior from bregma). Note the extensive damage ventrolateral to the periaqueductal grey and the enlargement of the central aqueduct.

Behavioral results

First-order conditioned freezing

Sham rats showed excellent acquisition of and discrimination in first-order conditioned freezing. VlPAG rats acquired freezing to the CS+ but failed to discriminate between CS+ and CS− while CeA rats were impaired in both acquisition and discrimination (see Fig. 3A–C). There was no effect of lesion (p > 0.1) nor was there a session × lesion interaction (p > 0.1) on pre-CS freezing. Repeated measures ANOVA for CS+ freezing (Fig. 3A–C) in the three lesions groups over all sessions of first-order conditioning found significant effects of lesion (F(2,20) = 5.10, p < 0.05) and session (F(8,160) = 13.30, p < 0.01). Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s HSD demonstrated that Sham rats showed significantly more freezing than CeA rats (p < 0.05) but not vlPAG rats (p > 0.1). CS+ freezing between CeA and vlPAG did not differ (p > 0.1).

Figure 3.

Freezing and instrumental suppression in first-order Pavlovian fear conditioning. (A–C) Mean (± SEM) % time freezing during CS+ (closed shapes) and CS− (open shapes) over the course of first-order Pavlovian fear conditioning. (D–F) Mean (± SEM) lever-press rates during CS+ and CS− from the same sessions. Data points 1–3 are CS+ only sessions; 4–9 are two-session blocks of first-order discrimination. Sham (circles), vlPAG (triangles) and CeA (diamonds) rats are shown in three separate columns.

Initially the CS− also elicited robust freezing in Sham rats though robust discrimination was observed by the final block. VlPAG and CeA rats did not demonstrate significant discrimination (Fig. 3A–C). Repeated measures ANOVA for CS+ and CS−freezing in the final block of conditioning revealed significant effects of cue (F(1,20) = 37.17, p < 0.01) as well as the cue × lesion interaction (F(1,20) = 4.11, p < 0.05). Post-hoc comparisons found that sham rats froze significantly more during CS+ than CS− (p < 0.01) while vlPAG and CeA rats failed to discriminate (p >0.1).

First-order conditioned suppression

In contrast to the effects of lesions on conditioned freezing, vlPAG rats showed excellent discrimination in first-order conditioned suppression, and CeA rats were able to acquire full suppression to the CS+ and discriminate between CS+ and CS− at levels identical to Shams (see Fig. 3D–F). There was no effect of lesion (p > 0.1) nor was there a session × lesion interaction (p > 0.1) on pre-CS lever-press rates (Sham: 8.5 ± 1.73; vlPAG: 8.0 ± 1.73; and CeA: 9.0 ± 2.36). Repeated measures ANOVA for CS+ lever-press rate over all sessions of conditioning was performed with lesion and session as factors. Significant effects of lesion (F(2,20) = 5.08, p < 0.05), session (F(8,160) = 39.09, p < 0.01) and the lesion × session interaction (F(16,160) = 3.02, p < 0.01) were observed. Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s HSD revealed that Sham and vlPAG rats showed identical levels of CS+ lever pressing over the course of conditioning (p > 0.1). Sham rats differed from CeA (p < 0.05) as did vlPAG rats (p < 0.05). However, no differences in CS+ lever-press rates were observed when only the final block of conditioning was analyzed (p > 0.1). CeA rats were initially impaired in conditioned suppression but overcame this deficit by the end of training.

Initially the CS− also elicited suppression in Sham rats, though robust discrimination was observed by the final block. Repeated measures ANOVA for CS+ and CS− lever-press rate (see Fig. 3D–F) in the final block of conditioning was performed. In contrast to freezing, only a significant effect of cue (F(1,20) = 55.92 p < 0.01) was found; there was no cue × lesion interaction (F(2,20) = 0.006 p > 0.1). As expected, post-hoc comparisons found that all groups suppress lever-pressing significantly more during CS+ compared to CS− (p < 0.01 in all cases).

Second-order conditioned freezing

Sham rats showed an identical pattern of freezing to the CS+ and CS− that followed the SOCS+ and SOCS− in second-order conditioning as they did to the CS+ and CS− at the end of first-order conditioning. The impairment of vlPAG and CeA rats in discriminative freezing during first-order conditioning was also present in second-order conditioning (see Table 1). Repeated measures ANOVA was performed comparing freezing in the final block of first-order conditioning to CS+ and CS− freezing that followed the SOCS+ and SOCS− over the five sessions of second-order conditioning. Significant effects of cue (F(3,60) = 28.15 p < 0.01) and the cue × lesion interaction (F(6,60) = 2.77 p < 0.05) were observed. Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s HSD revealed that Sham, vlPAG and CeA rats froze at identical levels to the CS+ in first- and second-order conditioning (p > 0.1 in all cases). The same was true of CS− freezing (p > 0.1 in all cases). Importantly, and like in first-order conditioning, Sham rats showed excellent discriminative freezing between CS+ and CS− following the SOCS+ and SOCS− (p < 0.01) while vlPAG and CeA rats failed to discriminate (p > 0.1 in both cases).

Table 1.

Mean (± SEM) % Time Freezing (Left Column) and mean (± SEM) lever-press rates (Right column) for CS+ and CS− at the end of first-order conditioning and for the CS+ and CS− following the SOCS+ and SOCS− in second-order conditioning are shown for Sham, vlPAG and CeA rats. For all groups, performance in first- and second-order conditioning was statistically identical.

| % Time Freezing | Lever-Press Rate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Order | Following Second-Order | First-Order | Following Second-Order | |||||

| CS+ | CS− | CS+ | CS− | CS+ | CS− | CS+ | CS− | |

| Sham | 55.6 ± 8.9 | 12.1 ± 3.8 | 53.5 ± 6.2 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 1.3 |

| vlPAG | 30.4 ± 11.3 | 9.8 ± 7.0 | 36.0 ± 6.3 | 13.1 ± 5.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 1.0 |

| CeA | 25.0 ± 8.3 | 8.3 ± 3.6 | 33.8 ± 6.8 | 8.8 ± 4.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 7.7 ± 1.8 |

Across second-order conditioning sham rats developed significant freezing to the SOCS+ but not the SOCS− while vlPAG and CeA rats failed to acquire second-order freezing (see Fig. 4 A–C). No effects of lesion, session or the lesion × session interaction were found (p > 0.1 in all cases) on pre-CS freezing. Repeated measures ANOVA for SOCS+ and SOCS− freezing over the five sessions of second-order conditioning found significant effects of session (F(4,80) = 2.84, p < 0.05) and cue (F(1,20) = 14.04, p < 0.05). More importantly, a significant interaction of lesion × cue (F(2,20) = 6.10, p < 0.05) was also found. Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s HSD found that Sham rats froze significantly more to SOCS+ than SOCS− (p < 0.05) while vlPAG and CeA rats did not (p > 0.1 in both cases).

Figure 4.

Freezing and instrumental suppression in second-order Pavlovian fear conditioning. (A–C) Mean (± SEM) % time freezing during SOCS+ (closed shapes) and SOCS− (open shapes) over the course of second-order Pavlovian fear conditioning. (D–F) Mean (± SEM) lever-press rates during SOCS+ and SOCS− from the same sessions. Data points 1–5 are the five sessions of second-order conditioning. Sham (circles), vlPAG (triangles) and CeA (diamonds) rats are shown in three separate columns.

Second-order conditioned suppression

Sham, vlPAG and CeA rats showed an identical pattern of lever-press suppression to the CS+ and CS− that followed the SOCS+ and SOCS− in second-order conditioning as they did to the CS+ and CS− at the end of first-order conditioning (see Table 1). Repeated measures ANOVA was performed comparing lever-press rates in the final block of first-order conditioning to CS+ and CS− lever-press rates that followed the SOCS+ and SOCS− over the five sessions of second-order conditioning. A significant effect of cue (F(3,60) = 54.11 p < 0.01) but not the cue × lesion interaction (F(6,60) = 0.79 p > 0.1) was observed. Post-hoc comparisons with Tukey’s HSD revealed that Sham, vlPAG and CeA rats lever-pressed at identical levels to the CS+ in first- and second-order conditioning (p > 0.1 in all cases). The same was true of CS− lever-pressing (p > 0.1 in all cases). Importantly, and like in first-order conditioning, Sham, vlPAG and CeA rats showed excellent discriminative lever-pressing between CS+ and CS− following the SOCS+ and SOCS− (p < 0.05 in all cases).

Across second-order conditioning Sham rats, but not vlPAG or CeA, showed greater lever-press suppression to the SOCS+ compared to the SOCS− (see Fig. 4D–F). As with freezing, repeated measures ANOVA for baseline lever-press rates (Sham: 9.8 ± 1.53; vlPAG: 10.1 ± 1.25; and CeA: 8.7 ± 2.09) revealed no significant differences between lesion groups (p > 0.1 in all cases) Repeated measures ANOVA for SOCS+ and SOCS− lever-press rates revealed a significant effect of session (F(4,80) = 5.31, p < 0.01). More importantly, and like for second-order freezing, a significant lesion × cue interaction (F(2,20) = 3.64, p < 0.05) was also found. Post-hoc comparisons found that Sham rats made fewer lever-presses during the SOCS+ relative to SOCS− (p < 0.05) while vlPAG and CeA rats lever-pressed at identical rates during SOCS+ and SOCS− (p > 0.1 in both cases). The percent change from baseline during SOCS+ for each group was; Sham: 87.7%, vlPAG: 112.0%, and CeA: 123.2%.

General Discussion

In Pavlovian fear conditioning, sham rats quickly acquired conditioned freezing and conditioned suppression to the CS+ and were showing robust discrimination in both freezing and suppression by the end of first-order conditioning. The absolute levels of conditioned freezing and conditioned suppression were much lower in second-order conditioning. Nevertheless, rats acquired freezing and suppression to the SOCS+ that was much greater than SOCS−. These findings are consistent with previous accounts which show that both first- and second-order Pavlovian fear conditioning produce robust freezing and suppression of lever-pressing.

Effects of CeA lesions

CeA lesions produced significant deficits in the acquisition and discrimination of first-order conditioned freezing, but left first-order conditioned suppression relatively intact. Because the lesions were made prior to training, we cannot specify the exact contribution of the CeA to conditioned freezing. Lesions may have impaired either the acquisition or performance of freezing. Other studies have found similar effects of the CeA lesions [12, 14] but see [21]. Like first-order conditioned freezing, CeA lesions significantly impaired the acquisition of second-order conditioned freezing. At no point did CeA rats show differential freezing to the SOCS+ that exceeded the SOCS−. These data clearly demonstrate that the CeA plays a critical role in the acquisition of both first- and second-order conditioned freezing. Future experiments will need to more specifically address the contribution of the CeA to second-order conditioned freezing when first-order conditioned freezing is not, or is at least minimally, disrupted.

Our conditioned suppression results are consistent with previous findings for the CeA which found that lesions impair conditioned suppression with minimal training but that with further training the deficit is overcome [14]. This suggests that the CeA normally contributes to, but is not essential for, the acquisition of conditioned suppression (but see [22]). In contrast, CeA rats failed to show any evidence of second-order conditioned suppression. This is despite showing excellent discriminative suppression to the first-order cues that followed the second-order cues. The CeA is critical to the acquisition of second-order conditioned suppression but less critical to the acquisition of first-order conditioned suppression.

Effects of vlPAG lesions

Selective vlPAG lesions produced smaller deficits in first-order conditioned freezing than previously reported [11, 16, 17]. The freezing observed in our vlPAG rats may then arise from intact portions of vlPAG spared by the electrolytic lesions. However, our vlPAG lesions appear to be more selective than previous lesions [11, 17, 18]. The greater deficits in those studies may have resulted from the combined damage of vlPAG and the lateral and dorsolateral PAG. In the previous study with the most selective lesions, vlPAG rats appeared to acquire post-shock freezing, albeit at levels significantly lower than Sham rats [16].

Another important difference between the present and previous studies is conditioning procedures employed. In previous studies rats received a total of three [11], three [16], or four [17] foot-shocks in the entire experiment. This is equivalent to stopping midway through or after session two of our experiment. Had we stopped there, our results would have matched previous results very well. Additionally, in the present experiment fear conditioning took place over many sessions with long inter-trial intervals, while previous studies used many fewer sessions and shorter inter-trial intervals. Another indication that our lesions were sufficient to produce deficits was the performance of vlPAG rats in second-order conditioned freezing. VlPAG rats failed to show conditioned freezing to the SOCS+. While different in some aspects, our results support previous findings of a role for the vlPAG in first-order conditioned freezing and extend its function to second-order conditioned freezing.

Despite their failure to show discrimination in first-order conditioned freezing, vlPAG rats showed excellent discrimination in first-order conditioned suppression. This is in accordance with Amorapanth et al. (1999), who reported larger first-order conditioned freezing deficits in rats with PAG lesions; yet, the same lesioned rats were fully capable of first-order conditioned suppression. Selective vlPAG lesions produced significant deficits in second-order conditioned suppression. If our vlPAG lesions were simply ineffective then no second-order deficit could have been observed. Our data provide further evidence the vlPAG is not necessary for the acquisition of first-order conditioned suppression and the first evidence that the vlPAG is necessary for the acquisition of second-order conditioned suppression.

Assessing fear with conditioned freezing and conditioned suppression

It is widely accepted that through pairings with aversive foot-shock a CS will come to elicit a central state of fear. This central state of fear can then be expressed through a variety of autonomic and behavioral systems. The results from second-order conditioning suggest that, at times, conditioned suppression may be more the product of conditioned freezing. VlPAG and CeA lesions that abolished second-order conditioned freezing also abolished second-order conditioned suppression. Pavlovian first-order fear conditioning produces robust freezing that undoubtedly contributes to conditioned suppression. However, given that impairments in first-order conditioned freezing produced by vlPAG or CeA lesions were not reflected in first-order conditioned suppression, behavioral mechanisms in addition to freezing must be contributing to first-order conditioned suppression.

One possibility is that conditioned suppression is mediated by punishment. On the first CS+ trial rats are busily pressing the lever for food and are then shocked. Thus, they may have learned that in presence of the CS+ a lever press will produce shock. While this mechanism could contribute to the acquisition of conditioned suppression it is not sufficient to explain why suppression is maintained. Well after rats cease to lever-press during the CS+, they continue to receive foot-shocks following CS+ termination. If learning only consisted of punishment then CS+ suppression should lessen over time because the contingency between lever-pressing and foot-shock has been abolished. This pattern was not observed.

More plausible are two different behavioral mechanisms. First, conditioned suppression may occur by way of conditioned place avoidance. Rats learn that foot-shock is associated with area of the chamber near the lever, avoiding that area when the CS+ is presented. Consistent with this idea, intra-amygdala muscimol infusion (which included the CeA as well as other amygdalar regions) impairs the expression of place avoidance [24]. Thus, the slowed acquisition of first-order conditioned suppression in CeA may have been due to a failure to avoid the area near the lever, rather than a deficit in freezing. A second behavioral mechanism was proposed by Estes and Skinner (1941). In their original demonstration of conditioned suppression [6] they described the CS+ as functioning to produce a central state of ‘anxiety,’ although today we might use the term ‘fear’. This central state of fear inhibits the motivational state of hunger. Conditioned suppression is then the product of competition between central states of anxiety and hunger. Rats that are not hungry are unwilling to work for food. Supporting such an account, a recent study the effects of CeA and BLA lesions on the suppression of feeding by Pavlovian fear cues. Fear cues produce both significant freezing and suppression of feeding in normal rats. CeA and BLA lesions disrupted freezing however; BLA, but not CeA rats suppressed feeding [25]. Thus, the CeA may play a critical role in the ability of a Pavlovian fear cue to inhibit the motivational state of hunger. Although the present experiment cannot specify which behavioral mechanism contributes to first-order conditioned suppression in the absence of freezing it is clear that conditioned suppression is normally the product of several behavioral mechanisms.

The neural circuitries responsible for Pavlovian fear

The CeA and vlPAG normally contribute to the acquisition and/or expression of fear through freezing. However, when fear is assessed with first-order conditioned suppression no role for the vlPAG is found while the role of the CeA is diminished. What neural circuitries are responsible for mediating conditioned suppression independent of freezing? It is likely that the CeA is a component, as lesions transiently impair the acquisition of first-order conditioned suppression [14]. A similar effect has been reported for lesions of the BLA [14], making it another candidate structure. Notably, the vlPAG does not appear to be part of this circuit [17]. Parallel circuitries through the BLA and CeA may be responsible for conditioned suppression that is independent of freezing. Interestingly, it was found that when both the BLA and CeA were lesioned rats failed to show any evidence of first-order conditioned suppression [14]. Future work will better define the behavioral mechanism contributing to first-order conditioned suppression and examine the timeline of CeA and vlPAG involvement in first- and second-order conditioned suppression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIMH grant MH5366 to Dr. Peter C. Holland and National Service Research Award MH075302 to MAM and is a part of a doctoral dissertation completed by MAM in the laboratory of PCH. I thank PCH for his guidance and comments on the manuscript as well as Dr. Charles Pickens and Dr. Michael Saddoris for helpful comments and discussion. I also thank Weidong Hu for excellent technical assistance with histology. Experiments were conducted in full compliance to protocols established by the Johns Hopkins University IACUC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Davis M. Pharmacological and anatomical analysis of fear conditioning using the fear-potentiated startle paradigm. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1986;100:814–824. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.100.6.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapp BS, Frysinger RC, Gallagher M, Haselton JR. Amygdala central nucleus lesions: effect on heart rate conditioning in the rabbit. Physiology & Behavior. 1979;23:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwata J, LeDoux JE, Reis DJ. Destruction of intrinsic neurons in the lateral hypothalamus disrupts the classical conditioning of autonomic but not behavioral emotional responses in the rat. Brain Research. 1986;368:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolles RC, Collier AC. The effect of predictive cues on freezing in rats. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1976;4:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SD, Rivers S, Bevins RA, Ayres JJ. Conditioned stimulus determinants of conditioned response form in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1996;22:87–104. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.22.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes KW, Skinner BF. Some Quantitative Properties of Anxiety. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1941;29:390–400. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouton ME, Bolles RC. Conditioned fear assessed by freezing and by the suppression of three different baselines. Animal Learning & Behavior. 1980;8:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mast M, Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC. The relationship between freezing and response suppression in a CER situation. Psychological Record. 1982;32:151–167. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizley RC, Rescorla RA. Associations in second-order conditioning and sensory preconditioning. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1972;81:1–11. doi: 10.1037/h0033333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilensky AE, Schafe GE, Kristensen MP, LeDoux JE. Rethinking the fear circuit: The central nucleus of the amygdala is required for the acquisition, consolidation, and expression of pavlovian fear conditioning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:12387–12396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4316-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Oca BM, DeCola JP, Maren S, Fanselow MS. Distinct regions of the periaqueductal gray are involved in the acquisition and expression of defensive responses. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:3426–3432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03426.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goosens KA, Maren S. Contextual and auditory fear conditioning are mediated by the lateral, basal, and central amygdaloid nuclei in rats. Learning & Memory. 2001;8:148–155. doi: 10.1101/lm.37601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nader K, Majidishad P, Amorapanth P, LeDoux JE. Damage to the lateral and central, but not other, amygdaloid nuclei prevents the acquisition of auditory fear conditioning. Learning & Memory. 2001;8:156–163. doi: 10.1101/lm.38101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JL, Dickinson A, Everitt BJ. Conditioned suppression and freezing as measures of aversive Pavlovian conditioning: effects of discrete amygdala lesions and overtraining. Behavioral Brain Research. 2005;159:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amorapanth P, LeDoux JE, Nader K. Different lateral amygdala outputs mediate reactions and actions elicited by a fear-arousing stimulus. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:74–79. doi: 10.1038/71145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JJ, Rison RA, Fanselow MS. Effects of Amygdala, Hippocampus, and Periaqueductal Gray Lesions on Short-Term and Long-Term Contextual Fear. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1993;107:1093–1098. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.107.6.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amorapanth P, Nader K, LeDoux JE. Lesions of periaqueductal gray dissociate-conditioned freezing from conditioned suppression behavior in rats. Learning & Memory. 1999;6:491–499. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.5.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ. Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:2517–2529. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02517.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDannald M, Kerfoot E, Gallagher M, Holland PC. Amygdala central nucleus function is necessary for learning but not expression of conditioned visual orienting. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;20:240–248. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanson LW. Brain Maps: Structure of the Rat Brain. 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koo JW, Han JS, Kim JJ. Selective neurotoxic lesions of basolateral and central nuclei of the amygdala produce differential effects on fear conditioning. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:7654–7662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1644-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Killcross S, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Different types of fear-conditioned behaviour mediated by separate nuclei within amygdala. Nature. 1997;388:377–380. doi: 10.1038/41097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellicutt MH, Schwartzbaum JS. Formation of a conditioned emotional response (CER) following lesions of the amygdaloid complex in rats. Psychological Reports. 1963;12:351–358. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holahan MR, White NM. Intra-amygdala muscimol injections impair freezing and place avoidance in aversive contextual conditioning. Learning & Memory. 2004;11:436–446. doi: 10.1101/lm.64704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrovich GD, Ross CA, Mody P, Holland PC, Gallagher M. Central, but not basolateral, amygdala is critical for control of feeding by aversive learned cues. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:15205–15212. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3656-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]