Abstract

Although the general trauma literature links disclosure of abuse to positive psychological and physical health outcomes, findings for sexual assault survivors are mixed. Supportive responses can reaffirm self-worth; however, negative responses can increase feelings of shame and isolation. This study examined the effects of disclosure in a community sample of Caucasian and African American sexual assault survivors who completed computer-assisted self-interviews. Among the 58.6% of survivors who had disclosed to someone (n = 136), 96% had disclosed to at least 1 informal and 24% at least 1 formal support provider. The experiences of African American and Caucasian survivors were similar in many ways. Participants received more positive than negative responses from others, although only negative responses were related to posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and particularly so for African American participants. Regretting disclosure and disclosure to formal providers were also related to posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Suggestions are made for programs to decrease negative responses to disclosure.

Keywords: sexual assault, disclosure, posttraumatic stress disorder, social reactions, ethnicity

Almost 25 years ago, Mary Koss (1985) described rape as a hidden epidemic because it was so rarely recognized and reported. This statement is still valid. Sexual assault and other forms of sexual violence against women carry a stigma that deters disclosure to both formal and informal sources (Filipas & Ullman, 2001; Fisher, Daigle, Cullen, & Turner, 2003; Ullman, Starzynski, Long, Mason, & Long, 2008; Wyatt, 1992). So many sexual assault survivors have provided anguished accounts of the blame and recrimination received from others that these negative responses to disclosure have been labeled “the second rape” (Ahrens, Campbell, Ternier-Thames, Wasco, & Sefl, 2007; Campbell et al., 1999; Starzynski, Ullman, Filipas, & Townsend, 2005).

Sexual assault is a major trauma that disrupts survivors’ lives in a myriad of ways. Survivors are at heightened risk for a variety of physical health problems, anxiety, depression, difficulty trusting others, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use (Campbell, Greeson, Bybee, & Raja, 2008; Golding, 1999; Ullman, Townsend, Filipas, & Starzynski, 2007). When sexual assault survivors reach out to others for support and instead receive a negative response, they are likely to experience additional psychological trauma. Therefore, it is important to explore the role of disclosure in the recovery process. This article examines the effects of disclosure on PTSD symptomatology among a community sample of African American and Caucasian survivors of adolescent and adult sexual assault. The relevant literature is briefly reviewed, and then the study’s goals and hypotheses are described.

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DISCLOSURE, RESPONSES FROM OTHERS, AND WELL-BEING

Disclosure has been linked to improved psychological and physical well-being for survivors of many different types of trauma, including sexual assault (Broman-Fulks et al., 2007; Pennebaker, 2000; Ullman & Filipas, 2001). The benefits of disclosure occur through several mechanisms, including social support (Ahrens et al., 2007; Frazier, Tashiro, Berman, Steger, & Long, 2004; Ullman, 1999). A vast literature documents the advantageous effects of social support on psychological and physical health outcomes (see Uchino, 2004, for a review). In studies of sexual assault survivors, receiving social support has been associated with a variety of positive outcomes, including positive life change and growth as well as reduced PTSD and depressive symptoms (Borja, Callahan, & Long, 2006; Filipas & Ullman, 2001; Schumm, Briggs-Phillips, & Hobfoll, 2006). For example, Filipas and Ullman found that the greater the amount of support survivors reported receiving, the greater their positive affect, the lower their negative affect, and the fewer PTSD symptoms they had.

Unfortunately, disclosure does not always produce a supportive response (Starzynski et al., 2005; Ullman, 1999; Ullman, Filipas, Townsend, & Starzynski, 2007). Many survivors receive judgmental comments from friends and family that heighten their negative affect and sense of isolation (Golding, Wilsnack, & Cooper, 2002). For example, in a large community sample of mostly minority survivors, Ullman, Filipas, et al. (2007) found that negative reactions from others predicted PTSD symptom severity.

CHARACTERISTICS OF DISCLOSURE RECIPIENTS

Surprisingly little research has focused on the recipients of disclosure and how their characteristics might influence the disclosure process and outcomes for survivors. Several researchers have focused on the effects of disclosing to formal versus informal support sources (Borja et al., 2006; Starzynski et al., 2005). Disclosure to informal sources, such as family members and friends, is more common than disclosure to formal sources, such as police officers, medical personnel, and mental health professionals (Ahrens et al., 2007; Fisher et al., 2003; Ullman, 2007). For example, 38% of the survivors in Ahrens and colleagues’ study of rape victims first disclosed to a friend, whereas 6% first disclosed to the police. Starzynski et al. (2005) found that survivors who disclosed their experience to both formal and informal support sources reported more severe PTSD symptoms and more frequent negative social reactions than did those who disclosed to informal sources only.

OVERVIEW OF STUDY GOALS AND HYPOTHESES

This study has three primary goals. The first is to describe the characteristics of the disclosure experience. What are the reasons for disclosure? To whom do sexual assault survivors typically disclose their experiences? To what extent do survivors receive positive and negative responses to disclosure? Do survivors sometimes regret their decision to disclose, and if so, why? Because so little research has addressed these basic questions, this goal was viewed primarily as exploratory. We expected that participants would be more likely to disclose to informal sources than formal sources, would be more likely to disclose to women than men, and that overall they would receive more positive than negative responses (Ahrens et al., 2007; Ullman, 1999).

The second goal is to examine the relationships between disclosure characteristics and PTSD symptom frequency. We hypothesized that disclosure to formal providers would be positively related to PTSD symptoms for two reasons. First, sexual assaults that involve more serious injuries are more likely to be reported to the authorities and to produce PTSD symptoms (Ullman, 1999). Second, the negative responses commonly received from formal providers were hypothesized to exacerbate PTSD symptoms. We also hypothesized that there would be a positive relationship between the number of reasons that survivors had for seeking support and PTSD symptoms. Survivors with many reasons for disclosure are likely to have many unresolved issues that increase their PTSD symptoms. Based on the general social relationships literature, we hypothesized that socially supportive responses would decrease PTSD symptoms, whereas negative responses from others would increase PTSD symptoms (Helgeson, Novak, Lepore, & Eton, 2004; Herbert & Dunkel-Schetter, 1992; Ullman, 1999). Finally, we hypothesized that regret would be related to more frequent PTSD symptoms. Survivors who wished that they had not disclosed what had happened to someone had presumably received responses that made them feel worse, thus heightening their PTSD symptoms.

The final goal is to compare and contrast the disclosure experiences of African American and Caucasian survivors. Research with diverse populations of sexual assault survivors is limited, and few studies have focused on the experiences of African American sexual assault survivors (see Abbey, Jacques-Tiura, & Parkhill, in press, for a review). Based on the findings from other community-based samples, we hypothesized lower rates of disclosure among African American survivors as compared to Caucasian survivors (Ullman et al., 2008; Wyatt, 1992). Rape myths and victim blame have a negative impact on all survivors and have encouraged their silence; however, African American women may be especially unlikely to disclose. African Americans’ history of slavery and racial discrimination has had a profound impact on survivors’ willingness to disclose what has happened, particularly to authorities (Donovan & Williams, 2002; West, 2006; Wyatt, 1992). Throughout the period of slavery, African American women were frequently raped by White men who viewed them as sexual commodities. For many years after slavery ended, rape laws still did not apply to African American women, codifying rape myths about their sexual availability. In addition, the high incarceration rate of African Americans has produced widespread distrust of the criminal justice system, thus increasing victims’ reluctance to file a formal report (Neville & Pugh, 1997; Wyatt, 1992). Thus, African American women are expected to be less likely than Caucasian women to disclose sexual assaults to formal sources because they feel that their claims will not be taken seriously and may perpetuate stereotypes of sexual violence within the African American community, they feel disloyal for reporting an assault by an African American man, and they anticipate being derogated (Holzman, 1996; Washington, 2001; West, 2006). We expected that these fears were accurate and hypothesized that African American women who reported to formal authorities would experience more negative responses than would Caucasian women.

Hypotheses about disclosure to informal sources were more difficult to make. The literature suggests that many African American women endorse the strong Black matriarch stereotype, which emphasizes personal strength and resilience, and which may lead them to turn inward rather than to others for support in times of trouble (Donovan & Williams, 2002; Pierce-Baker, 1998; Washington, 2001). Although the family is a great source of strength for African American women, some research suggests that women sometimes intentionally avoid discussing traumatic events that may upset the family system (Boyd-Franklin, 1989; Neville & Pugh, 1997). Findings are mixed (Neville & Pugh, 1997); however, several studies have found that victim blaming and race–gender stereotyping are still pervasive within the African American community (Neville, Heppner, Oh, Spanierman, & Clark, 2004; Robinson, 2002). This literature suggests that African American women may be less likely than Caucasian women to disclose to informal sources and may be more likely to receive more negative, judgmental comments when they disclose.

METHOD

Participants

A representative community sample of 272 African American and Caucasian women from a large metropolitan area was recruited for a study of dating experiences (see Abbey, BeShears, Clinton-Sherrod, & McAuslan, 2004, for more information on the data collection procedures). Potential participants were required to be between the ages of 18 and 49, to be single, to have dated a man in the previous 2 years, and to have lived in the United States for at least 10 years. Given this study’s focus on the effects of disclosing adolescent and adult sexual victimization, the sample was restricted to women who reported having experienced an unwanted sexual experience since age 14 (n = 232) and who had disclosed the experience to at least one person (n = 136). The median annual household income for this subsample was in the range of $30,000 to $34,999. Caucasian survivors (M range = $45,000–$49,999) reported a significantly higher household income than African American survivors (M range = $25,000–$29,999), t(134) = 4.82, p < .01. Of the participants, 93% had completed high school. The mean level of education attained by African American and Caucasian survivors corresponded to “some college” (p > .05).

Procedure

Potential participants were identified by Wayne State University’s Center for Urban Studies using random-digit dialing. They were asked to participate in an in-person study of women’s good and bad dating experiences. Interviews were completed with 81.7% of eligible women. Participants were interviewed by trained female interviewers of the same ethnicity. The consent form described the content of the interview, including questions about unwanted sexual activity. The consent form also included contact information for several free and low-cost local rape crisis and counseling agencies. After obtaining participants’ consent, interviewers demonstrated how to use the laptop computer so that participants could complete the questions on their own. Interviewers sat across from participants to ensure participants’ privacy and were available to answer questions throughout the interview. Interviewers were trained to handle expressions of negative affect and to obtain assistance if participants experienced extreme distress (however, this did not occur). At the conclusion of the interview, participants reported their current affect. Reports of feeling angry, sad, embarrassed, and anxious were all low (all Ms < 1.79 on a scale of not at all [1] to very [5]), and there were no ethnic group differences. Participants were given $50 to compensate for their time. All aspects of the study were approved by the university’s Human Investigation Committee.

Measures

Demographics

Participants’ ethnicity was assessed with a single self-report item during the telephone screening. All other measures were included in the computerized self-interview. Household income was assessed with a single item, with options ranging from 0 to $9,999 (1) to $100,000 or more (20). Education was assessed with a single item, with options ranging from some grade school (1) to doctoral degree (11).

Social desirability

Ballard’s (1992) 13-item measure was used to assess social desirability. Response options are true or false, and the mean was computed such that higher scores reflected more socially desirable responses.

Sexual assault severity

A modified 17-item version of the Sexual Experiences Survey was used to assess experiences with unwanted sex since the age of 14 (Koss et al., 2007). Although severity can be defined by multiple criteria, for this study it was based on the type of forced sexual experience with forced sexual contact, verbally coerced sexual intercourse, attempted rape, and completed rape representing lowest to highest severity.

Reasons for seeking support

In the context of describing one forced sexual experience in detail, participants were asked if they had told anyone about what had happened. If they had disclosed the experience to anyone, they answered a series of follow-up questions. Participants’ reasons for disclosure were assessed with a checklist of 21 possible reasons for telling someone about the sexual assault. Participants could select as many reasons as they wanted, including an “other” option. The list of reasons appears in Table 1 and was based on past research and our pilot studies. Because 13 of these reasons correlated highly, we combined them into an index labeled “number of reasons for seeking support” by summing affirmative responses. Cronbach’s alpha was .78.

TABLE 1.

Reasons for Disclosure

| For What Reasons Did You Decide to Tell Those People? | Percent Endorsed |

χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 136) | African Americans (n = 66) | Caucasians (n = 70) | ||

| You were close to the person you told.a | 60 | 52 | 67 | 3.44 |

| You needed to talk to someone.a | 58 | 58 | 59 | 0.01 |

| You talk about everything with the person.a | 39 | 27 | 50 | 7.38** |

| You wanted someone else to be aware of the situation. | 35 | 33 | 37 | 0.21 |

| You needed support or comfort.a | 33 | 26 | 40 | 3.11 |

| You needed advice.a | 32 | 26 | 39 | 2.55 |

| You were afraid.a | 24 | 26 | 21 | 0.35 |

| You felt the person you told could keep a secret.a | 23 | 18 | 27 | 1.55 |

| You could no longer deal with it on your own.a | 22 | 21 | 23 | 0.05 |

| You felt the person was a good listener.a | 22 | 15 | 29 | 3.56 |

| You felt the person gave good advice.a | 21 | 18 | 24 | 0.75 |

| You needed help figuring out what happened.a | 18 | 14 | 23 | 1.92 |

| You felt guilty.a | 18 | 12 | 23 | 3.69 |

| Because the person had a similar situation.a | 13 | 14 | 13 | 0.02 |

| You were asked or questioned about the incident. | 12 | 15 | 9 | 1.41 |

| You felt it would help others understand you better. | 8 | 8 | 9 | 0.05 |

| To help another person going through similar situation. | 6 | 11 | 1 | 5.17* |

| The man needed to be prosecuted. | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.28 |

| The other person witnessed the incident. | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.28 |

| You do not know or cannot remember. | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Other. | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0.91 |

Items included in a summed “number of reasons for seeking support” composite.

p < .05

p < .01

Relationship to disclosure recipients

Participants were asked about their relationship to everyone they had told about the assault. The list of recipients appears in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Relationship to Disclosure Recipients

| Who Did You Tell? | Percent Endorsed |

χ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 136) | African Americans (n = 66) | Caucasians (n = 70) | ||

| Female friend | 68 | 53 | 81 | 12.52** |

| Mother | 24 | 35 | 14 | 7.82** |

| Male friend | 24 | 18 | 30 | 2.58 |

| Sister | 22 | 30 | 14 | 5.07* |

| Other female family member | 22 | 32 | 13 | 7.10** |

| Counselor or therapist | 11 | 18 | 19 | 0.01 |

| Brother | 10 | 15 | 6 | 3.28 |

| Husband or boyfriend | 10 | 11 | 9 | 0.16 |

| Father | 8 | 11 | 6 | 1.09 |

| Other male family member | 8 | 11 | 6 | 1.09 |

| Religious leader | 8 | 14 | 3 | 5.31* |

| Police | 7 | 11 | 4 | 1.99 |

| Other | 5 | 8 | 3 | 1.55 |

p < .05

p < .01

Social support and disregard

Supportive and nonsupportive responses from others were assessed using Abbey, Andrews, and Halman’s (1995) measure of social support and disregard. Response options ranged from not at all (1) to very much (5). The 6-item emotional support scale assessed the esteem and affirmation components of social support. A sample item is “To what extent did these people show that they loved and cared for you?” Cronbach’s alpha was .92. The 7-item disregard scale assessed expressions of negative affect and disapproval. A sample item is “To what extent did these people make you feel like you acted inappropriately or did something wrong?” Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

Regret and the wish that one had not disclosed

Participants were asked if there was anyone they wished they had not told about the assault, with options of no (0) or yes (1). Those who answered yes were asked two follow-up questions. They were first asked which individuals they wished they had not told, using the list of possible relationships previously described. They were then asked why they wished they had not told these people. Participants were provided with eight reasons and endorsed all that applied, including an “other” response. Sample items are “The person made you feel ashamed or embarrassed” and “The person made you feel that it was your fault or you had done something wrong.”

Frequency of PTSD symptoms

Davidson’s 17-item Trauma Scale was used to assess the frequency of PTSD symptoms (Davidson et al., 1997). This scale was designed to reflect all PTSD symptoms listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and has good reliability and validity. A sample item is “How frequently have you had painful images, memories or thoughts of the event?” Response options ranged from not at all (1) to all of the time (5). Cronbach’s alpha in this study was .95.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Disclosure Experience

As noted earlier, these analyses were restricted to the subsample of participants (n = 136) from the larger study who had disclosed a sexual assault to at least one person. Caucasian survivors (67%) were significantly more likely than African American survivors (52%) to have disclosed, χ2 = 4.95, df = 1, N = 232, p < .05. When asked why they had disclosed, participants endorsed each of the possible 21 reasons, although some reasons were much more frequently endorsed than others. As can be seen in Table 1, more than half of participants had told someone about the assault because they were close to the person and they needed to talk to someone about what had happened. Other reasons endorsed by more than 30% of participants were that they talked to that person about everything, wanted someone else to be aware of the situation, needed support, and needed advice. Only a few participants mentioned prosecution of the offender as a reason for disclosure. The rank ordering of the reasons provided by African American and Caucasian participants was very similar. More Caucasian than African American participants had disclosed because they talked about everything with that person. In contrast, more African American than Caucasian participants had disclosed to help another person going through a similar situation (although there were no differences in endorsement of the related item “because the person had a similar situation”). When we counted participants’ reasons for seeking support, we found that Caucasians (M = 4.37, SD = 2.88) sought support for significantly more reasons than did African Americans (M = 3.26, SD = 2.98), t(134) = 2.22, p < .05.

Overall, 96% of participants had disclosed to at least one informal support provider, and 24% had disclosed to at least one formal support provider. Caucasian survivors (99%) were marginally more likely to have disclosed to an informal support provider than were African American survivors (92%), χ2 = 3.04, df = 1, N = 136, p = .08. There were no ethnic group differences in the proportion of survivors who had disclosed to a formal provider. As can be seen in Table 2, more than half of participants reported that they had told a female friend about what had happened. Although female friends were the most commonly mentioned confidant for both African American and Caucasian survivors, Caucasian women were especially likely to have disclosed to a female friend. For African American women, their mother was the second most likely person to whom they had disclosed the assault, whereas for Caucasian women the second most likely person was a male friend. African American women were more likely than Caucasian women to have disclosed to their sister, other female family members, and a religious leader. Similar proportions of African American and Caucasian survivors had disclosed their experience to male friends, a counselor or therapist, husband or boyfriend, father, brother, other male family members, and the police.

Three summative measures were examined. The total number of types of disclosure recipients was summed. African American survivors (M = 2.65, SD = 2.00) had disclosed to marginally more types of sources than had Caucasian survivors (M = 2.07, SD = 1.67), t(134) = 1.84, p = .07. Then the total number of types of female and male informal confidants was separately summed. Within-subject analyses indicated that participants were more likely to have disclosed to a female friend or family member (M = 1.36, SD = 0.92) than to a male friend, family member, or partner (M = 0.60, SD = 0.88), t(135) = 9.33, p < .01. This finding was comparable for African American and Caucasian participants.

Participants received significantly more support than disregard from others, t(135) = 18.94, p < .001 (see the bottom two rows of Table 3 for the means and standard deviations). Levels of social support were high and did not differ for African American and Caucasian participants. Levels of disregard were fairly low; however, African American participants (M = 1.77, SD = 0.90) received more negative responses than did Caucasian participants (M = 1.47, SD = 0.65), t(134) = 2.21, p < .05. There were no differences in the levels of social support or disregard received when we compared those who had disclosed to a formal support provider with those who had not. However, among participants who had disclosed to a formal provider, African American survivors (M = 1.90, SD = 0.91) received significantly more disregard than did Caucasian survivors (M = 1.29, SD = 0.69), t(31) = 2.13, p < .05. There were no group differences in positive responses among those who had disclosed to a formal source.

TABLE 3.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics (N = 136)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Disclosure to formal support providera | — | |||||

| 2. Number of reasons for seeking support | .07 | — | ||||

| 3. Social support | .11 | .05 | — | |||

| 4. Disregard | .02 | −.07 | −.59** | — | ||

| 5. Regret disclosurea | −.05 | .02 | −.33** | .41** | — | |

| 6. PTSD symptom frequency | .44** | .22** | −.12 | .23** | .26** | — |

| Mean or proportion endorsed | 0.24 | 3.83 | 4.15 | 1.62 | 0.18 | 2.07 |

| SD | 2.97 | 0.96 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

No = 0, yes = 1. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

p < .01

Of participants, 18% (n = 25) wished they had not told someone about the sexual assault. Female friends (n = 8) and mothers (n = 6) were the confidants that participants most often regretted having told. The most common reasons for regretting disclosure were that the person made them feel ashamed or embarrassed (n = 12) and that the assault was their fault or they deserved it (n = 9). There were no differences in the regrets about disclosure reported by Caucasian and African American participants.

Relationships Between Disclosure and PTSD Symptoms

The relationships between disclosure characteristics and frequency of PTSD symptoms were examined in correlation and regression analyses. Table 3 presents the bivariate correlations. PTSD symptoms were positively related to disclosure to formal providers, the number of reasons for seeking support, the amount of disregard received from others, and regret about having told someone. Social support was unrelated to PTSD symptoms. Social support and disregard were inversely related. Participants who wished they had not told someone about the assault received less support and more disregard.

Separate correlation matrices were examined for African American and Caucasian participants. There was only one significant difference. The relationship between disregard and PTSD symptom frequency was significantly stronger for African Americans (r = .35) than for Caucasians (r = −.05, 95% confidence interval for the difference = 0.07–0.72).

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the combined effects of disclosure characteristics on PTSD symptom frequency. Demographic and control variables were included on the first step. Income and education were included because they are often highly correlated with ethnicity (see the Method section for a description of significant income differences found in this sample). Social desirability was included to control for differences in willingness to provide socially undesirable responses. Assault severity was included to control for its positive relationship to PTSD symptoms when evaluating the effects of disclosure. There were no ethnic group differences in social desirability or sexual assault severity. Aspects of the disclosure experience were included on the second step. Because of the significant difference in the correlation between disregard and PTSD symptoms for African American and Caucasian participants, the interaction between ethnicity and disregard (centered variable) was included on the third step.

As can be seen in Table 4, there were three significant predictors on the first step. More frequent PTSD symptoms were reported by African American survivors, by participants with lower social desirability scores, and by participants who had experienced more severe sexual assaults. These variables explained 13% of the variance in PTSD symptom frequency.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Predicting Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Frequency (N = 136)

| Variable | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||

| Ethnicitya | −0.35 | 0.16 | −0.19* |

| Income | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.07 |

| Education level | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.06 |

| Social desirability | −0.87 | 0.37 | −0.20* |

| Assault severity | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.21** |

| ΔR2 | 0.13** | ||

| Step 2 | |||

| Disclosure to formal support providerb | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.41** |

| Number of reasons for seeking support | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.21** |

| Social support | −0.05 | 0.09 | −0.05 |

| Disregard | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| Wish had not disclosed to someoneb | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.19* |

| ΔR2 | 0.25** | ||

| Step 3 | |||

| Ethnicity × Disregard | −0.42 | 0.18 | −0.22* |

| ΔR2 | 0.03* | ||

African American = 0, Caucasian = 1.

No = 0, yes = 1.

p < .05

p < .01

In the second step, PTSD symptom frequency was positively related to disclosure to a formal provider, more reasons for seeking support, and regret about having told someone. These variables explained an additional 25% of the variance in PTSD symptom frequency.

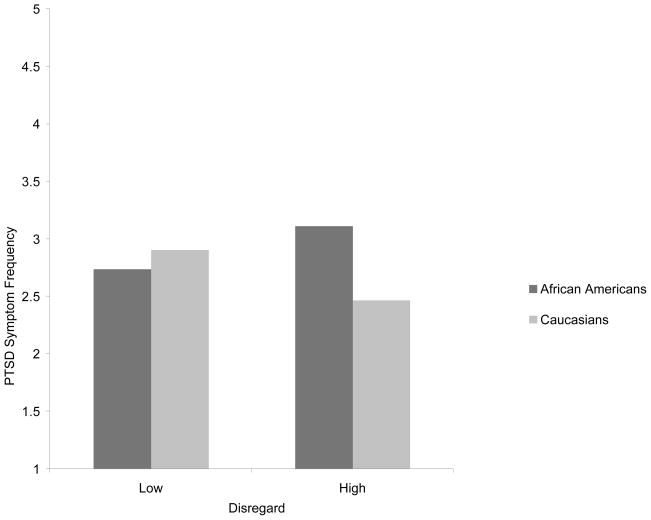

In the final step, the interaction between disregard and ethnicity was significant. It explained an additional 3% of the variance in PTSD symptom frequency, resulting in a total of 41% of the variance explained. As can be seen in Figure 1, among participants who received low levels of disregard from others, African Americans and Caucasians had comparable levels of PTSD symptom frequency, t(124) = 0.10, ns. In contrast, among participants who received high levels of disregard, African Americans had more frequent PTSD symptoms than did Caucasians, t(124) = 2.83, p < .01.

FIGURE 1.

The interactive effects of ethnicity and disregard on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom frequency.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the characteristics of African American and Caucasian sexual assault survivors’ disclosure experiences and identified aspects of the disclosure process that are associated with PTSD symptoms. Although some differences emerged, African American and Caucasian survivors had generally similar patterns of disclosure. As predicted, Caucasian survivors were more likely than African American survivors to have disclosed to someone and were marginally more likely to have disclosed to an informal source. Contrary to expectations, there were no differences in the likelihood of disclosure to a formal source. Participants had disclosed to more women than men. Participants had many reasons for disclosure, including having a close relationship with the confidant, needing to talk, wanting someone to be aware of what had happened, and needing comfort or advice. Overall, participants reported receiving high levels of social support and low levels of disregard from others. As found in the general and sexual assault support literature, negative responses from others had a stronger impact on well-being than did positive responses (Borja et al., 2006; Helgeson et al., 2004; Ullman, 1999; Ullman & Filipas, 2001). Almost 1 in 5 participants wished they had not told someone because of the negative responses they received, which made them feel ashamed and at fault. In multivariate analyses that controlled for income, education, social desirability, and assault severity, increased frequency of PTSD symptoms was related to being African American, disclosure to a formal provider, having many reasons for seeking support, regretting disclosing, and (for African Americans only) receiving high levels of disregard.

Some of these findings were expected based on past research; some were unexpected. Overall, these findings highlight the importance of discussing trauma with others and receiving responses that increase self-regard. Counselors, therapists, and religious leaders were the most frequently mentioned formal support providers, yet disclosure to a formal service provider was associated with increased PTSD symptoms. Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, there are multiple explanations for this finding. Some service providers may be judgmental and make sexual assault survivors feel ashamed and responsible for what happened. Also, survivors who are experiencing the worst PTSD symptoms are most likely to seek out formal support providers.

In this study, African American women reported more frequent PTSD symptoms than did Caucasian women. This finding was unexpected. As noted in the Method section, these participants came from a larger study that also included survivors who had not disclosed the sexual assault to anyone. There were no ethnic differences in rates of PTSD symptoms in the larger sample that included nondisclosers (Wegner, Abbey, Jacques-Tiura, & Tkatch, under review). In this study’s sample of disclosers, African American participants received more negative responses from others, and more negative responses if they had disclosed to formal service providers, than did Caucasian participants; and high levels of negative responses were associated with PTSD symptoms only for African American survivors. These negative responses from others may have reinforced distrust in the medical and judicial systems and may have reinforced the belief that formal service providers still hold racist stereotypes, exacerbating African American survivors’ negative affect, feelings of betrayal, and rumination. It is also possible that variables not included in this study, including other types of violence victimization and life stressors, underlie the higher rates of PTSD found for African Americans in these analyses. Most past research has not found differences in rates of PTSD among African American and Caucasian survivors (Epstein, Saunders, & Kilpatrick, 1997; Masho & Ahmed, 2007; Ullman & Filipas, 2001); thus, future research is needed that focuses on the mechanisms through which negative responses from others contribute to PTSD symptoms, particularly among African American survivors.

Overall, African American and Caucasian survivors had disclosed to similar types of people and for similar reasons, although a few differences were found. African American survivors were somewhat more likely than Caucasian survivors to have disclosed to mothers, sisters, other female family members, and religious leaders. Caucasian survivors were somewhat more likely than African American survivors to have disclosed to female friends. These differences reflect differences in the support networks of African American and Caucasian survivors and the people with whom these women feel most comfortable discussing traumatic experiences (Weist et al., 2007). Past research also suggests that African Americans are more likely than Caucasians to turn to religion following a sexual assault experience (Kennedy, Davis, & Taylor, 1998; Weist et al., 2007). Caucasians were more likely than African Americans to report that they had told someone about what had happened because they discuss everything with that person. African Americans were more likely than Caucasians to report that they had told someone about what had happened to help another person going through a similar situation. Taylor (2002) reported that giving testimony fostered feelings of empowerment and social responsibility among African American survivors.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths and limitations. The study’s strengths include the representative community sample of single women, the large proportion of African American participants, and the variety of measures of disclosure and others’ responses. One important limitation is the cross-sectional design. This design cannot determine whether disclosure characteristics produced increased PTSD symptoms or whether high levels of PTSD symptoms prompted disclosure, or whether another variable, such as neuroticism, caused both. Although the sample was representative, it was constrained to women who were currently single and who lived in one large metropolitan area. The interview was self-administered on a computer to enhance participants’ willingness to disclose sensitive information. This format, however, precluded the use of open-ended questions. Given how little is known about the disclosure process, semistructured interviews by well-trained interviewers would provide important information about aspects of the disclosure process that might not have been identified in this study. We did not ask participants how long after the assault disclosure had occurred. There are likely to be important differences between survivors who disclose to at least one person soon after the assault and those who wait many years to disclose (Ullman, 1999). Also, this study focused on the disclosure of one sexual assault that had occurred since the age of 14. Many women experience sexual trauma at earlier ages; thus, it is important to measure childhood and early adolescent victimization in future disclosure research. Other types of sexual violence, such as sexual harassment, stalking, and intimate partner violence, are also seldom disclosed, and consideration of the cumulative effects of different forms of sexual violence across the lifespan is likely to provide insight into factors that affect survivors’ psychological and physical health.

Suggestions for Future Research

Prospective studies would provide a better understanding of the temporal relationships between family history, preexisting mental and physical health, other traumatic life events, and characteristics of the sexual assault. Future studies should also include women who did not disclose to determine the factors that precluded them from disclosing and the impact that this has had on their mental and physical health.

Research is also needed that examines the disclosure and support process in more detail. If the amount of support and disregard received from each individual is separately assessed, then researchers can evaluate whether certain types of people (e.g., boyfriends, police) are most likely to provide negative responses that impede recovery. Information about the order in which disclosure occurs would also be useful. For example, what is the impact of telling several people immediately as compared to telling one person at a time? When the first confidant provides a negative response, are survivors less likely to tell anyone else, or do they continue to disclose until someone is supportive? In a small qualitative study, Ahrens (2006) described how distressing disclosure experiences can silence survivors for many years. More information about different patterns of disclosure and the relationship of these patterns to adjustment would help guide program development for survivors.

Another important direction for future research is to develop theory-driven hypotheses about similarities and differences in the recovery process for diverse groups of women (Long, Ullman, Starzynski, Long, & Mason, 2007; Neville et al., 2004). Neville and colleagues examined a model that highlights the impact of cultural norms on attributions of responsibility for sexual assault and the importance of not assuming that all members of an ethnic group share the same beliefs. Long et al. found that age and education had strong effects on the recovery process of African American survivors. Their findings demonstrate the importance of defining diversity simultaneously across multiple aspects of identity.

Program Implications

Other people play an important role in sexual assault survivors’ recovery process. Confidants must respond with empathy and avoid responses that might be perceived as critical. Training programs are needed for formal providers, such as religious leaders, who may not be well informed about sexual assault. Survivors who most actively seek support may be the most distressed and most easily upset by an unintended negative remark. Although some individuals may intend to blame the victim, research suggests that others often mean well but do not know how to provide effective support (Herbert & Dunkel-Schetter, 1992). Service providers must also provide culturally appropriate services (Holzman, 1996; Russo & Vaz, 2001). For example, group sessions can increase distress among survivors who come from cultures that view rape as particularly shameful and private (Holzman, 1996). Clients need to feel welcome in the service setting in order to feel comfortable disclosing sensitive information. Sorenson (1996) found that when food and grooming supplies were not culturally congruent, interpersonal violence survivors felt unwelcome and did not stay.

Societal stereotypes about rape victims continue to encourage victim blame. Concerted efforts are needed to focus society’s attention on stopping perpetrators rather than blaming their victims. When survivors can count on receiving support rather than blame, sexual assault may no longer be a hidden secret.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by Grant R01AA011346 to Antonia Abbey from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A. Monique Clinton-Sherrod played an instrumental role in the development of the original study.

Contributor Information

Angela J. Jacques-Tiura, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Rifky Tkatch, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Antonia Abbey, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Rhiana Wegner, Department of Psychology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

References

- Abbey A, Andrews FM, Halman LJ. Provision and receipt of social support and disregard: What is their impact on the marital life quality of infertile and fertile couples? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:455–469. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, BeShears R, Clinton-Sherrod AM, McAuslan P. Similarities and differences in women’s sexual assault experiences based on tactics used by the perpetrator. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Parkhill MR. Sexual assault among diverse populations of women. In: Landrine H, Russo N, editors. Handbook of diversity in feminist psychology. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 391–425. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CE. Being silenced: The impact of negative social reactions on the disclosure of rape. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;38:263–274. doi: 10.1007/s10464-006-9069-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens CE, Campbell R, Ternier-Thames NK, Wasco SM, Sefl T. Deciding whom to tell: Expectations and outcomes of rape survivors’ first disclosures. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard R. Short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Psychological Reports. 1992;71:1155–1160. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3f.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borja SE, Callahan JL, Long PJ. Positive and negative adjustment and social support of sexual assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:905–914. doi: 10.1002/jts.20169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: A multisystems approach. New York: Guilford Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Broman-Fulks J, Ruggerio KJ, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, et al. Sexual assault disclosure in relation to adolescent mental health: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:260–266. doi: 10.1080/15374410701279701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Greeson MR, Bybee D, Raja S. The co-occurrence of childhood sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sexual harassment: A mediational model of post-traumatic stress disorder and physical health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:194–207. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Sefl T, Barnes HE, Ahrens CE, Wasco SM, Zaragoza-Diesfeld Y. Community services for rape survivors: Enhancing psychological well-being or increasing trauma? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:847–858. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153–160. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan R, Williams M. Living at the intersection: The effects of racism and sexism on black rape survivors. Women & Therapy. 2002;25:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JN, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Predicting PTSD in women with a history of childhood rape. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:573–588. doi: 10.1023/a:1024841718677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipas HH, Ullman SE. Social reactions to sexual assault victims from various support sources. Violence and Victims. 2001;16:673–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Daigle LE, Cullen FT, Turner MG. Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: Results from a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2003;30:6–38. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Tashiro T, Berman M, Steger M, Long J. Correlates of levels and patterns of positive life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:19–30. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM. Sexual-assault history and long-term physical health problems: Evidence from clinical and population epidemiology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1999;8:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM, Wilsnack SC, Cooper ML. Sexual assault history and social support: Six general population studies. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:187–197. doi: 10.1023/A:1015247110020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Novak SA, Lepore SJ, Eton DT. Spouse social control efforts: Relations to health behavior and well-being among men with prostate cancer. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2004;21:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert TB, Dunkel-Schetter C. Negative social reactions to victims: An overview of responses and their determinants. In: Montada L, Filipp S, Lerner MJ, editors. Life crises and experiences of loss in adulthood. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holzman CG. Counseling adult women rape survivors: Issues of race, ethnicity, and class. Women & Therapy. 1996;19:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JE, Davis RC, Taylor BG. Changes in spirituality and well-being among victims of sexual assault. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:322–328. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP. The hidden rape victim: Personality, attitudinal, and situational characteristics. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1985;9:193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, et al. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Long LM, Ullman SE, Starzynski LL, Long SM, Mason GE. Age and educational differences in African American women’s sexual assault experiences. Feminist Criminology. 2007;2:117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Masho SW, Ahmed G. Age of sexual assault and post-traumatic stress disorder among women: Prevalence, correlates, and implications for prevention. Journal of Women’s Health. 2007;16:262–271. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Heppner MJ, Oh E, Spanierman LB, Clark M. General and culturally specific factors influencing black and white rape survivors’ self-esteem. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Neville HA, Pugh AO. General and culture-specific factors influencing African Americans women’s reporting patterns and perceived social support following sexual assault: An exploratory investigation. Violence Against Women. 1997;3:361–381. doi: 10.1177/1077801297003004003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. The effects of traumatic disclosure on physical and mental health: The values of writing and talking about upsetting events. In: Violanti JM, Paton D, Dunning C, editors. Posttraumatic stress intervention: Challenges, issues, and perspectives. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce-Baker C. Surviving the silence: Black women’s stories of rape. New York: Norton; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LS. I will survive: The African-American guide to healing from sexual assault and abuse. New York: Seal Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Russo CF, Vaz K. Addressing diversity in the decade of behavior: Focus on women of color. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2001;25:280–294. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Briggs-Phillips M, Hobfoll SE. Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among inner-city women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:825–836. doi: 10.1002/jts.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorenson SB. Violence against women: Examining ethnic differences and commonalities. Evaluation Review. 1996;20:123–145. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9602000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starzynski LL, Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Townsend SM. Correlates of women’s sexual assault disclosure to informal and formal support sources. Violence and Victims. 2005;20:417–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JY. Taking back: Research as an act of resistance and healing for African American survivors of intimate male partner violence. Women & Therapy. 2002;25:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: Understanding the health consequences of relationships. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Social support and recovery from sexual assault: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1999;4:343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE. Mental health service seeking in sexual assault victims. Women & Therapy. 2007;30:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Predictors of PTSD symptom severity and social reactions in sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:369–389. doi: 10.1023/A:1011125220522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH, Towsend SM, Starzynski LL. Psychosocial correlates of PTSD symptom severity in sexual assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:821–831. doi: 10.1002/jts.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Starzynski LL, Long SM, Mason GE, Long LM. Exploring the relationships of women’s sexual assault disclosure, social reactions, and problem drinking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1235–1257. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Townsend SM, Filipas HH, Starzynski LL. Structural models of assault severity, social support, avoidance coping, self blame, and PTSD among sexual assault survivors. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Washington PA. Disclosure patterns of black female sexual assault survivors. Violence Against Women. 2001;7:1254–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner R, Abbey A, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Tkatch R. Manuscript submitted for publication. Cumulative and assault-specific correlates of posttraumatic stress symptoms among African American and Caucasian survivors of sexual assault. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weist MD, Pollitt-Hill J, Kinney L, Bryant Y, Anthony L, Wilkerson J. Sexual assault in Maryland: The African American experience. 2007 Retrieved June 10, 2009, from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/217617.pdf.

- West CM. Sexual violence in the lives of African American women: Risk, response, resilience. 2006 Retrieved June 10, 2009, from http://www.vawnet.org.

- Wyatt GE. The sociocultural context of African American and white American women’s rape. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48:77–91. [Google Scholar]