Fluorescent molecules are indispensable tools in modern biochemical and biological research, being used as labels for biomolecules, indicators for ions, stains for organelles, and substrates for enzymes.[1] The major targets of this last class are hydrolases that catalyze the removal of a masking moiety, thereby modulating fluorescence.[2] A critical property of fluorogenic hydrolase substrates is their chemical stability in aqueous solution, as spontaneous hydrolysis can compete deleteriously with enzymatic activity. New substrate classes that exhibit increased stability while maintaining enzymatic reactivity would be highly desirable.

Our laboratory recently reported on the use of the “trimethyl lock” strategy in the design of a latent fluorophore.[3] This latent fluorophore consists of a trimethyl lock component inserted between a dye and enzyme-reactive group. The trimethyl lock is an o-hydroxycinnamic acid derivative in which unfavorable steric interactions between three methyl groups encourage rapid lactonization to form a hydrocoumarin and release a leaving group.[4, 5] Our initial latent fluorophore exhibited remarkable stability in aqueous solution, but released a xanthene dye (rhodamine 110) upon hydrolytic cleavage by an esterase. Here, we explore the modularity of our design, probing its applicability to unrelated dyes that absorb at short (blue) and long (red) wavelengths.

Coumarin-based compounds comprise an important class of blue dyes possessing UV or near-UV excitation wavelengths.[6] Acyl esters and acyloxymethyl ethers of 7-hydroxycoumarin (i.e., umbelliferone) can be substrates for esterases.[7–9] 7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) is used widely as the basis for protease substrates.[10–12] Upon amidation, the excitation and emission wavelengths of AMC are shifted to shorter wavelengths with concomitant reduction in quantum yield.[10]

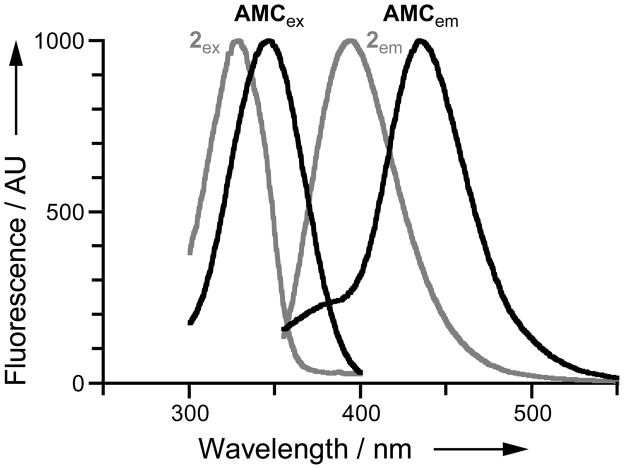

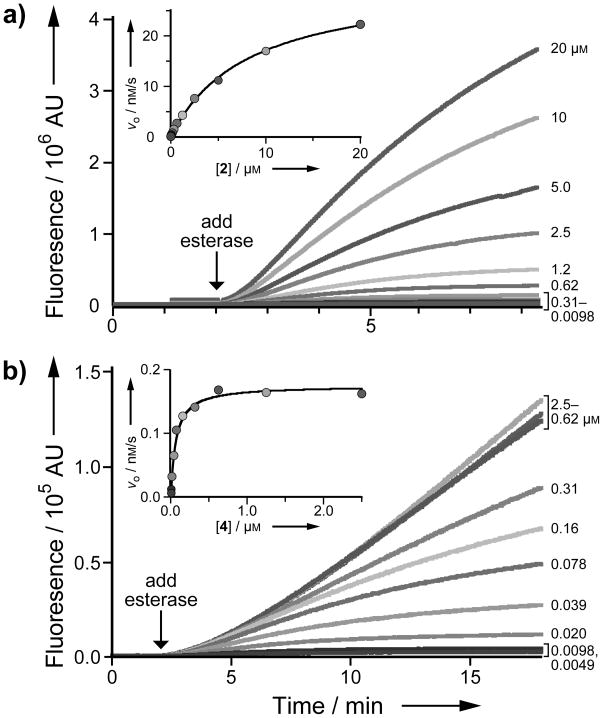

We reasoned that AMC could be subjected to our latent fluorophore strategy. Accordingly, we condensed AMC with acetylated trimethyl lock 1[13] to give pro-fluorophore 2 (Scheme 1), which displayed the expected hypsochromic shift of excitation and emission spectra relative to free AMC (Figure 1). The hydrolysis of profluorophore 2 was catalyzed by porcine liver esterase (PLE) with kcat/KM = 2.5 × 105 M−1s−1 and KM = 8.2 μM (Figure 2A). This kcat/KM value is 102-fold greater than the apparent kcat/KM value for the latent fluorophore based on rhodamine 110.[3] (We use the term “apparent” because full fluorescence manifestation requires the lactonization of two trimethyl lock moieties.[3])

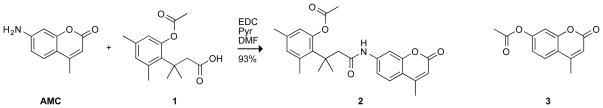

Scheme 1.

Route for the synthesis of pro-fluorophore 2, and the chemical structure of 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate (3).

Figure 1.

Normalized fluorescent excitation–emission spectra of pro-fluorophore 2 and AMC.

Figure 2.

(a) Kinetic traces (λex 365 nm, λem 460 nm) and Michaelis–Menten plot (inset) for the hydrolysis of pro-fluorophore 2 (20 μM→9.8 nM) by PLE (2.5 μg/mL); kcat/KM = 2.5 × 105 M−1s−1 and KM = 8.2 μM. (b) Kinetic traces (λex 586 nm, λem 620 nm) and Michaelis–Menten plot (inset) for the hydrolysis of pro-fluorophore 4 (2.5 μM→4.9 nM) by PLE (2.5 μg/mL); apparent kcat/KM = 1.2 × 105 M−1s−1 and apparent KM = 0.14 μM.

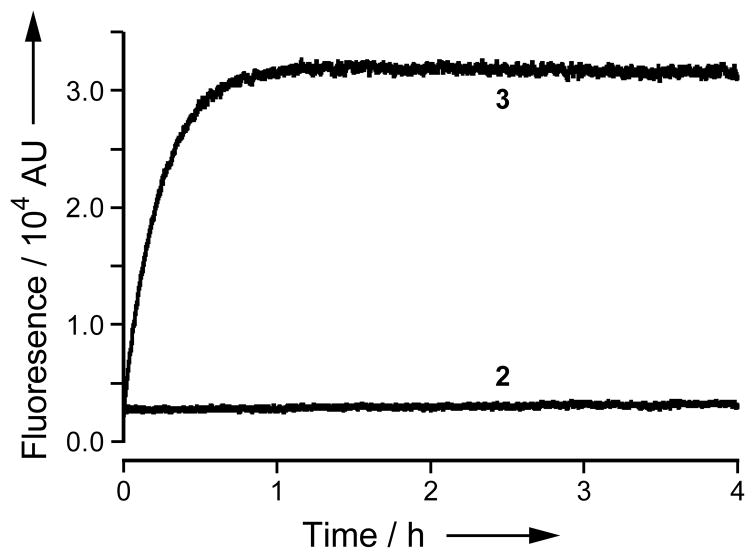

To evaluate the relative stability of pro-fluorophore 2, we monitored the accretion of fluorescence in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing bovine serum albumin (BSA; 1.0 mg/mL) and either pro-fluorophore 2 or 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate (3, which is a common esterase substrate[9]). Pro-fluorophore 2 proved to be highly stable compared to 4-methylumbelliferyl acetate (Figure 3). An additional advantage of pro-fluorophore 2 is that the product of its hydrolysis, AMC, shows little change in fluorescence at pH ≥ 5.[1] In contrast, the fluorescence of 4-methylumbelliferone is highly variable due to its pKa = 7.40[14] being near the physiological pH.

Figure 3.

Time course of the generation of fluorescence (λex 365 nm, λem 460 nm) from pro-fluorophore 2 (50 nM) or methylumbelliferyl acetate 3 (50 nM) in PBS containing BSA (1 mg/mL).

To access longer wavelengths, we turned to the oxazine class of red dyes. One such dye, cresyl violet (CV) has been used for decades to stain tissues[15, 16] and as a laser dye.[17] Although CV has a maximal absorbance at 586 nm, its fused benzo ring broadens its absorption spectrum[18] and thereby allows excitation with a variety of light sources. Diamide derivatives of CV are virtually nonfluorescent and thus useful in the production of fluorogenic protease substrates.[19–21]

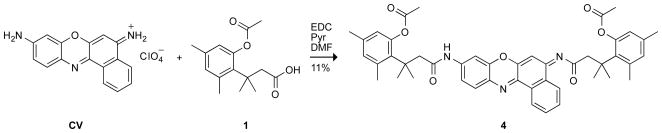

The attributes of CV make this dye an attractive candidate for our latent fluorophore strategy. Accordingly, we condensed CV with acetylated trimethyl lock 1[13] to give pro-fluorophore 4 (Scheme 2). Although pro-fluorophore 4 was stable in PBS containing BSA (data not shown), its hydrolysis was catalyzed by PLE with apparent kinetic parameters of kcat/KM = 1.2 × 105 M−1s−1 and KM = 0.14μM (Figure 2B). The kcat/KM value for the hydrolysis of pro-fluorophore 4 is similar to that of pro-fluorophore 2; the KM value is, however, 10-fold lower than that of pro-fluorophore 2.

Scheme 2.

Route for the synthesis of pro-fluorophore 4.

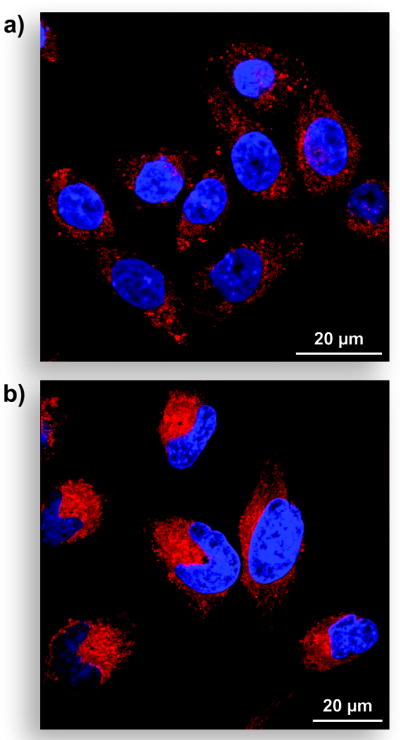

Pro-fluorophore 4 serves as a probe for esterase activity in live mammalian cells. The broad excitation peak allowed confocal microscopy experiments using excitation at 543 nm and emission at 605 nm. Pro-fluorophore 4 was hydrolyzed by esterases endogenous in the cells of a rodent (Figure 4A) or human (Figure 4B) to give a red-stained cytosol within minutes. The somewhat enhanced fluorescence observed in the human cells could be indicative of more efficient internalization or hydrolysis of the latent fluorophore. After longer incubation, the liberated CV became further localized in subcellular compartments (data not shown), which is consistent with previous reports.[21] To date, there have been few reports of long-wavelength esterase substrates that are useful in cell biology.[1] Its evident stability, optical properties, and fast intracellular eduction make pro-fluorophore 4 useful in a wide variety of biological applications, especially in assays involving fluorophores of different wavelengths.

Figure 4.

Unwashed mammalian cells incubated for 15 min with pro-fluorophore 4 (10 μM) at 37 °C in DMEM and counter-stained with Hoechst 33342 (5% v/v CO2(g), 100% humidity). (a) CHO K1 cells. (b) HeLa cells.

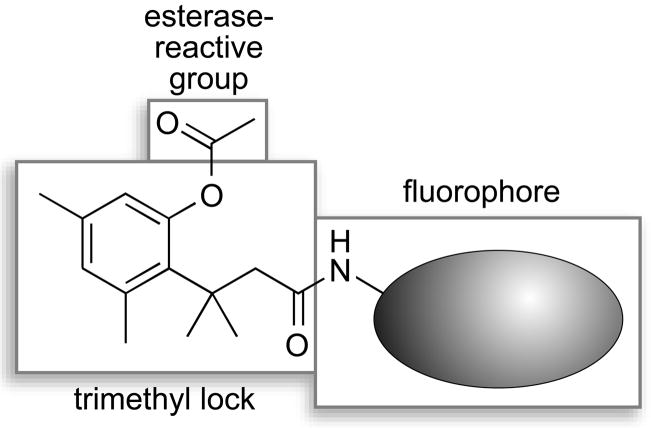

In conclusion, we have established that one component of our latent fluorophores—the dye—is modular (Figure 5). Specifically, we have now prepared useful latent fluorophores from three dyes (blue, green,[3] and red), all linked by a trimethyl lock moiety to an esterase-reactive group. In future work, we shall explore the modularity of the other component—the enzyme-reactive group. We anticipate that the end result will be a broad spectrum of stable latent fluorophores with numerous applications in biochemical and biological research.

Figure 5.

Modules in the latent fluorophores described in this work.

Experimental Section

AMC (i.e., Coumarin 440) and CV·HClO4 (i.e., Cresyl Violet 670 Perchlorate) were from Exciton (Dayton, OH). Dimethylformamide was drawn from a Baker CYCLE-TAINER™ solvent delivery system. All other reagents were from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, WI) or Fisher Scientific (Hanover Park, IL) and used without further purification.

PBS contained (in 1.00 L at pH 7.4) KCl (0.20 g), KH2PO4 (0.20 g), NaCl (8.0 g), and Na2HPO4·7H2O (2.16 g).

Thin-layer chromatography was performed using aluminum-backed plates coated with silica gel containing F254 phosphor and visualized by UV illumination or developed with I2, ceric ammonium molybdate, or phosphomolybdic acid stain. Flash chromatography was performed on open columns with silica gel-60 (230–400 mesh), or on a FlashMaster Solo system (Argonaut, Redwood City, CA) with Isolute® Flash Si II columns (International Sorbent Technology, Hengoed, Mid Glamorgan, UK).

NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker DMX-400 Avance spectrometer at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NMRFAM). Mass spectrometry was performed with a Micromass LCT (electrospray ionization, ESI) mass spectrometer in the Mass Spectrometry Facility in the Department of Chemistry.

7-Amino-4-methylcoumarin Trimethyl Lock (2)

AMC (53 mg, 0.304 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (2.0 mL) and anhydrous pyridine (1.0 mL). 3-(2′-Acetoxy-4′,6′-dimethylphenyl)-3,3-dimethylpropanoic acid[13] (1; 100 mg, 0.378 mmol) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC; 117 mg, 0.609 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 48 h. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, 0% to 40% v/v gradient of EtOAc in hexanes). Compound 2 was isolated as an off-white crystalline solid (119 mg, 93%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 7.66 (bs, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.21 (m, 2H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 6.65 (s, 1H), 6.15 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 2.55 (s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.36 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 172.51, 169.96, 161.13, 154.08, 152.17, 150.16, 141.56, 139.13, 137.40, 133.15, 132.82, 124.82, 123.46, 115.68, 115.27, 113.06, 106.65, 51.11, 40.53, 32.25 (2C), 25.49, 21.95, 20.15, 18.51. HRMS (ESI): m/z 444.1797 (MNa+ [C25H27NO5Na] = 444.1787).

Cresyl Violet Bis(trimethyl lock) (4)

CV·HClO4 (250 mg, 0.691 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (2.0 mL) and anhydrous pyridine (2.0 mL). 3-(2′-Acetoxy-4′,6′-dimethylphenyl)-3,3-dimethylpropanoic acid[13] (1, 394 mg, 1.38 mmol) and EDC (265 mg, 1.38 mmol) were added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 24 h. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was partitioned between CH2Cl2 and 5% v/v HCl(aq). The layers were separated, and the aqueous layer extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were washed with H2O and saturated brine, and dried over anhydrous MgSO4(s). Removal of solvent gave a brown solid that was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, 30% v/v EtOAc in hexanes). Compound 4 was isolated as a red-brown solid (55 mg, 11%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 8.57 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (bs, 1H), 7.65 (ddd, J = 8.0, 7.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (ddd, J = 7.9, 7.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (dd, 8.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.77 (m, 1H), 6.66 (m, 2H), 6.47 (m, 1H), 5.98 (s, 1H), 3.19 (s, 2H), 2.54 (s, 2H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 2.43 (s, 3H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.26 (s, 3H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 2.05 (s, 3H), 1.73 (s, 6H), 1.66 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 188.04, 172.79, 169.95, 169.91, 154.02, 150.21, 149.40, 147.92, 145.84, 144.77, 140.86, 139.24, 138.20, 137.37, 136.13, 133.48, 133.23, 132.88, 132.47, 132.13, 131.07, 130.77, 130.74, 129.49, 129.40, 125.56, 124.240, 123.41, 123.12, 115.63, 105.51, 101.12, 52.88, 51.15, 40.64, 39.34, 32.28 (2C), 32.06 (2C), 25.55, 25.33, 21.99, 21.88, 20.17, 20.10. HRMS (ESI): m/z 754.3471 (MH+ [C46H48N3O7] = 754.3492).

Fluoresence Spectroscopy

Fluorometric measurements were made with a QuantaMaster1 photon-counting spectrofluorometer from Photon Technology International (South Brunswick, NJ) equipped with sample stirring, and fluorescence grade quartz or glass cuvettes from Starna Cells (Atascadero, CA). All measurements were recorded at ambient temperature (23 ± 2 °C). Compounds were prepared as stock solutions in DMSO and diluted such that the DMSO concentration did not exceed 1% v/v. PLE (MW = 163 kDa[22]) was from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO; product number E2884) as a suspension in 3.2 M (NH4)2SO4, and was diluted to appropriate concentrations in PBS before use. Kinetic parameters were calculated with Microsoft Excel 2003 and GraphPad Prism 4.

Cell Preparation and Imaging

CHO K1 or HeLa cells were plated on Nunc Lab-Tek II 8-well Chamber Coverglass (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL) and grown to 70% confluence at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing fetal bovine serum (10% v/v). Cells were then incubated with pro-fluorophore 4 (10 μM) for 15 min at 37 °C and imaged immediately. Nuclear staining was accomplished by addition of Hoechst 33342 (2 μg/mL) for the final 5 min of incubation.

Cells were imaged with a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U confocal microscope equipped with a Zeiss AxioCam digital camera. Excitation at 408 nm was provided by a blue-diode laser, and emission light was passed though a filter centered at 450 nm with a 35-nm band-pass. Excitation at 543 nm was provided by a HeNe laser, and emission light was passed through a filter centered at 605 nm with a 75-nm band-pass.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to S.S. Chandran and Z. Diwu for contributive discussions. L.D.L. was supported by biotechnology training grant 08349 (NIH). This research was supported by grant CA73808 (NIH). NMRFAM was supported by grant P41RR02301 (NIH).

References

- 1.Haugland RP, Spence MTZ, Johnson ID, Basey A. The Handbook: A Guide to Fluorescent Probes and Labeling Technologies. 10. Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson I. Histochem J. 1998;30:123–140. doi: 10.1023/a:1003287101868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandran SS, Dickson KA, Raines RT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1652–1653. doi: 10.1021/ja043736v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borchardt RT, Cohen LA. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:9166–9174. doi: 10.1021/ja00781a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milstein S, Cohen LA. J Am Chem Soc. 1972;94:9158–9165. doi: 10.1021/ja00781a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valeur B. Molecular Fluorescence: Principles and Applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leroy E, Bensel N, Reymond JL. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2105–2108. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babiak P, Reymond JL. Anal Chem. 2005;77:373–377. doi: 10.1021/ac048611n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyatt JL, Stacy V, Wadkins RM, Yoon KJP, Wierdl M, Edwards CC, Zeller M, Hunter AD, Danks MK, Crundwell G, Potter PM. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5543–5550. doi: 10.1021/jm0504196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zimmerman M, Yurewicz E, Patel G. Anal Biochem. 1976;70:258. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(76)80066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita T, Kato H, Iwanaga S, Takada K, Kimura T. J Biochem. 1977;82:1495–1498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman M, Ashe B, Yurewicz EC, Patel G. Anal Biochem. 1977;78:47. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amsberry KL, Gerstenberger AE, Borchardt RT. Pharm Res. 1991;8:455–461. doi: 10.1023/a:1015890809507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graber ML, Dilillo DC, Friedman BL, Pastorizamunoz E. Anal Biochem. 1986;156:202–212. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banny TM, Clark G. Stain Technol. 1950;25:195–196. doi: 10.3109/10520295009110989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Culling CFA, Allison RT, Barr WT, Culling CFA. Cellular Pathology Technique. 4. Butterworths; Boston: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gacoin P, Flamant P. Optics Commun. 1972;5:351–353. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drexhage KH. In: Dye Lasers. 2. Schäfer FP, editor. Springer-Verlag; Berlin; New York: 1977. pp. 144–193. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Noorden CJ, Boonacker E, Bissell ER, Meijer AJ, van Marle J, Smith RE. Anal Biochem. 1997;252:71–77. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boonacker E, Elferink S, Bardai A, Fleischer B, Van Noorden CJF. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:959–968. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee BW, Johnson GL, Hed SA, Darzynkiewicz Z, Talhouk JW, Mehrotra S. BioTechniques. 2003;35:1080–1085. doi: 10.2144/03355pf01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horgan DJ, Dunstone JR, Stoops JK, Webb EC, Zerner B. Biochemistry. 1969;8:2006–2013. doi: 10.1021/bi00833a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]