Abstract

Proximate neural mechanisms that influence preferences for groups of a given size are almost wholly unknown. In the highly gregarious zebra finch (Estrildidae: Taeniopygia guttata), blockade of nonapeptide receptors by an oxytocin (OT) antagonist significantly reduced time spent with large groups and familiar social partners, independent of time spent in social contact. Opposing effects were produced by central infusions of mesotocin (MT; avian OT homologue). Most drug effects appear to be female-specific. Across five estrildid finch species, species-typical group size correlates with nonapeptide receptor distributions in the lateral septum, and sociality in female zebra finches was reduced by OT antagonist infusions into the septum but not a control area. We propose that titration of sociality by MT represents a phylogenetically deep framework for the evolution of OT’s female-specific roles in pair bonding and maternal functions.

Sociality, as defined by modal species-typical group size, is a core component of social organization that strongly impacts reproductive behavior, disease transmission, resource exploitation, and defense (1, 2). However, the neural mechanisms that titrate sociality and regulate the preference to live as singletons, in large groups, or somewhere in between are largely unknown. This likely reflects limited tractability, partly because the space requirements of large species-typical group sizes may be difficult to accommodate in experimental settings, and more importantly, because the behavioral dimension of sociality is difficult to isolate in comparative studies. For instance, because rodent species that differ in sociality also tend to differ in mating system, patterns of parental care, and other aspects of behavior and ecology that can influence neural and endocrine mechanisms associated with sociality (3, 4), comparative studies are not informative with respect to group size. Even in songbirds, which are speciose and socially diverse, only few opportunities exist for controlled comparisons, most notably in the family Estrildidae (finches, waxbills and munias; approximately 132 species total). All estrildid species are monogamous, exhibit long-term or life-long pair bonds, and show biparental care. However, even within specific ecological niches, estrildids display an extraordinary diversity in sociality, ranging from territorial male-female pairs to groups containing dozens or hundreds of colonially breeding pairs (5). This family includes the zebra finch, a socially tractable laboratory songbird (6).

In mammals, the neuropeptides arginine vasopressin (VP) and oxytocin (OT) influence numerous behavioral processes, including parental care, anxiety and monogamous pair bonding (7–11). Behavior may also be influenced in a sex-specific manner [e.g., pair bonding (12)], such that VP is required for a given behavior in males, but in females the same behavior is dependent upon OT. It has been postulated that separate nonapeptide clades giving rise to VP and OT originated due to a duplication of the arginine vasotocin (VT) gene in fish (13), and that sex-specific and affiliation-related nonapeptide functions date back to this duplication (14–16).

The major OT and VP cell groups in the mammalian brain are found in the preoptic area and hypothalamus and these populations are strongly conserved across the vertebrate classes, as are their central and hypophyseal projections (3, 17). In amniotes, OT-like peptide neurons are largely restricted to the hypothalamus, whereas homologous cell groups lie within the preoptic area of anamniotes (3). VT/VP cell groups are found in these same areas, although tetrapods also produce VT/VP in numerous extrahypothalamic parts of the brain, including the medial extended amygdala (bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; BSTm) (3). Most vertebrates (including birds) have multiple VT/VP receptor subtypes but only a single OT-like receptor (18).

Given that OT promotes bonding in mammals (7), we conducted experiments to test the hypothesis that endogenous MT promotes preferences for familiar conspecifics in birds. Zebra finches were housed in same-sex groups of six birds and individually tested for novel-familiar preferences by recording the amount of time subjects spent in close proximity to the five familiar cagemates versus five novel same-sex conspecifics (see diagram in Fig. 1A). We established behavioral effects using peripheral injections of the selective OT receptor antagonist desGly–NH2,d(CH2)5[Tyr(Me)2, Thr4]OVT [OTA; 5 μg subcutaneous, s.c. (19)] or saline, and on the basis of the the positive results of this experiment, we fitted finches with chronic guide cannulae and replicated the experiment using intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) infusions of OTA [250 ng; OTA and peptide dosages were used on the basis of previous experiments (15, 20)]. All tests were conducted with a within-subjects design and tests were spaced two days apart.

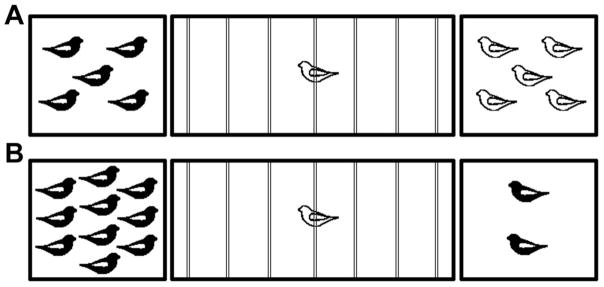

Fig. 1.

Choice apparatus design. A 1 m wide testing cage was subdivided into zones by seven perches (indicated by thin lines). Subjects were considered to be within close proximity when they were within 6 cm of a stimulus cage (corresponding to the perches closest to the sides). For novel-familiar choice tests (A), the two stimulus cages contained either five familiar cagemates or five unfamiliar individuals (all same-sex). For sociality tests (B), the stimulus cages contained either two or ten same-sex conspecifics. Sides were counterbalanced across subjects. Tests were 5 min and subject location was recorded at 15 sec intervals.

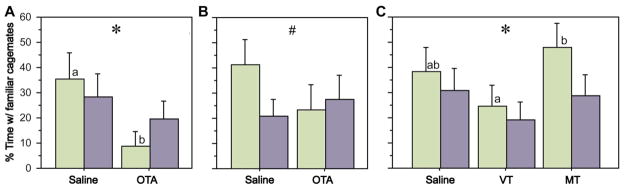

As predicted, peripheral administration of OTA significantly reduced the percent of time that subjects spent in close proximity to familiar cagemates (Fig. 2A). This effect is most pronounced in females, although significance is achieved only for the main effect of treatment (F1, 1, 21 = 3.833, P < 0.05, repeated-measures ANOVA). Central OTA infusions exerted a similar and significantly sex-specific effect (Fig. 2B; Sex x Treatment F1, 1, 20 = 4.019, P < 0.05). In contrast, central administrations of 50 ng MT, but not VT, tended to increase the time spent with familiar cagemates (Fig. 2C; main effect of Treatment F1, 2, 20 = 3.900, P < 0.05) especially for females, although the main effect of treatment in this experiment appears to come from the difference between VT and MT. Despite weak trends, no treatment effects were observed in any of these experiments for the percent of time spent with novel conspecifics (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Zebra finches were tested in a novel-familiar choice paradigm (as in Fig. 1A) following administrations of OTA and nonapeptides. Females and males are shown in green and purple, respectively. (A) OTA delivered s.c. significantly reduces time spent in close proximity to familiar same-sex cagemates (*P < 0.05, main effect of Treatment; n = 12 m, 11 f). Significant pairwise comparisons within a sex are indicated by different letters above the bars. Error bars indicate mean ± Standard error (SE) (B) A similar result is observed following i.c.v. infusions of OTA, although a significant Sex x Treatment interaction is obtained (#P < 0.05; n = 11 m, 11 f). (C) Central infusions of MT and VT differentially influence time spent with familiar cagemates (*P < 0.05, main effect of Treatment; n = 11 m, 11 f). Corresponding data for time spent in close proximity to novel conspecifics is provided in the SOM.

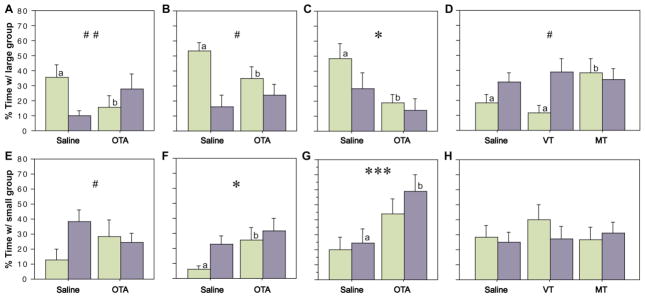

We tested the hypothesis that endogenous MT promotes sociality using the same apparatus as above, but rather than being exposed to novel and familiar conspecifics, subjects were exposed to a group of two same-sex conspecifics at one end of the testing cage and a group of ten same-sex conspecifics at the other end (as in Fig. 1B). In the first two experiments, subjects received OTA or saline s.c. and were exposed to groups of either novel conspecifics (Fig. 3A) or familiar conspecifics (Fig. 3B). For this latter experiment, stimulus animals were housed in a cage immediately adjacent to the subject’s cage for a minimum of five days prior to testing. Significant Sex x Treatment interactions were obtained in both experiments, with OTA reducing the percent of time that female subjects spent in close proximity to the large group (F1, 1, 21 = 8.426, P < 0.01 and F1, 1, 22 = 4.871, P < 0.05, respectively, repeated-measures ANOVA). Central infusions of OTA produced similar results (with novel conspecifics), although only a main effect of treatment was observed (Fig. 3C; F1, 1, 22 = 6.704, P < 0.05). Finally, VT and MT were administered i.c.v. and subjects were exposed to novel same-sex conspecifics. As predicted by the OTA findings, a significant Sex x Treatment interaction was obtained, due to a female-specific increase in time with the large group following infusions of MT (Fig. 3D; F1, 2, 31 = 3.021, P < 0.05). Across these four experiments, time with the small group tended to be inversely related to time with the large group (Fig. 3E–H).

Fig. 3.

Zebra finches were tested in a group size choice paradigm (as in Fig. 1B) following administrations of OTA and nonapeptides. The percent of time spent in close proximity to the large group is shown in panels A–D. Corresponding data for time spent in close proximity to the small group are shown directly below in panels E–H. Females and males are shown in green and purple, respectively. (A, E) OTA delivered s.c. significantly reduces the percent of time spent in close proximity to the large group in sociality tests with unfamiliar social partners, but only in females. This pattern is reversed for time spent in close proximity to the small group (#P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, Sex x Treatment interaction; n = 12 m, 11 f). Significant pairwise comparisons within a sex are indicated by different letters above the bars. Error bars indicate mean ± SE. (B, F) Similar results are obtained using familiar social partners (#P < 0.05, Sex x Treatment interaction; *P < 0.05, main effect of Treatment; n = 12 m, 12 f). (C, G) Central OTA infusions decrease time in close proximity to the large group and increase time in close proximity to the small group (tests conducted with unfamiliar social partners; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, main effect of Treatment; n = 12 m, 12 f). (D) Central infusions of MT, but not VT, produce a female-specific increase in the percent of time in close proximity to the large group (tests conducted with unfamiliar social partners; #P < 0.05, Sex x Treatment interaction; n = 17 m, 16 f).

These findings demonstrate that nonapeptide receptors influence group-size choices in zebra finches, and suggest the hypothesis that evolution in sociality is mediated, at least in part, by selection on the distribution of these receptors. In order to test this hypothesis, we quantified binding of an I125-labeled ornithine vasotocin analog (OVTA) in tissue sections from five species of estrildid finches. Two of these species are highly gregarious and breed colonially (zebra finch and spice finch, Lonchura punctulata); two are highly territorial and live as male-female pairs year-round (melba finch, Pytilia melba, and violet-eared waxbill, Uraeginthus granatina); and one is moderately gregarious (Angolan blue waxbill, U. angolensis). Other than sociality, these species are generally similar in other aspects of behavior and ecology (3–5, 21).

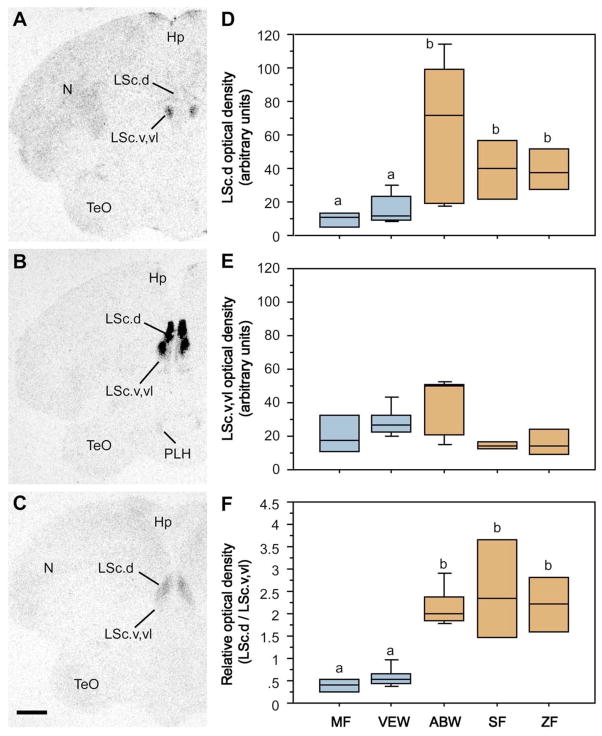

We observed binding sites for I125-OVTA in numerous forebrain areas, including the medial striatum, mediobasal hypothalamus, and lateral septum (LS), consistent with other passerines (22). Of these, the LS is of particular interest in relation to sociality (3), and this is the only area where binding densities correlated with differences in sociality across species. All three of the gregarious (i.e., flocking) species exhibited significantly higher binding densities in the dorsal (pallial) zone of the caudal LS (LSc) than the two territorial species (Fig. 4A–D; Kruskal-Wallis H = 13.682, P < 0.01), but this direction of species differences tends to reverse within the ventral and ventrolateral (subpallial) zones of the LSc (Fig. 4E; H = 8.994, P = 0.06), suggesting that the relative concentrations of binding sites along the dorso-ventral axis of the LSc may be an important determinant of sociality. Indeed, flocking and territorial species were most clearly differentiated when dorsal and ventral binding densities were expressed as a difference measure (not shown) or as a ratio (dorsal/ventral; Fig. 4F; H = 16.648, P < 0.01). No sex differences were observed (all P > 0.5).

Fig. 4.

I125-OVTA binding sites in the LS differentiate territorial and flocking finch species. (A–C) Representative autoradiograms of binding sites in two sympatric congeners – the territorial violet-eared waxbill (A) and the gregarious Angolan blue waxbill (B), plus the highly gregarious zebra finch (C). (D) Densities of I125-OVTA binding sites in the dorsal (pallial) LSc of two territorial species (melba finch, MF, and violet-eared waxbill, VEW), a moderately gregarious species (Angolan blue waxbill, ABW), and two highly gregarious species (spice finch, SF, and zebra finch, ZF). Territorial and flocking species are shown in blue and orange, respectively. No sex differences are observed and sexes were pooled. Total n = 23 (see SOM text). Different letters above the boxes denote significant species differences (Mann-Whitney P < 0.05) following significant Kruskal-Wallis. Box plots show the median (line), 75th and 25th percentile (box) and 95% confidence interval (whiskers). (E) Binding densities tend to reverse in the subpallial LSc (Kruskal-Wallis P = 0.06), suggesting that species differences in sociality are most closely associated with the relative densities of binding sites along a dorso-ventral gradient, as confirmed in the bottom panel (F). Abbreviations: Hp, hippocampus; LSc.d, dorsal zone of the caudal lateral septum; LSc.v,vl, ventral and ventrolateral zones of the caudal lateral septum; N, nidopallium; PLH, posterolateral hypothalamus; TeO, optic tectum.

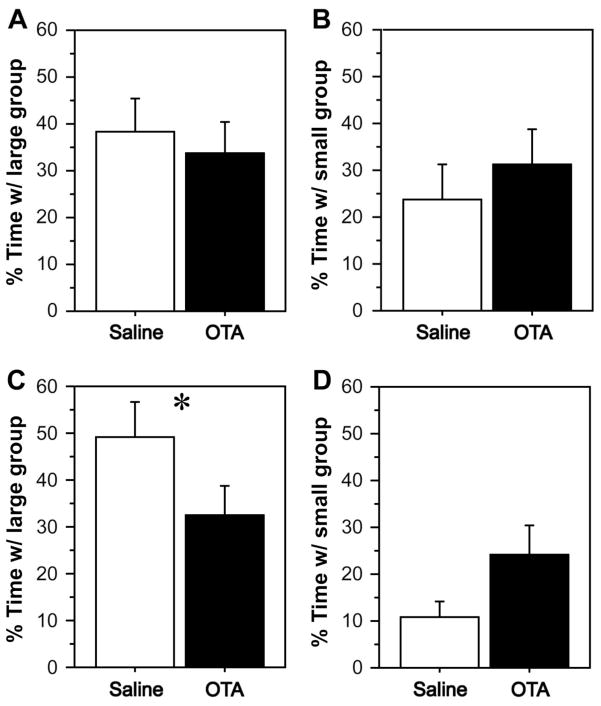

In order to directly demonstrate that OT-like binding sites in the LS influence sociality, we fitted female zebra finches with guide cannulae directed at the LS or telencephalic control areas adjacent to the lateral ventricle, and conducted sociality tests following infusions of OTA or saline, as described above. Infusions into telencephalic control areas produced no significant effects (Fig. 5A–B). However, as predicted, intraseptal administration of OTA significantly reduced the amount of time that subjects spent in close proximity to the large group (Fig. 5C; P < 0.05, paired t-test), and tended to increase the time spent with the small group (Fig. 5D; P = 0.08).

Fig. 5.

Female zebra finches were tested in a group size choice paradigm (as in Fig. 1B) following administrations of OTA or saline into the LS or telencephalic control regions adjacent to the lateral ventricle. (A–B) OTA infusions into telencephalic control regions produced no signficant effect on time spent with the large group (A) or the small group (B). (C–D). OTA infusions into the LS significantly reduced time with the large group (*P < 0.05; panel C) and tended to increase time with the small group (P = 0.08; panel D). Error bars indicate mean ± SE.

Previous experiments (immediate early gene, lesion and peptide binding studies) (3) likewise suggest that the LS is a focal point of neural processes that titrate sociality, and species differences in sociality are strongly and positively related to the density of V1a-like binding sites throughout the LS complex (4). VT/VP and V1a-like receptors play important roles in stress, aggression and affiliation behaviors across vertebrate taxa (3, 10), and the VT cells of the BSTm (which project heavily to the LS) increase their immediate early gene activity selectively in response to affiliation-related social stimuli (23). The lack of VT effects observed here is therefore surprising. However, it is important to note that VT neurons in the BSTm are functionally opposed to those in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) (3), and thus VT effects are apt to depend upon specific patterns of release across brain areas, which are not readily mimicked by i.c.v. infusions.

OT release in mammals reduces anxiety (24) and promotes social recognition (25, 26), monogamous partner preferences (12, 27), trust (28), and maternal behaviors (7–11), including maternal aggression (29). Limited behavioral functions of OT homologues have also been established for teleost fish (15, 16), but comparable data have been wholly absent for MT. The present findings suggest that affiliative functions are conserved for the OT-like nonapeptides, although total proximity time (time at both ends of the test cage combined) was not significantly affected by treatments in any of our seven behavioral experiments (all P > 0.10; data not shown). Rather, treatments selectively influenced social preferences, and overall, our findings suggest that the activation of nonapeptide receptors by endogenous MT promotes sociality (preferences for larger groups) and the preference for familiar social partners. Thus, the combined findings that isotocin modulates social communication and approach in fishes (15, 16), and that MT promotes sociality in birds (present data), strongly suggest that OT-like peptides have influenced social groupings for most of verebrate history.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to the memory of R. A. Zann, who inspired us through his work. Funded by NIH MH062656 (study section on Biobehavioral Regulation, Learning and Ethology) to J.L.G.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Krause J, Ruxton GD. Living in groups. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silk JB. Philos Trans R Soc B-Biol Sci. 2007;362:539. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodson JL. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:3. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodson JL, Evans AK, Wang Y. Horm Behav. 2006;50:223. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodwin D. Estrildid finches of the world. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zann RA. The zebra finch: a synthesis of field and laboratory studies. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter CS, Grippo AJ, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Ruscio MG, Porges SW. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:331. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Landgraf R, Neumann ID. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25:150. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leng G, Meddle SL, Douglas AJ. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:731. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim MM, Young LJ. Horm Behav. 2006;50:506. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veenema AH, Neumann ID. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:261. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Insel TR, Hulihan TJ. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:782. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acher R, Chauvet J, Chauvet MT. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;395:615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donaldson ZR, Young LJ. Science. 2009;322:900. doi: 10.1126/science.1158668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodson JL, Bass AH. Nature. 2000;403:769. doi: 10.1038/35001581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson RR, Walton JC. Behav Neurosci. 2004;118:620. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.3.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries GJ, Buijs RM. Brain Res. 1983;273:307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baeyens DA, Cornett LE. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;143:12. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cushing BS, Carter CS. Horm Behav. 2000;37:49. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodson JL, Lindberg L, Johnson P. Horm Behav. 2004;45:136. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skead DM. Ostrich. 1975;supp 11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung CH, Goode CT, Young LJ, Maney DL. J Comp Neurol. 2009;513:197. doi: 10.1002/cne.21947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodson JL, Wang Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606278103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirsch P, et al. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choleris E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700670104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson JN, Aldag JM, Insel TR, Young LJ. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08278.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross HE, et al. J Neurosci. 2008;29:1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5039-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Neuron. 2008;58:639. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosch OJ, Meddle SL, Beiderbeck DI, Douglas AJ, Neumann ID. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1342-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris D. Proc Zool Sci Lond. 1958;131:389. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.