Abstract

Objective

Tongue movement is temporo-spatially coordinated with jaw and hyoid movements during eating and speech. As such, we evaluated 1) the correlation between the tongue with jaw and hyoid movements during eating and speech and 2) the relative influence of the jaw and hyoid on determining tongue movement.

Design

Lateral projection videofluorography was recorded while 16 healthy subjects ate solid foods or read a standard passage. The position of anterior and posterior tongue markers (ATM and PTM, respectively), the jaw, and the hyoid relative to the upper occlusal plane was quantified with the upper canine as the origin (0,0) point for Cartesian coordinates. For vertical and horizontal dimensions, separate multiple linear regression analyses were performed with ATM or PTM position as a function of jaw and hyoid positions.

Results

Vertically, both ATM and PTM positions were highly correlated with the jaw and hyoid during eating (median r = 0.87). The relative influence was higher for the jaw than the hyoid for ATM position (P < 0.001), but lower for PTM position (P = 0.04). Horizontally, tongue marker positions had moderate correlation with the jaw and hyoid during eating (r = 0.47), due more to hyoid position than to jaw position. Overall, correlations were lower during speech than eating.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated distinct kinematic linkages between the movements of the jaw, the hyoid and the anterior and posterior tongue markers, as well as differing impact of the jaw and the hyoid in determining tongue movement during eating and speech.

Keywords: eating, speech, tongue, jaw, hyoid, regression analysis

INTRODUCTION

The musculature of the tongue consists of extrinsic and intrinsic components; the former have mechanical connections to the mandible, hyoid, and cranial base, while the latter contain sets of intralingual muscle fiber bundles without connections to bony tissue. During feeding and speech, the coordinated actions of intrinsic and extrinsic tongue muscles produce a variety of movements and deformations of the isovolumic tongue.1–3

The relationship of tongue movement with jaw movement in human eating and speech has been widely studied with different techniques.2, 4–7 Palmer et al. visualized the movements of the tongue and jaw in human feeding using videofluorography (VFG) with small radiopaque markers glued to the tongue and teeth, 5 and confirmed that the movement of the tongue was temporally linked to jaw movement in human eating. Tongue-jaw coordination has also been confirmed by studies using electromagnetic articulography or X-ray microbeam. 8–11 The movement of the lower jaw has a significant influence on tongue movement since the tongue rides on the floor of the mouth through a physical muscle connection. During both eating and speaking the tongue can also move independently of any concurrent movement of the mandible, because of the action of the intrinsic muscles.6, 12

The tongue also has a major muscle connection to the hyoid bone so that during eating, cyclic hyoid movement facilitates tongue movement in mastication, oral-pharyngeal food transport, and swallowing.5, 13–16 During speech, on the other hand, the influence of the hyoid bone on tongue motion remains unclear.17–19 Hiiemae et al. reported that the hyoid bone moved continuously during both eating and speech, although the spatial domain of hyoid movement was significantly different in the two behaviors. Their findings suggested that the hyoid served different functions during eating and speech.19

During eating or speech, the tongue’s movement is associated with the jaw and hyoid bones through physical connections, but it can also move and deform independently via its intrinsic muscle contractions. However, little is known about how much tongue positioning is determined by the positions of the jaw and hyoid during these actions. Furthermore, different parts of the tongue might have different associations with other structures. Thus, our purpose was 1) to determine how far the movements of markers on the tongue surface were temporo-spatially correlated with movements of the jaw and hyoid bone during eating and speech, and 2) to quantify the relative influence of jaw and hyoid position in determining the positions of different parts of the tongue.

In the present study, we applied a multiple linear regression model to test the above hypotheses. Multiple linear regression analysis is generally used to quantify mechanics among multiple factors.20, 21 This function provides correlation coefficients, which reflect the association among factors, as well as partial regression coefficients, which indicate the relative influence of each factor in determining the dependent variable. Throughout this study, we assumed that our results also indirectly reflected the degree of neural control of the activities of the tongue, jaw, and hyoid during eating and speech.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The protocol of this study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Johns Hopkins University. Sixteen healthy young adult volunteers (mean ± SD age, 21.8 ± 1.7 years, 7 male and 9 female) participated after giving verbal and written informed consent. All participants were in excellent health and had no history of major medical or dental problems or dysphagia. All participants had Class I occlusion.

Data collection

Data collection was performed using experimental protocols and VFG recording techniques as described previously.5, 19

For VFG recordings, small lead discs (4 mm in diameter and 0.5 mm thick) were used as radiopaque markers to quantify tongue surface and jaw movement. The discs were glued to the dried dorsal tongue surface approximately 10 mm posterior from the tongue tip on the midline (anterior tongue marker; ATM) and as posterior as possible along the midline (posterior tongue marker; PTM) with a dental adhesive cement (Ketac, ESPE-Premier Sales Corp., Norristown, PA) (Fig. 1). The distance between the two tongue markers at rest was approximately 15 mm. Markers were also cemented to the buccal surface of the left upper and lower canines and upper first molar.

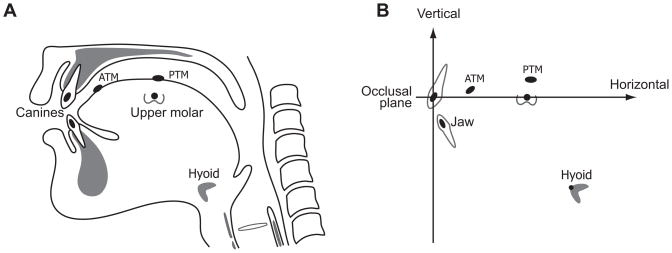

Figure 1.

Locations of the jaw, hyoid, and anterior and posterior tongue markers and their positions in Cartesian coordinates. (A) Small lead discs were glued to the dried dorsal tongue surface approximately 10mm posterior from the tongue tip along the midline (anterior tongue marker; ATM) and as posteriorly as possible along the midline (posterior tongue marker; PTM). Radiopaque lead markers (5mm diameter) were also cemented to the buccal surfaces of the left upper and lower canines and upper first molar. (B) The positions of the ATM, PTM, jaw and hyoid (the antero-superior corner of the hyoid bone) were expressed as X (horizontal) and Y (vertical) coordinates relative to the upper occlusal plane defined by a line passing through the upper canine and first molar markers. The vertical axis was defined as the line perpendicular to the upper occlusal plane at the upper canine.

Lateral projection VFG was recorded on an S-VHS video recorder at 30 frames/sec while the subjects ate three solid foods (8g each of banana, chicken spread, and shortbread cookie) or read part of the “Grandfather Passage”.22 This text is commonly used in speech evaluation since it contains most of the vowel-consonant combinations used in the English language. Foods were given from soft to hard because markers on the tongue surface often detach during feeding, especially with hard food.5 If markers became detached, they were replaced and trials were re-recorded as long as VFG recording time did not exceed 5 minutes. One recording was taken for each behavior, and recordings for speech were performed in 10 subjects (Table 1). Previous studies have indicated that the effect of the tongue markers on eating and speech behavior is negligible.19

Table 1.

Summary of missing data

| Subject No. | Eating |

Speaking | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banana | Chicken | Cookie | ||

| 1 | no PTM | no PTM | ||

| 2 | PTM early off* | |||

| 3 | ATM, PTM off** | no recording | ||

| 4 | ATM, PTM off** | |||

| 5 | no recording | |||

| 6 | ATM off** | |||

| 7 | PTM off** | |||

| 8 | no recording | |||

| 9 | ATM, PTM off** | |||

| 10 | ||||

| 11 | ||||

| 12 | no PTM | no recording | ||

| 13 | ATM, PTM early off* | no PTM | no recording | |

| 14 | no recording | |||

| 15 | ||||

| 16 | ||||

| Total | 14 | 16 | 12 | 10 |

Recording data was not used for analysis due to early detachment of the marker.

Recording data was partially used for analysis despite the marker(s) detaching from the tongue surface.

Data reduction

VFG recordings on S-VHS tapes were imported onto a desktop computer with digital image processing software (Scion image, Scion Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). Whenever possible, complete eating or speaking sequences were used for analysis. The tongue markers occasionally detached from the tongue during or between VFG recordings (Table 1). If the marker came off the tongue surface early on in a cycle, the recording was not included in the analysis. If the marker came off at a later cycle stage, we used the data taken just before the jaw motion cycle where the marker became detached for analysis. Consequently, 52 behavior sequences were available for statistical analysis.

Every frame of the videofluorographic images was analyzed, and the raw X-Y coordinates for the following data points were manually acquired frame-by-frame on image processing software: Anterior and Posterior tongue markers (ATM and PTM, respectively), the upper canine and first molar, the lower canine (jaw), and the antero-superior corner of the hyoid bone (hyoid). To determine the movements of these structures, positional data were expressed in Cartesian coordinates relative to the upper occlusal plane (Fig. 1). The upper occlusal plane was defined as a line passing through the upper canine and first molar markers, and was used as the horizontal reference line (X-axis). The upper canine marker was set as the zero point. The vertical reference line (Y-axis) was defined as the line perpendicular to the X-axis crossing at the upper canine.5

Data analysis

To minimize high frequency cursor positioning errors in data acquisition, T4253H low pass filtering was performed using SPSS 14.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). This nonlinear algorithm is robust against long-tailed noise distributions and resistant to brief spikes.23

For each subject, a separate multiple linear regression analysis was performed on the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the movements produced during speech and eating. We set the position of the ATM or PTM as the dependent variable and the positions of the jaw and hyoid as the independent variables. In the regression model, correlation coefficients (r) and standardized partial regression coefficients (β) were calculated. Values for r represented how much the position of the ATM or PTM was temporo-spatially associated with the positions of the jaw and hyoid. β values represented the relative influence of jaw or hyoid position on determining the location of the tongue markers. A high absolute β value was indicative of a high degree of influence.

Fisher’s z transformation was performed to normalize each coefficient value before statistical analysis. 20 Repeated measured ANOVA was performed for horizontal and vertical dimensions to test for differences in the averaged coefficients (r or β). Independent variables for r were tongue marker position (ATM and PTM), behavior (eating three foods and speech) and their interaction. Independent variables for β were factor (jaw and hyoid), behavior (eating three foods and speech) and their interaction. Tukey’s test was used for post-hoc multiple comparisons.

Statistical procedures were performed with SPSS 14.0 software. The critical value of α for rejecting the null hypothesis was 0.05.

RESULTS

Vertical dimension

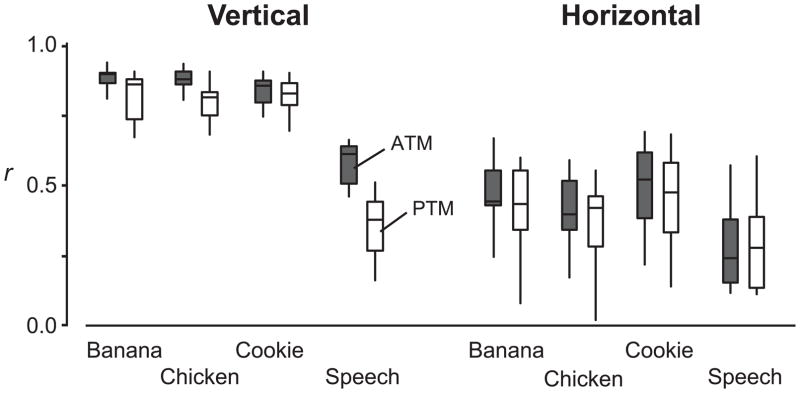

The correlation coefficients of all regression models were statistically significant. During eating, the positions of both the ATM and PTM were highly correlated with jaw and hyoid positions in the vertical dimension (median r = 0.89 for ATM and 0.84 for PTM) (Fig. 2 (representative case), Table 2, and Fig. 3). During speech, the r values were high for ATM (median r = 0.66) and moderate for PTM (median r = 0.43) (Table 2 and Fig. 3). There was an interaction effect between the vertical movement of markers and behavior type (P = 0.038). Values for r were lower in speech than in eating for both ATM and PTM markers (P < 0.001), and no significant differences in r were witnessed among food types. Overall, r was greater for ATM than for PTM during eating and speech (P < 0.001).

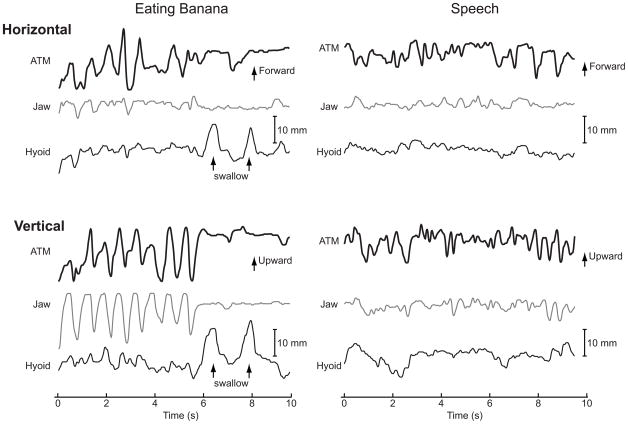

Figure 2.

Representative measurements of the movements of the anterior tongue marker (ATM), jaw, and hyoid in the horizontal and vertical dimensions over time. The complete sequence of eating banana is shown on the left, and the reading of a part of the “Grandfather Passage” by the same subject is on the right. Movement at the top of each figure is either forward or upward. During eating of banana, the ATM moves cyclically in horizontal and vertical dimensions. ATM movement was moderately correlated with jaw and hyoid movement in the horizontal dimension (r = 0.45) and highly correlated in the vertical dimension (r = 0.85). In contrast, the amplitude of structure movements was relatively small and movement patterns were more irregular during speech, which are reflected by lower correlation coefficients (r = 0.35 for the horizontal dimension and r = 0.64 for the vertical dimension).

Table 2.

Average correlation coefficients (r) and standardized partial regression coefficients (β) for each behavior in horizontal and vertical dimensions (median, interquartile range) in the multiple regression model. The position of the ATM or PTM was set as the dependent variable and the positions of the jaw and hyoid were set as the independent variables.

| Banana | Chicken | Cookie | Speech | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal | |||||

| ATM | |||||

| r | 0.45 (0.44–0.56) | 0.41 (0.35–0.53) | 0.53 (0.39–0.63) | 0.25 (0.16–0.43) | |

| β | Jaw | 0.02 (−0.14–0.20) | 0.00 (−0.12–0.18) | 0.00 (−0.09–0.10) | 0.07 (−0.14–0.24) |

| Hyoid | 0.44 (0.31–0.48) | 0.37 (0.22–0.53) | 0.51 (0.34–0.59) | 0.14 (0.04–0.29) | |

| PTM | |||||

| r | 0.44 (0.34–0.56) | 0.43 (0.29–0.47) | 0.48 (0.30–0.60) | 0.29 (0.14–0.41) | |

| β | Jaw | −0.13 (−0.32–0.06) | −0.13 (−0.25–0.06) | −0.18 (−0.28–0.02) | 0.14 (−0.07–0.24) |

| Hyoid | 0.43 (0.33–0.50) | 0.34 (0.18–0.52) | 0.57 (0.21–0.59) | 0.13 (0.04–0.31) | |

| Vertical | |||||

| ATM | |||||

| r | 0.90 (0.86–0.90) | 0.88 (0.86–0.91) | 0.86 (0.80–0.88) | 0.62 (0.50–0.65) | |

| β | Jaw | 0.75 (0.66–0.78) | 0.74 (0.65–0.80) | 0.64 (0.55–0.69) | 0.56 (0.44–0.63) |

| Hyoid | 0.29 (0.22–0.38) | 0.35 (0.21–0.38) | 0.33 (0.22–0.40) | 0.09 (0.03–0.17) | |

| PTM | |||||

| r | 0.86 (0.74–0.88) | 0.82 (0.75–0.84) | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | 0.38 (0.24–0.45) | |

| β | Jaw | 0.41 (0.31–0.58) | 0.33 (0.29–0.53) | 0.39 (0.24–0.53) | 0.25 (0.15–0.41) |

| Hyoid | 0.46 (0.42–0.68) | 0.58 (0.45–0.70) | 0.60 (0.47–0.64) | 0.14 (0.07–0.21) | |

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plots showing the average multiple correlation coefficients (r) by behavior (eating each food, speaking) and anterior and posterior tongue markers (ATM and PTM, respectively) in the vertical and horizontal dimensions. In the vertical dimension, ATM and PTM positions were highly correlated with jaw and hyoid positions during eating, with the average r higher for ATM than for PTM. Vertical correlations were higher during eating than speaking. In the horizontal dimension, the ATM and PTM positions were moderately correlated with jaw and hyoid positions in the multiple regression model.

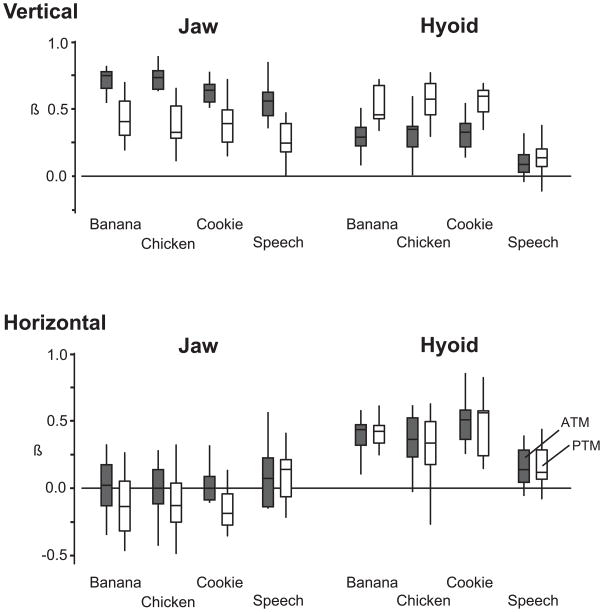

During eating, the β was higher for the jaw than the hyoid for ATM (P < 0.001), but was higher for the hyoid than the jaw for PTM (P = 0.042) (Fig. 4). During speech, the β of the jaw was high for ATM but not for PTM, and the β of the hyoid was low for both ATM and PTM positions (Fig. 4). The β was significantly higher for both the jaw and hyoid during eating than speech (P < 0.001). There was no significant interaction effect between the factor (jaw and hyoid) and behavior type for ATM and PTM positions. There were no significant β differences among food types, except for one between chicken spread and cookie for ATM position (P = 0.011).

Figure 4.

Box and whisker plots showing the average standardized partial correlation coefficients (β) by factor (jaw and hyoid), behavior (eating each food, speaking), and anterior and posterior tongue markers (ATM and PTM, respectively) in the vertical and horizontal dimensions. In the vertical dimension, jaw β was higher for ATM position during eating, but hyoid β was higher for PTM position. In the horizontal dimension during eating, β was higher for the hyoid than the jaw for both ATM and PTM positions. During speech, β was generally low except for vertical jaw position.

Horizontal dimension

During eating, tongue marker positions were moderately correlated with jaw and hyoid positions in the horizontal dimension (median r = 0.47 for ATM and 0.46 for PTM). During speech, correlation with the jaw and hyoid was low (median r = 0.25 for ATM and 0.29 for PTM) (Table 2 and Fig. 3). There was no significant interaction effect between the marker and behavior type. The average r values were statistically different among behavior types (P = 0.038), but post hoc tests showed a notable r difference between cookie eating (median r = 0.53) and speech (r = 0.25, P = 0.030) only. There was no significant r difference between ATM and PTM for any behavior type (P = 0.096).

β values in the horizontal dimension were quite different from those in the vertical dimension; the β of the hyoid was high for both ATM and PTM positions in eating, but the β of the jaw was significantly lower (P < 0.001). During speech, the β of the hyoid and jaw were both generally low.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to 1) determine how much the movement of the tongue surface was temporo-spatially correlated with the movements of the jaw and hyoid bone during eating and speech and 2) quantify the relative influence of jaw and hyoid positions in determining the positions of different parts of the tongue. In our multiple linear regression model, we revealed that the movements of the ATM and PTM had different correlations with the movements of the jaw and hyoid during eating and speech. These statistical associations may reflect the diverse coordination patterns of the anterior and posterior parts of the tongue with jaw and hyoid movements during these actions; a high correlation indicates strong kinematic coordination of the tongue with the jaw and hyoid, where the physical muscle connections among the structures may create tight temporo-spatial cohesion. In contrast, a low correlation indicates increased independent tongue motion and deformation from jaw or hyoid movement produced mainly by tongue intrinsic muscle activity.

In our multiple regression models, tongue positioning could be determined from the positions of the jaw and hyoid. However, because the tongue, jaw, and hyoid are connected to each other through their musculature, tongue activity may in fact affect hyoid and jaw positioning as well. For example, during swallowing, contraction of the genioglossus and palatoglossus can fix the dorsal tongue surface against the hard palate, and the hyoglossus can pull the hyoid upward. However, the surface of the tongue is considered to move freely during speech, and moves laterally or rotates with large amplitude during feeding. Thus, because of the various tongue surface motions involved in feeding and speech, the tongue was regarded as the dependent variable and the jaw and hyoid as the independent variables in our regression model.

Kinematic linkage during eating: vertical dimension

The high average β values of the jaw and hyoid in the vertical dimension during eating reflected a significant contribution of these structures in determining tongue position. However, the β of the jaw and hyoid in the model varied considerably for the ATM and PTM. These differences are likely due to the relative anatomical locations and muscle connections of the jaw and hyoid to the tongue body; jaw position was more associated with positioning of the anterior part of the tongue, while hyoid position was more related to posterior tongue positioning. The genioglossus and hyoglossus muscles are two extrinsic tongue muscles connecting the tongue to the mandible and hyoid bone. The genioglossus runs from the mental spine of the mandible into the midline of the tongue body, protruding from the tongue body. The hyoglossus runs from the superior border of the greater corn of the hyoid bone to the lateral side of the tongue to lower the dorsal surface of the tongue or raise the hyoid. The physical connection of these two muscles may produce stronger kinematic linkages from the jaw or hyoid to different parts of the tongue during feeding. Our findings indicate that vertical movement of the anterior part of the tongue is determined by vertical jaw movement during eating of food, while the posterior part of the tongue is more affected by vertical hyoid movement.

One shortcoming of this study was that the tongue moves laterally and rotates during feeding, but the two-dimensional videofluorographic observation ignored the lateral movements of the structures. However, the findings in previous studies suggest that lateral tongue motion or rotation has rhythmic coordination with masticatory jaw movement5, 6

Kinematic linkage during eating: horizontal dimension

In the horizontal dimension, the β of the hyoid was significantly high in the regression model during eating, but that of the jaw was barely significant. This finding indicates that in the horizontal dimension tongue movement is strongly influenced by hyoid movement and is more independent from jaw movement. The tongue and hyoid were seen to move horizontally with a large amplitude. The muscles of the tongue and hyoid are attached to the mandible and to the cranial bones, so the coordinated contractions of these muscles may produce synchronous antero-posterior movements of the tongue and hyoid during eating. On the other hand, the horizontal range of jaw movement is anatomically limited because of the structure of the temporo-mandibular joint, which produces a wide range of vertical jaw motion but small antero-posterior movement. This may account for the weak influence of horizontal jaw movement on antero-posterior tongue movement in feeding. However, the jaw can serve as a stable platform, from which rhythmic tongue muscles activities may act to produce rhythmic tongue movement in the horizontal dimension.

Kinematic linkage during speech

During eating of foods, the position of the hyoid was an important factor in determining tongue position, especially that of the PTM. During speech, however, the average β of the hyoid for both ATM and PTM was nearly zero. This suggests that hyoid position has little influence on tongue movement during speech in either dimension. Our group previously reported using the same dataset that jaw and tongue movements in speech occurred within the sagittal domains used for eating, but that the hyoid domains were significantly different between speaking and eating.19 We also found that the centroid position of the hyoid was more anterior and inferior and the variance of hyoid movement was smaller during speech. These findings were confirmed in the current study in that the role of the hyoid in eating and speech was indeed different and that tongue movement was more independent from hyoid movement during speech.

The main contributor to the kinematic linkage between the jaw and tongue is probably the mechanical connection of these structures. However, a substantial contribution of jaw movement to tongue movement in speech should be considered as well. Sanguineti et al. presented a biomechanical model of the tongue, jaw, hyoid, and larynx with their muscles based on x-ray recordings of midsagittal vocal tract motions 18, 24. They found that, without consideration of the dynamic interaction of the structures of the vocal tract, the model led to incorrect predictions of tongue movements; they concluded that the jaw was not simply a moving frame of reference for the tongue and that jaw motion had a substantial effect on the changes in shape and position of the tongue. Westbury et al. reported that tongue movement was decoupled from concurrent movements of the lower jaw during speech 12, 25. Taken together, the kinematic relationship between the jaw and tongue in speech derives not only from their mechanical connection, but also from the dynamic interactions of these structures.

Conclusion

This present study, using a multiple regression model, revealed that movements of the tongue surface had various correlations with jaw and hyoid motions during eating and speech. The anterior and posterior portions of the tongue were influenced differently by jaw and hyoid movements; in the vertical dimension, the movement of the anterior portion of the tongue was more correlated with jaw movement but the posterior portion of the tongue was more with hyoid movement. In the horizontal plane, tongue movement was significantly influenced by the hyoid, but not the jaw. During speech, tongue movements were less predictable from jaw and hyoid movements than during eating mainly due to the decreased influence of hyoid movement. Our findings indicate that future models of tongue surface motion during eating and speech should consider the significant impact of both jaw and hyoid movements.

Acknowledgments

The late Dr. Karen Hiiemae contributed immeasurably to this work. We could not have done this work without her support and instruction. We would also like to thank Chune Yang and Dr. Rebecca German for their extraordinary support and assistance. This research was supported by USPHS Award R01 DC02123 from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (JBP, KM), Health Sciences Research Grants (H12-choujyu-21 and H15-21EBM-018) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (KM), and a Research fellowship from the Medstar Research Institute (KM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tsuiki S, Ono T, Ishiwata Y, Kuroda T. Functional divergence of human genioglossus motor units with respiratory-related activity. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(5):906–910. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15e16.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiiemae KM, Palmer JB. Tongue movements in feeding and speech. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14(6):413–429. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone M, Lundberg A. Three-dimensional tongue surface shapes of English consonants and vowels. J Acoust Soc Am. 1996;99(6):3728–3737. doi: 10.1121/1.414969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardran GH, Kemp EH. A radiographic study of the movements of the tongue in swallowing. Dent Pract. 1955;5:252–263. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer JB, Hiiemae KM, Liu J. Tongue-jaw linkages in human feeding: a preliminary videofluorographic study. Arch Oral Biol. 1997;42(6):429–441. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mioche L, Hiiemae KM, Palmer JB. A postero-anterior videofluorographic study of the intra-oral management of food in man. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47(4):267–280. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(02)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertrich I, Ackermann H. Lip-jaw and tongue-jaw coordination during rate-controlled syllable repetitions. J Acoust Soc Am. 2000;107(4):2236–2247. doi: 10.1121/1.428504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goozee JV, Lapointe LL, Murdoch BE. Effects of speaking rate on EMA-derived lingual kinematics: a preliminary investigation. Clin Linguist Phon. 2003;17(4–5):375–381. doi: 10.1080/0269920031000079967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrd D, Lee S, Riggs D, Adams J. Interacting effects of syllable and phrase position on consonant articulation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2005;118(6):3860–3873. doi: 10.1121/1.2130950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartle CJ, Goozee JV, Scott D, Murdoch BE, Kuruvilla M. EMA assessment of tongue-jaw co-ordination during speech in dysarthria following traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2006;20(5):529–545. doi: 10.1080/02699050500487613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostry DJ, Munhall KG. Control of jaw orientation and position in mastication and speech. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71(4):1528–1545. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.4.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westbury JR, Lindstrom MJ, McClean MD. Tongues and lips without jaws: a comparison of methods for decoupling speech movements. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45(4):651–662. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/052). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franks HA, Crompton AW, German RZ. Mechanism of intraoral transport in macaques. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1984;65(3):275–282. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330650307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiiemae KH, Thexton A, McGarrick J, Crompton AW. The movement of the cat hyoid during feeding. Arch Oral Biol. 1981;26(2):65–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(81)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thexton A, McGarrick J, Hiiemae K, Crompton A. Hyo-mandibular relationships during feeding in the cat. Arch Oral Biol. 1982;27(10):793–801. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(82)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pancherz H, Winnberg A, Westesson PL. Masticatory muscle activity and hyoid bone behavior during cyclic jaw movements in man. A synchronized electromyographic and videofluorographic study. American journal of orthodontics. 1986;89(2):122–131. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(86)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westbury JR. Mandible and hyoid bone movements during speech. J Speech Hear Res. 1988;31(3):405–416. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3103.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanguineti V, Laboissiere R, Ostry DJ. A dynamic biomechanical model for neural control of speech production. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;103(3):1615–1627. doi: 10.1121/1.421296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiiemae KM, Palmer JB, Medicis SW, Hegener J, Scott Jackson B, Lieberman DE. Hyoid and tongue surface movements in speaking and eating. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47(1):11–27. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(01)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. 4. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClean MD, Tasko SM. Association of orofacial with laryngeal and respiratory motor output during speech. Exp Brain Res. 2002;146(4):481–489. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darley F, Aronson A, Brown J. Motor Speech Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velleman P. Definition and comparison of robust nonlinear data smoothing algorithms. J Am Stat Assoc. 1980;75:609–615. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanguineti V, Laboissiere R, Payan Y. A control model of human tongue movements in speech. Biological cybernetics. 1997;77(1):11–22. doi: 10.1007/s004220050362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westbury JR, Severson EJ, Lindstrom MJ. Kinematic event patterns in speech: special problems. Language and speech. 2000;43(Pt 4):403–428. doi: 10.1177/00238309000430040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]