Abstract

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis enables visualization of the subcellular locations of protein interactions in living cells. We investigated the temporal resolution and the quantitative accuracy of BiFC analysis using fragments of different fluorescent proteins. We determined the kinetics of BiFC complex formation in response to the rapamycin-inducible interaction between the FK506 binding protein (FKBP) and the FKBP-rapamycin binding domain (FRB). Fragments of YFP fused to FKBP and FRB produced detectable BiFC complex fluorescence 10 minutes after rapamycin addition and a ten-fold increase in the mean fluorescence intensity in 8 hours. The N-terminal fragment of the Venus fluorescent protein fused to FKBP produced constitutive BiFC complexes with several C-terminal fragments fused to FRB. A chimeric N-terminal fragment containing residues from Venus and YFP produced either constitutive or inducible BiFC complexes depending on the temperature at which the cells were cultured. The concentrations of inducers required for half-maximal induction of BiFC complex formation by all fluorescent protein fragments tested were consistent with the affinities of the inducers for unmodified FKBP and FRB. Treatment of the FK506 inhibitor of FKBP-FRB interaction prevented the formation of BiFC complexes by FKBP and FRB fusions, but did not disrupt existing BiFC complexes. Proteins synthesized prior to rapamycin addition formed BiFC complexes with the same efficiency as newly synthesized proteins. Inhibitors of protein synthesis attenuated BiFC complex formation independent of their effects on fusion protein synthesis. The kinetics at which they inhibited BiFC complex formation suggest that they prevented association of the fluorescent protein fragments, but not the slow maturation of BiFC complex fluorescence. Agents that induce the unfolded protein response also reduced formation of BiFC complexes. The effects of these agents were suppressed by cellular adaptation to protein folding stress. In summary, BiFC analysis enables detection of protein interactions within minutes after complex formation in living cells, but does not allow detection of complex dissociation. Conditional BiFC complex formation depends on the folding efficiencies of fluorescent protein fragments and can be affected by the cellular protein folding environment.

Keywords: Visualization of protein interactions, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry, protein folding, FKBP-FRB association

Introduction

Protein interactions are a central mechanism for the integration of cellular signals and for the generation of regulatory specificity. Several methods have been developed for the visualization of protein complexes in living cells 1; 2; 3. The sensitivity, the signal to background ratio and the spatial and temporal resolutions of the assay are important criteria to use when deciding among alternative methods for imaging protein interactions.

The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay enables direct visualization of protein interactions in living cells 1; 4. This assay is based on the association of two non-fluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein when they are brought in proximity to each other by an interaction between two proteins fused to the fragments. This association results in the formation of a fluorescent complex at the site of the interaction. The BiFC assay has been used to visualize hundreds of protein interactions, and allows determination of the subcellular localization of protein complexes at high spatial resolution (sitemaker.umich.edu/kerppola.bifc) 1.

Many different fluorescent protein fragments have been identified that can be used in BiFC assays 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10. The variety of fragments that can be used provides many benefits, including the ability to visualize multiple protein interactions in the same cell 5. Simultaneous imaging of multiple protein interactions enables direct comparison of their distributions as well as analysis of the competition for common interaction partners 11. Different fluorescent protein fragments also affect the fluorescence intensity of BiFC complexes formed by cognate interaction partners as well as the fluorescence intensity produced by spontaneous association of the fluorescent protein fragments independent of an interaction between proteins fused to the fragments 7; 9. The magnitudes and kinetics of the changes in fluorescence intensity in response to inducible protein interactions have not been compared between BiFC assays using different fluorescent protein fragments. It has also not been established if the intensity of BiFC complex fluorescence quantitatively corresponds to interactions between the corresponding proteins that are not fused to fluorescent protein fragments.

BiFC complex formation is related to protein folding since the two fluorescent protein fragments must fold upon association to form a fluorescent complex 4. Amino acid substitutions as well as changes in the cellular environment that affect folding of the fluorescent protein fragments could therefore affect BiFC complex formation. The fluorescent protein fragments tend to aggregate in vitro in the absence of their complementary partners. The relationship between protein folding and BiFC complex formation has not been examined in living cells. It has also not been established if BiFC complex formation requires newly synthesized proteins or if un-associated fusion proteins remain competent to form BiFC complexes in living cells.

The fluorophore of green fluorescent proteins is produced by cyclization, dehydration and oxidation of a tri-peptide at the center of the protein 12. These autocatalytic reactions require prior folding of the fluorescent protein, presumably because they require the unique environment provided by the β barrel structure surrounding the reactive residues 13. The rates of the multiple steps in fluorophore formation vary for different fluorescent proteins, corresponding to overall half-times of about an hour for YFP and about 10 minutes for Venus in vitro 14. In vitro studies of the rates of BiFC complex formation and dissociation have produced divergent results 4; 15; 16; 17. Whereas BiFC complexes formed by YFP fragments fused to proteins become fluorescent with a half-time of approximately 60 minutes 4, BiFC complexes formed by GFP fragments chemically linked to oligonucleotides become fluorescent within seconds after mixing 17. Some BiFC complexes have been detected within minutes after stimulating cells, but the possibility that these represent pre-existing BiFC complexes whose fluorescence is enhanced by changes in cellular conditions has not been excluded 18. Thus, the rate of BiFC complex formation in living cells is not known.

Association of the fluorescent protein fragments to form the BiFC complex produces four new interaction interfaces in the β barrel. Each of these interfaces contains between 6 and 9 hydrogen bonds. These hydrogen bonding networks are very stable since the protons mediating the hydrogen bonds have binding energies of 6–11 kcal mol−1 based on deuterium exchange studies of intact fluorescent proteins 19. Since neither of the fluorescent protein fragments forms a contiguous β-sheet in the intact fluorescent protein, it is likely that the separate fragments are at least partially unfolded. No dissociation of BiFC complexes formed by YFP or GFP fragments fused to leucine zipper interaction partners is detected under non-denaturing conditions in vitro 4; 16. However, BiFC complexes formed by 200 nM GFP fragments chemically linked to oligonucleotides are disrupted by incubation with 100-fold excess of competitor oligonucleotide or 2 mM Mg2+ 17. BiFC complexes formed by YFP fragments fused to phospholipase Cβ dimers are also disrupted by addition of competitor to membrane preparations and by acetylcholine treatment of living cells 15. Treatment of cells that contain other BiFC complexes with agents predicted to inhibit protein interactions can also reduce fluorescence intensity 18. The possibility that these changes are caused by degradation or re-localization of the complexes has not been excluded. Thus, the effects of fluorescent protein fragment association on BiFC complex stability in living cells remain unclear.

The dynamics of BiFC complexes have significant implications both for the temporal resolution and the specificity of the BiFC assay. If association of the fluorescent protein fragments stabilizes BiFC complexes, then the specificity of the BiFC assay depends on the kinetics of fragment association. We here establish the kinetics of BiFC complex formation by different fluorescent protein fragments and the magnitudes of the increases in fluorescence in response to a ligand-inducible protein interaction. We also compare the effects of different ligand concentrations on BiFC complex formation to determine if the fluorescence intensity reflects the proportion of the interaction partners that associate with each other when they are not fused to the fluorescent protein fragments. We examine the reversibility of BiFC complex formation using competitive inhibitors of ligand binding. Finally, we investigate the effects of inhibitors of translation and protein folding on BiFC complex formation to elucidate the effects of disturbances in the biosynthesis of native proteins on fluorescent protein fragment association.

RESULTS

To determine the kinetics of BiFC complex formation and to compare the characteristics of different fluorescent protein fragments, we visualized a ligand-inducible protein interaction using BiFC analysis. This strategy enables determination of the fluorescence intensities of the same cells in the absence of ligand and at different times after ligand addition. It also enables comparison of the ligand concentration-dependence of BiFC complex formation with the ligand binding affinities of the interaction partners lacking the fluorescent protein fragment fusions. Finally, it enables examination of the effects of changes in the cellular environment before or after ligand addition on BiFC complex formation.

We used rapamycin-inducible complex formation by FKBP (the FK506-binding protein) and FRB (the FKBP and rapamycin binding domain of the target of rapamycin protein) as a model interaction 20; 21; 22. This interaction has been characterized in detail and it has been used to control interactions between other proteins by fusing them to FKBP and FRB 23; 24; 25; 26; 27. No interaction between FKBP and FRB in the absence of rapamycin has been detected 28, but the possibility of weak or transient ligand-independent interactions cannot be excluded.

Rapid detection of protein interactions using the BiFC assay

To investigate the kinetics of fluorescent BiFC complex formation, we determined the time-course of fluorescence complementation in response to rapamycin-inducible FKBP-FRB interaction. We expressed complementary fragments of YFP (YN and YC) fused to the C-terminal ends of FKBP and FRB in COS-1 cells. The cells were treated with rapamycin, fixed at different times after treatment, and imaged by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1A, images). Prior to rapamycin treatment, the low signal was not significantly different from the scatter produced by non-transfected cells (data not shown). Ten minutes after the addition of a saturating concentration of rapamycin, higher fluorescence intensities were detected in 2% of the cells by microscopy.

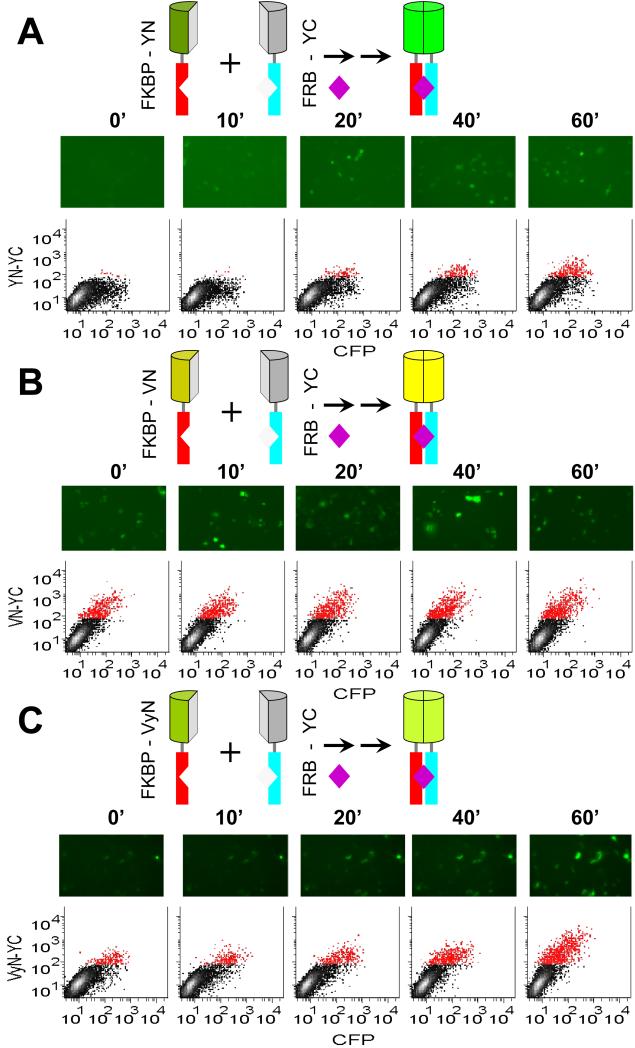

Figure 1. Time-course of fluorescence complementation upon FKBP-FRB interaction.

(A) Rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-YN and FRB-YC. The diagrams above the images represent the fusion proteins expressed in the cells and the complex formed upon rapamycin (purple diamond) addition. The N-termini of the fusion proteins point down in these diagrams. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC together with a CFP normalization control were cultured at 37 °C, treated with 100 nM rapamycin at time 0 and fixed at the times indicated. The cells were imaged by microscopy and their fluorescence intensities were measured using flow cytometry. Each image shows a field with approximately 100 cells, only some of which are fluorescent because the fusion proteins were transiently expressed in only a subpopulation of the cells. Each scatterplot shows the fluorescence intensities of 10,000 cells with CFP fluorescence shown on the horizontal axis and BiFC fluorescence on the vertical axis. Cells that had BiFC intensities higher than the background signal of more than 99% of non-transfected cells were plotted in red color. (B) Rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VN and FRB-YC. Cells were treated and analyzed as described in part (A) except that FKBP-VN was used instead of FKBP-YN. (C) Rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP- VyN and FRB-YC. Cells were treated and analyzed as described in part (A) except that FKBP-VyN was used instead of FKBP-YN and the cells were imaged live.

To quantify rapamycin-inducible changes in BiFC fluorescence over time, we measured the fluorescence intensities of individual cells by flow cytometry at different times after rapamycin addition (Fig. 1A, graphs). In the absence of rapamycin, the fluorescence intensities of cells that expressed FKBP and FRB fused to the YFP fragments were not significantly different from the low background signal of non-transfected cells (data not shown). To normalize for differences in the levels of protein expression in individual cells caused by variations in transfection efficiency, we co-transfected a plasmid expressing a cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fusion and calculated the ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence (Fig. 2A). Twenty minutes after rapamycin addition, the mean fluorescence intensity of the transfected cells measured by flow cytometry was significantly higher than the background signal of unstimulated cells (paired t-test p<0.05). In some experiments a lag phase of about 10 minutes was observed, but the mean fluorescence intensities from multiple independent experiments did not show a lag phase. The fluorescence increased for at least 8 hours and reached a level about 10-fold above the background observed in the absence of rapamycin. This represents a minimum estimate of the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by YFP fragments fused to FKBP and FRB since the background in the absence of inducer is primarily due to light scatter. There was no significant change in the levels of fusion protein expression over this time in the presence or absence of rapamycin (Fig. S1A, S1B). The protracted increase in BiFC complex formation therefore did not result from an increase in the concentrations of fusion proteins in each cell.

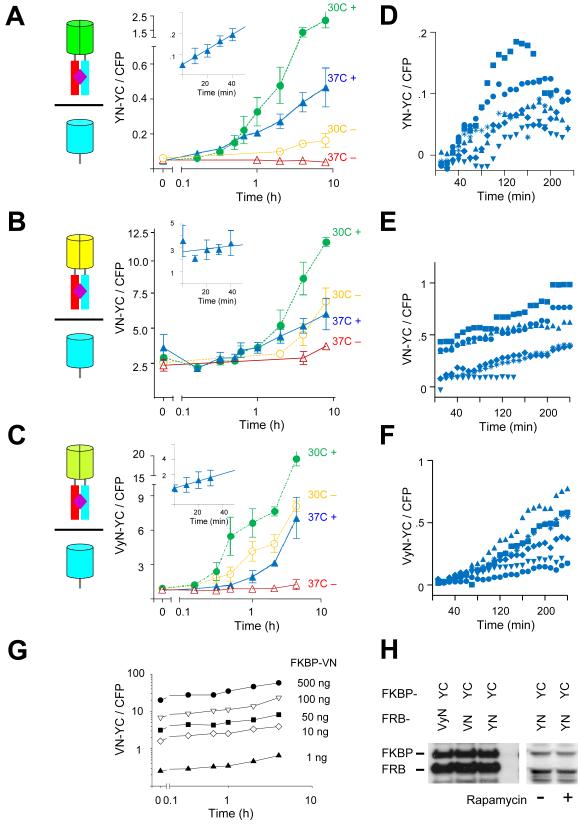

Figure 2. Quantitative analysis of the kinetics and inducibility of BiFC complex formation by different fluorescent protein fragments fused to FKBP and FRB in cell populations and individual cells.

(A) Time-course of fluorescence complementation following rapamycin treatment of cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC. The diagrams represent the BiFC complexes formed in the cells as shown in Figure 1. The graph shows the mean ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence measured by flow cytometry plotted as a function of time after the addition of 100 nM rapamycin (filled symbols). Cells cultured in the absence of rapamycin were analyzed in parallel (open symbols). The cells were incubated at 37°C prior to stimulation, kept at 37°C (triangles) or shifted to 30°C (circles) at time 0. The data represent means and standard deviations of three to five independent experiments. Note that the time axis is logarithmic. The inset shows the data at early times after stimulation on a linear scale. (B) Time-course of fluorescence complementation following rapamycin treatment of cells that expressed FKBP-VN and FRB-YC plotted as described in part A. The data represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments. (C) Time-course of fluorescence complementation following rapamycin treatment of cells that expressed FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC plotted as described in part A. The data represent means and standard deviations of three independent experiments. (D) Time-course of fluorescence complementation in individual cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC cultured at 37 °C following the addition of 100 nM rapamycin at time 0. The cells were imaged by microscopy at 10 minute intervals. Cells were cultured in CO2 independent medium. The fluorescence intensities of individual cells were quantified and plotted using different symbols. (E) Time-course of fluorescence complementation in individual cells that expressed FKBP-VN and FRB-YC imaged by microscopy as described in part D. (F) Time-course of fluorescence complementation in individual cells that expressed FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC imaged by microscopy as described in part D. (G) Effects of the amount of plasmid encoding FKBP-VN transfected on constitutive and inducible BiFC complex formation with FRB-YC. The indicated amounts of the FKBP-VN plasmid were transfected with 500 ng FRB-YC plasmid and the cells were treated with 100 nM rapamycin at time 0. The cells were fixed at the times indicated and analyzed by flow cytometry. The graph shows the mean ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence as a function of the time after rapamycin treatment. (H) Comparison of the expression levels of FKBP and FRB fused to the fluorescent protein fragments indicated above the lanes. Extracts of cells transfected with plasmids encoding the combinations of fusion proteins indicated above the lanes were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-GFP antibody. The cells either treated with rapamycin (+) or untreated (−) as indicated below the lanes.

BiFC complex formation is often imaged at 30 °C because of the higher fluorescence intensity that is generally observed under these conditions. Incubation of cells expressing FKBP and FRB fusions at 30 °C during rapamycin treatment resulted in a larger increase in fluorescence intensity than that observed in cells incubated at 37 °C (Fig. 2A). However, the fluorescence intensities of cells grown in the absence of rapamycin also increased under these conditions. The ratio between rapamycin-inducible BiFC fluorescence and constitutive signal in the absence of rapamycin for cells incubated at 30 °C was lower than for cells incubated at 37 °C. These results indicate that the common practice of performing BiFC analysis at 30 °C does not enhance detection of the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP and FRB fusions. Rapamycin had no effect on the fluorescence intensities of cells that expressed intact fluorescent proteins or fluorescent protein fragments fused to proteins other than FKBP and FRB (Fig. S1C). BiFC analysis therefore enabled rapid and quantitative detection of inducible protein interactions in individual cells and cell populations.

Effects of different fluorescent protein fragments on detection of inducible protein interactions using BiFC analysis

We set out to determine if BiFC assays based on fusions to different fluorescent protein fragments differ in their sensitivities or kinetics of fluorescent complex formation. Fragments of many different fluorescent proteins have been used in BiFC analysis 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10. Fragments of the Venus fluorescent protein have gained widespread use due to the higher fluorescence intensity and faster folding of intact Venus compared to YFP 14. Studies of BiFC complexes formed by different combinations of N- and C-terminal fragments of YFP, Venus and CFP have shown that the N-terminal fragments have a greater effect on the fluorescence intensity and spectrum of the BiFC complex 5; 7 (C. Vincenz and T. K. Kerppola, unpublished results). We therefore focused on effects of different N-terminal fragments on constitutive and rapamycin-inducible BiFC complex formation.

Cells that expressed the N-terminal fragment of Venus fused to FKBP (FKBP-VN) together with FRB-YC had high constitutive fluorescence intensities in the absence of rapamycin (Fig. 1B). The mean fluorescence intensity of the cells increased approximately 3-fold following rapamycin treatment (Fig. 2B). The fluorescence intensity of untreated cells that expressed FKBP-VN and FRB-YC also increased over time. Because of constitutive BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VN and FRB-YC, the increase in fluorescence intensity in response to rapamycin treatment was not statistically significant (paired t-test p<0.05) until 4 hours after rapamycin addition. The efficient association of the N-terminal fragment of Venus fused to FKBP with FRB-YC compromised BiFC analysis of rapamycin-inducible FKBP-FRB interaction.

The N-terminal fragments of Venus and YFP differ by three amino acid residues. Each of these residues contributes to the difference in the spontaneous association of the Venus and YFP fragments alone in Xenopus embryos 9. We examined BiFC complex formation by a chimera containing the L46 and L64 residues from Venus and M153 from YFP fused to FKBP (FKBP-VyN) together with FRB-YC (see Movie 1 for locations of amino acid substitutions in the YFP structure). Cells that expressed FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC cultured at 37 °C had intermediate constitutive fluorescence intensities in the absence of rapamycin relative to cells that expressed FKBP-YN or FKBP-VN together with FRB-YC (Fig. 1C). In cells cultured at 37 °C, the fluorescence intensity increased about 10-fold in response to rapamycin treatment (Fig. 2C). Cells shifted to 30 °C also exhibited a time-dependent increase in fluorescence, but this increase was mostly independent of rapamycin treatment. FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC therefore form BiFC complexes constitutively under these conditions. The increase in fluorescence of cells that expressed FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC cultured at 37 °C was statistically significant (paired t-test p<0.05) 20 minutes after rapamycin treatment. The effects of temperature on the constitutive versus inducible association of the N-terminal VyN chimera fused to FKBP with FRB-YC suggests that folding of the fluorescent protein fragments affects BiFC complex formation.

We examined the kinetics of BiFC complex formation in individual cells to determine if the mean rate of BiFC complex formation in each population reflected the kinetics of BiFC complex formation in individual cells. To examine the time-dependent changes in fluorescence intensities of individual cells, we monitored the fluorescence intensities of live cells by microscopy (Movies 2-4). The kinetics and magnitudes of the changes in fluorescence of individual cells were similar to those observed in the cell population for each combination of fluorescent protein fragments tested (compare Fig. 2D-F with Fig. 2A-C). The absolute fluorescence intensities of individual cells varied over a wide range, presumably because of differences in the levels of fusion protein expression. The kinetics of BiFC complex formation in individual cells were generally proportional to the fluorescence intensities of the cells in each population, suggesting that the rates of BiFC complex formation were proportional to the levels of fusion protein expression. The fluorescence intensities of cells that expressed YN or VyN fused to FKBP together with FRB-YC increased approximately 10-fold, whereas the fluorescence intensities of cells that expressed the VN fused to FKBP together with FRB-YC increased 2–3 fold, consistent with the differences that were observed in the mean fluorescence intensities of these cell populations.

To examine if the concentrations of the fusion proteins expressed in the cell affected either the rate or the inducibility of BiFC complex formation, we varied the amounts of the plasmids transfected into cells. The rate of increase in BiFC complex fluorescence produced by FKBP-VN and FRB-YC varied nearly in proportion to plasmid concentration (Fig. 2G, note exponential scales). The mean fluorescence intensities of the cells were approximately proportional to the plasmid concentrations, suggesting that the levels of protein expression were proportional to the amounts of plasmids transfected. The rate of BiFC complex formation was therefore proportional to the concentrations of the fusion proteins over a 500-fold range of protein concentrations.

Both constitutive and inducible BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VN as well as FKBP-VyN with FRB-YC increased in proportion to plasmid concentration (Fig. S2D). Thus, the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VN as well as by FKBP-VyN with FRB-YC was largely unaffected by plasmid concentration. It was not possible to determine the effect of plasmid concentration on the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-YN and FRB-YC since constitutive BiFC complex formation could not be detected above the background signal caused by light scatter. Taken together, these results suggest that the rate-limiting step(s) in the pathway for BiFC complex formation did not change over the 500-fold range of plasmid concentrations tested.

Western blot analysis demonstrated that FKBP fusions to YN, VN and VyN were expressed at similar levels (Fig. 2H). Incubation of cells at 37 °C versus 30 °C for up to 8 hours in the absence or presence of rapamycin had no detectable effect on the level of fusion protein expression (Fig. S1A, S1B). The differences in rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by YN, VN and VyN fusions under different conditions were therefore not due to differences in their expression levels.

Multicolor BiFC analysis of regulated protein interactions

The use of BiFC complexes with distinct spectra enables simultaneous visualization of multiple protein interactions in the same cell and analysis of the competition for common interaction partners by different proteins 5; 11. To determine if detection of multiple inducible complexes in the same cell would be possible, we first examined if fragments of fluorescent proteins that produce complexes with spectra distinct from YFP fragments could be used to detect inducible protein interactions. FKBP and FRB fusions to CFP fragments (FKBP-CN and FRB-CC) exhibited rapamycin-inducible BiFC complex formation similar to that observed by fusions to YFP fragments (Fig. S2A). FRB fused to the C-terminal fragment of CFP (FRB-CC) in combination with FKBP fused to the N-terminal fragment of YFP (FKBP-YN) produced low constitutive signal and high inducibility. In contrast, the same FRB-CC fusion in combination with FKBP fused to the N-terminal fragment of Venus (FKBP-VN), produced high constitutive signal and low inducibility (Fig. S2B, S2C). Thus, the N-terminal fragments of YFP and Venus differ in the relative efficiencies of constitutive and inducible BiFC complex formation when analyzed in combination with different C-terminal fluorescent protein fragments.

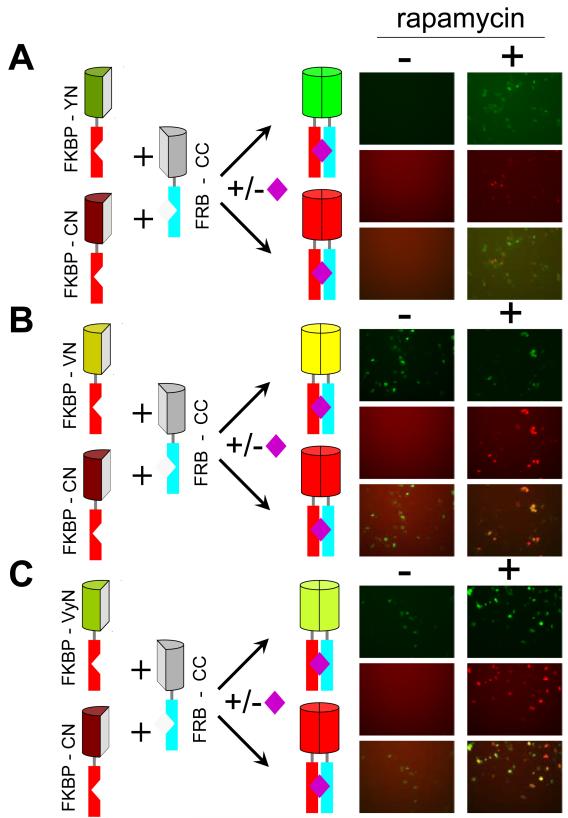

To determine if the differences in constitutive and inducible BiFC complex formation by different fluorescent protein fragments were observed when they were expressed in the same cell, we co-expressed FKBP-YN, -VN and -VyN individually with FKBP-CN and FRB-CC. BiFC complexes formed by FKBP-YN, -VN or -VyN with FRB-CC have spectra that can be distinguished from those formed by FKBP-CN and FRB-CC (Fig. 3). In cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FKB-CN with FRB-CC, there was little constitutive signal and high inducibility of both BiFC complexes (Fig. 3A). In contrast, in cells that expressed FKBP-VyN or FKBP-VN with FKBP-CN and FRB-CC, there was higher constitutive BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VyN or FKBP-VN with FRB-CC, but low constitutive BiFC complex formation by FKBP-CN with FRB-CC in the same cells (Fig. 3B and C). Thus, differences in the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by different fluorescent protein fragments are intrinsic to the individual fusions and do not reflect differential cellular responses to fusion protein expression. These results also demonstrate that multiple regulated protein interactions can be imaged simultaneously in the same cell.

Figure 3. Comparison of the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by different combinations of fluorescent protein fragments fused to FKBP and FRB in the same cells using multicolor BiFC analysis.

(A) Rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-YN and FKBP-CN with FRB-CC in the same cells. The diagrams on the left indicate the fusion proteins expressed in the cells and the alternate complexes that can be formed by different combinations of the fusions. The left column of images shows fields of cells cultured at 37 °C in the absence of rapamycin and the right column of images shows fields of cells cultured in the presence of 100 nM rapamycin for 4 hours. The upper pair of panes (green) shows YN-CC BiFC complexes, the middle pair of panes (red) shows CN-CC complexes and the lower pair of panes shows an overlay of the upper and middle panes. (B) Rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VN and FKBP-CN with FRB-CC in the same cells. The cells were treated and imaged as described in part A, except FKBP-VN was used in place of FKBP-YN. (C) Rapamycin inducibility of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VyN and FKBP-CN with FRB-CC in the same cells. The cells were treated and imaged as described in part A, except that FKBP-VyN was used in place of FKBP-YN.

Effects of different fluorescent protein fragment fusions on BiFC complex formation by cognate versus non-cognate partners

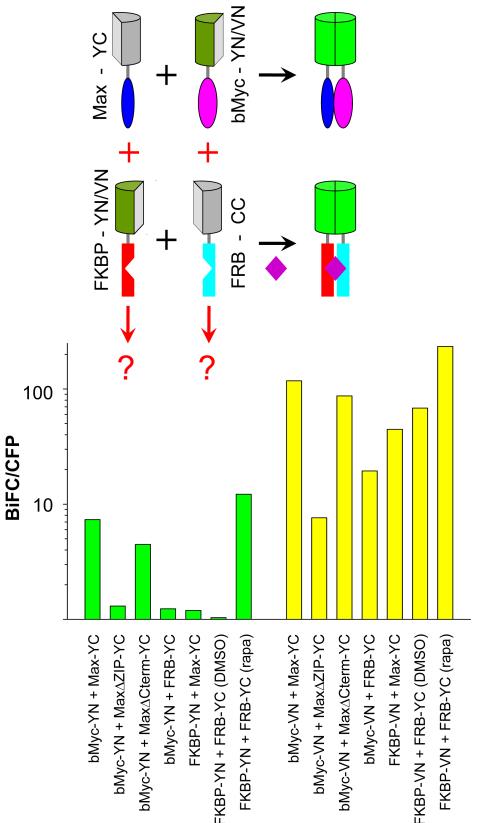

To examine the effects of different fluorescent protein fragments on BiFC complex formation by proteins other than FKBP and FRB, we compared BiFC complex formation by YN versus VN fused to the bHLH-ZIP domain of Myc (bMyc-YN vs. bMyc-VN) with Max-YC. bMyc-VN produced about an order of magnitude higher fluorescence intensity than bMyc-YN in combination with Max-YC (Fig. 4). Deletion of the leucine zipper of Max reduced the fluorescence intensities of BiFC complexes formed by both bMyc-VN and bMyc -YN with MaxΔZIP-YC by about an order of magnitude. A deletion of similar size in the C-terminal region of Max (MaxΔCterm) had little effect on BiFC complex formation by either combination of fusions, demonstrating that the changes in BiFC complex formation caused by deletion of the leucine zipper were due to altered dimerization. Deletion of the leucine zipper therefore had similar effects on BiFC complex formation by the N-terminal fragments of YFP and Venus fused to bMyc with Max-YC.

Figure 4. BiFC complex formation by YN versus VN fused to cognate and non-cognate interaction partners.

Comparison of BiFC complex formation by YN and VN fused to wild type and mutated bHLHZIP proteins and to FKBP and FRB. The diagrams above the histogram show the cognate (black) and non-cognate (red) interactions. The green bars show the fluorescence intensities of BiFC complexes formed by YN fusions and the yellow bars the fluorescence intensities of the corresponding BiFC complexes formed by VN fusions. The plasmids indicated below each bar were co-transfected into COS-1 cells together with a plasmid expressing a CFP fusion used for normalization. Cells were fixed 20 hours post-transfection and their fluorescence intensities were measured by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the mean ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence for each combination of fusion proteins on a logarithmic scale.

We also examined BiFC complex formation by presumably non-specific association of Myc and Max with FRB and FKBP when the proteins were fused to YN and YC or VN and YC fragments. Cells that expressed these non-cognate partners fused to YN and YC had fluorescence intensities about an order of magnitude lower than those of cells that expressed the cognate interaction partners. However, the non-cognate partners fused to VN and YC produced fluorescence intensities that were 2–5 fold lower than those produced by normal interaction partners. The relative fluorescence intensities of BiFC complexes formed by different fluorescent protein fragments fused to cognate versus non-cognate interaction partners therefore varied depending on the fusion proteins investigated.

Effects of inducer concentration on BiFC complex formation

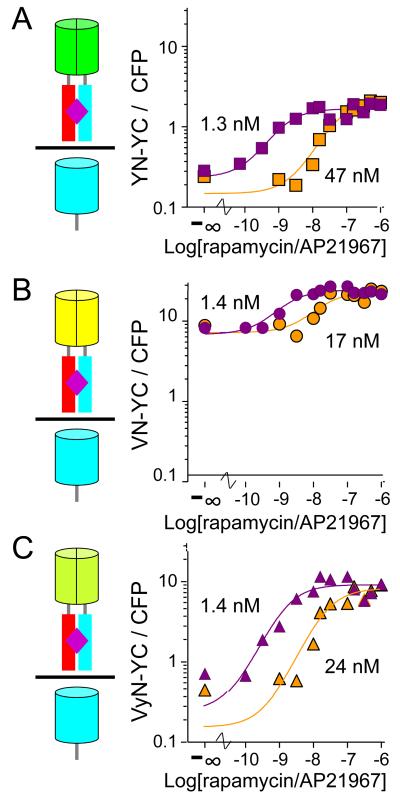

To determine if the intensity of BiFC complex fluorescence reflects the proportion of the interaction partners that interact with each other when they are not fused to fluorescent protein fragments, we investigated the effects of rapamycin and AP21967 (a rapamycin analog with lower binding affinity) concentrations on BiFC complex formation by YN, VN and VyN fused to FKBP and FRB-YC. The interaction between FKBP and FRB depends on inducer concentration and the affinity of the inducer for FKBP-FRB complexes 28; 29. All of the fluorescent protein fragment fusions had half-maximal efficiencies of BiFC complex formation at the same concentration of rapamycin (Fig. 5). Likewise, BiFC complex formation by all fusion proteins required about an order of magnitude higher AP21967 concentrations. This difference is consistent with the higher affinity of rapamycin binding to the FKBP-FRB complex and the difference between the effective concentrations of rapamycin and AP21967 in other cellular assays 28; 29. These results suggest that the increase in BiFC complex fluorescence in the presence of different inducer concentrations was proportional to the change in complex formation by FKBP and FRB lacking fluorescent protein fragment fusions.

Figure 5. Effects of inducer concentrations on BiFC complex formation.

Cells that expressed (A) FKBP-YN and FRB-YC (B) FKBP-VN and FRB-YC or (C) FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC were treated different concentrations of rapamycin (purple) or AP21967 (orange) for 4 hours at 37 °C. The cells were fixed and their fluorescence intensities were measured by flow cytometry. The mean ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence was plotted as a function of inducer concentration. The data shown are representative of 3–6 independent experiments for each inducer and combination of fusion proteins.

Effects of FK506 treatment on BiFC complex formation and stability

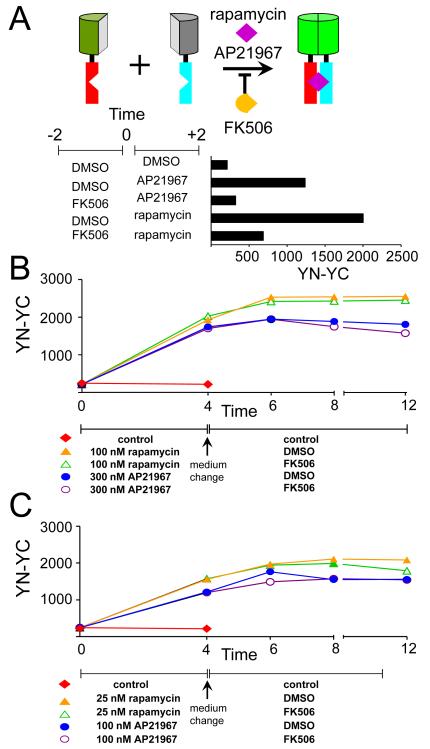

The difference in constitutive versus inducible BiFC complex formation by the YN, VN and VyN fusions could be due to differences in the stabilities of BiFC complexes formed by these fragments. To examine the stabilities of BiFC complexes in cells, we determined the effects of FK506 treatment, which can disrupt FKBP-FRB complexes under some conditions 30; 31. Pre-treatment of cells with FK506 blunted rapamycin and AP21967 induction of BiFC complex formation by FKBP-YN and FRB-YC (Fig. 6A). However, treatment of cells with FK506 after BiFC complex formation had little or no effect on their fluorescence intensities (Fig. 6B and 6C). BiFC complexes formed by all fluorescent protein fragments tested were stable for several hours in cells cultured in the presence of FK506 (Fig. S3). There was no detectable effect of FK506 pre-treatment on constitutive BiFC complex formation by FKBP-VN and FRB-YC (data not shown). Thus, FK506 treatment abrogated formation of new inducible BiFC complexes by FKBP and FRB fusions, but had little or no effect on pre-existing or constitutive BiFC complexes.

Figure 6. Effects of FK506 treatment on FKBP-FRB BiFC complexes.

(A) Effects of FK506 pre-treatment on rapamycin- and AP21967-inducible BiFC complex formation. The diagrams above the histogram indicate the proteins expressed in the cells. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC were treated with 1 μM FK506 or DMSO for 2 hours. The cells were transferred into medium that contained 100 nM rapamycin or 300 nM AP21967, incubated for 2 hours, fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry. The mean BiFC fluorescence intensities were plotted as a histogram. (B) Effects of FK506 treatment on BiFC complexes formed by FKBP-YN and FRB-YC. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC were incubated with 100 nM rapamycin (triangles), 300 nM AP21967 (circles) or control medium (diamonds) for 4 hours. The cells were washed (1X with PBS and 2X with complete medium) and transferred into medium containing 1 μM FK506 (open symbols) or DMSO vehicle (solid symbols). At the times indicated, the cells were fixed and their fluorescence intensities were measured by flow cytometry. The BiFC fluorescence intensities were plotted as a function of the time after inducer addition. The data are representative of two independent experiments. (C) Effects of FK506 treatment on BiFC complexes formed by FKBP-YN and FRB-YC at lower inducer concentrations. The cells were treated and analyzed as described in part B except that 25 nM rapamycin (triangles) or 100 nM AP21967 (circles) was used to induce complex formation.

Relationship between protein synthesis and BiFC complex formation

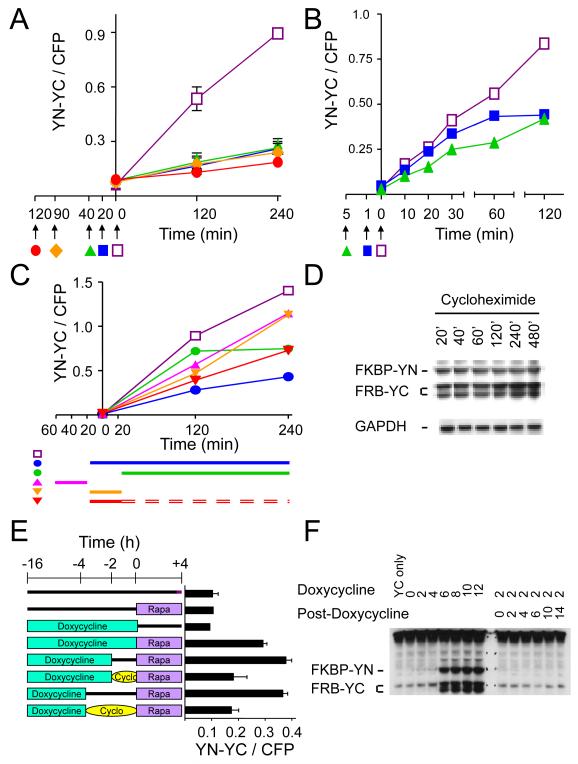

The protracted increase in BiFC complex fluorescence following rapamycin addition in the absence of a detectable change in fusion protein levels suggested that BiFC complex formation was either slow or required newly synthesized fusion proteins. In vitro studies of BiFC complex formation have shown that many fusion proteins aggregate in the absence of complementary interaction partners, providing a potential rational for a requirement for newly synthesized proteins 18. To examine this possibility, we used several independent approaches to determine if BiFC complex formation in cells required newly synthesized fusion proteins or if the fusion proteins remained competent to form BiFC complexes after synthesis. First, we added inhibitors of protein synthesis to the cells before treating them with rapamycin to induce FKBP-FRB association. Second, we controlled the timing of fusion protein synthesis by using a regulated expression vector. Finally, we tested if inhibitors of protein synthesis affected BiFC complex formation when they were added after protein synthesis was repressed.

We added cycloheximide to cells that expressed FKBP-YC and FRB-YC at different times before rapamycin treatment. Cycloheximide treatment attenuated BiFC complex formation much faster than it affected the steady-state levels of the fusion proteins (Fig. 7A, 7D). Cycloheximide added more than 20 minutes prior to rapamycin treatment reduced inducible BiFC complex formation by 50–80%. There was no detectable decrease in the levels of the fusion proteins during up to 8 hour incubation in the presence of cycloheximide, suggesting that fusion protein turnover was slow. Since the levels of the fusion proteins did not markedly increase in the time-frame of these experiments (Figs. S1A, S1B), these results also indicate that newly synthesized fusion proteins represented a small proportion of the total population of fusion proteins.

Figure 7. Effects of the time of fusion protein synthesis and cycloheximide treatment on BiFC complex formation.

(A) Attenuation of BiFC complex formation by cycloheximide added before rapamycin induction. Cell that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC were incubated in the presence (solid symbols) or absence (open symbols) of 50 μg/ml cycloheximide added at the times indicated by the arrows. 100 nM rapamycin was added of at time 0. The cells were fixed at the times indicated, analyzed by flow cytometry and the ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence was plotted as a function of time after rapamycin addition. (B) Rates of onset of cycloheximide inhibition of BiFC complex formation. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC were incubated in the presence (solid symbols) or absence (open symbols) of cycloheximide added at the times indicated by the arrows. 100 nM rapamycin was added of at time 0. The cells were fixed at the indicated times, analyzed by flow cytometry, and the ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence intensities was plotted as a function of time after rapamycin addition. (C) Recovery of BiFC complex formation after removal of cycloheximide. The cells were incubated in the presence of cycloheximide during the times indicated by the bars (▬) next to the symbols below the graph. Rapamycin was added at time 0 to the samples indicated by solid symbols. Rapamycin was replenished when cycloheximide was removed with the exception for the last sample, which was incubated in medium without rapamycin or cycloheximide for the time indicated by double dashed lines (=). The cells were fixed at the times indicated, analyzed by flow cytometry, and the mean ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence were plotted as a function of time after rapamycin addition. (D) Rates of FKBP-YN and FRB-YC turnover in the presence of cycloheximide. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN and FRB-YC were incubated in the presence of 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for the times indicated above the lanes and cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-GFP and anti-GAPDH antibodies. (E) Effects of the time of FKBP-YN and FRB-YC synthesis on BiFC complex formation. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter together with FRB-YC were incubated with 1 ug/ml doxycycline (teal box) or in control medium (line) for the times indicated. The cells were washed (1X PBS and 2X with complete medium) and incubated in medium without doxycycline in the presence (oval) or absence (line) of 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for either 2 or 4 hours as indicated. The cells were washed and incubated for an additional 4 hours in the presence (purple box) or absence (line) of 100 nM rapamycin. The cells were fixed and their fluorescence intensities were measured by flow cytometry. The mean ratios of BiFC to CFP fluorescence were plotted as a histogram. (F) Effects of doxycycline addition and removal on fusion protein synthesis. Cells that expressed FKBP-YN under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter together with FRB-YC were incubated with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for the time indicated above the lanes (top row). For the lanes on the right, the cells were washed and cultured in the absence of doxycycline for the times indicated. Cell extracts were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-GFP antibodies.

When cycloheximide was added immediately (1 minute) before rapamycin, the rate of fluorescent BiFC complex formation was nearly unaffected during the initial 30 minutes after induction (Fig. 7B). In contrast, a 5 minute pre-incubation with cycloheximide reduced the initial rate of rapamycin-inducible BiFC complex formation. Thus, cycloheximide had to be present for some time prior to rapamycin addition to inhibit the initial rate of BiFC complex formation. Taken together, these results suggest that cycloheximide inhibited fluorescent protein fragment association, but had little effect on the maturation of BiFC complexes formed prior to cycloheximide addition.

We examined if cycloheximide treatment affected BiFC complex formation following its removal and resumption of protein synthesis. The cells were washed thoroughly to remove cycloheximide and rapamycin was replenished as indicated after removal of the cycloheximide. Cycloheximide treatment reduced BiFC complex formation even when it was removed before rapamycin addition (Fig. 7C). Other structurally and mechanistically unrelated inhibitors of protein synthesis also attenuated BiFC complex formation (Fig. S4). The protracted effects of protein synthesis inhibitors on BiFC complex formation suggest that these inhibitors attenuated BiFC complex formation through mechanisms unrelated to the inhibition of fusion protein synthesis.

As an independent approach to test if fusion proteins synthesized prior to rapamycin addition were competent for BiFC complex formation, we expressed FKBP-YN using a doxycycline-inducible promoter and measured BiFC complex formation following rapamycin treatment at various times after the removal of doxycycline. Rapamycin treatment induced the same level of BiFC complexes whether it was added 0, 2 or 4 hours after doxycycline removal (Fig. 7E). There was no detectable induction of BiFC complexes in cells cultured in the absence of doxycycline (Fig. 7E), and no FKBP-YN synthesis was detectable by immunoblotting following doxycycline removal (Fig. 7F, right half). FKBP-YN synthesis was therefore strictly dependent on the presence of doxycycline. Thus, FKBP-YN fusions synthesized more than 4 hours before rapamycin addition formed BiFC complexes with an efficiency similar to proteins synthesized up until the time of rapamycin addition.

We examined the effect of cycloheximide addition after doxycycline removal on BiFC complex formation. Cycloheximide added to cells after doxycycline removal attenuated BiFC complex formation as effectively as it attenuated BiFC complex formation by constitutively expressed fusion proteins (Fig. 7E). These results corroborate the interpretation that inhibitors of protein synthesis attenuated BiFC complex formation by mechanisms unrelated to the inhibition of fusion protein synthesis.

Effects of agents that interfere with protein folding on BiFC complex formation

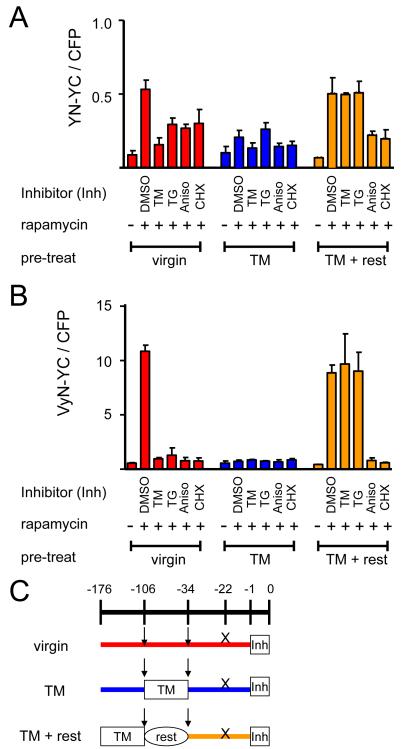

The association of the fluorescent protein fragments is conceptually related to protein folding since the correct secondary structure elements must be brought together to produce both BiFC complexes and native fluorescent proteins. The differences in constitutive and inducible BiFC complex formation by the YN, VN and VyN fusions, and the effect of temperature on the inducibility of BiFC complex formation by the VyN fusion (Fig. 2) are consistent with the hypothesis that protein folding affected BiFC complex formation. To examine potential effects of agents that induce protein folding stress on BiFC complex formation, we monitored BiFC complex formation in cells treated with tunicamycin or thapsigargin. These agents inhibit protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum, resulting in an unfolded protein response. The unfolded protein response changes the cellular protein folding environment and affects also cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins 32; 33. BiFC complex formation by the nuclear FKBP-YN and FRB-YC fusions was reduced 2–10 fold in cells treated with these agents (Fig. 8A and 8B). A similar decrease in BiFC complex formation was observed in cells treated with DTT (data not shown). These agents had no detectable effects on the fluorescence intensities of cells that expressed intact YFP (data not shown) and did not inhibit FKBP-FRB association as measured by activation of reporter gene transcription (Fig. S5B, see supporting results and discussion).

Figure 8. Effects of agents that induce acute and chronic protein folding stress on BiFC complex formation by FKBP and FRB fused to different fluorescent protein fragments.

Cells that expressed (A) FKBP-YN and FRB-YC or (B) FKBP-VyN and FRB-YC were analyzed either without pre-treatment (virgin), after 3 days of culture with 25 ng/ml tunicamycin (TM) or after 3 days of culture with tunicamycin followed by 3 days of culture without tunicamycin (TM + rest). An hour before rapamycin induction, the cells were treated with 1 μg/ml tunicamycin (TM), 50 ng/ml thapsigargin (TG), 25 μg/ml anisomycin (Aniso), or 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX). The cells were harvested 3 hours after rapamycin induction and analyzed by flow cytometry. The bar graph shows the mean ratio of BiFC to CFP fluorescence. (C) Diagram depicting the experimental protocol used in parts A and B. The arrows indicate splits of the cells and the X indicates the time plasmids were transfected into the cells.

Acute treatment with tunicamycin or thapsigargin induces apoptotic pathways, whereas chronic treatment with low concentrations of these agents induces adaptive responses that protect cells from protein folding stress 32. To determine if the inhibition of BiFC complex formation was associated with protein folding stress, we pre-treated cells with a low concentration of tunicamycin for three days and examined the effects of inhibitors of protein folding and synthesis on BiFC complex formation 33 and 105 hours after removing tunicamycin. Rapamycin-inducible BiFC complex formation was markedly reduced 33 hours after pre-treatment (Fig. 8A and 8B). 105 hours after pre-treatment, rapamycin-inducible BiFC complex formation had fully recovered, and was resistant to tunicamycin and thapsigargin treatment. Tunicamycin pre-treatment did not prevent the attenuation of BiFC complex formation by inhibitors of protein synthesis. Reversal of unfolded protein response-mediated inhibition of BiFC complex formation by activation of adaptive pathways is consistent with a role for the cellular protein folding environment in BiFC complex formation.

DISCUSSION

BiFC analysis detected FKBP-FRB complex formation within 10 minutes after inducer addition in individual cells. This rivals the rates of detection of the same interaction by complementation assays that depend on enzymatic amplification (β-galactosidase, DHFR, β-lactamase, luciferases) in cell populations 24; 26; 31; 34; 35; 36. The latter methods require exogenous substrates that may not have equal access to all subcellular compartments. The diffusible products of these enzymes also do not provide information about the subcellular localization of the complexes. The rapid detection of the FKBP-FRB interaction using the BiFC assay was possible because of the low background signal produced by FKBP-YN and FRB-YC fusions in the absence of inducer. The kinetics of BiFC complex formation were proportional to the concentrations of the fusion proteins, suggesting that association of the fluorescent protein fragments was the rate-limiting step in BiFC complex formation over a wide range of fusion protein concentrations.

Fragments of different fluorescent proteins fused to FKBP and FRB produced different relative levels of constitutive and inducible BiFC complexes. The lower inducibility of BiFC complex formation by some fluorescent protein fragments (notably the N-terminal fragment of Venus) was due in large part to efficient BiFC complex formation by these fusion proteins in the absence of inducer. The constitutive association of these fluorescent protein fragments could be due to association of the fragments independent of the FKBP and FRB fusions or it could reflect weak interactions of FKBP and FRB in the absence of inducer. The VyN chimera exhibited inducible fluorescence complementation at 37°C, but constitutive BiFC complex formation at 30°C. Constitutive BiFC complex formation correlated with faster and more robust folding of the fluorescent proteins from which the fragments were derived. Venus folds more rapidly than YFP and its folding is less sensitive to elevated temperature 14. We suggest that the differences in the relative levels of constitutive and inducible BiFC complex formation by different fluorescent protein fragments were caused by different rates of association of the fluorescent protein fragments (see below).

It is likely that many proteins whose interactions are regulated also produce some constitutive complexes. Efficient trapping of such constitutive complexes can prevent detection of the inducibility of complex formation. Our results demonstrate that the choice of fluorescent protein fragments can affect the results from BiFC analysis of protein interactions. They also urge caution when using fusions to the N-terminal fragment of Venus for BiFC analysis of protein interactions. The N-terminal fragment of YFP is recommended when minimal spontaneous background fluorescence is required and the VyN chimera is recommended when maximal fluorescence intensity is necessary and spontaneous BiFC complex formation is not a concern (for a comparison with results from previous studies using fragments of Venus, please see supporting results and discussion).

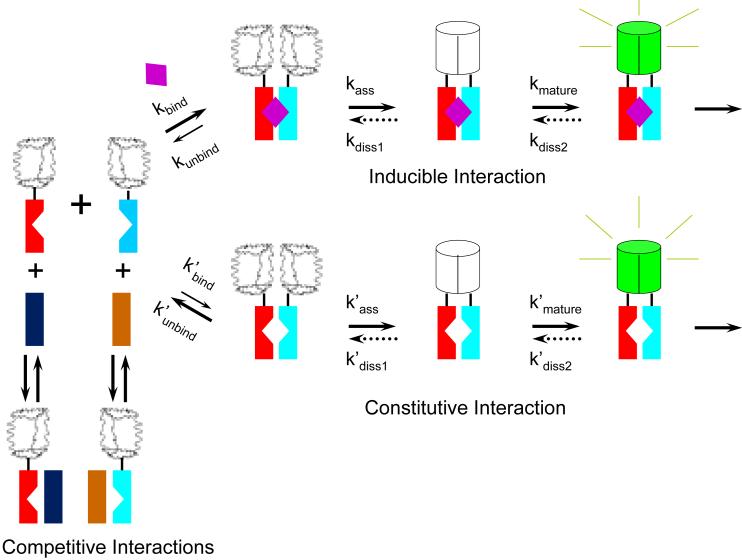

Taken together, our results suggest that several multi-step pathways affect BiFC complex formation in living cells (Fig. 9). One pathway is mediated by inducible FKBP-FRB association, a second by constitutive association of the fusion proteins, and a third by competitive interactions by alternative partners with the fusion proteins. Although our results do not allow determination of the kinetics of each step in these pathways in living cells, we can make some inferences about the effects of some of the steps on the dynamics of BiFC complexes. Rapamycin binding was relatively fast (kbind > 0.1 min−1) since the lag phase in BiFC complex formation was less than 10 minutes. The protracted increase in fluorescence following rapamycin addition indicates that the combined rates of fragment association and fluorophore maturation were considerably slower [min(kass, kmature) < 0.01 min−1]. It is likely that cycloheximide inhibited association of the fluorescent protein fragments and not fluorophore maturation since its effect was delayed when it was added immediately before rapamycin. If this is the case, the half-time of maturation was approximately 60 minutes (kmature ≈ 0.01 min−1). This rate is consistent with that measured previously for BiFC complex maturation in vitro by YFP fragments fused to the bZIP domains of Fos and Jun 4. However, this rate is considerably slower than the virtually instant fluorescence observed upon mixing fluorescent protein fragments conjugated to complementary oligonucleotides 17. This difference could be due to the difference in the fluorescent protein fragments used, but is more likely due to the difference between fusion proteins used in the former two cases and fragments of fluorescent proteins chemically conjugated to oligonucleotides used in the latter case.

Figure 9. Model for the pathways that affect inducible and constitutive BiFC complex formation.

The diagrams represent intermediates in the pathways for BiFC complex formation. Wavy shapes represent unfolded fluorescent protein fragments whereas cylinders represent folded BiFC complexes. The rates of rapamycin binding (kbind), fluorescent protein fragment association (kass), fluorophore maturation (kmature) and potential BiFC complex dissociation (kdiss1 and kdiss2) depend on the identities of the fluorescent protein fragment fusions and are discussed in the text. The putative dissociation (dotted arrows), if it occurs, is unlikely to follow the same pathway as complex formation and could produce fluorescent protein fragments that are chemically distinct from the precursors for BiFC complex formation. The notched rectangles represent FKBP and FRB. The un-notched rectangles represent cellular proteins that can form complexes with the fusion proteins. The purple diamond represents rapamycin.

The concentrations of rapamycin and AP21967 required for BiFC complex formation by all fluorescent protein fragments tested correlated with their binding affinities and effective concentrations in other cellular assays 28; 29. In the case of complementation by fragments of other proteins, the rapamycin concentration-dependence has been interpreted to demonstrate that protein fragment association does not affect the affinity or dynamics of the interaction between the fusion proteins compared to FKBP and FRB alone 26; 31. However, the effects of inducer concentration on complementation do not necessarily reflect the affinity of the complex formed by the fusion proteins for the inducer because proteins in cells are not at equilibrium. In the case of BiFC complex formation, we propose that the efficiency of complementation by the fluorescent protein fragments is determined by the proportion of complementary fluorescent protein fragments that are present in the same complex rather than in complexes with cellular interaction partners (Fig. 9, competitive interactions). This ratio is determined among other things by the affinity of the proteins fused to the fluorescent protein fragments for each other relative to alternative partners. In the case of FKBP and FRB, this depends on the concentration of rapamycin or other inducers. Thus, differences in BiFC complex formation by the same fusion proteins under different conditions can be used to infer differences in the efficiencies of association of proteins lacking the fluorescent protein fragments, but these differences cannot be used to infer the affinities of the proteins or their dynamics.

FK506 treatment did not disrupt pre-formed BiFC complexes within 8 hours of treatment. These results suggest that the rate of dissociation of BiFC complexes formed by FKBP and FRB fusions was very slow (kdiss(overall)<0.001 min−1). We cannot define the step in the pathway that is responsible for the stabilization of BiFC complexes in cells based on our data. However, we favor the interpretation that the rate of this step depends on the identity of the fluorescent protein fragments since this model is consistent with our observation that the specificity of BiFC complex formation varies for fusions to different fluorescent protein fragments. The lack of detectable dissociation by BiFC complexes formed by FKBP and FRB fusions in cells treated with FK506 is consistent with the high stability of BiFC complexes formed by YFP fragments fused to the bZIP domains of Fos and Jun in vitro 4. These results contrast with the rapid dissociation of BiFC complexes formed by fluorescent protein fragments conjugated to oligonucleotides in vitro 17. This difference could be due to the identities of the fluorescent protein fragments, differences between interactions mediated by proteins versus nucleic acids or differences between the conditions in cells and those used in vitro. It is also possible that FK506 treatment does not disrupt interactions between FKBP and FRB in cells regardless of the fluorescent protein fragments. The latter interpretation is consistent with the statistically insignificant effect of FK506 addition after rapamycin treatment on the activity of a reporter gene regulated by FKBP-FRB interaction (Fig. S5, see supporting results and discussion), but contradicts previous reports of FKBP-FRB dissociation in cells 31. Given the large interaction interface formed by folding of the two fluorescent protein fragments in the BiFC complex, it is likely that BiFC complex formation in cells stabilizes the association of many interaction partners fused to fluorescent protein fragments.

The lack of detectable dissociation of BiFC complexes formed by FKBP and FRB fusions in cells suggests that BiFC complex formation is energetically favorable. Nevertheless, YFP fragments did not produce BiFC complexes efficiently when they were fused to non-cognate interaction partners or to FKBP and FRB in cells cultured in the absence of inducer (Fig. 4). The most plausible interpretation of these data is that the efficiency of BiFC complex formation is determined in part by kinetic competition among alternative interaction partners rather than exclusively by thermodynamic stability. Competition by alternative interaction partners is predicted to reduce the proportion of non-cognate partners that interact with each other, and thereby to reduce their rate of BiFC complex formation (Fig. 9, competitive interactions). Moreover, interactions with cellular proteins can localize the fluorescent protein fragments to different subcellular compartments or prevent their association through steric interference.

The difference between the relative efficiencies of BiFC complex formation by the N-terminal fragments of YFP and Venus fused to non-cognate versus cognate interaction partners can be explained by a difference in the rates of stable association of these fragments with the complementary C-terminal fragment. When the rate of fragment association is lower than the rate of exchange among alternative interaction partners, and intermediates in the pathway are not depleted, then stabilization of BiFC complexes by fluorescent protein fragment association will not significantly alter the relative amounts of BiFC complexes formed by cognate and non-cognate interaction partners. In contrast, when the rate of fluorescent protein fragment association is high, and intermediates in the pathway can be depleted and stabilization of BiFC complexes results in an increase in the relative amount of complexes formed by non-cognate interaction partners. The specificity of BiFC analysis therefore depends in part on kinetic rather than exclusively thermodynamic control of BiFC complex formation. Competition by interactions with endogenous proteins is an important determinant of the specificity of BiFC complex formation.

The difference between the effects of the N-terminal fragments of Venus and YFP on the specificities of BiFC complex formation by fusions to FKBP and FRB versus to bMyc and Max indicates that this effect depends on the interaction partners. One potential explanation for the difference is that FKBP and FRB have a low efficiency of association in the absence of rapamycin whereas bMyc does not interact with Max lacking the leucine zipper. An alternative interpretation is that the relative rates of association of the fluorescent protein fragments and the interaction partners differ between these complexes. In either case, BiFC complex formation by the N-terminal fragment of Venus with YC can stabilize FKBP-FRB association in the absence of rapamycin more efficiently than bMyc-Max association in the absence of the leucine zipper.

Many fluorescent protein fragment fusions undergo irreversible mis-folding in vitro in the absence of the complementary protein fragment. However, fluorescent protein fragments fused to FKBP retained their ability to form BiFC complexes in cells for several hours after synthesis. It is possible that their competence to form BiFC complexes is sustained by an association with cellular chaperonins.

The attenuation of BiFC complex formation by tunicamycin, thapsigargin or DTT treatment indicates that agents that interfere with protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum can affect BiFC complex formation by FKBP and FRB fusions in the nucleus. The unfolded protein response induced by these agents can activate both adaptive and apoptotic pathways involving changes in chaperonin levels and signaling 32; 33. Since pre-treatment of cells with sub-acute levels of tunicamycin protects BiFC complex formation from inhibition by these agents, the acute (apoptotic) unfolded protein response is inhibitory to BiFC complex formation whereas the chronic (adaptive) response is protective. Since the unfolded response has a wide range of effects on cells, it is not possible to unambiguously establish that the effects on BiFC complex formation were due to changes in protein folding. Agents that induce the unfolded protein response had no detectable effect on transcription activation by FKBP and FRB fusions, suggesting that they did not affect FKBP-FRB interaction independent of the fluorescent protein fragments (Fig. S5). Factors and conditions that influence the cellular protein folding environment are therefore likely to affect BiFC complex formation by other fusion proteins as well.

Inhibitors of protein synthesis attenuated BiFC complex formation. However, the kinetics of the attenuation and the recovery of BiFC complex formation were slower than the rates of inhibition and recovery of protein synthesis established previously 37. Significantly, cycloheximide attenuated BiFC complex formation by pre-existing fusion proteins under conditions where the synthesis of new fusion proteins was repressed. Taken together, these results indicate that inhibitors of protein synthesis attenuate BiFC complex formation through mechanisms unrelated to their effects on fusion protein synthesis. It is possible that truncated peptides or other changes caused by the inhibition of translation resulted in protein folding stress or perturbation of chaperonin activity. Geldanamycin, an inhibitor of hsp90 family chaperonins, did not affect rapamycin-inducible BiFC complex formation by FKBP and FRB fusions. The rapid inhibition of BiFC complex formation by agents that perturb biosynthesis of native proteins suggests that the effects of pharmacological agents on BiFC complex formation should be interpreted with care.

The N-terminal fragments of YFP and Venus differ by three amino acid substitutions (F46L, F64L and M153T). The single amino acid substitution in VyN (T153M) compared to Venus is near the end of this fragment. The side-chain of this residue is solvent-exposed and located at one end of the β barrel (Movie 1). The ten-fold effects of this amino acid substitution on both spontaneous and inducible BiFC fluorescence indicate that relatively subtle changes in amino acid sequence can have large effects on BiFC complexes. The two phenylalanine residues in YFP that are substituted by leucines in Venus and in VyN pack within the core of the β-barrel. The phenylalanine residues in YFP may retard folding because of their restricted rotation or the stabilization of non-native folding intermediates. The effects of these amino acid substitutions on the BiFC assay suggest that the characteristics of the BiFC assay can be adapted for specific purposes by identification of new variants of fluorescent protein fragments.

Many fluorescent protein fragments that form BiFC complexes with divers spectral characteristics and fluorescence intensities have been identified 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9; 10. Among the fluorescent protein fragments tested here, fragments of YFP had the lowest level of spontaneous association and the highest induction ratio when fused to FKBP and FRB. Fragments of CFP had similar inducibility of BiFC complex formation based on visualization by microscopy, but this could not be accurately quantified using our flow cytometry instruments. The N-terminal fragment of Venus produced high constitutive fluorescence and a lower induction ratio in combination with different C-terminal fragments. The M153 substitution in the Venus fragment reduced, but did not eliminate, constitutive BiFC complex formation and produced an induction ratio comparable to that of the N-terminal fragment of YFP at 37 °C. The specificity of BiFC complex formation by this fragment was affected by temperature. The cellular environment affects BiFC complex formation by all fluorescent protein fragments, and it is likely that the proteins that are fused to the fragments also affect their characteristics. It is possible that fluorescent protein fragments with more favorable characteristics can be indentified by testing additional fragments of naturally occurring or engineered fluorescent protein variants. However, artificial or evolutionary selection in the context of an intact fluorescent protein does not necessarily improve the performance of the protein fragments in the BiFC assay. Our data show that enhanced folding can reduce the performance of fluorescent protein fragments in BiFC analysis. The effects of the cellular environment on BiFC complex formation also indicate that BiFC complex formation in vitro may not faithfully reflect protein interactions in cells. Direct selection for increased specificity and dynamic responsiveness of the BiFC assay in living cells is a more appropriate strategy for the identification of fluorescent protein fragments with improved characteristics. The inducible BiFC assay developed here and the rapid and quantitative measurement of fluorescence in individual cells provide tools for this effort.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid construction

Sequences encoding amino acids residues 1–154 of YFP (YN), CFP (CN), amino acid residues 1–155 of Venus (VN), and as well as amino acids residues 155–238 of YFP (YC) and CFP (CC) 4; 5 were fused to sequences encoding FKBP12 and FRB. The VyN chimera contained residues 1–155 of Venus with the exception for M153 from YFP 9. These sequences encoding fusion proteins were cloned downstream of the constitutive CMV promoter in pBiFC vectors as described in supporting materials and methods. The sequences encoding YN, VN and YC were also fused to sequences encoding the bHLHZIP domain of Myc and Max as described 11. To control the timing of FKBP-YN expression, the sequence encoding the fusion protein was inserted in plasmid pUHrTG2-1 carrying a doxycycline-regulated promoter 38.

Microscopy and flow cytometry analysis of bimolecular fluorescence complementation

COS-1 cells cultured and transfected as described in supporting materials and methods were treated as described in each experiment. The fluorescence was imaged by microscopy as described 4; 11. Cells that were imaged live were cultured in CO2 independent medium. BiFC complexes formed by YN, VN and VyN fusions with YC or CC were imaged by excitation at 500 nm and detecting emission at 535 nm. BiFC complexes formed by CN fusions with CC were imaged by excitation at 436 nm and detecting emission at 470 nm. For flow cytometry, the cells were fixed at the times indicated and their fluorescence intensities were measured as described in supporting materials and methods. The BiFC fluorescence intensity was normalized by the CFP fluorescence to correct for possible differences in transfection efficiency. In some experiments (Fig. 5), uncorrected mean BiFC fluorescence was used to avoid potential effects of the treatments on the normalization. Only cells that had BiFC or CFP fluorescence above the background signal of non-transfected cells were included in the calculations. For additional information about the plasmids, cells, antibodies and chemicals used as well as protocols used for microscopy and flow cytometry, please see supporting materials and methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jason Gestwicki, Tom Rutkowski and David Adams for valuable advice, Dawen Cai for assistance with construction of plasmids encoding the FKBP and FRB fusions, Haiyuan Ding for construction of the plasmid encoding the bHLHZIP domain of Myc fused to the N-terminal fragment of Venus and members of the Kerppola laboratory for constructive criticisms. The research was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM086213).

References

- 1.Kerppola TK. Visualization of molecular interactions by fluorescence complementation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nrm1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 2006;312:217–24. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfleger KD, Eidne KA. Illuminating insights into protein-protein interactions using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) Nat Methods. 2006;3:165–74. doi: 10.1038/nmeth841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu CD, Chinenov Y, Kerppola TK. Visualization of interactions among bZIP and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol Cell. 2002;9:789–98. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu CD, Kerppola TK. Simultaneous visualization of multiple protein interactions in living cells using multicolor fluorescence complementation analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:539–545. doi: 10.1038/nbt816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rackham O, Brown CM. Visualization of RNA-protein interactions in living cells: FMRP and IMP1 interact on mRNAs. EMBO J. 2004;23:3346–3355. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shyu YJ, Liu H, Deng XH, Hu CD. Identification of new fluorescent protein fragments for bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis under physiological conditions. Biotechniques. 2006;40:61–66. doi: 10.2144/000112036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jach G, Pesch M, Richter K, Frings S, Uhrig JF. An improved mRFP1 adds red to bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Nat Methods. 2006;3:597–600. doi: 10.1038/nmeth901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saka Y, Hagemann AI, Piepenburg O, Smith JC. Nuclear accumulation of Smad complexes occurs only after the midblastula transition in Xenopus. Development. 2007;134:4209–18. doi: 10.1242/dev.010645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ottmann C, Weyand M, Wolf A, Kuhlmann J. Applicability of superfolder YFP bimolecular fluorescence complementation in vitro. Biol Chem. 2009;390:81–90. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grinberg AV, Hu CD, Kerppola TK. Visualization of Myc/Max/Mad family dimers and the competition for dimerization in living cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4294–4308. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4294-4308.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cody CW, Prasher DC, Westler WM, Prendergast FG, Ward WW. Chemical structure of the hexapeptide chromophore of the Aequorea green-fluorescent protein. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1212–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00056a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid BG, Flynn GC. Chromophore formation in green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6786–91. doi: 10.1021/bi970281w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagai T, Ibata K, Park ES, Kubota M, Mikoshiba K, Miyawaki A. A variant of yellow fluorescent protein with fast and efficient maturation for cell-biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:87–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt0102-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo YJ, Rebecchi M, Scarlata S. Phospholipase C beta(2) binds to and inhibits phospholipase C delta(1) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1438–1447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407593200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magliery TJ, Wilson CGM, Pan WL, Mishler D, Ghosh I, Hamilton AD, Regan L. Detecting protein-protein interactions with a green fluorescent protein fragment reassembly trap: Scope and mechanism. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:146–157. doi: 10.1021/ja046699g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demidov VV, Dokholyan NV, Witte-Hoffmann C, Chalasani P, Yiu HW, Ding F, Yu Y, Cantor CR, Broude NE. Fast complementation of split fluorescent protein triggered by DNA hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2052–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511078103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerppola TK. Visualization of molecular interactions using bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis: Characteristics of protein fragment complementation. Chemical Society Reviews. 2009;38:2876–2886. doi: 10.1039/b909638h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J-R, Craggs TD, Christodoulou J, Jackson SE. Stable Intermediate States and High Energy Barriers in the Unfolding of GFP. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2007;370:356–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown EJ, Albers MW, Shin TB, Ichikawa K, Keith CT, Lane WS, Schreiber SL. A mammalian protein targeted by G1-arresting rapamycin-receptor complex. Nature. 1994;369:756–8. doi: 10.1038/369756a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiu MI, Katz H, Berlin V. RAPT1, a mammalian homolog of yeast Tor, interacts with the FKBP12/rapamycin complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12574–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabatini DM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Lui M, Tempst P, Snyder SH. RAFT1: a mammalian protein that binds to FKBP12 in a rapamycin-dependent fashion and is homologous to yeast TORs. Cell. 1994;78:35–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90570-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberles SD, Diver ST, Austin DJ, Schreiber SL. Inducible gene expression and protein translocation using nontoxic ligands identified by a mammalian three-hybrid screen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7825–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi F, Charlton CA, Blau HM. Monitoring protein-protein interactions in intact eukaryotic cells by beta-galactosidase complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:8405–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stockwell BR, Schreiber SL. Probing the role of homomeric and heteromeric receptor interactions in TGF-beta signaling using small molecule dimerizers. Curr Biol. 1998;8:761–70. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Remy I, Michnick SW. Clonal selection and in vivo quantitation of protein interactions with protein-fragment complementation assays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5394–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulmurugan R, Gambhir SS. Novel fusion protein approach for efficient high-throughput screening of small molecule-mediating protein-protein interactions in cells and living animals. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7413–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banaszynski LA, Liu CW, Wandless TJ. Characterization of the FKBP.rapamycin.FRB ternary complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4715–21. doi: 10.1021/ja043277y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bayle JH, Grimley JS, Stankunas K, Gestwicki JE, Wandless TJ, Crabtree GR. Rapamycin analogs with differential binding specificity permit orthogonal control of protein activity. Chem Biol. 2006;13:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bierer BE, Mattila PS, Standaert RF, Herzenberg LA, Burakoff SJ, Crabtree G, Schreiber SL. Two distinct signal transmission pathways in T lymphocytes are inhibited by complexes formed between an immunophilin and either FK506 or rapamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9231–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remy I, Michnick SW. A highly sensitive protein-protein interaction assay based on Gaussia luciferase. Nat Methods. 2006;3:977–979. doi: 10.1038/nmeth979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutkowski DT, Arnold SM, Miller CN, Wu J, Li J, Gunnison KM, Mori K, Sadighi Akha AA, Raden D, Kaufman RJ. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baltzis D, Pluquet O, Papadakis AI, Kazemi S, Qu LK, Koromilas AE. The eIF2alpha kinases PERK and PKR activate glycogen synthase kinase 3 to promote the proteasomal degradation of p53. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31675–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paulmurugan R, Umezawa Y, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive imaging of protein-protein interactions in living subjects by using reporter protein complementation and reconstitution strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242594299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wehrman T, Kleaveland B, Her JH, Balint RF, Blau HM. Protein-protein interactions monitored in mammalian cells via complementation of beta -lactamase enzyme fragments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3469–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062043699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spotts JM, Dolmetsch RE, Greenberg ME. Time-lapse imaging of a dynamic phosphorylation-dependent protein-protein interaction in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15142–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232565699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]