Abstract

More than 100 cyclic peptides harboring heterocyclized residues are known from marine ascidians, sponges and different genera of cyanobacteria. Here, we report an assembly line responsible for the biosynthesis of these diverse peptides, now called cyanobactins, both in symbiotic and free-living cyanobacteria. By comparing five new cyanobactin biosynthetic clusters, we could produce the prenylated antitumor preclinical candidate, trunkamide, in E. coli culture using genetic engineering.

Marine ascidians are an excellent source of natural products1, including ~60 cyclic peptides of the patellamide class, which constitute about 6% of natural products isolated from ascidians (MarinLit). Patellamide-containing ascidians harbor cyanobacterial symbionts, Prochloron spp., that have eluded cultivation. Recently, it was shown that Prochloron didemni is responsible for synthesizing cyclic peptides2, 3 that were originally isolated from the host ascidians4, 5. Surprisingly, single point mutations in short cassettes in the biosynthetic gene clusters resulted in a diverse product library6. By mimicking this natural evolution, a new cyclic peptide was made using rational genetic engineering (1)6. A homologous pathway was found in the genome of a free-living cyanobacterium encoding a new natural product, trichamide (2)7.

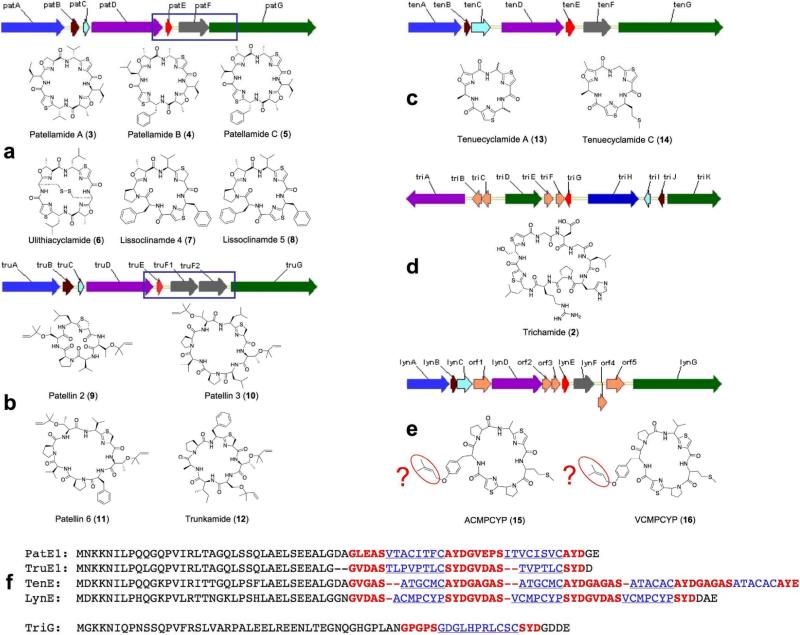

The patellamides (3–8) are biosynthesized through a unique ribosomal route2 with some similarity to microcin pathways (Fig. 1)8. The products’ amino acid sequence is encoded directly on a precursor peptide, PatE (Fig. 1f)2. Short cassettes within the precursor peptide gene are hypervariable, resulting in a natural combinatorial library of cyclic peptides6. Outside of these cassettes, all known patellamide pathways are 99 % identical to each other over their entire lengths (~ 11 kb)6. The following biosynthetic hypothesis was proposed2, 7. The encoding cassettes are flanked by recognition sequences that recruit enzymes for post-translational modifications. Among those are two proteases, PatA and PatG, which catalyze N-C terminal cyclization. PatD is responsible for heterocyclization of cysteine to thiazoline, which is then oxidized to thiazole by an oxidase domain in PatG. PatF may be involved in serine and threonine heterocyclization to oxazoline, among other possibilities. The proteins PatB and PatC were shown to be nonessential6. The above hypothesis2, 7 and alternatives9 remain to be tested.

Figure 1. Cyanobactin pathways in cyanobacteria.

Five cyanobactin gene clusters are represented by arrows, while their associated small molecule products are shown at right. Conserved genes are indicated as identically colored arrows in the pathways. Underneath each gene cluster is a light micrograph of the producing cyanobacterial species. (a), pat cluster and biosynthetically identified products from the patellamide, lissoclinamide and ulithiacyclamide families of compounds. (b), tru cluster and identified products from the patellin and trunkamide families. The part of the pathway where pat and tru differ is boxed in blue. (c), ten and identified products tenuecyclamide A and C. (d), tri cluster and identified product trichamide. (e), lyn cluster and predicted products. (f), The amino acid sequences of the encoded cyanobactin products are shown in blue and underlined, while probable recognition sequences are shown in red and bold. PatE1 encodes for patellamides C and A; TruE1 encodes for patellins 2 and 3; TenE encodes for two tandem copies of each of tenuecyclamides C and A; LynE encodes for two predicted products; TriG encodes for trichamide. The Trichodesmium erythraeum photo in (d) is by John Waterbury, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the Lyngbya aestuarii photo in (e) is credited to Alehandro Lopez (CIBNOR), Mark Schneegurt (Wichita State University), and Cyanosite (www-cyanosite.bio.purdue.edu).

Numerous patellamide relatives have been isolated from marine invertebrates, including some with unprecedented chemical motifs. For example, a large number of patellins and derivatives have been isolated from ascidians (9–12)10, 11. These metabolites are prenylated at serine and threonine rather than being heterocyclized and were proposed to be of cyanobacterial origin (Supplementary Fig. S1 online). In addition, heterocyclized cysteine residues remain at the reduced thiazoline stage10, 11. Like patellamides, the patellin family has been isolated only from Prochloron-containing ascidians. They are known to be cytotoxic, and one member of this group, trunkamide, was a preclinical antitumor candidate12. Many patellamide-like compounds have also been reported from free-living cyanobacteria13. Examples include the tenuecyclamides (13, 14), which potently inhibit the division of sea urchin embryos14. Because tenuecyclamide-like peptides are common in free-living cyanobacteria, and because of the prenylation event found in trunkamide and related ascidian compounds, we undertook a study of their biosynthesis. These pathways have conserved features that warrant their inclusion in a new family of cyanobacteria-specific compounds, the cyanobactins.

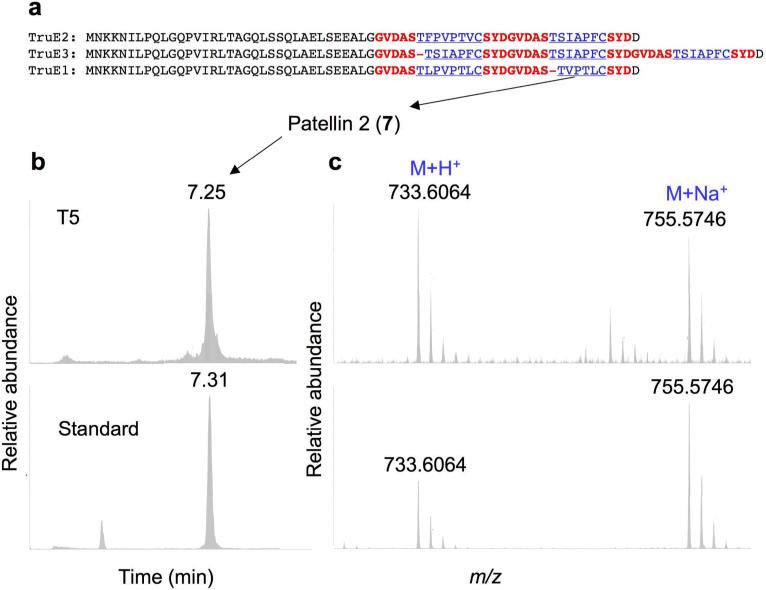

In order to determine whether Prochloron bacteria synthesize prenylated peptides within ascidians, we collected several candidate ascidians in Fiji and the Solomon Islands (Supplementary Methods online). After chemical screening, we found prenylated cyclic peptides in three samples: Lissoclinum patella and Didemnum molle from adjacent locations in the Solomon Islands; and L. patella from Fiji. Prochloron cells were enriched from the Fiji sample and a fosmid library was constructed, leading to the discovery of the patellin pathway tru on a single fosmid (Fig. 1b). This fosmid was sequenced and found to contain a patellamide-like biosynthetic pathway directly encoding patellins 2 and 3 on a precursor gene (similar to patE in the pat cluster, Fig. 1f). This observation was consistent with the chemical analysis of the ascidian sample. To further demonstrate that the tru cluster is necessary and sufficient for the biosynthesis of the prenylated products, the cluster was transferred to E. coli. The ~11 kb cluster was amplified by PCR, cloned, and expressed in E. coli. The fractionated expression broth was analyzed by mass spectrometry and compared to authentic standards. Both patellins 2 and 3 — isolated originally from the ascidian sample — were detected in an approximate yield of 100 μg L–1 in three separate experiments (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. S2 online). These results show that the tru cluster is responsible for the biosynthesis of the patellins, including the prenylation. To further demonstrate the involvement of the cluster in patellin 2 and 3 biosynthesis and to develop tools for pathway engineering, we constructed a knockout vector using the tru expression plasmid in which the truF1 gene was cleanly replaced with a streptomycin resistance gene (Supplementary Fig. S3 online). The resulting construct was transferred to E. coli, and the extract was analyzed for the presence of cyclic peptides. No products were detected from a 10 L fermentation, further validating the tru operon.

Figure 2. The tru pathway to patellins and trunkamide.

(a), The precursor peptide variants TruE1-E3 are shown. Product-coding sequences are in blue and underlined while recognition sequences are in red and bold. TruE1 encodes for patellins 2 and 3, TruE2 encodes for patellin 6 and trunkamide, and TruE3 encodes for three copies of trunkamide. (b) and (c), The tru pathway was expressed in E. coli and broth was analyzed by high resolution mass spectrometry. Top: E. coli broth; bottom: standard of patellins 2 and 3. Data are shown for patellin 2 and a similar pattern was observed for patellin 3 (Supplementary Fig. S3). (a), A total ion chromatogram filtered for m/z = 733 corresponding to patellin 2 is shown. Both the standard and the recombinant product eluted at exactly the same time. (b), The mass of the recombinant product exactly matched that of the standard to four decimal places (these masses do not correspond to the reported exact mass of patellin 2 due to the lack of an internal standard).

The precursor peptide TruE (Fig. 1f) directly encodes the amino acid sequence of the octapeptide patellin 3 and the hexapeptide patellin 2. Putative recognition sequences were similar to those found in the patellamide precursor protein, PatE (Fig. 1f). However, the presence of products with different sizes (octamer and hexamer) on a single precursor had not been observed in any of the 29 patellamide pathway variants previously described6.

Comparative sequence analysis of the tru cluster shows that it is syntenic to pat (Fig. 1a,b). The two clusters share 98.2–99.1% DNA sequence identity over half of the pathway. A region with lower identity spans the last 980 bp of truD, truE, truF1, truF2 and the first 1806 nucleotides of truG. In this 5.8 kb region (Fig. 1a,b), predicted proteins share 41–74% identity with their homolgs in the pat cluster. However, two major differences were observed that are consistent with the unique chemical features of the patellins. First, TruG does not contain an oxidase domain, unlike its patellamide homolog, PatG. This is rationalized by the fact that patellins harbor thiazolines, while patellamides are oxidized to thiazoles. Second, two copies of truF are found adjacent to each other and syntenic to the location of patF. TruF1 and TruF2 are 41 and 46% identical to PatF, respectively, but only 35% identical to each other. truD and patD are virtually identical throughout their first 1360 bps (97% identity in the DNA and the resulting amino acid sequence). However, in their last 980 bp, the genes only share 72% identity. Because the pat and tru clusters were shown to be sufficient for the biosynthesis of the patellamides2 and the patellins, respectively, detailed comparative analysis sheds light on the individual proteins’ functional evolution. For example, the main differences between the two clusters are found in patF / (truF1-truF2) and patD / truD (3’ end). We hypothesize that at least one set of these proteins is involved in the heterocyclization of serine and threonine in the patellamides and their prenylation in the patellins.

In the patellamides, hypervariability in small cassettes in PatE lead to natural cyclic peptide libraries6. To see whether this is also the case for TruE, variants were cloned from ascidian samples containing patellins and trunkamide, revealing two novel genes: truE2 and truE3 (Fig. 2a). While TruE2 encodes the octapeptide patellin 6 and the heptapeptide trunkamide, TruE3 encodes 3 copies of trunkamide, representing the first PatE variant encoding more or less than 2 product peptides. PCR and sequencing experiments were used to compare the tru1 and tru2 clusters and showed that they are identical, with the exception of hypervariable cassettes in truE in the exact product-coding regions (Supplementary Fig. S4 online). These results show that the evolution of the tru pathway mimicked that of the pat pathways. Single point mutations in short cassettes generated a library of prenylated cyclic peptides.

To demonstrate the engineering potential of the cloned tru pathway, we used homologous recombination in yeast to replace truE1 with truE2. A ~4kb piece harboring truE2 was amplified by PCR and used to cross over the tru1 pathway. The recombinant construct now contained truE2 encoding patellin 6 and trunkamide, in place of the original patellins 2 and 3. In an E. coli fermentation experiment, no peaks corresponding to patellins 2 or 3 were detected while a new peak for trunkamide was clearly observed and compared to authentic standards using high resolution mass analysis (Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6 online).10 These experiments serve as a proof of principle for our ability to engineer the tru pathway for the production of clinically important compounds. Recombination also allows the functional rescue of sequences from environmental DNA that may be too rare or degraded for traditional cloning approaches.

To identify homologs from free living cyanobacteria and observe further functional evolution, we studied the tenuecyclamide-producing strain, Nostoc spongiaeforme var. tenue14. A homology-based strategy led to the identification of a fosmid containing the ten cluster, a candidate for tenuecyclamide biosynthesis (Fig. 1c). Although the tenuecyclamide- and patellamide-producing strains are distantly related, the ten cluster is highly similar to the pat cluster. It is composed of seven genes encoded on the same strand (tenA to tenG). Most of the ten genes show 70 to 80 % identity to their homologous pat genes at the DNA and protein level with the exceptions of TenC and TenF (~50% identity with pat homologs). A unique feature in the ten cluster is its precursor peptide, TenE, which encodes two copies of the primary amino acid sequence of each of the hexapeptides tenuecyclamide A and C, for a total of four copies (Fig. 1f). The recognition sequences are similar to those found in PatE.

By mining the genome sequence of Lyngbya aestuarii CCY9616, we identified a third patellamide-like pathway type representing a fifth new gene cluster. The lyn cluster contains homologs of all the genes found in the pat cluster (lynA to lynG). However, it contains five additional coding sequences for which no function could be assigned (Fig. 1e). The precursor peptide gene, lynE, was identified and re-annotated (Fig. 1f). From LynE sequences, we have predicted possible new structures (15,16).

Cyanobactins are widespread in cyanobacteria. About 100 probable cyanobactins have been previously described and are widely distributed through taxonomically distant species. Based upon genetic analysis, many more await discovery. This observation places the cyanobactins assembly line reported here as one of the major routes to small molecule biosynthesis in cyanobacteria, after the polyketide synthases and nonribosomal peptide synthetases. While this manuscript was in review, two cyanobactin clusters were reported from two strains of Microcyctis aeruginosa encoding for the biosynthesis of various microcyclamides15, further reinforcing the wide-spread occurrence of this assembly line in cyanobacteria.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health GM071425 and the National Science Foundation EF-0412226. We thank C. Ireland (U. Utah), the University of the South Pacific, the Solomon Islands, and the Republic of the Fiji Islands for providing opportunities to collect marine animal samples used in these studies. S. Meo (U. South Pacific) aided with the collection of L. patella in Fiji. S. Carmeli (Tel-Aviv University) provided the Nostoc culture. J.G. Muller and T. Bugni (U. Utah) helped with mass spectrometry experiments reported in this work. A. Bird and D. Winge (U. Utah) helped with yeast recombination.

Footnotes

Additional methods. Details of experimental methods and results are given in the supplementary section (Supplementary Methods online).

Availability of materials and data. All new sequences have been deposited in GenBank, accession numbers (EU290741-EU290744). Plasmids are available from E.W.S., ews1@utah.edu.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Competing Financial Interests Statement. Some claims in a patent to E.W.S. are supported by this work.

References

- 1.Davidson BS. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1771–1791. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt EW, et al. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501424102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long PF, Dunlap WC, Battershill CN, Jaspars M. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:1760–1765. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ireland CM, Durso AR, Newman RA, Hacker MP. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:1807–1811. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Degnan BM, et al. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:1349–1354. doi: 10.1021/jm00126a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donia MS, et al. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006;2:729–735. doi: 10.1038/nchembio829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudek S, Haygood MG, Youssef DT, Schmidt EW. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006 doi: 10.1128/AEM.00380-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y-M, Milne JC, Madison LL, Kolter R, Walsh CT. Science. 1996;274:1188–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milne BF, Long PF, Starcevic A, Hranueli D, Jaspars M. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:631–638. doi: 10.1039/b515938e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll AR, et al. Aust. J. Chem. 1996;49:659–667. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabriskie TM, Foster MP, Stout TJ, Clardy J, Ireland CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8080–8084. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salvatella X, Caba JM, Albericio F, Giralt E. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:211–215. doi: 10.1021/jo026464s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan LT. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:954–979. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banker R, Carmeli S. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1248–1251. doi: 10.1021/np980138j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziemert N, et al. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:1791–1797. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02392-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.