Abstract

Iron is an essential nutrient for microbes and many pathogenic bacteria depend on siderophores to obtain iron. The mammalian innate immunity protein lipocalin 2 (Lcn2, NGAL, 24p3, Siderocalin) binds the siderophore carboxymycobactin, an essential component of the iron acquisition apparatus of mycobacteria. Here we show that Lcn2 suppressed growth of Mycobacterium avium in culture, and M. avium induced Lcn2 production from mouse macrophages. Lcn2 was also elevated and initially limited the growth of M. avium in the blood of infected mice, but did not impede growth in tissues and during long-term infections. M. avium is an intracellular pathogen. Subcellular imaging of infected macrophages revealed that Lcn2 trafficked to lysosomes separate from M. avium, whereas transferrin was efficiently transported to the mycobacteria. Thus mycobacteria seem to reside in the Rab11+ endocytic recycling pathway, thereby retaining access to nutrition and avoiding endocytosed immunoproteins like Lcn2.

Keywords: Mycobacteria, infection, mouse, iron, Lcn2, transferrin, Rab11

Introduction

Most organisms depend on iron to grow (reviewed in [1]) and many microbes acquire iron from the surroundings is by producing siderophores, small organic compounds with extremely high affinities for ferric ions [2]. We have previously shown that lipocalin 2 (Lcn2, NGAL, 24p3 or Siderocalin) can bind to a number of bacterial siderophore-iron complexes [3, 4]. Lcn2 binds to enterochelin produced by several pathogenic E. coli strains and plays an important role in innate immunity by restricting their growth during infection [5]. Murine Lcn2 has been described as an acute phase protein due to markedly elevated levels in serum and tissues during inflammation [5].

The genus of Mycobacterium contains pathogenic species mainly in the M. tuberculosis complex (M. tuberculosis, M. bovis), but also in the environmental M. avium complex (M. avium subsp. avium, hominissuis, paratuberculosis). The causative agent of tuberculosis, M. tuberculosis, kills close to two million people each year (http://www.who.int/). M. avium is an opportunistic pathogen and a common disseminated bacterial infection in AIDS patients not on antiretroviral therapy [6]. Pathogenic mycobacteria are taken up by macrophages into vacuoles where they survive by blocking phagolysosomal maturation, a complex process involving bacterial manipulations of the host cell trafficking machinery [7-10]. The mycobacterial phagosome contains markers of early endosomes [10-12] and from this location the mycobacteria scavenge iron from endocytosed transferrin or intracellular iron stores by using mycobactin siderophores [11, 13-15]. It has been shown that mycobactin synthetase enzymes are vital for the growth of M. tuberculosis in macrophages [16]. The mycobactins are synthesized in two major forms differing in an acyl substituent group: cell-wall associated mycobactins and water-soluble carboxymycobactins, the latter of which are bound with high affinity by Lcn2 [4, 17]. We therefore undertook this study to evaluate the effect of Lcn2 on M. avium infections in vitro and in vivo, including trafficking of Lcn2 in relation to the mycobacteria in mouse macrophages. We found that Lcn2 did restrict the growth of M. avium, but intracellular mycobacteria seemed to avoid the Lcn2 defense. Imaging revealed that M. avium resided in the Rab11+ endocytic recycling pathway thus avoiding Lcn2 trafficking the lysosomal pathway. Our findings add to the many aspects of an intracellular lifestyle that is of benefit for the mycobacteria.

Methods

Reagents

Recombinant Lcn2 was purified as described in [3]. Polyclonal anti-mouse Lcn2 antibodies 807 and 835 were produced in rabbits immunized with recombinant moLcn2 and affinity purified. Receptor-associated protein (RAP) was kindly provided by Scott Argraves (Medical University of South Carolina, USA). Lcn2 and RAP were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (A488) or A647 according to manufacturer's protocols (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes). Lysotracker Green, Dextran-A488 and transferrin-A546, anti-rabbit Ab-A647, anti-goat Ab-A647, anti-goat Ab-A488 were from Molecular Probes. Polyclonal goat anti-Rab4a Ab (sc26262), rabbit anti-Rab5a Ab (sc309), goat anti-Rab7 Ab (sc10767), goat anti-Rab11a Ab (sc26590) and goat anti-Rab11b (sc26591) were from Santa Cruz.

Mice and cells

All animal work was approved by the local Animal Care Committee (ref.nr. 40/05). Lcn2 deficient mice were as described in [5]; subsequently Lcn2 knockouts were backcrossed 8 times to C57Bl/6. MyD88 and TRIF knockouts were of C57Bl/6 background. C57Bl/6 mice were from Bomholdt (Denmark). BMDM were obtained by culturing bone marrow in RPMI1640 with 20% L929-conditioned medium and 10% fetal calf serum for 7 days before infection or uptake studies.

Mycobacteria

Transformants of the virulent Mycobacterium avium clone 104 were used in all experiments. M. avium 104 expressing firefly luciferase was a kind gift from David R. Sherman [18]. M. avium 104 expressing GFP: pMV306∷gfpmut3 (red-shifted) under a constitutive HSP promoter and kanamycin resistance. M. avium 104 expressing CFP: pMSP12∷cfp under control of the msp12 promoter and kanamycin resistance (kindly provided by Christine Cosma and Lalita Ramakrishnan [19]). Mycobacteria were cultured in Middlebrook 7H9 medium (Difco/Becton Dickinson) supplemented with glycerol, Tween80 and ADC. Iron free 7H9 was made in acid-washed containers. Mycobacteria were quantified by plating on 7H10/OADC agar, luminescence (luciferase reporter assay) or flow cytometry.

Infection

In vitro infection. Mycobacteria were briefly sonicated in PBS and added to macrophages for 4 hours before washing off excess bacteria. Confocal microscopy experiments were performed 3-10 days after infection. Macrophages infected with GFP-expressing M. avium were analyzed with a Coulter flow cytometer, or by plating. Macrophages infected with luciferase-expressing M. avium were lysed and luminescence read in a Wallac 1420 VICTOR Luminometer (PerkinElmer). In vivo infection was done by injecting log phase mycobacteria (1-5×107 bacteria/mouse) in 0.5 ml PBS intraperitoneally. Bacterial load was measured by plating serial dilutions of organ (spleen, liver) homogenates or heparinised blood. Magnetic Dynabeads (Sheep-anti-rat, Dynal/Invitrogen) coated with the pan-leukocyte rat anti mouse CD45 Ab (BD) was used to separate leukocytes from plasma in aliquots of heparinised mouse blood. Leukocyte depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry and fractions were plated to compare bacterial loads

Lcn2 measurements

Mouse Lcn2 protein in serum or in cell supernatants was quantified by sandwich ELISA specific for Lcn2 as described [5]. The normal level of serum Lcn2 in mice was 20-100 ng/ml. Results are presented as means ± s.d. from triplicate measurements in one experiment unless otherwise stated.

Confocal imaging

Macrophages grown on coverslip-bottomed confocal dishes (Magtek) were stained and analyzed as described in [20]. Un-labeled, control-labeled and single-labeled samples were always included to set the right amplifications, adjusted to below saturation. The Imaris 6.0 software from Bitplane was used for the surface and volume renderings.

Electron microscopy

Day 5-7 BMDM from Lcn2-deficient mice were infected with M. avium luciferase for 5-7 days before addition of BSA gold particles (14 nm). After 1.5 hours uptake at 37°C, cell preparation and image uptake was performed as described in [21]

Statistical analysis

Overall differences in bacterial load between WT and Lcn2 KO mice were evaluated by a mixed method approach using SPSS software and a General Linear Model: A univariate analysis of the variance in bacterial loads from 3 separate experiments, each with 4-5 mice per group.

Results

Lcn2 limits the growth of M. avium in culture

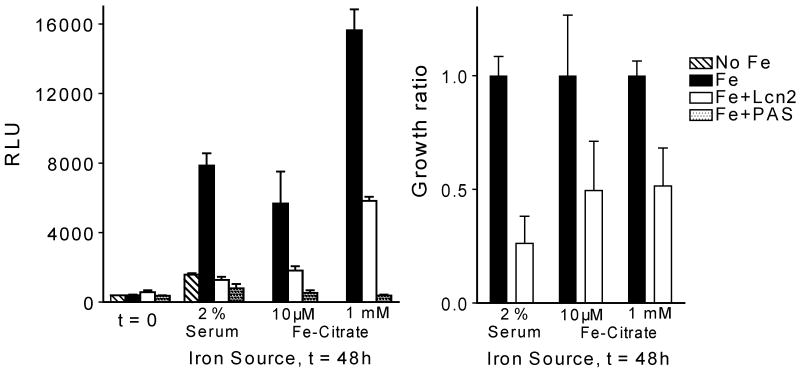

Lcn2 is bacteriostatic to susceptible strains of E. coli, cultured in vitro and during in vivo mouse infections, by sequestration of the siderophore enterochelin [5]. Lcn2 also binds to carboxymycobactins, soluble derivatives of the mycobactin siderophores [4, 22]. We found that Lcn2 suppressed the in vitro growth of M. avium with 50-80% in log-phase cultures (figure 1). Comparable growth-inhibition by Lcn2 was obtained with either serum transferrin (2% serum from Lcn2 KO mice) or ferric citrate at a low (10μM) and high (1mM) dose as the iron source. Our results are in accordance with the recent observation by Martineau et al. and Saiga et al. showing that Lcn2 inhibits the in vitro growth of M. tuberculosis [23, 24]. The drug p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) was more efficient than Lcn2 in growth suppression of M. avium (figure 1), possibly because Lcn2 only binds to a size-restricted subset of the carboxymycobactins [4] whereas PAS inhibits the synthesis of all carboxymycobactins, the cell wall-bound mycobactins, and may affect other pathways in the mycobacteria [25].

Figure 1.

Lcn2 suppresses growth of M. avium. Luciferase-expressing M. avium were grown in iron-free medium supplemented with serum (2 %) from Lcn2 KO mice or ferric-citrate (10 μM or 1 mM) as sources of iron, and Lcn2 (6 μg/ml) or p-aminosalicylic acid (PAS, 10 μg/ml). Growth was assessed by measuring luciferase activity in cell lysates (RLU). Data in the left panel are shown as mean RLU ± s.d. from one experiment. In the right panel the growth of M. avium in the presence of Lcn2 relative to growth in full-iron medium is shown as an average from repeated experiments.

M. avium and TLR ligands induce Lcn2 production

Mycobacteria primarily inhabit macrophages and we next checked if macrophages could produce Lcn2. In vitro-infected bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) stimulated with the MyD88-dependent repertoire of TLR-ligands [26] secreted Lcn2, whereas stimulation with double stranded RNA (i.e. poly(I:C)), a TRIF-dependent TLR3-mediated ligand, did not (figure 2A). Macrophages infected in vitro with virulent M. avium at various multiples of infection (MOI) secreted Lcn2 in a time- and dose-dependent manner (figure 2B). The M. avium-induced secretion was again dependent on MyD88 and not TRIF (figure 2C), in agreement with the data from figure 2A and a genome analysis suggesting the presence of NFκB but not IRF promoter sites upstream of the mouse Lcn2 gene. Lcn2 was not detected in Lcn2-deficient cells (figure 2C). This suggests that Lcn2 is an inflammation-driven acute phase protein induced through MyD88, most likely dependent on activation of NFκB [27, 28].

Figure 2.

Macrophages are induced to produce Lcn2. Day 7 mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were incubated with TLR-ligands (A) or infected with M. avium (B, C) and the supernatants assessed for Lcn2 by ELISA. (A) TLR-ligands (20 hours): 100 ng/ml Pam3CysSK4, 1 μg/ml LTA, 100 ng/ml FSL1, 20 μg/ml poly(I:C), 10 ng/ml LPS, 200 ng/ml flagellin, 5 μM R848, 5 μM CpG. (B) M. avium for indicated time and multiples of infection, MOI. (C) BMDM from WT, Lcn2 KO, MyD88 KO and TRIF KO infected with M. avium at MOIs as indicated for 4 days. All data are presented as means ± s.d. of triplicate measurements from one experiment repeated two (A) three (B) or one (C) times.

Lcn2 is endocytosed by macrophages and traffics to lysosomal compartments

For Lcn2 to impact the life of intracellular mycobacteria, macrophages should efficiently translocate Lcn2 to relevant compartments. We found that macrophages endocytosed Lcn2, promoting accumulation of Lcn2 as shown by flow-cytometry (figure 3A) and confocal microscopy (figure 3B). The initial localization (up to 30 min) of Lcn2 overlapped to a large extent with transferrin (figure 3B), suggesting clathrin-mediated uptake through early endosomes. Iron-loaded diferric transferrin bound to its receptor is sorted from early/sorting endosomes to recycling endosomes; empty or monoferric transferrin is then transported back to the surface for reuse [29, 30]. After 30 min, transferrin remained in the periphery of the macrophages whereas Lcn2 traveled deeper and often accumulated in perinuclear areas, coincident with the location of lysosomes in many macrophages (figure 3B). Lcn2 continuously co-localized with dextran, a fluid-phase marker of antigen-presenting compartments such as late endosomes and lysosomes. Moreover, Lcn2 was transported to compartments positive for lysotracker, a low-pH-specific marker of acidified lysosomes (figure 3B), and for the chaperone receptor-associated protein (RAP) that binds to members of the endocytic LDL receptor superfamily and is transported directly to lysosomes [31]. Thus, in uninfected macrophages, Lcn2 was initially endocytosed into early endosomes together with transferrin, but was subsequently sorted to lysosomes, separately from transferrin.

Figure 3.

Macrophages endocytose Lcn2. (A) Accumulation of Lcn2. Day 7 BMDM were incubated with 5 μg/ml Lcn2-A488 and left for indicated times before analysis by flow cytometry. Data are represented as flow histogram (left) or mean fluorescence index of all time points (right). (B) Lcn2 is transported to lysosomes. Day 7 BMDM were incubated with 5 μg/ml Lcn2-A647 together with 5 μg/ml transferrin-A546 (Tf), 1 μg/ml Dextran-A488 (Dex), or 5 μg/ml RAP-A488 (RAP) for indicated times, or with 25 nM Lysotracker green (Lyso) for the last 30 minutes before analysis with confocal microscopy. Scale bars are 10 μm.

Effect of Lcn2 on growth of M. avium in macrophages and in mice

To examine if Lcn2 could affect intracellular growth of mycobacteria, we infected primary mouse macrophages with M. avium. There was only a small and variable growth-inhibitory effect of Lcn2 on M. avium in peritoneal and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from Lcn2 KO mice and wild type littermate controls (figure 4A-C and figure S1), even when adding recombinant Lcn2 (figure 4D). The number of bacteria per macrophage, as seen in the confocal microscope, varied from undetectable levels to an estimated 50 bacteria per cell, possibly obscuring minor inhibitory effects of Lcn2.

Figure 4.

Effect of Lcn2 on M. avium growth in macrophages and in vivo in mice. BMDM from WT or Lcn2 KO mice were infected with (A) M. avium-luciferase for 4 days at MOI 3:1 and growth analyzed by luminescence (RLU), (B) M. avium-GFP for 4 days at MOI 3:1 and growth analyzed by FACS analysis (Mean Fluorescence Index), (C) M. avium for 4 days at MOI 3:1 and growth assayed by CFU. (D) Shows the effect of rLcn2 (8 μg/ml) on M. avium-luciferase growth in macrophages for 6 days. Data in (A-D) are shown as means ± s.d. from single experiments repeated two to ten times. Dose and kinetics from these experiments can be found in Supplementary figure S1. (E, F) WT and Lcn2-deficient mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 107 CFU M. avium for indicated times before blood, spleen and liver were collected from 4-5 mice per group. Results from one experiment are shown. (E) Serum Lcn2 as measured by ELISA. Black squares represent uninfected mice. White and grey boxes show Lcn2 levels with s.d. from groups of infected mice (n = 4-5). (F) Bacterial load in blood, spleen and liver. Combined p-values obtained from a univariate analysis of variance of three separate experiments were p = 0.1 and p = 0.05 for blood counts day 1 and 2 post infection, respectively. Combined p-values > 0.1 for blood counts day 4 and 8, and for all tissue counts (spleen, liver) at all time points. (G) Bacterial load in blood (black bars), CD45+ blood leukocytes (hatched bars), and leukocyte-depleted plasma (dotted bars) from Lcn2 KO and WT mice infected with M. avium, 1 day post infection. Recovery (open bars) represents the sum of CFUs from leukocyte and plasma fractions. Data are showed as means ± s.d. from 5 mice.

We next compared the growth of M. avium in Lcn2 knockout mice and wild-type littermate controls after intraperitoneal infection. Results from one experiment repeated three times are shown in figure 4E, F. The serum level of Lcn2 increased rapidly from a basal level of 20-100 ng/ml to about 1 μg/ml in infected mice (figure 4E), comparable to levels previously seen during acute infections with pathogenic E. coli [5]. There was a 2-10 fold elevated number of bacteria in the blood of Lcn2 KO mice compared to controls during the first two days post infection (figure 4F), suggesting that the high level of Lcn2 is protective only in early phases of infection. Combined p-values obtained from a univariate analysis of variance of three separate experiments were p = 0.1 for day 1, p = 0.05 for day 2 and p > 0.1 for blood counts day 4 and 8 post infection. After 3 weeks bacteria were absent from the blood and could only be found in tissues. Although a small increase in organ bacterial load (spleen and liver) was occasionally seen in Lcn2 knockouts the first day(s) post infection, Lcn2 showed no evident inhibition of mycobacterial growth in organ tissues (Fig 4F) with combined p-values > 0.1 for all time points. Lcn2 did not limit the growth of M. avium in any of the organs in late infections (up to 18 weeks, data not shown), altogether suggesting that intracellular mycobacteria were protected against Lcn2. By separating blood cells from plasma in day 1 infected mice we found a substantial fraction of the mycobacteria to be free in the plasma fraction (figure 4G). Thus, it is possible that elevated serum Lcn2 affect mycobacterial growth only in the extracellular phase.

Intracellular M. avium does not co-localize with Lcn2

A possible explanation for the limited effect of Lcn2 on intracellular growth of M. avium is lack of interaction between Lcn2 and the bacterium. In infected macrophages, M. avium clearly co-localized with transferrin and not with Lcn2 (figure 5A, B with 3D projection in Movie 1 (http://www.nt.ntnu.no/normic_movies/Halaas_Movie1.mov)). Lcn2 localized to areas adjacent to the mycobacteria, and overlapped with dextran, lysotracker and RAP, indicating that Lcn2 also traffics to acidified lysosomes in infected macrophages (figure 5A). 3D-modeling of z-stack images showed separation between the Lcn2-containing lysosomes and the mycobacteria, whereas transferrin was located to the mycobacteria (figure 5A and B). Live-cell imaging showed that there was occasional adherence of Lcn2-containing vesicles (Lcn2-A647, red) to mycobacteria (M. avium-GFP, green) without fusion of the two (http://www.nt.ntnu.no/normic_movies/Halaas_Movie2.mov). The juxtaposition of intracellular mycobacteria to lysosomes was also seen by electron microscopy (figure 5C). Endogenous Lcn2 also failed to co-localize with the mycobacterial phagosome (figure 5D). Thus, even though Lcn2 and transferrin were both efficiently endocytosed by infected macrophages, the resident mycobacteria co-localized with recycling transferrin and not with Lcn2 trafficking the lysosomal pathway.

Figure 5.

M. avium co-localize with transferrin but not Lcn2 or lysosomal markers. (A) Day 7 BMDM were infected for 4 days with M. avium-GFP or CFP and incubated for 2 hours with 5 μg/ml Lcn2-A647 together with 5 μg/ml transferrin-A546, 1 μg/ml dextran-A488, 5 μg/ml RAP-A488 or 25 nM Lysotracker green (only included the last 30 minutes). Scale bars are 10 μm. (B) Surface rendering model created from the 3D (z-stack) images in the upper panel of (A) of the macrophage infected with M. avium (green) given Lcn2 (red) and transferrin (blue). Scale bar is 5 μm. (C) Transmission electron microscopy picture of day 7 BMDM infected with M. avium and pulsed with BSA gold particles for 1.5 hours. Gold particles were mainly found accumulated in presumably lysosomal compartments (Ly) that were in close proximity to the bacteria (asterisks). (D) Day 7 BMDM infected with M. avium-GFP were labeled with anti-Lcn2 Abs. Scale bar is 10 μm.

M. avium intersects the Rab11+ endocytic recycling compartment

Rab proteins are small GTPases that control the identity, integrity and trafficking of intracellular organelles, membranes and proteins [32, 33]. In general, Rab5 regulates transport into early/sorting endosomes (EE) and EE homotypic fusion. From the EE, receptors and cargo can follow three alternative pathways; Rab7 regulates exit and transport to late endosomes and lysosomes, Rab4 contributes to rapid recycling to the surface, and Rab11 is involved in slow recycling through the endosomal recycling compartments (ERC) to the surface [30, 32-34]. Virulent and metabolically active Mycobacterium spp. are believed to arrest phagosome maturation somewhere along the phagolysosomal pathway before the Rab5 to Rab7 conversion [8, 9, 12, 35, 36]. We found that Lcn2 and transferrin co-localized early after endocytosis before Lcn2 was trafficked down the lysosomal pathway. However, since Lcn2 endocytic vesicles did not cross with the mycobacteria, we speculated that the mycobacteria were in the transferrin recycling pathway and not in the lysosomal pathway. Indeed we found a high degree of Rab11 overlapping with the intracellular mycobacteria in established infections (figure 6A). The co-localization was more pronounced with the Rab11a isoform than with Rab11b. The co-localization of mycobacteria with Rab5a was mostly absent (figure 6A), but occasional accumulation of Rab4a and transferrin receptor adjacent to the mycobacteria was seen (figure 6A). In agreement with literature, we did not find Rab7 associated with the mycobacterial phagosome (data not shown). Although Rab4 is mostly implicated in the rapid recycling pathway, it also participates in recycling from the ERC [30, 32-34]. High resolution 3D imaging and computer assisted surface rendering and analysis further revealed that there was significant co-localization between the mycobacteria and Rab11a (figure 6B), as shown in the co-localization channel (right image). This suggests either that mycobacteria acquire Rab11a positive vesicles or that mycobacteria share membranes with the recycling Rab11a compartment. We suggest a model where M. avium inhabit the transferrin and Rab11+ endocytic recycling compartments, avoiding Lcn2 trafficking the bactericidal lysosomal pathway (figure 6C).

Figure 6.

M. avium interact with the Rab11 recycling compartment. (A) BMDM infected for 4 days with M. avium-CFP were labeled with anti-Rab11a, anti-Rab11b, anti-Rab4a, anti-Rab5a or anti-transferrin receptor Abs. Upper panel shows an overview (scale bar 10 μm), lower panel the indicated close-up shots. (B) A 3D z-stack of an infected Rab11a-labeled macrophage is shown as a top-down slice, a 3D surface rendering model and the 3D co-localization-channel of M. avium and Rab11a with the view-point indicated in the left panel showing direct overlap between Rab11a-compartments and mycobacteria. Scale bar is 10 μm. (C) Our model suggesting that M. avium locates with the Rab11+ endocytic recycling compartment, thereby obtaining transferrin while avoiding Lcn2 and other endocytosed substances that traffic to lysosomes for degradation.

Discussion

Mycobacteria constitute a major global health problem and there is an intense effort to understand the biology of the host-pathogen interactions and immunity against mycobacteria. In particular, the contribution of innate immunity is not clear [37]. Here we show that the innate immunity protein Lcn2 may contribute in early defense against Mycobacterium avium, likely by scavenging of carboxymycobactin siderophores [4]. However, Lcn2 was only effective against free-living M. avium in culture or in the mouse bloodstream during the early phase of infection where we found a substantial fraction of the bacteria to be extracellular. In this innate phase of infection, neutrophils are central as they release premade antimicrobial factors, including Lcn2 [38, 39], and clear pathogens through phagocytosis and intracellular killing. The increased systemic levels of Lcn2 together with circulating neutrophils could thus limit the severity of acute disease. Our data find support in a recent paper demonstrating that neutrophils make a significant contribution in limiting in vitro growth of M. tuberculosis in blood, and that blood neutrophil counts are inversely related to risk of infection [23]. It is plausible that Lcn2 would impart a similar effect on mycobacteria entering through mucosal surfaces, since epithelial cells lining the respiratory and gastrointestinal epithelium secrete Lcn2 and may lower the size of the inoculum or prevent invasion [5, 39].

Many immune effector mechanisms are met with evasion strategies by bacteria. To avoid humoral effectors, mycobacteria take residence within tissue macrophages where they block phagolysosomal maturation [7-10]. There was little effect of Lcn2 on mycobacteria grown inside macrophages in vitro as well as in established in vivo infections, when the mycobacteria presumably also inhabit macrophages. Recently a study was published showing that Lcn2 deficient mice were impaired in resistance to M. tuberculosis infection [24]. In accordance with our results, the authors found that the natural host cells, macrophages, did not depend on Lcn2 to combat mycobacterial infection. Instead, the authors showed that alveolar epithelial cells deficient in Lcn2 became host cells for mycobacteria. We corroborate the insufficiency of Lcn2 in restricting mycobacterial growth in macrophages and provide an explanation by showing that M. avium diverges from the endolysosomal pathway. The difference in in vivo susceptibility between our studies may stem from different infection routes (intraperitoneal versus intratracheal) and/or different mycobacterial strains.

Lcn2 co-localized with transferrin shortly after endocytosis, but diverged from transferrin at later time points, showing instead preferred localization to lysosomes. We found very little association between endocytosed or endogenous Lcn2 and mycobacteria in the macrophage, opposed to what would be expected if the arrested phagosome was in the lysosomal pathway receiving cargo (including Lcn2) from early endosomes. Transferrin was, however, always found in the mycobacterial vacuoles [11]. We thus hypothesized that the mycobacteria resided in a compartment outside of the phagolysosomal pathway, avoiding Lcn2 but retaining access to transferrin. The co-localization of M. avium with Rab11 supported this hypothesis. Mycobacteria are generally believed to arrest phagosome maturation at a level between early endosomes (since they accumulate Rab5) and late endosomes (as they are negative for Rab7) [8, 9, 36] whereas transferrin traffics the slow Rab11 endosomal recycling pathway from early/sorting endosomes (Rab5) to endocytic recycling compartment (Rab11) and back to the surface [30, 32-34, 40]. The high degree of overlap between Rab11 and M. avium suggests that M. avium may retrieve transferrin-iron through physical interaction with the recycling pathway [29]. The divalent metallic ion pump DMT1 is also associated with transferrin receptor in the recycling pathway, possibly aiding in iron delivery [41]. We cannot, however, rule out that iron is pumped out into the cytosol before being transported back to the mycobacteria. The location of M. avium in the recycling pathway also explains why Lcn2, trafficking by the lysosomal pathway, did not limit growth of intracellular mycobacteria. These observations add new aspects to the biology of Mycobacterium-macrophage interaction and the immune evasion strategy of an intracellular life.

Metabolically active and virulent mycobacteria (M. tuberculosis, M. avium, M. bovis) all retain Rab5 on their phagosome to facilitate fusion with early endosomes and access to transferrin iron [8, 9, 36]. We did not observe co-localization of Rab5a with M. avium in our study, despite overlap between the mycobacteria and transferrin or the transferrin receptor. In the study by Kelley and Schorey [9], overexpression of dominant-negative Rab5 (GDP-Rab5) resulted in progression of the M. avium phagosome towards lysosomes and increased bacterial killing. However, as the authors also pointed out, the phagosomal maturation was probably triggered by iron deficiency due to decreased uptake of transferrin as Rab5 is essential in transferrin receptor endocytosis [42], and not necessarily that Rab5 needs to be present on the mycobacterial compartment to ensure phagosomal maturation arrest.

In summary, this study provides intriguing findings relevant to mycobacterial immune reactions and novel aspects to immune evasion mechanisms employed by intracellular mycobacteria. First, Lcn2 restricted the growth of Mycobacterium avium in the blood of infected mice, pointing to the importance of innate immunity functions targeting iron-acquisition in the immediate defense against mycobacteria. Secondly, during the intracellular stage, mycobacteria seem to reside in the recycling pathway, thus efficiently avoiding Lcn2-mediated immunity while retaining access to transferrin. Whether this applies to other pathogenic mycobacteria is currently under investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Karen Nykkelmo for help with the mouse infections and Stian Lydersen for help with statistics.

Financial support: Research council of Norway (grant 164050/S30 to THF, 179350/S50 to ØH) and NIH (grant R01 AI59432 to RKS)

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: none

Presented in part: 2009 Keystone Symposium on Tuberculosis: Biology, Pathology and Therapy, Keystone, CO. 2008 IEIIS Meeting, Edinburgh, Scotland. 2008 Keystone Symposium on Innate immunity, Keystone, CO

References

- 1.Schaible UE, Kaufmann SH. Iron and microbial infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:946–953. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratledge C, Dover LG. Iron metabolism in pathogenic bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:881–941. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. The neutrophil lipocalin NGAL is a bacteriostatic agent that interferes with siderophore-mediated iron acquisition. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1033–1043. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes MA, Paulsene W, Jide X, Ratledge C, Strong RK. Siderocalin (Lcn 2) also binds carboxymycobactins, potentially defending against mycobacterial infections through iron sequestration. Structure. 2005;13:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, et al. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turenne CY, Wallace R, Jr, Behr MA. Mycobacterium avium in the postgenomic era. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:205–229. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philips JA. Mycobacterial manipulation of vacuolar sorting. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2408–2415. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Via LE, Deretic D, Ulmer RJ, Hibler NS, Huber LA, Deretic V. Arrest of mycobacterial phagosome maturation is caused by a block in vesicle fusion between stages controlled by rab5 and rab7. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13326–13331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelley VA, Schorey JS. Mycobacterium's arrest of phagosome maturation in macrophages requires Rab5 activity and accessibility to iron. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3366–3377. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-12-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemens DL, Horwitz MA. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome and evidence that phagosomal maturation is inhibited. J Exp Med. 1995;181:257–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemens DL, Horwitz MA. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome interacts with early endosomes and is accessible to exogenously administered transferrin. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1349–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schaible UE, Russell DG. Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes are accessible to early endosomes and reflect a transitional state in normal phagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6960–6968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gobin J, Horwitz MA. Exochelins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis remove iron from human iron-binding proteins and donate iron to mycobactins in the M. tuberculosis cell wall. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1527–1532. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo M, Fadeev EA, Groves JT. Mycobactin-mediated iron acquisition within macrophages. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:149–153. doi: 10.1038/nchembio717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olakanmi O, Schlesinger LS, Ahmed A, Britigan BE. Intraphagosomal Mycobacterium tuberculosis acquires iron from both extracellular transferrin and intracellular iron pools. Impact of interferon-gamma and hemochromatosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49727–49734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Voss JJ, Rutter K, Schroeder BG, Su H, Zhu Y, Barry CE., III The salicylate-derived mycobactin siderophores of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are essential for growth in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1252–1257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratledge C. Iron, mycobacteria and tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2004;84:110–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan Y, Crane DD, Simpson RM, et al. The 16-kDa alpha-crystallin (Acr) protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is required for growth in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9578–9583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cosma CL, Humbert O, Ramakrishnan L. Superinfecting mycobacteria home to established tuberculous granulomas. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:828–835. doi: 10.1038/ni1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halaas O, Husebye H, Espevik T. The journey of Toll-like receptors in the cell. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;598:35–48. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-71767-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuffers S, Sem Wegner C, Stenmark H, Brech A. Multivesicular endosome biogenesis in the absence of ESCRTs. Traffic. 2009;10:925–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snow GA. Mycobactins: iron-chelating growth factors from mycobacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1970;34:99–125. doi: 10.1128/br.34.2.99-125.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martineau AR, Newton SM, Wilkinson KA, et al. Neutrophil-mediated innate immune resistance to mycobacteria. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1988–1994. doi: 10.1172/JCI31097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saiga H, Nishimura J, Kuwata H, et al. Lipocalin 2-dependent inhibition of mycobacterial growth in alveolar epithelium. J Immunol. 2008;181:8521–8527. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown KA, Ratledge C. The effect of p-aminosalicyclic acid on iron transport and assimilation in mycobacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;385:207–220. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(75)90349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bu DX, Hemdahl AL, Gabrielsen A, et al. Induction of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in vascular injury via activation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:2245–2253. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowland JB, Sorensen OE, Sehested M, Borregaard N. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin is up-regulated in human epithelial cells by IL-1 beta, but not by TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2003;171:6630–6639. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byrne SL, Mason AB. Human serum transferrin: a tale of two lobes. Urea gel and steady state fluorescence analysis of recombinant transferrins as a function of pH, time, and the soluble portion of the transferrin receptor. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2009;14:771–81. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0491-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant BD, Donaldson JG. Pathways and mechanisms of endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:597–608. doi: 10.1038/nrm2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Czekay RP, Orlando RA, Woodward L, Lundstrom M, Farquhar MG. Endocytic trafficking of megalin/RAP complexes: dissociation of the complexes in late endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:517–532. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.3.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz SL, Cao C, Pylypenko O, Rak A, Wandinger-Ness A. Rab GTPases at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3905–3910. doi: 10.1242/jcs.015909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonnichsen B, de RS, Nielsen E, Rietdorf J, Zerial M. Distinct membrane domains on endosomes in the recycling pathway visualized by multicolor imaging of Rab4, Rab5, and Rab11. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:901–914. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee BY, Clemens DL, Horwitz MA. The metabolic activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, assessed by use of a novel inducible GFP expression system, correlates with its capacity to inhibit phagosomal maturation and acidification in human macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:1047–1060. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clemens DL, Lee BY, Horwitz MA. Deviant expression of Rab5 on phagosomes containing the intracellular pathogens Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Legionella pneumophila is associated with altered phagosomal fate. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2671–2684. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2671-2684.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korbel DS, Schneider BE, Schaible UE. Innate immunity in tuberculosis: myths and truth. Microbes Infect. 2008;10:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kjeldsen L, Bainton DF, Sengelov H, Borregaard N. Identification of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin as a novel matrix protein of specific granules in human neutrophils. Blood. 1994;83:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kjeldsen L, Cowland JB, Borregaard N. Human neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and homologous proteins in rat and mouse. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:272–283. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(00)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trischler M, Stoorvogel W, Ullrich O. Biochemical analysis of distinct Rab5- and Rab11-positive endosomes along the transferrin pathway. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 24):4773–4783. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lam-Yuk-Tseung S, Gros P. Distinct targeting and recycling properties of two isoforms of the iron transporter DMT1 (NRAMP2, Slc11A2) Biochemistry. 2006;45:2294–301. doi: 10.1021/bi052307m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stenmark H, Parton RG, Steele-Mortimer O, Lutcke A, Gruenberg J, Zerial M. Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J. 1994;13:1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.