SYNOPSIS

The role of the American Red Cross in the U.S. response to the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic holds important lessons for current-day pandemic response. This article, which examines local ARC responses in Boston, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Richmond, Virginia, demonstrates how the ARC coordinated nursing for military and civilian cases; produced and procured medical supplies and food; transported patients, health workers, and bodies; and aided influenza victims' families. But the organization's effectiveness varied widely among localities. These findings illustrate the persistently local character of pandemic response, and demonstrate the importance of close, timely, and sustained coordination among local and state public health authorities and voluntary organizations before and during public health emergencies. They further illustrate the persistently local character of these emergencies, while underscoring the centrality and limits of voluntarism in American public health.

On October 1, 1918, when U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue decided the nationwide outbreak of severe influenza warranted a national response, he telegraphed the American Red Cross (ARC) national headquarters in Washington, D.C. The message requested that the organization “assume charge of supplying all the needed nursing personnel” to combat the pandemic, and that it “furnish emergency supplies” when local authorities could not do so promptly enough. The Surgeon General asked that the ARC pay the nurses' salaries and expenses, and expend $575,000 to finance the effort.1

This request would later prove quite burdensome, given that pandemic influenza sickened about 25 million Americans and caused at least 550,000 excess deaths in 1918–1919. But the ARC did more than comply with the Surgeon General. Through its capillary network of divisions and local chapters, the organization provided more than $2 million in equipment and supplies to hospitals; established kitchens to feed influenza sufferers and houses for convalescence; transported people, bodies, and supplies; and recruited more than 18,000 nurses and volunteers to serve alongside U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) workers and local health authorities. The ARC also distributed PHS pamphlets and circulars on prevention and care of influenza, and directed its chapters to form influenza committees to work with local health authorities and regional ARC divisions.2–7

While American society has changed much in the past nine decades, the ARC and other voluntary organizations still provide substantial aid in public health emergencies, while local health departments and physicians remain the first responders in pandemics. An examination of the ARC's role in the 1918 pandemic, therefore, can inform these continuing interactions between voluntary bodies and public health authorities.8,9

Because the ARC response to the 1918 influenza pandemic occurred primarily on the local level, this article focuses on case studies of selected cities: Boston, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Richmond, Virginia. These cities were chosen as an illustrative and geographically varied sample. Boston was selected primarily because it was the first U.S. city to encounter pandemic influenza, St. Louis because it was later praised as the “model city” for influenza response due to its low death rates, Pittsburgh because it experienced one of the highest influenza death rates of any major city, and Richmond due to its location in the culturally distinct region of the South. Table 1 offers a comparison of the cities and ARC chapters in 1918.2,10

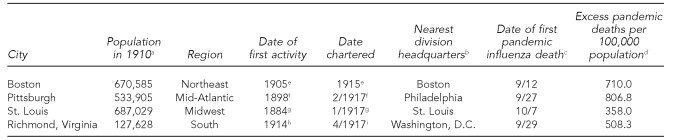

Table 1.

Characteristics of Red Cross chapters in study cities, 1918–1919

aGibson C. Population of the 100 largest urban places: 1910. Population division working paper no. 27 [cited 2010 Mar 5]. Washington: Bureau of the Census (US); 1998. Available from: URL: http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0027/twps0027.html

bRed Cross War Council. The work of the American Red Cross during the war: a statement of finances and accomplishments for the period Jul. 1, 1917 to Feb. 28, 1919. Washington: American Red Cross; 1919.

cCrosby AW. America's forgotten pandemic: the influenza of 1918. Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press; 1989.

dMarkel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA, Sloan A, Michalsen J, Stern A, et al. Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by U.S. cities during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA 2007;298;644-54.

eAmerican Red Cross of Massachusetts Bay. Our chapter. History of the American Red Cross of Massachusetts Bay [cited 2009 Nov 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.bostonredcross.org/general.asp?SN=4038&OP=4039&IDCapitulo=29RRV668X1

fAmerican Red Cross, Pittsburgh chapter. A history of the activities of the chapter from its organization to January 1, 1921. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Co.; 1922.

gAmerican Red Cross, St. Louis area chapter. History [cited 2009 Nov 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.redcrossstl.org/AboutUs/MissionHistory.aspx

hJenkinson C. The organization of new chapters. Red Cross Magazine 1914;2:99.

iAmerican Red Cross, Richmond, Virginia, chapter. The first fifty years: Richmond, Virginia, chapter, American Red Cross, 1917–1967. Richmond, (VA): American Red Cross; 1967.

This granular portrait of the ARC's response to the pandemic indicates that the organization's impact varied considerably among different localities. While in some cities the ARC functioned as a critical component of the public health infrastructure, in others it acted as merely one among many voluntary bodies providing assistance during the crisis. The case studies, though occurring in the World War I era, suggest several lessons for public health authorities and voluntary groups involved in pandemic response today: (1) voluntary bodies must be well integrated into pandemic preparedness and response plans at all levels, (2) advance discussions among volunteer groups and public health authorities can improve utilization of volunteer resources during crises, and (3) voluntary groups can assist meaningfully in nationwide distribution of pandemic preparedness information.

THE AMERICAN RED CROSS IN 1918

To understand why the ARC played such a major role in responding to the influenza pandemic, it is necessary to contextualize its mission within the American voluntarist tradition. In the 19th-century U.S., the lack of a strong centralized state resulted in the proliferation of associations, from fire brigades to missionary societies, to address the needs and interests of the populace. In 1881, Clara Barton adapted the principles of the Geneva-based Red Cross movement, which had focused on formation of neutral, volunteer wartime medical auxiliaries in Europe, to reflect the American tradition of associations that met the immediate needs of citizens. She stipulated that the new ARC would provide, in addition to wartime medical aid, assistance following “national calamities” such as “plagues, cholera, yellow fever and the like, [or] devastating fires or floods.” In 1900, Barton secured a Congressional charter for the organization, which made it directly accountable to Congress (though still privately funded), and designated it as not only the organization responsible for carrying out the U.S. government's obligations under the Geneva conventions, but the official U.S. disaster relief organization. Congress has rewritten this charter several times, but the ARC retains a unique quasi-governmental status.11–14

In the early 1900s, ARC chapters were formed in major U.S. cities. The organization's national leaders also raised an endowment; launched nursing, first aid, and home hygiene divisions; and built a monumental headquarters in Washington. Though political and military leaders served on the ARC governing committee, volunteer philanthropists and professional executives functioned as the organization's de facto leaders during these years.15,16

When the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, however, President Woodrow Wilson immediately assembled a War Council of business and government leaders to take charge of the ARC. Wilson's action, though violating the ARC charter's provisions for organizational governance, echoed his strategy of instituting temporary government control of railroads and agriculture to mobilize resources necessary to win the war. The War Council quickly revamped the organization. By 1918, the ARC had grown into a sprawling enterprise with 14 regional divisions, 3,684 chapters, 12,700 staff, and more than 20 million members. This expansion was enabled by wartime fundraising drives that netted $400 million (more than $5.7 billion in 2008 dollars).16–21

The largest force behind the wartime growth of the ARC, however, was its army of eight million female volunteers. During the war, these women produced 371 million “relief articles”—surgical dressings; hospital garments and supplies; sweaters, hats, and other knitted items for soldiers and sailors; and clothing for refugees. Others performed social work by assisting families of servicemen with their problems, working at refreshment canteens for mobilized servicemen, or joining the women's motor corps, which transported servicemen and doctors.3

Women's voluntary work had by this time become well entrenched in American culture. Nineteenth-century female benevolent societies, rooted in a gender ideology characterizing women as the moral guardians of the family and, by extension, the community, had allowed women from the middle and upper classes to move from the confines of the domestic sphere into the public sphere as moral reformers. The early 20th-century Progressive movement, which sought to create a more well-ordered society, transformed the mission of female voluntarism from moral reform to “municipal housekeeping.” Progressive women campaigned to clean up corrupt and squalid industrial cities and “improve” the conditions of the urban poor while campaigning for the vote to reform the political sphere.22–25

While some Progressive women opposed the war, by 1917 many had accepted wartime propaganda characterizing the conflict as a Progressive “war to end all wars,” and joined the ARC or other groups. Those less eager to join were pressured to do so by a deafening chorus of patriotic voices, from President Wilson's call for “a nation which has volunteered in mass,” to ARC propaganda, which framed volunteer service as an obligation of citizenship and advertised the organization as “The Greatest Mother” for wounded and homesick servicemen.26

This female volunteer army drew its recruits primarily from middle- and upper-class white women with leisure time. Many African American women were rebuffed by ARC chapters when they sought to participate, and had to create their own alternatives for wartime voluntarism. Similarly, black women seeking to enroll as ARC nurses met with frustration. During the war, the ARC served as the official recruiter of nurses for the U.S. Armed Forces. The nursing division, which required every ARC nurse to have completed three years of training in an accredited nursing school, enrolled 24,000 trained nurses. Trained black nurses, however, were rejected for service abroad, and were only enrolled as reserve members of the home defense program.7,15,27,28

These reserve home defense nurses proved indispensable in the influenza pandemic. In December 1918, the ARC sent black nurses, along with other formerly disqualified nurses such as married women, to care for servicemen in influenza-ridden military camps. The leaders of the nursing division, white hospital-trained nurses who had served as the gatekeepers of ARC nursing and the profession, had little choice during the pandemic but to accept black nurses, as well as less-trained nurses, into their ranks: the dimensions of the crisis simply forced them to temporarily abandon their rigid and discriminatory professional standards.7,28,29

BOSTON: VANGUARD CHAPTER

As influenza struck first in Boston, the city's Red Cross chapter became the first to mount a response to the pandemic. Cases had begun appearing among sailors in Boston Harbor in mid-August 1918, and by early September, the Boston chapter began providing nurses to military and civilian hospitals as well as charitable institutions. But with so many nurses serving in the war abroad, an acute nursing shortage soon developed. Consequently, military authorities asked the Red Cross to accept any volunteers who had completed the Red Cross course in home hygiene and possessed 72 hours of hospital experience. “The thirty who responded for immediate service were assigned to an open-air hospital where they worked for nearly a month in all kinds of weather,” the chapter later reported. The New England division then recruited 500 trained nurses from the Northeast U.S. and Canada to work throughout New England, and secured promises from local public health authorities to cover the nurses' salaries.30–32

Under an agreement with ARC headquarters established immediately after the Surgeon General's telegram, the PHS was to control placement of trained nurses the ARC recruited. But the New England division had already begun allocating nurses itself, in response to requests from local health authorities. Writing to national headquarters on October 4, division Manager James Jackson defensively explained this practice: “The division office has not provided nurses and supplies at the request of the Public Health authorities as the Public Health authorities have not been on the job.” The early onset of influenza in Boston, and subsequent frustration with the PHS, had led Boston ARC officials to ignore national headquarters' directives.4,32

The Boston chapter meanwhile redirected its volunteers from war work into influenza-related duties. The canteen unit, which had provided snacks, cigarettes, magazines, and good cheer to servicemen at train depots, now met the arriving nurse recruits at the stations with “proper food” to ensure that these scarce recruits would know they were welcome and needed. Volunteers who had been producing surgical dressings for servicemen switched to making gauze masks to protect those caring for influenza patients. Working for 17 days in a row, 537 volunteers produced 83,606 masks, which motor corps volunteers then delivered to hospitals, local organizations, and individual homes. The motor corps also transported items produced by the 484 volunteers in the sewing department, including 8,000 convalescent gowns, 500 pairs of pajamas, 100 nightgowns, and 40 sweaters for a children's hospital, as well as 70 flannel helmets, 70 pairs of hospital socks, 30 sheets and pillowcases, and 40 “thin convalescent robes and surgical shirts.” Additionally, the motor corps delivered meals to sick people at their homes, and provided 35 cars per day to transport nurses on visits to the sick. Other volunteers served in Red Cross dispensaries and diet kitchens throughout the city and neighboring towns. In the town of Needham, Massachusetts, for example, Red Cross volunteers set up a kitchen that provided 1,150 meals to the sick and 72 meals to nurses over a 12-day period.30

The Boston chapter and New England division also conducted a public health education and prevention campaign. Chapter staff members who had performed social outreach to the families of servicemen now sent out letters on influenza prevention to these families. The division also produced and distributed its own circulars on influenza. In early October, when national headquarters informed Jackson that it would be sending him copies of a PHS influenza prevention pamphlet, he responded curtly that no more circulars needed to be distributed, as the local peak of the pandemic had passed.30,32

When influenza abated in mid-October, Boston Red Cross workers reported that the pandemic had left “a good deal of social wreckage” including orphans, motherless children, and people with chronic health conditions. To ascertain the needs of this population, the chapter sent out workers to survey families referred by local nursing associations. Chapter leaders then sought advice from division and national headquarters about whether to divert resources from families of servicemen to families of civilian influenza victims. The ARC had long performed emergency social work with disaster victims, seeking to restore the “comforts” of home or find them temporary work. But W. Frank Persons, chairman of the ARC's influenza committee, suspected that providing long-term assistance to families affected by influenza could prove a bottomless or redundant task. Persons, who had previously worked at New York's Charity Organization Society, aiding the city's poor and disabled, told division directors that they should become involved only if “notified of serious social problems resulting from the epidemic which other existing agencies appear unable to meet.” In these cases, the organization agreed to pay salaries of those “experts in medical social service, child welfare and family rehabilitation” who visited the families. By March 1919, however, amid reports of families left in “poverty and acute distress” by influenza, as well as a declining caseload of servicemen's families due to the armistice, national headquarters increasingly permitted chapters to assist these people (Figure 1).30,33–38

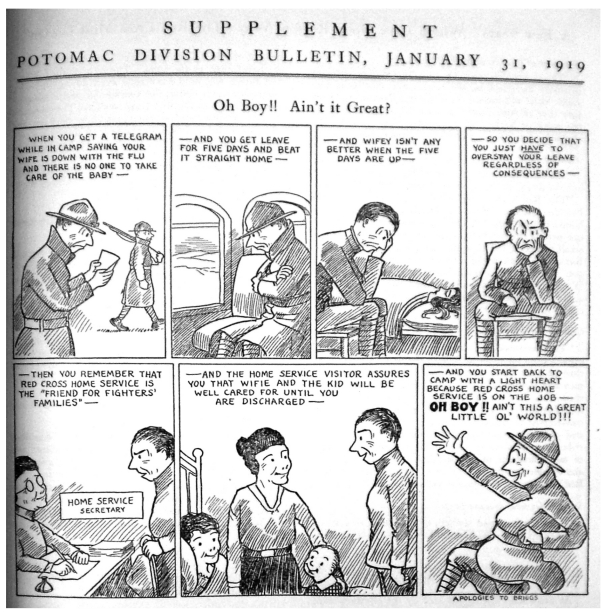

Figure 1.

Cartoon illustrating American Red Cross home service section social work with servicemen's families during the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919

Source: American Red Cross. Potomac Division bulletin, illustrated supplement. 1919 Jan 31. Box 520, Record Group 200, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Forced to act before national response to influenza was organized, the Boston chapter had coordinated its activities with local and state health authorities to meet the influenza crisis. It then later continued to ignore national headquarters and act on its own. In the long aftermath of the flu, the Boston chapter consulted with national leaders. But it responded primarily to local needs, not national directives—a pattern subsequently followed by other ARC chapters.

PITTSBURGH'S ROGUE RESPONSE

While the Boston chapter had improvised its influenza response, the Pittsburgh chapter was able to carefully plan its activities, as influenza did not arrive in the city until September 30. The chapter influenza committee drafted a plan to collect and distribute hospital supplies, ensure fair prices and adequate distribution of drugs and vaccines, recruit and allocate nurses, provide transportation through its motor corps, and procure caskets and gravediggers. The Pittsburgh chapter also organized five traveling dispensaries, equipping cars with “sickroom supplies, bedding and medicines,” and providing two nurses. (The state's health department provided a physician and three additional nurses for each dispensary.) Moreover, chapter case workers coordinated care for influenza patients in the city and the surrounding towns of Allegheny County. To coordinate chapter activities with those of the city health department, the chairman of the Red Cross influenza committee and medical representatives attended the health department's daily meeting on the pandemic. The Pittsburgh chapter thus operated as an effective complement to local health authorities. Nevertheless, its vigorous advocacy on behalf of local needs later drew ire from national headquarters.39–42

Exemplary of the chapter's work was how it sought to avoid the gruesome situations that had prevailed in other cities by ensuring an adequate supply of caskets and gravediggers. By October 14 in Philadelphia, hundreds of corpses had remained unburied for more than a week due to a shortage of coffins and gravediggers, with some cemeteries reportedly asking families to bury their own dead. “In view of [Philadelphia's] harrowing experience,” the Pittsburgh chapter asked the city's leading undertaker to survey burial conditions, and secured a promise from the Pittsburgh-based National Casket Company to “confine” its shipments to Allegheny County. The committee requisitioned “upholsterers, carpenters, varnishers, etc.,” for the company so it could increase casket production; arranged for the railroads “to expedite the shipment of caskets” from elsewhere; and requisitioned workers from local street cleaning departments to dig graves. The chapter also lent its ambulance and trucks to the city for transportation of bodies. As a result, “so far as we know there was no complaint, therefore, as to the delay in burying bodies,” the chapter reported.41,43

The chapter likewise sought to ensure adequate hospital supplies, drugs, and vaccines for Pittsburgh. It made wholesale procurement arrangements with local medical supply firms and druggists, used more than $54,000 collected for the war effort to buy from manufacturers “the entire output of cots and mattresses,” and requested a firm furnishing “bedpans, thermometers, urinals, hot water bottles, etc.” to “lay in all the supplies possible, and confine its shipments to Allegheny County.” When an influenza vaccine (later proved worthless) became available, the chapter arranged with one Pittsburgh druggist to handle all vaccine shipments and supply vaccine “at a fixed margin of 5% over cost that there might be no profiteering.” As in Boston, volunteers made gauze face masks to distribute to hospital workers. Finally, the chapter secured from division headquarters in Philadelphia supplies of sheets, blankets, and pillows.41,44,45

In distributing drugs and supplies, the chapter observed a clear hierarchy of priorities. Military hospitals and camps were to receive first priority, followed by coal plants and war production plants. Civilians' needs came last. Face mask requests received special scrutiny, with an order clerk determining “whether they are required in a quantity and whether actually necessary.” The chapter's prioritization in distribution indicated that even during the pandemic, it considered its primary mission to be aiding the war effort.46

As in Boston, the chapter took charge of recruiting nurses. Working with the city health department and hospital superintendents, a chapter nursing committee organized the emergency visiting nursing service for the city. The chapter advertised for recruits in local papers, “urging persons to give up nurses not indispensable” and inviting “those willing to help in any way to volunteer.” The chapter sent 70 graduate nurses, 40 practical nurses, and 172 aides and helpers to emergency hospitals throughout Allegheny County, to care for nearly 3,000 patients. These workers also cared for 12,000 home-bound cases, according to chapter estimates, and served at neighborhood medical relief stations the chapter established in vacated school buildings.41,42,47

One of the chapter volunteers' most important tasks was to navigate the city's network of charity agencies to obtain emergency care for needy influenza patients. In one case, when a “transient” came to the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) building “quite ill,” a YMCA worker phoned the chapter, which then secured him a bed at Allegheny General Hospital. The hospital had no ambulance to send to the YMCA, but “a friend from the influenza committee” stepped forward to buy his taxi fare “and eight minutes from the time [the YMCA] called, the young man was being placed in bed at a hospital ready to receive him,” a committee report stated. Another chapter task included working with townships in Allegheny County to establish local systems for emergency patient care. After the chapter worker supervised the outfitting of public buildings as emergency hospitals, they were placed under the care of a physician from the state's department of health. “A thorough-going and consistent cooperation … existed between the State Department of Health and the Red Cross” in this area, the chapter reported.42,48,49

The Pittsburgh chapter's many-faceted response to influenza seems a model of organized voluntarism. But ARC national headquarters later criticized chapter leaders for “thinking in terms of Pittssburgh [sic.] only” and making “it difficult for nearby small towns to handle their influenza situations. Supplies, caskets, nurses, etc., were not allowed to leave Pittsburgh on the pleas that Pittsburgh needed them more than the outlying communities.” ARC headquarters even blocked publication of a monograph on the chapter's work, thinking it “unwise to publish a statement showing such an attitude on the part of a large city toward its surrounding territory.”50

When the Pittsburgh chapter's activities are compared with the other chapters under study, national headquarters' criticism seems somewhat valid. None of the other chapters sought to confine scarce supplies within their localities. But this may be because the Boston and St. Louis chapters, unlike the Pittsburgh chapter, had close connections with nearby regional division offices. In Pittsburgh, the greater distance from regional headquarters permitted local chauvinism to flourish.

ST. LOUIS: MODEL CHAPTER IN A “MODEL INFLUENZA” CITY

When influenza reached St. Louis, the local ARC chapter stood at the vanguard of the response. On October 4, after receiving a copy of Surgeon General Blue's plea for Red Cross aid, the St. Louis chapter chairwoman, Virginia C. Hammar, requested a meeting with the city's health commissioner, Max Starkloff. Starkloff sent an assistant health commissioner to meet with her. Accompanied by the manager of the St. Louis-based Southwestern division, Hammar “tried to impress him with the importance of the impending epidemic,” according to a chapter report.51

Starkloff had been tracking the flu since it had spread beyond Boston. In late September, the first case had appeared at Jefferson Barracks, the Army camp nearest St. Louis, causing its commander to declare a quarantine. But it wasn't until October 7, when civilian cases began to spike in St. Louis, that Starkloff acted. Inviting to his office the mayor; municipal health officers; representatives from the PHS, the medical community, hospitals, and the public school system, and ARC chapter and division leaders, he presented them with a proclamation that closed schools, meetings, conventions, and public places of amusement, and granted him authority to take all steps to protect the city. A second proclamation closed houses of worship. The attendees voted unanimously to accept both.52–56

During the pandemic, the chapter worked closely with Starkloff to organize nurses, supplies, food for convalescents, transportation for nurses and patients, and information. Its nursing services committee drew up a plan dividing the city into districts and assigning health department nurses, along with aides and lay volunteers, to each district. With Starkloff's approval, the chapter opened offices to register nurses, aides, and volunteers, and assign them to work with health department nurses. Additionally, the chapter sent 103 nurses and nursing aides to Jefferson Barracks and local hospitals treating enlisted men. Finally, in an indication that the St. Louis chapter viewed its responsibilities differently than its Pittsburgh counterpart did, the chapter cooperated with the division influenza committee to send nurses, aides, and nursing volunteers to surrounding Missouri towns.51,57,58

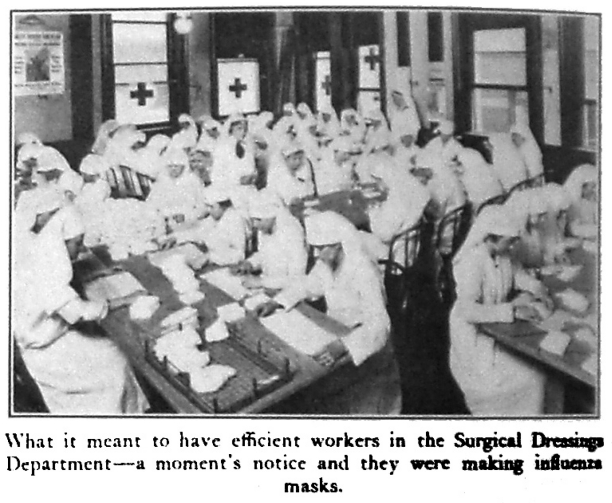

Like other chapters, the St. Louis chapter converted its surgical dressings workshop into an influenza mask workshop to turn out “large quantities” of masks for nurses, hospitals, and military camps (Figure 2). The chapter also collected donations, from bed linen and warm clothing for infants, children, and adults, to 100 quarts of milk per day provided by the Tuberculosis Society. It then gave these donations to the nurses and other municipal workers to distribute. Chapter volunteers also cooked meals for patients at community kitchens opened by the U.S. Food Administration, and provided patients with soups, broths, and custards.51

Figure 2.

American Red Cross volunteers making influenza masks during the 1918–1919 pandemic

Source: American Red Cross. Potomac Division bulletin, illustrated supplement. How the Red Cross met the influenza epidemic. 1918 Nov 22. Box 520, Record Group 200, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

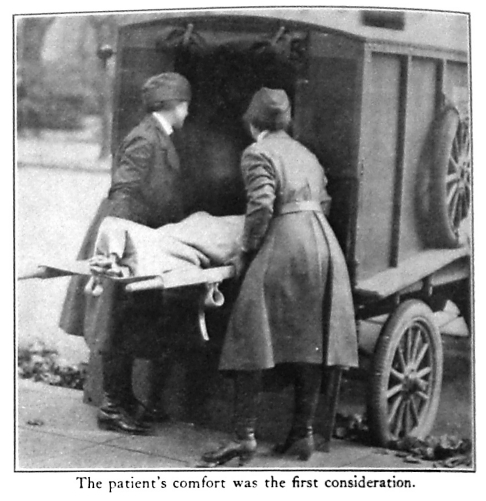

As in other cities, the chapter's motor corps provided transportation (Figure 3). Operating five ambulances around the clock, the motor corps transported as many as 101 patients in a single day. One corps ambulance stood duty at the main train depot, Union Station. After a train pulled into this cross-country transportation hub, motor corps volunteers removed passengers who had become sick with influenza en route. These patients were cared for by members of the chapter's canteen service and whisked away in a Red Cross ambulance. Another ambulance stationed at Jefferson Barracks transported sick soldiers. The motor corps' members also used their private cars to drive nurses on daily rounds of visits.51

Figure 3.

Motor corps volunteers transporting influenza patients during the 1918–1919 pandemic

Source: American Red Cross. Potomac Division bulletin, illustrated supplement. How the Red Cross met the influenza epidemic. 1918 Nov 22. Box 520, Record Group 200, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

St. Louis experienced one of the lowest influenza rates of any comparable-sized city, and the Red Cross took some credit for this result. Public health nurses told the chapter its volunteers had enabled them to work more efficiently, and thus serve more patients. Jefferson Barracks' chief military officer “stated that they were very quickly able to overcome the epidemic because of the number of nurses and Red Cross nurses aides with which the Red Cross immediately supplied them,” according to Hammar.10,51

Another intervention that may have helped reduce influenza was the chapter's distribution of PHS influenza prevention pamphlets. Southwestern division headquarters printed 1.2 million copies of the pamphlets, which offered straightforward information on influenza. These four-page pamphlets, which stated boldly across the top, “Read This and Protect Yourself Against Epidemic,” were “distributed widely throughout the city,” according to Hammar. The pamphlets addressed the nature and origin of the “Spanish” influenza, its airborne manner of infection, and its symptoms and complications, while providing tips on how to avoid contracting the flu. It advised people to maintain health through rest and proper nutrition, try to “reduce home overcrowding to a minimum” and keep windows open, avoid “crowds and stuffy places” by walking to work if possible rather than taking public transport, keep “the face so turned as not to inhale directly the air breathed out by another person,” and to be wary of those who cough or sneeze without covering the mouth and nose. “Cover up each cough and sneeze, If you don't you'll spread disease,” a catchy couplet at the end of the pamphlet admonished. The pamphlet additionally advised those experiencing symptoms to “go home at once and go to bed” to prevent “dangerous complications” and “keep the patient from scattering the disease far and wide.” It further advised against allowing anyone to sleep in the same room as an influenza patient, but stipulated that nurses should be allowed in the room.59

ARC divisions and chapters distributed numerous similar pamphlets. One pamphlet included simple influenza prevention instructions in eight languages, including English, Polish, Russian, Yiddish, Hungarian, Italian, Bohemian (Czech), and Spanish. These instructions, such as the admonition, “don't spit on the floor or the sidewalk anywhere. Do not let other people do it,” conveyed a paternalistic tone reminiscent of tuberculosis prevention messages distributed during that era in urban immigrant communities. Newspapers also reprinted summaries of the instructions.60–66

A well-coordinated partnership between volunteer and government sectors, St. Louis' successful experience demonstrates the value of well-organized voluntarism in a health emergency. It comes as no surprise, however, that the Red Cross functioned so well in a city where the overall public health response proved so speedy, thorough, and exemplary.

RICHMOND: RED CROSS ONE AMONG MANY VOLUNTEER GROUPS

The influenza response in Richmond contrasted sharply with those in St. Louis and Pittsburgh, although the flu arrived in all three places almost simultaneously. On September 29, Richmond health authorities announced the city's first civilian case. But Camp Lee, a military installation half as big as the city itself and only 26 miles away, had been battling influenza since September 14. Although Camp Lee had reported thousands of cases and numerous deaths by the end of the month, no general quarantine had been imposed at the camp, with its accommodations for 60,335 men. Richmond authorities had considered barring servicemen from entering the city while on leave, but Dr. Roy Flannagan, head of the Richmond Health Department, decided against this measure. As such, it became inevitable that influenza would spread to Richmond.67–74

In September, volunteers from the Richmond chapter began ministering to sick soldiers at Camp Lee. They investigated and answered inquiries from soldiers' relatives as to the soldiers' welfare; supplied convalescents with “jellies, fruits and other delicacies, in generous quantities;” and cared for sick soldiers' relatives. They provided “cots and beds when hotels became over-crowded,” established a “convalescent house” where 12 to 18 relatives could stay for free, and drove relatives to and from the train depot. In one case, “[a] soldier's wife came from Texas to see her husband, but upon her arrival found that he was in quarantine. The day after her arrival [at Camp Lee] she was taken ill with influenza, which caused the expenditure of the funds that she had intended to return to Texas on. This was another case for the Red Cross,” a Richmond-Times Dispatch article stated. The Richmond chapter also provided thousands of gauze masks for use by physicians and assistants at the camp, and sent volunteers to an emergency hospital for servicemen opened at Richmond College.75,76

When influenza struck the Richmond civilian population, however, other groups spearheaded the volunteer response. Maude Cook, a Richmond woman who kept a registry of trained nurses, immediately began fielding calls for nursing assistance. On October 2, Dr. Flannagan and the state's health commissioner invited “every man and woman, white and colored, who has any experience in nursing” to a public meeting at the downtown Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA) building. The 75 nurses who attended issued a further call for all volunteers who had taken the Red Cross home hygiene course. The city health department outfitted the volunteer nurses with uniforms and disinfectants, and while the chapter provided nursing bags filled with pharmaceutical agents, disinfectants, and gauze masks, it played little role in organizing nursing care. As in St. Louis, health authorities divided the city into districts to efficiently allocate resources. But here, local medical students, not ARC nurses, made house calls in the districts, and public school teachers visited the sick in their school districts. In mid-October, Boy Scouts and Campfire Girls conducted a door-to-door survey of the city to uncover 1,755 previously unreported influenza cases, while the Instructive Visiting Nurse Association organized soup kitchens for influenza patients. U.S. Department of Agriculture food experts aided this endeavor by producing 100 gallons of soup per day at a local dehydration plant, while volunteer women from local churches staffed the kitchens. The “colored” YWCA also ran its own soup kitchen. The ARC chapter, then, operated as just one among many volunteer groups during the pandemic.77–83

As influenza cases approached their peak in Richmond, the ill-funded city health department launched a $50,000 fund drive for influenza care. These funds were used to convert the city's John Marshall High School into an emergency hospital. In keeping with Southern patterns of racial segregation, white patients were treated in the main area, while black patients were treated in the basement. Volunteers from all sectors of Richmond society stepped forward to volunteer at the hospital. Prominent local women, such as Mrs. Westmoreland Davis, the governor's wife, and Mrs. Maggie Lena Walker, the first female and first African American bank president in the U.S., worked at the hospital, alongside Catholic nuns and agricultural extension agents. The Boy Scouts started an ambulance service and the Young Men's Hebrew Association opened a convalescent ward nearby. Jack Williams, a 15-year old Boy Scout volunteer, worked until exhausted then succumbed to influenza.80,84–88

The ARC chapter contributed to this effort, but did not lead it. The chapter donated $10,000 to the hospital fund drive and supplied the first 250 beds to the hospital, as well as 580 pillowcases, 230 pajamas, sheets, bathrobes, slippers, handkerchiefs, and other items that its volunteers had sewn to be sent to a hospital in France. In early October, Red Cross volunteers began making hospital supply items at the chapter workroom, and called upon others to make gauze masks in their homes. The volunteers, including members of a Catholic women's auxiliary, made a total of 15,115 items, including nightgowns, sheets, pillowcases, towels, pneumonia jackets, face masks, and other supplies, while also baking rolls for convalescent patients. After a local doctor stated publicly that face masks should be worn to prevent influenza, people lined up in front of the chapter's headquarters to procure them. The chapter, which sold the masks to the public for two cents a piece, had to turn people away until more masks could be made.79,89–92

On October 24, the day Richmond's epidemic was officially pronounced “in decline,” volunteers from the ARC motor corps in Washington arrived to organize a women's motor corps at the chapter. About 50 women attended the meeting to hear that the corps would be allocated “two ambulances, two motor trucks, one touring car and one motorcycle.” The corps became organized in early November, and “did excellent work during the influenza epidemic,” according to a division report. But although Richmond experienced a brief recrudescence of the flu beginning in late November, the motor corps came late to the job.75,93

The Richmond chapter's response to the influenza pandemic cannot be seen, however, as a failure. The chapter, in keeping with the ARC's wartime priorities, devoted its limited resources to aiding nearby servicemen and their families. But it lacked sufficient numbers of volunteers to fight a civilian epidemic as well. The fact that other voluntary groups stepped in to fill this gap—as they did in other cities—demonstrates that the ARC at the local level was not quite as irreplaceable as national headquarters insisted it was.

CONCLUSION: LOCALISM PERSISTS

In 1908, Clara Barton reflected, “My work was, and chiefly has been, to get timely supplies to those needing.” In this narrow mission, the ARC succeeded during the influenza pandemic. But national headquarters had wanted the chapters to do more than provide gauze masks, soup, and hospital garments: it had wanted them to coordinate health care and health communication. This goal sometimes conflicted with the ARC's wartime mission of serving the military, and chapters prioritized the war effort over general public health. But a more significant obstacle to this nationally coordinated mission proved to be the stubborn localism of ARC chapters. In the cities examined in this article, the willingness and ability of chapters to follow national mandates varied greatly.1,94

Nevertheless, ARC localism did not always work to the detriment of the cities involved. Boston chapter leaders responded more promptly and innovatively than they would have if they had waited for directions from headquarters. The Pittsburgh and St. Louis chapters demonstrated how a close working relationship with local health departments promoted effective mobilization of nurses and volunteers. These cases further illustrate how the voluntary sector can aid greatly in distributing resources and information, and in connecting people to resources during a pandemic. But the Richmond case suggests that ARC voluntarism had its limits, especially in smaller cities with smaller chapters.

As the public welfare safety net of the 1910s consisted mainly of locally based organizations, such localism in the influenza response comes as no surprise. While the federal government, upon entering the war, tried to seize control of key resources through entities such as the Food Administration, the Selective Service Board, and the ARC War Council, it lacked the time or funds to build a nationally diffused infrastructure to enforce its mandates, and had to rely on local volunteers, whether to register draftees or to fight influenza. These volunteer-staffed operations often worked surprisingly well, primarily because they were supported by a pervasive ideology promoting volunteer work as an obligation of citizenship and casting public approbation on those who refused to participate. But as these case studies illustrate, local volunteers did not always carry out their duties the way Washington wanted them to.17,26,36

While much has changed since 1918, localism persists in public health emergency preparedness. State and local health departments, together with private physicians, still form the first line of response for pandemics. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' current Pandemic Influenza Plan reflects this reality. “During the first wave of the pandemic, outbreaks may occur simultaneously in many locations throughout the nation, preventing a targeted concentration of national emergency resources in one or two places—and requiring each locality to depend in large measure on its own resources to respond,” the plan states.95

This focus on local capabilities for pandemic response has assumed heightened importance in light of the current experience with H1N1. Researchers studying the response to H1N1 have noted “substantial variation in scope and timing of local public health response.” Public health departments have been found to vary widely in their resources, training, and capabilities to meet the pandemic, as well as their level of coordination with other local authorities such as school districts, and with state health departments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These findings, while tentative, suggest that critical gaps exist at the local level. Voluntary organizations could prove useful in filling these gaps, as they did in 1918. Although voluntarism today has not reached the frenzied 1918 levels, more than 700 ARC chapters along with numerous other voluntary organizations still constitute an important resource for local public health departments. Local partnerships and advance planning exercises that include voluntary organizations could prove beneficial in current and future pandemic response.9,96,97

REFERENCES

- 1.Red Cross National Committee on Influenza Chairman. Folder 803, Epidemics, Box 687, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 5, Inter-office memo to all division managers. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosby AW. America's forgotten pandemic: the influenza of 1918. Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Red Cross War Council. The work of the American Red Cross during the war: a statement of finances and accomplishments for the period Jul 1, 1917 to Feb. 28, 1919. Washington: American Red Cross; 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persons WF. Folder 803, Epidemics influenza 1918 divisions, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 3, Night letter to Atlantic division manager, New York City. [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Red Cross. The mobilisation of the American National Red Cross during the influenza epidemic, 1918–1919. Geneva: Printing Office of the Tribune de Geneve; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Box 520, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 14, Precautions against epidemic. Important items; American Red Cross Southwestern division (bulletin) p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dock LL, Pickett SE, Noyes CD, Clement FF, Fox EG, Van Meter AR. History of American Red Cross nursing. New York: MacMillan Co.; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schleif R. No lines here: appointments for H1N1 shots. Wenatchee World. 2009. Nov 11, [cited 2009 Nov 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.wenatcheeworld.com/news/2009/nov/11/no-lines-here-appointments-for-h1n1-shots.

- 9.Wayne B, Klaiman T, Dearinger A, Wilfert R, Marti C, Mays G, et al. Session 3050.1: Variation in local public health response to the 2009 H1N1 outbreak: comparative analyses from across the U.S.; American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; Philadelphia: 2009. Nov 9, [cited 2009 Nov 20]. Abstracts available from: URL: http://apha.confex.com/apha/137am/webprogram/Session28438.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA, Sloan A, Michalsen J, Stern A, et al. Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by U.S. cities during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA. 2007;298:644–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bremner RH. American philanthropy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bremner RH. The public good: philanthropy and welfare in the Civil War era. New York: Knopf; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton C. The Red Cross of the Geneva Convention: what it is. Washington: Rufus H. Darby; 1878. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosar K. CRS Report No. RL33314. Washington: Congressional Research Service; 2006. The congressional charter of the American National Red Cross: overview, history, and analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaeddert G. Washington: American Red Cross. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1950. The Boardman influence, 1905–1917. The history of the American National Red Cross [unpublished monograph by American Red Cross History division] Box 765, Group 2, RG 200. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dulles FR. The American Red Cross: a history. New York: Harper; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clements KA. The presidency of Woodrow Wilson. Lawrence (KS): University Press of Kansas; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Red Cross. Washington Bureau of Publicants. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1917. The American Red Cross organization and activities. Folder 800.08, Statistics, Box 675, Group 2, RG 200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The business side of the Red Cross. Red Cross Magazine. 1918 Dec;:21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cutlip SM. Fund raising in the United States: its role in America's philanthropy. New Brunswick (NJ): Transaction Publishers; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Officer LH, Williamson SH. Measuring worth. Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago; 2006. [cited 2009 Nov 18]. updated 2009 Apr 2. Available from: URL: http://www.measuringworth.com. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cott NF. The bonds of womanhood: woman's sphere in New England, 1780–1835. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welter B. The cult of true womanhood: 1820–1860. American Quarterly. 1966;2:151–74. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginzburg LD. Women and the work of benevolence: morality, politics and class in the nineteenth-century United States. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott AF. Natural allies: women's associations in American history. Urbana (IL): University of Illinois Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capolozza C. Uncle Sam wants you: World War I and the making of the modern American citizen. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cash FB. African American women and social action: the clubwomen and volunteerism from Jim Crow to the New Deal, 1806–1936. Westport (CT): Greenwood Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elmore JA. Nurses in American history: black nurses: their service and their struggle. J Am Nurs. 1976;76:435–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyle ST. Paul Robeson: the years of promise and achievement. Amherst (MA): University of Massachusetts Press; 2001. p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Folder 803.11, Epidemics influenza Massachusetts, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Nov 18, What the Boston Metropolitan chapter of the Red Cross accomplished during the epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson J. Folder 803.11, Epidemics influenza Massachusetts, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Sep 23, Telegram to SM Greer, American Red Cross, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson J. Folder 803, Epidemics influenza 1918 divisions, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 4, Letter to W. Frank Persons, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Director of Civilian Relief, New England division, American Red Cross. Folder 803, Epidemics influenza 1918 divisions, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 17, Letter to Miss Marjorie Perry, Burlington, Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Director of Civilian Relief, New England division, American Red Cross. Folder 803, Epidemics influenza 1918 divisions, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 16, Letter to J. Byron Deacon, national headquarters. [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Red Cross organized for action. Red Cross Bulletin. 1917 Jul;28:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greely D. Beyond benevolence: gender, class and the development of scientific charity in New York City, 1882–1935 [dissertation] Stony Brook (NY): State University of New York at Stony Brook; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persons WF. Folder 803, Epidemics influenza 1918 divisions, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 25, Letter to division directors of civilian relief. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monroe FC. Folder 803, Epidemics influenza 1918 divisions, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1919. Mar 1, Letter to Red Cross division managers. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Again—the grip! Pittsburgh Gazette-Times. 1918 Oct;1:6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.11 more deaths from influenza. Philadelphia Enquirer. 1918 Oct;1:17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods EA. Folder 803.11, Epidemics, influenza Pennsylvania, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1919. Jan 14, Supplemental report memoranda as to some of the methods employed in the influenza campaign by the Pittsburgh chapter of the American Red Cross. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paulin DC. Folder 803.11, Epidemics, influenza Pennsylvania, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Dec 18, Report of sub-committee on relief and rehabilitation of the influenza committee of the Pittsburgh chapter, American Red Cross. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynch EA. The flu of 1918. The Pennsylvania Gazette. 1998. Nov, [cited 2009 Jun 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/1198/lynch.html.

- 44.Peterson ER. Folder 803.11, Epidemics, influenza Pennsylvania, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1920. Jan 28, Unfinished monograph on Pittsburgh chapter's work in influenza. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Real vaccine for influenza will be made. Pittsburgh Gazette-Times. 1918 Oct;25:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Folder 803.11, Epidemics, influenza Pennsylvania, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; Rules governing the distribution of supplies by the influenza committee of the Pittsburgh chapter, American Red Cross. Undated. [Google Scholar]

- 47.American Red Cross, Pittsburgh chapter. A history of the activities of the chapter from its organization to January 1, 1921. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Co.; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lists of grip victims show big increase. Pittsburgh Gazette-Times. 1918 Oct;8:1. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Officials plan hospitals for grip patients. Pittsburgh Gazette-Times. 1918 Oct;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peterson ER. Folder 803.11, Epidemics, influenza Pennsylvania, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1920. Jan 28, Letter to John H. McCandless, director, Bureau of Disaster Preparedness and Organization, Dept. of Civilian Relief., American Red Cross. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammar VC. Folder 803.11, Epidemics, influenza Missouri, Box 689, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Nov 16, Letter from Chairman of St. Louis chapter to Mrs. W. K. Draper, Chairman, Woman's National Advisory Committee American Red Cross, Washington. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doctors here must report influenza. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1918 Sep;20:2. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pneumonia cases 10 per cent of winter deaths; how to avoid it. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. 1918 Sep;21:11. [Google Scholar]

- 54.No quarantine here against influenza, says Dr.Starkloff. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1918 Oct;6:8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.To close schools and theaters to check influenza. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1918 Oct;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Influenza quarantine placed on city and schools, theaters, churches are to be closed. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1918 Oct;8:1. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sixteen city hospital attaches fall victim to Spanish influenza. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1918 Oct;15:1. [Google Scholar]

- 58.424 new influenza cases in St. Louis. St. Louis Globe-Democrat. 1918 Oct;14:4. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Supplement No. 34 to the Public Health Reports. Washington: United States Public Health Service; 1918. Sep 28, “Spanish Influenza,” “Three-Day Fever” “The Flu.”. Reprinted by the American Red Cross Southwestern division. Folder 803.7, Epidemics, influenza publicity and publications, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Folder 803.7, Epidemics, influenza publicity and publications, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 3, Letter from associate director, bureau of chapter organization to W. Frank Persons, chairman, committee to conduct campaign against Spanish influenza. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seattle American Red Cross. Vol. 1. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; 1918. Oct 12, Simple precautions to prevent influenza. Bulletin of the Northwestern division; p. 1. Box 520, Group 2, RG 200. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Folder 803.7, Epidemics, influenza publicity and publications, Box 688, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD: National Archives and Records Administration; How to protect yourself from influenza [pamphlet] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Billings JS. Department of Health of the City of New York Monograph Series 1. New York: Department of Health; 1912. The registration and sanitary supervision of tuberculosis in New York City. [Google Scholar]

- 64.City fights grippe with severe steps. The Washington Post. 1918 Oct;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 65.New gains in grip here. The New York Times. 1918 Oct;4:24. [Google Scholar]

- 66.“Flu” cases down in city and state. The Atlanta Constitution. 1918 Oct;24:7. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Influenza epidemic spreads to Richmond. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Department of the Army (US), Installation Management Command. Fort Lee history. [cited 2009 Jun 12]. (updated 2009 May 22) Available from: URL: http://www.ima.lee.army.mil/sites/about/history.asp.

- 69.90 die of influenza. The Washington Post. 1918 Sep;15:8. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Influenza in three camps. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Sep;18:5. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pneumonia causes six deaths at Camp Lee. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Sep;22:3. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Denies Virginia quarantine. The Washington Post. 918 Sep;17:3. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richmond may bar troops. The Washington Post. 1918 Oct;1:4. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Influenza safeguards taken by Dr. Flannagan. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;2:14. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Folder 149.18, Potomac division civilian relief reports 1918, Box 233, Group 2, RG 200. College Park, MD.: National Archives and Records Administration; 1919. Jan 23, Report of Potomac division for July–December 1918. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Good work of Red Cross recognized at Camp Lee. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;9:4. [Google Scholar]

- 77.More nurses needed. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Epidemic forces drastic action. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;5:1. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Close all fairs during epidemic. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;9:1. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Flu besieges city; 10,000 cases here. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;8:1. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grippe still rages in city. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;12:1. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Colored soup kitchen. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;22:6. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Supplying 100 gallons of soup a day to sick. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;14:10. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grippe crisis is reached, should ebb from now on. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;15:10. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Graduate nurses teach services in new hospital. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;16:12. [Google Scholar]

- 86.All helping sufferers in emergency hospital. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;13:4. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Catholics render help at emergency hospital. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;17:4. [Google Scholar]

- 88.J. S. Williams' nephew dead. The Washington Post. 1918 Oct;18:7. [Google Scholar]

- 89.314 new flu cases reported in city. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;13:1. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Grippe situation thought better. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;16:1. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Red Cross workrooms issue appeal for help. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Nov;9:2. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Plague continues to ravage state. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;10:1. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Many women will join Red Cross motor corps. Richmond Times-Dispatch. 1918 Oct;25:4. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pryor EB. Clara Barton professional angel. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1988. p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Department of Health and Human Services (US) HHS pandemic influenza plan. Part 2. [cited 2009 Jun 16];Public health guidance on pandemic influenza for state and local partners. 2005 Nov; (updated 2006 Jun 26) Available from: URL: http://www.hhs.gov/pandemicflu/plan/part2.html. [Google Scholar]

- 96.American Red Cross. About us. [cited 2009 Nov 20]. Available from: URL: http://www.redcross.org/portal/site/en/menuitem.d8aaecf214c576bf971e4cfe43181aa0/?vgnextoid=477859f392ce8110VgnVCM10000030f3870aRCRD&vgnextfmt=default.

- 97.Ganyard ST. All disasters are local. The New York Times. 2009 May;17:A23. [Google Scholar]