Abstract

Multivalency is the increase in avidity resulting from the simultaneous interaction of multiple ligands with multiple receptors. This phenomenon, seen in antibody-antigen and virus-cell membrane interactions, is useful in designing bioinspired materials for targeted delivery of drugs or imaging agents. While increased avidity offered by multivalent targeting is attractive, it can also promote nonspecific receptor interaction in non-target tissues, reducing the effectiveness of multivalent targeting. Here, we present a thermal targeting strategy - Dynamic Affinity Modulation (DAM) - using Elastin-like polypeptide diblock copolymers (ELPBCs) that self-assemble from a low-affinity to high-avidity state by a tunable thermal “switch”, thereby restricting activity to the desired site of action. We used an in vitro cell binding assay to investigate the effect of the thermally triggered self-assembly of these ELPBCs on their receptor-mediated binding and cellular uptake. The data presented herein show that: (1) ligand presentation does not disrupt ELPBC self-assembly; (2) both multivalent ligand presentation and upregulated receptor expression are needed for receptor-mediated interaction; (3) increased size of the hydrophobic segment of the block copolymer promotes multivalent interaction with membrane receptors, potentially due to changes in the nanoscale architecture of the micelle; and (4) nanoscale presentation of the ligand is important, as presentation of the ligand by micron-sized aggregates of an ELP showed a low level of binding/uptake by receptor-positive cells compared to its presentation on the corona of a micelle. These data validate the concept of thermally triggered DAM, and provide rational design parameters for future applications of this technology for targeted drug delivery.

Keywords: Block copolymer, polypeptide, multivalency, self-assembly, ligand-receptor

Targeted drug delivery, first proposed in 1906, 1 is a strategy for preferentially increasing the concentration of a drug at a target site relative to healthy tissue. An important goal in targeted therapy, hence, is to design a drug carrier that has high affinity and selectivity for the site of disease but exhibits low affinity for, and low interaction with, healthy tissue. Although high affinity vehicles can show greater accumulation at the site of disease as compared to normal tissues, 2 high affinity can also result in reduced specificity 3 and increased toxicity 4 because of “off-site” targeting to healthy tissue that also express the same receptor, albeit at lower levels. To circumvent this fundamental paradox, we hypothesized that an ideal targeted delivery system should have a low affinity for its target in healthy tissue but transform into a high affinity construct at the site of disease via an extrinsic trigger (e.g., a physical stimulus such as the focused application of heat, light or magnetic fields). We term this approach, in which a molecule morphs from a low affinity to a high affinity state in response to an external stimulus, Dynamic Affinity Modulation (DAM).

Our design of a system that is capable of exhibiting DAM focused on triggered self-assembly. Multivalency, the simultaneous interaction of multiple ligand-receptor pairs, is described by:

| (1) |

where Kmulti is the effective multivalent affinity (avidity), Kmono is the affinity of a single receptor-ligand interaction, α is the degree of cooperativity, and N is the number of ligand-receptor pairs. 5 Thus, multivalency provides a large increase in avidity proportional to the number of simultaneous ligand-receptor interactions. Although conventional, “static” multivalent targeting is an emerging approach for targeted delivery, it suffers from the same problem of “off-site targeting” as monovalent, high-affinity delivery systems. 6

We hypothesized that multivalency via triggered self-assembly would permit the design of a targeted delivery system exhibiting DAM. In order to design a system that could self-assemble into a multivalent construct in response to an external stimulus (Fig. 1a), we focused our attention on a class of diblock, stimulus-responsive elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs). ELPs are genetically encoded polypeptides comprised of a Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly repeat (Xaa = any amino acid besides Pro) that exhibit inverse phase transition behavior at a specific transition temperature (Tt); ELPs are soluble in water at T < Tt and become insoluble at T > Tt. 7–9 We chose diblock ELP block copolymers (ELPBCs) to create a system capable of DAM for several reasons. First, we and others have previously shown that ELPBCs consisting of one hydrophilic and one hydrophobic ELP block are temperature triggered amphiphiles; the ELPBC is a hydrophilic unimer that self-assembles into monodisperse spherical micelles with a diameter of ~40 – 60 nm above a critical micelle temperature (CMT) through selective desolvation and collapse of the hydrophobic block. 10, 11 These micelles are stable with increasing temperature (typically ~8 – 10 °C beyond the CMT) up to a second transition temperature, beyond which the desolvation and collapse of the hydrophobic block leads to aggregation of the ELPBC into polydisperse micron-sized aggregates. 7 Second, ELPBCs are monodisperse, which provides exquisite control over their self-assembly and, consequently, the size and coordination number of the micelle. This precise control is not readily possible with synthetic polymers. 10 Third, ELPBCs can be easily expressed at high levels in E. coli and conveniently purified by inverse transition cycling (ITC), 12 a method that exploits the ELP phase transition to purify them directly from cell lysate without chromatography.

Figure 1.

(a) Schema of DAM via temperature triggered self-assembly of an ELPBC. At T < CMT, ELPBC exist as soluble unimers and lead to monovalent ligand presentation. At T > CMT, the ELPBC unimers self-assemble into micelles following desolvation and collapse of the hydrophobic block. This leads to multivalent ligand presentation in the corona of the micelle.(b) The ELPBCs incorporate an RGD peptide ligand at the hydrophilic terminus and a cysteine residue for conjugation of fluorophores (or drugs) at the hydrophobic terminus. The ligand-negative, control ELPBC does not contain the terminal RGD ligand but includes the C-terminal cysteine.(c) SDS-PAGE of purified RGD-ELPBCs (left) and parent ELPBCs (right) yields a thick band corresponding to monodisperse purified protein, showing that ELPBC can be purified by ITC.

We chose the linear GRGDS peptide as the ligand and the αvβ3 integrin as the target receptor to demonstrate proof-of-concept of DAM using ELPBCs as the scaffold to present the RGD peptide ligand (Fig. 1b). GRGDS is a well-known, low affinity ligand (IC50 = 1 µM) for the αvβ3 integrin. 13 The low affinity of this ligand reduces specific binding in monovalent form 13 but can exhibit higher effective affinity through multivalent presentation. 5 First, we hypothesized that linear GRGDS is a useful ligand for DAM as the large difference in affinity between its multivalent and monovalent states provides the possibility for selective receptor binding only through multivalent presentation so that this construct would localize in a target tissue that overexpresses the receptor in response to spatially focused mild hyperthermia of that tissue. Second, the αvβ3 integrin is overexpressed in angiogenic blood vessels that are associated with diseases such as cancer, 14, 15 atherosclerosis, 16, 17 and Alzheimer’s disease, 18 ensuring that this approach may be relevant to a number of diseases. Third, the RGD ligand is somewhat promiscuous as it binds to the αIIBβ3 integrin on activated platelets and the αvβ3 integrin on healthy angiogenic tissue 19 in addition to tumor vasculature. Thus, restricting RGD activity to a target organ or tissue through externally triggered self-assembly would yield a benefit to this particular targeting strategy. Fourth, the αvβ3 integrin exhibits clustering during activation, 20 which should help promote the proper geometry for multivalent interaction of receptors with RGD ligands presented on an ELPBC micelle. Fifth, the linear, hydrophilic GRGDS peptide is trivial to incorporate on one of the termini of the ELP via genetically encoded synthesis 10 without disrupting self-assembly of ELPBCs into micelles.

This study investigates two important issues relevant to the design of a targeting system based on DAM using stimulus-responsive ELPBCs as a self-assembling macromolecule and mild hyperthermia as the trigger. First, the high-avidity state of the ELPBC must be turned “on” in response to an external trigger. Second, the size and architecture of the ELPBC micelle must facilitate multivalent interaction following ligand presentation through self-assembly. The studies presented herein attempt to address these issues by examining, in detail, the effects of both multivalency and nanoscale architecture on the interaction of a set of ELPBCs with a target membrane-based receptor. We chose three self-assembling diblock ELPBCs that vary in the hydrophobic-hydrophilic segment ratio (SR) and used these to:(1) demonstrate thermal self-assembly as a trigger for receptor-mediated binding activity and (2) identify the optimal nanoscale architecture for multivalent interaction of the micelles with the αvβ3 integrin.

Results

We chose parent ELPBCs that were available from previous studies, 10, 21 to examine the size and nanoscale architecture of their micelles on DAM. Each ELPBC(defined hereafter as ELP-Y/Z) is comprised of a hydrophilic block of Y VPGXG repeats (where X = V:A:G in a 1:7:8 ratio) and a hydrophobic block of Z VPGVG repeats. We chose three separate ELPBCs for this study, ELP-96/60, ELP-64/60, and ELP-64/90, that span a SR range of 0.66 to 1.5 (Fig. 1b). We have previously shown that each of these ELPBCs self-assembles into micelles in response to an increase in solution temperature, 10 and this range of SRs allowed us to study the effect of nanoscale architecture on multivalent interaction between the ligand and receptor. Two variants of homopolymeric ELP that comprise of 150 VPGXG (where X = V:A:G in a 5:3:2 ratio, ELP-150) were also synthesized, one of which has a terminal RGD peptide and negative control lacking the RGD peptide, serving as controls to examine the effect of nanoscale presentation.

ELPBCs were modified at the gene level to attach a GRGDS ligand at their N-terminus and a unique cysteine residue on their C-terminus. Each modified ELPBC was expressed from a plasmid-borne synthetic gene in E. coli which encoded three contiguous segments: an N-terminal GRGDS peptide ligand, the ELPBC and a short WPC peptide that provides a unique cysteine residue for conjugation of a fluorophore or drug at the C-terminus (Fig. 1b). ELPBCs that contained the C-terminal WPC sequence but not the N-terminal GRGDS ligand served as a negative control for the effect of ligand presentation.

Each ELP was recombinantly synthesized by inserting each parent ELPBC gene into a modified pET25b expression vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) with subsequent overexpression of the ELPBC genes in E. coli. Agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA sequencing demonstrated successful cloning of RGD-modified ELPBC and ELP genes lacking the RGD peptide into expression vectors (data not shown). All constructs were expressed from their plasmid-borne genes in E. coli at high yields (> 50 mg/L in shaker flask culture) and were purified by inverse transition cycling (ITC). 12 SDS-PAGE showed that the ELPs were monodisperse and were purified to homogeneity by ITC (Fig. 1d). The purified ELPs were then conjugated to AlexaFluor488 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by reaction between the maleimide moiety of the fluorophore and the terminal cysteine of the ELPBCs and ELP-150 with a yield of 60 – 70%. Labeled constructs were used for all subsequent experiments.

We characterized the thermally triggered self-assembly of the ELPBCs by dynamic light scattering (DLS). We monitored the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) and coordination number (Z) of a 10 µM ELP solution as a function of temperature. Both RGD-ELPBC and the parent ELPBC exhibited two phases as the solution temperature was raised from 20 °C – 42 °C:(1) a soluble unimer phase with a Rh = 5 – 8 nm and (2) a nanoparticle with a Rh of ~30 nm at higher temperatures (Fig. 2a). The coordination number (Z), defined as the number of unimers comprising one micelle, was determined for each construct and allowed estimation of the ligand density of RGD moieties in the corona which was similar for all RGD-ELPBC constructs of different SRs (Fig. 2b). This ligand density is within the range of densities required for multivalent RGD-αvβ3 interaction 22 and supports the use of these constructs for multivalent targeting of the αvβ3 integrin.

Figure 2.

Dynamic, thermally triggered self-assembly of RGD-ELPBCs and ELPBCs. Hydrodynamic radius (Rh) and molecular weight (MW) of the ELPBCs were measured as a function of temperature by DLS.(a) Both ELPBCs exhibit distinct and stable unimer and micelle regions as a function of solution temperature. The temperature at which the unimer to micelle transition occurs is defined as the CMT (dashed line). (b) Presentation of the RGD peptide ligand on the hydrophilic terminus of the ELPBC altered the self-assembly properties of the ELP-64/90 less than the ELP-96/60 or ELP-64/60 constructs. The resulting terminus density was nearly identical for all ligand and non-ligand constructs.

After verifying thermally-triggered self-assembly, we examined the feasibility of DAM using the ELPBCs as the thermosensitive carrier, linear RGD peptide as the ligand, AlexaFluor488 as the surrogate for an imaging agent or drug, and mild hyperthermia as the thermal switch. For DAM to be successful using RGD-ELPBCs, four requirements must be met. First, RGD-ELPBC must exist in an “off” state below its CMT; it must not interact with cellular receptors in its hydrophilic, monovalent state. This would ensure that RGD-ELPBC does not interact with cell receptors outside the target area. Second, self-assembly of ELPBC into micelles must not promote cellular interaction independent of ligand presentation. This is an important consideration, as it would allow the ELPBC to act as a scaffold for multivalent ligand presentation without directly enhancing non-specific binding or uptake by cells. Third, RGD-ELPBC must exist in an “on” state above the CMT; RGD-ELPBC micelles should lead to enhanced interaction with receptor-positive cells compared to receptor-negative cells. Meeting this last requirement would prove the ability for controlled multivalency to act as a trigger for receptor-specific cell interaction. Fourth, the RGD-ELPBC micelle must provide the optimal nanoscale architecture to allow multivalent interactions with cell surface receptors.

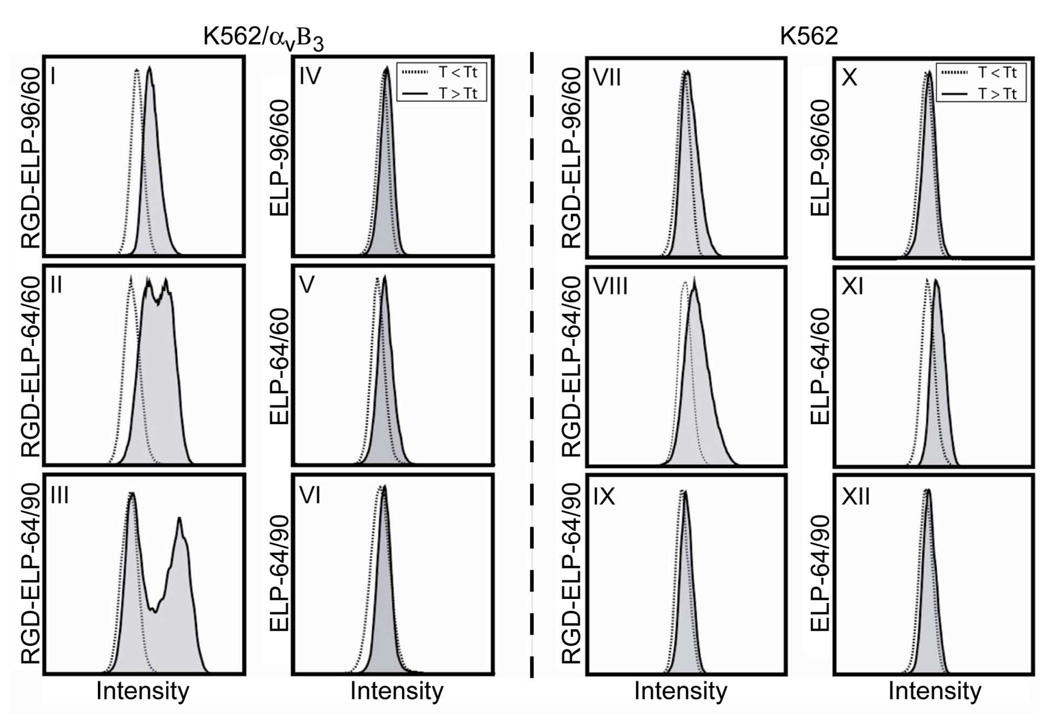

To test the four requirements for DAM, we measured cellular binding and uptake of the ligand-functionalized RGD-ELPBC and corresponding ligand-negative ELPBC controls by wild-type K562 human leukemia cells (receptor-negative control) and K562 cells transformed with the αvβ3 receptor (K562/αvβ3). 23 Briefly, 10 µM of either AlexaFluor488-labeled RGD-ELPBC or ELPBC were incubated with K562 or K562/αvβ3 for 1 hour at T < CMT (T = 23 °C) or T > CMT (T = 40 °C). These temperatures were chosen to ensure consistent temperatures for monovalent and multivalent presentation of all constructs. The cells were then analyzed for fluorescence intensity using flow cytometry (Fig. 3). Each panel corresponds to a unique pair of ELPBC and cell line, and the data in each panel are normalized to the flow cytometry distribution for that ELPBC below its CMT (dashed distributions). The relevant data is the increase in fluorescence for the ELPBC above the CMT (distribution in grey) relative to its cell uptake/binding below its CMT. Cell fluorescence, a measure of ELPBC binding and uptake, was then quantified using flow cytometry histograms to determine the potential of ELPBC to exhibit DAM. These results were independently verified with confocal microscopy (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry analysis of K562 and K562/αvβ3 cells following incubation with 10 µM RGD-ELP-64/90 or ELP-64/90 below (dashed line) and above (solid line) the CMT. There was no significant difference in the histograms of any of the cell populations incubated below the CMT. Neither cell line showed enhanced binding/uptake of the ELPBCs above their CMT, as seen by their similar flow cytometry histograms (panels IV–VI; X–XII), and the RGD-ELPBCs did not show appreciable interaction with K562 cells above the CMT (panels VII–IX). There was a slight increase in binding/uptake of RGD-ELP-96/60 above its CMT by K562/αvβ3 cells, but there was a dramatic increase in the fraction of K562/αvβ3 cells that take up RGD-ELP-64/60 and RGD-ELP-64/90 above their CMT (panels I–III). This of this second peak increasingly shifted right with increasing SR of each ELPBC indicating greater levels of interaction per cell.

Figure 4.

Analysis of segment ratio (SR) on cellular binding/uptake.(a) Approximately 60% of K562/αvβ3 were positive for the αvβ3 receptor as seen by the binding of the LM609 antibody that is specific for the αvβ3 integrin. The percentage of AlexaFluor488+ cells increased to 50%–60% relative to unheated controls when RGD-ELP-64/90 and RGD-ELP-64/60 were incubated with K562/αvβ3, similar to the % of αvβ3 cells. There was no significant increase in % AlexaFluor488+ cells with heating for any other combination of construct and cells. (b) The fold-increase in median fluorescence of AlexaFluor488+ cells was measured for each cell/construct combination. There was a small increase in fluorescence of both cell lines incubated with the parent ELPBCs and of K562 cells that were incubated with RGD-ELPBCs. The median fluorescence of αvβ3increased with RGD-ELP-64/60 and RGD-ELP-64/90 above their CMT, while there was a slight increase in binding of RGD-ELP-150 and RGD-ELP-96/60 by αvβ3. The median fluorescence also increased with increasing SR of the RGD-ELPBCs.

We first evaluated the effects of monovalent ligand presentation on specific cell interaction by incubating RGD-ELPBC or ELPBC with both cell types below the CMT and analysis by flow cytometry. The distribution of each cell population incubated below the CMT is designated by dashed lines in each panel in Fig. 3. As seen in the fluorescence histograms, there was little difference between the fluorescence intensity of any of the cell populations incubated with either ELPBC below the CMT. Confocal fluorescence images supported these findings as there was no visible fluorescence in cells incubated with RGD-ELPBC(Fig. 4) or ELPBC(data not shown) below the CMT. These results suggest that the K562 and K562/αvβ3 cell lines exhibit low levels of non-specific binding and uptake of the ELPs under these experimental conditions in contrast to other cell lines that show some, albeit low, levels of interaction with ELP. 21, 24 These data also indicate that monovalent presentation of RGD by ELPBC is not sufficient to promote cell interaction beyond that of the parent ELPBC, satisfying one criterion for DAM.

We next evaluated the effect of self-assembly on non-specific cellular binding and uptake (i.e., in the absence of the RGD ligand). We incubated ligand-negative control polymers below and above their CMT with K562 and K562/αvβ3 cells, respectively, and analyzed specific cell interaction of the ELPs by flow cytometry (Fig. 3). We quantified these differences by first obtaining a histogram corresponding to unheated cells and defining the region two standard deviations (SD) above the mean fluorescence as a significant increase in fluorescence intensity (AlexaFluor488+). This region was identified in each histogram of heated cells incubated with the same concentration of ELPBC. The fraction of heated cells within this region was used as one metric to quantify the effects of self-assembly on cellular interaction (Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

Confocal fluorescence images of K562/αvβ3 cells following incubation with 10 µM of various ELPBCs (green).(a) There was no visible binding of any of the ELPBC by K562/αvβ3 cells when they were incubated below and above the CMT with the ligand-negative ELPBC controls, demonstrating that micelle formation alone does not promote nonspecific interaction. (b) There was also minimal visible binding/uptake of all three RGD-ELPBC below or above the CMT when incubated with K562 cells, showing that overexpression of the receptor is necessary for enhanced interaction. (c) There was no visible binding/uptake of RGD-ELP-64/60 or RGD-ELP-64/90 below the CMT by K562/αvβ3 cells, but there was significant binding/uptake of RGD-ELP-64/60 or RGD-ELP-64/90 above their CMT. A binary population of highly fluorescent and non-fluorescent cells in the field of view was observed by fluorescence microscopy, corresponding to the bimodal distribution seen in the flow cytometry histogram in panels II and III in Fig. 3. Size bar = 50 µM.

These data reveal that the effect of heat on cell binding and uptake of ELPBCs was similar in either cell line. The flow cytometry data show that the distribution of fluorescence intensities did not significantly change at T > CMT relative to T < CMT in either cell line. Quantitatively, only < 10% of the heated cells showed significantly higher fluorescence intensity than the unheated control. These results clearly show that the cells did not interact more with control ELP at T > CMT compared to the same ELP at T < CMT and thus indicate that the effect of temperature triggered self-assembly on cell interaction was minimal for both cell lines in the absence of the RGD ligand (Fig. 5a). Confocal images of ELPBCs in both cell types visually confirmed the absence of significant fluorescence both below and above the CMT (Fig. 4), corroborating the flow cytometry data. Clearly, micelle formation by itself does not significantly promote cellular binding and uptake, demonstrating that ELPBC can act as an inert scaffold for multivalent presentation of targeting ligands.

Next, we evaluated the effect of presentation of ligand to determine if multivalent presentation of the RGD ligand promotes receptor-mediated binding to. Prior to these experiments, we quantified integrin expression levels in K562 and K562/αvβ3 cell lines by antibody (Ab) staining with a fluorescently-labeled, αvβ3-specific Ab (LM609) and flow cytometry analysis (Sup. Fig. 1). This experiment revealed a bimodal distribution of integrin expression, with only ~60% of K562/αvβ3+ cells expressing the receptor. Interestingly, there was also low (~15%) αvβ3 expression on the receptor-negative K562 cells (Fig. 5a). These findings suggested that if the RGD-ELPBC specifically interacts with the αvβ3 integrin, then resulting histograms of the RGD-ELPBCs by receptor-positive K562/αvβ3 cells should mirror those observed for the LM609 antibody. Hence, K562/αvβ3 cells incubated with RGD-ELPBC at T > CMT should also show increased fluorescence with a bimodal distribution. In contrast, reflective of the low level of receptor expression by K562 cells, RGD-ELPBC interaction with the receptor negative K562 cell line should only show a slight (< 15%) increase at T > CMT as compared to T < CMT.

RGD-ELPBCs were next incubated with K562 and K562/αvβ3 cells at T < CMT and T > CMT for one hour. Each cell population was then monitored by flow cytometry to determine the effects of self-assembly and ligand-receptor interaction on cell binding/uptake. The resulting data show two interesting features. First, all RGD-ELPBCs led to a small increase in fluorescence intensity above the CMT as compared to the same ELP below the CMT in the receptor-negative K562 cell line (panels IV–VI, Fig. 3). Quantification of this effect showed that 5 – 15% of cells showed significantly higher fluorescence intensity following heating (Fig. 4a). This result is consistent with the finding that < 20% of the cells in the K562 cell line express the αvβ3 integrin and indicates that there is slightly enhanced interaction of RGD-ELPBC in its micellar state (T > CMT) compared to the monovalent state (T < CMT) by K562 (αvβ3−) cells.

Second, the histograms of the receptor-positive K562/αvβ3 cells incubated with RGD-ELPBCs (panels I–III, Fig. 3) were dramatically different based on the ELPBC SR. The fluorescence histogram of micellar RGD-ELP-96/60 by K562/αvβ3 cells was similar to wild-type K562 cells, illustrating that multivalent ligand presentation did not have an effect on cell receptor presentation for this ELPBC. In contrast, the RGD-ELP-64/60 and RGD-ELP-64/90 micelles (T > CMT) both exhibited a bimodal distribution of fluorescence, with ~50% of the K562/αvβ3 cells exhibiting a significant increase in fluorescence intensity relative to the same ELPs in unimer form (T < CMT)(Fig. 3). Confocal fluorescence microscopy of K562/αvβ3 cells incubated with RGD-ELPBCs confirmed these results (Fig. 5b). While K562/αvβ3 cells incubated with RGD-ELP-96/60 did not show significant interaction with ELP, cells incubated with RGD-ELP-64/60 or RGD-ELP-64/90 above their CMT showed a binary distribution with an approximately equal fraction of cells exhibiting high fluorescence and another population that exhibited virtually no fluorescence (Fig. 5b). These results clearly suggest that a threshold of SR is required, above which there is significant receptor-mediated interaction of the RGD-ELPBC with K562/αvβ3 cells.

In addition, there was a noticeable right-shift of the peak within the AlexaFluor488+ region of the flow cytometry histograms, representing a significant difference in the per-cell fluorescence intensity of cells targeted by RGD-ELP-64/90 and RGD-ELP-64/60 compared to RGD-ELP-96/60 (Fig. 3). Quantitative analysis of this shift showed a significant increase in the median fluorescence intensity of this peak with increasing SR of the ELPBC (Fig. 4b). The normalized intensity of this peak following incubation with RGD-ELP-64/90 was 5-fold greater at T > CMT than at T < CMT, while a 2-fold increase in the intensity of this peak was observed for RGD-ELP-64/60 at T > CMT relative to T < CMT. These results were visually confirmed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 5b). K562/αvβ3 cells incubated with RGD-ELP-64/90 at T > CMT showed greater fluorescence than RGD-ELP-64/60, which, in turn, showed greater fluorescence than RGD-ELP-96/60. These data clearly suggest that an increase in hydrophobic content of the RGD-ELPBC, as defined by their SR, enhances multivalent ligand-receptor interaction following micelle formation.

We further evaluated the importance of nanoscale architecture in controlling the receptor-mediated interaction of the RGD-terminated ELPBCs. To do so, we expressed an RGD-ELP-150, a homopolymer that exhibits inverse phase transition behavior. RGD-ELP-150 has approximately the same MW as the ELPBCs used in this study, but this ELP exhibits completely different temperature-dependent behavior at the same solution concentration as the ELPBC. RGD-ELP-150 is soluble at T < Tt and forms micron-sized aggregates at T > Tt as confirmed by DLS (Sup. Fig. 2). Because RGD-ELP-150 forms micron-sized aggregates rather than nanoscale micelles in the temperature range of interest (20 – 42 °C), it is useful for determining the importance of ligand presentation on a nanoscale scaffold as opposed to a polydisperse aggregate. We incubated RGD-ELP-150 with both K562 and K562/αvβ3 cells at T > Tt. The fraction of AlexaFluor488+ K562 and K562/αvβ3 cells following incubation at T > Tt was significantly smaller than K562/αvβ3 cells incubated with RGD-ELP-64/90 or RGD-ELP-64/60 (Fig. 5) above its CMT. These results indicate that multivalent presentation by a ordered nanoscale scaffold led to greater cell binding/uptake as compared to presentation of the same ligand by a large polydisperse aggregate, thus highlighting the importance of the nanoscale architecture of ligand presentation for multivalent targeting.

Discussion

The results presented herein demonstrate the feasibility of DAM by temperature-triggered self-assembly of a ligand-functionalized, genetically encoded diblock ELPBC. Our results show that multivalent presentation of the RGD peptide ligand by self-assembled RGD-ELPBC nanoparticles promotes significant binding of the polymer only to cells that overexpress the αvβ3 integrin.

In contrast, both receptor-positive and receptor-negative cell lines show low binding of RGD-ELPBC in its low affinity, monovalent state. Both cell lines also show low binding of ligand-negative ELPBC nanoparticles following their temperature-triggered self-assembly. Given that the cellular binding/uptake is only significantly greater for multivalent RGD-ELPBC constructs in receptor-positive cells as compared to all other negative controls, the cause for increased cellular interaction by RGD-ELPBC is likely caused by higher avidity of the multivalent RGD micelle compared to the lower affinity of the monovalent RGD-ELPBC. Our data further indicates that this multivalent presentation of the RGD ligand requires an ordered scaffold such as the ELPBC micelle, as polydisperse, micron-sized aggregates of RGD-ELP-150 did not show enhanced interaction above their Tt. These observations also suggest that that large fluorescence aggregates observed in the images of K562/αvβ3 are a result of integrin clusters in close proximity rather than aggregated ELP. 25

An interesting finding of this study was that RGD-ELPBCs with higher hydrophobic content (and hence a larger SR) are more avidly interact with cells that overexpress the αvβ3 receptor. This finding is notable as it suggests that subtle differences in the molecular architecture of a nanoscale ligand scaffold can have a large effect on receptor binding. To the best of our knowledge, the effect of this level of architectural control on ligand presentation has not been uncovered in previous studies of receptor-mediated binding by self-assembled polymeric micelles.

Although the origins of this behavior are not clear at this time, we believe that a likely explanation of binding dependence on SR is ligand-receptor accessibility. Although future study is needed to establish a definite mechanism, we believe that RGD-ELPBC micelles with larger hydrophobic cores may have subtle differences in the mobility of the terminal ligand that enable more effective presentation of multiple ligands to membrane-bound αvβ3 receptors. This hypothesis is consistent with our previous work showing different patterns of micelle formation that correlated with the SR of the ELPBC 10. We observed a decrease in the apparent stability of the nanoparticles with increased SR of the ELPBC as evidenced by the smaller temperature range over which monodisperse micelles is the predominant phase 10. The decrease in micelle stability, we suggest, may correlate with greater mobility within the corona of the micelle and thus greater simultaneous accessibility to different αvβ3 integrins. Additionally, multivalent interaction involving the αvβ3 integrin requires receptor clustering following integrin activation 20. ELP-64/90, which showed the greatest cellular interaction of the three ELPBCs studied herein, shows a steady increase in size with temperature. This may also facilitate cluster formation due to the greater probability of covering multiple integrins prior to clustering. While additional studies are needed to fully understand the reasons behind these differences in binding, there appears to be a clear effect of micelle architecture on its multivalent interaction with a specific cell surface receptor.

Finally, these biopolymers have other ancillary attributes that make them attractive for the targeted delivery of drugs and imaging agents. They can be readily overexpressed from a synthetic gene with a low-affinity peptide ligand appended at their hydrophilic terminus and unique reactive sites for conjugation of drugs or imaging agents at the hydrophobic end of the polymer, ensuring convenient synthesis. They are readily purified with sufficient yield and high purity by means of their phase transition behavior. The ELPBCs are also monodisperse and exhibit a precisely defined nanoscale architecture following self-assembly. Finally, the thermally triggered micelle self-assembly of these ELPBCs is retained in serum (Sup. Fig. 4), suggesting that these polymers will retain their targeting properties following systemic in vivo administration. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a rationally designed polymer that exhibits dynamic modulation of receptor binding affinity in response to an external trigger.

Although these results are promising for dynamic multivalent targeting, they represent only the first step towards translation of these findings into a nanoscale carrier that will have clinical utility to target specific tissue and organs. The first and outstanding challenge is to re-engineer the RGD-ELP-64/90, which exhibited the largest magnitude of DAM, to exhibit a CMT between 39 – 43 °C under physiological conditions, the current approved temperature range for mild hyperthermia. 26 RGD-ELP-64/90 shows self-assembly into nanoparticles in serum with a CMT of 33 °C (Sup. Fig. 3), which is 7 °C lower than the target CMT of 40 °C. We believe, based on our previous experience in designing ELPs, that moving the CMT of this ELPBC into the desired range for mild clinical hyperthermia should be possible by a subtle alteration of the guest residue composition of the hydrophobic block, without compromising its self-assembly or ligand presentation. The second challenge is to select a drug that does not perturb the self-assembly process. In this regard, we believe that a rational strategy is to match the hydrophobicity of the drug with that of the hydrophobic core. Future studies will focus on addressing these challenges to move DAM into a preclinical animal model.

Methods

Nomenclature

ELPs are described by the nomenclature ELP[VxAyGz]m, where m refers to the number of pentapeptide repeats and x, y, and z refer to the relative fraction of valine, alanine, and glycine in the guest residue position along the length of the protein, respectively. The number in the shorthand ELP description refers to the number of pentapeptide repeats in the particular segment. All block copolymers used in this study have the composition ELP[V1A8G7]/ELP[V5] and the homopolymer has the composition ELP[V5A2G3]. For example, the di-block copolymer ELP-64/90 consists of two blocks, the first is composed of 64 pentapeptides and the second of 90 pentapeptides. In contrast, the ELP-150 consists of 150 pentapeptides.

ELP Cloning and Expression

The ELP[V1A8G7]/ELP[V5] block copolymer gene and the ELP[V5A2G3] gene were synthesized using the recursive directional ligation method, described previously 7. Unmodified pET-25b plasmid was digested with EcoRI and NdeI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Synthetic oligonucleotides encoding the sense and antisense strands of the N-terminal leader and C-terminal trailer peptide sequences in the ELPs (IDT, Coralville, IA) were annealed to form a cassette with EcoRI- and NdeI-compatible ends. These cassettes were ligated into EcoRI/NdeI digested pET-25b and transformed into Top10™ competent cells (Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA) to create the modified pET-25bAS2 and pET-25bSV2 expression vectors (Sup. Fig. 4). Following confirmation by restriction digestion, the pET-25bAS2 and pET-25bSV2 vectors were digested with SfiI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and purified by gel purification, as above. The gene corresponding to ELP-64/90 was ligated into both modified pET-25b vectors and transformed into BLR competent cells (Novagen, Madison, WI). The insertion of the ELP-64/90 and ELP-150 genes into each vector was confirmed by gel electrophoresis of plasmids digested with XbaI and HindIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) followed by DNA sequencing.

ELP Purification

All ELPs used in this study were expressed by a hyperexpression protocol, as follows: BLR E. coli containing the ELP plasmid were grown overnight in a shaker incubator in 50 mL TB Dry media (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) and 1 mg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C and 270 rpm. The resulting cultures were centrifuged to collect the cells, and the cell pellet was resuspended and grown overnight in 1 L of TB Dry media with 1 mg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C and 270 rpm. The cells were harvested for the culture and lysed, and the ELP was then purified using the inverse transition cycling (ITC) purification method, as previously described12. Each ELP was purified from the soluble fraction of cell lysate by 5 rounds of ITC, then resuspended in PBS, and stored at −20 °C until further use.

Fluorophore Conjugation

1 mL of 200 µM ELP (all ELPs in this study) was pelleted by centrifugation at 16000 rcf at 50 °C, a temperature that is above the Tt of the ELP. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 900 µL conjugation buffer (0.1 M NaPO4, 3 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at room temperature. 1 mg of AlexaFluor488-C5 maleimide (AF488, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was then dissolved in 100 µL anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), immediately mixed with ELP/binding buffer solution, and continuously rotated at RT. The reaction was quenched after 2 hours and excess fluorophore was removed by one round of ITC and desalting via a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). The ELP-Alexa488 was concentrated to 1 mL total using the aforementioned ITC method and stored at −20 °C.

Dynamic Light Scattering

100 µL of 10 µM ELP in PBS was filtered using a 0.02 µm syringe filter (GE Healthcare) and 35 µL of the filtered solution were added to each well of a 384-well plate (Corning, Corning, NY). Small drops of mineral oil were added to the top of each well to prevent evaporation. The wells in the plate were analyzed using a thermally-controlled dynamic light scattering Wyatt Plate Reader (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). Ten acquisitions were obtained for each well in 1 °C increments from 20 – 45 °C. The resulting data was fit using a Rayleigh sphere model and either a regularization or cumulant algorithm based on the sum-of-squares value. Populations comprising less than 2% of the total mass were excluded from the analysis. This data was used to directly determine the average hydrodynamic ratio (Rh) and molecular weight (MW) of the particles in solution. The number of unimers per micelle, coordination number, was estimated by:

| (2) |

and ligand density was estimated by:

| (3) |

The critical micelle temperature (CMT) for each construct was defined as the first temperature where Rh is significantly greater than the average unimer Rh.

Thermal Characterization in Serum

The phase transition behavior of each ELP was characterized in serum by monitoring the absorbance of a 10 µM ELP in fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich) at 350 nm as a function of temperature (1 °C/min) on a UV-vis spectrophotometer equipped with a multicell thermoelectric temperature controller (Cary 300 Bio; Varian, Inc., Cary, NC). For ELPBCs, the CMT was defined as the temperature at which the optical density (OD) first increased from baseline.

Cell Culture

Both wild type human leukemia K562 cells, K562 (αvβ3−), and a stable variant transformed with the gene encoding αvβ3 integrin, K562/αvβ3(αvβ3+), were a generous gift from Dr. S. Blystone at Upstate Medical University 23. Both cell lines were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) (Invitrogen) or RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine and maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. K562-αvβ3 media also contained 500 µg/mL of G418 (Invitrogen). Flasks were started from frozen cell stocks. Cells were split once every 48 hours.

Receptor Expression

500,000 K562 or K562/αvβ3 cells were plated in 6-well plates and allowed to incubate overnight. Cells were visually inspected, rinsed twice, concentrated to 500 µL via centrifugation, and added to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube. 3 µg LM609 anti-αvβ3 Ab conjugated to AF488 (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was added to each tube, and cells were incubated at RT for 1 hour. Cells were then rinsed three times and analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 3).

Cell Uptake/Binding

500,000 K562 or K562/αvβ3 cells were plated in 6-well plates and allowed to incubate overnight. Cells were visually inspected, rinsed twice, and resuspended in 500 µL of a 10 µM ELP-AF488 cell suspension (HBSS, 1 mM CaCl2). Each sample was rotated at either room temperature or 40 °C in normal atmosphere for 1 hour and rinsed in binding buffer 3 times. Cells for flow cytometry analysis were fixed in 4% PFA for 15 minutes (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA) and stored at 4 °C (n = 3). Cells for confocal analysis were immediately mounted on slides and imaged using confocal microscopy.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Fixed cell samples were analyzed using a LSRII Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). All samples of fixed cells were analyzed within 18 hours of fixation. Viable cells were gated using the forward scatter and side scatter plots of an unstained control sample. A minimum of 10,000 live cells were analyzed per sample. For Ab characterization, cells with intensity 2 standard deviations (SD) over the median intensity of unlabeled control cells were defined as receptor-positive. For binding/uptake experiments, heated cells with intensity 2 SD over the intensity of unheated cells were defined as ELP-positive. Fold-increase in median fluorescence intensity was obtained by dividing the corrected median fluorescence intensity of the AF+ region of the heated sample by the corrected median fluorescence of the unheated sample with otherwise identical conditions.

Confocal Imaging

5 µL of unfixed cell sample was mixed with a small volume of Fluoromount-G (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and placed on a glass slide. Samples were then mounted and sealed. Slides were then immediately imaged at 5× and 20× using an LSM5 Pascal confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkotchen, Germany) with 2 channels for differential interference contrast (DIC) and AlexaFluor488. All images were obtained within 2 hours of slide mounting. Confocal images were not used for quantitative analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Jonathan McDaniel for the TOC graphic. This research was supported by the NIH though a grant (R01 EB-007205) to A.C. and by a NSF IGERT fellowship to A.S. (DGE-0221632, PI: Clark).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and additional figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Ehrlich P. Collected Studies on Immunity. 1906 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams GP, Schier R, McCall AM, Simmons HH, Horak EM, Alpaugh RK, Marks JD, Weiner LM. High Affinity Restricts the Localization and Tumor Penetration of Single-Chain Fv Antibody Molecules. Cancer Res. 2001;(12):4750–4755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan MR, Rosca EV. Targeting Drugs to Combinations of Receptors: A Modeling Analysis of Potential Specificity. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;(8):1113–1124. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-5779-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mauriz JL, Gonzalez-Gallego J. Antiangiogenic Drugs: Current Knowledge and New Approaches to Cancer Therapy. J Pharm Sci. 2008;(10):4129–4154. doi: 10.1002/jps.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mammen M, Choi SK, Whitesides GM. Polyvalent Interactions in Biological Systems: Implications for Design and Use of Multivalent Ligands and Inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1998;(20):2754–2974. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nanocarriers as an Emerging Platform for Cancer Therapy. Nat Nanotech. 2007;(12):751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Genetically Encoded Synthesis of Protein-Based Polymers with Precisely Specified Molecular Weight and Sequence by Recursive Directional Ligation: Examples from the Elastin-Like Polypeptide System. Biomacromolecules. 2002;(2):357–367. doi: 10.1021/bm015630n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urry DW. Free Energy Transduction in Polypeptides and Proteins Based on Inverse Temperature Transitions. Prog Biophys Mol Bio. 1992;(1):23–57. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(92)90003-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urry DW. Physical Chemistry of Biological Free Energy Transduction as Demonstrated by Elastic Protein-Based Polymers†. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1997;(51):11007–11028. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreher MR, Simnick AJ, Fischer K, Smith RJ, Patel A, Schmidt M, Chilkoti A. Temperature Triggered Self-Assembly of Polypeptides into Multivalent Spherical Micelles. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;(2):687–694. doi: 10.1021/ja0764862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee TAT, Cooper AARP, Conticello VP. Thermo-Reversible Self-Assembly of Nanoparticles Derived from Elastin-Mimetic Polypeptides. Adv Mater. 2000;(15):1105–1110. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Purification of Recombinant Proteins by Fusion with Thermally-Responsive Polypeptides. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;(11):1112–1115. doi: 10.1038/15100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koivunen E, Gay DA, Ruoslahti E. Selection of Peptides Binding to the A5β1 Integrin from Phage Display Library. J Biol Chem. 1993;(27):20205–20210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gladson CL, Cheresh DA. Glioblastoma Expression of Vitronectin and the Avβ3 Integrin. Adhesion Mechanism for Transformed Glial Cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;(6):1924–1932. doi: 10.1172/JCI115516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Max R, Roland RC, Gerritsen M, Peet TG, Nooijen A, Goodman SL, Sutter A, Keilholz U, Ruiter DJ, De Waal RMW. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Integrin Avβ3 Expression on Tumor-Associated Vessels of Human Carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1997;(3):320–324. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970502)71:3<320::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindemann S, Kramer B, Seizer P, Gawaz M. Platelets, Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;(1):203–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winter PM, Morawski AM, Caruthers SD, Fuhrhop RW, Zhang H, Williams TA, Allen JS, Lacy EK, Robertson JD, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Molecular Imaging of Angiogenesis in Early-Stage Atherosclerosis with Avβ3-Integrin-Targeted Nanoparticles. Circulation. 2003;(18):2270–2274. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000093185.16083.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vagnucci AH, Li WW. Alzheimer's Disease and Angiogenesis. The Lancet. 2003;(9357):605–608. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruoslahti E. Rgd and Other Recognition Sequences for Integrins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Bi. 1996;(1):697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin Signaling. Science. 1999;(5430):1028–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreher MR, Raucher D, Balu N, Michael Colvin O, Ludeman SM, Chilkoti A. Evaluation of an Elastin-Like Polypeptide-Doxorubicin Conjugate for Cancer Therapy. Journal of Controlled Release. 2003;(1–2):31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maheshwari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell Adhesion and Motility Depend on Nanoscale Rgd Clustering. J Cell Sci. 2000;(10):1677–1686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blystone SD, Graham IL, Lindberg FP, Brown EJ. Integrin Avβ3 Differentially Regulates Adhesive and Phagocytic Functions of the Fibronectin Receptor A5β1. J Cell Biol. 1994;(4):1129–1137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.4.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raucher D, Chilkoti A. Enhanced Uptake of a Thermally Responsive Polypeptide by Tumor Cells in Response to Its Hyperthermia-Mediated Phase Transition. Cancer Res. 2001;(19):7163–7170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maheshwari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell Adhesion and Motility Depend on Nanoscale Rgd Clustering. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;(10):1677–1686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urano M. Invited Review: For the Clinical Application of Thermochemotherapy Given at Mild Temperatures. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 1999;(2):79–107. doi: 10.1080/026567399285765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.