Abstract

Objective To determine whether a nurse led smoking cessation intervention affects smoking cessation rates in patients admitted for coronary heart disease.

Design Randomised controlled trial.

Setting Cardiac ward of a general hospital, Norway.

Participants 240 smokers aged under 76 years admitted for myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or cardiac bypass surgery. 118 were randomly assigned to the intervention and 122 to usual care (control group).

Intervention The intervention was based on a booklet and focused on fear arousal and prevention of relapses. The intervention was delivered by cardiac nurses without special training. The intervention was initiated in hospital, and the participants were contacted regularly for at least five months.

Main outcome measure Smoking cessation rates at 12 months determined by self report and biochemical verification.

Results 12 months after admission to hospital, 57% (n = 57/100) of patients in the intervention group and 37% (n = 44/118) in the control group had quit smoking (absolute risk reduction 20%, 95% confidence interval 6% to 33%). The number needed to treat to get one additional person who would quit was 5 (95% confidence interval, 3 to 16). Assuming all dropouts relapsed at 12 months, the smoking cessation rates were 50% in the intervention group and 37% in the control group (absolute risk reduction 13%, 0% to 26%).

Conclusion A smoking cessation programme delivered by cardiac nurses without special training, significantly reduced smoking rates in patients 12 months after admission to hospital for coronary heart disease.

Introduction

Smoking cessation after myocardial infarction is associated with a 50% reduction in mortality after three to five years.1 Reduced mortality is apparent after a few months and increases with time.2 After a coronary event, 30-45% of patients stop smoking spontaneously.3,4 Randomised investigations of smoking cessation after admission to hospital for coronary heart disease have obtained mixed results.4-16 Studies of interventions to change lifestyle, where helping patients to quit smoking was only part of the intervention, have not shown any statistically significant effects on smoking cessation rates.5-9 In studies addressing only smoking cessation, those with brief interventions have been ineffective.4,10,11 Three of five trials with longer interventions (4-6 months) have shown increased smoking cessation rates.12-16 Only one of these, however, verified that patients had quit smoking by biochemical means.12

Fear arousal messages are important in smoking cessation.16,17 We aimed to determine whether a nurse led smoking cessation intervention with emphasis on fear arousal affected smoking cessation rates after 12 months among patients admitted for coronary heart disease.

Methods

We invited to participate in our study all patients admitted to Vest-Agder Hospital, Kristiansand, Norway for myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or care after coronary bypass surgery performed at other hospitals. Eligible patients had to be under 76 years of age and daily smokers. We excluded patients with serious illnesses associated with short life expectancies (cancer, chronic obstructive lung disease, renal or liver failure), serious psychiatric problems, alcoholism, and dementia.

The nurses recruited patients two to four days after admission. Participants were randomly allocated to usual care (control group) or intervention. Doctors were not involved in the programme.

Control and intervention groups

Patients were offered group sessions twice a week with the nurses, in which the importance of smoking cessation was mentioned. Sometime during these sessions a video was shown and a booklet handed out, which contained general information on coronary heart disease and advice on quitting smoking. The control group received no further specific instructions on how to stop smoking.

One of three nurses consulted the patients once or twice during their hospital stay. The intervention was based on a 17 page booklet specially produced for the trial. This booklet emphasised the health benefits of quitting smoking after a coronary event. Two illustrations showed the differences in mortality between those who continued smoking after myocardial infarction or unstable angina and those who stopped. One of the illustrations was a bar chart showing a 60% risk reduction for death after five years of quitting, and the other was a linear chart showing that after 13 years 18% of patients who continued smoking were alive compared with 63% of those who had quit.2 On the basis of these figures, the participants were told that they most probably would have another heart attack if they continued smoking (fear arousal message).

The booklet also contained information on how to prevent relapse, how to stop smoking for those who had not stopped or had relapsed, and how to use nicotine replacements. Also explained was how to identify and cope with high risk situations for relapse, with action plans.

The patients were advised not to smoke during their hospital stay. Those with strong withdrawal urges were encouraged to use nicotine replacements (gum or patch). Spouses who smoked were also asked to quit.

The nurses contacted participants by telephone two days, one week, three weeks, three months, and five months after discharge. At six weeks all participants in the intervention group had a consultation at the outpatient clinic with one of the cardiac nurses. The outpatient contacts included prevention of relapses and positive feedback (for example, telling patients who were still not smoking that they already had less chance of another heart attack). The health benefits of quitting were repeated and, if necessary, a fear arousal message given. Those who continued smoking or relapsed were offered additional support and advice.

Outcome measures

The patients were asked to return after 12 months. Smokers who stated that they were still smoking were classified as smokers and those who claimed they had quit and had a nicotine metabolite concentration < 2.0 mmol/mol creatinine in urine were classified as non-smokers.

Results

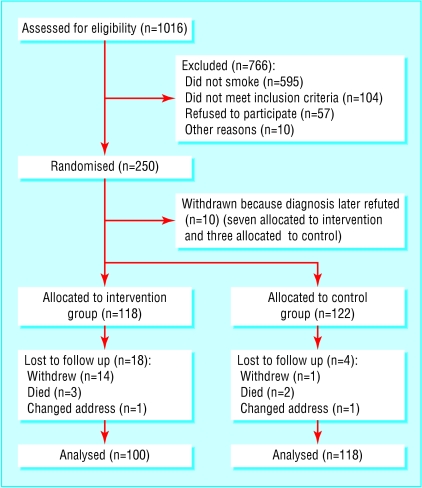

Patients were recruited from February 1999 to September 2001 (figure). Education and working status differed slightly between the two groups at baseline (table).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through trial

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with coronary heart disease assigned to smoking cessation programme or usual care (control group). Values are numbers (percentages) of patients unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Intervention group (n=118) | Control group (n=122) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 57 (9) | 57 (9) |

| Men | 90 (76) | 92 (75) |

| Married or living with partner | 90 (76) | 94 (77) |

| Employed | 67 (57) | 52 (43) |

| No education after primary school | 46 (39) | 33 (27) |

| Retired | 21 (18) | 35 (29) |

| Alcohol consumption >1 unit a day | 5 (4) | 8 (7) |

| Previously no coronary artery disease | 93 (79) | 85 (70) |

| Myocardial infarction | 91 (77) | 85 (69) |

| Bypass surgery | 10 (8) | 18 (15) |

| Unstable angina | 17 (14) | 19 (16) |

| Mean (SD) No of days in hospital | 6.9 (4.4) | 6.7 (3.4) |

| Mean (SD) No of days in intensive care unit | 2.7 (2.0) | 2.8 (2.1) |

| Mean (SD) years of smoking | 38.3 (13.9) | 37.6 (11.5) |

| Mean (SD) No of cigarettes a day | 14.3 (5.7) | 15.6 (8.3) |

| Mean (SD) No of previous attempts to quit | 2.3 (3.1) | 2.3 (3.0) |

| Smoked in 24 hours before admission | 101 (87) | 114 (93) |

| Spouse who smokes | 45 (38) | 51 (42) |

Patients in the intervention group had an average of 1.6 (SD 0.7) consultations as inpatients and 1.6 (SD 1.5) as outpatients. They also received a mean of 8.5 (SD 3.2) telephone calls. Most patients (85%) received more telephone calls than the intended minimum of five. The mean total time devoted to each patient was 147 minutes (SD 50), including time to fill in questionnaires. Thirty six per cent (36/100) of the participants in the intervention group and 28% (33/118) in the control group used nicotine replacements (without a statistically significant difference).

Smoking cessation rates

Six of the patients who stated that they were non-smokers at 12 months had nicotine metabolite concentrations above the reference limit (three in each group), and three refused to provide a urine sample (one in the intervention group and two in the control group). All these patients were classified as smokers. The validated smoking cessation rates at 12 months were therefore 57% (57/100) in the intervention group and 37% (44/118) in the control group (absolute risk reduction 20%, 95% confidence interval 6% to 33%). The number needed to treat to get one additional patient to quit was 5 (3 to 16). The groups showed similar smoking cessation rates while in hospital and at six weeks' follow up (see bmj.com). No biochemical validations were made at this stage.

What is already known on this topic

Stopping smoking after a coronary event decreases mortality substantially

Around 60-70% of smokers who survive a coronary event return to regular smoking within a year

Smoking cessation programmes of short duration are ineffective in preventing patients with cardiac disease from relapsing

What this study adds

A smoking cessation programme delivered individually and regularly for several months by nurses was effective among smokers admitted for coronary heart disease

A long intervention period seems to be important

Of the 22 patients lost to follow up, seven died or changed address. Seven of the remaining 15 said they were non-smokers (not validated biochemically) and seven said they were smokers at the time of withdrawal. Assuming that these 15 patients returned to smoking at 12 months, in an intention to treat analysis the smoking cessation rates were 50% (57/114) in the intervention group and 37% (44/119) in the control group (absolute risk reduction 13%, 0% to 26%, number needed to treat 8, 4 to 250).

Predictors of outcome

In a multiple logistic regression analysis of predictors of abstinence, the intervention versus control group (odds ratio 1.93, 1.07 to 3.46) and absence versus occurrence of previous coronary heart disease (2.60, 1.18 to 5.71) showed statistically significant positive associations with cessation (see also bmj.com).

Only 9% (7/80) of the patients who smoked while in hospital or at six weeks' follow up were abstinent at 12 months (three in the intervention group and four in the control group).

Discussion

A nurse led smoking cessation intervention with at least five months' follow up increased smoking cessation rates among patients admitted to hospital for coronary heart disease. Further intervention had little impact in those patients who smoked while in hospital or at six weeks' follow up. Since there were no differences in smoking cessation rates between the groups at six weeks, we speculate that a long intervention period was an important factor. It is also possible that the initial intervention provided such a strong motivation for abstinence that it prevented later relapses.

Our dropout rate of less than 10% was lower than in comparable studies.12-14 Only one patient in the control group, excluding those who died or changed address, was lost to follow up. The dropout rate in the intervention group was higher than in the control group. This may have been a result of the intervention itself.

We believe that our study is the largest to date addressing only smoking cessation, with a long intervention period. The applicability of the results was strengthened by the low dropout rate and by the inclusion of most patients who smoked, regardless of previous coronary heart disease. Further, the principles of the intervention, focusing on fear arousal and relapse prevention, were simple. Assuming a time commitment of 2.4 hours for each patient, a nurse working part time has the capacity to conduct individual smoking cessation programmes on eight patients a week. This intervention is probably cost effective compared with other medical treatments in preventing cardiac events and deaths, and we suggest that similar programmes should be provided as part of routine care in wards dealing with cardiac conditions.

This is an abridged version; the full version is on bmj.com

This is an abridged version; the full version is on bmj.com

We thank the cardiac nurses Tone Baeck, Eva Boroey, and Anne Kari Kjellesvik for delivering the intervention and collecting data.

Contributors: See bmj.com

Funding: Vest-Agder Council for Public Health and the charity Sykehuset i vaare hender.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the regional ethics committee.

References

- 1.Wilson K, Gibson N, Willan A, Cook D. Effect of smoking cessation on mortality after myocardial infarction: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Arch Intern Med 2000;160: 939-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daly LE, Mulcahy R, Graham IM, Hickey N. Long term effect on mortality of stopping smoking after unstable angina and myocardial infarction. BMJ 1983;287: 324-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigotti NA, Singer DE, Mulley AG Jr, Thibault GE. Smoking cessation following admission to a coronary care unit. J Gen Intern Med 1991;6: 305-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rigotti NA, McKool KM, Shiffman S. Predictors of smoking cessation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Results of a randomized trial with 5-year follow-up. Ann Intern Med 1994;120: 287-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Superko HR, Dennis CA, Thomas RJ, Lew HT, et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 1994;120: 721-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Elderen-van Kemenade T, Maes S, van den Broek Y. Effects of a health education programme with telephone follow-up during cardiac rehabilitation. Br J Clin Psychol 1994;33: 367-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jolly K, Bradley F, Sharp S, Smith H, Thompson S, Kinmonth AL, et al. Randomised controlled trial of follow up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction and angina: final results of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). The SHIP Collaborative Group. BMJ 1999;318: 706-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Thain J, Deans HG, Rawles JM, Squair JL. Secondary prevention in coronary heart disease: a randomised trial of nurse led clinics in primary care. BMJ 2002;324: 87-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson R, Lindberg G, Westin L, Israelsson B. Influence of coronary nursing management follow up on lifestyle after acute myocardial infarction. Heart 1997;77: 256-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hajek P, Taylor TZ, Mills P. Brief intervention during hospital admission to help patients to give up smoking after myocardial infarction and bypass surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;324: 87-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreno Ortigosa A, Ochoa Gomez FJ, Ramalle-Gomara E, Saralegui Reta I, Fernandez Esteban MV, Quintana Diaz M. Efficacy of an intervention in smoking cessation in patients with myocardial infarction. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;114: 209-10. (In Spanish.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor CB, Houston-Miller N, Killen JD, DeBusk RF. Smoking cessation after acute myocardial infarction: effects of a nurse-managed intervention. Ann Intern Med 1990;113: 118-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dornelas EA, Sampson RA, Gray JF, Waters D, Thompson PD. A randomized controlled trial of smoking cessation counselling after myocardial infarction. Prev Med 2000;30: 261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor CB, Houston-Miller N, Haskell WL, DeBusk RF. Smoking cessation after acute myocardial infarction: the effects of exercise training. Addict Behav 1988;13: 331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ockene J, Kristeller JL, Goldberg R, Ockene I, Merriam P, Barrett S, et al. Smoking cessation and severity of disease: the coronary artery smoking intervention study. Health Psychol 1992;11: 119-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burt A, Thornley P, Illingworth D, White P, Shaw TR, Turner R. Stopping smoking after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1974;1: 304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perkins KA, Scott RR. A low-cost environmental intervention for reducing smoking among cardiac inpatients. Int J Addict 1986;21: 1173-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]