Abstract

Drought poses a serious threat to the sustainability of rice (Oryza sativa) yields in rain-fed agriculture. Here, we report the results of a functional genomics approach that identified a rice NAC (an acronym for NAM [No Apical Meristem], ATAF1-2, and CUC2 [Cup-Shaped Cotyledon]) domain gene, OsNAC10, which improved performance of transgenic rice plants under field drought conditions. Of the 140 OsNAC genes predicted in rice, 18 were identified to be induced by stress conditions. Phylogenic analysis of the 18 OsNAC genes revealed the presence of three subgroups with distinct signature motifs. A group of OsNAC genes were prescreened for enhanced stress tolerance when overexpressed in rice. OsNAC10, one of the effective members selected from prescreening, is expressed predominantly in roots and panicles and induced by drought, high salinity, and abscisic acid. Overexpression of OsNAC10 in rice under the control of the constitutive promoter GOS2 and the root-specific promoter RCc3 increased the plant tolerance to drought, high salinity, and low temperature at the vegetative stage. More importantly, the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants showed significantly enhanced drought tolerance at the reproductive stage, increasing grain yield by 25% to 42% and by 5% to 14% over controls in the field under drought and normal conditions, respectively. Grain yield of GOS2:OsNAC10 plants in the field, in contrast, remained similar to that of controls under both normal and drought conditions. These differences in performance under field drought conditions reflect the differences in expression of OsNAC10-dependent target genes in roots as well as in leaves of the two transgenic plants, as revealed by microarray analyses. Root diameter of the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants was thicker by 1.25-fold than that of the GOS2:OsNAC10 and nontransgenic plants due to the enlarged stele, cortex, and epidermis. Overall, our results demonstrated that root-specific overexpression of OsNAC10 enlarges roots, enhancing drought tolerance of transgenic plants, which increases grain yield significantly under field drought conditions.

Plants respond and adapt to abiotic stresses to survive under adverse conditions. Upon exposure of plants to such stresses, many genes are induced, and their products are involved in the protection of cellular machinery from stress-induced damage (Bray, 1993; Thomashow, 1999; Shinozaki et al., 2003). The expression of stress-related genes is largely regulated by specific transcription factors. The overexpression of such transcription factor genes often results in activation of many functional genes related to the particular stress conditions, consequently conferring stress tolerance. For example, the DREB1A/CBF3 gene in transgenic Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) activates expression of its stress-related downstream genes, thereby enhancing stress tolerance (Liu et al., 1998; Kasuga et al., 1999).

The rice (Oryza sativa) and Arabidopsis genomes each encode more than 1,300 transcriptional regulators, which account for 6% of the estimated total number of genes in each plant. About 45% of these transcription factors are reported to be from gene families specific to plants (Riechmann et al., 2000; Kikuchi et al., 2003). One example of such a plant-specific family of transcription factors is the NACs. The NAC acronym is derived from the names of the three genes that were first described as containing a NAC domain, namely NAM (for No Apical Meristem), ATAF1-2, and CUC2 (for Cup-Shaped Cotyledon). The NAC domain is a highly conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain, and NAC proteins also contain a variable C-terminal domain (Ooka et al., 2003; Jeong et al., 2009) and appear to be widespread in plants. The genomes of rice and Arabidopsis were initially predicted to contain 105 and 75 NAC genes, respectively (Ooka et al., 2003; Xiong et al., 2005). Later, 140 NAC genes were identified in rice (Fang et al., 2008). However, only a few of these genes have been characterized so far, and these show diverse functions in both plant development and stress responses. The earliest reported NAC genes include NAM from petunia (Petunia hybrida) that determines the position of the shoot apical meristem (Souer et al., 1996) and CUC2 from Arabidopsis that participates in the development of embryos and flowers (Aida et al., 1997). In addition, the Arabidopsis NAP gene regulates cell division and cell expansion in flower organs (Sablowski and Meyerowitz, 1998) and the AtNAC1 gene mediates auxin signaling to promote lateral root development (Xie et al., 2000). Genes in the ATAF subfamily, including StNAC (Collinge and Boller, 2001) from potato (Solanum tuberosum) and ATAF1-2 (Aida et al., 1997) from Arabidopsis, are induced by pathogen attack and wounding. More recently, AtNAC072 (RD29), AtNAC019, AtNAC055, and ANAC102 from Arabidopsis (Fujita et al., 2004; Tran et al., 2004; Christianson et al., 2009), BnNAC from Brassica napus (Hegedus et al., 2003), and SNAC1 and SNAC2 from rice (Hu et al., 2006, 2008) have been found to be involved in responses to various environmental stresses. AtNAC2, another stress-related NAC gene in Arabidopsis, functions downstream of the ethylene and auxin signal pathways and enhances salt tolerance when overexpressed (He et al., 2005). A wheat (Triticum aestivum) NAC gene, NAM-B1, has been reported to be involved in nutrient remobilization from leaves to developing grains (Uaury et al., 2006).

Drought is one of the major constraints to rice production worldwide. In particular, exposure to drought conditions during the panicle development stage results in a delayed flowering time, reduced number of spikelets, and poor grain filling. To date, a number of studies have suggested that the overexpression of stress-related genes may improve drought tolerance in rice to some extent (Xu et al., 1996; Garg et al., 2002; Jang et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2006, 2008; Ito et al., 2006; Nakashima et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2007). However, despite a number of such efforts to develop drought-tolerant rice plants, very few have shown an improvement in grain yields under field conditions. These include transgenic rice plants expressing SNAC1 (Hu et al., 2006), OsLEA3 (Xiao et al., 2007), and AP37 (Oh et al., 2009).

In this study, a genome-wide analysis of rice NAC transcription factors was conducted to identify genes that improve tolerance to environmental stress. A group of OsNAC genes were prescreened for enhanced stress tolerance when overexpressed in rice. Here, we report the role of OsNAC10, one of the effective members selected from the prescreening, in drought tolerance. Overexpression of OsNAC10 under the control of GOS2 (de Pater et al., 1992), a constitutive promoter, and RCc3 (Xu et al., 1995), a root-specific promoter, improved plant tolerance of transgenic rice to drought, high salinity, and low temperature during the vegetative stage of growth. In addition, RCc3:OsNAC10 plants showed significantly enhanced drought tolerance at the reproductive stage, with a grain yield increase of 25% to 42% over the controls under field drought conditions. Grain yield of GOS2:OsNAC10 plants under the same conditions, in contrast, remained relatively unchanged, demonstrating the potential use of the root-specific expression strategy for improving drought tolerance in rice.

RESULTS

Identification of Stress-Inducible Rice NAC Domain Genes

Previously, the rice genome was predicted to contain 140 OsNAC genes (Fang et al., 2008). To identify those that are stress inducible, we performed expression profiling with the Rice 3′-Tiling microarray (GreenGene Biotech). We obtained RNAs from the leaves of 14-d-old rice seedlings that had been subjected to drought, high salinity, abscisic acid (ABA), and low temperature. When three replicates were averaged and compared with untreated leaves, a total of 18 OsNAC genes were found to be up-regulated by 1.9-fold or greater (P < 0.05) upon exposure to one or more stress conditions (Table I). Phylogenic analysis of the amino acid sequences of the corresponding 18 OsNAC proteins revealed the presence of three subgroups (I–III; Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1). Furthermore, comparison of the amino acid sequences spanning the NAC domains in these proteins revealed signature motifs by which these subgroups can be distinguished (Fig. 1). For example, signature motifs Ia-c and IIa-c are specific to subgroups I and II, respectively. In addition to sequence similarities, the members of each subgroup were found to be closely related in terms of their response to stress. For example, the expression of the genes in subgroups II and III is not induced by low temperature.

Table I. Rice NAC transcription factor genes are up-regulated under stress conditions.

Numbers in boldface indicate up-regulation by more than 1.9-fold (P < 0.05) in plants grown under stress conditions. Accession numbers are as follows: SNAC1, AK067690; OsNAC6, AK068392; OsNAC5, AK102475.

| Subgroup | Sequence IDa | High Salinity |

Drought |

ABA |

Low Temperature |

||||

| Meanb | Pc | Meanb | Pc | Meanb | Pc | Meanb | Pc | ||

| I | OsNAC10 | 16.22 | 0.000 | 14.91 | 0.000 | 13.81 | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.788 |

| SNAC1 | 17.31 | 0.000 | 17.18 | 0.000 | 1.90 | 0.013 | 6.96 | 0.000 | |

| OsNAC6 | 5.94 | 0.000 | 5.16 | 0.000 | 4.62 | 0.000 | 2.80 | 0.011 | |

| OsNAC5 | 6.74 | 0.000 | 7.10 | 0.000 | 1.39 | 0.190 | 0.72 | 0.268 | |

| Os07g0683200 | 11.26 | 0.000 | 1.14 | 0.709 | 6.00 | 0.001 | 0.69 | 0.415 | |

| Os01g0816100 | 5.36 | 0.001 | 3.24 | 0.004 | 2.23 | 0.041 | 5.35 | 0.007 | |

| Os12g0123700 | 15.72 | 0.000 | 11.70 | 0.000 | 15.18 | 0.000 | 0.75 | 0.359 | |

| Os01g0862800 | 2.77 | 0.010 | 4.51 | 0.001 | 1.20 | 0.700 | 2.77 | 0.046 | |

| II | Os08g0115800 | 1.62 | 0.198 | 2.50 | 0.014 | 1.08 | 0.891 | 1.34 | 0.552 |

| Os09g0497900 | 2.34 | 0.003 | 2.12 | 0.003 | 1.03 | 0.927 | 0.65 | 0.146 | |

| Os12g0610600 | 1.54 | 0.104 | 0.45 | 0.006 | 4.84 | 0.000 | 0.61 | 0.153 | |

| Os06g0675600 | 2.92 | 0.002 | 1.29 | 0.313 | 3.45 | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.112 | |

| Os07g0684800 | 17.29 | 0.000 | 11.01 | 0.000 | 8.33 | 0.000 | 0.67 | 0.401 | |

| Os03g0327100 | 6.20 | 0.000 | 9.44 | 0.000 | 2.25 | 0.012 | 1.53 | 0.224 | |

| Os04g0460600 | 0.65 | 0.199 | 0.53 | 0.044 | 2.10 | 0.045 | 1.12 | 0.822 | |

| Os02g0579000 | 2.71 | 0.002 | 1.56 | 0.051 | 2.14 | 0.009 | 1.07 | 0.848 | |

| III | Os02g0555300 | 24.78 | 0.000 | 2.69 | 0.008 | 36.66 | 0.000 | 1.06 | 0.923 |

| Os04g0437000 | 3.40 | 0.001 | 1.39 | 0.149 | 4.16 | 0.000 | 1.04 | 0.926 | |

Sequence identification numbers for the full-length cDNA sequences of the corresponding genes.

The mean of three independent biological replicates. These microarray data sets can be found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (Gene Expression Omnibus).

P values were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Figure 1.

Alignments of NAC domain sequences from 18 stress-inducible rice genes. The deduced amino acid sequences of the NAC domains from these 18 genes (Table I) were aligned using the ClustalW program. Identical and conserved residues are highlighted (gray). Signature motifs are indicated by the boxes: Ia to Ic and IIa to IIc for subgroups I and II, respectively.

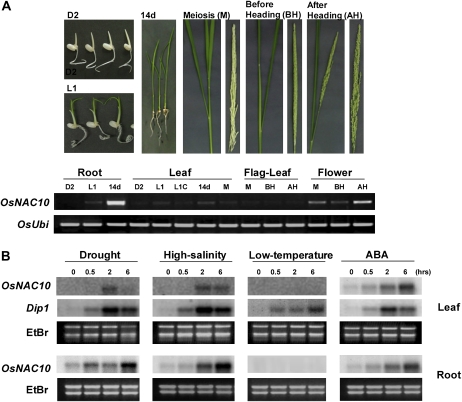

One of the stress-responsive OsNAC genes, OsNAC10 (AK069257), which is in subgroup I, was functionally characterized in this study. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis of this gene in various tissues at different stages of development revealed that it is predominantly expressed in roots and flowers (panicles; Fig. 2A). We also performed RNA gel-blot analysis using total RNAs from leaf tissues of 14-d-old seedlings exposed to high salinity, drought, ABA, and low temperature (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the results from our microarray experiments, the expression of OsNAC10 was induced by drought, high salinity, and ABA but not by low temperature.

Figure 2.

Expression of OsNAC10 in rice under different stress conditions and in various tissues at different developmental stages. A, Rice seeds were germinated and grown on MS agar medium in the dark for 2 d (D2) and then in the light for 1 d at 28°C (L1). The seedlings were transplanted into soil pots and grown in the greenhouse for 14 d (14d), until meiosis (M), until just before heading (BH), and until right after heading (AH). L1C, Coleoptiles from L1 seedlings. RT-PCR analyses were performed using RNAs from the indicated tissues at the indicated stages of development and gene-specific primers. The expression levels of a rice ubiquitin (OsUbi) were used as an internal control. B, Ten micrograms of total RNA was prepared from the leaf and root tissues of 14-d-old seedlings exposed to drought, high salinity, ABA, or low temperature for the indicated time periods. For drought stress, the seedlings were air dried at 28°C; for high-salinity stress, seedlings were exposed to 400 mm NaCl at 28°C; for low-temperature stress, seedlings were exposed to 4°C; for ABA treatment, seedlings were exposed to a solution containing 100 μm ABA. Total RNAs were blotted and hybridized with OsNAC10 gene-specific probes. The blots were then reprobed with the Dip1 gene, which was used as a marker for the up-regulation of key genes following stress treatments. Ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining was used to determine equal loading of RNAs.

Stress Tolerance of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 Plants at the Vegetative Stage

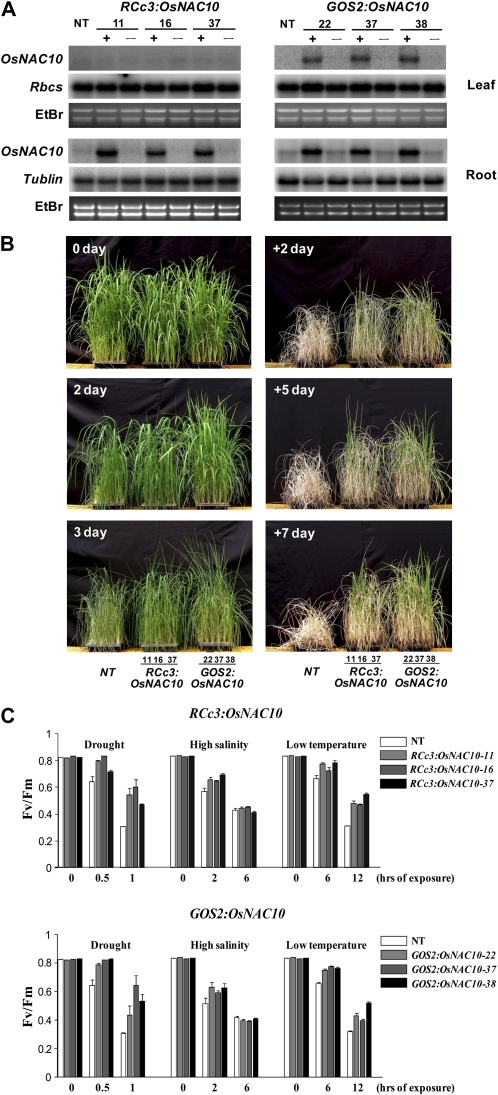

To enable the overexpression of the OsNAC10 genes in rice, their full-length cDNAs were isolated and linked to the RCc3 promoter (Xu et al., 1995) for root-specific expression and to the GOS2 promoter (de Pater et al., 1992) for constitutive expression, thereby generating the constructs RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10. These constructs were introduced into rice using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation (Hiei et al., 1994), which yielded 15 to 20 independent transgenic lines per construct. Transgenic T1 to T5 seeds were collected, and three independent T4 homozygous lines of both RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants were selected for further analysis. All of the transgenic lines grew normally with no stunting. The transcript levels of OsNAC10 in the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants were determined by RNA gel-blot analysis. For this purpose, total RNAs were extracted from leaf and root tissues of 14-d-old seedlings grown under normal growth conditions (Fig. 3A). OsNAC10 expression was clearly detectable in all of the transgenic lines but not in the nontransgenic (NT) controls. The transgenes were expressed at high levels in both the leaves and roots of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants but in the roots only of the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants, thus verifying the constitutive and root-specific nature of the respective promoters.

Figure 3.

Stress tolerance in vegetative stage RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. A, RNA gel-blot analyses were performed using total RNA preparations from the roots and leaves of three homozygous T4 lines of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, respectively, and of NT control plants. The blots were hybridized with OsNAC10 gene-specific probes and also reprobed for RbcS and Tubulin. Ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining was used to determine equal loading of RNAs. – indicates nullizygous (without transgene) lines, and + indicates transgenic lines. B, The appearance of transgenic plants during drought stress. Three independent homozygous T4 lines of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants and NT controls were grown for 4 weeks, subjected to 3 d of drought stress, and followed by 7 d of rewatering in the greenhouse. Photographs were taken at the indicated time points. + denotes the number of rewatering days under normal growth conditions. C, Changes in the chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) of rice plants under drought, high-salinity, and low-temperature stress conditions. Three independent homozygous T4 lines of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants and NT controls grown in MS medium for 14 d were subjected to various stress conditions as described in “Materials and Methods.” After these stress treatments, the Fv/Fm values were measured using a pulse modulation fluorometer (mini-PAM; Walz). All plants were grown under continuous light of 150 μmol m−2 s−1 prior to stress treatments. Each data point represents the mean ± se of triplicate experiments (n = 10).

To investigate whether the overexpression of OsNAC10 correlated with stress tolerance in rice, 4-week-old transgenic plants and NT controls were exposed to drought stress (Fig. 3B). The NT plants started to show visual symptoms of drought-induced damage, such as leaf rolling and wilting with a concomitant loss of chlorophylls, at an earlier stage than the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. The transgenic plants also recovered more quickly than the NT plants upon rewatering. Consequently, the NT plants remained severely affected by drought stress at the time at which some of the transgenic lines had partially recovered (Fig. 3B). To further verify this stress tolerance phenotype, we measured the Fv/Fm values of the transgenic and NT control plants, all at the vegetative stage (Fig. 3C). These values represent the maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII in a dark-adapted state (Fv, variable fluorescence; Fm, maximum fluorescence) and were found to be 15% to 30% higher in the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants compared with the NT plants under drought and low-temperature conditions. Under moderate salinity conditions, the Fv/Fm levels were also higher in both transgenic plants by 10% compared with the NT controls. In contrast, under severe salinity conditions, these levels were similar in all plant types. Our results thus indicate that the overexpression of OsNAC10 in transgenic rice primarily increases their tolerance to drought and low-temperature stress conditions during the vegetative stage of growth.

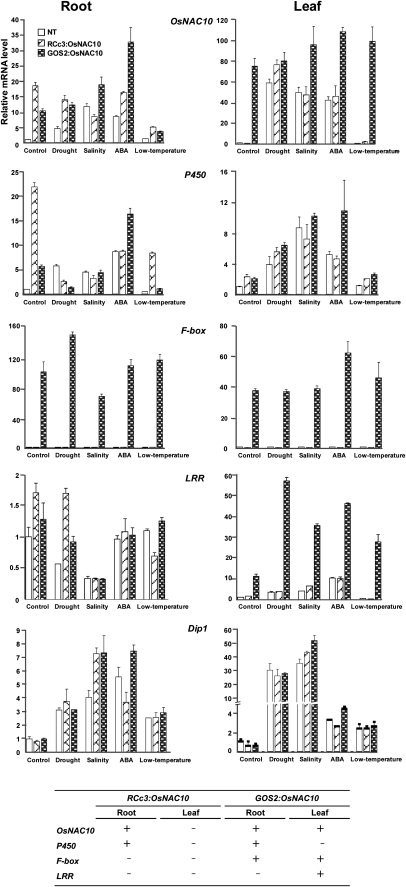

Identification of Genes Up-Regulated by Overexpressed OsNAC10

To identify genes that are up-regulated by the overexpression of OsNAC10, we performed expression profiling of the GOS2:OsNAC10 and RCc3:OsNAC10 plants in comparison with NT controls under normal growth conditions. This profiling was conducted using the Rice 3′-Tiling microarray with RNA samples extracted from 14-d-old roots and leaves of each plant, all grown under normal growth conditions. Each data set was obtained from three biological replicates. As listed in Table II and Supplemental Tables S1 and S2, statistical analysis of each data set using one-way ANOVA identified a total of 34 root-specific and 40 leaf-specific target genes that are up-regulated following OsNAC10 overexpression with a 3-fold or greater induction in the transgenic plants compared with NT plants (P < 0.05). More specifically, up-regulation of 34 genes was specific to roots of both RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, whereas up-regulation of 40 genes was specific to leaves of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. Surprisingly, only four genes were commonly activated in both roots and leaves of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, indicating that OsNAC10 activates different sets of target genes in different tissues. We selected 11 target genes (seven root specific, two leaf specific, and two common) and verified their OsNAC10-dependent expression patterns in roots and leaves of transgenic plants under normal growth conditions by real-time PCR (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S2). The OsNAC10 mRNA levels were higher in roots and leaves of GOS2:OsNAC10 plants but only in the roots of RCc3:OsNAC10 plants compared with the respective NT controls. Transcript levels of seven root-specific target genes [P450, Zn-finger, HAK5, 2OG-Fe(II), NCED, NAC, and KUP3] were increased in transgenic roots as compared with NT roots yet remained similar in leaves of all plant types, verifying their OsNAC10-dependent expression in roots. Conversely, expression of two leaf-specific target genes, LRR and Peroxidase, was found to be OsNAC10 dependent only in GOS2:OsNAC10 leaves but not in RCc3:OsNAC10 leaves. Expression of two common target genes, F-box and Muts4, was found to be OsNAC10 dependent both in roots and leaves of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. We also measured transcript levels of the 11 target genes in roots and leaves of RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT plants after exposure to drought, high salinity, and low-temperature conditions (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S2). Expression of the genes was further increased at various levels by stress treatments. Taken together, our results suggest that both the constitutive and root-specific overexpression of OsNAC10 enhances the stress tolerance of transgenic plants during the vegetative growth by activating different groups of target genes in different tissues.

Table II. Up-regulated genes in RCc3:OsNAC10 and/or GOS2:OsNAC10 plants in comparison with NT controls.

Numbers in boldface indicate up-regulation by more than 3-fold (P < 0.05). Boldface gene names indicate genes that were confirmed by quantitative PCR (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S2).

| Gene Name | Sequence IDa |

RCc3:OsNAC10 |

GOS2:OsNAC10 |

||||||

| Root |

Leaf |

Root |

Leaf |

||||||

| Meanb | Pc | Meanb | Pc | Meanb | Pc | Meanb | Pc | ||

| Genes up-regulated in roots of both RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants | |||||||||

| P450 | Os02g0503900 | 9.28 | 0.00 | 1.66 | 0.31 | 4.99 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.35 |

| KUP3 | Os09g0448200 | 7.76 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 5.73 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.68 |

| NCED | Os07g0154100 | 7.83 | 0.00 | 1.82 | 0.29 | 4.17 | 0.00 | 1.94 | 0.25 |

| Zn-finger | Os11g0702400 | 7.71 | 0.00 | 1.51 | 0.14 | 14.94 | 0.00 | −1.01 | 0.99 |

| HAK5 | Os03g0575200 | 6.17 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.76 | 3.04 | 0.00 | −1.45 | 0.70 |

| 2OG-Fe(II) | Os04g0581100 | 7.67 | 0.00 | 1.54 | 0.25 | 3.19 | 0.00 | 2.32 | 0.05 |

| NAC | Os11g0154500 | 3.89 | 0.00 | 2.43 | 0.19 | 6.64 | 0.00 | 1.58 | 0.47 |

| WRKY family transcription factor | Os09g0417800 | 7.56 | 0.00 | −1.32 | 0.77 | 5.94 | 0.00 | −4.12 | 0.17 |

| AP2 | Os08g0474000 | 5.79 | 0.00 | −1.84 | 0.19 | 4.11 | 0.00 | −1.55 | 0.33 |

| Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase | Os04g0339800 | 5.76 | 0.00 | 2.15 | 0.08 | 9.10 | 0.00 | 2.58 | 0.04 |

| HLH, helix-loop-helix domain | Os04g0301500 | 3.76 | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 3.67 | 0.00 | −1.44 | 0.39 |

| Cytochrome P450 family protein | Os02g0570700 | 3.46 | 0.00 | 2.15 | 0.25 | 7.89 | 0.00 | −1.11 | 0.86 |

| DUF581 | Os03g0183500 | 3.75 | 0.00 | 1.86 | 0.17 | 3.01 | 0.00 | 1.77 | 0.20 |

| Auxin-responsive SAUR gene family member | Os06g0671600 | 3.33 | 0.00 | −1.80 | 0.30 | 5.83 | 0.00 | −1.42 | 0.53 |

| 1-Deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase | Os07g0190000 | 3.16 | 0.00 | 1.48 | 0.61 | 5.32 | 0.00 | 1.59 | 0.55 |

| Late embryogenesis abundant protein | Os01g0705200 | 3.00 | 0.00 | −5.54 | 0.00 | 6.03 | 0.00 | −9.05 | 0.00 |

| Leu-rich repeat family protein | Os08g0203400 | 8.01 | 0.00 | −1.02 | 0.98 | 3.56 | 0.00 | 1.09 | 0.89 |

| WRKY family transcription factor | Os09g0417600 | 7.84 | 0.00 | −1.46 | 0.51 | 9.28 | 0.00 | −1.85 | 0.30 |

| Zinc finger family protein | Os11g0687100 | 5.14 | 0.00 | −1.14 | 0.69 | 8.97 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 0.44 |

| Lectin protein kinase | Os07g0130400 | 6.52 | 0.00 | −1.24 | 0.75 | 7.01 | 0.00 | −2.94 | 0.15 |

| Transmembrane protein kinase | Os07g0251900 | 3.97 | 0.00 | −1.81 | 0.07 | 4.68 | 0.00 | −3.89 | 0.00 |

| Wall-associated kinase | Os02g0111600 | 3.50 | 0.00 | −1.05 | 0.94 | 5.96 | 0.00 | 2.01 | 0.27 |

| Tyr kinase | Os10g0174800 | 3.49 | 0.00 | −4.98 | 0.05 | 6.67 | 0.00 | −3.77 | 0.09 |

| Acyl-CoA synthetase | Os03g0130100 | 3.87 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 0.59 | 3.42 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| Multicopper oxidases | Os09g0507300 | 3.16 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 4.22 | 0.00 | 1.15 | 0.71 |

| GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase | Os05g0376600 | 3.12 | 0.00 | −1.93 | 0.23 | 3.05 | 0.00 | −2.05 | 0.20 |

| Heavy metal transporter | Os04g0469000 | 3.86 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.70 | 3.53 | 0.00 | 1.34 | 0.31 |

| Detoxification protein | Os04g0464100 | 3.33 | 0.00 | 1.31 | 0.57 | 3.19 | 0.00 | −1.01 | 0.98 |

| Chitinase | Os01g0687400 | 3.08 | 0.00 | 1.11 | 0.75 | 3.49 | 0.00 | 2.60 | 0.03 |

| Glycosyl hydrolase | Os05g0298700 | 3.08 | 0.00 | −4.72 | 0.00 | 3.52 | 0.00 | −3.84 | 0.00 |

| Protein kinase | Os10g0134500 | 4.49 | 0.00 | 1.79 | 0.09 | 6.02 | 0.00 | 1.56 | 0.18 |

| Protein kinase domain-containing protein | Os10g0151100 | 3.19 | 0.00 | −3.62 | 0.01 | 4.48 | 0.00 | −3.89 | 0.01 |

| Protein kinase domain-containing protein | Os11g0694100 | 3.13 | 0.00 | 1.89 | 0.10 | 3.64 | 0.00 | 2.17 | 0.06 |

| SAM-dependent methyltransferases | Os04g0104900 | 3.09 | 0.00 | 1.88 | 0.32 | 5.43 | 0.00 | −1.06 | 0.92 |

| Genes up-regulated in both roots and leaves of GOS2:OsNAC10 plants | |||||||||

| F-box | Os11g0539600 | 1.35 | 0.15 | −1.12 | 0.82 | 7.36 | 0.00 | 8.58 | 0.00 |

| MutS | Os07g0486000 | −1.81 | 0.07 | 1.30 | 0.73 | 53.93 | 0.00 | 10.02 | 0.02 |

| Casein kinase | Os03g0762000 | −1.12 | 0.40 | 1.27 | 0.59 | 6.29 | 0.00 | 14.93 | 0.00 |

| Epoxide hydrolase | Os10g0498300 | −1.04 | 0.88 | 1.30 | 0.54 | 42.54 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 0.02 |

Sequence identification numbers for the full-length cDNA sequences of the corresponding genes.

The mean of three independent biological replicates. These microarray data sets can be found at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ (Gene Expression Omnibus).

P values were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

Figure 4.

Regulated genes in roots and leaves of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants under normal and stress conditions. The transcript levels of OsNAC10 and six target genes were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (using the primers listed in Supplemental Table S5), and those in RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 transgenic rice plants are presented as relative to the levels in untreated NT control roots and leaves, respectively. Data were normalized using the rice ubiquitin gene (OsUbi) transcript levels. Values are means ± sd of three independent experiments.

Root-Specific Overexpression of OsNAC10 Increases Rice Grain Yield under Field Drought Conditions

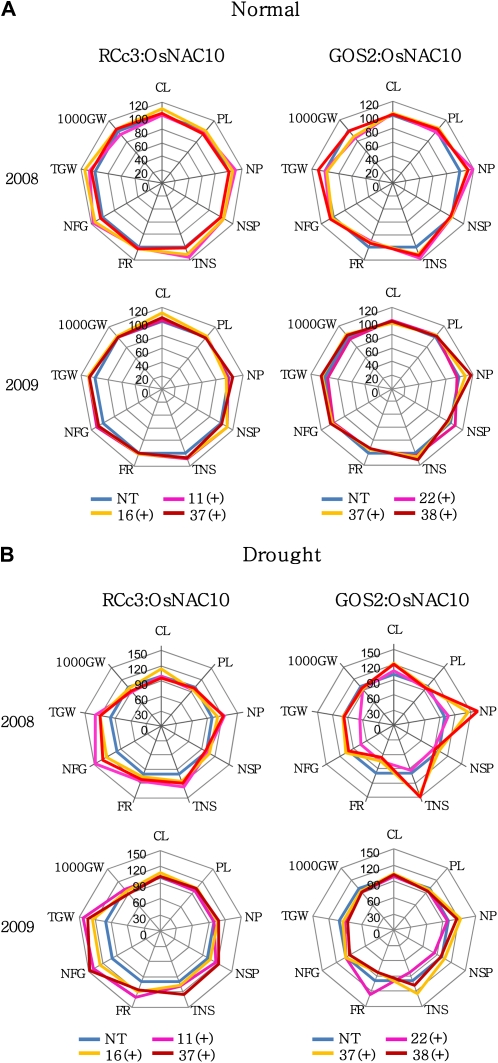

A phenotypic evaluation of RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT control plants revealed no major differences at the vegetative growth stage of the entire plants. We evaluated yield components of the transgenic plants under normal and field drought conditions for two cultivating seasons (2008 and 2009). Three independent T4 (2008) and T5 (2009) homozygous lines of each of the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, together with NT controls, were transplanted to a paddy field and grown to maturity. Yield parameters were scored for 20 (2008) and 30 (2009) plants per transgenic line from two (2008) and three (2009) replicates. Two data sets are generally consistent, with the 2009 data exhibiting greater statistical rigor. The grain yield of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants remained similar to that of the NT controls under normal field conditions in both seasons (Fig. 5A; Supplemental Table S3). Filling rate and 1,000 grain weight of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants were markedly reduced, and the reduction appeared to be balanced by the increase in numbers of panicles and total spikelets, consequently maintaining similar levels of total grain weight to that of the NT controls. In the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants under the same field conditions, however, total grain weight was increased by 5% to 14% compared with the NT controls, which was due to increased numbers of filled grains and total spikelets. These observations prompted us to examine the yield components of the transgenic rice plants grown under field drought conditions. Three independent T4 (2008) and T5 (2009) lines of the RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT plants were transplanted to a paddy field with a removable rain-off shelter and exposed to drought stress at the panicle heading stage (from 10 d before heading to 20 d after heading). The level of drought stress imposed under the rain-off shelter was equivalent to those that give 40% to 50% of total grain weight obtained under normal growth conditions, which was evidenced by the difference in levels of total grain weight of NT plants between the normal and drought conditions (Supplemental Tables S3 and S4). Statistical analysis of the yield parameters scored for two cultivating seasons showed that the decrease in grain yield under drought conditions was significantly smaller in the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants than that observed in the NT controls. Specifically, in the drought-treated RCc3:OsNAC10 plants, the number of filled grains was 26% to 47% higher than the drought-treated NT plants, which resulted in a 25% to 42% increase in the total grain weight, depending on transgenic line (Fig. 5; Supplemental Table S4). In the drought-treated GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, in contrast, the total grain weight remained similar to the drought-treated NT controls. Given the similar levels of drought tolerance during the vegetative stage in the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, these differences in grain yield under field drought conditions are surprising. Unlike in RCc3:OsNAC10 plants, spikelet development in GOS2:OsNAC10 plants is significantly affected by the constitutive overexpression of OsNAC10 under both normal and drought conditions.

Figure 5.

Agronomic traits of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants grown in the field under both normal and drought conditions. Spider plots of the agronomic traits of three independent homozygous T4 and T5 lines of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants and corresponding NT controls under both normal and drought conditions were drawn using Microsoft Excel. Each data point represents the percentage of the mean values (n = 20 and n = 30) listed in Supplemental Tables S3 and S4. The mean measurements from the NT controls were assigned a 100% reference value. CL, Culm length; PL, panicle length; NP, number of panicles per hill; NSP, number of spikelets per panicle; TNS, total number of spikelets; FR, filling rate; NFG, number of filled grains; TGW, total grain weight; 1,000GW, 1,000 grain weight.

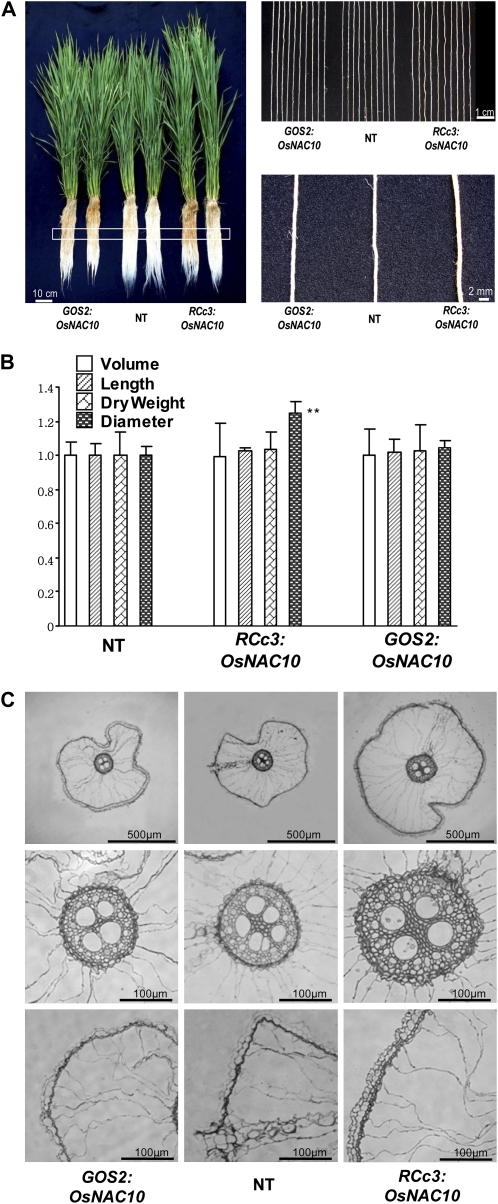

We have measured root volume, length, dry weight, and diameter of RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT plants after growth to the heading stage of reproduction (Fig. 6). As shown in Figure 6, root diameter of the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants was thicker by 1.25-fold than that of the GOS2:OsNAC10 and NT plants. Microscopic analysis of cross-sectioned roots revealed that the increase in root diameter was due to the enlarged stele, cortex, and epidermis of RCc3:OsNAC10 roots. These observations suggest that root-specific overexpression of OsNAC10 enlarges roots, enhancing drought tolerance of transgenic plants at the reproductive stage.

Figure 6.

Difference in root growth of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. A, RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT control plants were grown to the heading stage of reproduction. Whole plants (left panel) and parts (white box in left panel) of representative roots (10 roots in top right panel and one root in bottom right panel) are shown. Bars = 10 cm in left panel and 1 cm and 2 mm in right panels. B, The root volume, length, dry weight, and diameter of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants are normalized to those of NT control roots. Asterisks indicate that the mean difference is significant at the 0.01 level (lsd). Values are means ± sd of 50 roots (10 roots from each of five plants). C, Light microscopic images of cross-sectioned RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT roots (top panels) showing the enlarged stele (middle panels), cortex, and epidermis (bottom panels) of RCc3:OsNAC10 roots. Bars = 500 μm in top panels and 100 μm in middle and bottom panels.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we performed expression profiling using RNAs from stress-treated rice plants and identified 18 NAC domain factors that are stress inducible (Table I). Alignment of these stress-inducible factors further revealed three subgroups, within which the members are more closely related, suggesting a common stress response function. Overexpression of one such gene, OsNAC10, under the control of the constitutive promoter GOS2 (GOS2:OsNAC10) and the root-specific promoter RCc3 (RCc3:OsNAC10) was found to increase rice plant tolerance to drought and low temperature at the vegetative stage of growth. Increased tolerance to a moderate level of salinity conditions was also observed in both of these transgenic plants. More importantly, the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants showed significantly enhanced drought tolerance at the reproductive stage, increasing grain yield by 25% to 42% and by 5% to 14% over controls in the field under drought and normal conditions, respectively. These results were consistent in our evaluations for two consecutive years (2008 and 2009). In contrast, grain yield in GOS2:OsNAC10 plants in the field remained similar to that of controls under both normal and drought conditions. In GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, the increased expression of OsNAC10 in the whole plant body, including floral organs, resulted in a large reduction in filling rate under both normal and drought conditions. In particular, the large decrease in filling rate of GOS2:OsNAC10 plants under drought conditions did not allow the total grain weight to increase, even with the significant increase in numbers of panicles, and spikelets per panicle, over the controls. The RCc3:OsNAC10 plants, in contrast, were effective against drought stress at both the reproductive and vegetative stages. The root-specific overexpression of OsNAC10 does not seem to affect the development of reproductive organs while conferring stress tolerance in the transgenic plants. The lower decrease in the filling rate as well as in the numbers of panicles and spikelets per panicle in RCc3:OsNAC10 plants than in NT controls under drought conditions is clear evidence of drought tolerance at the reproductive stage.

The vegetative growth of both the GOS2:OsNAC10 and RCc3:OsNAC10 plants was visually indistinguishable from the NT controls. Given the different numbers of target genes that are up-regulated in RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 roots and leaves, differences in their response to drought at the reproductive stage were not unexpected. Our microarray experiments identified 44 and 59 up-regulated root-expressed genes that are specific to the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, respectively, in addition to the 34 up-regulated root-expressed genes that are common to both plants. We also learned that OsNAC10-dependent target genes identified in roots are very different from those in leaves of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. Only four out of 40 target genes are common to both leaves and roots of the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. Our real-time PCR experiments verified their OsNAC10-dependent up-regulation in roots and/or leaves of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants. In addition, expression patterns and levels of the target genes were very different in roots and leaves of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants under both unstressed and stressed conditions (Fig. 4; Supplemental Fig. S2). These observations led us to conclude that OsNAC10 regulates different sets of target genes in different tissues at various stages of plant growth. And the difference in drought tolerance between RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants at the reproductive stage reflects the difference in expression of target genes in leaves as well as in roots. One is often aware of discrepancies in lists of target genes identified in transgenic rice with the same transgene. For example, none of the target genes identified in transgenic rice with Ubi:OsNAC6 (or SNAC2; Nakashima et al., 2007) is overlapped with those identified in transgenic rice with Ubi:SNAC2 (or OsNAC6; Hu et al., 2008). The microarray experiments were performed using 14-d-old seedlings for the former and four-leaf stage leaf tissues for the latter. Similarly, two research groups (Oh et al., 2005; Ito et al., 2006) have reported very different lists of target genes identified in transgenic rice plants with the same transgene, Ubi:CBF3/DREB1A. Thus, it is not surprising to see the differences if the target genes analyzed were in different tissues and/or stages of transgenic plants. We do not rule out the possibility that such discrepancies may have been in part due to the different genetic backgrounds of rice cultivars.

The target genes identified in both the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 roots include genes that function in stress responses, such as Cytochrome P450, NCED, and Potassium transporter HAK5. Also included are seven protein kinases and five transcription factors containing domains such as AP2, WRKY, LRR, NAC, and Zn-finger that also function in stress tolerance pathways. We further identified target genes encoding proteins that function as osmolytes, such as Potassium transporter KUP3 and Heavy metal transporter, and that function in reactive oxygen species-scavenging systems, such as Multicopper oxidase, Detoxification protein, Chitinase, and Glycosyl hydrolase. The expression of such target genes may enhance grain yield under both normal and drought conditions.

Recently, the SNAC1 gene, a member of our subgroup I (Table I), was shown to confer tolerance of transgenic rice plants to field drought conditions as well as to drought and high salinity at the vegetative stage (Hu et al., 2006). This is consistent with our results here for RCc3:OsNAC10 plants. In the case of low temperatures at the vegetative stage, however, the effect was more pronounced in our transgenic plants harboring OsNAC10. In addition, SNAC1did not affect grain yield in transgenic plants grown under normal conditions, while a 5% to 14% increase in grain yield was observed in our RCc3:OsNAC10 plants in normal field conditions. Transgenic rice harboring OsNAC6 (or SNAC2), another member of subgroup I, was shown previously to display enhanced tolerance at the vegetative stage to cold, salt, and blast disease as a result of the increased expression of stress-related genes (Nakashima et al., 2007; Hu et al., 2008). Despite their high protein sequence homology (70%–73%) within the NAC domain, the SNAC1 and OsNAC6 (or SNAC2) genes are distinct from OsNAC10 in that their expression is increased upon exposure to low-temperature conditions (Table I), which may be responsible in part for the observed functional differences between these genes and OsNAC10.

To date, the potential impact of homeotic genes like the NAC factors upon grain yield have received relatively little attention due to their negative effects on fertility, plant growth, and development. Transgenic rice plants overexpressing OsNAC6 in a whole plant body exhibit growth retardation and low reproductive yield (Nakashima et al., 2007). In this study, we also observed a yield penalty under drought conditions when the OsNAC10 overexpressed in a whole body in the GOS2:OsNAC10 plants; in RCc3:OsNAC10 plants, however, significant increase in grain yield was observed. Interestingly, the targeted expression of the prokaryotic Na+/H+ antiporter gene in roots of transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants has been shown to confer a higher tolerance to high-salinity conditions compared with whole plant expression (Hossain et al., 2006). More importantly, Na+ content in leaves of transgenic tobacco plants with root-specific expression of the Na+/H+ antiporter was lower than that of plants that constitutively expressed this gene, although there was no expression of this transgene in the leaf of the former. These observations together with our results suggest that ectopic expression of a stress response gene in a whole plant may not be as effective as root-specific expression on stress tolerance. This is particularly true for homeotic genes that function in the development of reproductive organs.

The Arabidopsis HARDY (HRD) gene, an AP2 transcription factor, has been previously found to provide enhanced drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis and rice plants (Karaba et al., 2007). HRD was isolated by activation tagging in Arabidopsis; the activation-tagged line had a robust root system with increased numbers of secondary and tertiary roots. We have measured root volume, length, dry weight, and diameter of RCc3:OsNAC10, GOS2:OsNAC10, and NT plants after growth to the stage of reproduction (Fig. 6). Root diameter of the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants was thicker than that of the GOS2:OsNAC10 and NT plants. The increase in root diameter of the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants appears to be caused by an increase in cell number rather than cell size, as evidenced by the similar size of epidermal and exodermal cells between NT and RCc3:OsNAC10 roots. It was shown that vigorous growth of roots with an increase in length and thickness is correlated with drought tolerance and grain yield of rice (Ekanayake et al., 1985; Price et al., 1997). How the thicker roots of the RCc3:OsNAC10 plants are associated with higher grain yield remains to be investigated.

In summary, we report an analysis of the rice NAC domain family in their responses to stress treatments. More importantly, we evaluated agronomic traits in transgenic crops throughout the entire stages of plant growth in the field, which allowed us to address the advantages of using such a regulatory gene as OsNAC10 for improving stress tolerance. Finally, we demonstrated that a root-specific rather than whole body expression of OsNAC10 increases rice grain yield under drought conditions without yield penalty, providing the potential use of this strategy for improving drought tolerance in other crops.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction and Transformation of Rice

The coding region of OsNAC10 was amplified from rice (Oryza sativa) total RNA using an RT-PCR system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer pairs were as follows: forward (5′-ATGCCGAGCAGCGGCGGCGC-3′) and reverse (5′-CTACTGCATCTGCAGATGAT-3′). To enable the overexpression of the OsNAC10 gene in rice, the cDNA for this gene was linked to the GOS2 promoter for constitutive expression and to the RCc3 promoter for root-specific expression using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). Plasmids were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 by triparental mating, and embryogenic (cv Nipponbare) calli from mature seeds were transformed as described previously (Jang et al., 1999).

Protein Sequence Analysis

Of 140 NAC factors predicted from the rice genome (Fang et al., 2008), we selected 87 NAC protein sequences that have full-length EST information from a National Center for Biotechnology Information database search using the tBLASTN program and previously reported annotation of the NAC family (Ooka et al., 2003; Xiong et al., 2005). Amino acid sequences of 87 NAC domains were aligned using ClustalW followed by construction of a neighbor-joining phylogenic tree using the MEGA program (B = 1,000 bootstrap replications).

Northern-Blot Analysis

Rice (cv Nipponbare) seeds were germinated in soil and grown in a glasshouse (16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle) at 22°C. For high-salinity and ABA treatments, 14-d-old seedlings were transferred to nutrient solution containing 400 mm NaCl or 100 μm ABA for the indicated periods in the glasshouse under continuous light of approximately 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1. For drought treatment, 14-d-old seedlings were excised and air dried for the indicated time course under continuous light of approximately 1,000 μmol m−2 s−1. For low-temperature treatments, 14-d-old seedlings were exposed at 4°C in a cold chamber for the indicated time course under continuous light of 150 μmol m−2 s−1. The preparation of total RNA and RNA gel-blot analysis were performed as reported previously (Jang et al., 2002).

Drought Treatments of Rice Plants at the Vegetative Stage

Transgenic and NT rice (cv Nipponbare) seeds were germinated in half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) solid medium in a growth chamber in the dark at 28°C for 4 d, transplanted into soil, and then grown in a greenhouse (16-h-light/8-h-dark cycles) at 28°C to 30°C. Eighteen seedlings from each transgenic and NT line were grown in pots (3 × 3 × 5 cm; one plant per pot) for 4 weeks before undertaking the drought stress experiments. To induce drought stress, 4-week-old transgenic and NT seedlings were unwatered for 3 d followed by 7 d of watering. The numbers of plants that survived or continued to grow were then scored.

Measurement of Chlorophyll Fluorescence under Drought, High-Salinity, and Low-Temperature Conditions

Transgenic and NT rice (cv Nipponbare) seeds were germinated and grown in half-strength MS solid medium for 14 d in a growth chamber (16-h-light [150 μmol m−2 s–1]/8-h-dark cycle at 28°C). The green portions of approximately 10 seedlings were then cut using a scissors prior to stress treatments in vitro. All stress treatments were conducted under continuous light at 150 μmol m−2 s –1. To induce low-temperature stress, the seedlings were incubated at 4°C in water for up to 6 h. High-salinity stress was induced by incubation in 400 mm NaCl for 2 h at 28°C. To simulate drought stress, the plants were air dried for 2 h at 28°C. Fv/Fm values were then measured as described previously (Oh et al., 2008).

Rice 3′-Tiling Microarray Analysis

Expression profiling was conducted using the Rice 3′-Tiling microarray as described previously (Oh et al., 2009). Transgenic and NT rice (cv Nipponbare) seeds were germinated in soil and grown in a glasshouse (16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle) at 22°C. To identify stress-inducible NAC genes in rice, total RNA (100 μg) was prepared from 14-d-old leaves of plants subjected to drought, high-salinity, ABA, and low-temperature stress conditions. For high-salinity and ABA treatments, the 14-d-old seedlings were transferred to a nutrient solution containing 400 mm NaCl or 100 μm ABA for 2 h in the greenhouse under continuous light of approximately 1,000 μmol m−2 s −1. For drought treatment, 14-d-old seedlings were air dried for 2 h also under continuous light of approximately 1,000 μmol m−2 s −1. For low-temperature treatment, 14-d-old seedlings were exposed at 4°C in a cold chamber for 6 h under continuous light of 150 μmol m−2 s−1. For identification of genes up-regulated in RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, total RNA (100 μg) was prepared from root and leaf tissues of 14-d-old transgenic and NT rice seedlings (cv Nipponbare) grown under normal growth conditions.

Quantitative PCR Analysis

Total RNA was prepared as reported previously (Kim et al., 2009). For quantitative real-time PCR experiments, a SuperScript III Platinum One-Step Quantitative RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) was used. For PCR, a master mix of reaction components was prepared as reported previously (Oh et al., 2009) using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen). Thermocycling and fluorescence detection were performed using a Stratagene Mx3000p Real-Time PCR machine (Stratagene). PCR was performed at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min. To validate our quantitative PCR results, we repeated each experiment three times. The primer pairs are listed in Supplemental Table S5.

Drought Treatments and Grain Yield Analysis of Rice Plants in the Field for Two Years (2008 and 2009)

To evaluate yield components of transgenic plants under normal field conditions, three independent T4 (2008) and T5 (2009) homozygous lines of the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants, together with NT controls, were transplanted to a paddy field at the Rural Development Administration, Suwon, Korea. A randomized design was employed with two (2008) and three (2009) replicates. At 25 d after sowing, the seedlings were randomly transplanted with 15- × 30-cm spacing and a single seedling per hill. Fertilizer was applied at 70:40:70 (nitrogen:phosphorus:potassium) kg ha−1 after the last paddling and 45 d after transplantation. Yield parameters were scored for 20 (2008) and 30 (2009) plants per transgenic line. Plants located at borders were excluded from data scoring.

To evaluate yield components of transgenic plants under drought field conditions, three independent T4 (2008) and T5 (2009) homozygous lines of each of the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants and NT controls were transplanted to a removable rain-off shelter (located at Myongji University, Yongin, Korea) with a 1-m-deep container filled with natural paddy soil.

The experimental design, transplanting spacing, use of fertilizer, drought treatments, and scoring of agronomic traits were as described (Oh et al., 2009). When the plants grown under normal and drought conditions had reached maturity and the grains had ripened, they were harvested and threshed by hand (separation of seeds from the vegetative parts of the plant). The unfilled and filled grains were then taken apart, independently counted using a Countmate MC1000H (Prince Ltd.), and weighed. The following agronomic traits were scored: flowering date, panicle length, number of tillers, number of panicles, spikelets per panicle, filling rate (%), total grain weight (g), and 1,000 grain weight (g). The results from three independent lines were separately analyzed by one-way ANOVA and compared with those of the NT controls. The ANOVA was used to reject the null hypothesis of equal means of transgenic lines and NT controls (P < 0.05). SPSS version 16.0 was used to perform these statistical analyses.

Microscopic Examination of Roots

Roots of transgenic and NT plants at the panicle heading stage were fixed with modified Karnovsky's fixative, consisting of 2% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 2% (v/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.05 m sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2), at 4°C overnight and washed with the same buffer three times for 10 min each. They were postfixed with 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide in the same buffer at 4°C for 2 h and washed with distilled water two times briefly. The postfixed root tissues were enbloc stained with 0.5% (w/v) uranyl acetate at 4°C overnight. They were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 95%, and 100%) and three times in 100% ethanol for 10 min each. Dehydrated samples were further treated with propylene oxide as a transitional fluid two times for 30 min each and embedded in Spurr's medium. Ultrathin sections (approximately 1 μm thick) were made with a diamond knife by an ultramicrotome (MT-X; RMC). The sections were stained with 1% toluidine blue and observed and photographed with a light microscope.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Phylogenic relationship of the rice NAC family.

Supplemental Figure S2. Regulated genes in roots and leaves of RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 plants under normal and stress conditions.

Supplemental Table S1. Up-regulated root-expressed genes in either RCc3:OsNAC10 or GOS2:OsNAC10 plants in comparison with NT controls.

Supplemental Table S2. Up-regulated leaf-expressed genes in GOS2:OsNAC10 plants in comparison with NT controls.

Supplemental Table S3. Agronomic traits of the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 transgenic rice plants under normal field conditions.

Supplemental Table S4. Agronomic traits of the RCc3:OsNAC10 and GOS2:OsNAC10 transgenic rice plants under field drought conditions.

Supplemental Table S5. Primer list for PCR.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aida M, Ishida T, Fukaki H, Fujisawa H, Tasaka M. (1997) Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: an analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. Plant Cell 9: 841–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EA. (1993) Molecular responses to water deficit. Plant Physiol 103: 1035–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson JA, Wilson IW, Llewellyn DJ, Dennis ES. (2009) The low-oxygen induced NAC domain transcription factor ANAC102 affects viability of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds following low-oxygen treatment. Plant Physiol 149: 1724–1738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinge M, Boller T. (2001) Differential induction of two potato genes, Stprx2 and StNAC, in response to infection by Phytophthora infestans and to wounding. Plant Mol Biol 46: 521–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pater BS, van der Mark F, Rueb S, Katagiri F, Chua NH, Schilperoort RA, Hensgens LA. (1992) The promoter of the rice gene GOS2 is active in various different monocot tissues and bind rice nuclear factor ASF-1. Plant J 2: 837–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake IJ, O'Toole JC, Garrity DP, Masajo TM. (1985) Inheritance of root characters and their relations to drought resistance in rice. Crop Sci 25: 927–933 [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, You J, Xie K, Xie W, Xiong L. (2008) Systematic sequence analysis and identification of tissue-specific or stress-responsive genes of NAC transcription factor family in rice. Mol Genet Genomics 280: 547–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M, Fujita Y, Maruyama K, Seki M, Hiratsu K, Ohme-Takagi M, Tran LS, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. (2004) A dehydration-induced NAC protein, RD26, is involved in a novel ABA-dependent stress-signaling pathway. Plant J 39: 863–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg AK, Kim JK, Owens TG, Ranwala AP, Choi YD, Kochian LV, Wu RJ. (2002) Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 15898–15903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XJ, Mu RL, Cao WH, Zhang ZG, Zhang JS, Chen SY. (2005) AtNAC2, a transcription factor downstream of ethylene and auxin signaling pathways, is involved in salt stress response and lateral root development. Plant J 44: 903–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus D, Yu M, Baldwin D, Gruber M, Sharpe A, Parkin I, Whitwill S, Lydiate D. (2003) Molecular characterization of Brassica napus NAC domain transcriptional activators induced in response to biotic and abiotic stress. Plant Mol Biol 53: 383–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiei Y, Ohta S, Komari T, Kumashiro T. (1994) Efficient transformation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) mediated by Agrobacterium and sequence analysis of the boundaries of the T-DNA. Plant J 6: 271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain GS, Waditee R, Hibino T, Tanaka Y, Takabe T. (2006) Root specific expression of Na+/H+ antiporter gene from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 confers salt tolerance of tobacco plant. Plant Biotechnol 23: 275–281 [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Dai M, Yao J, Xiao B, Li X, Zhang Q, Xiong L. (2006) Overexpressing a NAM, ATAF, and CUC (NAC) transcription factor enhances drought resistance and salt tolerance in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 35: 12987–12992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, You J, Fang Y, Zhu X, Qi Z, Xiong L. (2008) Characterization of transcription factor gene SNAC2 conferring cold and salt tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol 67: 169–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Katsura K, Maruyama K, Taji T, Kobayashi M, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2006) Functional analysis of rice DREB1/CBF-type transcription factors involved in cold-responsive gene expression in transgenic rice. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Choi WB, Lee KH, Song SI, Nahm BH, Kim JK. (2002) High-level and ubiquitous expression of the rice cytochrome c gene OsCc1 and its promoter activity in transgenic plants provides a useful promoter for transgenesis of monocots. Plant Physiol 129: 1473–1481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Nahm BH, Kim JK. (1999) Subcellular targeting of green fluorescent protein to plastids in transgenic rice plants provides a high-level expression system. Mol Breed 5: 453–461 [Google Scholar]

- Jang IC, Oh SJ, Seo JS, Choi WB, Song SI, Kim CH, Kim YS, Seo HS, Choi YD, Nahm BH, et al. (2003) Expression of a bifunctional fusion of the Escherichia coli genes for trehalose-6-phosphate synthase and trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase in transgenic rice plants increases trehalose accumulation and abiotic stress-tolerance without stunting growth. Plant Physiol 131: 516–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong JS, Park YT, Jung H, Park SH, Kim JK. (2009) Rice NAC proteins act as homodimers and heterodimers. Plant Biotechnol Rep 3: 127–134 [Google Scholar]

- Karaba A, Dixit S, Greco R, Aharoni A, Trijatmiko KR, Marsch-Martinez N, Krishnan A, Nataraja KN, Udayakumar M, Pereira A. (2007) Improvement of water use efficiency in rice by expression of HARDY, an Arabidopsis drought and salt tolerance gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15270–15275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga M, Liu Q, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. (1999) Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nat Biotechnol 17: 287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi S, Satoh K, Nagata T, Kawagashira N, Doi K, Kishimoto N, Yazaki J, Ishikawa M, Yamada H, Ooka H, et al. (2003) Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science 301: 376–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim EH, Kim YS, Park SH, Koo YJ, Choi YD, Chung YY, Lee IJ, Kim JK. (2009) Methyl jasmonate reduces grain yield by mediating stress signals to alter spikelet development in rice. Plant Physiol 149: 1751–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, Abe H, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. (1998) Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 10: 1391–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Tran LS, Van Nguyen D, Fujita M, Maruyama K, Todaka D, Ito Y, Hayashi N, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2007) Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant J 51: 617–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Kim SJ, Kim YS, Park SH, Ha SH, Kim JK. (2008) Arabidopsis cyclin D2 expressed in rice forms a functional cyclin-dependent kinase complex that enhances seedling growth. Plant Biotechnol Rep 2: 227–231 [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Kim YS, Kwon CW, Park HK, Jeong JS, Kim JK. (2009) Overexpression of transcription factor AP37 in rice improves grain yield under drought conditions. Plant Physiol 150: 1368–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Kwon CW, Choi DW, Song SI, Kim JK. (2007) Expression of barley HvCBF4 enhances tolerance to abiotic stress in transgenic rice. Plant Biotechnol J 5: 646–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Song SI, Kim YS, Jang HJ, Kim SY, Kim M, Kim YK, Nahm BH, Kim JK. (2005) Arabidopsis CBF3/DREB1A and ABF3 in transgenic rice increased tolerance to abiotic stress without stunting growth. Plant Physiol 138: 341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooka H, Satoh K, Doi K, Nagata T, Otomo Y, Murakami K, Matsubara K, Osato N, Kawai J, Carninci P, et al. (2003) Comprehensive analysis of NAC family genes in Oryza sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Res 20: 239–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AH, Tomos AD, Virk DS. (1997) Genetic dissection of root growth in rice (Oryza sativa L.). I. A hydrophonic screen. Theor Appl Genet 95: 132–142 [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann JL, Heard J, Martin G, Reuber L, Jiang C, Keddie J, Adam L, Pineda O, Ratcliffe OJ, Samaha RR, et al. (2000) Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290: 2105–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sablowski RW, Meyerowitz EM. (1998) A homolog of NO APICAL MERISTEM is an immediate target of the floral homeotic genes APETALA3/PISTILLATA. Cell 92: 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Seki M. (2003) Regulatory network of gene expression in the drought and cold stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 410–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souer E, van Houwelingen A, Kloos D, Mol J, Koes R. (1996) The no apical meristem gene of petunia is required for pattern formation in embryos and flowers and is expressed at meristem and primordia boundaries. Cell 85: 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow MF. (1999) Plant cold acclimation: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50: 571–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran LS, Nakashima K, Sakuma Y, Simpson SD, Fujita Y, Maruyama K, Fujita M, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2004) Isolation and functional analysis of Arabidopsis stress-inducible NAC transcription factors that bind to a drought-responsive cis-element in the early responsive to dehydration stress 1 promoter. Plant Cell 16: 2481–2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uaury C, Distelfeld A, Fahima T, Blechl A, Dubcovsky J. (2006) A NAC gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat. Science 314: 1298–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Huang Y, Tang N, Xiong L. (2007) Over-expression of a LEA gene in rice improves drought resistance under the field conditions. Theor Appl Genet 115: 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Frugis G, Colgan D, Chua NH. (2000) Arabidopsis NAC1 transduces auxin signal downstream of TIR1 to promote lateral root development. Genes Dev 14: 3024–3036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y, Liu T, Tian C, Sun S, Li J, Chen M. (2005) Transcription factors in rice: a genome-wide comparative analysis between monocots and eudicots. Plant Mol Biol 59: 191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Duan X, Wang B, Hong B, Ho T, Wu R. (1996) Expression of a late embryogenesis abundant protein gene, HVA1, from barley confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol 110: 249–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Buchholz WG, DeRose RT, Hall TC. (1995) Characterization of a rice gene family encoding root-specific proteins. Plant Mol Biol 27: 237–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.