Abstract

Ectocarpus siliculosus is a small brown alga that has recently been developed as a genetic model. Its thallus is filamentous, initially organized as a main primary filament composed of elongated cells and round cells, from which branches differentiate. Modeling of its early development suggests the involvement of very local positional information mediated by cell-cell recognition. However, this model also indicates that an additional mechanism is required to ensure proper organization of the branching pattern. In this paper, we show that auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is detectable in mature E. siliculosus organisms and that it is present mainly at the apices of the filaments in the early stages of development. An in silico survey of auxin biosynthesis, conjugation, response, and transport genes showed that mainly IAA biosynthesis genes from land plants have homologs in the E. siliculosus genome. In addition, application of exogenous auxins and 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid had different effects depending on the developmental stage of the organism, and we propose a model in which auxin is involved in the negative control of progression in the developmental program. Furthermore, we identified an auxin-inducible gene called EsGRP1 from a small-scale microarray experiment and showed that its expression in a series of morphogenetic mutants was positively correlated with both their elongated-to-round cell ratio and their progression in the developmental program. Altogether, these data suggest that IAA is used by the brown alga Ectocarpus to relay cell-cell positional information and induces a signaling pathway different from that known in land plants.

Brown algae are multicellular organisms that belong to the phylum Heterokontophyta, which also includes the oomycetes. The divergence between heterokonts and other phyla comprising multicellular organisms, such as Opisthokonta (metazoa and fungi), Viridiplantae, and the red algal lineage, is dated to more than 1,000 million years ago (Yoon et al., 2004). On the one hand, brown algae share several obvious features with land plants, such as the presence of a cell wall, although with a different composition (Kloareg and Quatrano, 1988), and similar growth metabolism and response (i.e. photosynthesis and phototropism). On the other hand, brown algae share subcellular features with animal cells, such as the presence of centrosomes (Katsaros et al., 2006), and some aspects of their metabolism (production of eicosanoid oxylipins; Ritter et al., 2008). Brown algae are coastal organisms, requiring strong attachment or adherence to rocks or other substrates (other algae, etc.) in order to survive. Their economic potential is important in some areas of the globe, with Asia considering them as a central part of their diet (wakame, kombu) and Europe using them as a source of fertilizers, cosmetics, pharmacological products, and defense elicitors (Klarzynski et al., 2000; Abad et al., 2008; Holtkamp et al., 2009).

Diverse morphologies are observed in brown algae, from crust-like forms to the large thallus blades found in giant kelps. Fucales have long been good models for investigating brown alga and land plant embryogenesis. Given its large size and its ease of manipulation, the Fucales zygote has been particularly amenable to cytological and pharmacological experiments (Kropf, 1997). Polarization of the zygote after fertilization involves several subcellular components (cell wall, microtubules, centrioles, and actin; for review, see Kropf, 1992) and is affected by auxin, which alters the polarity of the embryo and its developmental pattern (Basu et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2004). However, Fucus is not amenable to genetic studies, limiting its utility in further investigations of the processes controlling morphogenesis in brown algae.

Recently, Ectocarpus siliculosus (order Ectocarpales) was chosen as a genetic and genomic model of brown algae (Peters et al., 2004). It is a small macroscopic filamentous alga that grows in temperate regions throughout the globe, and knowledge on this organism has been compiled over the last two centuries (Charrier et al., 2008). Its relatively small (200 Mb) genome has been sequenced and annotated (http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/spip/Ectocarpus-siliculosus,740.html). Unlike Fucus, fertilization is isogamous in E. siliculosus, which entails little, if any, parental influence on the development of the zygote (Stern, 2006). For organisms with isogamous fertilization, the perception of physical factors such as gravity and light is determinant for organismal development (Cove, 2000). However, the perception of these factors is diminished in a marine environment, making the embryonic developmental mechanisms in E. siliculosus a particularly pertinent issue worthy of investigation.

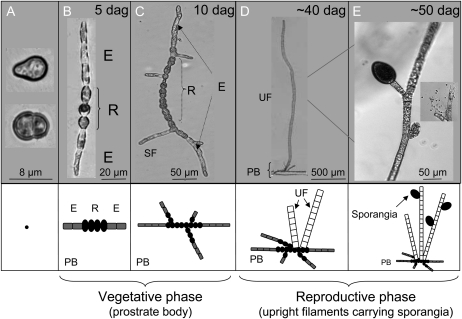

E. siliculosus develops uniseriate filaments, resulting in one of the simplest architectures of multicellular organisms. Its sporophyte body is composed of two mains parts: the prostrate body (Fig. 1, A–C) and the upright body (Fig. 1, D–E). The prostrate body is made of crawling filaments composed of two cell types. Elongated (E) cells are localized at the apices, where they ensure the apical growth by cell division and elongation. They then progressively differentiate centripetally to produce the second cell type, the round (R) cells, thereby generating filaments with E cells on the edges and R cells in the center (Fig. 1B; Le Bail et al., 2008a). Then, secondary growth axes develop, preferentially in the center of the primary filament and on the R cells (Fig. 1C; Le Bail et al., 2008a). Upright filaments then develop from the prostrate body and ultimately differentiate into sporangia (Fig. 1, D and E). This early developmental pattern is subject to a significant level of stochasticity in terms of the proportion and position of the two cell types along the filament, leading to a morphologically heterogeneous population. Nevertheless, the pattern is controlled by biological mechanisms, because statistical studies have identified several intrinsic constraints leading to a characteristic architecture (Le Bail et al., 2008a). Furthermore, modeling of these development steps indicates that local positional information, corresponding to the cell identity of the two neighboring cells, is sufficient to account for most features of this early differentiation pattern (Billoud et al., 2008). More precisely, based on observations, it has been postulated that the presence of an R cell in the immediate neighborhood is necessary to allow E-to-R cell differentiation. However, spontaneous differentiation of an isolated R cell in the center of the filament is sometimes observed. This cannot be accounted for by the model and implies that local positional information, while being the main mechanism controlling cell differentiation in the early stages, operates in synergy with an integrated mechanism involving the perception of the overall body organization.

Figure 1.

Morphology of the E. ssiliculosus sporophyte. The body of the E. siliculosus sporophyte is composed of two main parts: (1) the prostrate body attached to the substratum, corresponding to the vegetative phase; and (2) the upright body, corresponding to filaments growing vertically in seawater and ultimately differentiating sporangia. The prostrate body (PB) originates from germinating zygotes (or mitospores or unfertilized gametes; A), which produce a uniseriate filament composed of two cell types (B): E cells located at the apices and R cells at the center. About 10 d after germination (dag), the primary filament differentiates secondary prostrate axes (C). Upright filaments (UF) differentiate from the prostrate body, and these are composed of squared, large cells (D), ultimately developing sporangia (E).

Despite the absence of characterized algal mutants impaired in phytohormone biosynthesis or signaling, several types of phytohormones (auxins, cytokinins, and abscisic acid) have been reported to be present in brown algae and to interfere with their development (for review, see Tarakhovskaya et al., 2007). Thus, we sought to investigate the possible role of phytohormones in the development of E. siliculosus.

In this paper, we present data that suggest that auxin plays a role as a signaling molecule controlling the progression of development in this macroalga, and we address the issue of its conservation in eukaryotes, a topic of increasing interest in the plant community (Lau et al., 2008, 2009).

RESULTS

Presence of Auxin Compounds in E. siliculosus and Possible Metabolic Pathways

Axenic filaments of E. siliculosus sporophytes were collected, and the levels of several auxin compounds were measured by both liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Table I shows that E. siliculosus contains low but significant amounts of auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), indole-3-carboxylic acid (ICA), and indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), with IAA being the most abundant (3.6 ng g−1). No other free indoles (especially IAA catabolites, 4-chloroindole-3-acetic acid, indole-3-butyric acid [IBA], and indole-3-acetamide [IAM]) were detected in algal tissues. In addition, alkaline hydrolysis did not reveal any IAA conjugates, nor were any detected by direct measurement.

Table I. Auxin compounds detected in the E. siliculosus sporophyte tissues.

GC-MS, Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry; LC-MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; NQ, not quantified (detected below the level of quantification).

| Compound | CAS No. | LC-MS Transition |

LC-MS Level |

| GC-MS Transition | GC-MS Level | ||

| pg mg−1 | |||

| IAA | 87-51-4 | 190.09 → 130.07 | 3.66 ± 0.26 |

| 261.12 → 202.11 | 2.80 ± 0.32 | ||

| ICA | 771-50-6 | 176.07 → 118.07 | 0.59 ± 0.10 |

| 245.12 → 216.08 | NQ | ||

| IPA | 830-96-6 | 204.10 → 130.07 | NQ |

| 275.13 → 202.11 | 0.71 ± 0.16 |

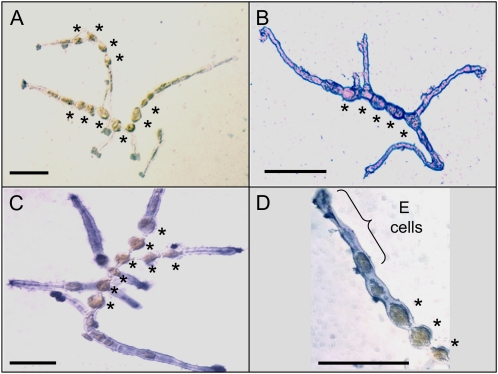

The localization of IAA within the filaments of E. siliculosus was determined by immunolocalization at the early stages of development. Compared with the negative control (Fig. 2A), immunolocalization of the α-tubulin protein showed homogeneous distribution within the whole filament (Fig. 2B). In contrast, IAA seemed to be preferentially localized in the apices of the filaments, with a lower concentration in the central cells (Fig. 2, C and D).

Figure 2.

Immunolocalization of IAA along the filaments of E. siliculosus. IAA was immunolocalized in very young sporophytic organisms (10 d old; blue-purple color; see “Materials and Methods”). A, Negative control corresponding to the omission of the primary antibody. B, α-Tubulin immunolocalization showing overall labeling. C, IAA immunolocalization showing the absence of IAA in the center of the filaments, corresponding mainly to R cells (stars). D, Detail of a filament apex after IAA immunolabeling, showing the absence of labeling in the central R cells. In these cells, the chloroplast is particularly visible as a golden brown area. Bars = 50 μm.

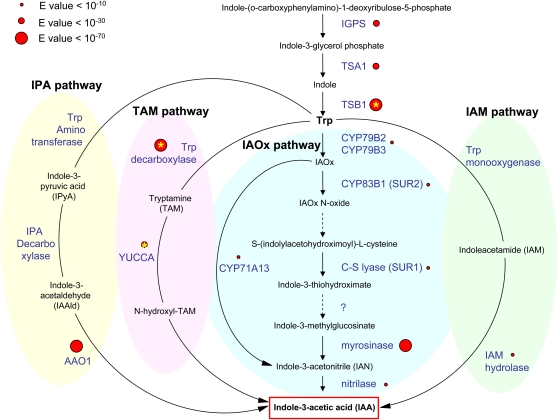

As IAA was present in E. siliculosus sporophytes, we investigated the possibility of a biosynthetic pathway operating in E. siliculosus. Knowledge of its genomic sequence allowed the search for homologs of genes encoding enzymes involved in IAA biosynthesis in land plants (for review, see Woodward and Bartel, 2005). Considering the phylogenetic distance between land plants and brown algae (Baldauf, 2008), the significance of E values was difficult to estimate. Nevertheless, Figure 3 and Table II show that homologs of several enzymes of the Trp-dependent pathway were found in the genome of this alga, with similar sequences forming in several cases a bidirectional best hit (BBH), which is a good indication of orthology (Overbeek et al., 1999). In addition, we searched for conserved functional domains by systematically comparing the sequence signatures in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) proteins with their counterparts in E. siliculosus (Table II).

Figure 3.

Indole compounds and putative enzymes involved in the synthesis of IAA in E. siliculosus. Substrates (black) and enzymes (blue) of the four biosynthetic pathways known or predicted in land plants (Woodward and Bartel, 2005; Nafisi et al., 2007; Sugawara et al., 2009) are presented. The indole product quantified in E. siliculosus sporophytes is framed in red. Putatively conserved enzymes inferred from genome sequence analysis of E. siliculosus are indicated by red dots. A yellow star indicates a BBH (see “Materials and Methods”).

Table II. Sequence conservation between Arabidopsis and E. siliculosus.

Proteins of Arabidopsis involved in the different steps of auxin synthesis and function were used to query the whole proteome of E. siliculosus. For each function, only the best-matching pairs are reported (the complete analysis results are available as Supplemental Table S1). The Ath in Esi column shows the BLAST E values for the search of Arabidopsis proteins within the E. siliculosus proteome. A second BLAST search was performed for each best-matching protein of E. siliculosus in the complete proteome of Arabidopsis. The E value for this reverse BLAST query is reported in the column Esi in Ath in cases when the best hit is the initial Arabidopsis protein (the sequence pair is a bidirectional best hit). The EST column shows whether an EST for the E. siliculosus sequence is known. The Conserved Domains column gives the domains shared by the E. siliculosus and Arabidopsis similar proteins, found by InterProScan in the following databases: Gene3D, HAMAP, Pfam, PIRSF, PRINTS, ProSite, Panther, Superfamily, and TIGR, for which entries begin with G3DSA, MF, PF, PIRSF, PR, PS, PTHR, SSF, and TIGR, respectively.

| Function | Arabidopsis UniProt Entry |

Protein in E. siliculosus | BLAST E Value |

EST | Conserved Domains | ||

| Accession No. | Identifier | Ath in Esi | Esi in Ath | ||||

| IAA biosynthesis | |||||||

| IGPS | P49572 | TRPC_ARATH | Esi0000_0449 | 5 × 10–36 | + | G3DSA:3.20.20.70; PF00218; PTHR22854:SF2 | |

| TSA1 | Q42529 | Q42529_ARATH | Esi0036_0051a | 8 × 10–41 | + | G3DSA:3.40.50.1100; MF_00131; MF_00133; PF00290; PF00291; PS00168; PTHR10314:SF3; SSF51366; SSF53686; TIGR00262; TIGR00263 | |

| TSB1 | Q0WUI8 | Q0WUI8_ARATH | Esi0036_0051a | 1 × 10–137 | 4 × 10–137 | ||

| Trp decarboxylase | Q8RY79 | TYDC1_ARATH | Esi0099_0045 | 4 × 10–94 | 1 × 10–88 | + | G3DSA:1.20.1340.10; G3DSA:3.40.640.10; G3DSA:3.90.1150.10; PF00282; PR00800; PTHR11999:SF11; SSF53383 |

| YUCCA | Q9LMA1 | FMO1_ARATH | Esi0350_0023 | 1 × 10–46 | 1 × 10–48 | + | G3DSA:3.50.50.60; PIRSF000332; PTHR23023:SF4; SSF51905 |

| CYP79B2/3 | Q501D8 | C79B3_ARATH | Esi0063_0068 | 7 × 10–14 | + | G3DSA:1.10.630.10; PF00067; PR00385; PR00463; PS00086; PTHR19383:SF143; SSF48264 | |

| CYP71A13 | O49342 | C71AD_ARATH | Esi0063_0067 | 3 × 10–17 | + | G3DSA:1.10.630.10; PF00067; PR00385; PR00463; PS00086; PTHR19383:SF143; SSF48264 | |

| CYP83B1 (SUR2) | O65782 | C83B1_ARATH | Esi0063_0067 | 1 × 10–24 | |||

| C-S lyase (SUR1) | Q9SIV0 | Q9SIV0_ARATH | Esi0002_0157 | 2 × 10–20 | + | G3DSA:3.40.640.10; PF00155; PR00753; SSF53383; PTHR11751 | |

| Myrosinase | P37702 | MYRO_ARATH | Esi0176_0045 | 2 × 10–81 | + | G3DSA:3.20.20.80; PF00232; PR00131; PTHR10353:SF6; SSF51445 | |

| Nitrilase | P32961 | NRL1_ARATH | Esi0003_0068 | 9 × 10–15 | + | G3DSA:3.60.110.10; PF00795; PTHR23088; PS50263; SSF56317 | |

| AAO1 | Q7G193 | ALDO1_ARATH | Esi0058_0108 | 6 × 10–107 | + | G3DSA:1.10.150.120; G3DSA:3.10.20.30; G3DSA:3.30.365.10; G3DSA:3.30.390.50; G3DSA:3.30.465.10; G3DSA:3.90.1170.50; PF00111; PF00941; PF01315; PF01799; PF02738; PF03450; PS00197; PS51085; PS51387; PTHR11908; SSF47741; SSF54292; SSF54665; SSF55447; SSF56003; SSF56176 | |

| IAM hydrolase | Q9FR37 | Q9FR37_ARATH | Esi0082_0071 | 9 × 10–14 | + | PS00571; PTHR11895 | |

| TAA1 | Q9SB62 | Q9SB62_ARATH | None | ||||

| IAA metabolism | |||||||

| ILL1 | P54969 | ILL1_ARATH | None | ||||

| ILL2 | P54970 | ILL2_ARATH | None | ||||

| ILL3 | O81641 | ILL3_ARATH | None | ||||

| ILL4 | O04373 | ILL4_ARATH | None | ||||

| ILL5 | Q9SWX9 | ILL5_ARATH | None | ||||

| ICR1 | Q8LE98 | ICR1_ARATH | None | ||||

| ICR2 | Q9ZQC5 | ICR2_ARATH | None | ||||

| ICR3 | Q9LSS5 | ICR3_ARATH | None | ||||

| ACX1 | Q9ZQP2 | ACO12_ARATH | Esi0493_0006 | 2 × 10–101 | 6 × 10–102 | + | G3DSA:1.10.540.10; G3DSA:1.20.140.10; G3DSA:2.40.110.10; PF01756; PF02770; PTHR10909:SF11; SSF47203; SSF56645 |

| ACX4 | Q96329 | ACOX4_ARATH | Esi0005_0083 | 2 × 10–36 | + | G3DSA:1.10.540.10; G3DSA:1.20.140.10; G3DSA:2.40.110.10; PF00441; PF02770; PF02771; PS00072;PS00073; PTHR10909:SF10; SSF47203; SSF56645 | |

| AIM1 | Q9ZPI6 | Q9ZPI6_ARATH | Esi0063_0042 | 2 × 10–93 | 3 × 10–82 | + | G3DSA:1.10.1040.10; G3DSA:3.40.50.720; G3DSA:3.90.226.10; PF00378; PF00725; PF02737; PTHR23309; SSF48179; SSF51735; SSF52096 |

| IAR1 | Q9M647 | IAR1_ARATH | Esi0005_0095 | 1 × 10–12 | 6 × 10–16 | − | PF02535 |

| IAR4 | Q8H1Y0 | ODPA2_ARATH | Esi0122_0080 | 3 × 10–86 | 6 × 10–91 | + | PF00676; PTHR11516:SF4; SSF52518 |

| KAT1 | Q8LF48 | THIK1_ARATH | Esi0320_0011 | 1 × 10–80 | 2 × 10–14 | + | PF00108; PF02803; PIRSF000429; PS00098; PS00099; PS00737; PTHR18919:SF15; SSF53901; TIGR01930 |

| PEX5 | O82467 | O82467_ARATH | Esi0002_0040 | 2 × 10–62 | + | PTHR10130 | |

| PEX6 | Q8RY16 | O48676_ARATH | Esi0016_0105 | 2 × 10–94 | 1 × 10–65 | + | G3DSA:1.10.8.60; G3DSA:3.40.50.300; PF00004; PS00674; PTHR23077:SF9; SM00382; SSF52540 |

| PEX7 | Q9XF57 | Q9XF57_ARATH | Esi0120_0004 | 8 × 10–41 | − | G3DSA:2.130.10.10; PF00400; PR00320; PS00678; PS50082; PS50294; PTHR22850:SF4; SM00320; SSF50978 | |

| PEX14 | Q9FE40 | Q9FE40_ARATH | Esi0063_0064 | 9 × 10–9 | 4 × 10–8 | + | PF04695 |

| IBR3 | Q67ZU5 | Q67ZU5_ARATH | Esi0223_0017 | 1 × 10–106 | + | G3DSA:1.10.540.10; G3DSA:1.20.140.10; G3DSA:2.40.110.10; PF00441; PF02770; PF02771; PTHR10909; SSF47203; SSF56645 | |

| IAA transport | |||||||

| PIN1-7 | 6 components | None | |||||

| MDR1 | Q9ZR72 | AB1B_ARATH | Esi0109_0017 | 0 | + | PF00005; PF00664; PS00211; PS50893; PS50929; SM00382; PTHR19242:SF96; SSF52540; SSF90123 | |

| MDR1 | Q9LJX0 | AB19B_ARATH | Esi0109_0017 | 0 | |||

| BIG | Q9SRU2 | Q9SRU2_ARATH | Esi0038_0043 | 1 × 10−38 | 3 ×10−38 | − | PF00569; PS01357;PS50135; PS51157; PTHR21725; SM00291 |

| AXR4 | Q9FZ33 | AXR4_ARATH | None | ||||

| Auxin signaling: SCF | |||||||

| TIR1 | Q8RWQ8 | FBX14_ARATH | Esi0053_0061 | 2 × 10–11 | − | ||

| ASK1 | O65674 | ASK12_ARATH | Esi0046_0039 | 5 × 10–38 | 9 × 10–35 | + | G3DSA:3.30.710.10; PF01466; PF03931; PIRSF028729; PTHR11165; SM00512; SSF54695; SSF81382 |

| Cullin | Q8LGH4 | Q8LGH4_ARATH | Esi0207_0055 | 0 | 0 | + | G3DSA:1.10.10.10; G3DSA:1.20.1310.10; G3DSA:4.10.1030.10; PF00888; PF10557; PS01256; PS50069; SM00182; SSF46785; SSF74788; SSF75632; PTHR11932:SF22 |

| Cullin | Q9C9L0 | Q9C9L0_ARATH | Esi0245_0022 | 0 | 0 | + | G3DSA:1.10.10.10; G3DSA:1.20.1310.10; PF00888; PF10557; PS50069; PTHR11932:SF23; SM00182; SSF46785; SSF74788; SSF75632 |

| RBX1A | Q940X7 | RBX1A_ARATH | Esi0079_0058 | 6 × 10–26 | 3 × 10–26 | + | G3DSA:3.30.40.10; PF00097; PS50089; PTHR11210:SF2; SM00184; SSF57850 |

| RCE2 | Q9ZU75 | UB12L_ARATH | Esi0007_0140 | 1 × 10–48 | 2 × 10–48 | + | G3DSA:3.10.110.10; PF00179; PS00183; PS50127; PTHR11621:SF17; SM00212; SSF54495 |

| SGT1b | Q9SUT5 | Q9SUT5_ARATH | Esi0014_0174 | 1 × 10–25 | + | G3DSA:1.25.40.10; G3DSA:2.60.40.790; PF04969; PF05002; PS50005; PS50293; PS51048; PS51203; PTHR22904:SF10; SM00028; SSF48452 | |

| ECR1 | O65041 | UBA3_ARATH | Esi0069_0046 | 1 × 10–62 | 1 × 10–62 | + | G3DSA:3.40.50.720; PF00899; PS00865; PTHR10953:SF6; SSF69572 |

| ULA1 | P42744 | ULA1_ARATH | Esi0358_0003 | 7 × 10–34 | + | G3DSA:3.40.50.720; PTHR10953; SSF69572 | |

| CSN5 | Q9FVU9 | CSN5A_ARATH | Esi0055_0013 | 3 × 10–47 | 4 × 10–47 | + | PF01398; PTHR10410:SF6; SM00232; SSF102712 |

| CAND1 | O64720 | O64720_ARATH | Esi0168_0022 | 0 | 0 | + | G3DSA:1.25.10.10; PF08623; PTHR12696; SSF48371 |

| Transcription factors | |||||||

| Aux/IAA | 29 family members | None | |||||

| ARF9 | Q9XED8 | ARFI_ARATH | Esi0079_0037 | 7 × 10–9 | − | ||

| ARF10 | Q9SKN5 | ARFJ_ARATH | Esi0079_0037 | 2 × 10–6 | |||

| ARF11 | Q9ZPY6 | ARFK_ARATH | Esi0079_0037 | 1 × 10–5 | |||

| ARF | 20 other family members | None | |||||

In E. siliculosus, a single gene encodes a long protein that corresponds to both TSA1 (N-terminal half) and TSB1 (C-terminal half).

Among the enzymes involved in the terminal steps of IAA biosynthesis, myrosinase and AAO1 displayed significant similarities with E. siliculosus proteins. However, the similarity with nitrilase and CYP71A13 was lower. Enzymes synthesizing Trp (IGPS, TSA1, and TSB1) also seemed well conserved, and more interestingly, Trp decarboxylase and YUCCA of the TAM pathway had homologs in the E. siliculosus genome that were supported by a BBH. The cytochrome P450 monooxygenases CYP79B2, CYP79B3, and CYP83B1 were moderately conserved. Less conservation was observed for the enzymes of two additional alternative pathways, the IPA and the IAM pathways. In agreement with the lack of indole-3 pyruvic acid in E. siliculosus filaments, no reliable homologs of Trp aminotransferases (TAA1-like genes; Stepanova et al., 2008) or of IPA decarboxylase were found. The lack of Trp monooxygenase homologs corroborates the absence of IAM in E. siliculosus. However, a putative IAM hydrolase (AMI1 homolog) was found at a low significance level. Altogether, these data support the existence of a Trp-dependent IAA biosynthesis pathway in E. siliculosus, with the TAM and IAOx subpathways being the most probable ones (Fig. 3).

Very low conservation with IAA conjugation enzymes having sugar or amino acid moieties (GH3 family, ILL, ICR, ILR; Table II) was found, which is in accordance with the lack of detectable IAA-conjugated compounds in the E. siliculosus extracts. In contrast, the machinery used for IAA conversion into IBA in the peroxisome of land plants is significantly represented in E. siliculosus, at least at the genome level.

An in silico search for homologs of IAA transporters in E. siliculosus revealed a lack of conservation of the auxin efflux transporter PIN and the auxin influx transporter AUX1. The same result was obtained for the ABP1 glycoprotein located in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. On the contrary, the multidrug resistance protein ABCB19 (also named MDR1, MDR11, and PGP19; Titapiwatanakun et al., 2009) had two matches with very significant similarity (BLAST P = 0). In E. siliculosus, a large family codes for these transporters (103 members), and 18 of them display significant similarity with ABCB19 (P < 10−30; Table II; Supplemental Table S1).

Finally, despite the fact that a complete suite of Cullin, ASK1, and RUB1-associated proteins (SCF complex) and its regulators (CAND1, SGT1b) seemed to be conserved, no IAA-specific F-box protein TIR1 homolog was detected (Table II). Furthermore, no significant similarity was found with the transcription factors of the auxin-response factor (ARF) and the AUX/IAA families.

Auxin Modifies the Branching Pattern in E. siliculosus Sporophytes

The effect of auxin on the growth and development in E. siliculosus was tested at different stages of its life cycle. E. siliculosus development follows a complex heteromorphic haplodiploid life cycle (Müller, 1967). Diploid sporophytes produce both meiospores (from a meiotic event) and mitospores, which ensure vegetative propagation. Mobile meiospores generate independent male or female gametophytes (dioecism), which, once sexually mature, produce isogamous mobile gametes that fuse in the environment. Nevertheless, both female and male unfertilized gametes are able to germinate and generate an organism with the same morphology as the diploid sporophyte. This haploid organism does not produce cells that can fuse, and it is called a parthenosporophyte.

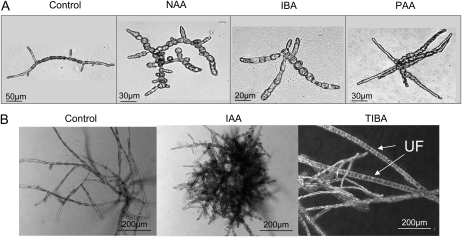

Auxin compounds had no effect on meiospore germination. In contrast, the application of IAA (50 μm) on mitospores prevented germination by 100%. Partial inhibition of germination (60%) was obtained with 2-methoxy-3,6-dichlorobenzoic acid (dicamba; 50 μm), and the spores that did germinate showed severe growth inhibition. Concentrations of IAA and dicamba 1 and 2 orders of magnitude lower had no effect on germination. The other auxin compounds tested altered the development of young sporophytes without affecting their growth. Application of 50 μm 1-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA) at early stages modified both cell types and cell positions along the filament and filament polarization (Fig. 4A). While control specimens were composed of R cells clustered in the center of the filament and E cells in the apices, treated organisms displayed abnormal cell shapes. Furthermore, overall disorganization of the filament architecture was observed, with the initiation of numerous branching points and unusual localization of E cells. Similar effects were observed with IBA (50 μm), but at a weaker intensity, and with 2-phenyl-acetic acid (PAA; 50 μm), which produced very long cells in the apices (Fig. 4A). No modification was observed in response to 4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, and the auxin transport inhibitors 2,3,5-triiodobenzoic acid (TIBA) and N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA). Therefore, while IAA and dicamba mainly inhibited germination and growth, NAA, IBA, and PAA modified the architecture of E. siliculosus at early developmental stages by changing cell patterning, filament polarization, and inducing numerous ectopic branches.

Figure 4.

Effects of auxin compounds on the development of E. siliculosus sporophytes. Different auxin compounds were applied to E. siliculosus spores at germination time (A) or 20 d after germination (B). The effects on morphology were observed 2 weeks later. Application of 50 μm NAA on mitospores resulted in the differentiation of cells with an abnormal shape. Growth polarity was also affected. Application of IBA led to a similar effect, yet weaker, and PAA produced organisms with very long terminal cells and an altered branching pattern. When auxin compounds were added later during development (at 20 d after germination), the observed effects were different. While IAA increased the production of prostrate filaments, TIBA induced the differentiation of upright filaments (UF) earlier than in the control.

When applied at later stages (20 d after germination), 50 μm IAA induced an increase in the rate of prostrate branching compared with controls, and 50 μm TIBA induced earlier and more frequent differentiation of upright reproductive filaments (Fig. 4B).

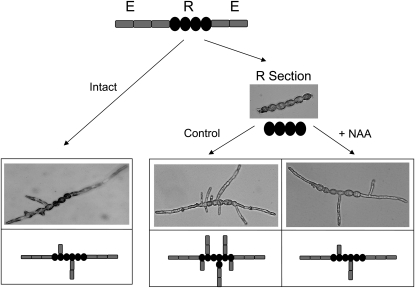

Because IAA seemed localized preferentially in the apical E cells, we investigated the impact of E cells on central R cell fate, and vice versa, in the presence and absence of auxin. Thus, E cell extremities were ablated and separated from the central R cells, and each section was grown in artificial seawater (ASW). E and R sections were grown for 1 week with or without IAA or NAA (5 μm each, R sections only), and the morphology of the resulting organisms was observed 1 week later. For the E sections, spontaneous differentiation of R cells in the center of the section was observed, thereby reconstituting filament organization similar to controls without ablation (data not shown). In the R sections, E cells regenerated at the extremities of the sections (Fig. 5, control), both in the absence or presence of exogenous auxins. Thus, both E and R sections were able to readjust their differentiation program to regenerate the missing cells and reform a normally structured filament. However, the branching pattern observed from the R sections differed depending on the supply of NAA (Fig. 5). On average, 4.6 lateral branches were produced on the primary filaments in the control medium, while 1.8 were produced in the presence of NAA, which is similar to the branching rate of intact filaments at the same stage. Therefore, when added at the ablation time, NAA significantly inhibited lateral branching (χ2 test, P = 1.6 × 10−9). IAA showed similar but weaker effects (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Impact of NAA on branching. Pieces of filaments containing only R cells were isolated and grown in the presence or absence of 5 μm NAA (right). The developmental pattern of the filaments was observed 1 week after ablation, and the number of secondary filaments was counted (see text) and compared with the number obtained from intact filaments (left).

In all these experiments, differences between the response to IAA and NAA were observed. These molecules have different physicochemical properties, and their transport or diffusion in the organism is known, at least in land plants, to require different processes (Yamamoto and Yamamoto, 1998; Woodward and Bartel, 2005). A lower penetration of exogenous IAA compared with NAA through the E. siliculosus cell wall may explain why NAA had more effects on E. siliculosus development. Moreover, the sensitivity of cells to IAA may be higher, explaining why spores, which lack cell walls, died upon application of IAA while they germinated with NAA at the same concentration.

Morphogenetic Mutants Are Altered in the Auxin Perception and Signaling Pathway

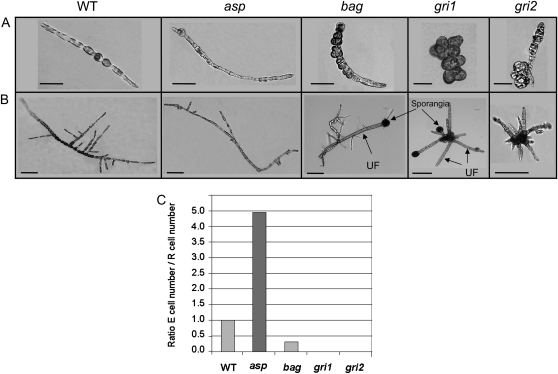

To demonstrate the role of auxin in the developmental pattern of E. siliculosus sporophytes, we analyzed four mutants impaired in cell differentiation generated by UV-B mutagenesis on mitospores. The mutant asparagus (asp) looked quite similar to the wild type (Fig. 6A), but both its branching pattern and its cell distribution were different. Fewer secondary filaments were produced (Fig. 6B), and the E cell proportion measured between the two- and 10-cell stages was higher than in the wild type (Fig. 6, A and C), suggesting that the E-to-R cell differentiation process had been altered. On the other hand, the mutants baguette (bag), grissini1 (gri1), and gri2 developed a prostrate body very different from the wild type (Fig. 6). All three mutants displayed altered growth polarity, with cells dividing in several axes, especially in gri1, where the body looked like a callus (Fig. 6A). The E cell identity was lost in gri1 and gri2 (both 0% E cells) and was strongly reduced in bag (24% E cells; Fig. 6, A and C). Their developmental program was characterized by an extremely early emergence of upright filaments in the bag and gri1 mutants and by a high abundance of secondary prostrate filaments in gri2 (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Morphology of the morphogenesis mutants. Phenotypes of the four mutants asp, bag, gri1, and gri2 compared with the wild type (WT). The phenotypes are shown 5 (A) and 15 (B) d after germination. UF, Upright filaments. Bars = 15 μm in A and 50 μm in B. C, Proportion of R cells. Both R cells and E cells were counted in 36 sporophytes from the two- to the 10-cell stage, and the ratio of the total number of each cell type was calculated (no. of cells > 200).

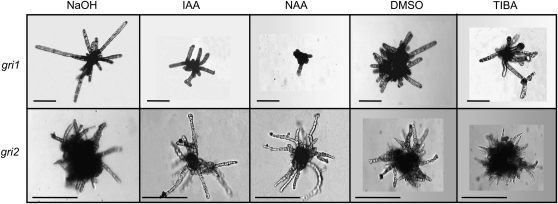

To investigate whether these morphological alterations were related to auxin metabolism, these mutants were treated with 50 μm IAA, NAA, and TIBA. Modifications of the developmental pattern were observed in gri1 and gri2 mutants only. While in gri1, NAA and, to a lesser extent, IAA reduced the emergence of upright filaments, in gri2, less and longer secondary prostrate filaments grew (Fig. 7). TIBA slightly increased the differentiation of sporangia in gri1, while it had no noticeable effects in gri2. Therefore, gri1 and gri2 were able to respond to auxin, in contrast to asp and bag, which were insensitive to it.

Figure 7.

Response of E. iliculosus morphogenesis gri1 and gri2 mutants to auxin compounds. Fifty micromolar IAA, NAA, and TIBA were applied to gri1 and gri2 cultures. The morphology was observed 14 d later and compared with the control cultures (10−4 m NaOH for IAA and NAA and 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] for TIBA). In gri1, upright branching was reduced upon application of IAA and inhibited in response to NAA. In response to TIBA, no significant change in morphology was observed. In gri2, IAA and NAA reduced the number of short secondary filaments and induced the growth of longer filaments. Bars = 50 μm.

Quantifying the amount of auxin in these mutants would be helpful to better decipher the link between the phenotype and auxin metabolism. However, because gri1 and gri2 grew slowly, the amount of biological material was too small to quantify IAA in them. Therefore, we searched for auxin-inducible genes, which could be used as auxin-reported genes. A small-scale microarray experiment was performed with RNAs extracted from tissues treated with 50 μm NAA for 30 min or 3 h. Out of 24 ESTs initially selected from the microarray data as being either up-regulated or down-regulated by the NAA treatment, the overexpression of only one, named EsGRP1, was confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR.

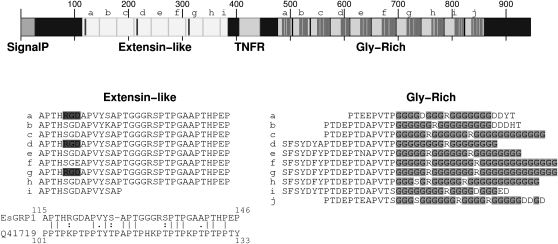

PCR amplification of 3 kb upstream of the EsGRP1 EST (located in the 3′ untranslated region) led to the identification of an open reading frame. In the deduced protein sequence, two main domains shared similarity with extensin and Gly-rich proteins (Fig. 8). The central part of the protein sequence contained a series of 8.5 adjacent repeats of 32 amino acids sharing similarity with extensin from Zea diploperennis (UniProt-KB accession no. Q41719; lalign local alignment, E = 1.5 × 10−34). In the C-terminal part of the sequence, 10 repeated Gly-rich sequences were clustered, separated by several hydrophilic sequences of eight to 19 amino acids. In land plants, extensins are Hyp-rich proteins present in the extracellular matrix, where they are thought to play a role in plant cell wall stiffness (Kieliszewski and Lamport, 1994), and Gly-rich proteins are secreted proteins involved in adhesion and extension of differentiating vascular cells (Ringli et al., 2001).

Figure 8.

Structure of the EsGRP1 protein. Four functional domains are identified in the peptide sequence of EsGRP1 predicted from the genome sequence. The signal peptide (amino acids 1–27) can be used to address the protein to the membrane. The extensin-like domain (amino acids 115–384) is made of 8.5 repeats (shown as boxes a–i) of a 32-amino acid module. Every three modules, the sequence contains an RGD motif (marked as vertical lines). The complete sequence of the repeats is shown below, with the RGD motif shaded. The alignment of the first module with one of the eight repeats of the Pro-rich extensin motif of Z. diploperennis (Q41719) shows a partial sequence similarity. The TNFR region (amino acids 406–444) matches with Prosite pattern PS00652, which is found in tumor necrosis factors and nerve growth factors. However, in tumor necrosis factor and nerve growth factor proteins, this pattern is present in three or four copies, usually located in the N-terminal part of the protein, which is not the case in EsGRP1. The Gly-rich region (amino acids 477–860, with the Gly residues marked as vertical lines) is made of 10 approximate repeats (boxes a–j). The complete sequence of this region is shown below the map, with the Gly residues shaded. Each repeat can be divided into two parts: the first eight to 19 amino acid residues correspond to a complex pattern, which can appear in more or less complete forms; the remaining 17 to 27 amino acid residues are mainly Gly.

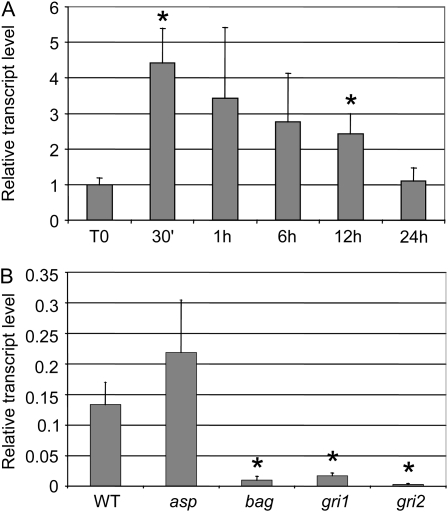

A kinetics study in response to NAA showed that the transcript level of EsGRP1 was more than four times higher than the control 30 min after the addition of NAA, and it slowly decreased to its basal level after 24 h (Fig. 9A). In the mutant asp, the EsGRP1 transcript level was higher than in the wild type, while levels in bag, gri1, and gri2 mutants were significantly reduced (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9.

Transcript levels of EsGRP1. The levels of transcripts of EsGRP1 were quantified by real-time reverse transcription-PCR on three independent biological replicates. Each transcript level was normalized to EsEF1α transcripts, as recommended by Le Bail et al. (2008b), and averaged (sd indicated). Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 with a t test. A, In response to NAA. Mature sporophytes were incubated for 24 h in 50 μm NAA, and tissues were collected at different times. After averaging, the transcript levels were normalized to the T0 value. B, In morphological mutants. WT, Wild type.

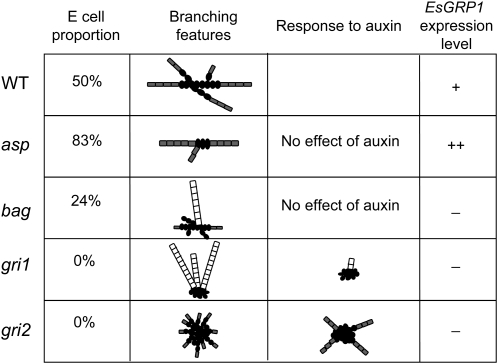

A summary of the data obtained with the mutants is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Summary of the phenotypic characterization of the mutants asp, bag, gri1, and gri2. The mutant phenotypes are summarized in terms of the proportion of E cells, branching features, response to auxin, and EsGRP1 transcript levels. For the branching features, note that it describes both prostrate filaments (gray) and upright filaments (white). R cells are shown as black ovals. WT, Wild type.

DISCUSSION

Role of Auxin in E. siliculosus Development

Some studies have already investigated the role of auxin in brown alga development. At the embryo stages, exogenous application of IAA has been shown to reduce cell polarization in Fucus vesiculosus (order Fucales) and to induce numerous ectopic rhizoid differentiations when grown in the dark (Basu et al., 2002). In this study, exogenous NAA also induced body polarity impairment and numerous ectopic branches when applied at the germination stage in E. siliculosus. Therefore, in both algal models, exogenous auxin applied before the division of the initial cell triggers general disorganization of the growing thallus.

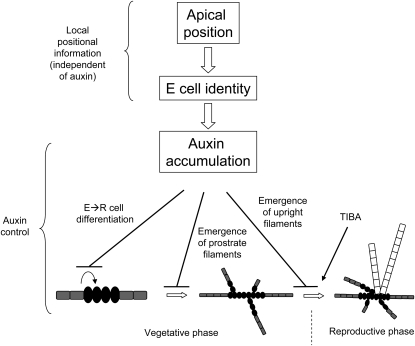

In our experiments, when auxin was applied later during the development of E. siliculosus, different developmental responses were observed. Because cells acquire either an E or an R identity immediately after the first division, we investigated the effects of auxin on these differentiated cells. Our approach of isolating R or E sections from the rest of the primary filament helped better understand how cell fate is dictated and how auxin may regulate morphogenetic patterns in early developmental stages. In normal growth medium, ablated R cell fragments were able to reconstitute the initial filament with the correct developmental pattern. More specifically, in response to ablation, the resulting apical R cell reinitiated cell division toward both extremities of the filament while maintaining initial growth polarity. In addition, the daughter cells acquired the E cell identity. Interestingly, in intact filaments, R cells divide very rarely at this stage, and the differentiation of R to E cells is never observed (Billoud et al., 2008; Le Bail et al., 2008a). Therefore, this indicates that following ablation, R cells modify their identity and behavior to follow the intrinsic developmental program. In the brown alga Pelvetia compressa (order Fucales), ablation experiments at the two-cell embryo stage showed that cell lineage is already established at this stage (Kropf et al., 1993). However, the identity of the cell seems to depend on molecular determinants present in its cell wall, because additional experiments performed on the brown alga Fucus spiralis show that remnants of cell wall from the ablated cell dictate cell fate to the new cell growing in contact with it (Berger et al., 1994). In E. siliculosus, R cell fragments were cut from within a larger R zone, thereby precluding contact with remnant cell walls from excised E cells. Therefore, cell fate in E. siliculosus is completely independent of the presence of E cell determinants, contrary to what has been observed in the Fucales. These differences in the mechanisms and determinants of cell fate may be related to differences in body architecture between the species, as both Fucus and Pelvetia develop three-dimensionally growing thalli while Ectocarpus is composed of uniseriate filaments. This determination process was independent of the addition of exogenous auxin and may rely on local positional information as suggested by Billoud et al. (2008; Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Model for the role of auxin in the development of the E. siliculosus sporophyte. Cells positioned at the apices of the filament acquire the E identity. A higher concentration of auxin is present in these cells, which prevents them from differentiating into R cells and/or inducing branching. As the filament grows, subapical E cells get localized farther from the apex and perceive lower auxin concentrations, which progressively induce their differentiation into R cells as well as branching. Later, auxin maintains its control on the progression of the life cycle by negatively controlling the emergence of the upright filament and thereby the shift to the reproductive phase. Auxin control would then depend on active transport, allowing the apices to maintain control on distant tissues.

In contrast, auxin seems to negatively control the progression in the developmental program. At the early prostrate stage, ablated R cell fragments induced the growth of more branches than in intact filaments. Addition of NAA to these fragments resulted in reduced branching, suggesting that auxin inhibits branching in the intact filament. In situ immunolocalization experiments showed that actively proliferating apices of the filaments did have higher concentrations of IAA. Similar results have been obtained in filaments of the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens, where the expression of GH3::GUS and DR5::GUS transgenes indicates higher concentrations of auxin in the young, actively growing cells of the protonemal filaments (Bierfreund et al., 2003), similarly located at the apices (Cove et al., 2006). Therefore, a possible scenario in agreement with the data from the ablation experiment is that, in an intact filament, there is an IAA gradient that reaches its maximum at both extremities of the filament, where E cells are located. As the organism grows, central cells move farther from the IAA source, progressively differentiate into R cells in response to the decrease in IAA concentration, and ultimately initiate branching. Hence, only the apical position and a high IAA content in E cells would result in the developmental pattern observed in culture, as proposed in the model in Figure 11. The analysis of mutants provides support for this scenario, where the higher the percentage of E cells, the higher the EsGRP1 transcript levels are and the lower the rate of emergence of prostrate filaments is. This is well illustrated in the mutant asp, which contains 83% of E cells, overexpresses EsGRP1, and displays a lower branching rate, contrary to gri2, which has an extremely high number of secondary axes borne on a callus body made of only R cells expressing a very low level of EsGRP1 transcripts (Fig. 10). In response to auxin, gri2 decreases its rate of branching, providing evidence that auxin negatively controls hyperbranching of prostrate filaments. The asp mutant was insensitive to the auxin treatment, possibly due to overinduction of its auxin signaling pathway (potentially due to an overaccumulation of IAA), which is concordant with the overexpression of EsGRP1.

At mature vegetative stages (approximately 20–40 d after germination), addition of exogenous auxin on wild-type cultures triggered an increase in the emergence of prostrate filaments, while addition of TIBA increased the emergence of upright filaments. This is an indication that auxin may negatively control the transition from the branching of prostrate filaments to the branching of upright filaments and that this effect relies on auxin transport within the prostrate body (Fig. 11). Again, the observation of mutants supports this hypothesis. The two mutants bag and gri1 displayed a pronounced reduction in the vegetative phase, since upright filaments and sporangia differentiate as soon as the prostrate body is composed of a few cells (10 d old). Most or all of the cells of prostrate bodies are of the R type, which again was correlated with a reduction in EsGRP1 transcript levels. While bag was insensitive to auxin treatment, gri1 responded by decreasing the number of upright filaments, somehow reverting the effect of the mutation by slowing down the emergence of upright filaments (Fig. 11). The absence or the weak effect of TIBA on the development of these mutants may be due to the fact that they were still in an early growth stage, despite their advanced morphological features.

Altogether, these results support a role of auxin as an inhibitor of the progression of the developmental programs in E. siliculosus, as illustrated in our model in Figure 11. Interestingly, in the brown alga Laminaria japonica, which is phylogenetically closely related to the Ectocarpales (Phillips et al., 2008), auxin levels are lower in the reproductive tissues than in the vegetative tissues, and the formation of sori is delayed in response to 50 μm IAA (Kai et al., 2006). This illustrates that the developmental role of auxin observed in E. siliculosus may be common to other complex brown algae.

Synthesis and Transport of Auxin in E. siliculosus

The model illustrated in Figure 11 is based on a high concentration of IAA in the apical E cells and on a diffusion of IAA along the primary filament in early developmental stages relayed by active transport toward the more distant tissues in later stages.

The synthesis of auxin by brown algae is an old and controversial issue. Despite the fact that several phytohormones have been shown to be present in brown algae (for review, see Tarakhovskaya et al., 2007), studies on nonaxenic cultures raised the concern that auxin detected in algal extracts was of bacterial origin (Bradley, 1991). Here, using a combination of liquid chromatography, gas chromatography, and mass spectrometry on axenic cultures, we showed that IAA was present in low, but significant, amounts in E. siliculosus sporophytes. IPA and ICA, likely to be decarboxylated degradation products of IAA (Ljung et al., 2002), were also detected. The levels of IAA quantified in E. siliculosus were similar to those found in the brown alga F. vesiculosus (Basu et al., 2002). No auxin-associated compound was detected other than these three. They are either absent from E. siliculosus cells or only transiently accumulated, in which case they will probably remain elusive until an IAA biosynthesis mutant is identified. The identification of homologs of IAA biosynthesis enzymes suggests that other auxin-associated compounds are transiently present. Accordingly, we identified sequences in the E. siliculosus genome with similarities to several enzymes of the TAM and IAOx Trp-dependent IAA biosynthesis pathway.

Unlike Arabidopsis, which maintains about 99% of its IAA in conjugated forms (Woodward and Bartel, 2005), no IAA conjugate was detected in E. siliculosus sporophytes. This is in agreement with previous studies that have shown that brown algae do not store IAA compounds as amino acid or sugar conjugates (Basu et al., 2002). Likewise, no significant conservation of the conjugation enzymes (IAA glucosyltransferases, IAA aminotransferases, etc.) was detected in the genome. However, significant conservation of homologs of IBA-metabolic genes was observed, which may account for the conversion of IAA into IBA for storage in peroxisomes. However, these enzymes may not be specific to IBA transport and β-oxidation (Woodward and Bartel, 2005), as confirmed by the absence of a detectable level of IBA in E. siliculosus.

In summary, the E. siliculosus genome contains homologs of most genes involved in the Trp-dependent IAA biosynthesis TAM and IAOx pathways, suggesting that E. siliculosus synthesizes its own IAA. Our chemical data and genome analysis do not lend support to the hypothesis that IAA conjugates are synthesized and stored. Conversely, the detection of ICA and IPA supports an alternative hypothesis that has been proposed for photosynthetic organisms with simple architecture (Cooke et al., 2002), whereby IAA homeostasis is ensured by the regulation of IAA biosynthesis/degradation processes.

Tissue patterning in response to an IAA gradient raises the puzzling issue of how the gradient is established. Our survey of the E. siliculosus genome does not support the conservation of land plant IAA influx (AUX1) and efflux (PIN) proteins, which may participate in polarized transport. However, certain similarities with Arabidopsis remain. E. siliculosus possesses a putative homolog of BIG, a calossin-like family protein involved in the auxin control on PIN endocytosis (Paciorek et al., 2005). In addition, E. siliculosus has several ABCB efflux IAA transporters, which participate in the polarized transport of IAA and stabilize PIN1 (Friml, 2009; Titapiwatanakun et al., 2009). In E. siliculosus, the auxin transport inhibitor TIBA affected the late developmental stages. Similarly, in Fucus distichus, both TIBA and NPA were shown to alter the developmental pattern of the embryo by inducing branched rhizoids (Basu et al., 2002). However, the inhibitory effect of NPA and TIBA may not be strictly specific to PIN proteins, as these molecules act more generally on actin cytoskeleton dynamics, to which vesicle-mediated PIN recycling is particularly sensitive (Dhonukshe et al., 2008). Therefore, the simple architecture of E. siliculosus may be attributable to basic IAA diffusion from the apical IAA-synthesizing cells. The physicochemical characteristics of IAA are compatible with this type of diffusion process (Cooke et al., 2002), and in F. distichus, molecules as large as 10 kD are able to move through the embryonic cells in both directions along the polar axis (Bouget et al., 1998), providing evidence for symplastic transport in brown algae. Interestingly, E. siliculosus cells possess plasmodesmata (Charrier et al., 2008), which may allow auxin to freely diffuse from cell to cell. Alternatively, another, yet-to-be-identified type of IAA efflux transporter that has no sequence conservation with PIN proteins may have evolved in brown algae.

Whatever the mode of transport of IAA through the filament, our data show that E. siliculosus responds to it, both in terms of morphology and gene expression. However, the signaling mechanism does not appear to be similar to the mechanism known in land plants (Parry and Estelle, 2006; Kepinski, 2007). The ubiquitous proteins of the SCF complex are well conserved, but we could not identify any specific component of the auxin-responsive machinery in E. siliculosus. In particular, we did not find any transcriptional inhibitor similar to AUX/IAA. Their specific targeting factor, namely a protein similar to the F-box partner TIR1 (or AFB), is also lacking. Therefore, the control of gene expression in response to IAA in E. siliculosus must differ from what is known in land plants. The mechanism alone may be conserved, relying on different transcriptional inhibitors that would be recognized by an IAA-protein complex able to address them to degradation. It is possible that the primary sequence and/or three-dimensional structure of the transcription and targeting factors differ extensively from known proteins, as long as the key features of the auxin-regulating model are conserved. In particular, it would be expected that both the transcription factor and the targeting factor differ from their counterparts in land plants and coevolve so as to maintain their interaction. Alternatively, the mechanism of gene activation by auxin may be unique to a given set of species, along with a specific pathway and machinery. This could be the case for the whole Heterokontophyta phylum, as genomic studies performed on unicellular heterokonts, namely two diatoms (Armbrust et al., 2004; Bowler et al., 2008), show that there is no conservation of IAA signaling genes known in land plants. This suggests that an alternative signaling pathway exists in these microalgae (Lau et al., 2009). However, the two possible auxin-signaling pathways proposed for these species involve the proteins ABP1 and IBR5, for which there is no close relative in E. siliculosus.

In conclusion, previous studies on E. siliculosus morphogenesis showed that very local positional information, corresponding to cell-cell recognition, could be a reliable mechanism that would account for most of the developmental patterns of the early filament (Billoud et al., 2008). However, this model required an additional mechanism to completely explain morphogenesis. Results presented in this study provide support for auxin-mediated, long-range control of the developmental patterning in the brown alga E. siliculosus. This developmental patterning is based on the same cellular responses as in land plants: cell proliferative competence relative to the highest concentrations of auxin and negative branching control preventing progression in the life cycle. In addition, we showed that the genome of this alga contains elements that are similar to the IAA biosynthetic machinery operating in land plants. The presence of IAA in brown algae, coupled with the lack of conservation of IAA transport and signaling pathways in E. siliculosus, sketches the outline of an evolutionary scenario of IAA as a signaling molecule over the more than 1 billion years that separate the green plant and the heterokont lineages. The study of a recently identified NAA-hypersensitive mutant in E. siliculosus will help develop the scenario further.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of Ectocarpus siliculosus

The experiments were carried out using a unialgal laboratory culture of haploid E. siliculosus parthenosporophyte isolate Ec 32 (Culture Collection of Algae and Protozoa accession no. 1310/4; origin, San Juan de Marcona, Peru), which was produced by germination of unfertilized gametes (Le Bail et al., 2008a). Thalli were grown in 100-mL petri dishes or 10-L containers in autoclaved ASW (450 mm NaCl, 10 mm KCl, 9 mm CaCl2, 30 mm MgCl2, and 16 mm MgSO4 at pH 7.8) enriched with Provasoli medium (ASWp; Starr and Zeikus, 1993) in a controlled-environment cabinet at 13°C with a 14:10-h light:dark cycle (light intensity of 29 μmol photons m−2 s−1).

Because some of the studied mutants display abnormal sporangia and no gametophytic state, controlled production of unfertilized gametes or spores was not possible. Therefore, young organisms (approximately 10 cells) were obtained by filtrating a mass culture containing individuals at different developmental stages.

For the ablation experiments, early filaments were cut with a needle into pieces containing either E cells only or R cells only. Corresponding fragments were grown in separate petri dishes in ASW. NAA (5 × 10−6 m) was added to half of the petri dishes of each cell type. Filament development was observed 1 week after ablation. The number of branches was counted, and statistical analyses were performed using Student's t test. n = 32 for ASW and n = 23 for ASW + NAA 5 × 10−6 m.

Application of Auxin Compounds on E. siliculosus Tissues

All the phytohormones were purchased from Duchefa Biochemie. NAA (N0903), IAA (I0901), IBA (I0902), 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (D0910), and dicamba (D0920) were dissolved in 1 n NaOH at an initial concentration of 0.5 m and then successively diluted in ASW to 5 mm, 500 μm, and 50 μm. 4-Chlorophenoxyacetic acid (C0909) and PAA (P0913) were dissolved in ethanol at the same concentrations. TIBA and NPA were dissolved in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide. All the auxin compounds, as well as the auxin transport inhibitors, were used at final concentrations of 50, 5, and 0.5 μm. Final solvent concentrations (e.g. 10−4, 10−5, and 10−6 n, respectively, for NaOH) were used as controls. Only concentrations having an effect on E. siliculosus development are discussed in the text.

For the microarray experiment, RNA was extracted from a sporophyte culture grown in natural seawater for several weeks. Cultures were then subdivided into equal amounts and transferred into petri dishes containing ASWp with shaking. After 48 h of acclimation, the medium was replaced by either fresh ASWp + NaOH 10−4 n (control) or ASWp + NAA 50 μm, grown with gentle shaking, and collected after 30 min or 3 h. For the expression kinetics, cultures were prepared as for the microarray experiments, but samples were collected after 30 min or 1, 6, 12, and 24 h.

Generation and Observation of Mutants

Mutants were produced following 20 min of UV-B irradiation of E. siliculosus EC 32 unfertilized gametes. Individuals displaying morphogenetic alterations were screened with a binocular microscope. The stability of the selected phenotype was checked for at least five parthenogenetic generations. Detailed fine-scale observations were performed on an Olympus IX 51 inverted microscope.

Auxin Detection and Quantification

Axenic algal material (50–200 mg) corresponding to mature organisms was mixed with 1 mL of 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7, containing 1 ng mL−1 [indole-13C6]IAA (internal standard), homogenized in Retsch mixer mill, and extracted for 1 h at 4°C. Samples were then centrifuged, and the resulting supernatants were transferred to clean tubes and acidified to pH 2.7 with 1 m hydrochloric acid. Solid-phase extraction was performed using 50-mg BondElut C18 columns (Varian). After application of the samples, columns were washed with 1 mL of 1% (v/v) formic acid and dried. Compounds of interest were eluted using 1 mL of acetonitrile containing 0.2% (v/v) formic acid.

Following the solid-phase extraction, samples were vacuum dried, dissolved in 1mL of methanol:acetone mixture (1:9), and reacted with 10 μL of 2 m trimethylsilyl-diazomethane in hexane for 1 h. The excess of derivatization reagent was quenched with 10 μL of 2 m acetic acid in n-heptane, and samples were dried in a stream of nitrogen.

For liquid chromatography, samples were reconstituted in 10 μL of 20% methanol. Chromatography was performed on a 10- × 1-mm Thermo BetaMax precolumn (Thermo Electron) connected to a 50- × 1-mm Waters Symmetry Shield C-18 analytical column (Waters). A linear gradient of 20% to 90% methanol containing 0.2% (v/v) formic acid over 20 min at 35 μL min−1 flow rate was employed to separate analytes of interest, followed by 5 min of washing with 100% methanol and a 5-min 20% methanol/0.2% formic acid equilibration period for each injection. The Waters Quattro Ultima mass spectrometer was operated in Multiple Reaction Monitoring mode with electrospray ion source block and desolvation temperatures kept at, correspondingly, 100°C and 290°C. Acquired data were processed using Waters MassLynx software.

For gas chromatography, samples were dissolved in 25 μL of acetonitrile and derivatized with 5 μL of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide/1% trimethylchlorosilane at 75°C for 30 min. Separation of the compounds of interest was achieved using an 80°C to 280°C linear temperature gradient on a 30-m × 0.25-mm Varian CP-Sil8 CB column, effluent of which was analyzed by the JEOL JMS-700 magnetic sector mass spectrometer operating in Multiple Reaction Monitoring mode. The electron-impact ion source and the inlet pipe were kept at 260°C, and an ionization energy of 70 eV was used. Data were processed using JEOL XMass software.

In order to release IAA from conjugated forms, samples were treated beforehand with 7 n NaOH for 24 h.

IAA Immunocytochemical Localization

The protocol was adapted from Avsian-Kretchmer et al. (2002) with different fixation methods. Sporophytes were grown on coverslips from germination to the required stage. They were prefixed in 2% (w/v) aqueous solution of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (Sigma-Aldrich) and postfixed in a fresh fixation buffer (47.5% ethanol, 5% acetic acid, and 10% formaldehyde) during 30 min at room temperature. The fixation buffer was changed. Tissues were then placed for 5 min in a phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS; 2.7 mm KCl, 6.1 mm Na2HPO4, and 3.5 mm KH2PO4, pH 7), incubated for 45 min in a blocking solution (0.1% [v/v] Tween 20, 1.5% [w/v] Gly, and 5% [w/v] bovine serum albumin [BSA]), and rinsed in a regular salt rinse solution (0.1% [v/v] Tween 20, 0.8% [w/v] BSA, and 0.88% [w/v] NaCl) for 5 min. They were briefly washed in PBS with 0.8% (w/v) BSA. One hundred microliters of 1:100 (w/v) monoclonal anti-IAA antibody (1 mg mL−1; A0855; Sigma) or monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (1 mg mL−1; T6199; Sigma) was placed on each coverslip and incubated overnight at 4°C. Three 10-min vigorous washes with high-salt rinse solution (2.9% [w/v] NaCl, 0.1% [v/v] Tween 20, and 0.1% [w/v] BSA) were followed by a 10-min wash with a regular salt rinse and a brief rinse with 0.8% (v/v) BSA and a rinse in PBS. One hundred microliters of a 1:100 (v/v) dilution of the 1 mg mL−1 anti-mouse IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (A4312; Sigma) was added to each slide and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. Five 10-min washes in a regular salt rinse solution were followed by a brief wash in PBS. Coverslips were placed in detection buffer (100 mm Tris, pH 9.5, 100 mm NaCl, and 50 mm MgCl2) during 5 min and then in detection buffer with 350 μL of nitroblue tetrazolium and 150 μL of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate for 50 mL of buffer. The reaction was stopped in 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, and 5 mm EDTA. Coverslips were then mounted on a slide in Gel-mount (Biomeda) for microscopic observations.

Microarray

Microarrays were composed of 1,152 PCR products, corresponding to sporophytic and gametophytic tissues, and are fully described by Peters et al. (2008). Targets were prepared from RNA extracted from 200 mg of ground sporophytic material and treated with NAA (see culture conditions), and RNA was extracted with an extraction buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1.5 m NaCl, 2% cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide, 50 mm EDTA, and 50 mm dithiothreitol) for 1 h with shaking and then with 1 volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1). Polysaccharides were precipitated in the aqueous phase with one-fourth volume of 100% ethanol and then extracted with 1 volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. RNAs were precipitated for 2 h with 2.4 m lithium chloride and 1% β-mercaptoethanol and then with a phenol-chloroform extraction and alcohol precipitation. Microarray hybridizations were performed as described by Peters et al. (2008). The data are available at the Array Express at EMBL-EBI with accession number E-MEXP-1716.

Transcript-Level Quantification by Real-Time PCR

Biological triplicates were prepared from each type of material. Oligonucleotides and RNAs were prepared as described by Peters et al. (2008). The list of oligonucleotides used is presented in Table III. In addition to DNase-I treatment, remnants of genomic DNA contaminant were quantified by amplification of an intron and subtracted from the other values. EsEF1α was chosen as a constitutively expressed gene based on the study by Le Bail et al. (2008b) and used for transcript-level normalization. The normalized data were expressed as means ± sd calculated from the three independent biological experiments.

Table III. Oligonucleotides used for the quantification of transcripts by real-time reverse transcription-PCR.

Oligonucleotides (Eurogentec, purification Selective Precipitation Optimized Process) were designed using the software Primer Express 1.0 (PE Applied Biosystems). Sequence is indicated from 5′ to 3′. NA, Not applicable.

Sequence Analyses

Sequences of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) proteins involved in the different auxin processes were retrieved from the UniProt database release 15.8 (UniProt Consortium, 2009). Their most similar relatives were searched for within the complete proteome of E. siliculosus (Ectocarpus Genome Consortium, unpublished data) using BLASTP version 2.2.18 (Altschul et al., 1997) with a cutoff E value set at 1 × 10−5. In order to check for a BBH, the best hit in E. siliculosus for a given Arabidopsis sequence was used as a query in a BLASTP search within the whole genome of Arabidopsis. A BBH was recorded when the best hit for this second search was the starting Arabidopsis protein. The expression of E. siliculosus proteins was assessed by the existence of a corresponding EST in the EST databank (Dittami et al., 2009). Functional domains were identified using the InterProScan software (Zdobnov and Apweiler, 2001).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Table S1. Sequence conservation between Arabidopsis and E. siliculosus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to C. Maisonneuve and L. Dartevelle for maintaining the E. siliculosus cultures.

References

- Abad MJ, Bedoya LM, Bermejo P. (2008) Natural marine anti-inflammatory products. Mini Rev Med Chem 8: 740–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbrust EV, Berges JA, Bowler C, Green BR, Martinez D, Putnam NH, Zhou S, Allen AE, Apt KE, Bechner M, et al. (2004) The genome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana: ecology, evolution, and metabolism. Science 306: 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avsian-Kretchmer O, Cheng J, Chen L, Moctezuma E, Sung ZR. (2002) Indole acetic acid distribution coincides with vascular differentiation pattern during Arabidopsis leaf ontogeny. Plant Physiol 130: 199–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf SL. (2008) An overview of the phylogeny and diversity of eukaryotes. J Syst Evol 46: 263–273 [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Sun H, Brian L, Quatrano RL, Muday GK. (2002) Early embryo development in Fucus distichus is auxin sensitive. Plant Physiol 130: 292–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F, Taylor A, Brownlee C. (1994) Cell fate determination by the cell wall in early Fucus Dev Sci 263: 1421–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierfreund NM, Reski R, Decker EL. (2003) Use of an inducible reporter gene system for the analysis of auxin distribution in the moss Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell Rep 21: 1143–1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billoud B, Le Bail A, Charrier B. (2008) A stochastic 1D nearest-neighbor automaton models early development of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus. Funct Plant Biol 35: 1014–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouget FY, Berger F, Brownlee C. (1998) Positional dependent control of cell fate in the Fucus embryo: role of intercellular communication. Development 125: 1999–2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Allen AE, Badger JH, Grimwood J, Jabbari K, Kuo A, Maheswari U, Martens C, Maumus F, Otillar RP, et al. (2008) The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 456: 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley PM. (1991) Plant hormones do have a role in controlling growth and development of algae. J Phycol 27: 317–321 [Google Scholar]

- Charrier B, Coelho SM, Le Bail A, Tonon T, Michel G, Potin P, Kloareg B, Boyen C, Peters AF, Cock JM. (2008) Development and physiology of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus: two centuries of research. New Phytol 177: 319–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke TJ, Poli D, Sztein AE, Cohen JD. (2002) Evolutionary patterns in auxin action. Plant Mol Biol 49: 319–338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cove D. (2000) The moss Physcomitrella patens. J Plant Growth Regul 19: 275–283 [Google Scholar]

- Cove D, Bezanilla M, Harries P, Quatrano R. (2006) Mosses as model systems for the study of metabolism and development. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 497–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Grigoriev I, Fischer R, Tominaga M, Robinson DG, Hasek J, Paciorek T, Petrásek J, Seifertová D, Tejos R, et al. (2008) Auxin transport inhibitors impair vesicle motility and actin cytoskeleton dynamics in diverse eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4489–4494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittami SM, Scornet D, Petit J, Segurens B, Da Silva C, Corre E, Dondrup M, Glatting K, Konig R, Sterck L, et al. (2009) Global expression analysis of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus (Phaeophyceae) reveals large-scale reprogramming of the transcriptome in response to abiotic stress. Genome Biol 10: R66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friml J. (2009) Subcellular trafficking of PIN auxin efflux carriers in auxin transport. Eur J Cell Biol 89: 231–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp AD, Kelly S, Ulber R, Lang S. (2009) Fucoidans and fucoidanases: focus on techniques for molecular structure elucidation and modification of marine polysaccharides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 82: 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai T, Nimura K, Yasui H, Mizuta H. (2006) Regulation of sorus formation by auxin in Laminariales sporophyte. J Appl Phycol 18: 95–101 [Google Scholar]

- Katsaros C, Karyophyllis D, Galatis B. (2006) Cytoskeleton and morphogenesis in brown algae. Ann Bot (Lond) 97: 679–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepinski S. (2007) The anatomy of auxin perception. Bioessays 29: 953–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieliszewski MJ, Lamport DT. (1994) Extensin: repetitive motifs, functional sites, post-translational codes, and phylogeny. Plant J 5: 157–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klarzynski O, Plesse B, Joubert JM, Yvin JC, Kopp M, Kloareg B, Fritig B. (2000) Linear beta-1,3 glucans are elicitors of defense responses in tobacco. Plant Physiol 124: 1027–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloareg B, Quatrano RS. (1988) Structure of the cell-walls of marine algae and ecophysiological functions of the matrix polysaccharides. Oceanogr Mar Biol 26: 259–315 [Google Scholar]

- Kropf DL. (1992) Establishment and expression of cellular polarity in fucoid zygotes. Microbiol Rev 56: 316–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf DL. (1997) Induction of polarity in fucoid zygotes. Plant Cell 9: 1011–1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf DL, Coffman HR, Kloareg B, Glenn P, Allen VW. (1993) Cell-wall and rhizoid polarity in Pelvetia embryo. Dev Biol 160: 303–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S, Jürgens G, De Smet I. (2008) The evolving complexity of the auxin pathway. Plant Cell 20: 1738–1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S, Shao N, Bock R, Jürgens G, De Smet I. (2009) Auxin signaling in algal lineages: fact or myth? Trends Plant Sci 14: 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bail A, Billoud B, Maisonneuve C, Peters AF, Mark Cock J, Charrier B. (2008a) Early development of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus (Ectocarpales, Phaeophyceae) sporophyte. J Phycol 44: 1269–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bail A, Dittami SM, de Franco P, Rousvoal S, Cock MJ, Tonon T, Charrier B. (2008b) Normalization genes for expression analyses in the brown alga model Ectocarpus siliculosus. BMC Mol Biol 9: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ljung K, Hull AK, Kowalczyk M, Marchant A, Celenza J, Cohen JD, Sandberg G. (2002) Biosynthesis, conjugation, catabolism and homeostasis of indole-3-acetic acid in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 49: 249–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller DG. (1967) Generationswechsel, Kernphasenwechsel und Sexualität der Braunalge Ectocarpus siliculosus im Kulturversuch. Planta 75: 39–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafisi M, Goregaoker S, Botanga CJ, Glawischnig E, Olsen CE, Halkier BA, Glazebrook J. (2007) Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 monooxygenase 71A13 catalyzes the conversion of indole-3-acetaldoxime in camalexin synthesis. Plant Cell 19: 2039–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Fonstein M, D'Souza M, Pusch GD, Maltsev N. (1999) The use of gene clusters to infer functional coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2896–2901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paciorek T, Zazímalová E, Ruthardt N, Petrásek J, Stierhof Y, Kleine-Vehn J, Morris DA, Emans N, Jürgens G, Geldner N, et al. (2005) Auxin inhibits endocytosis and promotes its own efflux from cells. Nature 435: 1251–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry G, Estelle M. (2006) Auxin receptors: a new role for F-box proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol 18: 152–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters AF, Marie D, Scornet D, Kloareg B, Cock JM. (2004) Proposal of Ectocarpus siliculosus (Ectocarpales, Phaeophyceae) as a model organism for brown algal genetics and genomics. J Phycol 40: 1079–1088 [Google Scholar]

- Peters AF, Scornet D, Ratin M, Charrier B, Monnier A, Merrien Y, Corre E, Coelho SM, Cock JM. (2008) Life-cycle-generation-specific developmental processes are modified in the immediate upright mutant of the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus. Development 135: 1503–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N, Burrowes R, Rousseau F, de Reviers B, Saunders GW. (2008) Resolving evolutionary relationships among the brown algae using chloroplast and nuclear genes. J Phycol 44: 394–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringli C, Keller B, Ryser U. (2001) Glycine-rich proteins as structural components of plant cell walls. Cell Mol Life Sci 58: 1430–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A, Goulitquer S, Salaün J, Tonon T, Correa JA, Potin P. (2008) Copper stress induces biosynthesis of octadecanoid and eicosanoid oxygenated derivatives in the brown algal kelp Laminaria digitata. New Phytol 180: 809–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr RC, Zeikus JA. (1993) Utex: the culture collection of algae at the University of Texas at Austin. J Phycol 29: 1–106 [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova AN, Robertson-Hoyt J, Yun J, Benavente LM, Xie D, Dolezal K, Schlereth A, Jürgens G, Alonso JM. (2008) TAA1-mediated auxin biosynthesis is essential for hormone crosstalk and plant development. Cell 133: 177–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern CD. (2006) Evolution of the mechanisms that establish the embryonic axes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16: 413–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, Hishiyama S, Jikumaru Y, Hanada A, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, Zhao Y, Kamiya Y, Kasahara H. (2009) Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoxime-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5430–5435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Basu S, Brady SR, Luciano RL, Muday GK. (2004) Interactions between auxin transport and the actin cytoskeleton in developmental polarity of Fucus distichus embryos in response to light and gravity. Plant Physiol 135: 266–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakhovskaya ER, Maslov YI, Shishova MF. (2007) Phytohormones in algae. Russ J Plant Physiol 54: 163–170 [Google Scholar]

- Titapiwatanakun B, Blakeslee JJ, Bandyopadhyay A, Yang H, Mravec J, Sauer M, Cheng Y, Adamec J, Nagashima A, Geisler M, et al. (2009) ABCB19/PGP19 stabilises PIN1 in membrane microdomains in Arabidopsis. Plant J 57: 27–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt Consortium (2009) The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Res 37: D169–D174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AW, Bartel B. (2005) Auxin: regulation, action, and interaction. Ann Bot (Lond) 95: 707–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Yamamoto KT. (1998) Differential effects of 1-naphthalene-acetic acid, indole-3-acetic acid and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid on the gravitropic response of roots in an auxin-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis, aux1. Plant Cell Physiol 39: 660–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HS, Hackett JD, Ciniglia C, Pinto G, Bhattacharya D. (2004) A molecular timeline for the origin of photosynthetic eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol 21: 809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R. (2001) InterProScan: an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17: 847–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.