Abstract

Background

Adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) have the potential to differentiate into osteogenic cells that can be seeded into scaffolds for tissue engineering for use in craniofacial bone defects. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) has been widely used as a lineage marker for mammalian cells. The use of fluorescent proteins enables cells to be tracked during manipulation such as osteogenic differentiation within three-dimensional scaffolds. The purpose of this study was to examine whether ASCs introduced with GFP-encoding lentivirus vector exhibit adequate GFP fluorescence and whether the expression of GFP interfered with osteogenic differentiation of ASCs in both monolayer and three-dimensional scaffolds in vitro.

Methods

Primary ASCs were harvested from the inguinal fat pad of Sprague Dawley rats. Isolated ASCs were cultured and infected with a lentiviral vector encoding GFP and plated into both mono-layers and three-dimensional scaffolds in vitro. The cells were then placed in osteogenic medium. Osteogenic differentiation of the GFP-ASCs was assessed using alizarin red S, alkaline phosphate staining, and immunohistochemistry staining of osteocalcin with quantification of alizarin red S and osteocalcin staining.

Results

The efficacy of infection of ASCs with a lentiviral vector encoding GFP was high. Cell-cultured GFP-ASCs remained fluorescent over the 8 weeks of the study period. The GFP-ASCs were successfully induced into osteogenic cells both in monolayers and three-dimensional scaffolds. Whereas the quanitification of alizarin red S revealed no difference between osteoinduced ASCs with or without GFP, the quantification of osteocalcin revealed increased staining in the GFP group.

Conclusions

Transduction of isolated ASCs using a lentiviral vector encoding GFP is an effective method for tracing osteoinduced ASCs in vitro. Quantification data showed no decrease in staining of the osteoinduced ASCs.

Keywords: Green fluorescent protein, adipose stem cells, Gelfoam, osteogenic differentiation

Supply of sufficient bone for reconstruction of the craniofacial skeleton is among the greatest clinical challenges for the craniofacial surgeon today.1 These deficits may occur after trauma, tumor resection, or during surgical correction of congenital anomalies.2 Human adipose tissue–derived stem cells (ASCs) can be induced into functional osteogenic cells that form bone when seeded onto scaffolds and thereby can be used to repair bone defects.3–6 Compared with bone marrow stem cells, ASCs are more abundant, are easier to obtain, and involve lower donor-site morbidity. Thus, it is believed that ASCs represent an ideal substitute for bone marrow stem cells for use in cell-based tissue engineering strategies.7 However, the limited ability to track the progeny and the products of ASCs in vivo greatly hinders further studies.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) exhibits fluorescence in living cells, which allows in situ detection in the living animal.8,9 The fluorescent signal emitted from GFP can be detected with optical imaging, fluorescence microscopy, or flow cytometry.10 This property of GFP has been widely used for in vitro investigations with living cells and has been experimentally tested in vivo to track the distribution of transplanted cells in the brain, the liver, the muscle, and the retina.11–14

Adenoviral vectors have been used to successfully introduce GFP into ASCs because they are able to infect dividing and non-dividing cells.15,16 However, the application of adenoviral vectors is limited by the lack of persistent target gene delivery and the immune response in immunocompetent animals and humans.17 Lentiviral vectors, based on human immunodeficiency virus, have been used for gene therapy.18 Lentiviral vectors can transduce non-dividing cells and incorporate their genome into the host genome, allowing for long-term or permanent gene expression. In addition, lentiviral vectors do not seem to elicit a robust immune response and are less prone to transcriptional silencing than oncoretroviral vectors.19 These properties make lentiviral vectors ideal for gene therapy in stem cells.20–22

The aims of this study were to test whether ASCs exhibit GFP fluorescence after transfection with GFP-encoding lentiviral vector and to show the ability of GFP-ASCs to maintain osteogenic differentiation after lentiviral transfection.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Culture of ASC

All experiments followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing approximately 400 g each were killed. The fat pad was harvested from the inguinal area and minced by scissors. The minced tissues were digested in a 0.12% collagenase solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking for 1 hour. Next, an equal volume of normal medium, consisting of Dulbecco Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco Invitrogen Corp, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco Invitrogen Corp) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco Invitrogen Corp), was added. The tissue was centrifuged and the pellet was resuspended in normal medium and then filtered using a 100-μm cell strainer. The cells were plated in a 100-cm2 culture dish. The normal medium was changed at 24 and 48 hours, and when the cells reached confluence, they were trypsinized and placed in a 6-well plate at 104 cells per well in 10% FBS for lentiviral transduction. Additional ASCs were placed in a separate 6-well plate at 105 cells per well for verification of osteogenic and adipogenic differentiations.

Preparation of Lentiviral Vector

To obtain lentiviral particles, HEK-293T cells were plated at 7 to 8 × 105 cells per T-175 tissue culture flask in the growth medium (10% high-glucose DMEM) without antibiotics, 24 hours before transfection. Forty micrograms of plasmid DNA was used for the transfection, which consisted of 20 μg of the transfer vector plasmid pCS-CDF-CG-PRE, 12 μg of the packaging plasmid pMDLg/pRRE, 3 μg of the Rev plasmid pRSV-Rev, and 5 μg of the envelope plasmid pMD.G (RIKEN, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan).

To achieve precipitation, the plasmids were diluted with 100-μL Opti-MEM and 120-μL Lipofectamine 2000 to a final volume of 220 μL and incubated together at room temperature for 20 minutes. The DNA/Lipofectamine 2000 complex was added dropwise to the culture flask and incubated at 37°C in a carbon dioxide incubator overnight. After 12 hours, the medium was replaced with 25 mL of 10% high-glucose DMEM. This conditioned medium was collected after an additional 48 hours of incubation and filtered through 0.45-μm cellulose acetate filters. The conditioned medium was then ultracentrifuged at 4°C at 20,000 rpm for 2 hours, and the virus pellet was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline and frozen at −80°C. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was determined by the infection of HEK-293T cells with serial dilutions of the vector stocks.

Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Transduction and Examination of GFP Fluorescence

Infection of cells with the GFP lentivirus was performed in serum-free DMEM medium for 12 hours at 37°C at several selected MOIs. After infection, the lentivirus-containing medium was replaced with the control medium supplemented with 10% FBS. After 48 hours, GFP-positive cells were scored using fluorescence microscopy where the densities of the different colors were measured for quantification. The infection efficiency was determined by counting positive and negative cells in 5 representative high-power fields.

Osteogenic Differentiation of ASCs

Both ASCs and GFP-ASCs were trypsinized and reseeded at a cell density of 105 cells per well onto 6-well plates. After full adherence to the growth surface, half of the wells were placed in an osteogenic differentiation medium, containing 50-μmol/L ascorbate-2-phosphate, 10-mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, and 0.01-μmol/L 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. The remaining cells were placed in a normal medium as controls. All the cells were cultured in these conditions for 4 weeks.

Verification of Osteogenic Differentiation

Alizarin Red S Staining of Calcified Structures

Alizarin red (AR) S staining and elution were used to quantify calcium levels. Cells were fixed in 95% ethanol for 10 minutes. They were washed with sterile water and incubated with 0.1% AR S Tris-HCL solution at 37°C for 30 minutes. Ten visual fields were then randomly selected from both the GFP-positive and the GFP-negative slides for data analysis. The data were evaluated using the mean intensity and expressed as the mean number of nodules per4× field.23,24

Alkaline Phosphatase Staining

Cells were fixed in acetone for 30 seconds and then stained with a naphthol Fast blue staining solution (kit 85L2-1KT; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes. They were counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin solution for 3 minutes.

Immunohistochemistry for Osteocalcin

Goat anti–rat osteocalcin primary antibody (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA) was diluted to a concentration of 5 μg/mL. The antigen was unmasked via heat treatment with 10-mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for approximately 20 minutes. Visualization of osteocalcin was achieved by exposing the primary antibody to biotinylated immunoglobulin G and chromogen from the avidin-horseradish peroxidase kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).25 As in the AR S groups, 10 visual fields were then randomly selected from both the GFP-positive and the GFP-negative slides for data analysis. The data were evaluated using the mean intensity and expressed as the mean number of nodules per 4 × field.23,24

Implantation of GFP-ASCs Into Three-Dimensional Gelfoam Scaffold

Sterile gelatin sponge sheets (Gelfoam; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Inc, Kalamazoo, MI) were used as three-dimensional scaffolds. The Gelfoam was trimmed into an 8-mm diameter disk and placed into 48-well plates. The GFP-ASCs in suspension were seeded onto each Gelfoam scaffold at a cell density of 3 × 106 cell/mL (200 μL per disk) for cell distribution and proliferation analyses. The GFP-ASC–impregnated Gelfoam sponges were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours and then placed in normal medium. The cell-impregnated Gelfoam sponges remained in normal medium for 5 days and were then transferred to an osteogenic medium. After 3 weeks of osteogenic induction, the constructs were observed under fluorescence microscopy and subjected to AR, alkaline phosphatase (AP), and immunohistochemistry staining for osteocalcin. The control constructs were incubated in normal medium for the duration of the experiment.

Results

Green Fluorescent Protein Fluorescence in ASCs

With an MOI of 40:1, more than 90% of ASCs were positive for GFP. No cell toxicity was observed by fluorescence microscopy 24 hours after transduction (Figs. 1A, B). The GFP fluorescence reached peak levels after 48 hours and declined gradually. Eight weeks after transduction, the GFP fluorescence per cell was lower, although still readily detectible (Figs. 1C, D).

FIGURE 1.

Green fluorescent protein fluorescence in GFP-ASCs 48 hours and 8 weeks after lentivirus infection. Light photomicrograph (A) and fluorescence photomicrograph (B) of GFP-ASCs cultured for 48 hours after infection with lentiviral vector. More than 90% of the ASCs were positive for GFP expression. Light photomicrograph (C) and fluorescence photomicrograph (D) of ASCs cultured for 8 weeks after infection with lentiviral vector. The GFP fluorescence is still easily detected. (Original magnification × 100.)

Osteogenic Differentiation of GFP-ASCs

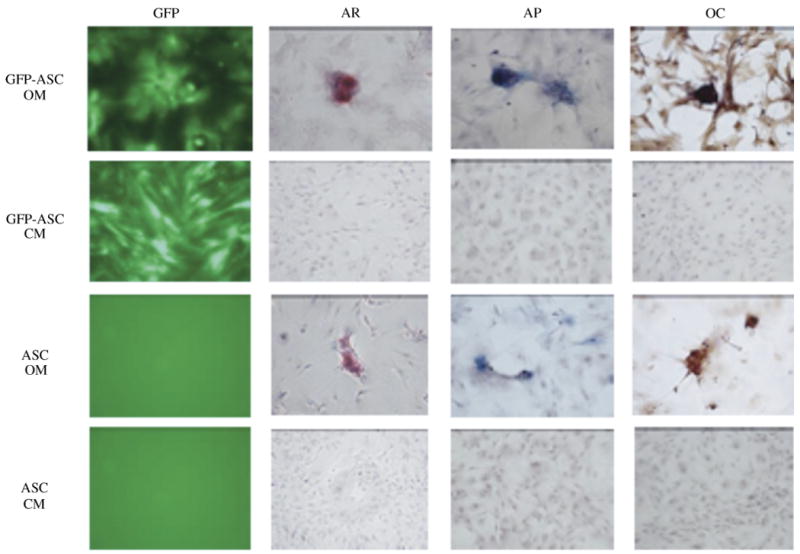

The GFP-ASCs were transferred to either the osteogenic medium or the control medium. In the osteogenic medium, the appearance of the GFP-ASCs changed from an elongated fibroblastic shape to a round, polygonal configuration. These cells aggregated to form islands of differentiated cells separated by secreted matrix. Four weeks after osteogenic induction, larger mineralized nodules were formed that had a high fluorescent intensity, indicating occupation by GFP-ASCs (Fig. 2). The mineralized nodular structures stained intensely red with AR S. The AP staining demonstrated significant activity in osteoinduced GFP-ASCs, especially around mineralized nodules. Immunohistochemistry staining for osteocalcin was positive in GFP-ASCs cultured in the osteogenic medium, and all stains were negative in the control medium (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 2.

A, GFP-ASCs were incubated in the control medium for 3 weeks and showed an elongated fibroblastic appearance. B, Fluorescence microscopic images. C, After culture under osteogenic differentiation conditions for 3 weeks, the GFP-ASCs aggregated together in islands. D, Fluorescence microscopic images. (Original magnification × 100.)

FIGURE 3.

Confirmation of the presence of ASCs by GFP fluorescence (GFP) and osteogenic differentiation of GFP-ASCs, AR staining, AP, and immunohistochemistry for osteocalcin (OC). Cells were cultured either in the control medium (CM) or the osteogenic medium (OM) for 4 weeks. (Original magnification × 200.)

Osteogenic Differentiation of GFP-ASCs Inside a Three-Dimensional Gelfoam Scaffold

Twenty-four hours after seeding into a three-dimensional Gelfoam scaffold, the GFP-ASCs were observed under fluorescence microscopy. The GFP-ASCs were evenly distributed throughout the construct. More extensive accumulation of GFP-ASCs was seen after 2 weeks of differentiation (Fig. 4). The integrity of the Gelfoam matrix became unstable at the 4-week time interval, which did not allow for accurate assessment of the cells beyond that time.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of ASC-GFP in the three-dimensional Gelfoam scaffold 48 hours and 2 weeks after the viral infection and under fluorescence microscopy. A and B, Forty-eight hours after the inoculation of the cells. C and D, Two weeks after osteoinduction, increased GFP-positive cells were observed. (Original magnification × 100.)

Similar to cell culture, the immunohistochemistry for osteo-calcin revealed extensive positive staining in the constructs of GFP-ASCs seeded in Gelfoam 3 weeks after osteogenic differentiation (Fig. 5), whereas no osteocalcin was seen in the control groups. The AR and AP stainings were inconclusive secondary to nonspecific staining of the Gelfoam constructs.

FIGURE 5.

Immunohistochemical staining for osteocalcin in the GFP-ASCs inside the Gelfoam scaffold. A, The GFP-ASC scaffold construct cultured in normal medium. B, The GFP-ASC scaffold construct cultured in osteogenic medium. (Original magnification of all images × 200.)

Quantitative Analysis of Bone Formation in ASCs and GFP-ASCs

Quantitative analysis of calcium nodules using AR revealed no significant difference between the ASCs and the GFP-ASCs os-teoinduced for 4 weeks (43 ± 14 vs 43.6 ± 11.5, respectively; P = 0.91; Fig. 6). However, the expression of osteocalcin was found to be significantly higher in the osteoinduced GFP-positive cells than the osteoinduced GFP-negative cells after 4 weeks (0.12 ± 0.03 vs 0.07 ± 0.015, respectively; P = 0.001; Fig. 7).

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of AR S–stained calcium nodules in GFP-negative and GFP-positive ASCs in cell culture 4 weeks after osteoinduction in two-dimensional culture.

FIGURE 7.

Comparison of the osteocalcin expression of the GFP-negative and the GFP-positive ASCs in cell culture 4 weeks after osteoinduction in two-dimensional culture. There is a significant difference between the 2 groups (*P < 0.05).

Discussion

Establishing an effective identification technique to trace the products and the migration of transplanted cells in tissue engineering is critical. The incorporation of GFP into the ASC genome provides proof of the presence and the products of transplanted cells.26 Fluorescent dyes such as DiI, Hoechst 33342, and PKH26 have been used to trace cell origin and activity by marking the cell cytoplasm or nuclei with fluorescent markers. However, as the cells divide and multiply, the intensity of the original fluorescence fades.26–29 In addition, these fluorescent tracers may transfer to host cells in vivo, which is not desirable for long-term studies.27,28 Therefore, use of the GFP gene to identify the origin of the seeding cell in tissue engineering is superior to other cell fluorescent markers because the GFP will integrate into the cellular genome of the target cells.28

Studies involving nonviral vectors30 and replication-deficient recombinant adenoviruses15,16,31 have demonstrated efficient GFP gene transfer to ASCs. Although nonviral vectors can be produced in relatively large amounts and are likely to present fewer toxic or immunologic difficulties, they suffer from inefficient gene transfer. Furthermore, the expression of the introduced gene is transient.30,32 Adenoviruses can introduce genetic material into both dividing and nondividing cells, but all adenoviral vectors express the gene in adult animals for only a short time (between 5 and 20 days after infection) because of the immune response.17,33 Lentiviruses, such as the human immunodeficiency virus, are part of the retrovirus family. Unlike retroviruses, lentiviruses rely on active transport of the pre-integration complex through the nucleopore by the nuclear import machinery of the target cell.34 This strategy for nuclear targeting allows the lentivirus to infect both the dividing and the nondividing cells.35 In addition, lentiviral vectors do not seem to induce robust immune responses, allowing for stable, long-term transgene expression without detectable pathologic consequences ascribed to the vector.36 These properties of lentiviral vectors make them ideal for gene therapy, especially in stem cells.20–22

The continued ability to differentiate the stem cells after transfection is extremely important. When the GFP-ASCs were cultured in the osteogenic medium for 3 weeks, mineralized nodules with apparent mesenchymal condensation and osteoid matrix were observed.15,37–39 In addition, the mineralized nodules displayed high GFP fluorescence under fluorescence microscopy. These data support the conclusion that genetic manipulation with the lentiviral vector did not affect osteogenic differentiation of ASCs, and the osteogenic differentiation of ASCs did not seem to interfere with GFP expression. In addition, the products of the GFP-ASCs exhibit fluorescence that will allow easy differentiation between native and experimental cell products.

Gelfoam possesses high biocompatibility and has been used as a scaffold for cell seeding in bone tissue engineering studies.39 The pore size of 200 to 400 μm seen in Gelfoam benefits cell migration and allows angiogenesis formation.40 The integrity of the Gelfoam matrix became unstable at the 4-week time interval, which did not allow for accurate assessment of the cells beyond that time. This is a reflection of the Gelfoam stability rather than the stability of the cells. To observe the process of ASC proliferation, migration, and differentiation in scaffolds in vitro after gene transfer, we implanted GFP-ASCs into Gelfoam and successfully differentiated them in the osteogenic medium. The GFP-ASCs became evenly distributed within the constructs 24 hours after inoculation. Unfortunately, the presence of nonspecific staining in both AR and AP assays on the Gelfoam made it impossible to confirm the osteogenic differentiation of cells inside Gelfoam. However, immu-nohistochemistry for osteocalcin revealed positive staining in the constructs of GFP-ASCs 3 weeks after osteogenic differentiation. Extensive accumulation of GFP-ASCs inside the Gelfoam scaffold was also found, which demonstrates that the transduced ASCs maintained their proliferation, migration, differentiation, and GFP fluorescence ability in three-dimensional Gelfoam scaffolds at 3 weeks, before the dissolution of the Gelfoam scaffold.

Although our main goal was to have a qualitative assay for tracing the experimental ASCs using GFP, we were able measure the density of matrix deposition using AR and the expression of osteocalcin on differentiated GFP-ACSs. We saw no difference in bone matrix formation between the ASCs and the GFP-ACSs, whereas osteocalcin expression was increased. This confirms that our cells' functional capacity to produce bone nodules remained unchanged, if not enhanced, after GFP transfection while maintaining GFP expression. One advantage of lentiviral transduction is the incorporation of a stable genome into nondividing and dividing cells. Although it is not certain why the expression of osteocalcin increased 2-fold in the GFP group, the incorporation of the lentivirus in the cellular genome has been known to activate promoter genes and silence others.41 The art of virus-based gene delivery systems is still in evolution, and the consequences of transfection with lentiviral particles have not been fully elucidated. The increased efficiency of expression of osteocalcin in our model is unexpected and warrants further study. Our main experimental goal was to confirm that the cells we see in our scaffold were in fact the experimental ASCs using qualitative analysis of the data. When this model is applied in vivo, we will be able to verify that the experimental cells placed within the model are those growing and differentiating, as opposed to native cell migration and differentiation.

However, we do not propose that the actual experimental group will have lentivirus transduction. Furthermore, if osteoinduced ASCs were introduced in a clinical translational setting (humans), it would not be necessary or safe to use lentiviral-transduced cells. Green fluorescent protein usage would only apply in animal experimental settings to track where ASCs eventually resides. For these experimental purposes, we propose that the GFP group be run as a separate group from the main experimental group, looking at osteo-induction of ASCs. Thus, this is really a qualitative and confirmatory test rather than a quantitative test. By running a separate group in the experiment with GFP, it would eliminate any possible effects of GFP on the experimental groups. As long as the cells show expression of the green protein, we have strong evidence that, in fact, our cells have made it into our scaffold. In future studies, we plan to address the temporal expression of GFP in GFP-ASCs and compare the osteodifferentiation in GFP-ASCs and non–GFP-ASCs in three-dimensional cultures in future studies.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that ASCs can be transduced by lentiviral vectors with high efficiency, and can chronically express GFP. The GFP-ASCs maintained their ability to undergo osteogenic differentiation both in monolayers and three-dimensional scaffolds in vitro. Green fluorescent protein provides a direct and simple method to detect transplanted ASCs and does not impede osteogenic differentiation in vitro. This technique also represents a new option for efficient introduction of various therapeutic genes into ASCs such as BMP2, whose proteins have been demonstrated to play a critical role in bone healing by stimulating the differentiation of stem cells to an osteogenic lineage.18,41–43 However, extensive long-term in vivo studies using transduced ASCs are required to assess the safety and the efficacy of this technique.

References

- 1.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudas JR, Marra KG, Cooper GM, et al. The osteogenic potential of adipose-derived stem cells for the repair of rabbit calvarial defects. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:543. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000210629.17727.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokai LE, Rubin JP, Marra KG. The potential of adipose-derived adult stem cells as a source of neuronal progenitor cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1453. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000182570.62814.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Kemp DM. Human adipose-derived stem cells display myogenic potential and perturbed function in hypoxic conditions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:882. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:211. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hui JH, Li L, Teo YH, et al. Comparative study of the ability of mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, periosteum, and adipose tissue in treatment of partial growth arrest in rabbit. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:904. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalfie M. Green fluorescent protein. Photochem Photobiol. 1995;62:651. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1995.tb08712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, et al. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kandel ES, Chang BD, Schott B, et al. Applications of green fluorescent protein as a marker of retroviral vectors. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1997;23:325. doi: 10.1007/BF02674280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blomer U, Naldini L, Kafri T, et al. Highly efficient and sustained gene transfer in adult neurons with a lentivirus vector. J Virol. 1997;71:6641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6641-6649.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kafri T, Blomer U, Peterson DA, et al. Sustained expression of genes delivered directly into liver and muscle by lentiviral vectors. Nat Genet. 1997;17:314. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyoshi H, Takahashi M, Gage FH, et al. Stable and efficient gene transfer into the retina using an HIV-based lentiviral vector. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naldini L, Blomer U, Gallay P, et al. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin Y, Liu L, Li Z, et al. Pluripotency potential of human adipose–derived stem cells marked with exogenous green fluorescent protein. Mol Cell Biochem. 2006;291:1. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9188-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y, Tian W, Chen X, et al. Expression of exogenous or endogenous green fluorescent protein in adipose tissue–derived stromal cells during chondrogenic differentiation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;277:181. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-5996-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai Y, Schwarz EM, Gu D, et al. Cellular and humoral immune responses to adenoviral vectors containing factor IX gene: tolerization of factor IX and vector antigens allows for long-term expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:1401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieberman JR, Le LQ, Wu L, et al. Regional gene therapy with a BMP-2–producing murine stromal cell line induces heterotopic and orthotopic bone formation in rodents. J Orthop Res. 1998;16:330. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeifer A, Ikawa M, Dayn Y, et al. Transgenesis by lentiviral vectors: lack of gene silencing in mammalian embryonic stem cells and preimplantation embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251682798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Damme A, Thorrez L, Ma L, et al. Efficient lentiviral transduction and improved engraftment of human bone marrow mesenchymal cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:896. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2003-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gropp M, Reubinoff B. Lentiviral vector–mediated gene delivery into human embryonic stem cells. Methods Enzymol. 2006;420:64. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)20005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu FZ, Fujino M, Kitazawa Y, et al. Characterization and gene transfer in mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical-cord blood. J Lab Clin Med. 2005;146:271. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang Z, Sargeant TD, Hulvat JF, et al. Bioactive nanofibers instruct cells to proliferate and differentiate during enamel regeneration. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1995. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornell LE, Holmbom B, Eriksson A, et al. Enzyme and immunohistochemical assessment of myocardial damage after ischaemia and reperfusion in a closed-chest pig model. Histochemistry. 1992;98:341. doi: 10.1007/BF00271069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JA, Parrett BM, Conejero JA, et al. Biological alchemy: engineering bone and fat from fat-derived stem cells. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:610. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000069069.23266.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rieck B, Schlaak S. In vivo tracking of rat preadipocytes after autologous transplantation. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51:294. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000063758.16488.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohorko N, Kregar-Velikonja N, Repovs G, et al. An in vitro study of Hoechst 33342 redistribution and its effects on cell viability. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2005;24:573. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht570oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coyne TM, Marcus AJ, Woodbury D, et al. Marrow stromal cells transplanted to the adult brain are rejected by an inflammatory response and transfer donor labels to host neurons and glia. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2483. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biamonti G, Della Valle G, Talarico D, et al. Fate of exogenous recombinant plasmids introduced into mouse and human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:5545. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.15.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolbank S, Peterbauer A, Wassermann E, et al. Labeling of human adipose–derived stem cells for non-invasive in vivo cell tracking. Cell Tissue Bank. 2007;8:163. doi: 10.1007/s10561-006-9027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin XB, Lou SQ, Zhang K. Suitable vehicle for gene transfection into human adipose derived adult stem cells: pEGFPN1, Ad5-EGFP and rAAV-2/1-EGFP. J Clin Rehab Tissue Eng Res. 2007;11:1205. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li S, Huang L. Nonviral gene therapy: promises and challenges. Gene Ther. 2000;7:31. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somia N, Verma IM. Gene therapy: trials and tribulations. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:91. doi: 10.1038/35038533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bukrinsky MI, Haffar OK. HIV-1 nuclear import: in search of a leader. Front Biosci. 1999;4:D772. doi: 10.2741/bukrinsky. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bukrinsky MI, Haggerty S, Dempsey MP, et al. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature. 1993;365:666. doi: 10.1038/365666a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kay MA, Glorioso JC, Naldini L. Viral vectors for gene therapy: the art of turning infectious agents into vehicles of therapeutics. Nat Med. 2001;7:33. doi: 10.1038/83324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartmann C. A Wnt canon orchestrating osteoblastogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:151. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregory CA, Gunn WG, Peister A, et al. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Anal Biochem. 2004;329:77. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein GS, Lian JB. Molecular mechanisms mediating proliferation/differentiation interrelationships during progressive development of the osteoblast phenotype. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:424. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-4-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Partridge K, Oreffo O. Gene delivery in bone tissue engineering: progress and prospects using viral and nonviral strategies. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:295. doi: 10.1089/107632704322791934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueda H, Hong L, Yamamoto M, et al. Use of collagen sponge incorporating transforming growth factor-beta1 to promote bone repair in skull defects in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1003. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00211-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong L, Peptan I, Clark P, et al. Ex vivo adipose tissue engineering by human marrow stromal cell seeded gelatin sponge. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:511. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-2510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeuchi M, Dohi Y, Horiuchi K, et al. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 promotes osteogenesis within atelopeptide type I collagen solution by combination with rat cultured marrow cells. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:61. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]