Abstract

This research provides an example of testing for differential item functioning (DIF) using multiple indicator multiple cause (MIMIC) structural equation models. True/False items on five scales of the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP) were tested for uniform DIF in a sample of Air Force recruits with groups defined by gender and ethnicity. Uniform DIF exists when an item is more easily endorsed for one group than the other, controlling for group mean differences on the variable under study. Results revealed significant DIF for many SNAP items and some effects were quite large. Differentially-functioning items can produce measurement bias and should be either deleted or modeled as if separate items were administered to different groups. Future research should aim to determine whether the DIF observed here holds for other samples.

Keywords: Differential item functioning, Measurement invariance, SNAP, Personality

Differential item functioning (DIF) occurs when an item on a test or questionnaire has different measurement properties for one group of people versus another, irrespective of group-mean differences on the variable under study. For example, if the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP; Clark 1996) item: “I enjoy work more than play” has gender DIF, the probability of responding “True” is different for men versus women even when they are matched on degree of workaholism. Men and women may have different mean levels of workaholism—this is separate from the issue of DIF. Detecting DIF is important because it can lead to inaccurate conclusions about group differences and invalidate procedures for making decisions about individuals.

Numerous methods have been proposed for identifying DIF (Camilli and Shepard 1994; Holland and Wainer 1993; Millsap and Everson 1993). For most methods, it is desirable to select a few DIF-free items to define the matching criterion that is used for testing the other items for DIF. For some methods, people are matched on summed scores (i.e., the sum of observed item scores); for others, people are matched on an estimate of the latent variable that underlies the item scores. The matching is likely to be more accurate with latent-variable methods because they account for measurement error in the items.

DIF testing using latent variables may be accomplished using a multiple-group model or a single-group model with covariates. For categorical item data, both of these models may be parameterized either as an item response model fitted to the data directly or as a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model fitted to a matrix of polychoric correlations. Multiple group models are usually parameterized as item response models (this method is often referred to as IRT-LR-DIF; Thissen et al. 1986; Thissen et al. 1988, 1993), and single-group models with covariates are a type of multiple indicator multiple cause (MIMIC) structural equation model. Woods (in press) contrasts these two latent-variable approaches and compares them in simulations.

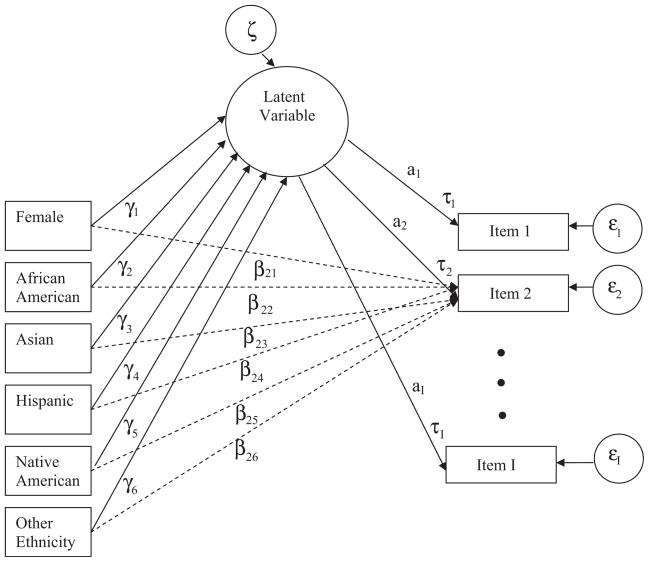

The present research is an application of the MIMIC-model approach, illustrated in Fig. 1 (this figure is further discussed below). Muthén (e.g., 1985,1988, 1989) popularized the use of MIMIC models to test for DIF using estimation methods appropriate for categorical data (see also MacIntosh and Hashim 2003; Muthén et al. 1991). A simple MIMIC model has one latent variable (i.e., factor) regressed on an observed grouping variable to permit group mean differences on the factor. An item is tested for DIF by regressing it (i.e., responses to it) on the grouping variable. There is evidence of differential functioning if group membership significantly predicts item responses, controlling for group mean differences on the factor.

Fig. 1.

Example MIMIC model permitting DIF for only item 2. γk = regression coefficient showing the group mean difference on the factor for covariate k; βjk = regression coefficient showing the group difference in the item threshold for item j and covariate k; aj = discrimination parameter; τj = threshold parameter (note that if an item exhibits DIF, τj depends on group); εj = measurement error for item j, ζ= residual for the factor

The MIMIC approach has several advantages (some of which are shared by IRT-LR-DIF). Matching is based on the latent variable which is likely to be more accurate than a summed score. Multidimensional items, or multiple factors, are easily modeled. Good software is available for estimating the models with methods designed for categorical data (e.g., Mplus; Muthén and Muthén 2007). It is easy to examine DIF for more than two groups at once and to control for additional covariates when testing for DIF. Covariates may be continuous or categorical. Separate item parameter estimates for each group are not a direct byproduct of the analysis (as with IRT-LR-DIF), but they are easily calculated as a function of the regression coefficients.

A disadvantage of MIMIC models is that they test for uniform, but not nonuniform1, DIF (see definitions in Mellenbergh 1989 and Camilli and Shepard 1994, p. 59). In the present study, the MIMIC approach was used despite this disadvantage because an important grouping variable in the data, ethnicity, has six levels, and the sample sizes are small in some groups (e.g., Ns=17, 68, 75). Muthén (1989) pointed out that MIMIC models perform well with smaller within-group sample sizes than multiple-group models, and more easily accommodate more than two groups. Based on simulations with binary item data, Woods (in press) concluded that DIF tests were more accurate with MIMIC models than IRT-LR-DIF when the focal-group N was small (e.g., around 25, 50, or 100).

The present study further investigates the five SNAP scales that showed differential test functioning (DTF) in previous research by testing individual items for DIF. Woods et al. (2008) found that five subscales of the SNAP functioned differently for Air Force recruits depending on their gender, ethnicity, or both. All items were considered simultaneously in this previous study so this was DTF rather than DIF. MIMIC-modeling is preferable to IRT-LR-DIF for these data because some of the focal-group sample sizes are small.

Method

Participants

The data are the same as those analyzed by Woods et al. (2008). The sample consisted of 2,026 Air Force recruits (1,265 male, 761 female) completing basic military training at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. Most were between 18 and 25 years old (Mdn=19). They self identified as Caucasian (1,305), African-American (348), Hispanic (75), Asian (68), or Native American (17), with the remaining 213 classified as “other.” Oltmanns and Turkheimer (2006) describe details about the sample and data collection procedures.

SNAP

The SNAP is a factor-analytically-derived self-report questionnaire that was originally developed as a tool for the assessment of personality disorders in terms of trait dimensions (Clark 1996). The 375 True/False items can be organized into three basic temperament scales (Negative Temperament, Positive Temperament, and Disinhibition) and 12 trait scales (Mistrust, Manipulativeness, Aggression, Self-harm, Eccentric Perceptions, Dependency, Exhibitionism, Entitlement, Detachment, Impulsivity, Propriety, and Workaholism). Alternatively, the items may be clustered into 13 diagnostic scales, corresponding to personality disorder categories presented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association 1987). Six validity scales identify individuals who have produced scores indicating response biases, careless/defensive responding, or deviance (Clark 1996; Simms and Clark 2006). Although it would be interesting and potentially valuable to evaluate DIF for all SNAP scales, the present investigation is limited to a subset of the scales that showed DTF in previous research: Three trait scales (Entitlement, Exhibitionism, and Workaholism), and two temperament scales (Disinhibition and Negative Temperament).

MIMIC Models

All MIMIC models used here were similar to the example shown in Fig. 1 (particular models are described in the next section). This is a standard one-factor2 CFA model plus observed covariates: The factor is regressed on dummy-coded indicators of gender (male = 0, female = 1) and ethnicity. The latent scale is identified by fixing the residual variance of the factor, ζ, to 1. There are five binary indicators of ethnicity, with white as the reference group. Because there were only 17 Native Americans, this category was used only for SNAP scales with fewer than 17 items (Entitlement and Exhibitionism). For the other scales (Disinhibition, Workaholism, and Negative Temperament), Native Americans were combined with the “other” ethnic group. Testing items for DIF involves regressing them on all of the grouping variables. The model in Fig. 1 permits DIF for item 2 while assuming all other items are DIF free.

All analyses were carried out using Mplus (version 4.21, Muthén and Muthén 2007). All models were parameterized as two-parameter logistic item response models and fitted to the data using the robust maximum likelihood estimator “MLR”. The Mplus parameterization is:

| (1) |

where uij is a response given by person i to item j, θ is the latent variable (i.e., factor), and aj and τj are discrimination and threshold parameters, respectively. The Mplus threshold differs from the threshold in Birnbaum’s (1968) popular 2PL model, bj. The 2PL parameterization is:

| (2) |

Nevertheless, τj is just a rescaled version of bj (τj = ajbj), so the interpretation is the same. The threshold is the value of θ at which the probability of endorsing the item is .5.

Data Analysis

The following procedures were repeated for each of the five SNAP scales. First, DIF-free items were identified empirically; the remaining items are studied items. Second, each studied item was individually tested for DIF. Third, a final model was constructed which permitted group variance in τj for all differentially-functioning (D-F) items. Estimates of discrimination parameters (aj), thresholds (τj), group mean differences on the factor for the kth covariate (γk), and DIF effects (i.e., regression coefficients indicating association with the grouping variables: βjks) from the final model are reported.

Identification of DIF-Free Items

If the DIF status of all items is unknown prior to a MIMIC analysis, it seems desirable to fit a model supposing all items have DIF: All items would be regressed on the grouping variables. Unfortunately, such a model is not identified. There is also a conceptual problem because at least one DIF-free item is needed to define the factor on which the groups are matched. Therefore, preliminary analyses were performed to select a subset of DIF-free items to define the factor in subsequent analyses. Every item was tested for DIF with all other items presumed DIF-free. This was accomplished by regressing one item at a time on all of the grouping variables. The model in Fig. 1 illustrates this type of test for item 2. Item j was assigned to the DIF-free subset if aj was at least .5 and all βjks were nonsignificant (α=.05).

The assumption that all other items are DIF-free is increasingly incorrect for scales with more DIF. However, previous simulation studies indicate that the error produced by violation of this assumption is inflated Type I error (Finch 2005; Stark et al. 2006; Wang 2004; Wang and Yeh 2003). In the present context, inflated Type I error means some DIF-free items will appear to have DIF and not be selected for the DIF-free subset. That is not particularly problematic. All items not included in the DIF-free subset are subsequently tested for DIF, so if an item really is DIF-free but excluded from the DIF-free subset initially, researchers are still likely to conclude it is DIF-free based on the subsequent test (which should be nonsignificant).

Testing each Item for DIF

Items not assigned to the DIF-free subset (studied items) were tested individually for DIF using likelihood ratio (LR) difference tests for nested models. The LR statistic is −2 times the difference in log likelihoods, and follows a χ2 distribution with df equal to the difference in the number of estimated parameters. Also, with the Mplus “MLR” estimator, the LR statistic must be divided by a term that is a function of the number of estimated parameters in each model and the scaling correction factors given by Mplus. This was carried out as shown in an example given on the Mplus website (http://www.statmodel.com/chidiff.shtml).

To test studied item j for DIF, a full model was compared to a more constrained model. In both the full and constrained models, all of the original items from the scale were used, and items assigned to the DIF-free subset were not regressed on any grouping variables. In the full model, all studied items were permitted to have DIF (i.e., all studied items were regressed on all grouping variables). In the constrained model, invariance was presumed for item j (i.e., item j was not regressed on any grouping variables). A significant difference between these models indicates that fit significantly declines if item j is assumed DIF-free. Therefore, item j has DIF.

An alternative approach is to compare a model that presumes no DIF in any item to a model that permits DIF for studied item j. This was not done because the LR statistic follows a χ2 distribution more closely when the baseline model fits the data as closely as possible. A model presuming no DIF in any item is probably rather far from reality. Stark et al. (2006) recently discussed this issue in the context of multiple-group DIF testing.

To control the false discovery rate, the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) procedure was applied within each SNAP scale (see also Thissen et al. 2002; Williams et al. 1999). The MULTTEST procedure in SAS was used to obtain Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values for the LR statistics which are compared to α=.05 instead of the raw p-values.

Final Model

A final MIMIC model was constructed for each SNAP scale, in which only items that showed significant DIF were regressed on the grouping variables. The factor was also regressed on the grouping variables. The final model provides estimates of aj, τj, group mean differences on the factor (γk), and DIF effects (βjks). A negative βjk indicates that τj is smaller for the focal group (women, African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, Native Americans, or “other”s) than for the corresponding reference group (men or whites). In other words, the level of the latent variable required for recruits to respond “True” to the item was lower for members of the focal group. A positive βjk indicates that τj is larger for the focal group.

One τj will be reported for each item. For items without DIF, this τj applies to all participants. For differentially-functioning (D-F) items, this τj applies only to white men (i.e., when all covariates = 0), because there is a separate τj for each of the 12 groups (white men, white women, African American men, African American women, etc.). The τj for the other 11 groups may be calculated by adding the regression parameter(s) for the corresponding DIF effect(s) to the τj for white men. An example of this computation is provided when specific results are described. Example item response functions (IRFs) are also presented, which are given by Equation (1) and show the probability of responding “True” as a function of a person’s level of the factor (and the item parameters). D-F items have a separate IRF for each of the 12 groups.

Results

Table 1: Entitlement

Table 1.

Item parameter estimates and tests for differential item functioning: Entitlement (16 items)

| Item | χ2(6) | p | pBH | a (SE) | τ (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 83. I am not unusually talented. (R) | 54.83 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.42 (.06) | ◆−0.07 (.07) |

| 125. Things go best when people do things the way I do them or want them done. | 39.20 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.65 (.06) | ◆0.52 (.07) |

| 71. I am usually right. | 25.96 | .0002 | .0011 | 0.72 (.06) | ◆−0.48 (.07) |

| 120. I have many qualities that others wish they had. | 18.92 | .0043 | .0161 | 0.98 (.08) | ◆−1.01 (.09) |

| 90. People who are supposed to be experts often don’t know any more than I do. | 13.21 | .0398 | .1095 | 0.30 (.05) | 0.27 (.05) |

| 215. I’m nobody special. (R) | 12.95 | .0438 | .1095 | 1.34 (.11) | −1.69 (.09) |

| 171. I think I am quite an extraordinary person. | 12.46 | .0525 | .1124 | 1.50 (.10) | −0.88 (.08) |

| 203. I deserve more than I am getting. | 9.76 | .1353 | .2537 | 1.37 (.09) | 0.72 (.08) |

| 167. I deserve special privileges. | 8.74 | .1890 | .3149 | 3.19 (.27) | 2.86 (.23) |

| 143. I deserve special recognition. | 7.86 | .2486 | .3528 | 2.77 (.20) | 2.55 (.18) |

| 179. All I have to do is smile and people give me my way. | 7.73 | .2587 | .3528 | 0.77 (.08) | 1.91 (.08) |

| 226. I don’t deserve special privileges. (R) | 6.89 | .3311 | .3923 | 1.40 (.09) | 0.03 (.07) |

| 113. I deserve the best. | 6.80 | .3400 | .3923 | 1.92 (.18) | −3.53 (.19) |

| 132. I deserve all that I have and more. | 5.12 | .5291 | .5669 | 1.63 (.12) | −1.68 (.10) |

| 155. I deserve to be admired. | 1.24 | .9749 | .9749 | 2.49 (.16) | 0.55 (.11) |

| 49. I am a very special person. | - | - | - | 1.64 (.18) | −3.17 (.18) |

(R) = reverse scored; pBH = adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure; α=.05; a = estimated discrimination; τ = estimated threshold;

applies to white males only;—item was in DIF-free subset.

The group mean level of Entitlement was significantly larger for African American versus white recruits (γ2=0.52, SE=.06) and for Hispanic versus white recruits (γ4=0.38, SE=.15). As shown in Table 1, one Entitlement item (number 49) qualified for assignment to the DIF-free subset; all others were tested for DIF. Table 1 lists the items (ordered by LR statistic), with the LR statistic, raw p-value, and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value (pBH). Four items printed in bold type have uniform DIF (pBH is less than .05). Item parameter estimates from the final model are also listed in Table 1. Remember that the τj for D-F items applies to white male recruits only.

For D-F items, group differences in τj (i.e., βjks) are given in Table 6. An asterisk flags significant effects (α=.05). Controlling ethnicity, all four items were more easily endorsed by women than men. Holding sex constant, the threshold for item 83 was larger for African Americans and “other”s compared to whites. In contrast, τj for item 120 was much lower for Asian versus white recruits, and τj for item 125 was lower for African Americans and Hispanics compared to whites.

Table 6.

Uniform DIF effects (with SE) for differentially-functioning SNAP items

| Scale | Item | Female | Afr. Am. | Asian | Hispanic | Nat. Am. | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ent | 71 | *−0.57 (.10) | −0.14 (.14) | −0.08 (.26) | −0.17 (.26) | 0.59 (0.53) | −0.08 (.16) |

| Ent | 83 | *−0.63 (.10) | *0.32 (.13) | 0.10 (.27) | 0.35 (.24) | 0.67 (0.54) | *0.36 (.16) |

| Ent | 120 | *−0.46 (.11) | 0.26 (.16) | *−1.14 (.33) | 0.00 (.30) | 0.45 (0.66) | −0.25 (.18) |

| Ent | 125 | *−0.60 (.11) | *−0.44 (.14) | 0.00 (.27) | *−0.59 (.27) | 0.48 (0.54) | −0.11 (.16) |

| Exh | 57 | *−0.67 (.13) | *−0.62 (.16) | −0.10 (.35) | −0.41 (.29) | −0.77 (0.82) | −0.31 (.20) |

| Exh | 69 | *−0.65 (.14) | *−0.49 (.17) | −0.27 (.40) | 0.06 (.32) | −0.92 (1.17) | −0.08(.22) |

| Exh | 93 | 0.12 (.11) | *0.43 (.14) | 0.01 (.32) | −0.01 (.31) | −0.44 (0.73) | *0.53 (.18) |

| Exh | 137 | *0.55 (.11) | −0.12 (.15) | −0.30 (.26) | 0.05 (.28) | 0.28 (0.62) | −0.14 (.16) |

| Exh | 145 | 0.07 (.11) | *−0.60 (.15) | −0.10 (.28) | −0.39 (.30) | −0.28 (0.58) | −0.32 (.18) |

| Exh | 169 | *−0.97 (.11) | −0.24 (.15) | 0.03 (.31) | −0.20 (.28) | 0.30 (0.54) | 0.20 (.17) |

| Exh | 195 | −0.01 (.11) | *0.90 (.14) | 0.37 (.29) | *0.79 (.24) | 0.47 (0.50) | 0.17 (.17) |

| Exh | 223 | −0.07 (.13) | *0.56 (.16) | 0.66 (.34) | 0.54 (.30) | 0.17 (0.74) | 0.40 (.20) |

| Dis | 4 | *0.65 (.11) | *−0.35 (.14) | −0.34 (.28) | −0.35 (.27) | - | *−0.35 (.17) |

| Dis | 25 | *−1.00 (.14) | 0.25 (.16) | −0.70 (.39) | 0.08 (.32) | - | 0.13 (.20) |

| Dis | 33 | 0.14 (.23) | *1.00 (.28) | 0.71 (.50) | 0.51 (.46) | - | 0.58 (.34) |

| Dis | 34 | *0.27 (.11) | −0.28 (.15) | *−0.83 (.31) | −0.52 (.27) | - | *−0.60 (.17) |

| Dis | 37 | *−0.55 (.13) | *−1.04 (.20) | 0.14 (.32) | −0.48 (.31) | - | *−0.49 (.20) |

| Dis | 57 | *−0.55 (.11) | −0.22(.14) | −0.50 (.31) | −0.44 (.28) | - | *−0.32 (.16) |

| Dis | 99 | *−0.29 (.12) | *−0.36 (.16) | −0.39 (.29) | 0.29 (.26) | - | −0.05 (.18) |

| Dis | 117 | *−1.02 (.15) | −0.33 (.20) | 0.33 (.33) | −0.08 (.36) | - | −0.30 (.22) |

| Dis | 164 | 0.19 (.10) | *0.82 (.14) | 0.47 (.28) | *0.59 (.28) | - | 0.30 (.15) |

| Dis | 173 | *0.66 (.19) | *−1.17 (.33) | −0.95 (.68) | −0.28 (.41) | - | −0.36 (.31) |

| Dis | 200 | *−0.51 (.17) | *0.41 (.20) | 0.08 (.41) | −0.02 (.39) | - | −0.16 (.27) |

| Dis | 204 | −0.28 (.23) | 0.52 (.27) | 0.43 (.52) | −0.53 (.62) | - | *1.01 (.30) |

| Dis | 208 | *−0.49 (.12) | 0.17 (.15) | −0.46 (.29) | −0.22 (.28) | - | −0.22 (.18) |

| Dis | 247 | *0.51 (.13) | −0.10 (.17) | −0.08 (.34) | −0.07 (.33) | - | −0.22 (.20) |

| Dis | 251 | *−0.73 (.12) | *−0.82 (.17) | *−1.00 (.39) | −0.50 (.31) | - | −0.23 (.18) |

| Dis | 254 | 0.20 (.17) | *−1.40 (.28) | −0.87 (.51) | −0.39 (.33) | - | −0.16 (.26) |

| Dis | 261 | 0.18 (.14) | 0.24 (.19) | *1.70 (.32) | *0.95 (.31) | - | *0.75 (.21) |

| Dis | 268 | *−0.91 (.16) | *−0.46 (.21) | −0.02 (.35) | −0.60 (.36) | - | 0.05 (.20) |

| Dis | 272 | *−0.48 (.15) | *−0.51 (.22) | −0.15 (.40) | −0.36 (.35) | - | 0.09 (.22) |

| Dis | 282 | *−0.48 (.12) | *−0.74 (.17) | −0.17 (.35) | 0.08 (.28) | - | −0.26 (.18) |

| Dis | 307 | *0.90 (.13) | *−0.64 (.18) | −0.30 (.37) | 0.21 (.30) | - | 0.11 (.19) |

| Dis | 326 | *−0.24 (.11) | *−0.50 (.15) | 0.09 (.29) | −0.50 (.26) | - | *−0.47 (.18) |

| Neg | 245 | *0.51 (.12) | 0.10 (.17) | −0.10 (.33) | 0.03 (.32) | - | 0.00 (.19) |

| Neg | 250 | *0.36 (.13) | *−0.40 (.17) | −0.01 (.32) | −0.02 (.32) | - | −0.20 (.20) |

| Neg | 252 | −0.22 (.18) | *1.09 (.21) | *1.18 (.42) | 0.19 (.46) | - | 0.32 (.29) |

| Neg | 260 | *0.61 (.16) | 0.29 (.21) | 0.13 (.46) | −0.88 (.59) | - | *0.52 (.25) |

| Neg | 290 | −0.19 (.12) | 0.24 (.16) | *1.04 (.30) | −0.16 (.31) | - | *0.51 (.17) |

| Neg | 301 | *−0.30 (.13) | *−0.87 (.17) | −0.06 (.39) | −0.55 (.33) | - | *−0.42 (.20) |

| Neg | 316 | *−0.24 (.12) | *0.59 (.15) | *0.85 (.30) | *0.61 (.30) | - | *0.78 (.18) |

| Neg | 320 | *0.36 (.13) | −0.31 (.17) | −0.72 (.41) | −0.08 (.27) | - | −0.05 (.20) |

| Neg | 323 | *0.57 (.13) | −0.03 (.16) | −0.49 (.29) | −0.05 (.32) | - | −0.23 (.18) |

| Neg | 325 | −0.16 (.12) | *0.66 (.16) | *0.87 (.31) | 0.27 (.28) | - | *0.45 (.17) |

| Wor | 1 | *0.42 (.11) | *0.61 (.14) | 0.36 (27.) | −0.40 (.33) | - | *0.64 (.17) |

| Wor | 79 | 0.04 (.13) | *0.56 (.16) | 0.58 (.32) | −0.47 (.42) | - | −0.08 (.21) |

| Wor | 111 | −0.23 (.12) | *−0.53 (.16) | *−0.70 (.34) | −0.53 (.31) | - | *−0.47 (.20) |

| Wor | 234 | *−0.42 (.10) | *0.32 (.13) | *0.80 (.26) | 0.22 (.23) | - | 0.22 (.15) |

significantly different from men or whites; α=.05; – = Native Americans were combined with “other”s.

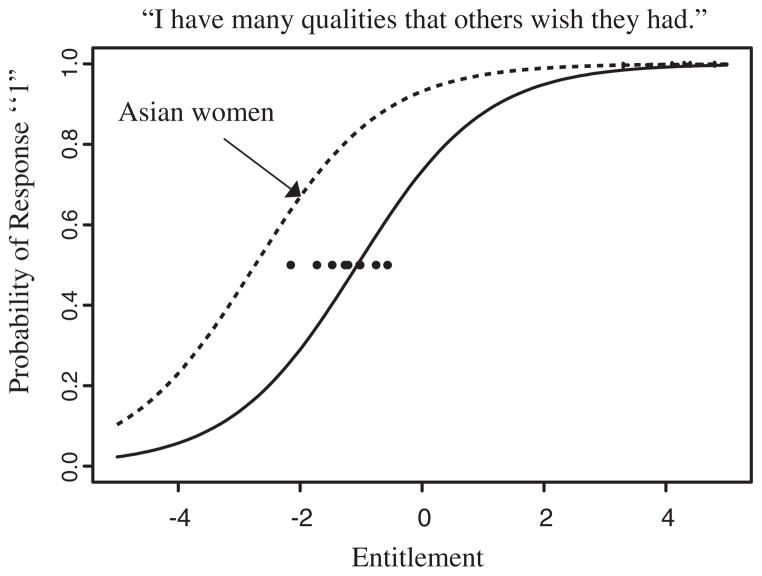

Focusing on item 120 (“I have many qualities others wish they had”) as an example, τj may be computed for each group. For African American male recruits, β2 is added to the τj for white male recruits given in Table 1: −1.01+0.26=−0.75. For Asian male recruits, β3 is used instead: −1.01 −1.14=−2.15. For Hispanic, Native American, and “other” men, this calculation would use β4, β5, and β6. To obtain thresholds for women, β1 is included in the addition. The threshold is −1.01 −0.46=−1.47 for white female recruits, and −1.01 − 0.46+0.26=−1.21 for African-American female recruits. The thresholds for women in other ethnic groups are calculated analogously.

For item 120, Fig. 2 displays the IRF for white men (solid line) and for the group that differs most from them: Asian women (dashed line). Dots are plotted at probability = .5 to indicate the value of τj for each of the other ten groups. The full IRF is not shown for the other groups to simplify the graph. Because MIMIC models do not permit group differences in aj, the IRF is the same shape for each group, just shifted over on the latent axis according to τj.

Fig. 2.

For Entitlement item 120, the solid line is the item response function (IRF) for white men, and the dashed line is the IRF for the group that differs most from white men: Asian women. Dots locate the thresholds for all additional groups

Table 2: Exhibitionism

Table 2.

Item parameter estimates and tests for differential item functioning: Exhibitionism (16 items)

| Item | χ2(6) | P | pBH | a (SE) | τ (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 169. I dress to attract sexual attention. | 60.93 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 1.15 (.08) | ◆−0.61 (.09) |

| 195. I love to have my picture taken. | 55.01 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 1.01 (.07) | ◆0.39 (.08) |

| 137. When I talk, my voice is less expressive than most people’s. (R) | 33.44 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.76 (.07) | ◆−0.75 (.08) |

| 57. I like to show off. | 25.81 | .0002 | .0008 | 1.52 (.10) | ◆0.13 (.09) |

| 93. I really enjoy speaking in public. | 19.34 | .0036 | .0089 | 1.14 (.08) | ◆0.86(.09) |

| 223. I wear clothes that draw attention. | 19.22 | .0038 | .0089 | 1.45 (.10) | ◆1.35(.10) |

| 145. I never attempt to be the life of the party. (R) | 15.44 | .0171 | .0341 | 1.20 (.08) | ◆−0.10 (.08) |

| 69. I like being the topic of conversation. | 14.56 | .0239 | .0419 | 1.82 (.11) | ◆0.60 (.10) |

| 45. I don’t like to be noticed when I walk into a room. (R) | 12.71 | .0480 | .0747 | 2.11 (.14) | −1.44 (.11) |

| 108. I perform in public whenever I can. | 12.41 | .0535 | .0749 | 1.06 (.09) | 1.54 (.08) |

| 19. I’m no good at flirting. (R) | 12.11 | .0595 | .0758 | 1.15 (.08) | −1.08 (.07) |

| 183. I like to turn heads when I walk into a room. | 10.34 | .1109 | .1293 | 2.78 (.19) | −0.57 (.12) |

| 6. I hate it when the topic of conversation turns to me. (R) | 7.07 | .3141 | .3383 | 0.84 (.08) | −1.54 (.07) |

| 217. I love to flirt. | 6.10 | .4124 | .4124 | 1.44 (.09) | −0.51 (.08) |

| 28. I like people to notice how I look when I go out in public. | - | - | - | 1.48 (.10) | −1.40 (.09) |

| 82. I don’t enjoy being in the spotlight. (R) | - | - | - | 2.11 (.13) | −0.31 (.10) |

(R) = reverse scored; pBH = adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; α=.05; a = estimated discrimination; τ = estimated threshold;

applies to white males only;—item was in DIF-free subset.

Two items were assigned to the DIF-free subset for Exhibitionism. Results listed in Table 2 show that eight items displayed significant DIF. Details are given in Table 6. Men and women differed on four items, African American and white recruits differed on six items, and there was one Hispanic-white difference and one “other”-white difference. The mean level of Exhibitionism was significantly lower for women than men (γ1= −0.14, SE=.05) and for Asians versus whites (γ3= −0.36, SE=.14).

Table 3: Disinhibition

Table 3.

Item parameter estimates and tests for differential item functioning: Disinhibition (35 items)

| Item | χ2(5) | p | pBH | a (SE) | τ (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 251. If I had to choose, I would prefer having to sit through a long concert of music I dislike to being in a bank during an armed robbery. (R) | 71.72 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.57 (.07) | ◆0.73 (.08) |

| 25. I would not use others’ weaknesses to my own advantage. (R) | 61.53 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.89 (.08) | ◆1.09 (.09) |

| 307. I am a serious-minded person. (R) | 50.25 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.98 (.98) | ◆1.64 (.10) |

| 268. I get a kick out of really scaring people. | 47.98 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.94 (.08) | ◆1.44 (.10) |

| 164. I don’t ever like to stay in one place for long. | 45.09 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.51 (.06) | ◆−0.05 (.07) |

| 117. I’ve done a lot of things for which I could have been (or was) arrested. | 44.99 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 1.29 (.09) | ◆1.26 (.10) |

| 37. I rarely, if ever, do anything reckless. (R) | 43.76 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 1.21 (.09) | ◆0.83 (.09) |

| 261. I work just hard enough to get by. | 36.42 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 1.23 (.10) | ◆2.26 (.12) |

| 4. I am not an “impulse buyer.” (R) | 36.30 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.77 (.06) | ◆0.57 (.08) |

| 57. I like to show off. | 34.07 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.69 (.06) | ◆0.10 (.07) |

| 282. I would much rather party than work. | 26.68 | <.0001 | .0002 | 1.39 (.09) | ◆−0.31 (.09) |

| 208. I really enjoy beating the system. | 23.16 | .0003 | .0008 | 0.87 (.07) | ◆0.69 (.08) |

| 254. Before making a decision, I carefully consider all sides of the issue. (R) | 19.43 | .0016 | .0038 | 1.79 (.13) | ◆2.32 (.15) |

| 326. I spend a good deal of my time just having fun. | 19.02 | .0019 | .0042 | 0.97 (.07) | ◆0.04 (.08) |

| 33. When I resent having to do something, I sometimes make mistakes on purpose. | 18.17 | .0027 | .0057 | 1.22 (.14) | ◆3.84 (.23) |

| 272. If I had to choose, I would prefer being in a flood to unloading a ton of newspapers from a truck. | 17.39 | .0038 | .0074 | 0.70 (.08) | ◆1.70 (.10) |

| 204. The way I behave often gets me into trouble on the job, at home, or at school. | 17.14 | .0043 | .0077 | 1.86 (.17) | ◆3.71 (.23) |

| 173. I usually use careful reasoning when making up my mind. (R) | 16.64 | .0052 | .0090 | 1.88 (.14) | ◆3.08 (.18) |

| 34. I believe in playing strictly by the rules. (R) | 16.09 | .0066 | .0108 | 1.21 (.08) | ◆−0.00 (.08) |

| 200. I would never hurt other people just to get what I want. (R) | 14.72 | .0016 | .0180 | 0.45 (.09) | ◆2.14 (.11) |

| 99. I like to take chances on something that isn’t sure, such as gambling. | 13.89 | .0163 | .0241 | 0.94 (.07) | ◆0.67 (.08) |

| 247. I often stop in the middle of one activity to start another one. | 12.33 | .0305 | .0430 | 1.15 (.09) | ◆1.55 (.10) |

| 186. I often get out of doing things by making up good excuses. | 11.45 | .0432 | .0582 | 1.53 (.12) | 2.77 (.13) |

| 318. When I’m having a good time, I don’t worry about the consequences. | 11.03 | .0507 | .0655 | 1.61 (.11) | 1.65 (.10) |

| 130. I am a cautious person. (R) | 10.18 | .0702 | .0871 | 1.26 (.10) | 2.24 (.10) |

| 232. I have stolen things from time to time. | 9.38 | .0947 | .1130 | 1.22 (.09) | 1.69 (.09) |

| 160. I greatly dislike it when someone breaks accepted rules of good behavior. (R) | 8.53 | .1296 | .1487 | 0.72 (.07) | 1.13 (.06) |

| 198. I don’t keep particularly close track of where my money goes. | 7.13 | .2111 | .2337 | 1.13 (.08) | 1.13 (.07) |

| 91. Lying comes easily to me. | 6.92 | .2270 | .2426 | 1.49 (.10) | 2.02 (.10) |

| 329. Taking care of details is not my strong point. | 5.20 | .3921 | .4052 | 1.00 (.08) | 1.10 (.07) |

| 124. When I decide things, I always refer to the basic rules of right and wrong. (R) | 4.95 | .4220 | .4220 | 1.21 (.10) | 1.91 (.09) |

| 88. I’ll take almost any excuse to goof off instead of work. | - | - | - | 2.25 (.20) | 4.17 (.25) |

| 154. I always try to be fully prepared before I begin working on anything. (R) | - | - | - | 1.30 (.12) | 3.18 (.14) |

| 168. I’ve been told that I work too hard. (R) | - | - | - | 0.52 (.06) | −0.29 (.05) |

| 220. I get the most fun out of things that others think are immoral or illegal. | - | - | - | 1.84 (.15) | 3.31 (.17) |

(R) = reverse scored; pBH = adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure; α=.05; a = estimated discrimination; τ = estimated threshold;

applies to white males only; - item was in DIF–free subset.

Four Disinhibition items were assigned to the DIF-free subset (see Table 3). Twenty-two items had significant DIF. As shown in Table 6, women differed from men on 17 items. Differences from whites were observed on 14 items for African Americans, seven items for “other”s, 3 items for Asians, and two items for Hispanics. The mean level of disinhibition was significantly lower for female versus male recruits (γ1= −0.21, SE=.06) and for African American versus white recruits (γ2= −0.18, SE=08).

Table 4: Negative Temperament

Table 4.

Item parameter estimates and tests for differential item functioning: Negative Temperament (28 items)

| Item | χ2(5) | p | pBH | a (SE) | τ (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301. Sometimes I feel “on edge” all day. | 39.57 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 1.92 (.11) | ◆0.63 (.11) |

| 316. I worry about terrible things that might happen. | 27.73 | <.0001 | .0004 | 1.55 (.09) | ◆0.66 (.10) |

| 323. I have days that I’m very irritable. | 27.09 | .0001 | .0004 | 1.15 (.08) | ◆−1.15 (.09) |

| 252. My anger frequently gets the better of me. | 26.47 | .0001 | .0004 | 1.58 (.13) | ◆3.30 (.18) |

| 325. Often life feels like a big struggle. | 21.78 | .0006 | .0023 | 1.60 (.09) | ◆0.12 (.09) |

| 260. Sometimes I suddenly feel scared for no good reason. | 20.94 | .0008 | .0028 | 1.98 (.15) | ◆3.44 (.20) |

| 245. My mood sometimes changes (for example, from happy to sad, or vice versa) without good reason. | 18.76 | .0021 | .0061 | 1.66 (.10) | ◆1.46 (.11) |

| 290. I am sometimes troubled by thoughts or ideas that I can’t get out of my mind. | 16.31 | .0060 | .0151 | 1.68 (.09) | ◆0.26 (.10) |

| 250. I frequently find myself worrying about things. | 14.52 | .0127 | .0277 | 1.96 (.11) | ◆−0.18 (.11) |

| 320. I worry too much about things that don’t really matter. | 14.30 | .0138 | .0277 | 1.94 (.11) | ◆1.22 (.12) |

| 331. Things seem to bother me less than most other people. (R) | 12.66 | .0268 | .0487 | 0.56 (.06) | 0.68 (.05) |

| 244. I sometimes get too upset by minor setbacks. | 10.61 | .0567 | .0817 | 1.55 (.09) | 0.28 (.08) |

| 259. Little things upset me too much. | 10.56 | .0608 | .0817 | 2.03 (.12) | 1.46 (.11) |

| 274. I often take my anger out on those around me. | 10.56 | .0608 | .0817 | 1.32 (.10) | 2.42 (.11) |

| 312. I seem to be able to remain calm in almost any situation. (R) | 10.43 | .0640 | .0817 | 0.95 (.08) | 1.92 (.08) |

| 273. I can get very upset when little things don’t go my way. | 10.37 | .0653 | .0817 | 1.75 (.11) | 1.82 (.10) |

| 333. I sometimes feel angry for no good reason. | 7.79 | .1684 | .1981 | 2.10 (.13) | 2.39 (.14) |

| 248. I often feel nervous and “stressed.” | 6.53 | .2578 | .2864 | 2.11 (.12) | 1.06 (.10) |

| 281. I often worry about things I have done or said. | 5.48 | .3604 | .3793 | 1.50 (.09) | −0.90 (.08) |

| 269. I am often nervous for no reason. | 4.09 | .5369 | .5369 | 2.42 (.16) | 3.14 (.17) |

| 241. I often have strong feelings such as anxiety or anger without really knowing why. | - | - | - | 1.92 (.11) | 1.80 (.11) |

| 264. I sometimes get all worked up as I think about things that happened during the day. | - | - | - | 1.53 (.08) | 0.12 (.08) |

| 277. I would describe myself as a tense person. | - | - | - | 1.64 (.10) | 1.85 (.10) |

| 288. Sometimes life seems pretty confusing to me. | - | - | - | 1.30 (.08) | −0.66 (.07) |

| 294. I often have trouble sleeping because of my worries. | - | - | - | 1.86 (.11) | 2.12 (.12) |

| 298. I don’t get very upset when things go wrong. (R) | - | - | - | 1.01 (.07) | 0.51 (.06) |

| 309. Small annoyances often irritate me. | - | - | - | 1.23 (.07) | −0.17 (.07) |

| 311. I am often troubled by guilt feelings. | - | - | - | 1.41 (.09) | 1.66 (.09) |

(R) = reverse scored; pBH = adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; α=.05; a = estimated discrimination; τ = estimated threshold;

applies to white males only;—item was in DIF-free subset.

The DIF-free subset consisted of eight items for Negative Temperament, and there were 10 D-F items (see Table 4). As apparent from Table 6, there were gender differences on seven items, and differences from whites for African Americans on five items, “other”s on five items, Asians on four items, and Hispanics on one item. Controlling ethnicity, the factor mean was significantly greater for female versus male recruits (γ1=0.16, SE=05).

Table 5: Workaholism

Table 5.

Item parameter estimates and tests for differential item functioning: Workaholism (18 items)

| Item | χ2(5) | p | pBH | a (SE) | τ (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I enjoy work more than play. | 48.28 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.91 (.07) | ◆1.54 (.09) |

| 234. I sometimes have a hard time finishing things because I want them to be perfect. | 31.36 | <.0001 | <.0001 | 0.66 (.06) | ◆0.12 (.07) |

| 111. People say that I drive myself hard. | 24.38 | .0002 | .0006 | 1.89 (.13) | ◆−0.13 (.10) |

| 79. My work is more important to me than anything else. | 15.60 | .0081 | .0202 | 1.03 (.09) | ◆2.03 (.11/) |

| 127. I never get so caught up in my work that I neglect my family or friends. (R) | 12.41 | .0296 | .0593 | 0.87 (.09) | 1.70 (.08) |

| 68. Even when I have done something very well, I usually demand that I do better next time. | 11.28 | .0461 | .0768 | 1.29 (.10) | −1.71 (.09) |

| 227. No matter how busy I am, I always find some time to have fun. (R) | 10.27 | .0680 | .0971 | 0.44 (.08) | 1.80 (.07) |

| 18. People say I neglect other important parts of my life because I work so hard. | 9.27 | .0987 | .1214 | 1.97 (.16) | 2.64 (.15) |

| 192. I push myself to my limits. | 8.87 | .1145 | .1214 | 1.24 (.09) | −1.24 (.08) |

| 180. I don’t consider a task finished until it’s perfect. | 8.71 | .1214 | .1214 | 1.36 (.10) | −1.44 (.09) |

| 29. When I start a task, I am determined to finish it. | - | - | - | 1.27 (.14) | −3.03 (.15) |

| 47. I put my work ahead of being with my family or friends. | - | - | - | 1.04 (.08) | 0.56 (.06) |

| 54. I often keep working on a problem even if I am very tired. | - | - | - | 1.26 (.10) | −1.49 (.08) |

| 116. I often keep working on a problem long after others have given up. | - | - | - | 1.47 (.11) | −1.60 (.09) |

| 168. I’ve been told that I work too hard. | - | - | - | 2.48 (.18) | 0.55 (.11) |

| 187. Some people say that I put my work ahead of too many other things. | - | - | - | 2.55 (.21) | 2.27 (.17) |

| 211. People sometimes tell me to slow down and “take it easy.” | - | - | - | 1.20 (.08) | −0.20 (.06) |

| 214. I enjoy working hard. | - | - | - | 1.40 (.11) | −2.10 (.10) |

(R) = reverse scored; pBH = adjusted to control the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure; α=.05; a = estimated discrimination; τ = estimated threshold;

applies to white males only;—item was in DIF-free subset.

Eight items were assigned to the DIF-free subset for Workaholism, and there were four D-F items (see Table 5). As shown in Table 6, African Americans differed from whites on all four items, and men differed from women on two items. Differences from whites were also observed for Asian recruits on two items and “other”s on two items. The mean level of workaholism was significantly greater for “other”s than whites (γ6=0.21, SE=.08).

Discussion

This research illustrated how MIMIC models may be used to test for DIF with binary item response scales. The methodology (and software used here) also applies straightforwardly to items with ordinal (Likert-type) response scales. Hopefully, examples of methodology for testing DIF will help to increase the frequency with which researchers apply these procedures to other scales and samples in pursuit of eliminating measurement bias in psychology.

Future research with additional samples is needed because the pattern of DIF, and the parameter estimates, observed for Air Force recruits may not be the same for other samples. These Air Force recruits are similar to many college samples with respect to age and ethnicity, but more heterogeneous with respect to education and intelligence. There were more men in this sample than in many samples obtained through psychology participant pools. Also, there may be personality differences between college students and young adults who self-select into the Air Force. The present study focused on 5 SNAP scales that appeared to show differential test functioning in a previous analysis with the same data. With other samples, some of the other 9 SNAP trait and temperament scales or 13 SNAP diagnostic scales should be examined.

The relatively small sample sizes for specific ethnic minority groups was a limitation of this study which led to the choice of MIMIC modeling instead of IRT-LR-DIF. MIMIC modeling has advantages (mentioned earlier), but one disadvantage is that only uniform, not nonuniform DIF, is tested. Also, simulations have suggested that with focal-group sample sizes less than about 100, parameter estimates in models with many parameters (as in the final models used here), are likely to be less accurate than with larger focal groups (Woods, in press). A warranted aim for the future is to assess DIF on SNAP items with larger focal-group sample sizes, either with MIMIC modeling, or with IRT-LR-DIF, if possible.

Keeping in mind these limitations and qualifications, the present results suggested that some SNAP items functioned differently for different demographic groups. Although a person’s probability of endorsing an item should depend only on their level of the latent variable and qualities of the items, responses to some SNAP items also depended on gender, ethnicity, or both. The DIF effects for some items were huge. These findings imply that scores on these five SNAP scales do not mean the same thing for all Air Force recruits.

D-F items have been observed on many psychological scales. Waller et al. (2000) found that many items on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI; Hathaway and McKinley 1940) functioned differently for black versus white respondents, and opined that “any omnibus inventory… is likely to contain numerous items that perform differently across various homogeneous groups” (p. 142). Perhaps this has happened because some instruments were written before methods for testing DIF were well developed or widely available, and many others were simply created without attention to the possibility of DIF.

One obvious strategy for eliminating DIF is to revise or delete D-F items on extant scales, and to routinely test for DIF when new measures are constructed. As part of this, it will be useful to understand causes of DIF. Surely group membership is a proxy for some other (probably continuous) variables. For example, in the present study, it is unclear why Asian women more readily reported having “many qualities others wish they had” such that this SNAP item was not as strongly indicative of Entitlement for them as it was for white men. Were Asian women actually more talented in some way? The present findings raise many questions of this sort that could be explored in future research.

Another way of managing DIF is to model it. For example, group mean differences on SNAP scales that have D-F items could be estimated with the DIF modeled using a MIMIC or multiple-group model. As in the final model fitted in the present study, parameters for D-F items would be estimated separately for each group, whereas parameters for invariant items would be held equal across groups. Such a model gives an estimate of the mean difference with DIF taken into consideration. Scores for each individual could be computed from these models as well. Although it might be ideal to have DIF-free instruments, modeling DIF can certainly help to reduce the proliferation of misleading results.

Footnotes

Uniform DIF occurs when item thresholds differ between groups: An item is more easily endorsed for one group than the other. DIF is nonuniform if item discrimination also differs between groups; thus, the group difference depends on the level of the latent variable.

Because each scale is evaluated for DIF separately from the other scales, it is not problematic for a SNAP item to be included on more than one scale.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum A. Some latent trait models. In: Lord FM, Novick MR, editors. Statistical theories of mental test scores. Reading, MA: Addison & Wesley; 1968. pp. 395–479. [Google Scholar]

- Camilli G, Shepard LA. Methods for identifying biased test items. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Clark L. SNAP Manual for administration, scoring, and interpretation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Finch H. The MIMIC model as a method for detecting DIF: comparison with Mantel-Haenszel, SIBTEST, and the IRT likelihood ratio. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2005;29:278–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. A multiphasic personality schedule (Minnesota): I. Construction of the schedule. Journal of Psychology. 1940;10:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Holland PW, Wainer H. Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntosh R, Hashim S. Variance estimation for converting MIMIC model parameters to IRT parameters in DIF analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2003;27:372–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mellenbergh GJ. Item bias and item response theory. International Journal of Educational Research. 1989;13:127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE, Everson HT. Methodology review: statistical approaches for assessing measurement bias. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1993;17:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. A method for studying the homogeneity of test items with respect to other relevant variables. Journal of educational statistics. 1985;10:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Some uses of structural equation modeling in validity studies: Extending IRT to external variables. In: Wainer H, Braun HI, editors. Test Validity. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO. Latent variable modeling in heterogeneous populations. Psychometrika. 1989;54:557–585. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Kao C, Burstein L. Instructionally sensitive psychometrics: an application of a new IRT-based detection technique to mathematics achievement test items. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1991;28:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, (Version 4.21) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Perceptions of self and others regarding pathological personality traits. In: Krueger RF, Tackett J, editors. Personality and psychopathology: Building bridges. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Simms LJ, Clark LA. Differentiating Normal & Abnormal Personality. New York: Springer; 2006. Chapter 17: The schedule for nonadaptive and adaptive personality (SNAP): A dimensional measure of traits relevant to personality and personality pathology. [Google Scholar]

- Stark S, Chernyshenko OS, Drasgow F. Detecting differential item functioning with confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Toward a unified strategy. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:1291–1306. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Gerrard M. Beyond group-mean differences: The concept of item bias. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Wainer H. Use of item response theory in the study of group difference in trace lines. In: Wainer H, Braun H, editors. Test validity. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Wainer H. Detection of differential item functioning using the parameters of item response models. In: Holland PW, Wainer H, editors. Differential item functioning. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 67–111. [Google Scholar]

- Thissen D, Steinberg L, Kuang D. Quick and easy implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for controlling the false positive rate in multiple comparisons. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2002;27:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Waller NG, Thompson JS, Wenk E. Using IRT to separate measurement bias from true group differences on homogeneous and heterogeneous scales: An illustration with the MMPI. Psychological Methods. 2000;5:125–146. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. Effects of anchor item methods on detection of differential item functioning within the family of Rasch models. The Journal of Experimental Education. 2004;72:221–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yeh Y. Effects of anchor item methods on differential item functioning detection with the likelihood ratio test. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2003;27:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- Williams VSL, Jones LV, Tukey JW. Controlling error in multiple comparisons, with examples from state-to-state differences in educational achievement. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:42–69. [Google Scholar]

- Woods CM. Evaluation of MIMIC-model methods for DIF testing with comparison to two-group analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. doi: 10.1080/00273170802620121. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CM, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Detection of aberrant responding on a personality scale in a military sample: An application of evaluating person fit with two-level logistic regression. Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:159–168. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]