Abstract

Objective

To examine the course of Eating Disorder NOS (EDNOS) compared with anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED).

Method

Prospective study of 385 participants meeting DSM-IV criteria for AN, BN, BED and EDNOS at 3 sites. Recruitment was from the community and specialty clinics. Participants were followed at 6-month intervals over a 4-year period using the Eating Disorder Examination as the primary assessment.

Results

EDNOS remitted significantly more quickly that AN or BN but not BED. There were no differences between EDNOS and full ED syndromes, or the sub-types of EDNOS, in time to relapse following first remission. Only 18% of the EDNOS group had never had or did not develop another ED diagnosis during the study, however this group did not differ from the remaining EDNOS group.

Conclusion

EDNOS appears to be a way station between full ED syndromes and recovery, and to a lesser extent from recovery or EDNOS status to a full ED. Implications for DSM-V are examined.

Introduction

Eating Disorder not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) the most common eating disorder (1–4) is a residual category composed of eating disorders that do not meet full criteria for anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN) and includes binge eating disorder (BED) as a provisional diagnosis (5). It has been noted that EDNOS is similar to BN in the nature, duration and severity of psychopathology (1–4) and in the use of health care services (6) yet it has been relatively neglected in the research literature. For example, few studies have prospectively examined the course of EDNOS compared with other eating disorders such as AN and BN. Studies comparing the course of different disorders may be helpful in distinguishing between different entities.

One comparative study with 90 participants found that 78% of an EDNOS group were recovered at 5-years follow-up with 20% having another eating disorder diagnosis. Comparable figures for AN were 59% and 14%, and for BN 74% and 18% (7). A larger study found that a higher percentage of EDNOS remitted compared with BN at 24 months follow-up (8). Another study followed 33 women with EDNOS for an average of 41 months (9). During this time 46% met criteria for a full eating disorder syndrome for at least some period of time. At the end of follow-up 12% of the EDNOS group met full criteria for either AN or BN and only 18% had recovered, suggesting that the EDNOS group was moving both toward recovery and toward a full ED syndrome.

Although these studies suggest that EDNOS recovers more quickly that AN or BN two other studies (10,11) found no differences in terms of remission between EDNOS and BN.

The present study expands previous work using a larger sample of EDNOS compared with full syndrome AN, BN, and binge eating disorder (BED) with assessments every 6-months over a 4-year period. Although BED is at present classified within the EDNOS category studies suggest that it should be regarded as a separate entity. For example, family studies suggest that BED is transmitted separately from AN and BN, that it increases the risk for obesity, and that it is a chronic and stable syndrome (12–14). Based on the literature we hypothesized that the EDNOS group would demonstrate faster rates of recovery and relapse over time as compared with full syndrome eating disorders including BED. Because EDNOS appears to be composed of a heterogeneous group of disorders, we comprised an EDNOS group for this study consisting of partial AN, BN, and BED entities that comprise the majority of the EDNOS group (15). This allowed us to consider the partial syndromes together (as EDNOS) and separately.

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted at three sites: Cornell University, Stanford University, and the University of Minnesota. Details of recruitment to this study were described in a previous publication (16). The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study and all subjects gave their written informed consent to participate.

A total of 385 individuals were entered into the study and followed for 4 years. Participants met DSM-IV criteria for AN (N=45), BN (purging type) (N= 87), BED (N=104), or for EDNOS (N=149) as noted above and defined in Table 1: Partial AN (PAN), Partial BN (PBN), or Partial BED (PBED).

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for the partial syndromes.

Partial anorexia nervosa

|

Partial bulimia nervosa

|

Partial binge eating disorder

|

Assessments

Participants were followed for 4-years with in-person interviews every 6-months and shorter telephone interviews 3-months after each in-person interview. At the in-person assessments participants were weighed (in gowns if AN) and their height was measured. Interviews consisted of the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) (17) to assess core eating disorder psychopathology and an interim telephone interview the McKnight Follow-up for Eating Disorders (M-FED). The M-FED was based on the LIFE interview (18) modified to assess eating disorder psychopathology with questions and definitions similar to those of the EDE. Hence this interview documented eating disorder symptoms and psychopathology in an abbreviated form; treatment for eating disorder or other conditions; and general psychopathology. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV for Axis I and II disorders (19) was administered at entry to the study. Assessors were trained in the administration of the EDE and M-FED at combined site meetings and were supervised on site. A random sample of EDE’s at each of the four sites was audited by independent assessors periodically throughout the course of the study. Inter-rater reliabilities were: purging 0.99; objective binge eating 0.99; eating concerns 0.98; restrained eating 0.99; shape concerns 0.97; and weight concerns 0.90.

Statistical analyses

The primary data for the analysis were derived from the semi-annual EDE interviews. If a data point was missing it was acquired from the M-FED preceding the missing data point. If the M-FED was not available, the data point was interpolated according to the following rules. If the two points on either side of the missing data point were the same value, that value was entered. However, if the data points differed, a random choice was made between the two options. Thirty-two data points were estimated in this way. The stability of diagnosis used transitional probabilities of Markov chains to determine the probability of a specific ED diagnosis given the diagnosis that occurred 6-months earlier. These eight transitional matrices were averaged to determine the mean 6-month transition between diagnoses. Between group statistical comparisons used ANOVA’s or chi-square as appropriate taking into account the effect of site. Survival curves were used to compare the time to first episode of no ED diagnosis and time to first relapse after no diagnosis for the different eating disorder types.

Remission was defined in this study as the first point after entry to the trial that the participant had no ED diagnosis during the preceding 6-months as determined by the EDE using DSM-1V criteria. Relapse was defined as the first point after a remission when symptoms for any ED diagnosis including EDNOS (as defined in Table 1) were observed as determined by the EDE.

Results

Selected baseline characteristics for the four diagnoses are shown in Table 2. A more detailed description can be found in a previous publication (16). The majority of participants in all groups had outpatient treatment for their eating disorder whereas inpatient treatment was most common for AN followed by BN.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for the 4 eating disorder groups

| AN N= 45 | BN N=87 | BED N=104 | EDNOS N=149 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.3(10.0) | 30.1(8.4) | 38.7(7.2) | 31.5(8.8) |

| BMI | 16.9(2.0) | 24.9(9.4) | 37.4(8.6) | 27.0 |

| Employed | 53% | 62% | 71% | 79% |

| Current Depression | 31% | 25% | 12% | 16% |

| Lifetime Depression | 56% | 69% | 67% | 63% |

| Personality Disorder | 49% | 47% | 24% | 32% |

| Substance use | 24% | 29% | 28% | 27% |

| Outpatient Treatment | 73% | 79% | 68% | 84% |

| Inpatient Treatment | 75% | 34% | 5% | 24% |

| Objective binges1 | 0 (.75) | 21 (18) | 14 (11) | 2 (5) |

| Purges1 | 0 (14.8) | 29 (46) | 0 (0) | 0 (5.75) |

| Self induced vomiting | 0 (1) | 26.5 (46) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Laxative use | 0 (0) | 0 (1) | 0 (2) | 0 (0) |

| EDE Restraint | 3.0(2.0) | 3.3(1.6) | 2.2(1.3) | 2.4(1.7) |

| EDE Weight Concerns | 3.2(1.8) | 3.6(1.5) | 3.6(1.1) | 2.9(1.6) |

| EDE Shape Concerns | 3.4(1.9) | 3.8(1.4) | 3.9(1.1) | 3.2(1.5) |

| EDE Eating Concerns | 2.7(1.7) | 2.7(1.4) | 2.1(1.3) | 1.8(1.4) |

Median and interquartile range

Times to remission and relapse for EDNOS compared with full syndromes

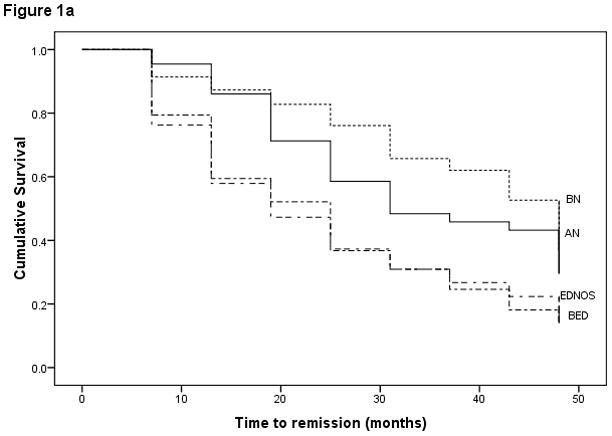

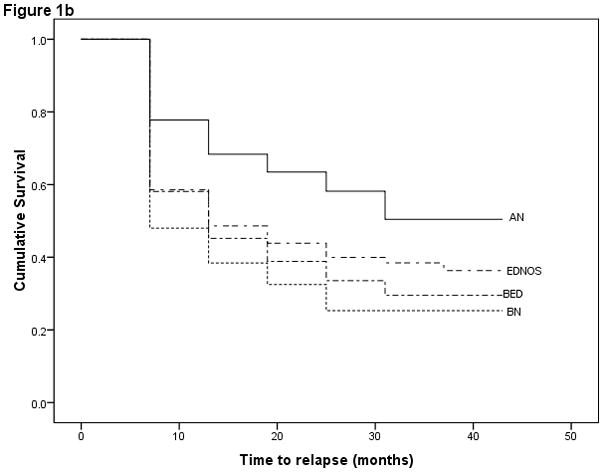

As shown in Figure 1 the time to first remission, i.e. having no ED diagnosis, differs among diagnoses W(3)=17.8, p=.000 with EDNOS and BED showing similar rates over the course of the study and having the shortest times to remission, and BN having the longest time to first remission followed by AN. At the 4-year follow-up 78% of the EDNOS group were remitted compared with 82% of the BED group, 47% of the BN group, and 57% of the AN group. Time to relapse following the first remission is also shown in Figure 1. Although the survival analysis showed no significant difference between groups, inspection of the curves suggests that BED, BN, and EDNOS had similar curves but that AN participants took longer to relapse after the first remission. Of note is the high rate of relapse in the first 6-months after remission for all groups except AN.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Survival curve showing time to first remission for EDNOS and the three full syndrome ED groups.

Figure 1b. Survival curve showing time to relapse following remission for EDNOS and the three full syndrome ED groups.

Times to remission and relapse for EDNOS sub-types

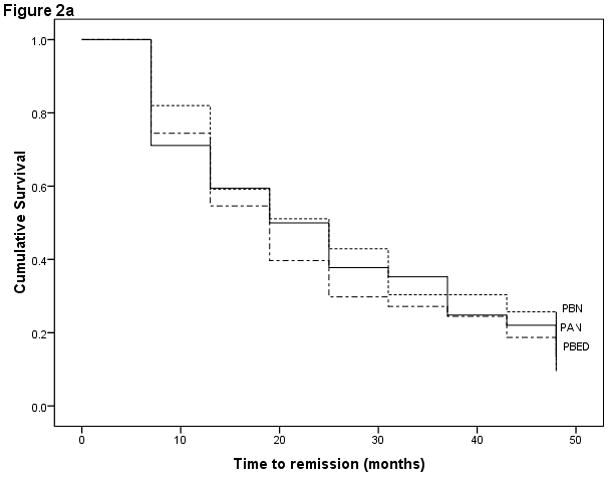

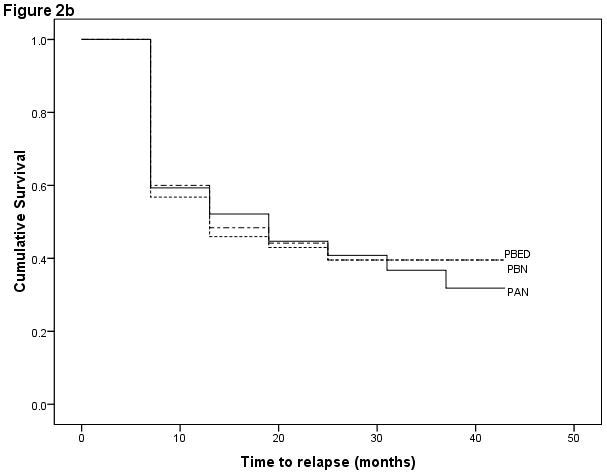

We next compared the sub-types comprising the EDNOS group, PAN, PBN, and PBED, to determine differences among them in times to first remission and relapse. As shown in Figure 2 there were no significant differences among the sub-types in time to first remission. At the 4-year follow-up 74% of the PBED group was remitted, compared with 70% of the PBN group, and 68% of the PAN group. Figure 2 also displays the survival curve for time to relapse following first remission for the 3 sub-types of EDNOS. There were no significant differences among groups and there was a high rate of relapse for all three groups in the first 6-months following remission.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Survival curve showing time to first remission for the three subcomponents of EDNOS.

Figure 2b. Survival curve showing time to relapse following remission for the three subcomponents of EDNOS.

Stability of diagnosis

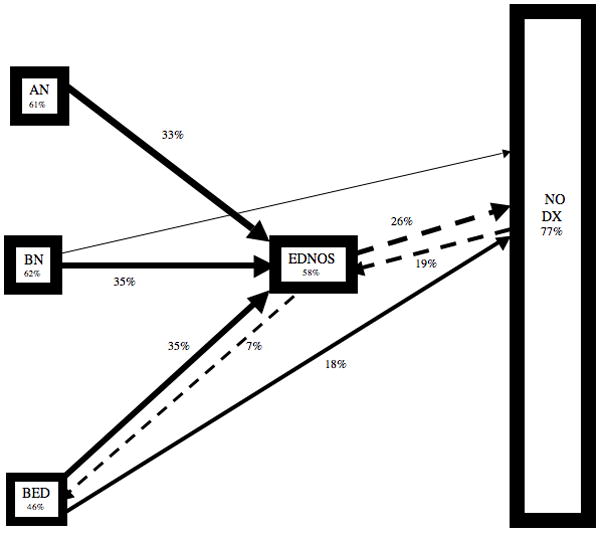

Figure 3 shows the Markov probabilities for the average 6-month diagnostic transitions less than 5% between the four diagnoses on a person basis. The four diagnoses (AN, BN, BED, and EDNOS) have similar levels of stability in terms of moving either between diagnostic categories or to no ED diagnosis. The most common pathway to remission is via the EDNOS category with relatively few cases going straight to remission. Similarly the most frequent pathway to relapse is to the EDNOS diagnosis. Hence, EDNOS appears to be largely composed of individuals most frequently on the path to remission and less frequently to relapse because the overall group is improving over time. It is noteworthy that there are no transitions over 5% between the AN, BN, and BED groups, and only a 7% average transition between EDNOS and BED and none between EDNOS and the other categories. There are, however, some transitions below the 5% level. AN transitions directly to BN in 2% of cases and to no ED diagnosis in 4%. BED transitions to BN in 1% of cases.

Figure 3.

Average 6-month transitions between diagnoses

Retrospective study of the EDNOS group

A review of past ED diagnoses for the EDNOS group determined by the SCID reveals that 78% of the EDNOS group had a past full ED diagnosis. Hence, only a minority of the group (N=37) was “pure” EDNOS at entry to the study. Over the duration of the study 10 (27%) of this group developed either AN or BN, 5 (14%) continued as EDNOS, and 22 (59%) recovered without developing another ED diagnosis. Hence, of the 149 individuals entered to the study with a diagnosis of EDNOS only 27 (18%) finished the study with no other ED diagnosis. This group did not differ in time to remission or relapse from the EDNOS group who had met criteria for a full ED syndrome. There were also no significant differences between the two groups on any baseline measure except ED symptoms.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to compare the course and stability of EDNOS compared with AN, BN, and BED. As a recent comprehensive review of the literature pointed out “virtually nothing is known about the persistence of EDNOS” (20). Yet, as many authors have noted EDNOS comprises the largest ED group, has similar psychopathology to other eating disorders particularly BN, and is accompanied by considerable disability (1, 3–5). In this study we constructed an EDNOS group from the partial syndromes of AN, BN, and BED, hence the subcomponents of EDNOS as defined in Table 1 could be examined individually.

The first question posed concerned the course of EDNOS. Hence we examined time to first remission from entry to the study. There was a significant difference in time to first remission among the four syndromes with EDNOS and BED showing the shortest and almost identical times, and BN showing the longest time followed by AN. Nearly 80% of the EDNOS group had no ED at the 4-year follow-up with a similar figure for BED. Next, time from first remission to relapse to any ED diagnosis was examined. No significant differences were found among the four groups in this analysis. Overall, these findings are similar to those of previous studies, i.e. EDNOS remits more quickly and has a higher rate of recovery over time than AN or BN (7,8). However, in the present study no differences in course were found between EDNOS and BED. As found in other studies the majority of cases from all the ED syndromes no longer have their original diagnosis at the end of the 4-year follow-up (11,21).

We next examined the time to remission and to first relapse following remission for the three subcomponents (PAN, PBN, PBED) of EDNOS. There were no statistically significant differences among these subcomponents for either time to remission or time to first relapse, suggesting identical courses.

With the exception of EDNOS as shown in Figure 3, there are few transitions from one eating disorder to another with most transitions occurring between AN and BN. These findings suggest that EDNOS is mainly composed of individuals with an ED diagnosis transitioning to no diagnosis or from no diagnosis to an eating disorder diagnosis. It is noteworthy that few individuals transition directly on average over a 6-month time interval from a full eating disorder diagnosis to no diagnosis. A retrospective study of the EDNOS group found that the majority had a full ED in the past. This is consistent with the prospective finding that patients with a full ED transition to remission via EDNOS. In addition only 18% of the EDNOS group without a full ED diagnosis recovered without developing another ED or persisted as EDNOS. However, this “pure” EDNOS group did not differ from the remaining EDNOS group in terms of times to remission or relapse or on any baseline characteristic.

Despite the strengths of this study, namely its prospective nature, frequent assessment by standard interview, and fairly large sample size, there are some limitations that need to be taken into account. The majority of participants received some form of treatment during the follow-up period specifically directed at their eating disorder. Although the proportions of individuals treated as outpatients were similar for the four groups, hospitalization was more frequent for AN than for the other groups possibly differentially affecting the course of this syndrome. It is probable that without specific ED treatment the outcome of these disorders, particularly for AN, would have been worse. In addition, the number of participants with AN is relatively small. However, given the frequency of some form of treatment for eating disorders found in this and other studies (6) it is unlikely that a prospective study would be able to follow an untreated cohort over time. Finally, the EDNOS group was composed of partial cases of AN, BN, and BED omitting other syndromes that now populate EDNOS such as night eating syndrome, and purging syndrome (4). However, the majority of EDNOS cases appear to be subclinical variants of the three main ED’s (4).

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that EDNOS is a way-station for those moving from a full ED or from remission to another ED. The retrospective examination of the EDNOS group found that the majority had a full ED diagnosis in the past and that there are few true EDNOS cases. It is likely that the composition of EDNOS will vary with the age of the cohort. For example, in adolescence it may be that a higher proportion of cases would be on the path toward a full ED syndrome.

These results may have implications for DSM-V and for the problematic diagnostic category of EDNOS (2). Given that EDNOS is largely a transient category it may make sense to use that diagnosis only for cases that have never met criteria for a full ED. For example, a patient with AN who transitions to another ED diagnosis including EDNOS should continue to be diagnosed as having AN. This would remove the majority of diagnoses from the EDNOS category to a full ED syndrome leaving only those who have not yet met lifetime criteria for a full ED diagnosis and those with as yet undefined syndromes as EDNOS cases.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported in part by grants from the McKnight Foundation to Cornell University, the University of Minnesota, and Stanford University and by grants P30 DK 50456 and K02 MH 65919.

References

- 1.Fairburn CC, Cooper Z, Bohn K, O’Connor M, Doll HA, Palmer RL. The severity and status of eating disorder NOS: Implications for DSM-V. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1705–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating Disorder NOS (EDNOS): An example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay PJ, JM, Buttner P, Darby A. Eating disorder behaviors are increasing: findings from two sequential community surveys in Australia. PLoS ONE. 2008;6:e1541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockert W, Kaplan AS, Olmsted MP. Eating disorder not otherwise specified: The view from a tertiary care treatment center. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:S99–103. doi: 10.1002/eat.20482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Striegel-Moore RH, Debar L, Wilson GT, Dickerson J, Rosselli F, Petrin N, Lynch M, Kraemer HC. Health services use in eating disorders. Psychol Med. 2007 doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001833. Published online by Cambridge University Press 02 Nov 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Tovim D, Kay W, Gilchrist P, Freeman R, Kalucy R, Esterman A. Outcome in patients with eating disorders: A 5-year study. Lancet. 2001;357:1254–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04406-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Shea MT, Skodol AE, Stout RL, Pagano ME, Yen S, McGlashan TH. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified is not influenced by personality disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:319–330. doi: 10.1002/eat.10196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzog D, DHJ, Burns CD. A follow-up study of 33 subdiagnostic eating disordered women. Int J Eat Disord. 1993;14:261–267. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199311)14:3<261::aid-eat2260140304>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grilo CM, Pagano ME, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, McGlashan TH, Gunderson JG, Stout RL. Natural course of bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified: 5-year prospective study of remissions, relapses, and the effects of personality disorder psychopathology. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:738–746. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Hedlund S. Long-term course of binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa: Relevance for nosology and diagnostic criteria. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:577–586. doi: 10.1002/eat.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lilenfeld LR, Ringham R, Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD. A family history study of binge eating disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:247–54. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pope HG, Lalonde JK, Pindyck LJ, Walsh BT, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge eating disorder: A stable syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2181–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Berry JM, Pindyck LJ, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge eating as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:313–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Hill L, le Grange D, Powers P, et al. Latent profile analysis of a cohort of patients with eating disorder not otherwise specified. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40 (Suppl):S 104–106. doi: 10.1002/eat.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crow SJ, Agras WS, Halmi K, Mitchell JE, Kraemer HC. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: a multicenter study. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32(3):309–18. doi: 10.1002/eat.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper Z, Cooper PJ, Fairburn CG. The validity of the eating disorder examination and its subscales. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:807–12. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.6.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B. The Life: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders:Patient Edition (SCID-I/P Version 2.0) New York: Biometrics Research Dept., New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Bulik CM. Outcomes of eating disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:293–309. doi: 10.1002/eat.20369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman P, O’Connor M. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in young women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(7):659–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog DB, Dorer DJ, Keel PK, Selwyn SE, Sherrie E, Ekeblad ER, Flores AT, Greenwood DN, Burwell RA, Keller MB. Recovery and relapse in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:829–837. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]